Abstract

TGFβ is secreted in a latent state and must be “activated” by molecules that facilitate its release from a latent complex and allow binding to high affinity cell surface receptors. Numerous molecules have been implicated as potential mediators of this activation process, but only a limited number of these activators have been demonstrated to play a role in TGFβ mobilization in vivo. Here we review the process of TGFβ secretion and activation using evolutionary data, sequence conservation and structural information to examine the molecular mechanisms by which TGFβ is secreted, sequestered and released. This allows the separation of more ancient TGFβ activators from those factors that emerged more recently, and helps to define a potential hierarchy of activation mechanisms.

Keywords: TGFbeta, activation, evolution, LTBP, Extracellular matrix

1. Introduction to TGFβ

The three TGFβ isoforms encoded by the human genome (TGFβ 1, 2 and 3) are part of a much larger group of 38 human growth factors described as the “TGFβ superfamily”. This group includes growth and differentiation factors (GDFs), bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), and several other important cytokines (1, 2). TGFβ plays a significant role in the development and homeostasis of many tissues. For example it performs crucial roles in wound healing, immunity, muscle differentiation, palate closure, bone growth, and control of cellular proliferation (3–5). However, TGFβ is a beast that can bring devastation to numerous tissues if not properly controlled, and excess TGFβ activity is associated with liver cirrhosis (6), pulmonary fibrosis (7), arthritis (8), muscular dystrophy (9), aortic aneurysm (10), alzheimers disease (11), inflammation (12), and cancer (13, 14), making TGFβ a major target for therapeutic research (15).

The importance of TGFβ in development is clearly demonstrated by the phenotypes of knock out mice (Table 1). TGFβ1 null mice die within three to four weeks of birth due to multiorgan inflammation (3). TGFβ2 null mice display severe disruption in the development of many tissues, yielding congenital heart defects, skeletal defects, cleft palate, and urogenital defects, with most mice dying at birth (4). TGFβ3 null mice die shortly after birth displaying significantly disrupted lung development and cleft palate (16, 17). Redundancy between TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 has been demonstrated by double knock out mice, which display early embryonic death due to failure of midline fusion (5), while Tgfb1RGE/RGE and Tgfb3−/− double mutant mice display cerebral haemorrhages and other defects in vasculogenesis (18).

Table 1.

Mouse knock outs of TGFβ

| Mutation / disruption | Heterozygous mouse phenotype | Homozygous mouse phenotype | Other Notes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ1 |

|

|

|

(3) |

| TGFβ2 |

|

|

|

(4) |

| TGFβ3 |

|

|

|

(16) (17) |

Signalling by TGFβ is regulated at several levels; extracellular factors control TGFβ activation and receptor binding and intracellular factors modulate the downstream signalling pathways. The main features of the TGFβ pathway are summarized in Figure 1. Within the ER, pairs of TGFβ precursor proteins form a dimeric complex, which is subsequently processed into the mature TGFβ dimer and the cleaved latency associated peptide (LAP) dimer by furin cleavage in the trans-Golgi network (19). LAP binds TGFβ with high affinity, with the result that LAP and TGFβ remain associated after cleavage. This assemblage is referred to as the small latent complex (SLC), as when in this complex TGFβ cannot bind to its cell surface receptors (20). Structural studies have shown that TGFβ adopts a similar structure in the free, latent, and receptor bound states, but when bound to LAP, the TGFβ receptor binding sites are shielded by regions of the propeptide (21). Simultaneously with pro-TGFβ dimerisation in the ER, a single latent TGFβ binding protein (LTBP) also binds the pro-TGFβ complex via disulfide bonds with LAP (22, 23). The assemblage of LTBP and the SLC is referred to as the large latent complex (LLC).

Figure 1. Simplified scheme of TGFβ secretion and signalling.

A summary of key steps in TGFβ production and signalling. Starting at the bottom left; TGFβ associates with LTBPs inside the cell to form the large latent complex (LLC). After secretion the LLC is localized to ECM fibres via LTBP mediated interactions. Active TGFβ may be released by a number of factors reviewed here. TGFβ can induce down stream signalling by binding its type 1 and type 2 receptors. The canonical signalling pathway involves phosphorylation of R-SMADs by the type I TGFβ receptor. Phosphorylated R-SMADs (pSMAD2/3) interact with SMAD4 and are translocated to the nucleus, where they regulate the transcription of many genes through interactions with CAGA repeat elements. Various nuances of TGFβ signalling have been excluded here for the purposes of simplicity.

Before TGFβ signalling occurs, the growth factor must be released from its latent complex; a process referred to as activation, and a variety of molecules have been implicated as catalysing this process (discussed later) (20). Once released from its LAP “straightjacket”, the TGFβ dimer forms a complex with two TGFβ type II (TGFβRII) and two TGFβ type I (TGFβRI) cell surface receptors that are both serine/threonine kinases (24). Complex formation between TGFβ and its receptors leads to phosphorylation of the inactive TGFβRI by the constitutively active TGFβRII. TGFβRI then phosphorylates SMAD2 and SMAD3 proteins that transmit the TGFβ signal to the nucleus by association with co-SMADs and binding to specific CAGA nucleotide repeats (25). These intracellular signalling pathways and their structural mechanisms have been reviewed elsewhere (10, 26). Other non-canonical signalling pathways may also be activated by TGFβ, which trigger phosphorylation events that appear to bypass SMAD signalling (27).

Signalling by free TGFβ may be modulated by other molecules, such as collagen and decorin, that bind active TGFβ [3]. The “type III” TGFβ receptor (beta-glycan) can also facilitate TGFβ presentation to type I and II receptors (28). Once activated TGFβ does not persist in the ECM and is rapidly cleared from the extracellular space, although the mechanisms mediating this clearance are not well understood.

2. Evolution and diversification of bona fide TGFβ ligands

Members of the TGFβ superfamily have existed since the early evolution of the animal kingdom and are found in the simplest metazoans, such as the sponge (29) and the comb jelly fish (30). Previous studies have examined the evolution of the superfamily, and identified several potential subfamilies (1, 31). However “bona fide” TGFβ growth factors are unique in covalently binding LTBP to form a large latent complex, as well as having several other distinguishing characteristics; such as specifically binding type I and II TGFβ receptors and being rendered latent by pro-peptide binding.

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using TGFβ superfamily protein sequences from a wide variety of organisms (Figure 2) (search methods detailed in supplementary information). Sequences from a broad range of metazoan’s were included in the tree, but only proteins from the deuterostome1 genomes were found to comprise the true TGFβ subtree (Figure 2B). The closest TGFβ homologues in protostomes2, cnidarians3, and other more basal metazoans located to different sub-trees, and often displayed closer homology with the activin or myostatin like proteins. The sea urchins and acorn worms are the most evolutionarily distant organisms from humans in which a true TGFβ homologue is found. The urchin TGFβ orthologue only displays 31% homology with human TGFβ1, while the acorn worm TGFβ displays 38% homology with human TGFβ1, but in phylogenetic trees both are consistently clustered within the bona fide TGFβ sub-tree (Figure 2B). Both Sea squirt and lancelet genomes also contain a single bona fide TGFβ gene.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic tree of the TGFβ superfamily.

A) Phylogenetic tree of 359 TGFβ sequences from a variety of organisms (for search and tree construction methods see supplementary information). To save space sub-trees are compressed and labelled according to the predominant superfamily members they contain. Sub-trees are coloured depending on the pattern of cysteines present in the mature growth factor domains (colour code at bottom). The vertical dimension of each sub-tree is dependent on the number of sequences it contains. Bootstrapping values are shown at each node, and the scale bar at the bottom gives the average number of amino acid substitutions per site. B) The expanded sub-tree of bona fide TGFβ homologues. Sub-trees corresponding to TGFβ1, 2 and 3 isoform groups are highlighted with coloured boxes. Despite the wide range of animal genomes searched, only sequences from the deuterostomes are found in the true TGFβ sub tree.

