Abstract

In earlier work, we presented a foundation for the second law of classical thermodynamics in terms of the entropy principle. More precisely, we provided an empirically accessible axiomatic derivation of an entropy function defined on all equilibrium states of all systems that has the appropriate additivity and scaling properties, and whose increase is a necessary and sufficient condition for an adiabatic process between two states to be possible. Here, after a brief review of this approach, we address the question of defining entropy for non-equilibrium states. Our conclusion is that it is generally not possible to find a unique entropy that has all relevant physical properties. We do show, however, that one can define two entropy functions, called S− and S+, which, taken together, delimit the range of adiabatic processes that can occur between non-equilibrium states. The concept of comparability of states with respect to adiabatic changes plays an important role in our reasoning.

Keywords: non-equilibrium thermodynamics, entropy, second law of thermodynamics

1. Introduction

It is commonly held that entropy increases with time. While entropy is fairly unambiguously well defined for equilibrium states, a good part of the matter in the universe, if not most of it, is not in an equilibrium state. It does not have a well-defined entropy as one measures it using equilibrium concepts, for example Carnot cycles, but if one does not know precisely what entropy is for non-equilibrium systems, the notion of increase cannot be properly quantified.

Several definitions of entropy for non-equilibrium states have been proposed in the literature. (See [1] for a review of these matters and [2] for a discussion of steady-state thermodynamics.) These definitions do not necessarily fulfil the main requirement of entropy, however, which, according to our view, is that entropy is a state function that allows us to determine precisely which changes are possible, and which are not, under well-defined conditions. Given the magnitude of this challenge, we do not mean to criticize the heroic efforts of many scientists to define non-equilibrium entropy and use it for practical calculations, but we would like to point out here some of the problems connected with defining entropy in non-equilibrium situations.

Our starting point is the basic empirical fact that under ‘adiabatic conditions’ certain changes of the equilibrium states of thermodynamical systems are possible and some are not. The second law of thermodynamics (at least for us) is the assertion that the possible state changes are characterized by the increase (non-decrease) of an (essentially) unique state function, called entropy, which is extensive and additive on subsystems.

The second law is one of the few really fundamental physical laws. It is independent of models and its consequences are far reaching. Hence, it deserves a simple and solid logical foundation! An approach to the foundational issues was developed by us in several papers in 1998–2003 [3–6]. We emphasize that, contrary to possible first impressions, our approach is not abstract but is based, in principle, on experimentally determined facts. We also emphasize that our approach is independent of concepts from statistical mechanics and model making. This point of view has recently been taken up and even applied to engineering thermodynamics in the textbook by Thess [7].

We can summarize the contents of this paper as follows. We begin, in §2, with a very brief review of our approach to the meaning and existence of entropy for equilibrium systems. An important concept is the adiabatic comparability (comparability for short) of states with respect to the basic relation of adiabatic accessibility (to be explained in the next section). This property, which is usually taken for granted in traditional approaches, often without saying so, means that for any two states X and Y of the same chemical composition there exists an adiabatic process that either takes X to Y or the other way around. If one assumes this a priori, then the existence and uniqueness of entropy follows in our approach quickly from some very simple and physically plausible axioms. However, it is argued in [3–6] that this comparability is, in fact, a highly non-trivial property that needs justification. The mathematically most sophisticated part of this earlier work, and its analytical backbone, is the establishment of comparability starting from some simpler physical assumptions that include convex combinations of states, continuity property of generalized pressure and assumptions about thermal contact.

In §2, we discuss the possibilities for extending the definition of entropy to non-equilibrium states. The concept of comparability will again play an important role. In fact, we shall argue that it may not be possible in general to define one unique entropy for non-equilibrium states that fulfils all the roles of entropy for equilibrium states. Instead, one has to expect a whole range of entropies lying between two extremes, which we call S− and S+. Only when comparability holds do these two state functions coincide, and we have a unique entropy. Comparability for non-equilibrium states, however, is an even less trivial property than for equilibrium states and can certainly not be expected in general.

Another point that comes into play and is far from trivial is reproducibility of states. In fact, it is hard to talk about the properties of states that occur only once in the span of the universe, but that is often the case for non-equilibrium states. For this reason, one must be circumspect about definitions that may look good on paper but cannot be implemented in fact.

2. The entropy of classical equilibrium thermodynamics

This section gives a summary of the main findings by Lieb & Yngvason [3–6]. We consider thermodynamical systems, which can be simple or compound, and have equilibrium states denoted by X,X′, etc. These states are collected in state spaces Γ,Γ′, etc. The composition (also called ‘product’) (X,X′) of a state X∈Γ and X′∈Γ′, which means simply considering the two states jointly but without a physical interaction between them, is just a point in the cartesian product Γ×Γ′. There is also the concept of a scaled copy λX∈λΓ of a state X∈Γ with a real number λ>0. This means that extensive properties like energy, volume, etc. are scaled by λ while intensive properties like pressure, temperature, etc. are not changed. Composition and scaling are supposed to satisfy some obvious algebraic rules.

To begin with, state spaces are just sets, and no more structure is needed for the ‘elementary’ part of our approach. However, for the further development and in particular the derivation of adiabatic comparability, we assume that the state spaces are open convex subsets of  for some N≥2 (depending on the state space). Simple systems, which are the building blocks for composite systems, have a distinguished coordinate, the energy U, and N−1 work coordinates, denoted collectively by V . Often, V is just the volume.

for some N≥2 (depending on the state space). Simple systems, which are the building blocks for composite systems, have a distinguished coordinate, the energy U, and N−1 work coordinates, denoted collectively by V . Often, V is just the volume.

A central concept in our approach (as in [8–12]) is the relation of adiabatic accessibility. Its operational definition (inspired by Planck's formulation of the second law; see [13, p. 89]) is as follows:

A state Y is adiabatically accessible from a state X, in symbols X≺Y (read: ‘X precedes Y ’), if it is possible to change the state from X to Y in such a way that the final effect on the surroundings is that a weight may have risen or fallen.1

It is important to note that the process taking X to Y need not be ‘quasi-static’; in fact, it can be arbitrarily violent.

