Abstract

Background Arsenic exposure via drinking water increases the risk of chronic respiratory disease in adults. However, information on pulmonary health effects in children after early life exposure is limited.

Methods This population-based cohort study set in rural Matlab, Bangladesh, assessed lung function and respiratory symptoms of 650 children aged 7–17 years. Children with in utero and early life arsenic exposure were compared with children exposed to less than 10 µg/l in utero and throughout childhood. Because most children drank the same water as their mother had drunk during pregnancy, we could not assess only in utero or only childhood exposure.

Results Children exposed in utero to more than 500 µg/l of arsenic were more than eight times more likely to report wheezing when not having a cold [odds ratio (OR) = 8.41, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.66–42.6, P < 0.01] and more than three times more likely to report shortness of breath when walking on level ground (OR = 3.86, 95% CI: 1.09–13.7, P = 0.02) and when walking fast or climbing (OR = 3.19, 95% CI: 1.22–8.32, P < 0.01]. However, there was little evidence of reduced lung function in either exposure category.

Conclusions Children with high in utero and early life arsenic exposure had marked increases in several chronic respiratory symptoms, which could be due to in utero exposure or to early life exposure, or to both. Our findings suggest that arsenic in water has early pulmonary effects and that respiratory symptoms are a better marker of early life arsenic toxicity than changes in lung function measured by spirometry.

Keywords: Arsenic, lung function, respiratory, pulmonary, in utero, children

Introduction

Environmental exposures may have greater impact on children than on adults, because most organogenesis and organ maturation take place in utero and during childhood.1,2 To date, however, relatively little evidence is available from human studies on the health impact of early life exposure to arsenic in drinking water. Recent studies suggest that arsenic can cause increased mortality from diseases in adulthood following in utero and childhood exposure, including effects in the lung, particularly bronchiectasis and lung cancer.3–5

We believe that the first evidence of arsenic in drinking water causing non-malignant pulmonary effects came from Antofagasta in Chile, when river water with a high concentration (about 850 µg/l) of naturally occurring arsenic was first diverted to the city for use as municipal water supply in 1958. Beginning in 1962, patients with arsenic-caused skin lesions and bronchopulmonary effects, including chronic cough and bronchiectasis, were identified.6,7 Zaldivar reported patients in Antofagasta with arsenic-caused skin lesions and mentioned that bronchitis and bronchiectasis were frequently found.8 After an arsenic treatment plant was installed, which reduced water arsenic concentrations from around 850 µg/l to about 100 µg/l, Zaldivar and Ghai reported a marked reduction in many signs and symptoms, including a reduction in the prevalence of chronically coughing children from 37.9% to 7.0%.9

Following these early reports from Chile, there is a gap in the literature until the findings from arsenic-contaminated tube-well water in West Bengal, India, were reported. We showed that the prevalence of chronic cough and shortness of breath increased with increasing concentrations of arsenic in drinking water in a cross-sectional survey of 7683 participants.10 Findings were most pronounced in those with arsenic-caused skin lesions (e.g., the prevalence odds ratio for chronic cough was 7.8 for women with skin lesions, and 5.0 for men with skin lesions). A smaller cross-sectional survey of 218 participants in Bangladesh also reported increased respiratory symptoms with elevated water arsenic concentrations,11 with greater effects among women than among men.

In India, we found evidence that the impact of arsenic on lung function by spirometry among men was actually greater than that of smoking.12 We also found that study participants in India with arsenic-caused skin lesions had a 10-fold increased prevalence of bronchiectasis compared with subjects who did not have skin lesions.13 In Chile, we found marked increase in mortality from bronchiectasis in young adults aged 30–49 years with potential early life exposure to arsenic (Standardized Mortality Ratio = 46.2).4 These findings, as well as the results from more recent studies showing increased risks of respiratory disease and symptoms in arsenic-exposed populations,3,14–19 highlight the particular susceptibility of the human lung to arsenic toxicity.

We are not aware of any cohort studies of respiratory effects in children who were exposed in utero and in early childhood. One study has followed pregnancies and found increases in lower respiratory tract infections in infants of mothers with high urine arsenic concentrations during pregnancy.20 The objective of our study was to see if pulmonary effects were evident in children aged 7–17 years following in utero and early childhood exposure to arsenic in drinking water. Studying the effects of early life arsenic exposure is a public health priority, since millions of pregnant women and children worldwide are exposed to arsenic in drinking water above the current drinking water guideline of 10 µg/l.

Methods

Study population

The study took place in the Matlab Sub-district of Bangladesh, about 57 km southeast of Dhaka. This study area has a well-established infrastructure for conducting epidemiological studies. The International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), has maintained an internationally recognized and unique prospective Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) in 142 villages of the Matlab region since 1966. The geographical information system component of the surveillance records has spatial information on households and tube-wells used to obtain household water. In 2002–03, icddr,b conducted a population-based survey of all 220 000 Matlab residents, documenting the residential tube-well history of each individual over the age of 5 years at the time. Tube-wells were the main source of drinking water in this area. An important feature of this survey was that it included arsenic measurements for all 13 286 tube-wells in operation in Matlab.

