Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified several loci associated with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) risk. Pathway analysis complements conventional GWAS analysis. We applied the recently developed linear combination test for pathways to datasets drawn from independent PBC GWAS in Italian and Canadian subjects. Of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes and BioCarta pathways tested, 25 pathways in the Italian dataset (449 cases, 940 controls) and 26 pathways in the Canadian dataset (530 cases, 398 controls) were associated with PBC susceptibility (P < 0.05). After correcting for multiple comparisons, only the eight most significant pathways in the Italian dataset had FDR < 0.25 with tumor necrosis factor/stress-related signaling emerging as the top pathway (P = 7.38 × 10−4, FDR = 0.18). Two pathways, phosphatidylinositol signaling and hedgehog signaling, were replicated in both datasets (P < 0.05), and subjected to two additional complementary pathway tests. Both pathway signals remained significant in the Italian dataset on modified gene set enrichment analysis (P < 0.05). In both GWAS, variants nominally associated with PBC were significantly overrepresented in the phosphatidylinositol pathway (Fisher exact P < 0.05). These results point to established and novel pathway-level associations with inherited predisposition to PBC that on further independent replication and functional validation, may provide fresh insights into PBC etiology.

Keywords: linear combination test, phosphatidylinositol signaling, hedgehog signaling, autoimmune disease

INTRODUCTION

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is the most common autoimmune liver disease and primarily affects women, with a prevalence of 1 in 1000 over the age of 40 years.1 The serological hallmark of PBC is the formation of anti-mitochondrial antibodies against the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex subunit E2 (PDC-E2).2 The antibodies specifically recognize immunoreactive PDC-E2 within apoptotic blebs of biliary epithelial cells.3 Untreated disease involves progressive, non-suppurative granulomatous inflammation and autoreactive T lymphocyte-mediated destruction of the small-to-medium intrahepatic bile ducts leading to chronic cholestasis, portal inflammation, cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease.4 The accepted concept of PBC etiology is that it arises on a background of strong genetic susceptibility that is reactive to a variety of potential environmental triggers. The disease has a monozygotic concordance of 63%,5 a sibling relative risk of 10.5,6 and 1–6% of all patients with PBC have at least one first-degree relative affected.7 Other autoimmune disorders also tend to be more common in the families of PBC cases.8 To date, there have been three genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for PBC that have reproducibly identified several risk loci that implicate key gene loci involved in adaptive immunity and inflammatory response.9–12

The genetic associations with PBC risk identified by the genome-wide approach are just those single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that met the most stringent criterion for statistical significance applied to account for the exceedingly large number of statistical comparisons made in a GWAS. Many more variants are typically associated with disease only at the nominal significance level in a GWAS and are therefore not investigated further.13 However, if the excess familial risk for PBC is to be explained, some of these discarded variants must be false negatives and constitute genuine PBC susceptibility loci. Moreover, due to population genetic heterogeneity, different SNPs in or near the same gene or in a functionally related gene may be associated with the disease among individual cases in a GWAS sample. This makes it less likely that a replicable association with the disease would be found when testing SNPs one at a time as is usually done in a GWAS.14 Single nucleotide polymorphisms and the genes that they belong to are not random entities. The products of specific sets of genes interact as members of discrete molecular and cellular pathways with defined biological function.15 Collectively, these observations have motivated the development of methods for the secondary or complementary statistical analysis of GWAS data that use biological pathways represented by gene sets, instead of SNPs, as the units of analysis.16 Pathway-based tests provide a dynamic biologically plausible template to efficiently integrate statistical information from the multitude of SNPs with weaker effects that are otherwise missed by conventional single-SNP GWAS analysis.17

In GWAS pathway analysis, one can map SNPs to genes and test for overrepresentation of statistically significant association signals among genes within a known biological pathway compared with the number of such signals among genes outside the pathway. This is termed the ‘competitive’ approach.16 Alternatively, one can jointly test all genes within the pathway for an association with the disease. As the latter only considers disease association signals within a pathway and does not compare them to signals outside the pathway, it is termed the ‘self-contained’ approach. So far, these methods have been successfully employed to analyze GWAS of a diverse group of diseases.18,19 Here, we report the results of pathway analysis of two datasets from previously completed GWAS in independent Italian and Canadian PBC cohorts. We applied a recently developed ‘self-contained’ GWAS pathway analysis method, the linear combination test (LCT) of Luo et at.,20 to identify pathways associated with genetic predisposition to PBC and provide greater insight into the etiology of this complex autoimmune disease. In accordance with recommendations for validating GWAS pathway analysis findings by complementary methods,14,21 the statistical significance of top pathways that were replicated in both datasets was further confirmed by using two ‘competitive’ pathway-oriented strategies.

RESULTS

Linear combination test for pathway analysis

First, we individually analyzed the Italian and Canadian datasets using the LCT.20 This algorithm uses raw genotype data to first compute genome-wide single-SNP association statistics (see Material and methods for details). After assigning all SNPs between the start site and the 3’ untranslated region to a gene, single-SNP P-values were combined for each gene using the gene-level LCT statistic derived by Luo, et al.20 Genes were classified into pathways using the well-accepted Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and BioCarta resources. Finally, gene-level statistics for all genes within a pathway were combined using the pathway-level LCT (see Material and methods). For these tests, we set P < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.25 as a stringent criteria for significance (Material and methods).