Lampreys are more closely related to fish and humans than sea squirts and lancelets, and their genome contains two TGFβ sequences, one of which is more closely homologous to TGFβ2 and 3 than TGFβ1 (Figure 2B). Generally the TGFβ2 and 3 isoforms cluster to a separate sub tree (consistent with previous reports (1, 31)). This suggests that these isoforms are more closely related to each other than to TGFβ1, and that TGFβ2 and 3 may have resulted from a secondary gene duplication event that occurred after the divergence of lamprey and jawed vertebrates. Bony fish possess all three TGFβ isoforms and even some additional TGFβ genes. The abundance of TGFβ isoforms in fish may stem from the occurrence of two genome duplication events during bony fish evolution (32), which could have created a number of redundant TGFβ isoforms that were subsequently lost in some species but retained in others. Reptile, bird and mammal genomes all have the standard complement of three TGFβ isoforms, but the amphibian Xenopus Tropicalis appears to lack a TGFβ3-like protein.

As well as providing a timeline for growth factor emergence and diversification, these varied TGFβ sequences can be used to examine the biological importance of specific residues based on their conservation, and thereby highlight fundamental elements of TGFβ biology.

3. Structure, folding and secretion of TGFβ

3.1 Disulfide formation in TGFβ

The correct formation of disulfide bonds is a critical factor in the folding and secretion of many extracellular proteins, as unpaired cysteines may disrupt folding or lead to protein aggregation, resulting in the misfolded protein being retained by proof reading elements of the ER (33). The C-terminal growth factor region of pro-TGFβ contains nine cysteines, eight of which form intra-molecular disulfides and one of which forms an intermolecular disulfide at the dimerisation interface of the mature growth factor. This pattern of cysteines is conserved in many TGFβ superfamily members (shown by sub-tree colours in Figure 2A). However, the pattern of cysteine residues in LAP is considerably more variable.

Each TGFβ1 LAP polypeptide contains three cysteines, one of which forms a disulfide bond with LTBP (discussed later), and the other two form intermolecular dimerisation links in the “bow-tie” region of the LAP1 structure (Figure 3A) (21). Human TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 LAPs contain additional cysteine residues for which the disulfide-bonding pattern has not been mapped. Homology models of the TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 growth factor-LAP complexes indicate that the additional cysteines found in β2 and β3 LAPs are likely located near LAP dimerisation interfaces (Figure 3A). This suggests that they form additional crosslinks between the LAP monomers. These isoform-specific patterns of cysteine residues are conserved across various species (Figure 3B), and no TGFβ1 protein has a cysteine at a position equivalent to C89/91 of human TGFβ2/3, no TGFβ1 or 3 has a CXCC motif equivalent to TGFβ2, and only TGFβ3 proteins have a cysteine equivalent to Cys 123 in human TGFβ3. Although this pattern could be coincidental, it may act as a mechanism to prevent TGF-β isoform heterodimerization, as it is unlikely that any heterodimeric combination of TGFβ1, 2 or 3 could support disulfide formation between all LAP cysteines. Therefore heterodimeric LAP complexes could end up misfolded and retained in the cell.

Figure 3. LAP cysteines.

A) Structure of TGFβ1 and homology models of TGFβ2 and 3 with LAP cysteines highlighted as spheres. TGFβ1 LAP is coloured orange while the growth factor is coloured dark red, TGFβ2 LAP is coloured light green and the growth factor is coloured dark green, and TGFβ3 LAP is coloured light blue and the growth factor is coloured dark blue. B) Alignments of cysteine containing regions, residues are highlighted blue if >60% conserved or yellow if a cysteine residue. Cysteines not conserved in over 60% of sequences are highlighted in pale orange. Specific cysteines of interest are numbered above human TGFβ1, TGFβ2 and TGFβ3 sequences (as highlighted in A).

TGFβ proteins that diverged before the appearance of multiple TGFβ isoforms, also have a distinct pattern of cysteine residues in their pro-peptides; urchin, acorn worm, lancelet and sea squirt sequences all possess a cysteine equivalent to the TGFβ2/3 C89/91, but lack the second cysteine of the CXC bow tie motif, suggesting this additional disulfide is not essential for the structural stability of LAP in these more distant species. The biological importance of LAP’s structural stability is highlighted by Camurati Engelmann disease, where mutations affecting residues in TGFβ1-LAP cause a dominant disorder characterised by bone thickening and pain, especially in the shafts of the long bones (34–36). Many of the disease causing substitutions replace conserved residues (Data not shown), including cysteines and charged amino acids that form salt bridges, which may therefore disrupt LAP structure and TGFβ activation (34–36).

3.2 Interaction of TGFβ with LTBP

A key feature that distinguishes true TGFβ’s from other TGFβ superfamily members is their ability to covalently bind LTBPs. This is thought to occur through disulfide bond formation between cysteine 33 of the TGFβ1 propeptides, and the 2–6 disulfide pair of the third 8-cys/second TB domain of LTBP (37–40). Replacement of cysteine 33 with serine in mouse TGFβ1 produces a phenotype similar to TGFβ1 knockout mice, although less severe (41). All complete bona fide TGFβ sequences identified here contain a conserved cysteine in this position (Figure 4A), whereas an equivalent cysteine is not present in related TGFβ super family members (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Conservation of TGFβ residues interacting with LTBP.

A) Alignment of the N-terminus of the TGFβ propeptide showing absolute conservation of cysteine 33, highlighted in yellow. Residues highlighted blue are also conserved in >75% or more of the sequences. Orange arrows at the top of the alignment highlight residues that when mutated disrupt LTBP1 binding. The grey arrow highlights arginine 58, which when mutated to alanine did not affect LTBP binding B) Alignment with other TGFβ superfamily members. Some members do possess cysteines in this region of sequence, but they do not align well with the conserved features of bona fide TGFβ. C) Structure of TGFβ-LAP (red and orange) and LTBP1 TB2 (blue), TGFβ residues that when mutated inhibit the LAP-LTBP1 interaction are highlighted as orange spheres. Residues in LTBP1 8-Cys3/TB2 that have been shown to contribute to TGFβ binding are highlighted as dark blue spheres. (Carbon atoms coloured as described, while all oxygen atoms are coloured red, nitrogen atoms coloured blue, and sulphur atoms coloured yellow)

The conservation of a cysteine at a position analogous to human TGFβ1 C33 suggests that covalent attachment of TGFβ to LTBP, or another protein, has occurred since the early evolution of the growth factor and represents a fundamental element of TGFβ function. Interestingly, LTBP-like sequences are also first seen in the deuterostomes and can be found in sea urchin and acorn worm genomes (42) (Figure 5). This indicates that LTBPs emerged on a very similar timescale to true TGFβs, and that these two proteins may have co-evolved to perform their specific functions.

Figure 5. Emergence of TGFβ and regulatory factors.

Representation of the proteins present in various organisms selected to give a comprehensive overview of bona fide TGFβ evolution. The tree (top) illustrates the evolutionary relationships between each organism (according to the tree of life web project). The column below each illustrated organism shows whether or not the gene of interest is present, as indicated by a + or -, or other details such as the names of specific isoforms. Blocks of colour highlight where each gene emerges. Details on the methodologies and data used to construct this figure are described in supplementary material.

Mutagenesis studies have identified a number of basic residues in the TGFβ1 propeptide that are important for complex formation with LTBP1 (43). These residues are highly conserved (highlighted with arrows and orange spheres in Figure 4A and 4C). However, in the crystal structure of the SLC, many of these residues are buried by interactions between the pro-peptide and growth factor region of TGFβ (Figure 4C). Therefore, it is unclear whether they are conserved due to their importance in binding the growth factor or due to a role in LTBP interaction.

Other studies have identified key sequence features in the 3rd 8-cys/2nd TB domain of LTBPs that facilitate binding to TGFβ LAP. One of these features is the insertion of two amino acids into the β sheet region prior to the 7th cysteine (figure 4C) (38, 39). The solution structure of this domain indicates that the two amino acid insertion exposes the 2–6 disulfide bond, making it available to react with the propeptide of TGFβ (40). These inserted residues are not found in the equivalent domain in LTBP2, which does not to bind TGFβ (38, 39). Several acidic residues also surround the exposed 2–6 disulfide bond in LTBP1 8-Cys3/TB2, and substitution of these residues with alanine inhibits interaction with LAP (39), consistent with charge interactions between basic residues in LAP and acidic residues in LTBP1. Analysis of LTBP sequences through evolution shows strict conservation of these sequence features in LTBP1 and LTBP3, as well as in urchin, acorn worm, and lancelet LTBP-like proteins (Figure 6), suggesting a conserved LTBP-TGFβ interaction in these species and supporting the co-evolution of these two proteins.

Figure 6. Alignment of LTBP 8-cys3/TB2 domains.

