Abstract

The effects of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR signaling pathways on cell cycle progression, gene expression, prevention of apoptosis and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs were examined in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells which are conditionally-transformed to grow in response to Raf-1 and Akt-1 activation by treatment with testosterone or tamoxifen respectively. In these cells we can compare the effects of normal cytokine vs. oncogene mediated signaling in the same cells by changing the culture conditions. Raf-1 was more effective than Akt-1 in inducing cell cycle progression and preventing apoptosis in the presence and absence of chemotherapeutic drugs. The normal cytokine for these cells, interleukin-3 induced/activated most downstream genes transiently, with the exception of p70S6K that was induced for prolonged periods of time. In contrast, most of the downstream genes induced by either the activate Raf-1 or Akt-1 oncogenes were induced for prolonged periods of time, documenting the differences between cytokine and oncogene mediated gene induction which has important therapeutic consequences. The FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were sensitive to MEK and PI3K/mTOR inhibitors. Combining MEK and PI3K/mTOR inhibitors increased the induction of apoptosis. The effects of doxorubicin on the induction of apoptosis could be enhanced with MEK, PI3K and mTOR inhibitors. Targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways may be an effective approach for therapeutic intervention in those cancers which have upstream mutations which result in activation of these pathways.

Keywords: Raf, Akt, signal transduction inhibitors, cell cycle progression, chemotherapeutic drugs, drug resistance

Introduction

Proliferation and suppression of apoptosis in many hematopoietic precursor cells is promoted by interleukin-3 (IL-3) and other cytokines/growth factors.1-4 Hematopoietic cell lines have been isolated which require IL-3 for proliferation and survival.5 The FL5.12 cell line is an IL3-dependent cell line isolated from murine fetal liver and is an in vitro model of early hematopoietic progenitor cells.4,5 Cytokine-deprivation of these cells results in rapid cessation of growth with subsequent death by apoptosis (programmed cell death).6-9 In the presence of IL-3, these cells proliferate continuously, however, they are non-tumorigenic upon injection into immunocompromised mice.6-9 Spontaneous factor-independent cells are rarely recovered from FL5.12 cells (< 10−7), making it an attractive model to analyze the effects various genes have on signal transduction, cell cycle progression, leukemogenesis and drug resistance.6-10 These results indicate the key roles that cytokines can exert in controlling cell cycle progression and disruption of these regulatory loops can contribute to malignant transformation.

IL-3 exerts its biological activity by binding the IL-3 receptor (IL-3R) which activates the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and other signaling and anti-apoptotic cascades.1,2 Aberrant expression of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways have been detected in many leukemia samples and their joint overexpression can be associated with a worse prognosis.11 These signaling cascades may be activated by aberrant expression of upstream cytokine receptors or by mutations in intrinsic components in various cancers and contribute to drug resistance.10-23

Relatively little is known regarding the interactions between the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways in terms of cell cycle progression, prevention of apoptosis and sensitivity to classical chemotherapy.19-23 However, it is becoming increasing more apparent that both of these pathways are often simultaneously dysregulated in many cancers.1,2,11 Understanding the roles the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR cascades play in the control of cell cycle progression will enhance our knowledge of how these pathways regulate the sensitivity of cancer cells to various therapeutic approaches. In the following studies, we sought to determine the effects of Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways on cell cycle progression, prevention of apoptosis and gene expression. In order to investigate potential roles, we transformed IL3-dependent FL5.12 cells to proliferate in response to activation of Raf-1 and Akt-1 in the absence of exogenous cytokines.24 In our conditionally-inducible model, we can investigate the individual contributions these pathways exert on cell cycle progression and gene expression. Furthermore we can compare the effects of normal cytokine vs. activated oncogene signaling on cell cycle progression, gene expression, apoptosis and sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drug in the same cell, avoiding the complicated complexities of different genetic backgrounds and differentiation states that are often encountered upon comparison of different tumors, even of the same cell lineage.

Results

Effects of Raf-1 and Akt-1 activation on cell cycle progression in conditionally-transformed FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells

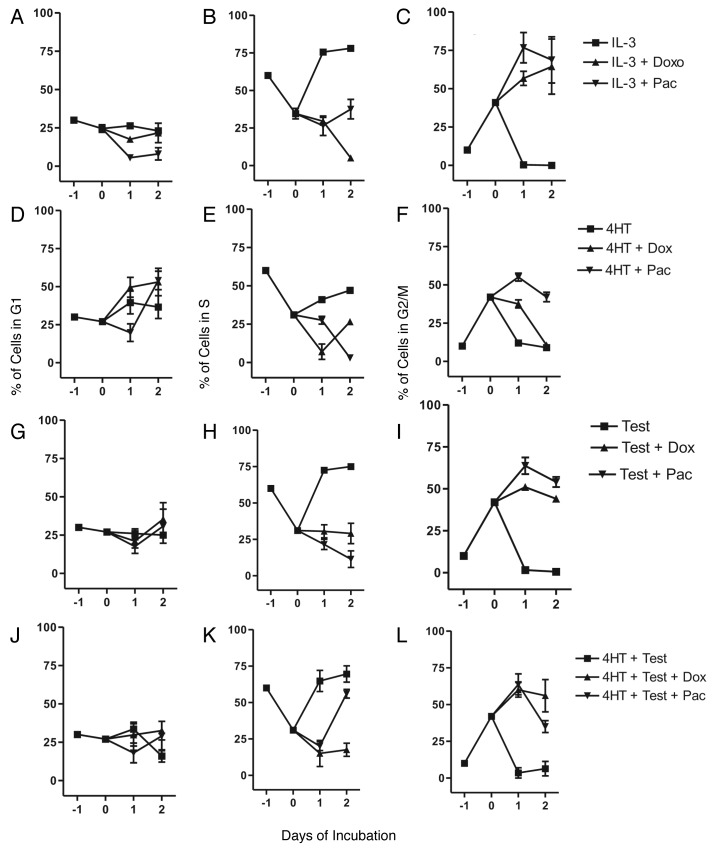

The effects of Raf-1 and Akt-1 on cell cycle progression were examined in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells which proliferate in response to activation of Raf-1 and Akt-1 in the absence of exogenous IL-3 (Fig. 1). At the start of these experiments (T-1 point), approximately 30% of FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were in G1 (A), 60% in S (B) and 10% in G2/M (C). After 4HT + Test deprivation of FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells for 24 h (T0 point), 25% of the cells were in the G1 phase (A), 35% were in S phase (B) and 41% were in G2/M (C). These results indicated that removal of 4HT + Test evoked exit from S phase and entry into G2/M phase.

Figure 1. Dominance of Raf-1 on cell cycle progression in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells in the presence of chemotherapeutic drugs. Cells were collected 1 d prior to the start of these experiments (Day -1), washed with PBS and then resuspended in medium with 5% FBS lacking IL-3, 4HT, Test or 4HT + Test. At Day 0, IL-3, 4HT, Test or 4HT + Test in the presence and absence of 100 nM doxorubicin or 10 nM paclitaxel were added. One ml aliquots were removed from each culture every 24 h and the extent of cell cycle progression determined by flow cytometric analysis after propidium iodine staining as described.25-27 Symbols: solid squares (■) = IL-3 [10% WEHI-3B conditioned medium supernatant (WCM)], 500 nM 4HT, 100 nM Test, or 500 nM 4HT + 100 nM Test in the absence of chemotherapeutic drugs, solid upward triangles (▲) = IL-3 (10% WCM), 500 nM 4HT, 100 nM Test, or 500 nM 4HT + 100 nM Test in the presence of 100 nM doxorubicin, solid downward triangles (▼) = IL-3 (10% WCM), 500 nM 4HT, 100 nM Test, or 500 nM 4HT + 100 nM Test in the presence of 10 nM paclitaxel. These experiments were performed three times and averaged together.

As a control, these cells were treated with IL-3 which induced entry into S phase (B) and exit from G2/M phase (C). When these cells were treated with 4HT, which activated ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+), there were some increases in the percentage of cells which entered the S phase of the cell cycle from 35 to 41 and 47% after 1 and 2 d respectively (E). In contrast, when the cells were treated with Test which activated ΔRaf-1:AR, approximately 75% of the cells were in the S phase after 1 d (H). Addition of 4HT + Test which activated both ΔAkt-1-ER* and ΔRaf-1:AR respectively, also induced entry into S phase (K) and exit from G2/M. Interestingly, the combination of 4HT + Test promoted slightly less entry in the S phase than Test treatment alone (Compare K and H). In summary, activation of Raf-1 resulted in entry of the cells into S phase. Activation of Akt-1 by itself, did not result in as many cells in S phase as after activation of Raf-1 (compare E and H) and actually may inhibit the effects of Raf activation on entry into S phase. Addition of Test (I) or 4HT (F) also resulted in a decrease in the percentage of cells in G2/M.

The effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and paclitaxel on cell cycle progression were examined. When the cells were treated with IL-3 and either doxorubicin or paclitaxel, blocks in G2/M were observed (C). When the FL/ΔAkt:

ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were cultured with 4HT and either doxorubicin or paclitaxel, doxorubicin induced primarily a block in G1 (D) while paclitaxel mediated primarily a block in G2/M (F). Although in both cases, some cells were blocked in both phases of the cell cycle.

When the FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were treated with Test and either doxorubicin or paclitaxel, approximately 25 and 30% of the cells were in the G1 phase after 2 d of treatment respectively (G). Approximately 18 and 25% of the cells were in S phase (H) and 50% of the cells were in the G2/M phase when the cells were treated with Test and either doxorubicin or paclitaxel for 2 d respectively (I). Thus treatment with Test, which activated Raf-1, and either doxorubicin or paclitaxel resulted in a G2/M block. The combination of paclitaxel with 4HT + Test also resulted in a block in G2/M (L). However, after 2 d of treatment with 4HT + Test + paclitaxel (K), more cells registered in S phase than cells just treated with Test + paclitaxel (H) or 4HT + paclitaxel (E) demonstrating that activation of Raf-1 and Akt-1 in the presence of paclitaxel resulted in the cells remaining in S phase.