In the Italian dataset, 207 695 SNPs out of 468 982 SNPs were located within genes and mapped to 14 527 genes. Of these, 4172 genes were assigned to pathways for LCT analysis. In the Canadian dataset, 143 059 SNPs out of 334 444 SNPs were located within genes and mapped to 14792 genes. Of these, 4226 genes were assigned to pathways for LCT analysis. Pathways with > 10 genes accounted for 175 BioCarta and 172 KEGG pathways in the Italian study and 176 BioCarta and 172 KEGG pathways in the Canadian study. At the gene-level, the LCT identified 253 genes in the Italian sample and 236 genes in the Canadian sample with P-value < 0.05. These genes are listed in Supplementary Table S1. As shown in Supplementary Table S2, there was limited overlap between significant genes in the two datasets.

Pathways suggested from the linear combination test analyses

At the pathway-level, the LCT identified 25 pathways (13 BioCarta, 12 KEGG) in the Italian dataset at the P < 0.05 level (Table 1). Of these, eight pathways achieved the threshold for statistical significance we set for this study (P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25). Notably, these eight included three pathways that are likely to be important in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune processes: tumor necrosis factor (TNF)/stress-related signaling pathway (P = 7.38 × 10−4, FDR = 0.18), antigen processing and presentation (P = 1.08 × 10−3, FDR = 0.18), and chaperones modulate interferon signaling pathway (P = 2.33 × 10−3 FDR = 0.192).

Table 1.

Pathways identified in the Italian dataset using linear combination test analysisa

| Rank | Pathway name | Source | Pathway size (genes) |

P-value (LCT) |

FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TNF/stress-related signaling pathway | BioCarta | 25 | 0.0007 | 0.180 |

| 2 | Bole of MAL in Rho-mediated activation of SRF pathway | BioCarta | 19 | 0.0009 | 0.180 |

| 3 | Antigen processing and presentation | KEGG | 88 | 0.0011 | 0.180 |

| 4 | Hypoxia and p53 in the cardiovascular system pathway | BioCarta | 23 | 0.0019 | 0.192 |

| 5 | Glycerophospholipid metabolism | KEGG | 66 | 0.0022 | 0.192 |

| 6 | Chaperones modulate interferon signaling pathway | BioCarta | 19 | 0.0023 | 0.192 |

| 7 | Small cell lung cancer | KEGG | 87 | 0.0035 | 0.218 |

| 8 | Acetylation and deacetylation of RelA in the nucleus pathway | BioCarta | 16 | 0.0047 | 0.245 |

| 9 | Signal transduction through IL1R pathway | BioCarta | 33 | 0.0059 | 0.269 |

| 10 | CBL-mediated ligand-induced downregulation of EGF receptors pathway | BioCarta | 13 | 0.0066 | 0.276 |

| 11 | Rho cell motility signaling pathway | BioCarta | 32 | 0.0092 | 0.333 |

| 12 | Role of PI3K subunit p85 in the regulation of actin organization and cell migration pathway | BioCarta | 16 | 0.0120 | 0.377 |

| 13 | Non-small cell lung cancer | KEGG | 54 | 0.0154 | 0.436 |

| 14 | Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | KEGG | 77 | 0.0156 | 0.436 |

| 15 | VEGF signaling pathway | KEGG | 74 | 0.0232 | 0.582 |

| 16 | Calcium signaling pathway | KEGG | 179 | 0.0282 | 0.582 |

| 17 | CD40L signaling pathway | BioCarta | 15 | 0.0300 | 0.582 |

| 18 | Endometrial cancer | KEGG | 52 | 0.0311 | 0582 |

| 19 | Cyclins and cell Cycle regulation pathway | BioCarta | 23 | 0.0313 | 0.582 |

| 20 | MAPK signaling pathway | KEGG | 267 | 0.0335 | 0.582 |

| 21 | Complement and coagulation cascades | KEGG | 69 | 0.0383 | 0.636 |

| 22 | Hedgehog signaling pathway | KEGG | 57 | 0.0438 | 0.636 |

| 23 | Graft-versus-host disease | KEGG | 42 | 0.0460 | 0.636 |

| 24 | Ras-independent pathway in NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity pathway | BioCarta | 20 | 0.0469 | 0.636 |

| 25 | Classical complement pathway | BioCarta | 14 | 0.0484 | 0.639 |

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LCT, linear combination test.

All pathways with P < 0.05 are shown.

There were 26 pathways (8 BioCarta, 18 KEGG) in the Canadian dataset at the P < 0.05 level using LCT analysis (Table 2). None of these pathways met the more stringent criterion for statistical significance (P < 0.05 along with FDR < 0.25). However, three of the pathways had an FDR of < 0.5: regulation and function of carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) in liver pathway (P = 5.68 × 10−4, FDR = 0.285), bone remodeling pathway (P = 2.33 × 10−3, FDR = 0.493) and apoptosis (P = 3.96 × 10−3, FDR = 0.493). For both datasets, there was no significant correlation between the number of genes in a pathway and pathway rank. Complete LCT pathway analysis results for the Italian dataset are presented in Supplementary Table S3 and for the Canadian dataset in Supplementary Table S4. We also present the pathway results from both datasets combined using Fisher’s method for meta-analysis in Supplementary Table S5.

Table 2.