The following definitions and notations will be applied: if X≺Y or Y ≺X, we say that X and Y are adiabatically comparable (or comparable for short). If X≺Y but Y ⊀X, we write X≺≺Y (read: ‘X strictly precedes Y ’), and if both X≺Y and Y ≺X hold, we write  and say that X and Y are adiabatically equivalent.

and say that X and Y are adiabatically equivalent.

(a). The entropy principle

We can now state the second law (entropy principle):

There is a function called entropy, defined on all states and denoted by S, such that the following holds:

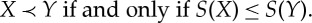

- (1) Characterization of adiabatic accessibility: for two states X and Y with the same ‘matter content’2

2.1 - (2) Additivity and extensivity: for compositions and scaled copies of states, we have

2.2

(i). Remarks

1. The scaling relation in (2.2) says that the entropy doubles when the size of the system is doubled, but this linearity is not a triviality. It need not hold for non-equilibrium entropy, where nonlinear effects might come into play.

The additivity in (2.2) is one of the remarkable facts about entropy (and one of the most difficult to try to prove if there ever is a mathematical proof of the second law from assumptions about dynamics). The states X and X′ can be states of two different systems, yet (2.2) says that the amount by which one system can reduce its entropy in an adiabatic interaction of the two systems is precisely offset by the minimum amount by which the other system is forced to raise its entropy.

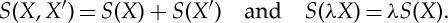

2. It is noteworthy that the mere existence of entropy satisfying the fundamental relation

|

2.3 |

where T=(∂S/∂U)−1 is the absolute temperature, P=T(∂S/∂V) the (generalized) pressure and μi=T(∂S/∂ni) the chemical potentials of the constituents with mole numbers ni in a mixture, leads to surprising connections between quantities that at first sight look unrelated, for instance3

|

2.4 |

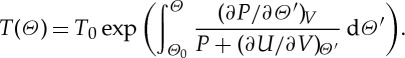

3. Another consequence of the existence of entropy is a formula, owing to Max Planck ([13, pp. 134–135]), that relates an arbitrary empirical temperature scale Θ to the absolute temperature scale T,

|

2.5 |

It is remarkable that the integral on the right-hand side depends only on the temperature although the terms in the integrand depend in general also on the volume, but this follows from the fact that (2.3) is a total differential.

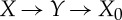

4. The entropy also determines the maximum work that can be obtained from a system in an environment with temperature T0,

| 2.6 |

where X is the initial state with energy U and entropy S, and X0 is the final state with energy U0 and entropy S0. (This quantity is also called availability or exergy.)

The main questions that were addressed in [3–6] are as follows:

Q1 Which properties of the relation ≺ ensure existence and (essential) uniqueness of entropy?

Q2 Can these properties be derived from simple physical premises?

Q3 Which further properties of entropy follow from the premises?

To answer Q1 the following conditions on ≺ were identified in [3–6]:

A1 Reflexivity:

.

.A2 Transitivity: if X≺Y and Y ≺Z, then X≺Z.

A3 Consistency: if X≺X′ and Y ≺Y ′, then (X,Y)≺(X′,Y ′).

A4 Scaling invariance: if λ>0 and X,Y ∈Γ with X≺Y , then λX≺λY .

A5 Splitting and recombination:

.

.A6 Stability: if (X,εZ0)≺(Y,εZ1) for some Z0, Z1 and a sequence of ε's tending to zero, then X≺Y.

These six conditions are all highly plausible if ≺ is interpreted as the relation of adiabatic accessibility in the sense of the operational definition. They are, however, not sufficient to ensure the existence of an entropy that characterizes the relation on compound systems made of scaled copies of Γ. A further property is needed,

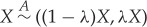

Comparison property (CP) for scaled products of a state space Γ: any two states in (1−λ)Γ×λΓ are adiabatically comparable, for all 0≤λ≤1.

(b). Uniqueness and the basic construction of entropy for equilibrium states

If one assumes CP together with A1–A6, it is a simple matter to prove that the entropy on a state space Γ is uniquely determined, up to an affine change of scale, provided an entropy function exists. The proof goes as follows.

We first pick two reference points X0≺≺X1 in Γ. (Recall that X0≺≺X1 means that X0≺X1, but X1≺X0 does not hold. If there are no such points, then all points in Γ are adiabatically equivalent, and the entropy must be a constant.) Suppose X is an arbitrary state with X0≺X≺X1. (If X≺X0 or X1≺X, we interchange the roles of X and X0 or X1 and X, respectively.) For any entropy function S, we have S(X0)<S(X1) and S(X0)≤S(X)≤S(X1) so there is a unique number λ between 0 and 1 such that

| 2.7 |

By the assumed properties of entropy, this is equivalent to

| 2.8 |

Any other entropy function S′ also leads to (2.8) with λ replaced by some λ′. From the assumptions A1–A6 and X0≺≺X1, it is easy to prove (see [4, lemma 2.2]) that (2.8) can hold for at most one λ, i.e. λ=λ′. Hence, the entropy is uniquely determined, up to the choice of the entropy of X0 and X1, i.e. up to an affine change of scale.

We now come to the existence of entropy. From assumptions A1–A6 and CP, one shows (see [6, equations (8.13)–(8.20)]) that

| 2.9 |

and, denoting this number by λ*,

| 2.10 |

With the choice

| 2.11 |

for some reference points X0≺≺X1, we now have an explicit formula for the entropy:

|

2.12 |

or, equivalently,

|

2.13 |

These formulae use only the relation ≺ and make appeal neither to Carnot cycles nor to statistical mechanics.4

A change of reference points is clearly equivalent to an affine change of scale for S. Thus, the main conclusion so far is

Theorem 2.1 (existence and uniqueness of entropy, given CP) —

The existence and uniqueness (up to a choice of scale) of entropy on Γ is equivalent to assumptions A1–A6 together with the CP.

