Abstract

Few studies examine normative developmental processes among teenage mothers. Framed from a risk and resilience perspective, this prospective study examined the potential for ethnic identity status (e.g., diffuse, achieved), a normative developmental task during adolescence, to buffer the detrimental effects of discrimination on later adjustment and self-esteem in a sample of 204 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Ethnic discrimination was associated with increases in depressive symptoms and decreases in self-esteem over time, regardless of ethnic identity status. However, ethnic discrimination was only associated with increases in engagement in risky behavior among diffuse adolescents, suggesting that achieved or foreclosed identities buffered the risk of ethnic discrimination on later risky behavior. Findings suggest that ethnic identity resolution (i.e., the component shared by those in foreclosed and achieved statuses) may be a key cultural factor to include in prevention and intervention efforts aimed to reduce the negative effects of ethnic discrimination on later externalizing problems.

Keywords: Latina adolescents, teen parenting, ethnic discrimination, ethnic identity, risky behavior

Mexican-origin1 females experience disparate rates of poor mental health (Anderson & Mayes, 2010), are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (e.g., illicit drug and alcohol use, physical fights; CDC, 2007), and have the highest teenage pregnancy birthrate of all ethnic groups in the U.S. (88.7 per 1,000 births; CDC, 2011). Further, Mexican-origin adolescent mothers experience heightened risk of poverty (Berry, Shillington, Peak, & Hohman, 2000), which has been linked to adverse psychosocial well-being (e.g., Kurtz & Derevensky, 1994). From a risk and resilience perspective (e.g., Rutter, 1987), these disparities warrant attention to the processes and factors that may place these young women at risk, in addition to the potential protective factors that may ameliorate stress and enhance well-being.

In addition to undergoing the non-normative transition to parenthood during adolescence, teenage mothers are also negotiating normative developmentally driven processes that become increasingly salient during adolescence, such as identity formation. The integration of normative developmental processes (e.g., focusing on risk and/or protective factors and processes) within the study of a high-risk population, such as Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, will allow for a more holistic understanding of their lives, including appropriate ways to build on normative developmental strengths and prevent negative outcomes that stem from risk. Guided by the risk and resilience perspective (Rutter, 1987), this study examined ethnic discrimination as one culturally-salient explanation for the disparate rates of health and well-being experienced by Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Although discrimination is just one of many risk factors and cultural stressors that contribute to negative outcomes, it is a pervasive occurrence among Latinos in the U.S. (e.g., Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegria, 2008; Romero & Roberts, 2003a) and has been linked to numerous negative outcomes (e.g., Flores, Tschann, Dimas, Pasch, & de Groat, 2010; Romero & Roberts, 2003a; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007).

Given the negative consequences of discrimination for Mexican-origin adolescents, identifying potential buffers of this risk is critical from a risk and resilience perspective (e.g., Rutter, 1987). Ethnic identity is one culturally salient and developmentally relevant factor that may buffer the risk of ethnic discrimination on well-being and self-esteem (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012). Research with samples of Mexican-origin youth has documented that ethnic identity can buffer the negative effects of discrimination on well-being (e.g., Greene et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Wong, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2012); however, this work has only examined ethnic identity affirmation (i.e., positive/negative feelings about one’s ethnicity) and has not examined the buffering potential of ethnic identity exploration (i.e., seeking information and knowledge about one’s ethnic group) or ethnic identity resolution (i.e., one’s confidence about the feeling one has about one’s ethnic identity). These normative developmental features of ethnic identity are particularly salient during adolescence, especially among Latina adolescents (Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). Further, to date, we are not aware of any study that has examined the interaction between ethnic discrimination and ethnic identity statuses (i.e., diffuse, foreclosed, moratorium, achieved; Phinney, 1993) within a high-risk sample, such as adolescent mothers.

This study sought to expand upon previous research via two main goals. First, we examined whether ethnic discrimination was prospectively associated with adjustment problems among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Second, we examined ethnic identity status as a potential buffer of the negative effects of ethnic discrimination on later depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and engagement in risky behaviors.