Conditional activation of the Raf-1 and Akt-1

In the following studies, we sought to determine the differences between cytokine mediated normal signaling and oncogene mediated signaling in a single conditionally-transformed cell line

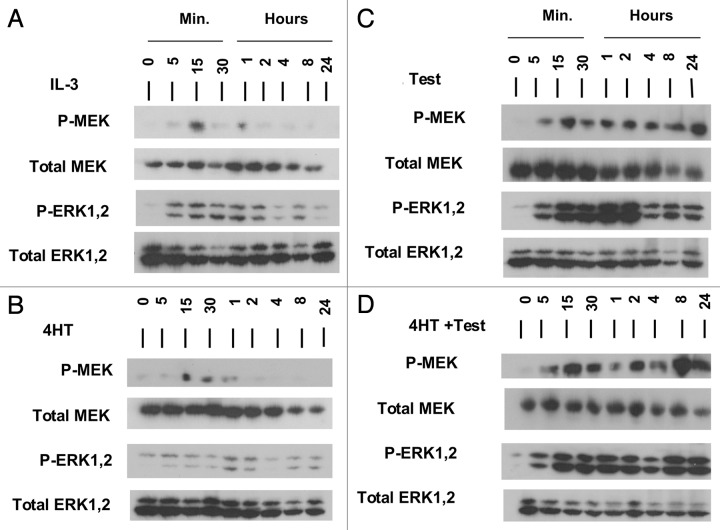

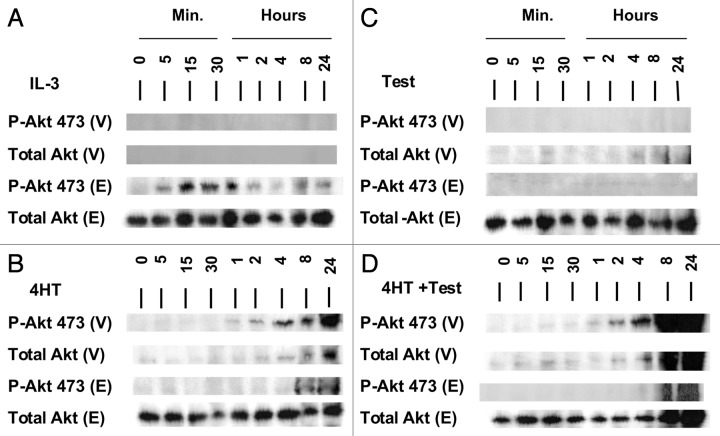

(Figs. 2 and 3). Upon deprivation of FL/ΔAkt-1:ER* + ΔRaf-1:AR cells of 4HT and Test for 24, the cells entered the G1 phase of the cell cycle and activated (phosphorylated, P) forms of MEK1, ERK1,2 and Akt were either not detected or observed at low levels (Figs. 2 and 3). Cells were then treated with IL-3, 4HT, Test, or the combination of 4HT + Test. IL-3 induced transiently MEK1 activation (5 min) and downstream ERK1,2 activation (5 min to 2 h) (A). The levels of total MEK1 and ERK1,2 remained relatively constant over these time courses. When these blots were probed with an antibody which recognized Akt, two bands were detected, the endogenous (E) Akt protein and the vector-derived (V) ΔAkt-1:ER protein (Fig. 3). The chimeric ΔAkt-1:ER*protein migrates at a higher molecular weight than the endogenous Akt as the chimeric ΔAkt-1:ER protein has the attached ER* domain.24 IL-3 induced the appearance of E- but not vector V-derived activated Akt-1 as early as 5 min of stimulation (Fig. 3A).

Figure 2. Conditional Activation of MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR Cells. FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in the presence of phenol red free RPMI 1640 containing 5% CS FBS (to avoid endogenous estrogen-like compounds) for 24 h. Cells were treated with IL-3 (10% WCM), 4HT (500 nM), Test (100 nM) or 4HT + Test (500 + 100 nM) for the indicated time intervals. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for phospho and total MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 and Akt (S473).

Figure 3. Conditional Activation of Akt-1 in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR Cells. FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in the presence of phenol red free RPMI 1640 containing 5% CS FBS (to avoid endogenous estrogen-like compounds) for 24 h. Cells were treated with IL-3 (10% WCM), 4HT (500 nM), Test (100 nM) or 4HT + Test (500 + 100 nM) for the indicated time intervals. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for phospho and total Akt (S473). (V) = vector derived ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) and (E) = endogenous Akt. Similar results were obtained with the phosphospecific Akt T308 Ab.

Upon stimulation of FL/ΔAkt-1:ER* + ΔRaf-1:AR cells by Test, there was a strong and prolonged activation of MEK1 and ERK1,2 (Fig. 2C). In contrast activation of ΔRaf-1:AR cells by Test did not result in Akt activation (Fig. 3C).

Treatment with either 4HT or 4HT + Test induced vector derived activated ΔAkt-1:ER* starting at 1 h and increased to maximal levels after 8–24 h (Fig. 3B and D). Stimulation of ΔAkt-1:ER* activity by 4HT treatment did not result in activation of either MEK1 or ERK1,2 (Fig. 2B). When both the Raf and Akt pathways were activated by 4HT + Test treatment, prolonged activation of MEK1 and ERK1,2 occurred (Fig. 2D).