(i). Remarks

1. The uniqueness is very important. It means that any other definition leading to an entropy function satisfying the requirements of the second law, as stated above, is identical (up to a scale transformation) to the entropy defined by equation (2.12). In order to measure S, it is not necessary to resort to equation (2.12) or (2.13), although it is, in principle, possible to do so. (Note that the use of  and

and  is not a mathematical abstraction but merely reflects the fact that in reality measurements are never perfect.) Instead, one can use any method, like the standard practice when preparing steam tables, namely measuring heat capacities, compressibilities, etc., using equation (2.5) to convert empirical temperatures to absolute temperatures, and then integrating equation (2.3) along an arbitrary path from a reference state to the state whose entropy is to be determined.

is not a mathematical abstraction but merely reflects the fact that in reality measurements are never perfect.) Instead, one can use any method, like the standard practice when preparing steam tables, namely measuring heat capacities, compressibilities, etc., using equation (2.5) to convert empirical temperatures to absolute temperatures, and then integrating equation (2.3) along an arbitrary path from a reference state to the state whose entropy is to be determined.

2. The CP plays a central role in our reasoning, and it is appropriate to make some comments on it. First, we emphasize that, in order to derive (2.10), comparability of all states in (1−λ)Γ×λΓ, and not only of those in Γ, is essential. Previous authors have also noted the importance of comparability. In the seminal work of Giles [9], it appears as the requirement that if X, Y and Z are any states (possibly of composite systems) such that X≺Z and Y ≺Z, then X and Y are comparable. The same conclusion is assumed if Z≺X and Z≺Y . Similar requirements were made earlier by Landsberg [10], Buchdahl [11] and Falk & Jung [12]. These assumptions imply that states fall into equivalence classes such that comparability holds within each class. That comparability is non-trivial, even for equilibrium states, can be seen from the example of systems that have only energy as a coordinate (‘thermometers’) and where only ‘rubbing’ and thermal equilibration are allowed as adiabatic operations. For the composite of two such systems, CP is violated and the entropy is not unique. See [4, fig. 7, p. 65], and also the figure in §3d.

While the above-mentioned references are only concerned with equilibrium states, the authors of [14] require comparability as part of their second law, even for non-equilibrium states. We shall comment further on this issue in §3.

We do not want to adopt CP as an axiom, because we do not find it physically compelling. Our preference is to derive it from some more immediate assumptions. Consequently, an essential part of the analysis in [3–6], and, in fact, mathematically the most complex one, is a derivation of CP from additional assumptions about simple systems, which are the basic building blocks of thermodynamics. At the same time, one makes contact with the traditional concepts of thermodynamics such as pressure and temperature.

As already mentioned, the states of simple systems are described by an energy coordinate U (the first law enters here) and one or more work coordinates, like the volume V . The key assumptions we make are as follows:

— The possibility of forming, by means of an adiabatic process, convex combinations of states of simple systems with respect to the energy U and the work coordinate(s) V .

— The existence of at least one irreversible adiabatic state change, starting from any given state.

— Unique supporting planes for the convex sets

(‘forward sectors’) and a regularity property for their slope (the generalized pressure).

(‘forward sectors’) and a regularity property for their slope (the generalized pressure).

From these assumptions one derives [4, theorems 3.6 and 3.7]

Theorem 2.2 (comparability of states for simple systems) —

Any two states X, Y of a simple system are comparable, i.e. either X≺Y or Y ≺X. Moreover, X∼AY if and only if Y lies on the boundary of

, or, equivalently, X lies on the boundary of

.

This theorem, however, is not enough because to define S by means of the formulae (2.12) and (2.13) we need more, namely comparability for all states in (1−λ)Γ×λΓ, not only in Γ!

The additional concept needed is

— Thermal equilibrium between simple systems, in particular the zeroth law.

In essence, this allows us to make one simple system out of the compound system (1−λ)Γ×λΓ so that the previous analysis can be applied to it, eventually leading to comparability for all states in the compound system. See [4, section 4].

The final outcome of the analysis is (cf. [4, theorems 4.8 and 2.9]):

Theorem 2.3 (entropy for equilibrium states) —

The CP is valid for arbitrary scaled products of simple systems. Hence the relation among states in such state spaces is characterized by an additive and extensive entropy, S.

The entropy is unique up to an overall multiplicative constant and one additive constant for each ‘basic’ simple system.

Moreover, the entropy is a concave function of the energy and work coordinates, and it is nowhere locally constant.

To include mixing processes and chemical reactions as well, the entropy constants for different mixtures of given ingredients, and also of compounds of the chemical elements, have to be chosen in a consistent way. In our approach, it can be proved, without invoking idealized ‘semipermeable membranes’, that the entropy scales of the various substances can be shifted in such a way that X≺Y always implies S(X)≤S(Y). The converse, i.e. that S(X)≤S(Y) implies X≺Y provided X and Y have the same chemical composition, cannot be guaranteed without further assumptions, however. These matters are discussed in [4, section 6].

3. Non-equilibrium states

There exist many variants of non-equilibrium thermodynamics. A concise overview is given in the monograph by Lebon et al. [1], where the following approaches are discussed, among others: classical irreversible thermodynamics (CIT), extended irreversible thermodynamics (EIT), finite-time thermodynamics, theories with internal variables, rational thermodynamics and mesoscopic thermodynamic descriptions. Most of these formalisms focus on states close to equilibrium. Aspects of steady-state thermodynamics are thoroughly discussed in [2].

A further point to note is that the role of entropy in non-equilibrium thermodynamics is considerably less prominent than in equilibrium situations. Equilibrium entropy is a thermodynamic potential when given as a function of its natural variables U and V , i.e. it encodes all equilibrium thermodynamic properties of the system. For a description of non-equilibrium phenomena, on the other hand, more input than the entropy alone is needed.