Ethnic Identity as a Buffer

Adolescence marks a critical point for identity development (Erikson, 1968), particularly because youth are increasingly able to think about abstract concepts due to significant cognitive maturity that occurs in this developmental period. For ethnic minority youth, normative development also involves culturally salient issues such as ethnic identity development (Umaña -Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gomez, 2004). Building on theoretical work on identity (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1980) and Phinney’s (1989) early work on ethnic identity, individuals’ ethnic identity can be conceptualized as fitting into one of four identity statuses by examining the individual’s degree of exploration and resolution: diffuse, foreclosed, moratorium, and achieved. Individuals characterized as having a diffuse ethnic identity report low exploration and low resolution, whereas those characterized as foreclosed report low exploration and high resolution. Additionally, individuals that report high exploration and low resolution are characterized as in moratorium, whereas those that report high exploration and resolution are characterized as achieved. Theoretical notions of identity and empirical research do suggest that exploration without commitment (e.g., moratorium status) is normative during middle to late adolescence (e.g., Quintana, 2007), and that a diffuse status is normative in early adolescence. The linear nature of this conceptualization has been criticized given that research has found that individuals may depart from the linear sequence (e.g., Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006). Nonetheless, given that there appears to be individual and developmental differences in how adolescents develop their ethnic identities, it is important to understand the impact of ethnic identity exploration and resolution in a more nuanced way, such as examining how the combination of one’s levels of exploration and resolution inform adjustment.

Indeed, researchers have found mean level differences in adjustment based on ethnic identity status groups. For instance, one study found that African American adolescents(aged 11–17 years) with achieved ethnic identities reported better psychological adjustment compared to those in other statuses and that youth with foreclosed identities reported better adjustment compared to diffuse youth (e.g., Seatonet al., 2006). Similarly, research with Navajo adolescents found that achieved youth reported higher self -esteem and social functioning than youth who were categorized in diffuse, moratorium, or foreclosed statuses (Jones & Galliher, 2007). Nonetheless, these studies have only examined ethnic identity status as a promotive factor of healthy adjustment where as the current study examines ethnic identity status as a protective factor that may disrupt the link between ethnic discrimination and later adjustment. That is, it may be the case that one’s ethnic identity status may interact with experiences of discrimination in a way that produces more positive adjustment in the context of risk (e.g., a protective effect). This may be the case because adolescents who have explored and come to resolution about their ethnic identities (i.e., achieved youth) may feel more confident and secure about their ethnic identity, which may in turn aid in the buffering of stress related to their ethnicity. Further, those who have not explored or come to a resolution about their ethnic identities (i.e., diffuse youth) may have fewer cultural resources to draw upon during stressful events related to their ethnicity, which may enhance the association between discrimination and adjustment.

The risk and resilience perspective (e.g., Rutter, 1987) suggests that individual characteristics and contextual factors can facilitate a process that leads to healthy adjustment in spite of adverse conditions, such as discrimination. The individual characteristics or environmental factors that mitigate risk are referred to as protective factors (Rutter, 1987). In this study, ethnic identity is conceptualized as a protective factor, which may mitigate the negative effects of discrimination on later depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and engagement in risky behavior.

Adolescent Motherhood

With respect to the specific population of interest in the current study, Mexican-origin females are at heightened risk for teenage pregnancy (CDC, 2011), which places them at increased risk for poverty and lower educational attainment (Berry et al., 2000). In addition to their risk status as teen mothers, poverty is particularly high among Mexican-origin individuals in the U.S. (23.5% compared to the national average of 12.4%; Ramirez, 2004). The additional complexity of the intersection of teenage pregnancy and minority status in the U.S. warrants further consideration of how social experiences and developmental processes intersect. That is, Mexican-origin mothers must negotiate social experiences, such as discrimination, and normative developmental tasks, such as identity development, simultaneously while transitioning into their role as a parent.

Finally, normative adolescent developmental tasks, such as ethnic identity exploration may be particularly salient for young women making the non-normative transition to parenthood in adolescence. For example, it is possible that adolescent mothers are more aware of and engaged in the process of ethnic identity formation because as they transition to the role of motherhood they may be keenly aware of the gender-driven expectations others have of them to be the carriers of culture and to inculcate their cultural values to their children (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). Thus, the current study will examine the degree to which Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ ethnic identity status may buffer the negative effects of discrimination on adjustment.