Based on the extensive arsenic water concentration measurements obtained during the 2002–03 survey, we were able to select for the study a cohort of children whose mothers had the highest arsenic exposure during pregnancy, and a cohort of unexposed children whose mothers’ drinking water contained less than 10 µg/l in utero and with no known >10 µg/l exposure during childhood. We first identified in the HDSS records children aged 7–17 years, whose mothers used the highest recorded arsenic water concentrations while these children were in utero, to identify an exposed cohort. For each child identified as exposed in utero, we selected a non-exposed child of the same age and gender with evidence that the water their mother ingested during her pregnancy contained less than 10 µg/l of arsenic, and with no evidence of the child consuming water containing more than 10 µg/l of arsenic since birth. The mothers and children were invited to participate in the study.

Exposure history

Having selected the children using these existing data, we then obtained further detailed arsenic exposure histories for all 650 children. This was accomplished by administering a household questionnaire asking the mothers of all children in our study to provide the location of each residence that they had lived in for at least 6 months, starting from 1 year prior to the child’s birth and ending with their current residence. They were asked to identify their primary drinking water source at each residence, and any secondary sources they may have used. The field team collected water samples from all functioning tube-wells used at home and at school by participating children for at least 6 months during their lifetimes. Water samples were taken back to the Matlab Health Research Centre and stored at -20°C, and then sent to the icddr,b laboratory in Dhaka for analysis by hydride generation atomic absorption spectrophotometry analysis.21

For each child, for each year after birth, the field lab arsenic measurement results were weighted by the proportions of water used from each different water source. For tube-wells from which we could not obtain water samples, the arsenic concentrations measured in these wells during the 2002–03 survey of all tube-wells in Matlab were used. Some participants had at times used pond or river water for drinking. Because the arsenic concentrations were very low or non-detectable in initial pond/river test samples, we used zero as the concentration for all subsequent pond/river water sources. Arsenic exposure was classified in several ways. First, in utero arsenic exposure was assessed based on mother’s known exposure during the 9 months of pregnancy. Second, arsenic exposure during the first 5 years of life was calculated by taking the average water arsenic concentration during the first 5 years of life. Finally, peak arsenic exposure was defined as the highest known annual average arsenic concentration.

Health assessment

A detailed assessment of respiratory health was obtained, including questions regarding respiratory symptoms and disorders, upper and lower respiratory infections, pneumonia, asthma and wheezy disorders and tuberculosis. The 12-month prevalence of wheezing and asthma was assessed according to the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) core symptoms questions; cough and phlegm and breathlessness were assessed according to the ISAAC additional respiratory questions. The ISAAC questionnaire is recognized as a valid instrument for the assessment of prevalence and severity of childhood asthma symptoms throughout the world.22–24 Differently from the ISAAC procedure, which relies on a self-administered questionnaire, the questions were administered by a trained physician in a structured interview with the mothers of participating children.

Measurements of lung function were conducted for all study participants at the Matlab centre, as part of a physical examination. The field physician conducted an examination for current respiratory conditions, including acute respiratory illnesses that might affect lung function measurements, and spirometry was postponed if necessary. We used the EasyOne spirometer (NDD Medical Technologies, MA, USA), a hand-held, portable spirometer that uses ultrasound to measure airflow and is easy for children to use. The ultrasonic flow measurement is independent of gas composition, pressure, temperature and humidity, and eliminates errors due to those variables. This makes it particularly suitable for the hot and humid conditions in Matlab. Children were asked to perform at least three, and up to eight, maximal forced expiratory efforts in the standing position, without nose clips, to produce smooth, reproducible curves that meet American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria.25 The study physicians obtained A grades (per ATS criteria) for all but one of the children assessed, aged 7 to 17 years.

A household interview was conducted to assess socioeconomic status by several factors: parental education and occupation, the building material of their house, number of rooms and number of persons in the household.

Data analysis

We first performed univariate analyses to assess the children’s sociodemographic factors and other relevant basic characteristics and drinking water arsenic concentrations. We then conducted logistic regression analysis to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous respiratory symptoms, comparing children exposed to 10–499 µg/l and 500 µg/l and above to those children who had never been exposed in utero or at home and school to more than 10 µg/l. We first adjusted for age and gender, and then conducted further analyses adjusting for age, gender, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking and number of rooms in the house, which icddr,b has found to be a good indicator of socioeconomic status in this population. In view of clear unidirectional a priori hypotheses, one-sided P-values are presented for ORs. Incorporating water arsenic concentrations as a continuous variable identified the same symptoms with increased risks, so we present the findings with exposure stratified, which has the advantage of avoiding assumptions about the shape of exposure-response relationships. For those symptoms showing increases with arsenic concentrations in the first set of analyses, we further subdivided water concentrations into four categories (10–199 µg/l, 200–399 µg/l, 400–599 µg/l, 600+ µg/l) to further explore exposure-response relationships.