It is a meaningful question, nevertheless, to ask to what extent an entropy can be defined for non-equilibrium states, preserving as much as possible of the useful properties of equilibrium entropy. To formulate and discuss this question precisely, we consider a system with a space Γ of equilibrium states that is embedded as a subset in some larger space  of non-equilibrium states. We emphasize that

of non-equilibrium states. We emphasize that  need not contain all non-equilibrium states that the system might, in principle, possess, but only a part that is relevant for the problems under consideration. A natural requirement is that states in

need not contain all non-equilibrium states that the system might, in principle, possess, but only a part that is relevant for the problems under consideration. A natural requirement is that states in  are reproducible. It is not clear to us that the entropy of an exploding bomb, for instance, is a meaningful concept (although the energy might be).

are reproducible. It is not clear to us that the entropy of an exploding bomb, for instance, is a meaningful concept (although the energy might be).

Another point to keep in mind is that a non-equilibrium state is, typically, either time dependent or it is not isolated from its environment, as in the case of a non-equilibrium steady state that has to be connected to reservoirs that cause fluxes of heat or electric current to flow through it.

(a). Entropies for non-equilibrium states

We assume that a relation ≺ is defined on  such that its restriction to the equilibrium state space Γ is characterized by an entropy function S, as discussed in §2. The physical meaning of ≺ on

such that its restriction to the equilibrium state space Γ is characterized by an entropy function S, as discussed in §2. The physical meaning of ≺ on  is supposed to be the same as before, i.e. X≺Y means that Y can be reached from X by a process that in the end leaves no traces in the surroundings except that a weight may have been raised or lowered. As discussed in §2, the assumption that the restriction of ≺ to Γ is characterized by an entropy function is equivalent to assuming that this restriction satisfies conditions A1–A6 together with CP. For the non-equilibrium states in

is supposed to be the same as before, i.e. X≺Y means that Y can be reached from X by a process that in the end leaves no traces in the surroundings except that a weight may have been raised or lowered. As discussed in §2, the assumption that the restriction of ≺ to Γ is characterized by an entropy function is equivalent to assuming that this restriction satisfies conditions A1–A6 together with CP. For the non-equilibrium states in  , it is not natural to require A4 (scaling) and A5 (splitting), but we shall assume the following:

, it is not natural to require A4 (scaling) and A5 (splitting), but we shall assume the following:

N1 The relation ≺ on

satisfies our assumptions A1 (reflexivity), A2 (transitivity), A3 (consistency)5 and A6 (stability).

satisfies our assumptions A1 (reflexivity), A2 (transitivity), A3 (consistency)5 and A6 (stability).N2 For every

, there are X′,X′′∈Γ such that X′≺X≺X′′.

, there are X′,X′′∈Γ such that X′≺X≺X′′.

The meaning of the second requirement is that every non-equilibrium state in  can be generated from an equilibrium state in Γ by an adiabatic process, and that every non-equilibrium state can be brought to equilibrium by such a process (e.g. by letting the non-equilibrium state relax spontaneously to equilibrium). We consider this to be very natural, physically.

can be generated from an equilibrium state in Γ by an adiabatic process, and that every non-equilibrium state can be brought to equilibrium by such a process (e.g. by letting the non-equilibrium state relax spontaneously to equilibrium). We consider this to be very natural, physically.

The basic question we now ask is: What can be said about possible extensions of S to functions

on

on

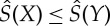

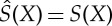

that are monotone with respect to ≺, i.e. that satisfy

that are monotone with respect to ≺, i.e. that satisfy

if X≺Y , and, if X∈Γ, then

if X≺Y , and, if X∈Γ, then

as well?

as well?

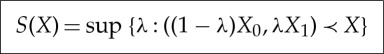

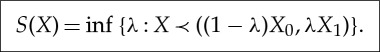

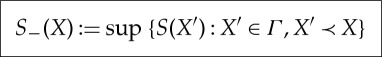

Our answer involves the following two functions:

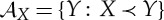

For  define

define

|

3.1 |

and

|

3.2 |

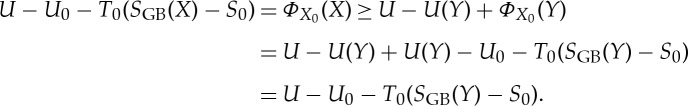

Thus, S− measures how large the entropy can be of an equilibrium state out of which X is created by an adiabatic process, and S+ measures how small the entropy of an equilibrium state can be into which X equilibrates by an adiabatic process.

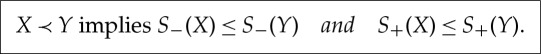

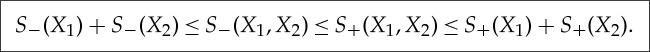

The essential properties of these functions are collected in the following proposition. In words, it says the following: both S− and S+ take only finite values and increase or remain unchanged under adiabatic state changes. A sufficient condition for Y to be adiabatically accessible from X is that S+(X)≤S−(Y). While neither of the functions are necessarily additive, S− is at least superadditive and S+ subadditive (see equation (3.5)). The entropy is unique if and only if S−=S+, because any function that is monotonously increasing or unchanged with respect to the relation of adiabatic accessibility and coincides with S on Γ lies between S− and S+. The unique entropy is then additive, by (3.5).

Proposition 3.1 (properties of S±) —

(a)

for all

.

(b) S±(X)=S(X) for X∈Γ, and S−(X)≤S+(X), for all

.

(c) The

and

in the definition of S± are attained for some X′,X′′∈Γ with X′≺X≺X′′.