The Current Study

The current study examined the prospective associations between discrimination and three indicators of well-being among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. To date, we are not aware of any longitudinal study that has examined whether ethnic discrimination is associated with poorer well-being for adolescent mothers over time. Second, we examined if ethnic identity status reduced the detrimental effects of discrimination on adjustment. Consistent with prior work on identity (Jones & Galliher, 2007; Marcia, 1980; Seaton et al., 2006), we expected that an achieved identity (high on exploration and resolution) would be protective for well-being whereas a diffuse identity (low on exploration and resolution) would not (Jones & Galliher, 2007; Seaton et al., 2006). Further, given some evidence that a foreclosed identity is more promotive of well-being than a diffuse identity (e.g., Seaton et al., 2006), we expected that a foreclosed identity would also function in a protective way. In addition, we expected that youth who had explored their ethnic identity but had not yet come to a resolution about their identity (i.e., moratorium status) may be protected from the negative effects of discrimination because they are gaining the tools and knowledge necessary to buffer the effects of these negative experiences (e.g., greater self-esteem; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007).

Method

Sample

The current study included 204 Mexican-origin adolescent mothers participating in an ongoing longitudinal study of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their infants. Adolescents were recruited into the study during their third trimester of pregnancy and ranged in age from 15 to 18 years (MWave 1= 16.80 years, SD = 1.00). The majority (64.7%) of adolescents were born in the U.S.; adolescents who were not U.S. born had lived in the U.S. for an average of 12.84 years (SD = 5.13). Most adolescents co-resided with their mother figures (87%) at Wave 1 of the study, and the average household size at Wave 1 was 4.84 people (SD = 2.51). The average household income was $27,323 (SD = $19,893), computed by creating a sum of adolescents’ mother figures’ annual income, funds received by others who contributed to the household, and public financial assistance (i.e., public assistance, food stamps) at Wave 1. Nearly 19% of adolescents were employed (n = 38) at Wave 1 and reported an average hourly wage of $6.78 (SD = $3.47). At Wave 1, over half (58.3%) of the adolescents were attending school, 4.9% had already graduated or received their GED, and over one-third (36.8%) had dropped out of school.

Procedure

Pregnant adolescents were recruited from community agencies and schools in a Southwestern region of the U.S. that served the target population. Staff members distributed brochures that described the study in both English and Spanish to adolescents at these locations. Adolescents who were interested returned a contact card, and a follow-up screening call was conducted by bilingual staff to assess eligibility. Eligibility criteria included that the adolescent: identify as Mexican origin, be 15 to 18 years old, not be legally married, and have a mother figure who was willing to participate in the study. Of the 321 adolescents who expressed interest in the study, 305 were contacted to assess eligibility (the additional 16 adolescents could not be reached due to disconnected phone numbers). Of those adolescents, 80% (n = 207) met the study criteria and agreed to participate. Three families of the original 207 were omitted from the longitudinal sample due to an unexpected death of a participating family member.

Data were collected using in-home interviews that lasted approximately two and a half hours. All interviewers were female and interviews were conducted in either English (61%) or Spanish (39%). Wave 1 of the study was conducted when the adolescent was in her third trimester of pregnancy (Mean = 31.2 weeks, SD = 4.40) and Wave 2 interviews were conducted when the adolescent’s child was 10 months old. Approximately 96% of the sample was retained at Wave 2.

Measures

Study measures were translated into Spanish and back translated into English by two separate individuals; discrepancies that arose between the two translators were resolved following the guidelines outlined by Knight, Roosa, and Umaña-Taylor (2009). Higher scores on all scales indicate higher levels of the construct.

Ethnic identity

Ethnic identity was assessed at Wave 1 using the exploration (7 items; “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity”) and resolution (4 items; “I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me”) subscales of the Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Items were scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale and Cronbach’s αs were .80 (exploration) and .85 (resolution). Ethnic identity statuses were derived from the use of exploration and resolution scores in cluster analysis (described below).

Perceived discrimination

Ethnic discrimination was assessed at Wave 1 using a revised version of the Perceived Discrimination Scale (Whitbeck, Hoyt, McMorris, Chen, & Stubben, 2001) adapted for use with Latino populations (Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). The 10-item scale assesses experiences with ethnic discrimination in school, with authority figures, and globally. Items (e.g., “How often has the police hassled you because you are Hispanic/Latino?”) were coded on a 4-point Likert-type scale and Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Adolescent adjustment

Adolescent adjustment was assessed at Waves 1 and 2 via measures of: self-esteem (10-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; Rosenberg, 1979), depressive symptoms (20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; Radloff, 1977), and engagement in risky behavior (24-item measure developed for the Michigan Study of Adolescent Transitions; Eccles & Barber, 1990). Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable for measures of self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and engagement in risky behaviors at Wave 1 (.78, .89, .89, respectively) and Wave 2 (.81, .87, .89, respectively).