Multiple linear regression analyses were conducted using the spirometry parameters FEV1 and FVC, and the same exposure strata described above, and also with arsenic exposure inserted as a continuous variable. We first adjusted for age, gender and height. We tested for interaction of arsenic exposure with gender. In the absence of evidence of interaction by gender, we combined the data for boys and girls but included an indicator variable for gender. We then conducted further analyses, adjusting for age, gender, height, weight, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking status and number of rooms in the house.

Results

We identified 650 children (335 boys, 315 girls) aged 7–17 years in the subdistrict of Matlab, Bangladesh, selected from all children in the Matlab study region (n = 180 815) with pre-existing arsenic tube well concentration data from the 2002–03 survey. Characteristics of the study subjects are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the children (total n = 650)

| Total | Never exposed | 10-499 µg/l | 500+ µg/l | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | 335 (51.5) | 78 (49.1) | 109 (57.1) | 45 (48.9) |

| Girls | 315 (48.5) | 81 (50.9) | 82 (42.9) | 47 (51.1) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 7-9 | 222 (34.2) | 75 (47.2) | 68 (35.6) | 29 (31.5) |

| 10-12 | 222 (34.2) | 55 (34.6) | 63 (33.0) | 39 (42.4) |

| 13-15 | 149 (22.9) | 22 (13.8) | 43 (22.5) | 20 (21.7) |

| 16-17 | 57 (8.8) | 7 (4.4) | 17 (8.9) | 4 (4.4) |

| Grade (years) in school | ||||

| No grade | 66 (10.2) | 3 (1.9) | 18 (9.4) | 11 (12.0) |

| 1-3 | 269 (41.4) | 93 (58.5) | 84 (44.0) | 35 (38.0) |

| 4-6 | 208 (32.0) | 42 (26.4) | 66 (34.6) | 37 (40.2) |

| 7-9 | 93 (14.3) | 18 (11.3) | 19 (9.9) | 8 (8.7) |

| 10-11 | 14 (2.2) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Number of family members | ||||