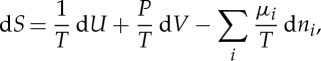

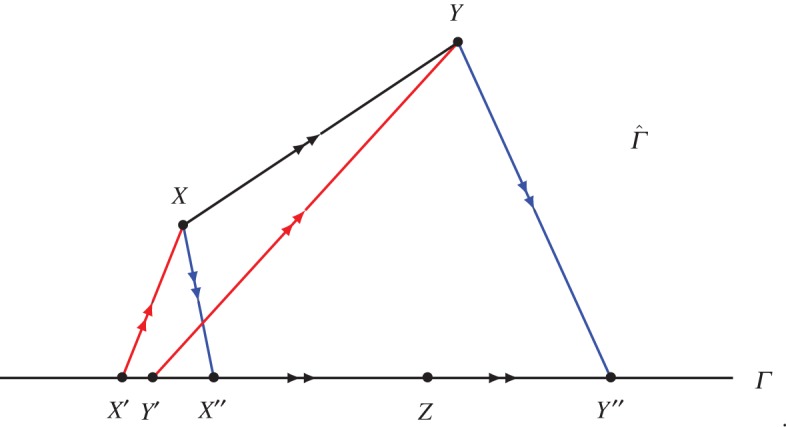

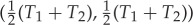

(See figure 1.)

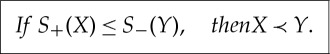

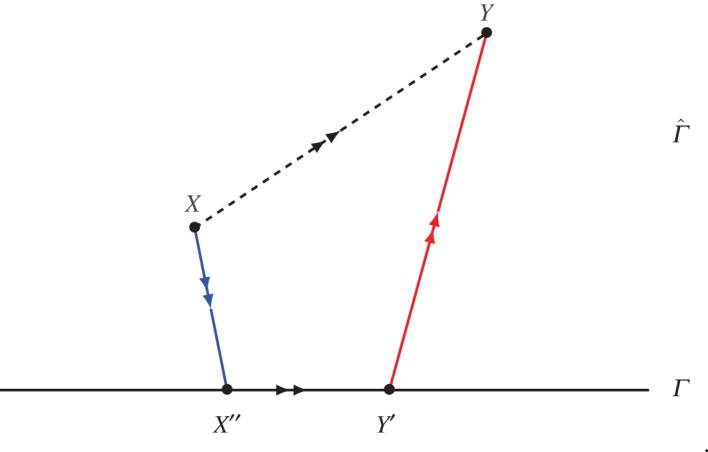

3.3 (See figure 2.)

3.4

3.5 is any function on

that coincides with S on Γ and is such that X≺Y implies

, then

3.6

Figure 1.

This illustrates equation (3.3) with S−(X)=S(X′), S+(X)=S(X′′), S−(Y)=S(Y ′), S+(Y)=S(Y ′′). The arrows indicate adiabatic state changes. The state Z∈Γ with Y ′≺≺Z≺≺Y ′′ is not adiabatically comparable with Y (but it is adiabatically comparable with X because X≺X′′≺Z). (Online version in colour.)

Figure 2.

Illustration of equation (3.4) with S+(X)=S(X′′), S−(Y)=S(Y ′). (Online version in colour.)

Proof. —

(a) and (b) follow immediately from the assumptions on ≺ and the properties of S, namely X′≺X≺X′′ implies S(X′)≤S(X′′).

(c) Since the entropy is concave on Γ and, in particular, continuous, it takes all values between S(X′) and S(X′′) for any two states X′ and X′′ in Γ with X′≺X′′. Hence, by N2 and the definition of S−, there is an X0′∈Γ with S(X′0)=S−(X), and we claim that X0′≺X. Indeed, by the definition of S− there is, for every ε>0, an Xε′∈Γ with Xε′≺X and 0≤S(X′0)−S(Xε′)≤ε. We can pick Z0≺≺Z1∈Γ and 0≤δ(ϵ) such that δ(ε)→0 for ε→0 and S(X′0)+δS(Z0)=S(Xε′)+δS(Z1). Then

Hence, X′0≺X by the stability assumption A6. In the same way, one shows that the infimum defining S+(X) is attained.

(d) If X≺Y and X′≺X, then X′≺Y , so S−(X)≤S−(Y). Likewise, X≺Y and Y ≺Y ′′ implies X≺Y ′′, so also S+(X)≤S+(Y).

(e) If S+(X)≤S−(Y) then there exists X′′ and Y ′ with X≺X′′, Y ′≺Y and X′′≺Y ′. But then X≺Y by transitivity.

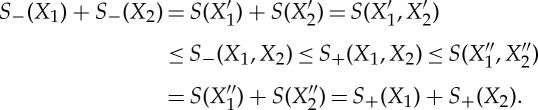

( f ) By (c), there exist Xi′,Xi′′, i=1,2∈Γ such that S−(Xi)=S(Xi′), S+(Xi)=S(Xi′′) and Xi′≺Xi≺Xi′′. From the additivity of the equilibrium entropy S and

we obtain

3.7 (g) Let X′≺X≺X′′ as in (c). Then

3.8 □

The following theorem clarifies the connection between adiabatic comparability and uniqueness of an extension of the equilibrium entropy to the non-equilibrium states. (Recall that two states X and Y are called comparable w.r.t. the relation ≺ if either X≺Y or Y ≺X holds.) Particularly noteworthy is the equivalence of (i), (iii) and (vi) below, which may be summarized as follows: a non-equilibrium entropy, characterizing the relation ≺, exists if and only if every non-equilibrium state is adiabatically equivalent to some equilibrium state.

Theorem 3.2 (comparability and uniqueness of entropy) —

The following are equivalent:

(i) There exists a unique

extending S such that X≺Y implies

.

(ii) S−(X)=S+(X) for all

.

(iii) There exists a (necessarily unique!)

extending S such that

implies X≺Y .

(iv) Every

is comparable with every

, i.e. the CP is valid on

.

(v) Every

is comparable with every Z∈Γ.

(vi) Every

is adiabatically equivalent to some Z∈Γ.

Proof. —

That (i) is equivalent to (ii) follows from (d) and (g) in proposition 3.1. Moreover, (ii) implies (iii) by (e). The implications

are obvious.

(v)→(ii): if X′ and X′′ are as in proposition 3.1(c), and S(X′)=S−(X)<S+(X)=S(X′′), there exists a Z∈Γ with S(X′)<S(Z)<S(X′′). If (v) holds, then either Z≺X or X≺Z. The first possibility contradicts the definition of S− and the latter the definition of S+. Hence S−=S+, so (v) implies (ii).