Pathways identified in the Canadian dataset using linear combination test analysisa

| Rank | Pathway name | Source | Pathway size (genes) | P-value (LCT) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regulation and function of ChREBP in liver pathway | BioCarta | 44 | 0.0006 | 0.285 |

| 2 | Bone remodeling pathway | BioCarta | 14 | 0.0023 | 0.493 |

| 3 | Apoptosis | KEGG | 90 | 0.0040 | 0.493 |

| 4 | Renal cell carcinoma | KEGG | 69 | 0.0101 | 0.648 |

| 5 | Phenylalanine metabolism | KEGG | 21 | 0.0102 | 0.648 |

| 6 | Keratan sulfate biosynthesis | KEGG | 16 | 0.0114 | 0.648 |

| 7 | DNA replication | KEGG | 36 | 0.0128 | 0.648 |

| 8 | Tyrosine metabolism | KEGG | 46 | 0.0129 | 0.648 |

| 9 | Stress induction of HSP regulation pathway | BioCarta | 15 | 0.0152 | 0.693 |

| 10 | The IGF-1 receptor and longevity pathway | BioCarta | 15 | 0.0183 | 0.693 |

| 11 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | KEGG | 19 | 0.0204 | 0.693 |

| 12 | Regulation of BAD phosphorylation pathway | BioCarta | 26 | 0.0247 | 0.693 |

| 13 | Basal cell carcinoma | KEGG | 55 | 0.0285 | 0.693 |

| 14 | Role of mitochondria in apoptotic signaling pathway | BioCarta | 21 | 0.0329 | 0.693 |

| 15 | Colorectal cancer | KEGG | 85 | 0.0332 | 0.693 |

| 16 | Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | KEGG | 77 | 0.0335 | 0.693 |

| 17 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | KEGG | 263 | 0.0365 | 0.693 |

| 18 | Wnt signaling pathway | KEGG | 150 | 0.0375 | 0.693 |

| 19 | Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is regulated via AKT/mTOR pathway | BioCarta | 20 | 0.0385 | 0.693 |

| 20 | Hedgehog signaling pathway | KEGG | 57 | 0.0407 | 0.693 |

| 21 | Adherens junction | KEGG | 78 | 0.0434 | 0.693 |

| 22 | IL-10 anti-inflammatory signaling pathway | BioCarta | 17 | 0.0457 | 0.693 |

| 23 | Carbon fixation | KEGG | 24 | 0.0460 | 0.693 |

| 24 | Bladder cancer | KEGG | 42 | 0.0460 | 0.693 |

| 25 | Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | KEGG | 135 | 0.0476 | 0.693 |

| 26 | Biosynthesis of phenylpropanoids | KEGG | 33 | 0.0478 | 0.693 |

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; LCT, linear combination test.

All pathways with P < 0.05 are shown.

Two pathways reached the P < 0.05 level in both datasets using the LCT. They were the phosphatidylinositol signaling system (Italian: P = 0.016, FDR = 0.436; Canadian: P = 0.034, FDR = 0.693; meta-analysis P = 4.48 × 10−3) and the hedgehog signaling pathway (Italian: P = 0.044, FDR = 0.636; Canadian: P = 0.041, FDR = 0.693; meta-analysis P = 0.013).

Complementary analyses supports specific pathways

The phosphatidylinositol signaling system and the hedgehog signaling pathways were followed up in each dataset by two complementary pathway analysis methods (Table 3). First, we applied i-GSEA4GWAS, a modification of the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) approach that uses SNP label permutation (see Material and methods).22 Using the i-GSEA4GWAS algorithm, the association between the phosphatidylinositol signaling system pathway and PBC was found to be statistically significant in the Italian dataset (P = 0.003), but not in the Canadian sample. Similarly, the hedgehog signaling pathway yielded significant results on i-GSEA4GWAS in the Italian dataset only (P = 0.005).

Table 3.

Complementary tests for pathways identified at the P < 0.05 level in both datasets using LCT

| Pathway namea | LCT |

GSEAb |

Fisher’s exact test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italian P-value (FDR) |

Canadian P-value (FDR) |

Italian P-value |

Canadian P-value |

Italian P-value (Ratioc) |

Canadian P-value (Ratioc) |

|

| Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | 0.0156 | 0.0335 | 0.003 | NS | 1.4E-04 | 0.0003 |

| (0.436) | (0.693) | (0.416) | (0338) | |||

| Hedgehog signaling pathway | 0.0438 | 0.0407 | 0.005 | NS | 0.103 | 1.000 |

| (0.636) | (0.693) | (0.281) | (0.158) | |||

Abbreviations: FDR, false discovery rate; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; LCT, linear combination test; NS, not significant.

These pathways were defined in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG).

This analysis was performed using the i-GSEA4GWAS modification of GSEA.

Ratio of number of genes containing at least one SNP with P < 0.05 to the total number of genes in the pathway.

Second, we used Fisher’s exact test as a measure of significance for the proportion of the total genes in each pathway that contained at least one SNP with P-value < 0.05 (see Material and methods for details). Applying Fisher’s exact test, pathway enrichment ratios for the phosphatidylinositol signaling system were significant in both cohorts (Italian: P = 1.42 × 10−5; Canadian: P = 3.45 × 10−4) with 32 out of 77 genes and 26 out of 77 genes from this pathway containing at least one SNP with P < 0.05 in the Italian and Canadian GWAS, respectively. Although hedgehog signaling also demonstrated enrichment in both datasets, ratios for this pathway were not statistically significant (Table 3).