| 2-4 | 193 (29.7) | 52 (32.7) | 59 (30.9) | 29 (31.5) |

| 5-6 | 312 (48.0) | 79 (49.7) | 93 (48.7) | 43 (46.7) |

| 7-8 | 103 (15.9) | 21 (13.2) | 29 (15.2) | 15 (16.3) |

| 9+ | 42 (6.5) | 7 (4.4) | 10 (5.2) | 5 (5.4) |

| Mother’s education | ||||

| No education | 206 (31.7) | 43 (27.0) | 63 (33.0) | 31 (33.7) |

| Primary | 292 (44.9) | 62 (39.0) | 93 (48.7) | 46 (50.0) |

| Secondary and above | 152 (23.4) | 54 (34.0) | 35 (18.3) | 15 (16.3) |

| Father’s education | ||||

| No education | 228 (35.1) | 61 (38.4) | 64 (33.5) | 35 (38.0) |

| Primary | 236 (36.3) | 39 (24.5) | 85 (44.5) | 39 (42.4) |

| Secondary and above | 186 (28.6) | 59 (37.1) | 42 (22.0) | 18 (19.6) |

| Type of house | ||||

| Mud | 579 (89.1) | 136 (85.5) | 174 (91.1) | 86 (93.5) |

| Mixed | 32 (4.9) | 11 (6.9) | 3 (1.6) | 5 (5.4) |

| Tin | 31 (4.8) | 9 (5.7) | 13 (6.8) | 1 (1.1) |

| Concrete | 8 (1.2) | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (–) |

| Rooms in the house | ||||

| 1 | 53 (8.2) | 12 (7.5) | 15 (7.8) | 8 (8.7) |

| 2 | 255 (39.2) | 76 (47.8) | 63 (33.0) | 41 (44.6) |

| 3 | 245 (37.7) | 48 (30.2) | 88 (46.1) | 27 (29.3) |

| 4+ | 97 (14.9) | 23 (14.5) | 25 (13.1) | 16 (17.4) |

| Mother smokes | ||||

| Yes | 32 (4.9) | 6 (3.8) | 9 (4.7) | 5 (5.4) |

| No | 618 (95.1) | 153 (96.2) | 182 (95.3) | 87 (94.6) |

| Father smokes | ||||

| Yes | 491 (75.5) | 115 (72.3) | 145 (75.9) | 72 (78.3) |

| No | 159 (24.5) | 44 (26.7) | 46 (24.1) | 20 (21.7) |

Exposure histories

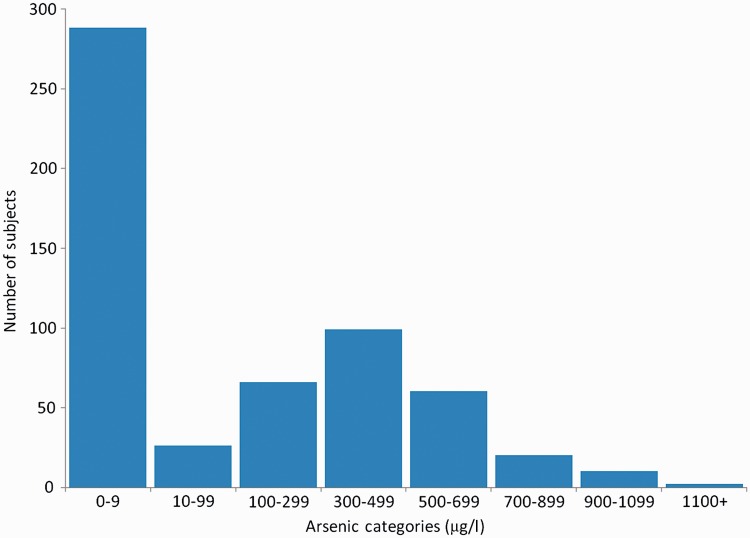

We obtained complete exposure histories at home for 524 (81%) children for the time since birth, for 571 (88%) children during pregnancy and for 551 children (85%) during the first 5 years of life. We also obtained complete exposure histories at school for 495 (85%) children out of 584 children who had been in school. Data on arsenic exposure are presented in Table 2. The average in utero arsenic concentration for exposed (>10 ug/l) children was 436.8 µg/l, with a maximum of 1512 µg/l. The average arsenic concentration during the first 5 years of life among exposed children was 383.2 ug/l, with a maximum of 996 µg/l (Table 2). Exposures in utero and in the first 5 years of life were highly correlated (with a correlation coefficient of 0.91) because when the child started drinking water, it was often from the same tube-wells the mother used during pregnancy; we were therefore unable to separate the effects of in utero exposure from the effects of early childhood exposure. The distribution of in utero exposures is given in Figure 1. As we had planned, about half the children had very low exposure in utero. The other half had a range of arsenic water concentrations, with the largest number falling in the range of 300–499 µg/l.

Table 2.

Exposure measures for only those children exposed to arsenic in drinking water

| Arsenic exposure measurea | Mean | Range | 25% Quantile | Median | 75% Quantile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In utero (n = 283) | 436.8 | 11.9–1512 | 232.2 | 467.0 | 620.4 |

| First 5 years of life (n = 270) | 383.2 | 11.3–996 | 212.1 | 388.0 | 506.0 |

| Home peak lifetime (n = 268) | 418.7 | 10.1–1512 | 218.0 | 242.2 | 596.5 |

| School peak lifetime (n = 196) | 246.0 | 10.0–899 | 45.7 | 204.0 | 363.8 |

aExcludes those subjects with unknown drinking water arsenic concentration for any year.

Figure 1.

Distribution of in utero drinking water arsenic exposure in study participants

Respiratory symptoms and lung function

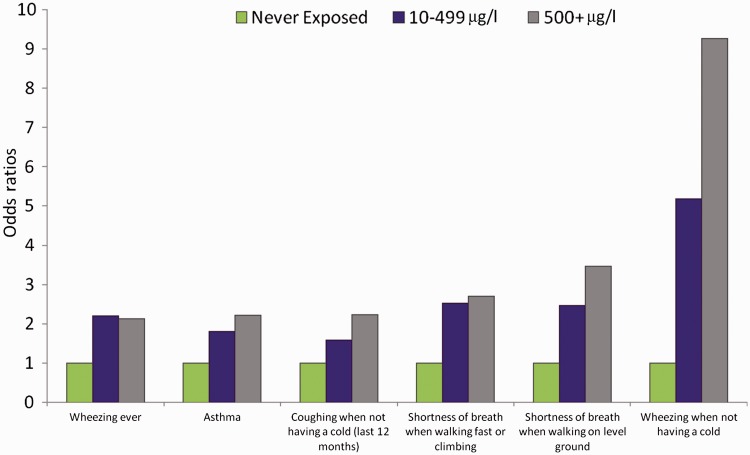

The prevalence ORs for respiratory symptoms following in utero exposure are presented in Table 3, with adjustment of age and gender in the left columns, and adjustment for age, gender, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking status and rooms in the house in the rightmost columns. Adjustment for the additional potential confounding factors made little difference, so we focus here on the results adjusted for age and gender. The strongest findings were for wheezing when not having a cold (in utero arsenic 10–499 µg/l, OR = 4.32, 95% CI: 0.91–20.5, 500 µg/L and above OR = 8.41, 95% CI: 1.66–42.6). The ORs for asthma were increased, with an OR of 2.33 (95% CI: 1.19–4.57) for the highest exposure category. Reporting shortness of breath when walking fast or climbing and when walking on level ground were also positively associated with arsenic exposure, with ORs of 3.19 (95% CI: 1.22–8.32) and 3.86 (95% CI: 1.09–13.7) respectively for the highest exposure category. Dose-response trends are presented in Figure 2 for all symptoms which reached an OR greater than 2 and P < 0.05 in the highest exposure category. When we analysed the data for exposure during the first 5 years of life, we obtained virtually the same results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Results from multivariate logistic regression analysis of respiratory symptoms and arsenic exposure in utero (10-499 µg/l and 500+ µg/l compared with never exposed)

| Age- and gender-adjusted |

More variables adjusteda |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory symptoms | 10-499 µg/l OR (95% CI) | P-valueb | 500+ µg/l OR (95% CI) | P-valueb | 10-499 µg/l OR (95% CI) | P-valueb | 500+ µg/l OR (95% CI) | P-valueb |