It is clear that

because CP holds on Γ.

Finally,

: since X′,X′′∈Γ, and S(X′)=S(X′′) (by (ii)), we know that

, because the entropy S characterizes the relation ≺ on Γ by assumption. Now X′≺X≺X′′, so

. □

(b). Maximum work

Assume now that a ‘thermal reservoir’ with temperature T0 is given. Such a reservoir can be regarded as an idealization of a simple system without work coordinates that is so large that an energy change has no appreciable effect on its temperature (defined, as usual, to be the inverse of the derivative of the entropy with respect to the energy). An energy change ΔUres and a corresponding entropy change ΔSres of the reservoir are thus connected by

| 3.9 |

We denote by ΦX0(X) the maximum work that can be extracted from a state  with the aid of the reservoir if the system ends up in a state X0∈Γ with internal energy U0 and entropy S0. If X∈Γ, i.e. X is an equilibrium state, then

with the aid of the reservoir if the system ends up in a state X0∈Γ with internal energy U0 and entropy S0. If X∈Γ, i.e. X is an equilibrium state, then

| 3.10 |

where U is the internal energy of X and S is its entropy. This follows as usual by considering the total entropy change of the system plus reservoir, i.e. S0−S+ΔSres, which has to be ≥0 by the second law for equilibrium states. The work extracted is W=−(ΔUres+U0−U), and using (3.9) we obtain W≤(U−U0)−T0(S−S0). Equality is reached if the process is reversible.

For non-equilibrium states  , the ± entropies defined in (3.1) and (3.2) give at least upper and lower bounds for the maximum work

, the ± entropies defined in (3.1) and (3.2) give at least upper and lower bounds for the maximum work

|

3.11 |

where S± denote the ± entropies of X. This can be seen as follows.

Consider a special process  where the first step is an adiabatic process and where X′′ and X0 are equilibrium states. As, by definition, there is no change to the rest of the universe in the first process other than the motion of a weight, conservation of energy tells us that the work obtained in the step

where the first step is an adiabatic process and where X′′ and X0 are equilibrium states. As, by definition, there is no change to the rest of the universe in the first process other than the motion of a weight, conservation of energy tells us that the work obtained in the step  is U−U′′. In the step

is U−U′′. In the step  , the maximum work (by the standard reasonings for equilibrium states in Γ, see above) is (U′′−U0)−T0(S(X′′)−S0). Altogether

, the maximum work (by the standard reasonings for equilibrium states in Γ, see above) is (U′′−U0)−T0(S(X′′)−S0). Altogether

where we have used that S(X′′)=S+ for X′′ as in proposition 3.1(c). An analogous reasoning applied to  (with X′ as in proposition 3.1(c)) gives

(with X′ as in proposition 3.1(c)) gives

and hence ΦX0(X)≤(U−U0)−T0(S−−S0).

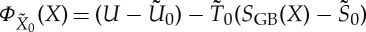

(i). Definition of entropy through maximum work

In their influential textbook on engineering thermodynamics [14], Gyftopolous and Beretta (GB) (see also [15]) take the concept of maximum work as a basis for their definition of entropy. Paraphrasing their definition in our notation, they assume the maximum work ΦX0(X) to be a measurable quantity for arbitrary states X (equilibrium as well as non-equilibrium) and define an entropy SGB(X) through the formula

| 3.12 |

From equation (3.11), it is clear that

| 3.13 |

This follows also from proposition 3.1(g) because

| 3.14 |

which can be seen by considering the process  , obtaining

, obtaining

|

The GB entropy is therefore one possible choice of a function, which is monotone w.r.t. ≺. According to our analysis, it characterizes the relation ≺ if and only if the CP is valid on the whole state space  (as GB assume as part of their second law; see also assumption 2 in [15]), in which case all entropies on

(as GB assume as part of their second law; see also assumption 2 in [15]), in which case all entropies on  extending S coincide. In particular, the GB approach via maximum work leads to the same equilibrium entropy as the approach of §2.

extending S coincide. In particular, the GB approach via maximum work leads to the same equilibrium entropy as the approach of §2.

As we have already stated, however, and shall discuss further below, we consider it implausible to assume adiabatic comparability for general non-equilibrium states. If CP does not hold on  , the entropy SGB may depend in a non-trivial way on the choice of the thermal reservoir and the final state X0.6 This means that the availability for a different final state

, the entropy SGB may depend in a non-trivial way on the choice of the thermal reservoir and the final state X0.6 This means that the availability for a different final state  and different reservoir with temperature

and different reservoir with temperature  is not necessarily given by the formula

is not necessarily given by the formula  if SGB(X) is defined by means of (3.12).

if SGB(X) is defined by means of (3.12).

On the other hand, each of the entropies S±, which are also monotonic w.r.t. ≺ by proposition 3.1(b), is unique up to a scale transformation, because these entropies are defined in terms of the equilibrium entropy on Γ which has this uniqueness property. The inequalities (3.11) hold for all T0 and X0, irrespective of comparability.

(c). Why adiabatic comparability is implausible in general

According to theorem 3.2, the CP on  , and hence the (essential) uniqueness of entropy, is equivalent to the statement that every non-equilibrium state

, and hence the (essential) uniqueness of entropy, is equivalent to the statement that every non-equilibrium state  is adiabatically equivalent to some equilibrium state Z∈Γ. Although there are idealized situations when such comparability can be conceived, it seems to be a highly implausible property in general. The problem can already be expected to arise close to equilibrium as we now discuss.

is adiabatically equivalent to some equilibrium state Z∈Γ. Although there are idealized situations when such comparability can be conceived, it seems to be a highly implausible property in general. The problem can already be expected to arise close to equilibrium as we now discuss.