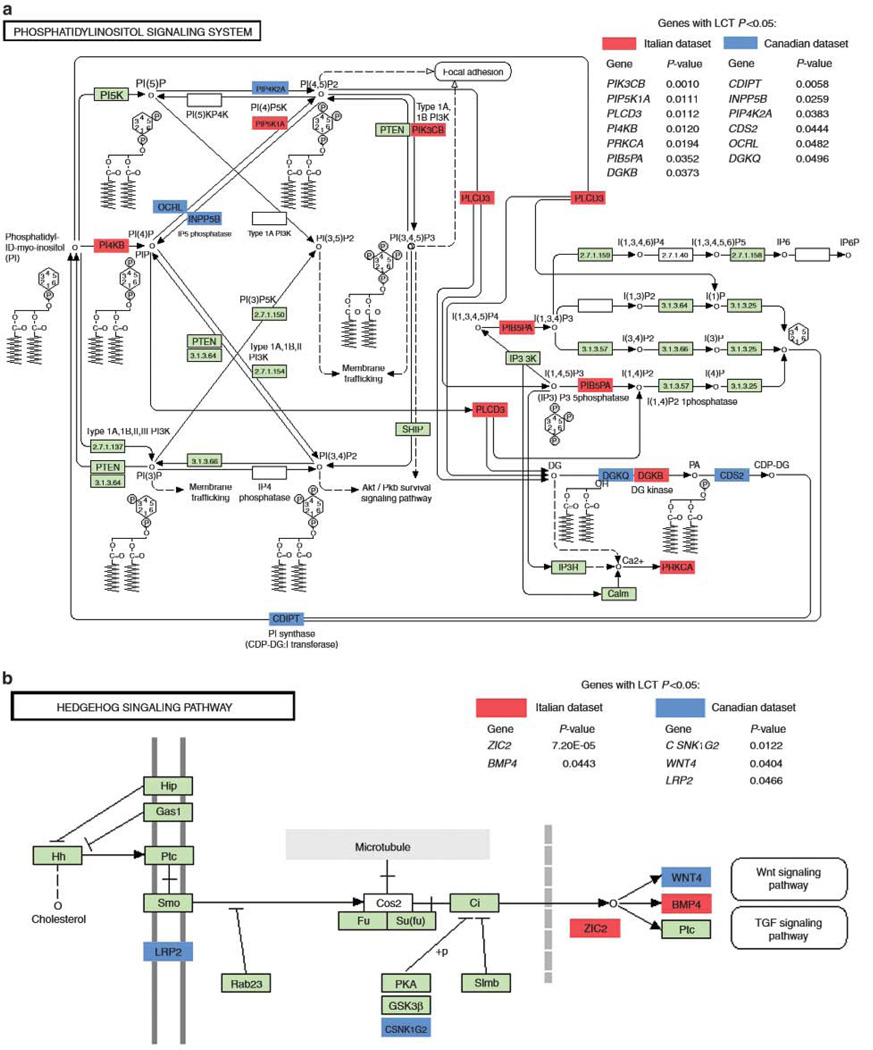

To further dissect the LCT pathway analysis association signal for these two pathways in each dataset we examined the most significant genes underlying the signals (Figure 1). The genes most strongly driving the association for each replicated pathway differed between the two datasets pointing to the genetic heterogeneity and complexity of the disease under study and power limitations in the dataset sample numbers, especially for ascertaining genes with smaller effect size.

Figure 1.

Genes identified in the phosphatidylinositol and hedgehog signaling pathways. Genes reaching statistical significance for the phosphatidylinositol signaling system (panel a) and the hedgehog pathway (panel b) are shown by color highlights (red, Italian dataset; blue, Canadian dataset)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a newly developed pathway-based method, the LCT, to analyze two datasets obtained from previously completed GWAS of Italian and Canadian PBC cohorts. At the conservative cutoff for statistical significance (P < 0.05 and FDR < 0.25) that we adopted, the LCT identified eight pathways associated with the risk of development of PBC in the Italian dataset. We leveraged the availability of data from the two independent, geographically separated PBC case populations to evaluate our findings more broadly. In the interpretation of our results, we focus on those pathways that showed nominal evidence of association in both the Italian and in the Canadian dataset, and emphasize that GWAS pathway analysis is primarily a tool to generate hypothesis for further testing. Two KEGG pathways, phosphatidylinositol signaling and hedgehog signaling systems, attained the P < 0.05 level of significance on LCT pathway analysis in both datasets but did not meet the FDR < 0.25 criterion in either dataset. Both pathways were significant in the larger (Italian) dataset by a modified GSEA, further suggesting their involvement in PBC genetic susceptibility. Simple pathway enrichment ratios for phosphatidylinositol signaling also remained statistically significant in both datasets using Fisher’s exact test-Current experimental evidence offers a variety of putative mechanisms that may underpin the possible role of phosphatidylinositol and hedgehog signaling activity in PBC etiology. Each of these mechanisms serves as a potential avenue that requires follow-up functional investigation.

The phosphatidylinositol signaling system pathway is an integral component of the adaptive immune response and is essential for the maintenance of self-tolerance.23 Phosphatidylinositol signaling is known to be a key controller of T helper 17 cell differentiation.24–25 T helper 17 cells, a subset of helper T cells that produce interleukin 17, are major drivers of both inflammation and autoimmunity.26 T helper 17 differentiation may be modulated by dendritic cell interleukin 12 (IL-12) through its effect on interferon-γ.27 It has been demonstrated that dendritic cell IL-12 production is in turn positively regulated by the p110 β catalytic subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K).28 Interestingly, the PIK3CB gene coding for the PI3K p110β isoform, emerged as the most significant gene of the phosphatidylinositol pathway in the Italian data (P = 9.54 × 10−4, Figure 1a). The importance of IL-12 to PBC pathogenesis is highlighted by the identification of a strong and reproducible association between the IL12A and ILD2RB2 loci and disease risk in every PBC GWAS conducted thus far.9–2 Further, aberrant signal transduction via the phosphatidylinositol system in PBC is consistent with the role of this pathway in disorders that share genetic susceptibility factors with PBC, especially rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus,29,30