| Coughing | ||||||||

| When having a cold (last 12 months) | 1.71 (0.87–3.35) | 0.06 | 1.87 (0.80–4.37) | 007 | 1.81 (0.88–3.72) | 0.05 | 1.76 (0.73–4.27) | 0.10 |

| When not having a cold (last 12 months) | 1.80 (0.88–3.70) | 0.05 | 2.53 (1.12–5.69) | 0.01 | 1.58 (0.75–3.35) | 0.12 | 2.23 (0.96–5.16) | 0.03 |

| Dry cough (last 12 months) | 1.09 (0.71–1.69) | 0.35 | 0.87 (0.51–1.48) | 0.70 | 1.03 (0.65–1.64) | 0.44 | 0.77 (0.44–1.34) | 0.82 |

| Wheezing | ||||||||

| Ever | 2.14 (1.36–3.36) | <0.001 | 2.17 (1.26–3.75) | <0.01 | 2.20 (1.37–3.55) | <0.001 | 2.13 (1.21–3.73) | <0.01 |

| Last 12 months | 1.31 (0.69–2.47) | 0.20 | 1.46 (0.68–3.12) | 0.17 | 1.20 (0.61–2.35) | 0.30 | 1.23 (0.56–2.69) | 0.31 |

| Number of wheezing attacks (1- 3 times vs none) | 0.90 (0.43–1.89) | 0.61 | 1.18 (0.50–2.78) | 0.35 | 0.83 (0.38–1.80) | 0.68 | 1.03 (0.43–2.48) | 0.47 |

| Number of wheezing attacks (4+ times vs none) | 3.12 (0.97–10.0) | 0.03 | 2.80 (0.72–11.0) | 0.07 | 3.29 (0.94–11.5) | 0.03 | 2.60 (0.62–10.8) | 0.10 |

| Number of nights sleep being disturbed (<1 per week vs none) | 1.20 (0.57–2.50) | 0.31 | 1.80 (0.80–4.06) | 0.08 | 1.13 (0.52–2.45) | 0.38 | 1.55 (0.67–3.59) | 0.15 |

| Number of nights sleep being disturbed (1+ per week vs none) | 1.39 (0.44–4.40) | 0.29 | 0.74 (0.14–3.92) | 0.64 | 1.50 (0.44–5.15) | 0.26 | 0.71 (0.13–3.89) | 0.65 |

| Severe enough to affect speech | 1.84 (0.90–3.75) | 0.05 | 2.12 (0.92–4.88) | 0.04 | 1.68 (0.79–3.57) | 0.09 | 1.80 (0.76–4.26) | 0.09 |

| When after exercising | 1.58 (0.72–3.47) | 0.13 | 1.91 (0.76–4.79) | 0.08 | 1.36 (0.60–3.10) | 0.23 | 1.53 (0.59–3.95) | 0.19 |

| When not exercising | 1.52 (0.48–4.75) | 0.24 | 0.32 (0.04–2.83) | 0.85 | 1.59 (0.48–5.25) | 0.22 | 0.30 (0.03–2.80) | 0.85 |

| When having a cold | 1.39 (0.73–2.65) | 0.16 | 1.68 (0.79–3.57) | 0.09 | 1.31 (0.67–2.59) | 0.22 | 1.47 (0.67–3.21) | 0.17 |

| When not having a cold | 4.32 (0.91–20.5) | 0.03 | 8.41 (1.66–42.6) | <0.01 | 5.19 (1.04–25.9) | 0.02 | 9.26 (1.71–50.1) | <0.01 |

| Shortness of breath | ||||||||

| Woken up with shortness of breath | 1.57 (0.99–2.49) | 0.03 | 1.56 (0.90–2.72) | 0.06 | 1.60 (0.99–2.59) | 0.03 | 1.54 (0.87–2.73) | 0.07 |

| Woken up with tightness of chest | 1.35 (0.67–2.70) | 0.20 | 1.81 (0.83–3.96) | 0.07 | 1.22 (0.59–2.50) | 0.29 | 1.65 (0.74–3.67) | 0.11 |

| When walking fast or climbing | 2.74 (1.18–6.37) | <0.01 | 3.19 (1.22–8.32) | <0.01 | 2.53 (1.05–6.09) | 0.02 | 2.70 (1.01–7.20) | 0.02 |

| When walking on level ground | 2.30 (0.70–7.58) | 0.09 | 3.86 (1.09–13.7) | 0.02 | 2.46 (0.70–8.67) | 0.08 | 3.46 (0.94–12.7) | 0.03 |

| Stops for breath when walking at own pace on level ground | 1.91 (0.63–5.76) | 0.13 | 1.34 (0.33–5.40) | 0.34 | 2.28 (0.69–7.57) | 0.09 | 1.21 (0.27–5.31) | 0.40 |

| Asthma | 1.84 (1.04–3.26) | 0.02 | 2.33 (1.19–4.57) | <0.01 | 1.80 (0.99–3.28) | 0.03 | 2.21 (1.11–4.38) | 0.01 |

| Pneumonia | 2.11 (1.30–3.43) | <0.01 | 1.43 (0.79–2.61) | 0.12 | 2.20 (1.32–3.66) | <0.01 | 1.43 (0.78–2.65) | 0.13 |

aAdjusted for age, gender, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking status and rooms in the house.

bOne-sided.