Black arrowheads highlight acidic residues implicated in binding the TGFβ propeptide (numbered according to Chen et al.), and the 2 amino acid insert shown to be important for TGFβ binding is surrounded by a black box. Residues present in >60% of all sequences are highlighted as blue, or yellow when cysteine. Sequences from a variety of organisms representing all LTBP isoforms were aligned with the MEGA 5 BLOSUM matrix (Gap opening penalty 5, gap extension penalty 0.5). Alignment divided into blocks by LTBP isoform.

The 3rd 8-cys/ 2nd TB domain of human LTBP4 binds the TGFβ1 pro-peptide weakly, and does not interact with the LAPs of TGFβ 2 or 3 (39). Some results also suggest TGFβ binding is restricted to the long isoform of LTBP4 (44). This poor binding maybe due to the 3rd 8-cys/ 2nd TB domain of human LTBP4 lacking several key acidic residues (39), which are also absent in LTBP4 sequences from a number of organisms, and in Xenopus tropicalis the critical two amino acid insert is also missing (Figure 6). This suggests the primary biological function of LTBP4 may not be TGFβ binding. On the other hand LTBP2-like proteins only seem to lose the critical amino acid insertion in mammals, and LTBP2 sequences from birds, reptiles, and fish all have the dipeptide insertion and sufficient acidic residues to support hypothetical TGFβ binding.

The biological importance of LTBP1 and LTBP3 is underlined by several mouse model studies. Mice with exons specific to the long isoform of LTBP1 knocked out display lethal defects in cardiovascular development, and defective TGFβ signalling (45, 46). LTBP3 knock out mice show a variety of skeletal defects, including kyphosis, and an osteopetrosis-like phenotype accompanied by reductions in phosphorylated SMAD2/3 in bone (47–50). Studies in zebra fish have also implicated an LTBP3-like protein as important in cardiac development (51), while in humans LTBP3 null mutations are associated with oligodontia (52), suggesting variation of the functional niche occupied by this protein through evolution. The phenotypes of LTBP1 and LTBP3 deficient mice do not clearly reflect those seen in TGFβ-deficient animals, but as both LTBP1 and LTBP3 can bind all three TGFβ isoforms, and are both widely expressed (23), there may be significant redundancy between these LTBPs in TGFβ signalling, which complicates interpretations of phenotype.

3.3 Interaction of TGFβ with GARP

Recently, the glycoprotein-A repetitions predominant protein (GARP) has been shown to bind to TGFβ (53), GARP is a trans membrane leucine rich repeat protein unrelated to the LTBPs. GARP presents TGFβ on the surface of regulatory T-cells and platelets (54, 55), and may assist integrin mediated activation of covalently bound TGFβ when attached to the cell membrane (53). It is thought that the biological role of the GARP-TGFβ complex is focused on immune regulation, as GARP expression appears to be restricted to regulatory T cells and platelets (56), whereas LTBPs are expressed ubiquitously (57). From an evolutionary perspective GARP-like proteins appear limited to gnathostomes4 (Figure 5, and data not shown) suggesting that this protein performs a more specialised role in TGFβ regulation, which may have evolved along with the more complex vertebrate immune system.

4. Storage of latent TGFβ in the ECM

As well as assisting secretion of TGFβ, LTBPs localise TGFβ to extracellular matrix fibers (58–63). Specific interactions have been demonstrated between N-terminal regions of LTBP1, 2, and 4 and fibronectin (62, 63) and between the C-termini of LTBP1, 2 and 4 and the N-terminus of fibrillin (59–61, 64).

Co-localization of LTBP1 with fibronectin is observed in immature fibroblast cultures (58), and fibronectin is essential for initial matrix incorporation of LTBP1 in culture (65). Pull-down assays have demonstrated an interaction between N-terminal fragments of LTBP1 and full-length fibronectin (62), and heparan sulphate proteoglycans may mediate this interaction (66). A fibronectin network is also essential for integrin αvβ6-mediated TGFβ activation in culture (62) (discussed in more detail later). LTBP is a substrate for crosslinking to the ECM by transglutaminase (67), and the inhibition of tissue transglutaminase can prevent TGFβ activation in cell culture (68), although whether covalent crosslinking of LTBP1 to the ECM is essential for activation has not been directly tested. The importance of TGFβ linkage to LTBP for activation in vivo is inferred from the phenotype of the TGFβ1 C33S mice, which is similar to that seen in TGFβ1 null animals (41). As C33S TGFβ is still secreted by cells but gives a TGFβ1 null-like phenotype, attachment to LTBP or other factors must play a critical role in the extracellular activity of TGFβ1.

The most evolutionarily distant fibronectin-like protein, with a complete set of FN type 1, 2 and 3 domains, is found in sea squirts (69), and no true fibronectin-like protein sequences are found in lancelets, urchins or acorn worms (Figure 5) (70, 71). This suggests that fibronectin emerged after the evolution of the LLC. Fibrillin, on the other hand, is a much more ancient ECM protein and has changed very little in its domain organization since its emergence prior to the split of cnidaria and bilateria (42, 72). Fibrillin is structurally related to the LTBPs, and it is likely that the LTBPs evolved from a duplication of an ancestral fibrillin gene (42). The interacting regions of LTBP and fibrillin have many conserved surface residues, which are not found in other structurally homologous domains (42, 73) and could be important for the LTBP-fibrillin interaction (42). From the available sequences we can speculate that an LTBP - fibrillin interaction evolved on a similar timescale to the LLC.

Many observations point towards an in vivo connection between ECM integrity and proper TGFβ signalling. Specifically, Marfan syndrome is a genetic disease caused by dominant mutations in the fibrillin1 gene that results in excess activation of latent TGFβ (74, 75). This condition has a number of symptoms, including aortic dilatation and dissection, long bone overgrowth, and lens dislocation. A number of these symptoms, including aortic dissection, are seen in patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome, who have heterozygous mutations in TGFβ receptor genes (76, 77). Patients with heterozygous mutations in the TGFβ2 gene also suffer from aortic dissection and other MFS like symptoms (78, 79). Additionally antagonism of TGFβ signalling in mouse models of Marfan syndrome restores normal development in multiple tissues and prevents aortic dissection (80–82), suggesting a clear link between the fibrillin matrix and TGFβ signalling.

5. Activation of TGFβ

The trigger of the TGFβ signalling cascade is not the release of the growth factor from cells, but liberation from its latent extracellular complex by latent TGFβ activators. In the following sections a number of activators are reviewed, paying particular attention to their evolutionary history and the availability of in vivo data to validate their biological significance. The proposed activation mechanisms are also evaluated in light of the available structural data.

5.1 Integrins

The cell surface integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8 are well-established activators of TGFβ (83–85). Other αv integrins have also been reported to interact with, and in some cases activate, TGFβ-LAP (86–91). Integrins release TGFβ by two different mechanisms classified as protease-independent and protease-dependent activation.