Activation of downstream signal transduction cascades

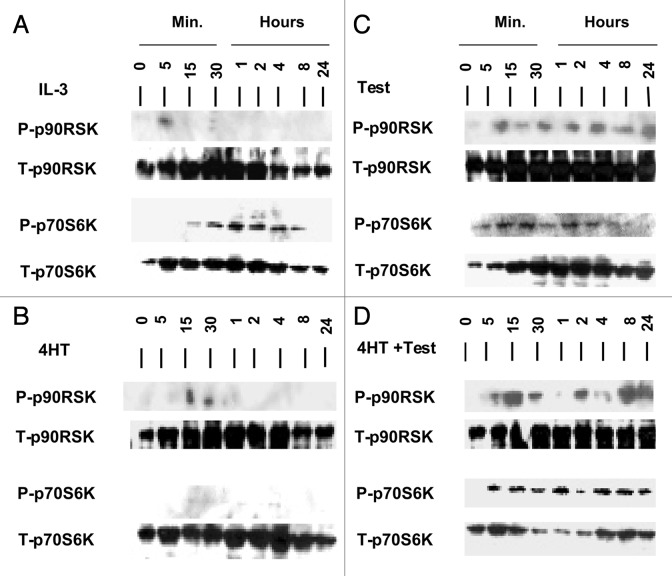

The effects of normal cytokine or oncogenic Raf-1 or Akt-1 activation on downstream signaling molecules in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER* + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were compared. IL-3 or Akt-1 induced transient activation of p90Rsk-1, while Raf-1 induced prolonged activation (Fig. 4A–C).

Figure 4. Conditional Activation of p90Rsk and p70S6K in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR Cells. FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in the presence of phenol red free RPMI 1640 containing 5% CS FBS (to avoid endogenous estrogen-like compounds) for 24 h. Cells were treated with IL-3 (10% WCM), 4HT (500 nM), Test (100 nM) or 4HT and Test (500 + 100 nM) for the indicated time intervals. Then western blots were performed and probed with antibodies specific for phospho and total p90Rsk and p70S6K.

A critically important downstream signaling molecule is p70S6K, whose expression is regulated by both the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways.1,2 Prolonged activation of p70S6K was detected after IL-3 treatment (Fig. 4A). In contrast, transient biphasic activation of p70S6K was observed after of Raf-1 (Fig. 4C) but was not seen after Akt-1 activation (Fig. 4B). However, prolonged p70S6K activation was detected when both Raf-1 and Akt-1 were activated (Fig. 4D). This was determined by probing the western blots with the phosphospecific T389 p70S6K Ab and indicated that in these cells, either IL-3 stimulation or Raf-1 and Akt-1 activity was required for prolonged p70S6K activation.

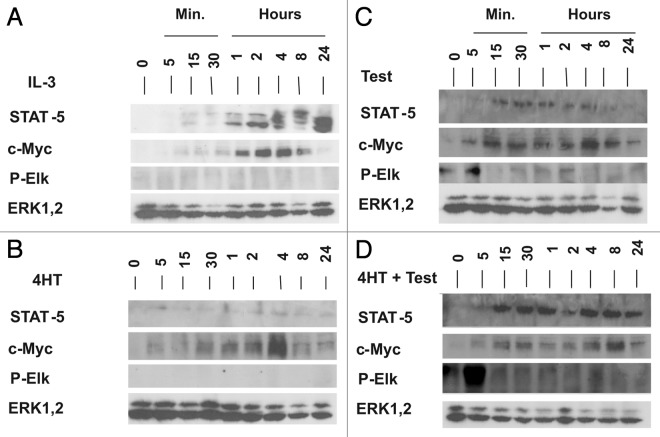

We examined the effects of activation of these pathways on transcription factors normally regulated by IL-3 (Fig. 5). IL-3 induced the expression of the STAT5 and c-Myc transcription factors (Fig. 5A). c-Myc was induced after Akt-1, Raf-1 or Raf-1 and Akt-1 stimulation (Fig. 5B–D). STAT5 was induced after Raf-1 or Raf-1 and Akt-1 activation but not after activation of Akt-1 by itself (Fig. 5B–D).

Figure 5. Conditional Activation of STAT5, c-Myc and ELK Transcription Factors in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR Cells. FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in the presence of phenol red free RPMI 1640 containing 5% CS FBS (to avoid endogenous estrogen-like compounds) for 24 h. Cells were treated with IL-3 (10% WCM), 4HT (500 nM), Test (100 nM) or 4HT and Test (500 + 100 nM) for the indicated time intervals. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for total STAT5, total c-Myc, phospho-Elk-1 and total ERK.

The expression of activated Elk was also examined in response to Raf-1 or Akt-1 activation. Neither IL-3 nor Akt-1 activation resulted in Elk activation (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast Raf-1 or Raf-1 plus Akt-1 activation resulted in the induction of activated Elk (Fig. 5C and D). Interestingly, Elk activation was not detected in these cells after IL-3 stimulation (Fig. 5A). Thus there are clear differences between cytokine- and oncogene-mediated gene activation in cells of the same genetic background. As a loading control, the expression of T-ERK is presented. This is the same panel with T-ERK as that presented in Figure 2. For internal consistency, the results obtained in Figures 2–4 were all obtained from the same protein samples run on two sets of gels and transferred to two sets of filters.