Consider first the ‘benign’ case where ‘CIT’ (see [1, ch. 2]) can be considered an adequate approximation. The states in  are here described by local values of equilibrium parameters such as temperature, pressure and matter density. In particular, one can define a local entropy density by using the equilibrium equation of state, and, by subsequently integrating this entropy density over the volume of the system, one obtains a global entropy. An equilibrium state in Γ of the same system with the same entropy is, to a good approximation, adiabatically equivalent to the non-equilibrium state. This can be seen by dividing the system into cells such that each cell is approximately in equilibrium and regarding the collection of cells as a composite equilibrium system for which the CP holds by the analysis described in §2.

are here described by local values of equilibrium parameters such as temperature, pressure and matter density. In particular, one can define a local entropy density by using the equilibrium equation of state, and, by subsequently integrating this entropy density over the volume of the system, one obtains a global entropy. An equilibrium state in Γ of the same system with the same entropy is, to a good approximation, adiabatically equivalent to the non-equilibrium state. This can be seen by dividing the system into cells such that each cell is approximately in equilibrium and regarding the collection of cells as a composite equilibrium system for which the CP holds by the analysis described in §2.

The situation changes, however, when CIT is not adequate and the fluxes have to be considered as independent variables, as in ‘EIT’ (cf. [1, ch. 7]). In this situation, also the local temperature has to be replaced by a different variable (cf. [1, section 7.1.2]).7 A phenomenological ‘extended entropy’, depending explicitly on the heat flux, can be considered and even computed in some simple cases. It has the property of increasing monotonously in time when heat conduction is described by Cattaneo's model [16] with a hyperbolic heat transport equation rather than the parabolic Fourier's law.8 The classical entropy, in contrast, may oscillate (see fig. 7.2 in [1]) and does therefore not comply with the second law. Also, the argument above for establishing adiabatic equivalence with equilibrium states no longer applies. Although we do not have a rigorous proof, we consider it highly implausible that a state that is significantly influenced by the flux can be adiabatically equivalent to an equilibrium state, where no flux is present, for this would mean that turning the flux on or off could be done reversibly. Unless this can be done, however, CP does not hold on  and there is no unique entropy.

and there is no unique entropy.

If one moves further away from equilibrium, not even EIT may apply and CP becomes even less plausible. In extreme cases like an exploding bomb, one may even question whether it is meaningful to talk about entropy as a state function at all, because the highly complex situation just after the explosion cannot be described by reproducible macroscopic variables.

For systems with reproducible states, the entropies S± are at least well defined and in principle measurable, although it may not be easy to do so in practice. They provide bounds on the possible adiabatic state changes in the system and the maximum work that can be extracted from the system in a given state and a given environment. The difference

| 3.15 |

which is unique up to a universal multiplicative factor, can also be considered as a measure of the deviation of X from equilibrium.

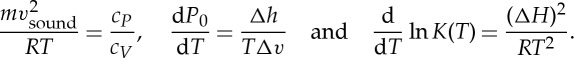

(d). A toy example

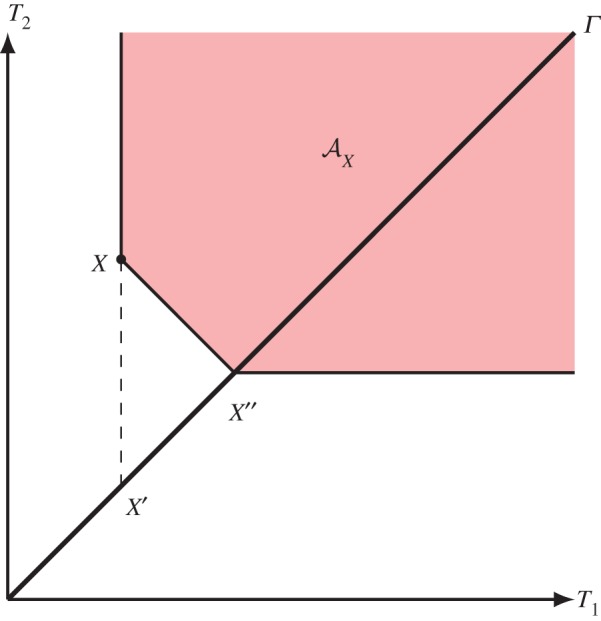

To elucidate the concepts and issues discussed above, we may consider a simple toy example. The system consists of two identical pieces of copper that are glued together by a thin layer of finite heat conductivity. We regard the state of the system as uniquely specified by the energies or, equivalently, the temperatures T1 and T2 of the two copper pieces that are assumed to have constant heat capacity. The layer between them is considered to be so thin that its energy can be ignored. Mathematically, the state space  of this system is thus

of this system is thus  with coordinates (T1,T2) and the equilibrium state space Γ is the diagonal, T1=T2.

with coordinates (T1,T2) and the equilibrium state space Γ is the diagonal, T1=T2.

We assume to begin with that the relation ≺ is defined by the following ‘restricted’ adiabatic operations:

— increasing the energy of each of the copper pieces by rubbing and

— heat conduction between the pieces through the connecting layer obeying Fourier's law.

The forward sector  of X=(T1,T2) then consists of all points that can be obtained by rubbing, starting from any point on the line segment between (T1,T2) and the equilibrium point

of X=(T1,T2) then consists of all points that can be obtained by rubbing, starting from any point on the line segment between (T1,T2) and the equilibrium point  (figure 3).

(figure 3).

Figure 3.

Illustration of  and the points X′ and X′′ in the toy example in §3d. (Online version in colour.)

and the points X′ and X′′ in the toy example in §3d. (Online version in colour.)

As equilibrium entropy, we take  . The points X′ and X′′ of proposition 3.1(c) are

. The points X′ and X′′ of proposition 3.1(c) are

(see figure 3) and accordingly

If we extend the relation ≺ defined above by allowing the copper pieces to be temporarily taken apart and using them as thermal reservoirs between which a Carnot machine can run to equilibrate the temperatures reversibly, then the previous forward sector will be extended and is now characterized by the unique extension of S to

This is precisely the ‘benign’ situation referred to at the beginning of §3c, where CIT applies.