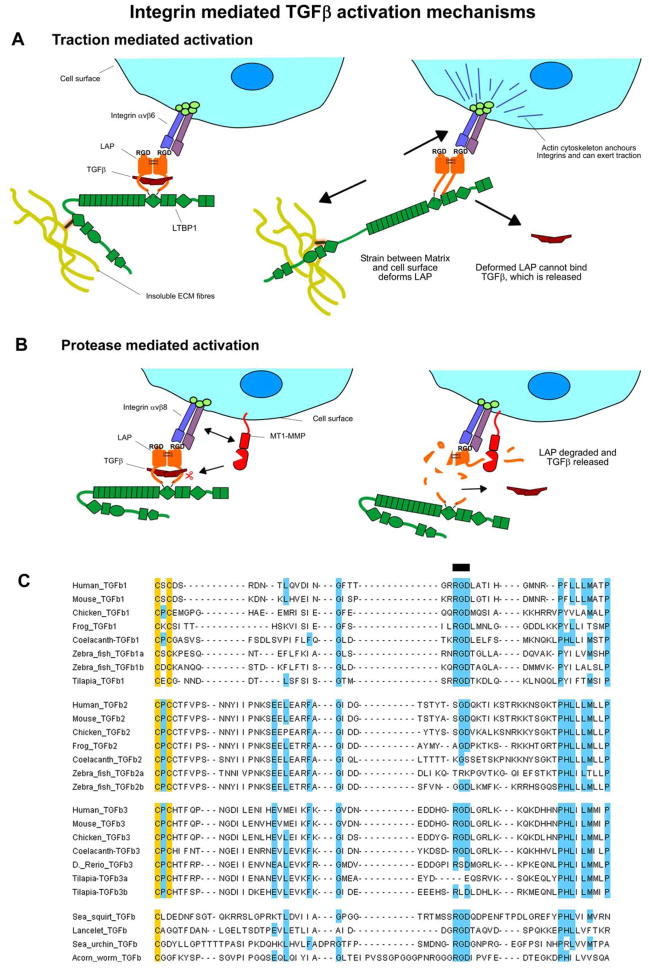

Protease-independent TGFβ activation was first identified with αvβ6 integrin over-expressing cells that activated latent TGFβ1 even in the presence of protease inhibitors (83). This TGFβ1 activation was dependent on covalent attachment of TGFβ1-LAP to LTBP1 (92), attachment of integrin to the actin cytoskeleton (92), specific ECM binding regions of LTBP1 (92), and the presence of a fibronectin matrix (62). An activation mechanism that explains these results is that traction between the cell surface and the insoluble ECM is transmitted to the large latent complex by LTBP and integrins, and liberates active TGFβ by deforming LAP (62, 90, 92, 93) (Figure 7A). This notion is supported by the integrin-dependent release of active TGFβ by contracting myofibroblasts (90), and force dependant release of active TGFβ by integrin coated ferromagnetic beads added to a cell free matrix containing latent TGFβ (93).

Figure 7. Integrin mediated TGFβ activation mechanisms.

A) Scheme for traction mediated activation by integrins. On the left the large latent complex is shown in a “resting” state with integrin binding LAP via its RGD motif. On the right the latent complex is shown under traction, which deforms LAP and releases active TGFβ. Components are labelled within the figure. B) Scheme for protease mediated integrin activation. On the left the integrin is shown binding to LAP at the cell surface. This integrin may then recruit proteases that degrade LAP and release active TGFβ, as shown on the right. C) Alignment of the RGD containing region of TGFβ. Residues conserved in >60% or more of sequences were highlighted blue, or yellow if cysteine, a black line above the alignment highlights the RGD motif.

Cells expressing integrin αvβ8 also activate latent TGFβ, but activation is blocked by the presence of matrix metalloprotease (MMP) inhibitors or when the membrane bound MT1-MMP is knocked down (85). This suggests an alternative protease-dependant mechanism of integrin-based activation involving recruitment of both the latent TGFβ complex and metalloproteases by integrins to facilitate LAP cleavage and release of TGFβ (Figure 7 B).

The significance of integrin-based activation was demonstrated in vivo by the phenotype of a mouse in which the integrin binding RGD motif in TGFβ1 LAP was replaced with an RGE sequence (94, 95). These mice phenocopy TGFβ1 null mice, displaying severe tissue inflammation and a lack of Langerhans cells. As the mutant TGFβ protein is secreted normally, this phenocopy demonstrates that the integrin-binding motif in TGFβ1 is essential for proper TGFβ function. Knocking out or pharmacologically inhibiting integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8 results in vascular phenotypes similar to those seen with Tgfb1RGE/RGE Tgfb3−/− double null mice (94, 95). As TGFβ3 also contains an RGD motif, it is possible that αVβ6 and αVβ8 integrins are the primary activators of both cytokines.

The evolutionary significance of integrin binding by TGFβ is reflected in the strict conservation of the RGD motif in TGFβ proteins from evolutionarily distant organisms such as urchins and acorn worms (Figure 7 C). α and β integrins themselves are extremely ancient molecules, and are present in sponges and some bacteria and fungi. Sponge integrins also bind to RGD-like sequences (96). This evolutionary analysis shows that integrins have the potential to be one of the earliest TGFβ activators, as they were present in the common ancestor of deuterostomes, and the functional RGD sequence is conserved in at least one TGFβ isoform of every species examined. TGFβ2 proteins, on the other hand, consistently lack an RGD motif in the integrin-binding region, and activation of TGFβ2 by integrins has not been reported. This means TGFβ2 may have its own distinct mechanisms of activation that evolved after its split from TGFβ1.

5.2 Proteases

Numerous proteases activate TGFβ in vitro, but as many of these proteases cleave multiple substrates and can exhibit significant redundancy it is difficult to delineate their importance for in vivo TGFβ activation. Proteases may also work in concert with other factors that can provide substrate specificity, as seen with MT1-MMP and integrin αvβ8.

Interpreting the in vivo significance of MT1-MMP in TGFβ signalling is difficult, as while MT1-MMP knock out mice display osteopenia, dwarfism, and fibrosis, these phenotypes are believed to be due to a deficiency in collagen turn over, another substrate of MT1-MMP (97). Although specific cleavage motifs are not well defined, MT1-MMP shows a preference for PXXL sequences or similar motifs (98) which can be found in TGFβ sequences (discussed below). Blast searches located MT1-MMP-like sequences in a number of distantly related organisms, including the cnidarians (Figure 5), suggesting MT1-MMP-like proteases were present when the TGFβ-LTBP system first evolved.

MMP2 and MMP9 activate TGFβ when localized by CD44 on the surface of tumour cells (99). MMP2 and MMP9 have differing expression patterns during development (100), but both appear to have very similar substrate specificities (98, 101), and PXXL like motifs are particularly favoured as with MT1-MMP. Searches of TGFβ sequences reveal numerous potential MMP2/9/MT1-MMP cleavage sites throughout TGFβ proteins, but of particular interest is the presence of relatively well-conserved PXXV putative cleavage motifs in the “latency lasso” region of all three TGFβ isoforms (Figure 8 Ai). Sites on this loop should be exposed to the solvent (Figure 8 Aii), and cleavage of the latency lasso could split LAP into two low affinity fragments allowing TGFβ release. However MMP2 and 9 diverged from the MMP family relatively late in vertebrate evolution (Figure 5), and would not have been present in early deuterostomes to activate TGFβ. Also mice lacking both MMP2 and MMP9 display relatively mild phenotypes that do not reflect a TGFβ deficiency (100). Interestingly MMP2 and MT1-MMP double knockout mice die immediately after birth, but their defects do not closely resemble those seen in TGFβ-deficient animals (102). Together the evolutionary and in vivo evidence does not support MMP2 or 9 playing widespread roles in TGFβ activation.

Figure 8. Conservation of protease cleavage sites in TGFβ and LTBP1.

Ai) Alignments of the “latency lasso” region of LAP. Some potential MMP2/9 cleavage sites are boxed, and pairs of light red or dark red asterisks above the human TGFβ2 sequence highlight two potential MMP cleavage PxxV motifs. Aii) Homology model of TGFβ2, with LAP shown in light green, and the mature growth factor in dark green. The side chains of the two putative PxxV cleavage motifs highlighted in A) are shown as red coloured spheres. B) Sequence alignments of LTBP regions where putative BMP1 sites were detected (103). Residues present in 60% or more sequences are highlighted. The aspartate residues that define the putative cleavage sites are highlighted by boxes, but do not appear to be well conserved.

BMP1 is another metalloprotease implicated in TGFβ activation (103). BMP1 cleavage of LTBP1 is proposed to release the latent complex from the ECM and lead to subsequent TGFβ activation (103). Mice that have BMP1 and the closely related tolloid1 (Tll1) protease knocked out display excessive accumulation of LTBP1 in embryonic tissues and reduced pSMAD2/3 staining suggesting defective TGFβ activation (103). BMP1 and Tll1 also play important roles in processing other extracellular proteins, such as collagen and chordin, and knockouts of BMP1 or Tll1 are embryonic lethal (104). This makes it difficult to assess the in vivo significance of BMP1 or Tll1 for TGFβ activation, and leaves the possibility that the observed accumulation of LTBP1 and the reduction in pSMAD2/3 in BMP1/Tll1 null animals is an indirect consequence of the altered ECM environment, since these enzymes are important regulators of matrix assembly. Members of the BMP1/tolloid family are present throughout metazoan evolution (Figure 5), and therefore have the potential to be ancient TGFβ activators. However the aspartate residues that define putative BMP1 cleavage sites are not well conserved in LTBP1 (103) (Figure 8 B), making a conserved role for BMP1 seem less likely.