Dominance of Raf-1 on the prevention of apoptosis in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells

The effects of Raf-1 and Akt-1 activation on the prevention of apoptosis were determined in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells (Table 1). Raf-1 prevented apoptosis more efficiently than Akt-1 as approximately 15% of the cells were apoptotic when ΔRaf-1:AR was activated while 58% of the cells were apoptotic when only ΔAkt-1:ER* was activated.

Table 1. Effects of MEK, PI3K and mTOR inhibitors on the induction of apoptosis in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells.

| Treatment | +Raf-1 activation | +Akt-1 activation |

|---|---|---|

| None |

15% ± 2.1% (1X) |

58% ± 6.2% (1X) |

| 1 μM MEK inhibitor |

43% ± 5.2% (2.9X) |

71% ± 8.0% (1.2X) |

| 10 μM MEK inhibitor |

66% ± 6.9% (4.4X) |

83% ± 7.8% (1.4X) |

| 1 μM PI3K inhibitor |

15% ± 1.8% (1X) |

64% ± 7.1% (1.1X) |

| 10 μM PI3K inhibitor |

63% ± 7.2% (4.2X) |

91% ± 9.2% (1.6X) |

| 10 nM mTOR inhibitor |

41% ± 5.5% (2.7X) |

85% ± 9.3% (1.5X) |

| 100 nM mTOR inhibitor | 42% ± 7.9% (2.8X) | 87% ± 8.4% (1.5X) |

The effects Raf-1 and Akt activation in the presence of MEK, mTOR and PI3K inhibitors on the induction of apoptosis was measured by Annexin V/PI as described.24 A representative Annexin V/PI experiment is presented in Figure 6. These experiments were repeated 3 times and similar results were observed. The percentage of apoptotic cells is presented, followed by the fold increase in apoptosis (presented in parentheses) after either Raf-1 or Akt-1 stimulation respectively for three days. Fold increases in apoptosis are normalized to the levels of apoptosis observed after either Raf-1 or Akt-1 activation in the absence of any inhibitors.

The effects of inhibition of MEK, PI3K and mTOR were examined. When ΔRaf-1:AR was activated, the cells were sensitive to MEK and mTOR inhibitors and high concentrations of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM). Likewise when ΔAkt-1:ER* was activated, the cells were sensitive to the MEK, mTOR and high concentrations of the PI3K inhibitor. However, the effects of these inhibitors were less dramatic when only ΔAkt-1:ER was activated as 58% of the cells registered as apoptotic in the absence of these inhibitors (Table 1).

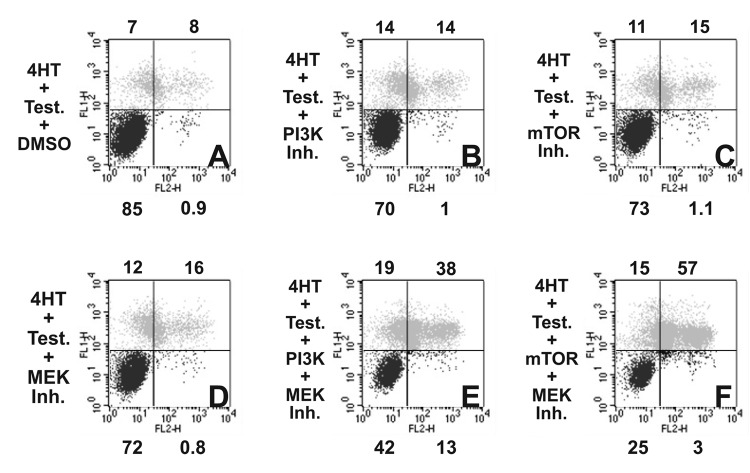

Combining MEK with mTOR or PI3K inhibitors increases apoptosis in FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells

The effects of combining MEK and either PI3K or mTOR inhibitors on the induction of apoptosis was determined (Fig. 6). In these experiments the cells were cultured in medium containing

Figure 6. Effects of Combination of MEK and PI3K/mTOR Inhibitors on the Induction of Apoptosis in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR Cells. FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were cultured in the presence of 4HT + Test for three days with the following inhibitors: (A) DMSO (negative control), (B) PI3K inhibitor (1 μM LY294002), (C) mTOR inhibitor (10 nM Rapamycin), (D) MEK inhibitor (500 nM UO126), (E) MEK + PI3K inhibitors (500 nM UO126 + 1 μM LY294002), and (F) MEK + mTOR inhibitors (500 nM UO126 + 10 nM rapamycin). Annexin V analysis was performed as described.24

4HT + Test. Suboptimal doses of the MEK, PI3K or mTOR inhibitors were administered to the cells and the effects on the induction of apoptosis determined after three days of incubation (B–D). In some cases, combinations of suboptimal amounts of MEK + PI3K inhibitors or MEK + mTOR inhibitors were evaluated (E and F). When FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were treated with DMSO, most of the cells were not apoptotic (A, 15%). When the cells were treated with suboptimal concentrations of PI3K, mTOR or MEK inhibitors, low levels of apoptosis were observed (B–D, 28–30%). When cells were treated with the MEK + PI3K inhibitor (E), a higher percentage of apoptotic and dead cells (E, 57%) were observed than when the cells were treated with just a MEK (D, 28%) or PI3K inhibitor (B, 28%). This reflects an additive effect of these two inhibitors. Likewise when the cells were treated with both MEK and mTOR inhibitors a large percentage of the cells were apoptotic and dead (75%) demonstrating that upon combining MEK and mTOR inhibitors a greater than additive effect was observed.