Figure 2.

Odds ratios for respiratory symptoms which exceeded 2.0, with P < 0.05, in the highest exposure category. Adjusted for age, gender, mother's education, father's education, father's smoking status and rooms in the house

In Table 4, the age- and gender-adjusted ORs for the same six respiratory symptoms shown in Figure 2 are presented according to four strata of arsenic exposure, from 10–199 µg/l to >600 µg/l. Although estimates in individual strata are unstable due to small numbers, there were overall increases in symptoms with increasing exposure (trend test P-values < 0.01 for five symptoms, and P = 0.03 for coughing when not having a cold.)

Table 4.

Age- and gender-adjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs for six respiratory symptoms according to four categories of in utero arsenic exposure, with those who were never exposed in utero and throughout childhood up to the present as the referent group

| 10-199 µg/l | 200-399 µg/l | 400-599 µg/l | 600+ µg/l | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory symptoms | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P-trenda |

| Wheezing ever | 1.98 (1.03–3.80) | 1.51 (0.83–2.74) | 3.17 (1.78–5.64) | 2.12 (1.19–3.76) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 1.23 (0.50–3.02) | 1.88 (0.90–3.92) | 2.26 (1.13–4.49) | 2.38 (1.17–4.83) | <0.01 |

| Coughing when not having a cold (last 12 months) | 2.37 (0.92–6.09) | 1.62 (0.64–4.11) | 1.78 (0.74–4.31) | 2.47 (1.05–5.79) | 0.03 |

| Shortness of breath when walking fast or climbing | 1.07 (0.27–4.28) | 2.89 (1.06–7.91) | 4.09 (1.56–10.7) | 3.20 (1.18–8.71) | <0.01 |

| Shortness of breath when walking on level ground | 1.30 (0.72–7.58) | 2.21 (0.54–9.12) | 4.50 (1.17–17.3) | 3.37 (0.88–12.8) | 0.01 |

| Wheezing when not having a cold | 5.01 (0.78–32.0) | 1.57 (0.20–12.1) | 8.65 (1.64–45.7) | 8.21 (1.56–43.1) | <0.01 |

aOne-sided.

Table 5 presents multiple linear regression analysis findings concerning lung function. There was no evidence of interaction by gender (P-values > 0.2) so results are presented for boys and girls combined, but with gender incorporated into the analysis. This table provides the differences in FEV1 and FVC between the exposed groups (10–499 and ≥500 µg/l) and the unexposed group (<10 µg/l), and also the results when treating arsenic exposure as a continuous variable. Overall, the lung function results associated with exposure to arsenic are very close to those for unexposed children. Children in the highest exposure category of >500 µg/l in utero had a mean FEV1 22.6 ml lower than children never exposed to more than 10 µg/l, but the CIs were wide (−72.7 ml – +27.6 ml) and the one-sided P-value was 0.19. The results concerning FVC were similar, as were the results when we treated arsenic in utero as a continuous variable shown in the right column of Table 5. Adjustment for weight, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking status and rooms in house had only small effects on the findings.

Table 5.

Results from multivariate linear regression analysisa of lung function and arsenic exposure in utero (10-499 µg/l and 500+ µg/l compared with never exposed, and also with arsenic as a continuous variable)

| Age-, gender- and height-adjusted |

More variables adjusteda |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung function | 10-499 µg/l (95% CI) | P-valueb | 500+ µg/l (95% CI) | P-valueb | 10-499 µg/l (95% CI) | P-valueb | 500+ µg/l (95% CI) | P-valueb | Continuous (95% CI) | P-valueb |

| FEV1 (ml) | 19.1 (−22.5 to +60.7) | 0.82 | −22.4 (−7.32 to +28.4) | 0.19 | 16.4 (−25.5 to +58.3) | 0.78 | −22.6 (−72.7 to +27.6) | 0.19 | −0.013 (−0.076 to + 0.049) | 0.34 |

| FVC (ml) | 28.9 (−16.5 to +74.2) | 0.89 | −17.4 (−72.9 to +38.1) | 0.27 | 27.0 (−18.5 to +72.5) | 0.88 | −17.2 (−71.6 to +37.3) | 0.27 | −0.007 (−0.075 to + 0.061) | 0.43 |

aAdjusted for age, gender, height, weight, mother’s education, father’s education, father’s smoking status and rooms in the house.

bOne-sided.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first cohort study of pulmonary health effects in children after early life exposure to arsenic, including exposure in utero, and the first study to use a standardized structured respiratory questionnaire. We found strong associations between early life exposure to high amounts of arsenic in drinking water and various respiratory endpoints. For exposures in utero above 500 µg/l, there were increases in wheezing when not having a cold (OR = 8.41, 95% CI: 1.66–42.6), shortness of breath when walking fast or climbing (OR = 3.19, 95% CI: 1.22–8.32) and when walking on level ground (OR = 3.86, 95% CI: 1.09–13.7). The only previous findings in children were from Antofagasta in Chile, where cross-sectional studies suggested that pronounced increases in respiratory symptoms were associated with water arsenic exposure.9