Several pathways biologically related to phosphatidylinositol signaling were also uncovered using the LCT analysis at the P < 0.05 level in our data. A possible non-biological explanation for this observation is that genes common to these different pathways underlie the statistical association. However, pathway overlap cannot account entirely for this observation and there are well-established functional connections between the pathways discovered and events upstream and downstream of the phosphatidylinositol signaling system. One particularly note-worthy relationship involves TNF/stress-related signaling, the top pathway in the Italian dataset. This finding corroborates the independent discovery of seven distinct loci harboring genes related to TNF signaling and downstream Nuclear Factor-KappaB (NF-κB) signaling at the genome-wide significance level in the most recent GWAS of PBC.12 Interactions between specific members of the TNF pathway lead to the induction of apoptosis as well as the activation of NF-κB signaling, which is anti-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory.31 Disturbances in this balance between cell death and survival are now recognized as being critical to PBC progression.32 Possible involvement of the phosphatidylinositol pathway in PBC thus appears to fit well with the TNF hypothesis as this signaling system has been shown to mediate the effects of TNF-α on NF-κB activation,33,34

The hedgehog signaling pathway consists of a family of molecules that control cell-type specification during normal development and are intimately involved in tissue and organ morphogenesis.35 Biliary epithelial cells are the first targets of autoimmune injury in PBC. Increased expression in biliary epithelial cells of hedgehog pathway genes and genes targeted by this pathway has previously been reported in a study of PBC patients.36 Animal models of chronic cholestatic biliary injury also demonstrate activation of hedgehog signaling37 and hedgehog signaling has been linked to the promotion of cholangiocyte chemokine production that may mediate recruitment of inflammatory cells in PBC.38 Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the hepatic fibrosis seen in the natural history of PBC can be partly attributed to epithelial-mesenchymal transition, or to the progressive replacement of biliary epithelial cells by cells of fibroblastic lineage.39 Hedgehog signaling is among the best-known effectors of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.40 Another inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, the Wnt signaling pathway (KEGG), ranked 17th among the pathways in the Canadian sample (P = 0.037, FDR = 0.693).41 Crucially, our analysis of the Italian cohort revealed that the ZIC2 gene, which is pivotal to the cross-talk between hedgehog and Wnt, was the most significant gene not only in the hedgehog pathway, but also for the dataset overall (P = 7.20 × 10−5, Supplementary Table S1).42 The association between Wnt signaling and PBC remains to be elucidated, though the upregulation of genes in this pathway has been reported in an early microarray study of the disorder.43

It is worth noting that the two additional analyses that we used to evaluate the pathways replicated at the P < 0.05 threshold, complement the LCT. Taken together, they test the association between a set of genes and disease predisposition under some of the different underlying genetic architectures that may drive such an association. Although the LCT combines evidence of association from all SNPs that map to a gene, the modified GSEA only accounts for the top SNP signal in each gene and Fisher’s exact test for overrepresentation considers all SNPs in a gene that were nominally significant in the original GWAS.

Our study has several limitations and the results must be interpreted with some caution. The first, and a frequently cited criticism of GWAS pathway analyses in general, was the reliance on canonical pathways that represented < 30% of the total genes mapped in each dataset. However, we sought to reduce the influence of selecting canonical pathways by sourcing our pathways from two standard, manually curated databases containing well-defined pathways. Second, the annotation of protein-coding regions in the human genome is incomplete and moreover, there is substantial non-coding SNP information in intergenic regions that is now known to have both trans-effects as well as long distance cis-effects on the expression of genes in signaling pathways.44 Using SNPs within or close to a gene to represent the gene overlooks such distant functional and regulatory relationships. Third, pathways in the Canadian dataset failed to breach the FDR level for statistical significance that we set and the FDRs of the pathways replicated in both datasets was relatively high. Possible explanations include an inadequate sample size, the behavior of the LCT statistic or the genuine absence of a stronger pathway-level association signal for the pathways tested. The sample size for the study was limited, but PBC is an uncommon disease and assembling large cohorts is difficult. Lastly, the current study was limited to common SNPs (> 5%) in the populations studied and many uncommon SNPs as well as structural variants may underlie a considerable portion of the susceptibility to this disease.

In conclusion, the linear combination method may be useful as a secondary step to single-marker analysis for mining a combination of known and novel biologically plausible disease-related pathways from GWAS data. Pathways such as TNF signaling, antigen processing and presentation, and apoptosis, each of which is an established contributor to genetic predisposition to PBC, were among the top pathways identified.12 Two pathways, phosphatidylinositol signaling system and hedgehog signaling, were replicated at the nominal level of significance in the available datasets and these findings were backed by a complementary pathway analysis approach in at least one of the datasets. Genetic variation in these two pathways has not been frequently associated with PBC in prior work. The findings need to be validated in other independent PBC GWAS cohorts. If explored in greater depth and confirmed by future experimental studies, these results have the potential to yield new targets that may be of value for preventive intervention and therapeutic development against PBC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations

This study included both an Italian and a Canadian cohort. All PBC cases in both GWAS met the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases diagnostic criteria for PBC.

The Italian dataset consisted of 449 PBC cases and 940 controls of homogenous Italian descent with genotypes for 468 982 SNPs from the GWAS described in detail by Liu et al.11 All retained subjects had homogeneous Italian descent genetically inferred by principal components analysis that applied specific criteria to eliminate outliers and individuals of Sardinian origin from the dataset. The cases had a mean age of 552 years, 90.3% were female, 85.4% were anti-mitochondrial antibodies- positive and 31.7% had liver cirrhosis. Stringent quality control standards were implemented as previously described and all SNPs retained had sample call rates > 95%, minor allele frequency > 0.05 and were in Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium test P > 10−5. Pairs of subjects with cryptic relatedness as defined by an identity-by-state score > 0.1 were removed.