Effects of signaling pathways on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis

The effects of IL-3, Raf-1 and Akt-1 induced signaling pathways and chemotherapeutic drugs on the prevention of apoptosis is present in Table 2. IL-3 clearly prevented the induction of apoptosis as 6.6-fold more apoptosis was detected when the cells were not treated with IL-3 for three days. Doxorubicin was able to induce apoptosis, in a dose-dependent fashion, when the cells were cultured with IL-3, 4HT, Test or 4HT + Test. At a dose of 100 nM doxorubicin, close to 100% of the cells were apoptotic. As documented in Table 1, ΔRaf-1:AR activation was able to prevent apoptosis more effectively than ΔAkt-1:ER* activation.

Table 2. Fold increase in apoptosis due to chemotherapeutic drugs and signal transduction inhibitors in FL/ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells (normalized to cells cultured in IL-3).

| No inhibitor | +10 μM U0126 (MEK Inh) | +10 μM LY294002 (PI3K Inh) | +100 nM Rapamycin (mTOR Inh) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

% of Cells Apoptotic |

|||

| No Supplement |

6.6 ± 0.57 |

|

|

|

| IL-3 |

1 ± 0.28 |

2.5 ± 0.44 |

3.2 ± 0.42 |

1.1 ± 0.28 |

| IL-3 + 1 nM Doxorubicin |

0.85 ± 0.27 |

3.1 ± 0.28 |

3.7 ± 0.57 |

1.3 ± 0.30 |

| IL-3 + 10 nM Doxorubicin |

2 ± 0.29 |

4.1 ± 0.57 |

5 ± 0.71 |

1.9 ± 0.29 |

| IL-3 + 100 nM Doxorubicin |

13 ± 1.55 |

13.9 ± 1.72 |

12.9 ± 1.15 |

11 ± 1.29 |

| 4HT (Akt Activation) |

8.3 ± 0.90 |

11.9 ± 1.15 |

13 ± 1.29 |

12.4 ± 1.0 |

| 4HT + 1 nM Doxorubicin |

10.6 ± 1.15 |

12.4 ± 1.28 |

12.9 ± 1.15 |

12.6 ± 1.43 |

| 4HT + 10 nM Doxorubicin |

12.4 ± 1.28 |

13.1 ± 1.42 |

13.3 ± 1.29 |

13.3 ± 1.14 |

| 4HT + 100 nM Doxorubicin |

13.7 ± 0.71 |

14 ± 1.01 |

13.7 ± 0.86 |

13.7 ± 1.28 |

| Testosterone (Raf-1 Activation) |

2.1 ± 0.28 |

9.4 ± 1.00 |

9 ± 1.14 |

6 ± 1.14 |

| Test + 1 nM Doxorubicin |

2 ± 0.29 |

11.1 ± 1.28 |

10.1 ± 1.42 |

8.1 ± 0.85 |

| Test + 10 nM Doxorubicin |

5.7 ± 0.71 |

11.7 ± 1.43 |

10.1 ± 1.14 |

10.1 ± 1.13 |

| Test + 100 nM Doxorubicin |

14 ± 1.14 |

14 ± 1.00 |

12.4 ± 1.64 |

13.6 ± 1.29 |

| 4HT + Test (Akt + Raf-1 Activation) |

4.7 ± 0.57 |

9.6 ± 0.75 |

9.7 ± 1.28 |

7.7 ± 0.86 |

| 4HT + Test + 1 nM Doxorubicin |

4.6 ± 0.43 |

9.5 ± 1.25 |

12.2 ± 1.13 |

11.4 ± 1.28 |

| 4HT + Test + 10 nM Doxorubicin |

8.7 ± 0.86 |

11.7 ± 1.28 |

11.6 ± 1.29 |

12.1 ± 1.42 |

| 4HT + Test + 100 nM Doxorubicin | 13.9 ± 1.15 | 13.9 ± 1.29 | 14 ± 0.43 | 13.7 ± 1.00 |

The effects Raf-1 and Akt activation in the presence of doxorubicin, MEK, mTOR and PI3K inhibitors on the induction of apoptosis was measured by Annexin V/PI after three days of incubation. These experiments were repeated three times and similar results were observed.

Inhibition of MEK and PI3K also induced apoptosis approximately 2.5- and 3-fold respectively when the cells were cultured with IL-3. In contrast, when they were treated with rapamycin in the presence of IL-3, only a 1.3-fold increase in the induction of apoptosis was observed.