We had expected to find reduced lung function in our study children because in adults we had previously found reduced lung function associated with arsenic skin lesions12 and our pilot study in Chile found preliminary evidence of reduced lung function among adults aged 30–65 years, observed decades after early life exposure.3 However, it may be that reductions in lung function parameters will occur later, with respiratory symptoms being the first manifestation of early life exposure effects on the lungs. In light of reduced lung function in adults, including adults studied decades after early life exposure, we plan to follow these children in Bangladesh prospectively to see if they develop reductions in lung function and other effects as they grow older.

One strength of our study is the wide range of exposures to arsenic, including a referent group never known to have been exposed to more than 10 µg/l of arsenic in water in utero or during childhood. Although exposure assessment is always incomplete in rural populations like this with many potential drinking water sources, the large contrasts in concentrations between subjects exposed to above 500 µg/l and those exposed to less than 10 µg/l strengthen the overall evidence of arsenic effects.

Furthermore, we collected data on major potential confounding factors, and adjusted for them when appropriate. Socioeconomic status was adjusted for using mother’s education, father’s education and number of rooms in the house. These adjustments had little effect on the results (Tables 3–5). Adjusting for cooking locations (indoor, outdoor) and fuels used for cooking (firewood, straw, dung) also had little effect. For example, the ORs for associations between early life exposure to high amounts of arsenic in drinking water and wheezing when not having a cold, or shortness of breath when walking fast or climbing, changed from 8.41 to 8.97 and 3.19 to 3.18, respectively, when we adjusted for cooking location, and to 7.41 and 3.07, respectively, when we adjusted for firewood use.

A weakness of this study is that we could not parse in utero exposures from exposures during the first 5 years of life, but this difficulty is probably universal to in utero and early childhood drinking water studies. Children exposed to high levels of arsenic are most likely drinking from the same sources as their mothers were when pregnant with them.

Though the lung may seem a surprising target for an ingested substance, ample evidence has shown that this is indeed the case for arsenic. The exact mechanisms by which arsenic causes lung disease are unknown, and further research is needed. However, the biological plausibility that ingested arsenic can cause toxicity to the lungs is supported by a variety of studies. Arsenic has been found to accumulate in the lungs in animal studies more than in most other organs except for the kidney and liver.26-29 In humans, arsenic in water is a well-established cause of lung cancer,30 and lung cancer is perhaps the main cause of long-term mortality from drinking arsenic-contaminated water.31 Furthermore, the pathway of exposure does not appear to impact on lung effects since lung cancer risks appear to be related to the absorbed dose of arsenic, regardless of whether arsenic is ingested or inhaled.32 These various lines of evidence support the biological possibility of pulmonary effects from ingestion of inorganic arsenic.

In conclusion, we found marked increases in respiratory symptoms following arsenic exposure in utero and in early childhood. These findings, suggesting major impacts on the lungs following early life exposure, are consistent with the large increases in young adult mortality due to lung cancer and bronchiectasis we previously identified in Chile following early life exposure to arsenic in water.4,5 Further investigation of the in utero and early childhood effects of arsenic are needed, but we believe the current evidence is sufficient to give high priority to reducing the exposure of pregnant women and children in the many countries where high concentrations of arsenic are still found in water.

Acknowledgements

We thank Brenda Eskenazi for her advice and comments, and we acknowledge with gratitude the commitment of the National Institutes of Health to our research efforts.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants no.R01-HL081520 and P42-ES004705.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

KEY MESSAGES.

Little is known about the effect of exposure to arsenic in drinking water in utero and during early life.

We studied chronic respiratory disease in 650 children aged 7–17 years in Bangladesh. About half the children were never exposed to more than 10 µg/l of arsenic in utero and throughout childhood, whereas the other half had a range of arsenic exposures, including some above 500 µg/l.

Children who had experienced in utero exposure to more than 500 µg/l of arsenic were more than eight times more likely to report wheezing when not having a cold, and more than three times more likely to report shortness of breath when walking on level ground and when walking fast or climbing.

Our findings suggest that in utero and early life exposure to arsenic leads to chronic respiratory symptoms in children. However, we were not able to distinguish whether the effects resulted from in utero exposure, exposure in the first years after birth, or both.