Plan of Analysis

The analysis had two main steps. First, we utilized cluster analysis to identify the ethnic identity clusters (using the exploration and resolution subscales) at Wave 1. Ward’s hierarchical method of cluster analysis with squared Euclidian distances for estimation was used (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Dendogram and cluster distances were examined to determine the most appropriate number of clusters. After an acceptable number of clusters was determined, ethnic identity exploration and resolution means were assessed by ANOVA to determine the conceptual adequacy of the solution. As suggested by Aldenderfer and Blashfield (1984), validation of the cluster solution using two random subsets of the sample (50% and 75%) was conducted using the Monte Carlo procedure. In this case, the K-means cluster technique was used to analyze the random subsets. Cluster membership of the two solutions from the Monte Carlo analyses were compared to the initial cluster membership obtained from the full sample.

Second, after participants were classified into an ethnic identity status, we explored our research questions using longitudinal multiple-group path analysis in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010) with ethnic identity status at Wave 1 as the grouping variable. Specifically, we examined whether the associations between Wave 1 ethnic discrimination and our three indicators of adjustment at Wave 2 (i.e., self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and engagement in risky behavior) were moderated by ethnic identity status. All outcomes were tested simultaneously, allowing for the natural covariation between our outcomes to be represented in the results. Furthermore, our model controlled for Wave 1 levels of the outcome variables, allowing us to predict change over time in the dependent variables as a function of ethnic discrimination. Nested model comparisons were used to examine whether or not paths differed by ethnic identity status; for this test, if the chi-square difference was significant then the constraints were not tenable suggesting that there was moderation by group membership. In comparison, if the chi-square difference test was not significant, the associations were assumed to be equal amongst all groups. Final model fit was assessed using the chi-square, root-mean-squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI) (Kline, 2011). All analyses controlled for age, adolescent nativity (0 = born outside of the U.S., 1 = born in the U.S.), and Wave 1 assessments of our outcomes of interest. Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML; Arbuckle, 1996; Schafer & Graham, 2002) was used to account for missing data. Descriptive statistics for all study constructs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Key Study Constructs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W1 Age | --- | ||||||||||

| 2. W1 Household Income | 0.11 | --- | |||||||||

| 3. W1 EI Exploration | −0.02 | −0.02 | --- | ||||||||

| 4. W1 EI Resolution | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.51*** | --- | |||||||

| 5. W1 Ethnic Discrimination | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | --- | ||||||

| 6. W1 Depressive Symptoms | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.07 | 0.25*** | --- | |||||

| 7. W1 Self-Esteem | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.29*** | 0.39*** | −0.11 | −0.49*** | --- | ||||

| 8. W1 Risky Behavior | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.41*** | 0.37*** | −0.24*** | --- | |||

| 9. W2 Depressive Symptoms | −0.00 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.34*** | 0.54*** | −0.34*** | 0.34*** | --- | ||

| 10. W2 Self-Esteem | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.14* | −0.27*** | −0.45*** | 0.61*** | −0.31*** | −0.56*** | --- | |

| 11. W2 Risky Behavior | −0.13 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.13 | 0.32*** | 0.25*** | −0.31*** | 0.52*** | 0.38*** | −0.28*** | --- |

|

| |||||||||||

| Mean | 16.80 | 27323.73 | 2.87 | 3.28 | 1.34 | 0.89 | 3.23 | 1.51 | 0.87 | 3.26 | 1.32 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.00 | 19893.30 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.31 |

| Skewness | .10 | 1.71 | −.06 | −.86 | 2.03 | .74 | −.24 | 1.53 | .56 | −.57 | 1.81 |

Note. EI = ethnic identity. W1 = wave 1. W2 = wave 2.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results