An array of serine, cysteine and aspartyl proteases also activate TGFβ. One of the best studied proteolytic activators of TGFβ is the serine protease plasmin (105), which is an important blood protease that degrades various plasma proteins, including fibrin. Plasmin mediates TGFβ activation in co-cultures of endothelial cells and pericytes (106) as well as with retinoid-treated cells (107). Activation in endothelial-pericyte co-cultures is inhibited by antibodies raised against LTBP1 (108) and is dependant on the presence of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor (109), suggesting a role for the cell surface and LTBP. Activated macrophages also activate TGFβ by a mechanism dependent on cell surface localization of plasmin and TGFβ by TSP1 and CD36 (110, 111).

BLAST searches only detected plasmin-like proteins in lancelets and higher organisms (Figure 5), suggesting plasmin-like proteases emerged after TGFβ and LTBP. Also despite the body of evidence demonstrating the role of plasmin in TGFβ activation in cell culture, mice deficient in plasmin develop normally and are viable (112). This lack of TGFβ related phenotypes rules out a non-redundant role for this protease in TGFβ activation.

Another group of serine proteases implicated in TGFβ activation are the kallikreins. These proteases have been suggested to play a role in TGFβ mediated immunosuppression in seminal plasma (113), and LPS impairment of liver regeneration (114). However previous analysis of kallikrein evolution has shown these proteases only emerged and diversified with the tetrapods (115) (supported by searches performed here (Figure 5)), making their evolution quite recent.

Many other extracellular and intracellular proteases have been shown to activate TGFβ in vitro, including cysteine proteases, such as calpain (116), and aspartyl proteases, such as cathepsin D (117), as well as several other serine and metallo-proteases (reviewed elsewhere) (111, 118). Many of these proteases are intracellular and have diverse substrates, and as their in vivo role in TGFβ activation has not been assessed, their evolution is not reviewed here.

5.3 De-glycosylation

Another group of proteins reported to enhance TGFβ activation are the deglycosidases. Early experiments demonstrated that Endoglycosidase F activated TGFβ (119), and more recently Influenza neuramidase has been shown to activate TGFβ by de-glycosylation (120, 121). Human TGFβ1 possesses three potential N-glycosylation sites, as does TGFβ2, while TGFβ3 has two sites. Sequence alignments demonstrate that only the first glycosylation site is conserved across all TGFβ isoforms in all species (Figure 9 A). This site is close to the “latency lasso” region of LAP (Figure 9 B) where there are putative MMP cleavage sites (Figure 8 A). Thus glycosylation might obstruct cleavage of protease sensitive regions of LAP, and sugar removal would enhance protease cleavage. However this conserved glycosylation site may also be important for TGFβ folding or cellular trafficking, as its removal caused an 85% decrease in TGFβ secretion (122). While de-glycosidase-dependent activation may be biologically relevant in influenza infection, there is currently no data supporting a role for deglycosidases in TGFβ activation during developmental or homeostatic processes.

Figure 9. Glycosylation of TGFβ.

A) Alignments of N-glycosylation sites from all human TGFβ isoforms, residues conserved in 60% or more sequences are highlighted blue. Putative N-glycosylation sites are boxed. Only the first glycosylation site is well conserved. B) Glycosylation sites highlighted on the structure of TGFβ1. TGFβ and LAP are coloured as in previous figures and sugar moieties are shown coloured pink and represented as spheres. In the crystallised protein the third glycosylation site, “NNS” has been replaced with “QDS”, but the Q residue is coloured pink here and shown in stick representation labelled “N”176. The position of the RGD motif is also highlighted by a black line, although it is not resolved in the structure.

5.4 Other protein factors

As well as integrins, proteases, and deglycosidases, additional proteins have been implicated as TGFβ activators. Thrombospondin 1 (TSP1) has been the subject of many conflicting studies on its role in TGFβ signalling. Addition of exogenous TSP1 to cell cultures and to latent TGFβ in vitro has been reported to release the active growth factor (123), and interactions of TSP1 with both active TGFβ (124) and LAP (125, 126) have been observed in biochemical assays. Peptide studies have suggested the TGFβ activation sequence in TSP1 is an RFK motif between the first and second TSP1 domains (127), as a “KRFK” containing peptide activates TGFβ at pM concentrations (128) and inhibits TSP1 binding. Further peptide inhibition experiments defined potential interactions between the RFK motif of TSP1 and the LSKL motif in the N-terminus of LAP (125). The TSP1 RFK motif is absent from TSP2, and TSP2 does not activate TGFβ (128). However, some groups have failed to observe TGFβ activation in response to exogenous TSP1 (129), and SPR studies have not clearly demonstrated the interaction of TSP1 with LAP, LAP-TGFβ or TGFβ alone (130). Also platelet α-granules (a rich source of TSP1) have been shown to activate TGFβ just as efficiently if derived from WT or TSP1 null animals (131).

TSP1 knockout mice exhibit mostly normal development, although they do suffer from severe lung inflammation (132) and have other histological abnormalities that partially overlap with the phenotype of TGFβ1 null mice (3, 133). Improved histology was seen in Tsp1−/− animals treated with the TGFβ activating KRFK peptide, while treatment of WT mice with the LAP-like LSKL peptide resulted in increased inflammation (133). However Tsp1−/− null mice fail to mimic all of the features of TGFβ1 nulls. Moreover in vitro TSP1 and the KRFK peptide also activated TGFβ2 (125), but Tsp1−/− animals did not display any of the serious developmental defects seen in TGFβ2−/− animals.

Evolutionary analysis of the TSPs demonstrates that although TSP-like proteins are present in basal deuterostomes, TSP1-like proteins that contain an “RFK” TGFβ activation sequence are limited to the bony fish and higher organisms (Figure 5 and also observed in a separate study (134)). Together the conflicting biochemical observations, the limited phenotype of TSP1 null mice, and the late evolution of TGFβ activating sequences suggest TSP1 is not a central activator of TGFβ in vivo, although it may still play a role in regulating inflammation or other specific TGFβ activities.

F-spondin (or spondin-1) is another protein containing thrombospondin type 1 domains that has been implicated in TGFβ activation. Specifically F-spondin has been shown to increase TGFβ activity in cartilage explants (135). F-spondin has not yet been shown to directly activate TGFβ in cell-free systems, but its effect on TGFβ activation can be attenuated by an antibody specific to the F-spondin thrombospondin type 1 repeats, suggesting parallels with activation by TSP1. Proteins containing a unique N-terminal “Spondin” like domain can be found in all deuterostomes examined, as well as the cnidarians (Figure 5), suggesting they emerged before TGFβ. However more information is needed on the mechanism by which F-spondin activates TGFβ before any conclusions can be drawn.

Neuropilin (Nrp) has been suggested to act as an activator of latent TGFβ, both on the surface of T-cells (136, 137) and in some tumour lines (137). The mechanism of TGFβ regulation by neuropilin is unclear, as in solid phase assays neuropilin-1 binds mature TGFβ1, LAP, and type I and II TGFβ receptors (137). Nrp is also hypothesized to be a co-receptor for TGFβ (136–138), and may initiate its own intra-cellular signalling cascades. However, neuropilin-like proteins were only detected in lampreys and higher vertebrates, and not in lower deuterostomes (Figure 5), which does not support neuropilin being an ancient activator of TGFβ.

5.5 Physicochemical factors

TGFβ is also released from its latent state by a variety of physicochemical factors, including detergents, UVB and ionising radiation (139–144), reactive oxygen species (145), heat (146), physical shear (147), and extremes of pH (117). The relevance of many of these factors in vivo is unclear, and many are unlikely to be encountered in a physiological context, but potential biological roles for some are discussed below.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) activate TGFβ both in cell culture and in cell free systems (145) and may mediate the effects of ionizing (140) and UVB radiation (139). ROS are also implicated in asbestos mediated TGFβ activation (148), and in immuno-suppression by HIV infected regulatory T-cells (149). Mechanistically ROS are proposed to release TGFβ by catalysing backbone scissions in LAP (145), but this has not been demonstrated directly. One study showed that ROS activation was specific to TGFβ1 (150), and relied on the presence of methionine 253 (150). However, this methionine is confined to mammalian TGFβ1 sequences, which would suggest that ROS sensitivity evolved extremely recently.

Prolonged stirring or physical shear activates a percentage of the TGFβ present in platelet releaseates (147). This activation is dependant on LTBP binding and is not seen with C33S TGFβ (147). The activation mechanism also appears to involve disulfide isomerisation, and is inhibited by the thiol isomerase binding peptide mastoparan (151). No specific residues have yet been defined in TGFβ or LTBP that are responsible for shear-sensing, and the in vivo role of this mechanism remains unknown.