The Canadian sample was from the GWAS described in Hirschfield et al.9 and consisted of 530 PBC cases, 398 controls and 334 444 SNPs. The cases had a mean age of 60.7 years, 93% were female, 95.5% were anti-mitochondrial antibodies- positive and 5.2% had received a liver transplant Study genotyping was done at the University of Toronto using the Illumina HumanHap370 BeadChip. Single nucleotide polymorphisms with minor allele frequency < 0.01 were excluded and cryptically related individuals, who had an identity-by-state score > 0.25, were removed. Other data filtering standards were identical to the Italian GWAS.

Ethics statement

All participants in both primary studies provided written informed consent and were enrolled on protocols approved by a local Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each center.

Linear combination test for pathway analysis

The two datasets were analyzed individually using the LCT described by Luo et al.20 The test was made publicly available as part of a free software package that was used for the present pathway analysis (https://sph.uth.tmc.edu/hgc/faculty/xiong/software-A.html). The LCT provided adequate type I error rates in simulation studies that we conducted. The algorithm used raw genotype data to first compute genome-wide single-SNP association statistics. All SNPs between the start site and the 3′-untranslated region were then assigned to the gene using NCBI dbSNP Build 129 and human Genome Build 36.3. As SNPs within genes are correlated due to linkage disequilibrium, traditional methods for combining independent P-values cannot be used to bring together Single-SNP P-values for all SNPs in the gene. Therefore, to test the association of each gene with the disease, we combined P-values for all SNPs within the gene using the gene-level LCT statistic derived by Luo, et al.:20

where e = [1,1,…,1]T. Z = [Z1,…, Zk]T for a gene with k SNPs (given that Z1 = Φ−1 (1 − P1) where, P1 is the P-value of a statistic with a normal or asymptotic normal distribution), Rg is the correlation matrix of Z and TL follows a standard normal distribution under the null hypothesis.

Genes were mapped to pathways from the BioCarta database (http://www.biocarta.com/genes/index.asp) and from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). The default pathway list included with the LCT software contained 299 BioCarta and 202 KEGG pathways. However, we decided to confine the final analysis to pathways containing > 10 genes to avoid testing pathways that were too small. At this stage, P-values for all genes within a pathway were combined using the pathway-level LCT statistic to test association of each pathway with the disease:

where TL = [TL1,…,TLm]T for a pathway with m genes, Rp is the matrix of correlations between the test statistics for all genes in the pathway and TP is asymptotically distributed as the standard normal distribution under the null hypothesis.

Results of the LCT analysis were adjusted for multiple comparisons using FDR control by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.45 Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and q-value or FDR < 0.25, a frequently adopted criterion in GWAS pathway studies.16 A meta-analysis of LCT pathway resulting from both datasets was also conducted using Fisher’s combined probability test.

Additional analyses for replicated pathways

To further validate pathways that were replicated at the nominal significance level (LCT pathway P < 0.05) in both datasets, we conducted additional GWAS pathway analyses on each dataset focused only on the replicated pathways using two complementary strategies.

First, we used the i-GSEA4GWAS adaptation of the classical GSEA genome-wide pathway association method.22 Classical GSEA, as in Wang et al.,45 uses the single-SNP association test statistic for the most significant SNP in each gene to represent the gene. All genes are ranked in descending order of their test statistic value. A weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistic is calculated to determine, within a particular pathway, overrepresentation of highly ranked genes from the ranked list of all genes. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like statistic is normalized to account for differences in the number of genes across pathways. After this point, i-GSEA4GWAS differs from classical GSEA in that it multiplies the normalized statistic by a correction factor. This factor depends on the proportion of significant genes in a pathway and attenuates the possibility of pathways being unduly influenced by a few genes that are very highly ranked. Finally, statistical significance for pathways is calculated after phenotype label permutation in classical GSEA and SNP label permutation in i-GSEA4GWAS. Single nucleotide polymorphisms are permuted across pathways and the method provides a computationally efficient approach to follow-up results from a more comprehensive primary pathway analysis. For i-GSEA4GWAS, we (a) used single-SNP χ2 GWAS analysis results from PLINK (version 1.05) for each dataset,47 (b) tested only those pathways that replicated on LCT in both datasets, (c) used pathway definitions identical to LCT, (d) used the same rules for mapping SNPs to genes as in LCT and (e) performed 1000 SNP label permutations.

The second complementary pathway analysis strategy for validation involved determining the statistical significance of pathway enrichment ratios using Fisher’s exact test. For each dataset, all genes containing at least one SNP with P-value < 0.05 in single-SNP χ2 GWAS analysis were listed. Enrichment ratio for a pathway was calculated as the number of genes in this list that map to the pathway divided by the number of genes in the pathway. As before, only pathways that replicated on LCT in both datasets were tested using pathway definitions identical to LCT. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the probability that the association between genes in the list and genes in the pathway was explained by chance alone. Data were analyzed through the use of IPA (Ingenuity Systems, www.ingenuity.com).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH R01DK056839, NIH R01DK091823, NIH K08AR055688, Hypergenes (European Network for Genetic-Epidemiological Studies HEALTH-F4-2007-201550), Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP74621), the Ontario Research Fund (RE01-061), the Canadian PBC Society, a Canada Research Chair award and the Sherman Family Chair in Genomic Medicine to KAS. The authors thank C Coltescu, AL Mason, P Milkiewicz, RP Meyers, JA Odin, V Liakina, C Vincent and C Levy who assisted in recruiting cases for the Canadian-based PBC study.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