The effects of combining classical chemotherapy with targeted therapy were determined. When the cells were cultured with IL-3, MEK or PI3K inhibitors, and 10 nM doxorubicin increases in the induction of apoptosis were observed. However, addition of 100 nM rapamycin to IL-3 and doxorubicin treated cells did not appear to increase the induction of apoptosis.

Addition of MEK, PI3K or mTOR inhibitors increased the induction of apoptosis when only ΔAkt-1:ER* was activated, and essentially almost all of the cells were apoptotic. Similar effects were observed when the 4HT-treated cells were treated with doxorubicin and MEK, PI3K or mTOR inhibitors.

In contrast, more dramatic effects were observed when ΔRaf-1:AR was activated. Similar to the results observed with IL-3, doxorubicin induced a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis when ΔRaf-1:AR was activated. MEK, PI3K and mTOR inhibitors also induced apoptosis when ΔRaf-1:AR was activated. Increases in apoptosis were also observed when the cells that had ΔRaf-1:AR activated, were treated with doxorubicin and MEK, PI3K or mTOR inhibitors.

Interestingly, a higher extent of apoptosis was observed when Raf-1 and Akt-1 were activated. Treatment of cells with activated ΔRaf-1:AR and ΔAkt-1:ER* with MEK, PI3K or mTOR inhibitors increased the extent of apoptosis. Similarly, treatment of Test + 4HT treated cells with doxorubicin resulted in a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis. In summary, these results indicate the dominance of the Raf/MEK/ERK pathway in suppressing apoptosis in these cells and targeting the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways can increase the ability of doxorubicin to induce cell death.

Discussion

In this study, the effects of cytokine-mediated vs. oncogenic Raf-1 and Akt-1 induced signaling in promoting cell cycle progression, gene expression, apoptosis and sensitivity to signal transduction inhibitors were compared in the same cell line. We have previously demonstrated the individual roles of Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR cascades in drug resistance and cell cycle progression.25-27 In this current study, we compared the roles of these pathways in these processes in hematopoietic cells where we can conditionally control the expression of the Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR pathways. Thus we can determine the effects of either normal cytokines or mutated oncogenes on proliferation, gene expression, prevention of apoptosis and sensitivity to either chemotherapeutic drugs or targeted therapy in the same genetic background. IL-3 and Raf-1 were dominant in terms of promoting both cell cycle progression and preventing apoptosis when compared with Akt-1. However, suppression of PI3K or mTOR activity would enhance MEK inhibition. Furthermore, doxorubicin was an effective inducer or apoptosis in response to either cytokine or activation of Raf-1 or Akt-1. These results and other studies indicate that targeting MEK, mTOR and p53 may be an effective means to combat the growth of certain cancers that have deregulated Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR cascades due to mutations in upstream receptors, exchange coupling proteins or intrinsic components of these pathways.28-35

IL-3 induced MEK, ERK and p90Rsk activation, but the effects of IL-3 on these signaling events was often transient suggesting that other signaling pathways or phosphatases were induced that in turn suppressed the initial activation. Activation of Raf-1 induced downstream MEK, ERK and p90Rsk. Prolonged induction of p90Rsk was observed when Raf-1 was activated but only transient activation was detected after Akt-1 activation. Thus in this model system, the effects of cytokine vs. oncogene mediated signaling can be compared. IL-3 or the combination of Raf-1 and Akt-1 activation induced prolonged p70S6K activation, which was not detected for prolonged time periods after activation of Raf-1 or Akt-1 by themselves. IL-3 and Raf-1 activation induced STAT5 and c-Myc protein expression, c-Myc expression was also detected after Akt-1 activation but STAT-5 expression was not observed after Akt-1 activation. Interestingly Raf-1 activation resulted in Elk-1 activation, which was not detected in these experiments after either IL-3 or 4HT treatment. Thus there are differences in the patterns of expression of downstream kinases and transcription factors after cytokine or either Raf-1 or Akt-1 activation. These results indicate that even though a cell has the capability to express these different molecules involved in cell proliferation, they may differ in terms of magnitude as well as temporal activity depending on which signaling cascade is activated. Certain activated oncogenes such as Raf-1 may induce prolonged activation of specific downstream signaling molecules. Such information could be critical in devising appropriate therapies to treat cancers in patients which have mutations activating these pathway components.

The effects of classical chemotherapy on the inhibition of cell cycle progression and the induction of apoptosis were also compared with signal transduction inhibitors which target the Raf/MEK/ERK or PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathways. Doxorubicin is a potent inducer of p53 in cells which have WT p53.10 The induction of p53 activity can be enhanced by treatment of cells with Nutlins which stabilize p53 by inhibiting MDM-2.10,34-36 Classical chemotherapeutic drugs such as doxorubicin or paclitaxel were effective in inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and their death promoting effects could be enhanced upon co-addition of certain signal transduction pathway inhibitors. Signal transduction inhibitors which target the PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways may prove to enhance cancer chemotherapy,31-40 as well as prevent the onset of aging and other proliferative diseases.41-48 Furthermore targeting of the cancer stem cells with combinations of these signal transduction inhibitors and chemotherapy may enhance cancer therapy.4,49-52