TGFβ activation by low pH (117) could also be relevant in vivo, as physiological micro-environments exist that are sufficiently acidic to activate TGFβ. For example bone resorption by osteoclasts reduces extracellular pH to ~4.5 (152), and osteoclasts can activate TGFβ (153), as do tumour cells that create an acidic microenvironment (154). However, whether the low pH generated by these cells is essential for activation is unknown. No specific residues have been identified in TGFβ that confer pH sensitivity, and without such information it is difficult to assess the physiological significance of pH driven activation.

6. Conclusions

The evolutionary data reviewed here suggests that the first true TGFβ-like growth factor emerged during the early evolution of the deuterostomes. LTBPs appear to have emerged at the same time, and in both TGFβ and LTBP sequences amino acids required for their covalent linkage are extremely well conserved. This suggests the functions of these two proteins may have been intimately connected since their early evolution.

Of the plethora of described TGFβ activators, only a limited number were present when true TGFβ first evolved (Figure 5). This does not dismiss the biological significance of factors that evolved later, but the first TGFβ would have needed an activator, and only factors that were present when TGFβ first emerged could have performed this role. Potential activation mechanisms were also examined by alignments to test the conservation of key residues, although for some activators this analysis was limited by a lack of molecular understanding of the residues involved. Of the factors for which activation is well understood, integrins appear to be clear front-runners for the role of earliest TGFβ activators. As well as being extremely ancient molecules, the RGD integrin-binding motif is found in all the early TGFβ sequences and all TGFβ1 like sequences (Figure 7). The consistent absence of an RGD motif from TGFβ2 could reflect a specific adaptation of this growth factor, which may be activated by alternative mechanisms yet to be elucidated.

A number of other activators, including MT1-MMP, BMP1, and F-Spondin were also present when TGFβ first evolved, but a lack of mechanistic insight into activation by these factors limits their evolutionary analysis, and in vivo data on their role in activation is either absent or inconclusive. Analysis of relatively well-studied activators, such as plasmin and TSP1, demonstrates that these proteins did not emerge until later in deuterostome evolution, suggesting they may have less critical roles in TGFβ activation, consistent with knockout mouse studies.

It has previously been suggested that the complex of TGFβ-LAP-LTBP acts as a “sensor” (20), with release of active TGFβ serving as a readout of the extracellular events that prompted its activation. It is not always clear what events trigger the TGFβ sensor in specific tissue contexts in vivo or how this “triggering” requirement relates to the physiological roles of TGFβ signalling. The evolutionary data presented here suggest that LAP-LTBP, and LAP-integrin interactions may have been the first to evolve when TGFβ broke off from the rest of the superfamily. The establishment of these two interactions should have allowed the early LLC to sense traction between cell surface and the extracellular matrix (Figure 7 A), and it is possible that true TGFβ first evolved as a readout of this cell-ECM traction.

While TGFβ has been the subject of intense research, a clear understanding of the biology of this molecule has been obfuscated by the perplexing array of potential TGFβ activators. The volume of literature on TGFβ may suggest a system of mind-boggling complexity, but TGFβ signalling must have evolved from a simple starting point, and by defining that point we gain a more solid foundation to understand how TGFβ performs its multitudinous roles in development and tissue homeostasis. Placing TGFβ activators within an evolutionary framework also highlights the physiological processes and evolutionary adaptations for which specific TGFβ activators may and may not be essential. A clearer understanding of these processes may suggest specific TGFβ activators as drug targets, and this in turn will enable us to better treat the numerous diseases where the shackles of the beast have been broken.

We acknowledge funding from NIH grants R01 GM083220 (Mechanisms for Latent TGF-β1 Activation In Vivo), R01 CA034282 (Regulation of TGF-β Activity in the Lung by LTBP-4) and P01 AR49698 (Cell signalling and Marfan syndrome)

Supplementary Material

Biographies

Ian Robertson studied for his D. Phil at Oxford University in the lab of Prof Penny Handford, examining the molecular basis for the interaction of LTBP1 and fibrillin1, and more broadly looking at the structure and evolution of these molecules. Having completed his D. Phil in 2012 Ian started a Post doc in the lab of Prof Daniel Rifkin at the New York University school of medicine where he is currently studying a number of aspects of TGFβ biology, but is particularly interested in the biological significance of the extracellular matrix in TGFβ activation.

Daniel Rifkin received his Biochemistry Ph.D. from the Rockefeller University in 1968. Throughout his career he has worked on many aspects of TGFβ signalling and investigated many novel mechanisms of TGFβ activation. He is currently the Charles Aden Poindexter Professor of Medicine at the New York University school of Medicine.

Footnotes

Deuterostomes are organisms where the anus develops before the mouth during gastrulation, and includes mammals, other vertebrates, sea squirts, sea urchins, lancelets and acorn worms.

Protostomes are organisms where the mouth develops before the anus during gastrulation, and includes invertebrates, annelid worms, molluscs and nematodes.

Cnidarians are organisms with a basic body plan consisting of non-living jelly-like “mesoglea”, sandwiched between two epithelial layers. This group includes corals, jellyfish and anemones.