Piero L Almasio (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, DtBiMIS, University of Palermo, Palermo), Domenico Alvaro (Department of Medico-Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies, Fondazione Eleonora Lorillard Spencer Cenci, University Sapienza of Rome, Rome). Pietro Andreone (Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica, Università di Bologna, Bologna), Angelo Andriulli (IRCCS Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital, San Giovanni Rotondo), Cristina Barlassina (Department of Medicine, Surgery, and Dentistry, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan), Antonio Benedetti (Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona), Francesca Bernuzzi (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), llaria Bianchi (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), MariaConsiglia Bragazzi (Department of Medico-Surgical Sciences and Biotechnologies, Fondazione Eleonora Lorillard Spencer Cenci, University Sapienza of Rome, Rome), Maurizia Brunetto (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Pisana, Pisa), Savino Bruno (Department of Internal Medicine, Ospedale Fatebene Fratelli e Oftalmico, Milan), Lisa Caliari (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), Giovanni Casella (Medical Department, Desio Hospital, Desio), Barbara Coco (Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Pisana, Pisa), Agostino Colli (Department of Internal Medicine, AO Provincia di Lecco, Lecco), Massimo Colombo (Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan), Silvia Colombo (Treviglio Hospital, Treviglio), Carmela Cursaro (Dipartimento di Medicina Clinica, Università di Bologna, Bologna), Lory Saveria Croce (University of Trieste, and Fondazione Italiana Fegato (FIF), Trieste), Andrea Crosignani (San Paolo Hospital Medical School, Università di Milano, Milan), Francesca Donate (Fondazione IRCCS Ca′ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan), Gianfranco Elia (Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma, Parma) Luca Fabris (University of Padova, Padova), Annarosa Floreani (Department of Surgical, Oncological and Gastroenterological Sciences, University of Padova, Padova), Andrea Galli (University of Florence, Florence), Ignazio Grattagliano (Italian College of General Practicioners, ASL Bari), Roberta Lazzari (Department of Surgical, Oncological and Gastroenterological SciencesUniversity of Padova, Padova), Ana Lleo (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), Fabio Macaluso (Gastroenterology and Hepatology Unit, DiBiMIS, University of Palermo, Palermo), Fabio Marra (University of Florence, Florence), Marco Marzioni (Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona), Elisabetta Mascia (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), Alberto Mattalia (Santa Croce Carle Hospital, Cuneo), Renzo Montanari (Ospedale di Negrar, Verona), Lorenzo Morini (Magenta Hospital, Magenta), Filomena Morisco (University of Naples, Federico II, Naples), Luigi Muratori (Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna), Paolo Muratori (Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna), Grazia Niro (IRCCS Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza Hospital, San Giovanni Rotondo), Antonio Picciotto (University of Genoa, Genoa), Mauro Podda (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano) Piero Portincasa (Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, University Medical School, Bari), Daniele Prati (Ospedale Alessandro Manzoni, Lecco, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan), Chiara Raggi (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), Floriano Rosina (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Center for Predictive Medicine, Gradenigo Hospital, Turin), Sonia Rossi (Department of Internal Medicine, Ospedale Fatebene Fratelli e Oftalmico, Milan), Ilaria Sogno (Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Rozzano), Giancarlo Spinzi (Azienda Ospedaliera Valduce, Como), Mario Strazzabosco (Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511, USA and University of Milan-Bicocca, Monza), Sonia Tarallo (Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Center for Predictive Medicine, Gradenigo Hospital, Turin), Mirko Tarocchi (University of Florence, Florence), Claudio Tiribelli (University of Trieste, and Fondazione Italiana Fegato (FIF), Trieste), Pierluigi Toniutto (University of Udine, Udine), Maria Vinci (Ospedale Niguarda, Milan), Massimo Zuin (San Paolo Hospital Medical School, Università di Milano, Milan).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Genes and Immunity website (http://www.natue.com/gene)