Ethnic Identity Cluster Analysis

Based on the initial dendogram and cluster distances, a three group solution appeared to be the most appropriate cluster solution. After examining the means of the three groups in comparison to the overall sample means of ethnic identity exploration and resolution (see Table 2), the solution was deemed to be conceptually interpretable. That is, the cluster analysis revealed a diffuse group, a foreclosed group, and an achieved group, which are consistent with ethnic identity theory and previous research (e.g., Jones & Galliher, 2007; Marcia, 1980; Seaton et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). An examination of the means for each cluster compared to the overall sample mean provides some validity to our solution (see Table 2). Post-hoc analyses using ANOVA revealed that all three clusters were significantly different from one another on mean levels of ethnic identity exploration (F = 222.82, p < .001, η2 = .69) and ethnic identity resolution (F = 168.07, p < .001, η2 = .63). According to Cohen (1988), an eta-squared (η2) effect size of greater than or equal to .26 is considered large; thus, the mean level differences between groups on ethnic identity exploration and resolution were large. Additionally, the average agreement between cluster membership solutions from the Monte Carlo procedure was consistent 78% of the time (based on an average of two iterations using 50% and 75% of the data); this level of agreement is consistent with previous studies that have used the same procedure to examine the reliability of cluster solutions (e.g., Scottham, Cooke, Sellers, & Ford, 2010).

Table 2.

Ethnic Identity Exploration and Resolution Means and Standard Deviations by Cluster

| N (%) | Exploration | Resolution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1: Diffuse | 43 (21%) | 2.26 (.42) | 2.16 (.42) |

| Cluster 2: Foreclosed | 100 (49%) | 2.63 (.51) | 3.48 (.45) |

| Cluster 3: Achieved | 61 (30%) | 3.69 (.28) | 3.76 (.29) |

|

| |||

| Overall Sample Mean | 2.87 (.70) | 3.28 (.72) | |

Multiple-Group Path Analysis

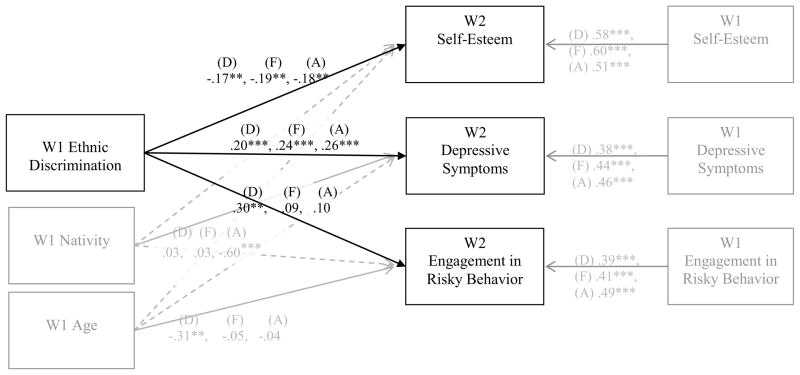

We next tested a series of nested multiple-group path models, with W1 ethnic identity status as the grouping variable, to examine whether the associations among W1 ethnic discrimination and later (W2) self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and engagement in risky behaviors differed by ethnic identity status (i.e., diffuse, foreclosed, and achieved). An initial model was fit so that all pathways were freely estimated across all groups. This model had poor fit (χ2 (df = 33) = 53.581, p < .05; RMSEA = .10 [90% C.I. = .04 – .14]; CFI = .932). Next, we constrained the pathway from discrimination to self-esteem to be equal across groups. The difference in chi-square values relative to the change in degrees of freedom was not significant (Δχ2 (Δdf = 2) = 1.564, p > .05), suggesting that the association between discrimination and self-esteem did not differ by ethnic identity status. Thus, across ethnic identity status groups, ethnic discrimination significantly predicted decreases in self-esteem over time, although small in nature (β’s ranged from −.17 to −.19). While keeping this constraint, we next constrained the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms to be equal across ethnic identity status groups. Similarly, the change in chi-square values was not significant (Δχ2 (Δdf = 2) = 0.433, p > .05), suggesting that the association between discrimination and depressive symptoms was not moderated by ethnic identity status. Again, across ethnic identity statuses, discrimination predicted increases in depressive symptoms over time, albeit the effect size was small (β’s ranged from .20 to .26). Finally, keeping both of the prior constraints in the model, we constrained the pathway between discrimination and engagement in risky behavior. In this case, the difference in chi-square values was significant (Δχ2 (Δdf = 2) = 7.094, p < .05), suggesting that the path could not be constrained to be equal across groups because the association between discrimination and engagement in risky behavior differed by ethnic identity status. A series of post-hoc tests revealed that the path could be constrained for the foreclosed and achieved groups, but not for the diffuse group (Δχ2 (Δdf = 1) = 6.352, p < .05). The final model (shown in Figure 1) had excellent model fit (χ2 (df= 54) = 66.19, p = .12; RMSEA = .06 [90% C.I. = .00 – .10]; CFI = .96) and suggested that the association between discrimination and risky behaviors was significant, moderately-sized, and positive for diffuse adolescents (β = .30), but there was no significant association between discrimination and later engagement in risky behaviors for foreclosed or achieved ethnic identity statues.