Vertebrates with jaws

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herpin A, Lelong C, Favrel P. Transforming growth factor-beta-related proteins: an ancestral and widespread superfamily of cytokines in metazoans. Dev Comp Immunol. 2004;285:461–85. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahlem P, Newfeld SJ. Informatics approaches to understanding TGFbeta pathway regulation. Development. 2009;13622:3729–40. doi: 10.1242/dev.030320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni AB, Huh CG, Becker D, Geiser A, Lyght M, Flanders KC, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;902:770–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanford LP, Ormsby I, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Sariola H, Friedman R, Boivin GP, et al. TGFbeta2 knockout mice have multiple developmental defects that are non-overlapping with other TGFbeta knockout phenotypes. Development. 1997;12413:2659–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunker N, Krieglstein K. Tgfbeta2 −/− Tgfbeta3 −/− double knockout mice display severe midline fusion defects and early embryonic lethality. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2002;2061–2:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s00429-002-0273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dooley S, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta in progression of liver disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;3471:245–56. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coward WR, Saini G, Jenkins G. The pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2010;46:367–88. doi: 10.1177/1753465810379801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pohlers D, Brenmoehl J, Loffler I, Muller CK, Leipner C, Schultze-Mosgau S, et al. TGF-beta and fibrosis in different organs - molecular pathway imprints. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;17928:746–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burks TN, Cohn RD. Role of TGF-beta signaling in inherited and acquired myopathies. Skelet Muscle. 2011;11:19. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle JJ, Gerber EE, Dietz HC. Matrix-dependent perturbation of TGFbeta signaling and disease. FEBS Lett. 2012;58614:2003–15. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wyss-Coray T, Masliah E, Mallory M, McConlogue L, Johnson-Wood K, Lin C, et al. Amyloidogenic role of cytokine TGF-beta1 in transgenic mice and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1997;3896651:603–6. doi: 10.1038/39321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han G, Li F, Singh TP, Wolf P, Wang XJ. The pro-inflammatory role of TGFbeta1: a paradox? Int J Biol Sci. 2012;82:228–35. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.8.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor beta in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;34218:1350–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;1342:215–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akhurst RJ, Hata A. Targeting the TGFbeta signalling pathway in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;1110:790–811. doi: 10.1038/nrd3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaartinen V, Voncken JW, Shuler C, Warburton D, Bu D, Heisterkamp N, et al. Abnormal lung development and cleft palate in mice lacking TGF-beta 3 indicates defects of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. Nat Genet. 1995;114:415–21. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taya Y, O’Kane S, Ferguson MW. Pathogenesis of cleft palate in TGF-beta3 knockout mice. Development. 1999;12617:3869–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mu Z, Yang Z, Yu D, Zhao Z, Munger JS. TGFbeta1 and TGFbeta3 are partially redundant effectors in brain vascular morphogenesis. Mech Dev. 2008;1255–6:508–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubois CM, Blanchette F, Laprise MH, Leduc R, Grondin F, Seidah NG. Evidence that furin is an authentic transforming growth factor-beta1-converting enzyme. Am J Pathol. 2001;1581:305–16. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63970-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annes JP, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Making sense of latent TGFbeta activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 2):217–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R, Chen X, Mi L, Walz T, et al. Latent TGF-beta structure and activation. Nature. 2011;4747351:343–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyytiainen M, Penttinen C, Keski-Oja J. Latent TGF-beta binding proteins: extracellular matrix association and roles in TGF-beta activation. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2004;413:233–64. doi: 10.1080/10408360490460933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saharinen J, Hyytiainen M, Taipale J, Keski-Oja J. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding proteins (LTBPs)--structural extracellular matrix proteins for targeting TGF-beta action. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;102:99–117. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radaev S, Zou Z, Huang T, Lafer EM, Hinck AP, Sun PD. Ternary complex of transforming growth factor-beta1 reveals isoform-specific ligand recognition and receptor recruitment in the superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2010;28519:14806–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massague J, Chen YG. Controlling TGF-beta signaling. Genes Dev. 2000;146:627–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;1136:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, Holm TM, Aziz H, Schoenhoff F, Bedja D, et al. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science. 3326027:361–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1192152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez-Casillas F, Wrana JL, Massague J. Betaglycan presents ligand to the TGF beta signaling receptor. Cell. 1993;737:1435–44. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adamska M, Degnan SM, Green KM, Adamski M, Craigie A, Larroux C, et al. Wnt and TGF-beta expression in the sponge Amphimedon queenslandica and the origin of metazoan embryonic patterning. PLoS One. 2007;210:e1031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang K, Ryan JF, Baxevanis AD, Martindale MQ. Evolution of the TGF-beta signaling pathway and its potential role in the ctenophore, Mnemiopsis leidyi. PLoS One. 2011;69:e24152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burt DW, Law AS. Evolution of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1994;51:99–118. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braasch I, Salzburger W. In ovo omnia: diversification by duplication in fish and other vertebrates. J Biol. 2009;83:25. doi: 10.1186/jbiol121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagiwara M, Nagata K. Redox-dependent protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum: folding to degradation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;1610:1119–28. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssens K, Vanhoenacker F, Bonduelle M, Verbruggen L, Van Maldergem L, Ralston S, et al. Camurati-Engelmann disease: review of the clinical, radiological, and molecular data of 24 families and implications for diagnosis and treatment. J Med Genet. 2006;431:1–11. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janssens K, Gershoni-Baruch R, Guanabens N, Migone N, Ralston S, Bonduelle M, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the latency-associated peptide of TGF-beta 1 cause Camurati-Engelmann disease. Nat Genet. 2000;263:273–5. doi: 10.1038/81563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinoshita A, Saito T, Tomita H, Makita Y, Yoshida K, Ghadami M, et al. Domain-specific mutations in TGFB1 result in Camurati-Engelmann disease. Nat Genet. 2000;261:19–20. doi: 10.1038/79128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gleizes PE, Beavis RC, Mazzieri R, Shen B, Rifkin DB. Identification and characterization of an eight-cysteine repeat of the latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein-1 that mediates bonding to the latent transforming growth factor-beta1. J Biol Chem. 1996;27147:29891–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saharinen J, Keski-Oja J. Specific sequence motif of 8-Cys repeats of TGF-beta binding proteins, LTBPs, creates a hydrophobic interaction surface for binding of small latent TGF-beta. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;118:2691–704. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Ali T, Todorovic V, O’Leary JM, Kristina Downing A, Rifkin DB. Amino acid requirements for formation of the TGF-beta-latent TGF-beta binding protein complexes. J Mol Biol. 2005;3451:175–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lack J, O’Leary JM, Knott V, Yuan X, Rifkin DB, Handford PA, et al. Solution structure of the third TB domain from LTBP1 provides insight into assembly of the large latent complex that sequesters latent TGF-beta. J Mol Biol. 2003;3342:281–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshinaga K, Obata H, Jurukovski V, Mazzieri R, Chen Y, Zilberberg L, et al. Perturbation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1 association with latent TGF-beta binding protein yields inflammation and tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;10548:18758–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805411105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson I, Jensen S, Handford P. TB domain proteins: evolutionary insights into the multifaceted roles of fibrillins and LTBPs. Biochem J. 2011;4332:263–76. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walton KL, Makanji Y, Chen J, Wilce MC, Chan KL, Robertson DM, et al. Two distinct regions of latency-associated peptide coordinate stability of the latent transforming growth factor-beta1 complex. J Biol Chem. 2010;28522:17029–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kantola AK, Ryynanen MJ, Lhota F, Keski-Oja J, Koli K. Independent regulation of short and long forms of latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP)-4 in cultured fibroblasts and human tissues. J Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Todorovic V, Frendewey D, Gutstein DE, Chen Y, Freyer L, Finnegan E, et al. Long form of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 (Ltbp1L) is essential for cardiac outflow tract septation and remodeling. Development. 2007;13420:3723–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.008599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Todorovic V, Finnegan E, Freyer L, Zilberberg L, Ota M, Rifkin DB. Long form of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 (Ltbp1L) regulates cardiac valve development. Dev Dyn. 2011;2401:176–87. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, Dabovic B, Colarossi C, Santori FR, Lilic M, Vukmanovic S, et al. Growth retardation as well as spleen and thymus involution in latent TGF-beta binding protein (Ltbp)-3 null mice. J Cell Physiol. 2003;1962:319–25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dabovic B, Chen Y, Colarossi C, Obata H, Zambuto L, Perle MA, et al. Bone abnormalities in latent TGF-[beta] binding protein (Ltbp)-3-null mice indicate a role for Ltbp-3 in modulating TGF-[beta] bioavailability. J Cell Biol. 2002;1562:227–32. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colarossi C, Chen Y, Obata H, Jurukovski V, Fontana L, Dabovic B, et al. Lung alveolar septation defects in Ltbp-3-null mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;1672:419–28. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62986-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dabovic B, Levasseur R, Zambuto L, Chen Y, Karsenty G, Rifkin DB. Osteopetrosis-like phenotype in latent TGF-beta binding protein 3 deficient mice. Bone. 2005;371:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou Y, Cashman TJ, Nevis KR, Obregon P, Carney SA, Liu Y, et al. Latent TGF-beta binding protein 3 identifies a second heart field in zebrafish. Nature. 2011;4747353:645–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noor A, Windpassinger C, Vitcu I, Orlic M, Rafiq MA, Khalid M, et al. Oligodontia is caused by mutation in LTBP3, the gene encoding latent TGF-beta binding protein 3. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;844:519–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang R, Zhu J, Dong X, Shi M, Lu C, Springer TA. GARP regulates the bioavailability and activation of TGFbeta. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;236:1129–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tran DQ, Andersson J, Wang R, Ramsey H, Unutmaz D, Shevach EM. GARP (LRRC32) is essential for the surface expression of latent TGF-beta on platelets and activated FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;10632:13445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stockis J, Colau D, Coulie PG, Lucas S. Membrane protein GARP is a receptor for latent TGF-beta on the surface of activated human Treg. Eur J Immunol. 