REFERENCES

- 1.Invernizzi P, Selmi C, Gershwin ME. Update on primary biliary cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Invernizzi P, Lleo A, Podda M. Interpreting serological tests in diagnosing autoimmune liver diseases. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:161–172. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lleo A, Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Podda M, Coppel RL, Mackay IR, et al. Apotopes and the biliary specificity of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;49:871–879. doi: 10.1002/hep.22736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:291–308. doi: 10.1002/hep.22906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selmi C, Mayo MJ, Bach N, Ishibashi H, Invernizzi P, Gish RG, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins: genetics, epigenetics, and environment. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:485–492. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DE, Watt FE, Metcalf JV, Bassendine MF, James OF. Familial primary biliary cirrhosis reassessed: a geographically-based population study. J Hepatol. 1999;30:402–407. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selmi C, Invernizzi P, Zuin M, Podda M, Seldin MF. Genes Gershwin ME, and (auto)immunity in primary biliary cirrhosis. Genes Immun. 2005;6:543–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gershwin ME, Selmi C, Worman HJ, Gold EB, Watnik M, Utts J, et al. Risk factors and comorbidities in primary biliary cirrhosis: a controlled interview based study of 1032 patients. Hepatology. 2005;42:1194–1202. doi: 10.1002/hep.20907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Xu C, Lu Y, Xie G, Lu Y, et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis associated with HLA, IL12A, and IL12RB2 variants. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2544–2555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschfield GM, Liu X, Han Y, Gorlov IP, Lu Y, Xu C, et al. Variants at IRF5-TNPO3, 17q12-21 and MMEL1 are associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:655–657. doi: 10.1038/ng.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X, Invernizzi P, Lu Y, Kosoy R, Lu Y, Bianchi I, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses identify three loci associated with primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:658–660. doi: 10.1038/ng.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mells GF, Floyd JA, Morley KI, Cordell HJ, Franklin CS, Shin SY, et al. Genome wide association study identifies 12 new susceptibility loci for primary biliary cirrhosis. Nat Genet. 2011;43:329–332. doi: 10.1038/ng.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarthy MI, Abecasis GR, Cardon LR, Goldstein DB, Little J, Ioannidis JP, et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;9:356–369. doi: 10.1038/nrg2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantor RM, Lange K, Sinsheimer JS. Prioritizing GWAS results: a review of statistical methods and recommendations for their application. Am J Hum Genet. 3010;86:6–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schadt EE. Molecular networks as sensors and drivers of common human diseases. Nature. 2009;461:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature08454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. Analysing biological pathways in genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park JH, Wacholder S, Gail MH, Peters U, Jacobs KB, Chanock SJ, et al. Estimation of effect size distribution from genome-wide association studies and implications for future discoveries. Nat Genet. 2010;42:570–575. doi: 10.1038/ng.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones L, Holmans PA, Hamshere ML, Harold D, Moskvina V, Ivanov D, et al. Genetic evidence implicates the immune system and cholesterol metabolism in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menashe I, Figueroa JD, Garcia-Closas M, Chatterjee N, Malats N, Picornell A, et al. Large-scale pathway based analysis of bladder cancer genome wide association data from five studies of European background. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo L, Peng G, Zhu Y, Dong H, Amos CI, Xiong M. Genome-wide gene and pathway analysis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1045–1053. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gui H, Li M, Sham PC, Cherny SS. Comparisons of seven algorithms for pathway analysis using the WTCCC Crohn’s Disease dataset. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:386. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang K, Cui S, Chang S, Zhang L, Wang J. i-GSEA4GWAS: a web server for identification of pathways/gene sets associated with traits by applying an improved gene set enrichment analysis to genome-wide association study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W90–W95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koyasu S. The role of PI3K in immune cells. Not Immunol. 2003;4:313–319. doi: 10.1038/ni0403-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haylock-Jacobs S, Comerford I, Bunting M, Kara E, Townley S, Klingler-Hoffmann M, et al. PI3Kdelta drives the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting effector T cell apoptosis and promoting Th17 differentiation. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarasenko T, Kole HK, Chi AW, Mentink-Kane MM, Wynn TA, Bolland S. T cell-Specific deletion of the inositol phosphatase SHIP reveals its role in regulating Th1/Th2 and cytotoxic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704853104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschfield GM, Siminovitch KA. Toward the molecular dissection of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1347–1350. doi: 10.1002/hep.23252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goriely S, Cavoy R, Goldman M. Interleukin-12 family members and type I interferons in Th17-mediated inflammatory disorders. Allergy. 2009;64:702–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utsugi M, Dobashi K, Ono A, Ishizuka T, Matsuzaki S, Hisada T, et al. PI3K p110beta positively regulates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12 production in human macrophages and dendritic cells and JNK1 plays a novel role. J Immunol. 2009;182:5225–5231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rommel C, Camps M, Ji H. PI3K delta and PI3K gamma: partners in crime in inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis and beyond? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:191–201. doi: 10.1038/nri2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suarez-Fueyo A, Barber DF, Martinez-Ara J, Zea-Mendoza AC, Carrera AC. Enhanced phosphoinositide 3-kinase delta activity is a frequent event in systemic lupus erythematosus that confers resistance to activation-induced T cell death. J Immunol. 2011;187:2376–2385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Locksley RM, Killeen N, Lenardo MJ. The TNF and TNF receptor superfamilies; integrating mammalian biology. Cell. 2001;104:487–501. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones DE. Pathogenesis of primary biliary cirrhosis. Cell. 2007;56:1615–1624. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hochdorfer T, Kuhny M, Zorn CN, Hendriks RW, Vanhaesebroeck B, Bohnacker T, et al. Activation of the PI3K pathway increases TLR-induced TNF-alpha and IL-6 but reduces IL-1 beta production in mast cells. Cell Signal. 2011;23:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frey RS, Gao X, Javaid K, Siddiqui SS, Rahman A, Malik AB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma signaling through protein kinase Czeta induces NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidant generation and NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16128–16138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lum L, Beachy PA. The Hedgehog response network: sensors, switches, and routers. Science. 2004;304:1755–1759. doi: 10.1126/science.1098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung Y, McCall SJ, Li YX, Diehl AM. Bile ductules and stromal cells express hedgehog ligands and/or hedgehog target genes in primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1091–1096. doi: 10.1002/hep.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omenetti A, Popov Y, Jung Y, Choi SS, Witek RP, Yang L, et al. The hedgehog pathway regulates remodelling responses to biliary obstruction in rats. Gut. 2008;57:1275–1282. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.148619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Omenetti A, Syn WK, Jung Y, Francis H, Porrello A, Witek RP, et al. Repair-related activation of hedgehog signaling promotes cholangiocyte chemokine production. Hepatology. 2009;50:518–527. doi: 10.1002/hep.23019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson H, Kirby JA, Yip WW, Jones DE, Burt AD. Biliary epithelial mesenchymal transition in posttransplantation recurrence of primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:977–981. doi: 10.1002/hep.21624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omenetti A, Porrello A, Jung Y, Yang L, Popov Y, Choi SS, et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates epithelial mesenchymal transition during biliary fibrosis in rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3331–3342. doi: 10.1172/JCI35875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard S, Deroo T, Fujita Y, Itasaki N. A positive role of cadherin in Wnt/beta-catenin signalling during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pourebrahim R, Houtmeyers R, Ghogomu S, Janssens S, Thelie A, Tran HT, et al. Transcription factor Zic2 inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37732–37740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shackel NA, McGuinness PH, Abbott CA, Gorrell MD, McCaughan GW. Identification of novel molecules and pathogenic pathways in primary biliary cirrhosis: cDNA array analysis of intrahepatic differential gene expression. Gut. 2001;49:565–576. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ENCODE Project Consortium. Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis CA, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1278–1283. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.