References

- 1.Etzel RA, Balk SJ, editors. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Environmental Health. 2nd edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Children’s Health and Environment: a Review of Evidence. Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dauphine DC, Ferreccio C, Guntur S, et al. Lung function in adults following in utero and childhood exposure to arsenic in drinking water: preliminary findings. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;84:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s00420-010-0591-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AH, Marshall G, Yuan Y, et al. Increased mortality from lung cancer and bronchiectasis in young adults after exposure to arsenic in utero and in early childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1293–96. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AH, Marshall G, Liaw J, Yuan Y, Ferreccio C, Steinmaus C. Mortality in Young Adults Following in Utero and Childhood Exposure to Arsenic in Drinking Water. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;114:1293–96. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgono JM, Vicent P, Venturino H, Infante A. Arsenic in the drinking water of the city of Antofagasta: epidemiological and clinical study before and after the installation of a treatment plant. Environ Health Perspect. 1977;19:103–05. doi: 10.1289/ehp.19-1637404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borgono JM, Greiber R. [Epidemiologic study of arsenic poisoning in the city of Antofagasta] Rev Med Chil. 1971;99:702–07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zaldivar R. Arsenic contamination of drinking water and foodstuffs causing endemic chronic poisoning. Beitr Pathol. 1974;151:384–400. doi: 10.1016/s0005-8165(74)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaldivar R, Ghai GL. Clinical epidemiological studies on endemic chronic arsenic poisoning in children and adults, including observations on children with high- and low-intake of dietary arsenic. Zentralbl Bakteriol [B] 1980;170:409–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guha Mazumder DN, Haque R, Ghosh N, et al. Arsenic in drinking water and the prevalence of respiratory effects in West Bengal, India. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:1047–52. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milton AH, Hasan Z, Rahman A, Rahman M. Chronic arsenic poisoning and respiratory effects in Bangladesh. J Occup Health. 2001;43:136–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Ehrenstein OS, Mazumder DN, Yuan Y, et al. Decrements in lung function related to arsenic in drinking water in West Bengal, India. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:533–41. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guha Mazumder DN, Steinmaus C, Bhattacharya P, et al. Bronchiectasis in persons with skin lesions resulting from arsenic in drinking water. Epidemiology. 2005;16:760–65. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000181637.10978.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvez F, Chen Y, Brandt-Rauf PW, et al. A prospective study of respiratory symptoms associated with chronic arsenic exposure in Bangladesh: findings from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study (HEALS) Thorax. 2010;65:528–33. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.119347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nafees AA, Kazi A, Fatmi Z, Irfan M, Ali A, Kayama F. Lung function decrement with arsenic exposure to drinking groundwater along River Indus: a comparative cross-sectional study. Environ Geochem Health. 2011;33:203–16. doi: 10.1007/s10653-010-9333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parvez F, Chen Y, Brandt-Rauf PW, et al. Nonmalignant respiratory effects of chronic arsenic exposure from drinking water among never-smokers in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:190–05. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chattopadhyay BP, Mukherjee AK, Gangopadhyay PK, Alam J, Roychowdhury A. Respiratory effect related to exposure of different concentrations of arsenic in drinking water in West Bengal, India. J Environ Sci Eng. 2010;52:147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amster ED, Cho JI, Christiani D. Urine arsenic concentration and obstructive pulmonary disease in the U.S. population. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2011;74:716–27. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.556060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pesola GR, Parvez F, Chen Y, Ahmed A, Hasan R, Ahsan H. Arsenic exposure from drinking water and dyspnoea risk in Araihazar, Bangladesh: a population-based study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1076–83. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00042611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman A, Vahter M, Ekstrom EC, Persson LA. Arsenic exposure in pregnancy increases the risk of lower respiratory tract infection and diarrhea during infancy in Bangladesh. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:719–24. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahed MA, Chowdhury D, Nermell B, et al. A modified routine analysis of arsenic content in drinking-water in Bangladesh by hydride generation-atomic absorption spectrophotometry. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;24:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Steering Committee. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Eur Respir J. 1998;12:315–35. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaw R, Woodman K, Ayson M, et al. Measuring the prevalence of bronchial hyper-responsiveness in children. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:597–602. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson PG, Henry R, Shah S, et al. Validation of the ISAAC video questionnaire (AVQ3.0) in adolescents from a mixed ethnic background. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1181–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–36. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertolero F, Marafante E, Rade JE, Pietra R, Sabbioni E. Biotransformation and intracellular binding of arsenic in tissues of rabbits after intraperitoneal administration of 74As labelled arsenite. Toxicology. 1981;20:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(81)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marafante E, Rade JE, Sabbioni E, Bertolero F, Foa V. Intracellular interaction and metabolic fate of arsenite in the rabbit. Clin Toxicol. 1981;18:1335–41. doi: 10.3109/00099308109035074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenyon EM, Hughes MF, Adair BM, et al. Tissue distribution and urinary excretion of inorganic arsenic and its methylated metabolites in C57BL6 mice following subchronic exposure to arsenate in drinking water. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vahter M, Marafante E, Dencker L. Tissue distribution and retention of 74As-dimethylarsinic acid in mice and rats. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1984;13:259–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01055275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Some Drinking-Water Disinfectants and Contaminants, Including Arsenic. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan Y, Marshall G, Ferreccio C, et al. Acute myocardial infarction mortality in comparison with lung and bladder cancer mortality in arsenic-exposed region II of Chile from 1950 to 2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1381–91. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith AH, Ercumen A, Yuan Y, Steinmaus CM. Increased lung cancer risks are similar whether arsenic is ingested or inhaled. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:343–48. doi: 10.1038/jes.2008.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]