If the parts are unbreakably linked together, however, the situation is different. An irreversible heat flux between the two parts during the adiabatic state change is then unavoidable. If the heat conduction is governed by Cattaneo's rather than Fourier's law, it is necessary to introduce the heat flux as a new independent variable and apply EIT as discussed in the last section. The general objections against the CP and hence the existence of a unique entropy mentioned then apply. But even if we stay with Fourier's law and the two-dimensional state space of the toy model, it is clear that the extended forward sector, obtained by applying Carnot machines in addition to rubbing and equilibration, will depend on the relation between the heat conductivity of the separating layer between the parts, and the heat conductivity between the Carnot machine and the copper pieces. If the latter is finite, a gap between S− and S+ will remain, because equilibration of the temperatures by means of the Carnot machine requires a minimal non-zero time span, during which heat leaks irreversibly through the layer connecting the two pieces.

4. Summary and conclusions

— Under the stated general assumptions A1–A6 for equilibrium states and N1 and N2 for non-equilibrium states, the possibility of defining a single, unique entropy, monotone with respect to the relation of adiabatic accessibility, is equivalent to the adiabatic comparability of states (CP).

— Comparability is a highly non-trivial property. Even in the equilibrium situation, it requires additional axioms beyond A1–A6.

— It is implausible that comparability holds for arbitrary non-equilibrium states. It might, however, be established for restricted classes of non-equilibrium states. In any case, a prerequisite for a useful definition of entropy is that the states can be uniquely identified, and that they are reproducible.

— Further insight into the question of comparability might be obtained from concrete models in which the relation ≺ is defined by some dynamical laws.

Footnotes

Such processes are called work processes in [14].

In the studies by Lieb & Yngvason [3–6], the ‘matter content’ is measured by the scaling parameters of some basic simple systems. Physically, one can think of the amounts of the various chemical ingredients of the system.

The first equation is the relation between the velocity of sound and heat capacities in a dilute gas, and the second is the Clausius–Clapeyron equation with P0(T) the pressure at the coexistence curve between two phases, Δh the specific latent heat and Δv the specific volume change at the phase transition. The last equation is the van 't Hoff relation between the equilibrium constant K(T) of a chemical reaction and the heat of reaction ΔH.

If X1≺≺X, then ((1−λ)X0,λX1)≺X has the meaning λX1≺((λ−1)X0,X) and the entropy is >1. Likewise, the entropy is <0 if X≺≺X0. See [4, remark 2, pp. 27–28].

Compound states have the same meaning as in the equilibrium situation, i.e. we consider two copies of the system and one state of each copy side by side.

The proof of independence in [14,15] uses the assumption that any state can be transformed into an equilibrium state by a reversible work process, which amounts to assuming property (vi) in theorem 3.2.

On the microscopic level, a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution for the velocities of the molecules in a small volume element gets shifted to a different distribution.

Fourier's law is q=−λ∇T, where q is the heat flux, λ the heat conductivity and T the temperature. Cattaneo's law is τ∂q/∂t=−(q+λ∇T), where τ is the time constant of heat flux relaxation.

Funding statement

This work was partially supported by the US National Science Foundation (grant no. PHY 0965859; E.H.L.), the Simons Foundation (grant no. 230207; E.H.L) and the Austrian Science Fund FWF (P-22929-N16; J.Y.). We thank the Erwin Schrödinger Institute of the University of Vienna for its hospitality and support.

References

- 1.Lebon G, Jou D, Casas-Vázquez J. 2008. Understanding non-equilibrium thermodynamics: foundations, applications, frontiers. Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasa Sh-I, Tasaki H. 2006. Steady state thermodynamics. J. Stat. Phys. 125, 125–224 (doi:10.1007/s10955-005-9021-7) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieb EH, Yngvason J. 1998. A guide to entropy and the second law of thermodynamics. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 45, 571–581 (doi:10.1007/978-3-662-10018-9_19) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieb EH, Yngvason J. 1999. The physics and mathematics of the second law of thermodynamics. Phys. Rep. 310, 1–96 [Erratum in Phys. Rep. 1999 314, 669.] (doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(98)00082-9) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieb EH, Yngvason J. 2000. A fresh look at entropy and the second law of thermodynamics. Phys. Today 53, 32–37 [Entropy Revisited, Gorilla and All, Phys. Today 53, Nr. 10, 12–13.] (doi:10.1063/1.883034) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieb EH, Yngvason J. 2003. The entropy of classical thermodynamics. In Entropy (eds Greven A, Keller G, Warnecke G.), pp. 147–193 Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thess A. 2011. The entropy principle: thermodynamics for the unsatisfied. Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carathéodory C. 1909. Untersuchung über die grundlagen der thermodynamik. Math. Annalen 67, 355–386 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles R. 1964. Mathematical foundations of thermodynamics. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landsberg PT. 1956. Foundations of thermodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 28, 363–392 (doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.28.363) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchdahl HA. 1958. A formal treatment of the consequences of the second law of thermodynamics in Carathéodory's formulation. Z. Phys. 152, 425–439 (doi:10.1007/BF01327746) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falk G, Jung H. 1959. Axiomatik der Thermodynamik. In Handbuch der Physik, III/2 (ed. Flügge S.), pp. 119–175 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 13.Planck M. 1945. Treatise on thermodynamics. New York, NY: Dover Publications [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyftopoulos EP, Beretta GP. 2005. Thermodynamics: foundations and applications, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Dover Publications [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beretta GP, Zanchini E. 2011. Rigorous and general definition of thermodynamic entropy. In Thermodynamics (ed. Tadashi M.), pp. 24–50 Rijeka, Croatia: InTech. See http://www.intechopen.com/books/thermodynamics [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cattaneo C. 1945. Sulla conduzione del calore. Atti Seminario Mat. Fis. Univ. Modena 3, 83–101 [Google Scholar]