Figure 1.

Results from the Multiple Group Path Analysis.

Note. Standardized coefficients are shown. Control variables are presented in light grey. D = Diffuse, F = Foreclosed, A = Achieved. Covariation among the outcomes was modeled but is not shown here for brevity. Dashed lines represent non-significant pathways and solid lines represent significant pathways. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study contributes to research on ethnic discrimination and adjustment by examining these associations among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers during the initial transition to parenthood. Consistent with prior research that documents the detrimental association between discrimination and well-being (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003a; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007), we found that discrimination was moderately associated with later depressive symptoms and self-esteem for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, regardless of ethnic identity status. Further, there was a moderate association between discrimination and increases in risky behavior (Flores et al., 2010), but this significant association was specific to adolescent mothers with a diffuse ethnic identity. Given that both foreclosed and achieved identity statuses were protective against later engagement in risky behavior, this finding underscores the importance of identity resolution for buffering the negative association between discrimination and later externalizing problems.

Ethnic Identity, Discrimination, and Adolescent Adjustment

Prior work has noted that Latino youth may engage in risky behaviors in response to experiences of discrimination (Flores et al., 2010); consistent with this prior work, our findings suggest that risky behaviors (i.e., anger expression, self-medication) may be a coping mechanism that Mexican-origin adolescent mothers utilize in response to ethnic discrimination, particularly among those who lack a strong commitment to their ethnic identity. This finding is consistent with previous findings with non-pregnant Latino adolescents that showed that a stronger commitment to one’s ethnic identity (i.e., resolution) was longitudinally associated with adolescents’ use of proactive coping strategies to deal with ethnic discrimination, regardless of level of ethnic identity exploration (Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). Thus, when faced with ethnic discrimination, youth who have a strong understanding of what their ethnicity means to them and what role ethnicity plays in their lives (i.e., high levels of ethnic identity resolution) may be protected by their heightened sense of confidence in who they are. Specifically, where youth with some level of commitment to their ethnic identity may react to ethnic discrimination more proactively (e.g., Umaña-Taylor et al., 2008), youth who lack commitment may engage in less healthy coping mechanisms in response to discrimination, such as engaging in risky behaviors (e.g., Flores et al., 2010). Importantly, these findings suggest that decreasing substance use and other externalizing behaviors for Mexican-origin adolescents may be possible by providing scaffolding and opportunities to foster ethnic identity resolution. This is a particularly important finding with our sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, given that reducing risky behavior within this population has implications for their own development and well-being, and also for the well-being and development of their children.

Although ethnic identity status played an important role for adolescents’ engagement in risky behavior, ethnic identity status did not buffer the association between ethnic discrimination and later internalizing symptoms or self-esteem, suggesting that future research is needed to identify potential protective factors for Mexican American adolescents’ internalizing problems and self-esteem. Notably, this finding is consistent with a prior study of non-pregnant Mexican-origin youth, such that youths’ cultural orientations and values buffered the link between discrimination and externalizing problems but not internalizing symptoms (Delgado, Updegraff, Roosa, & Umaña-Taylor, 2011). It may be that ethnic identity resolution buffers against the use of maladaptive coping strategies in response to discrimination, but does not affect the strong (and consistently documented) association between discrimination and internalizing problems, which may be more difficult to attenuate. Previous research has found that ethnic identity affirmation is a critical buffer for the link between discrimination and later internalizing problems for non-pregnant adolescents (e.g., Greene et al., 2006); however, prior findings with the current sample of adolescent mothers did not find this buffering effect with affirmation (Umana-Taylor, Updegraff, & Gonzales-Backen, 2011).

Another possibility is that other processes or mechanisms are more salient for disrupting the link between discrimination and internalizing problems. For instance, a recent study found that distraction coping (i.e., engagement in activities in order to take one’s mind off of a stressor) buffered the link between discrimination and internalizing symptoms among Mexican-American youth (Brittian, Toomey, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2013). Thus, because discrimination is an uncontrollable stressor, the use of distraction strategies rather than active coping strategies may help to attenuate this association; yet, future research is needed that assesses the association between coping, discrimination, ethnic identity, and internalizing problems.