2009;3912:3315–22. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang R, Wan Q, Kozhaya L, Fujii H, Unutmaz D. Identification of a regulatory T cell specific cell surface molecule that mediates suppressive signals and induces Foxp3 expression. PLoS One. 2008;37:e2705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) binding proteins: orchestrators of TGF-beta availability. J Biol Chem. 2005;2809:7409–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unsold C, Hyytiainen M, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Keski-Oja J. Latent TGF-beta binding protein LTBP-1 contains three potential extracellular matrix interacting domains. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 1):187–97. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Massam-Wu T, Chiu M, Choudhury R, Chaudhry SS, Baldwin AK, McGovern A, et al. Assembly of fibrillin microfibrils governs extracellular deposition of latent TGF beta. J Cell Sci. 123(Pt 17):3006–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isogai Z, Ono RN, Ushiro S, Keene DR, Chen Y, Mazzieri R, et al. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding protein 1 interacts with fibrillin and is a microfibril-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 2003;2784:2750–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ono RN, Sengle G, Charbonneau NL, Carlberg V, Bachinger HP, Sasaki T, et al. Latent transforming growth factor beta-binding proteins and fibulins compete for fibrillin-1 and exhibit exquisite specificities in binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2009;28425:16872–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809348200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fontana L, Chen Y, Prijatelj P, Sakai T, Fassler R, Sakai LY, et al. Fibronectin is required for integrin alphavbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta complexes containing LTBP-1. FASEB J. 2005;1913:1798–808. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4134com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kantola AK, Keski-Oja J, Koli K. Fibronectin and heparin binding domains of latent TGF-beta binding protein (LTBP)-4 mediate matrix targeting and cell adhesion. Exp Cell Res. 2008;31413:2488–500. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirani R, Hanssen E, Gibson MA. LTBP-2 specifically interacts with the amino-terminal region of fibrillin-1 and competes with LTBP-1 for binding to this microfibrillar protein. Matrix Biol. 2007;264:213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zilberberg L, Todorovic V, Dabovic B, Horiguchi M, Courousse T, Sakai LY, et al. Specificity of latent TGF-ss binding protein (LTBP) incorporation into matrix: role of fibrillins and fibronectin. J Cell Physiol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jcp.24094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Q, Sivakumar P, Barley C, Peters DM, Gomes RR, Farach-Carson MC, et al. Potential role for heparan sulfate proteoglycans in regulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) by modulating assembly of latent TGF-beta-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;28236:26418–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nunes I, Gleizes PE, Metz CN, Rifkin DB. Latent transforming growth factor-beta binding protein domains involved in activation and transglutaminase-dependent cross-linking of latent transforming growth factor-beta. J Cell Biol. 1997;1365:1151–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kojima S, Nara K, Rifkin DB. Requirement for transglutaminase in the activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta in bovine endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;1212:439–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tucker RP, Chiquet-Ehrismann R. Evidence for the evolution of tenascin and fibronectin early in the chordate lineage. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;412:424–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tucker RP, Drabikowski K, Hess JF, Ferralli J, Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Adams JC. Phylogenetic analysis of the tenascin gene family: evidence of origin early in the chordate lineage. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hynes RO. The evolution of metazoan extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 2012;1966:671–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piha-Gossack A, Sossin W, Reinhardt DP. The evolution of extracellular fibrillins and their functional domains. PLoS One. 2012;73:e33560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jensen SA, Robertson IB, Handford PA. Dissecting the fibrillin microfibril: structural insights into organization and function. Structure. 2012;202:215–25. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robinson PN, Arteaga-Solis E, Baldock C, Collod-Beroud G, Booms P, De Paepe A, et al. The molecular genetics of Marfan syndrome and related disorders. J Med Genet. 2006;4310:769–87. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.039669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dietz HC, Loeys B, Carta L, Ramirez F. Recent progress towards a molecular understanding of Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;139C1:4–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Attias D, Stheneur C, Roy C, Collod-Beroud G, Detaint D, Faivre L, et al. Comparison of clinical presentations and outcomes between patients with TGFBR2 and FBN1 mutations in Marfan syndrome and related disorders. Circulation. 2009;12025:2541–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Loeys BL, Chen J, Neptune ER, Judge DP, Podowski M, Holm T, et al. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Nat Genet. 2005;373:275–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lindsay ME, Schepers D, Bolar NA, Doyle JJ, Gallo E, Fert-Bober J, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TGFB2 cause a syndromic presentation of thoracic aortic aneurysm. Nat Genet. 2012;448:922–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boileau C, Guo DC, Hanna N, Regalado ES, Detaint D, Gong L, et al. TGFB2 mutations cause familial thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections associated with mild systemic features of Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;448:916–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE, Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, et al. Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;333:407–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohn RD, van Erp C, Habashi JP, Soleimani AA, Klein EC, Lisi MT, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade attenuates TGF-beta-induced failure of muscle regeneration in multiple myopathic states. Nat Med. 2007;132:204–10. doi: 10.1038/nm1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Cooper TK, et al. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science. 2006;3125770:117–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;963:319–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Annes JP, Rifkin DB, Munger JS. The integrin alphaVbeta6 binds and activates latent TGFbeta3. FEBS Lett. 2002;5111–3:65–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mu D, Cambier S, Fjellbirkeland L, Baron JL, Munger JS, Kawakatsu H, et al. The integrin alpha(v)beta8 mediates epithelial homeostasis through MT1-MMP-dependent activation of TGF-beta1. J Cell Biol. 2002;1573:493–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wipff PJ, Hinz B. Integrins and the activation of latent transforming growth factor beta1 - an intimate relationship. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;878–9:601–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Munger JS, Harpel JG, Giancotti FG, Rifkin DB. Interactions between growth factors and integrins: latent forms of transforming growth factor-beta are ligands for the integrin alphavbeta1. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;99:2627–38. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lu M, Munger JS, Steadele M, Busald C, Tellier M, Schnapp LM. Integrin alpha8beta1 mediates adhesion to LAP-TGFbeta1. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 23):4641–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ludbrook SB, Barry ST, Delves CJ, Horgan CM. The integrin alphavbeta3 is a receptor for the latency-associated peptides of transforming growth factors beta1 and beta3. Biochem J. 2003;369(Pt 2):311–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wipff PJ, Rifkin DB, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol. 2007;1796:1311–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tatler AL, John AE, Jolly L, Habgood A, Porte J, Brightling C, et al. Integrin alphavbeta5-mediated TGF-beta activation by airway smooth muscle cells in asthma. J Immunol. 2011;18711:6094–107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Annes JP, Chen Y, Munger JS, Rifkin DB. Integrin alphaVbeta6-mediated activation of latent TGF-beta requires the latent TGF-beta binding protein-1. J Cell Biol. 2004;1655:723–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Buscemi L, Ramonet D, Klingberg F, Formey A, Smith-Clerc J, Meister JJ, et al. The single-molecule mechanics of the latent TGF-beta1 complex. Curr Biol. 2124:2046–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yang Z, Mu Z, Dabovic B, Jurukovski V, Yu D, Sung J, et al. Absence of integrin-mediated TGFbeta1 activation in vivo recapitulates the phenotype of TGFbeta1-null mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;1766:787–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aluwihare P, Mu Z, Zhao Z, Yu D, Weinreb PH, Horan GS, et al. Mice that lack activity of alphavbeta6- and alphavbeta8-integrins reproduce the abnormalities of Tgfb1- and Tgfb3-null mice. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 2):227–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.035246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wimmer W, Perovic S, Kruse M, Schroder HC, Krasko A, Batel R, et al. Origin of the integrin-mediated signal transduction. Functional studies with cell cultures from the sponge Suberites domuncula. Eur J Biochem. 1999;2601:156–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Holmbeck K, Bianco P, Caterina J, Yamada S, Kromer M, Kuznetsov SA, et al. MT1-MMP-deficient mice develop dwarfism, osteopenia, arthritis, and connective tissue disease due to inadequate collagen turnover. Cell. 1999;991:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D343–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGFbeta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;142:163–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garg P, Vijay-Kumar M, Wang L, Gewirtz AT, Merlin D, Sitaraman SV. Matrix metalloproteinase-9-mediated tissue injury overrides the protective effect of matrix metalloproteinase-2 during colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;2962:G175–84. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90454.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Turk BE, Huang LL, Piro ET, Cantley LC. Determination of protease cleavage site motifs using mixture-based oriented peptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;197:661–7. doi: 10.1038/90273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oh J, Takahashi R, Adachi E, Kondo S, Kuratomi S, Noma A, et al. Mutations in two matrix metalloproteinase genes, MMP-2 and MT1-MMP, are synthetic lethal in mice. Oncogene. 2004;2329:5041–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ge G, Greenspan DS. BMP1 controls TGFbeta1 activation via cleavage of latent TGFbeta-binding protein. J Cell Biol. 2006;1751:111–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pappano WN, Steiglitz BM, Scott IC, Keene DR, Greenspan DS. Use of Bmp1/Tll1 doubly homozygous null mice and proteomics to identify and validate in vivo substrates of bone morphogenetic protein 1/tolloid-like metalloproteinases. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;2313:4428–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.13.4428-4438.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lyons RM, Gentry LE, Purchio AF, Moses HL. Mechanism of activation of latent recombinant transforming growth factor beta 1 by plasmin. J Cell Biol. 1990;1104:1361–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.4.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Antonelli-Orlidge A, Saunders KB, Smith SR, D’Amore PA. An activated form of transforming growth factor beta is produced by cocultures of endothelial cells and pericytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;8612:4544–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kojima S, Rifkin DB. Mechanism of retinoid-induced activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta in bovine endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 1993;1552:323–32. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041550213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]