Potential Benefits of Foreclosure

Our findings also highlight the positive potential of a foreclosed ethnic identity status in middle to late adolescence, which is particularly important given that nearly 50% of the adolescent mothers in our sample had foreclosed identities. Theoretical models and empirical evidence suggest that individuals with foreclosed identities are characterized by high levels of conformity and obedience, and that these individuals tend to over-identify with their parents (e.g., Côté, 2009); these individuals are often portrayed in the literature as being low in developmental complexity. Further, according to Erikson (1968), successful identity development in adolescence requires that youth differentiate the self from the parent without total disconnection. Yet, other research suggests that for marginalized groups, foreclosure may be beneficial. In fact, certain aspects of the cultural contexts of Mexican-origin youth may foster greater foreclosure (e.g., a greater proportion of youth may be foreclosed who live in ethnic homogenous contexts versus heterogeneous contexts, Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990). That is, for Mexican-origin youth in predominately Mexican communities, foreclosure may be desirable given that it may foster a greater sense of connection to the community and be associated with well-being (e.g., Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990). The majority of adolescents in the current study were contextually located in a Southwestern urban area that has a larger and established Mexican-origin population. Thus, exploration may have little utility when the cultural attitudes, behaviors, and traditions are already engrained in adolescents’ everyday cultural experiences. Future studies need to examine how these processes vary as a function of geographic/sociocultural context. This is an important future direction given that prior studies have found differences in the associations between ethnic identity and self-esteem by geographical/sociocultural location (e.g., Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007).

As noted earlier, the developmental time period captured in the current study (i.e., middle to late adolescence) is a time when exploration increases and is followed by a gradual decrease into adulthood (e.g., French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Pahl & Way, 2006). Yet, none of the adolescent mothers in the current study were identified as being in moratorium, a status characterized by low resolution and high exploration. Further, we found substantially higher levels of ethnic identity resolution in this study compared to previous work with non-pregnant ethnic minority adolescents (i.e., Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Perhaps the transition to parenthood prematurely disrupts normative ethnic identity development in that exploration of ethnicity is put aside until after a period of adjustment to parenthood. That is, perhaps exploration is only afforded to young people who do not have to assume adult roles at an early age, such as parenthood. It is also plausible that when these young women do explore their ethnic identity, they move quickly into high resolution (given that 30% of the participants were identified as achieved).

Future research should investigate the nuances of ethnic identity development for adolescent mothers. For example, longitudinal research could investigate whether the non-normative timing of pregnancy in adolescence accelerates or de-accelerates one’s ethnic identity development. An understanding of how ethnic identity continues to develop after the initial transition to parenthood, which was only 10 months postpartum in the current study, is critical to identifying how their ethnic identity statuses change (i.e., do adolescent mothers begin to explore their ethnic identities more after the initial transition to parenthood resolves?) or remain stable. Finally, comparative research could examine whether trajectories of ethnic identity are substantially different for pregnant versus non-pregnant ethnic minority adolescents.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study significantly adds to the literature on how ethnic discrimination is associated with well-being among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, but it is not without limitations. The study design limits the generalizability of these results to the larger population of Latina adolescents given that it was an ethnically homogeneous design and a high-risk sample of teen mothers. However, the homogenous design is also an important strength of the study, as it allowed us to capture the heterogeneity that exists within this particular ethnic group on experiences with discrimination and ethnic identity, and how these factors are related to well-being during the transition to adolescent motherhood. Our limited focus on Mexican-origin adolescents is also important given that cultural experiences likely vary by different subgroups of Latinos (Baca Zinn & Wells, 2000). Further, we utilized a static measure to arrive at the ethnic identity statuses, which is a limitation given that ethnic identity is dynamic in nature (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Thus, future studies would benefit from a time-intensive, prospective design (e.g., daily diary) that examines the daily or weekly fluctuations in ethnic discrimination, identity, and well-being to capture this dynamic interplay. Nonetheless, our study provides initial evidence that ethnic identity resolution is important for understanding the association between discrimination and later externalizing behaviors.

A second important direction for future research will be to consider how the additive nature of stressors in the lives of adolescent mothers would also provide a more comprehensive understanding of their internalizing problems. For instance, given the potential other stressors in the lives of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers, such as stress related to new parenthood, is there an additive influence that captures the increased risk of internalizing problems? One might expect that for youth who are experiencing high levels of stress related to the transition of pregnancy, the effect of ethnic discrimination on internalizing problems may be less salient.

A final future direction pertains to the need to assess parenthood identity among adolescent mothers. To date, we are unaware of any study that attempts to understand how adolescent parents explore their new identity as a parent, come to a resolution about what their new identity as a parent means to them, and how they feel about their new identity as a parent. In particular, it is intriguing to consider the co-developing nature of ethnic identity and parenthood identity in relation to well-being.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that ethnic discrimination functions in an expected, detrimental manner with Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Although ethnic identity resolution buffered the association between ethnic discrimination and later externalizing problems, it did not buffer this link for internalizing problems or self-esteem. Future prevention and intervention efforts may consider ethnic identity resolution as a potential targeted mechanism for change; nonetheless, more research is needed to identify buffers of discrimination on internalizing problems.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the families who participated in the study.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061376; PI: Umaña-Taylor), the Department of Health and Human Services (APRPA006001; PI: Umaña-Taylor), and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. Additional support for the first author’s time was provided by a National Institute of Mental Health National Research Service Award Training Grant (T32 MH018387).

Footnotes

The term “Mexican-origin” is used to describe the country of origin and/or ancestry of the adolescent participants.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Russell B. Toomey, Email: Russell.Toomey@asu.edu.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Email: Adriana.Umana-Taylor@asu.edu.

Kimberly A. Updegraff, Email: Kimberly.Updegraff@asu.edu.

Laudan B. Jahromi, Email: Laudan.Jahromi@asu.edu.

References

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ER, Mayes LC. Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:338–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M, Wells B. Diversity within Latino families: New lessons for family social science. In: Demo D, Allen K, Fine MA, editors. Handbook of Family Diversity. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 252–273. [Google Scholar]

- Berry EH, Shillington AM, Peak T, Hohman MM. Multi-ethnic comparison of risk and protective factors for adolescent pregnancy. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2000;17(2):79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Brittian AS, Toomey RB, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE. Perceived discrimination, coping strategies, and Mexican origin adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors: Examining the moderating role of gender and cultural orientation. Applied Developmental Science. 2013;17:4–19. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2013.748417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance United States, 2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;57 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/ss/ss5704.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC health disparities and inequalities report – United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(Suppl):1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Côté J. Identity formation and self-development in adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. pp. 266–304. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Discrimination and Mexican-origin adolescents” adjustment: The moderating roles of adolescents’, mothers’, and fathers’ cultural orientations and values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber B. Unpublished scale. University of Michigan; 1990. Risky behavior measure. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Pasch LA, de Groat CL. Perceived racial/ethnic discrimination, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and health risk behaviors among Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57:264–273. doi: 10.1037/a0020026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MD, Galliher RV. Ethnic identity and psychosocial functioning in Navajo adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:683–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00541.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3 . New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Methodological challenges in studying ethnic minority or economically disadvantaged populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz L, Derevensky JL. Adolescent motherhood: An application of the stress and coping model to child-rearing attitudes and practices. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1994;13:5–24. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1994-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcia JE. Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. New York: Wiley; 1980. pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus user’s guide [Sixth Edition] Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x. Advance online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegria M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;9:34–49. doi: 10.1177/0272431689091004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. New York: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(3):259–270. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;7:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez RR. We the people: Hispanics in the United States Census 2000 special reports. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau Department of Commerce; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003a;9:171–184. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the Self. New York: Basic Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottham KM, Cooke DY, Sellers RM, Ford K. Integrating process with content in understanding African American racial identity development. Self and Idnetity. 2010;9:19–40. doi: 10.1080/15298860802505384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Scottham KM, Sellers RM. The status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories, and well-being. Child Development. 2006;77:1416–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Markstrom-Adams C. Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development. 1990;61:290–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02780.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond AB. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Shin N. An examination of the Ethnic Identity Scale with diverse populations: Exploring variation by ethnicity and geography. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:178–186. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination, ethnic identity, acculturation, and self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Garcia CD, Gonzales-Backen M. A longitudinal examination of Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:16–50. doi: 10.1177/0272431607308666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Wong JJ, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE. Ethnic identity and gender as moderators of the association between discrimination and academic adjustment among Mexican-origin adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez MY. Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, Gonzales-Backen MD. Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ stressors and psychosocial functioning: examining ethnic identity affirmation and familism as moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:140–157. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9511-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, McMorris BJ, Chen X, Stubben JD. Perceived discrimination and early substance abuse among American Indian children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:405–424. doi: 10.2307/3090187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]