Methods

Cell lines and growth factors

Cells were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator with Iscove’s Modified Eagles Medium [(IMEM) Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA] supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA). Conditionally-transformed FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were grown normally in 5% FBS + 500 nM 4 hydroxyl tamoxifen (4HT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), an estrogen receptor antagonist which activates the ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) and 100 nM testosterone (Test, Sigma-Aldrich), which activates the androgen receptor (AR) hormone binding domain contained in ΔRaf-1:AR.24 ΔAkt:ER*(Myr+) contains a mutated ER domain (ER*) which responds to 4HT 100-fold more efficiently than β-estradiol. Thus these cells were maintained in 4HT as opposed to β-estradiol.24 In some experiments, the FL/ΔAkt-1:ER*(Myr+) + ΔRaf-1:AR cells were treated with IL-3 (10% WEHI-3B conditioned medium).

In order to determine the importance of certain signaling pathways in the prevention of apoptosis, cells were treated with the MEK inhibitors U0126, the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or the mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin all purchased from (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) as described.10

Analysis of cell cycle distribution

Cells were incubated at approximately 2 x 105 cells/ml in 3 mls of phenol-red free IMEM containing 5% charcoal stripped (CS) (to avoid estrogens present in FBS which can be removed by charcoal stripping) but lacking 4HT or Test as described.25 This initial time point is designated (Day -1). Twenty-four hours later at the T0 point, IL-3 (10% WCM), 4HT (500 nM), Test (100 nM), 4HT + Test (500 + 100 nM), and doxorubicin or paclitaxel were added to the cultures. Aliquots of approximately 1 x 105 cells (0.5 mls) were subsequently removed at the indicated time points. Analysis of cell cycle distribution was performed as described previously.25

Annexin V apoptotic assays. Annexin V/PI binding assays were performed after three days of incubation as previously described with kits purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN) respectively.24

Western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice with PBS and then cultured in the presence of phenol red free IMEM containing 5% CS FBS (to avoid endogenous estrogen/testosterone like compounds) for 24 h. An aliquot of cells was removed (T0 Hr). Cells were then treated with IL-3, 4HT, Test or 4HT + Test for the indicated time intervals and aliquots removed. Western blots were performed with antibodies specific for MEK, ERK, Akt, p90Rsk-1, p70S6K, STAT5, c-Myc and ELK as we have previously described.10 All antibodies used in this study were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the US Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (NCI R01CA098195) and a Brody Brothers Endowment Fund (MT7826) to J.A.M. A.M.M. was supported by grants from Progetti Strategici Unibo EF 2006 and MIUR PRIN 2008.

02/05/10

02/10/10

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/11487

References

- 1.Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Whelan J, Bertrand FE, Ludwig DE, Bäsecke J, Libra M, Stivala F, Milella M, Tafuri A, et al. Contributions of the Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and Jak/STAT pathways to leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:686–707. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCubrey JA, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, Bertrand FE, Ludwig DE, Bäsecke J, Libra M, Stivala F, Milella M, Tafuri A, et al. Targeting survival cascades induced by activation of Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and Jak/STAT pathways for effective leukemia therapy. Leukemia. 2008;22:708–22. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carracedo A, Baselga J, Pandolfi PP. Deconstructing feedback-signaling networks to improve anticancer therapy with mTORC1 inhibitors. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3805–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Misaghian N, Ligresti G, Steelman LS, Bertrand FE, Bäsecke J, Libra M, Nicoletti F, Stivala F, Milella M, Tafuri A, et al. Targeting the leukemic stem cell: the Holy Grail of leukemia therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:25–42. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKearn JP, McCubrey JA, Fagg B. Enrichment of hematopoietic precursor cells and cloning of multipotential B-lymphocyte precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7414–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCubrey JA, Holland G, McKearn J, Risser R. Abrogation of factor-dependence in two IL-3-dependent cell lines can occur by two distinct mechanisms. Oncogene Res. 1989;4:97–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo MW, Wang X-Y, Algate PA, Arana GF, Hoyle PE, Steelman LS, McCubrey JA. Synergy between AUUUA motif disruption and enhancer insertion results in autocrine transformation of interleukin-3-dependent hematopoietic cells. Blood. 1995;86:3139–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang X-Y, McCubrey JA. Malignant transformation induced by cytokine genes: a comparison of the abilities of germline and mutated interleukin 3 genes to transform hematopoietic cells by transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:487–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang XY, McCubrey JA. Differential effects of retroviral long terminal repeats on interleukin-3 gene expression and autocrine transformation. Leukemia. 1997;11:1711–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCubrey JA, Abrams SL, Ligresti G, Misaghian N, Wong EW, Steelman LS, Bäsecke J, Troppmair J, Libra M, Nicoletti F, et al. Involvement of p53 and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in hematopoietic drug resistance. Leukemia. 2008;22:2080–90. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kornblau SM, Womble M, Qiu YH, Jackson CE, Chen W, Konopleva M, Estey EH, Andreeff M. Simultaneous activation of multiple signal transduction pathways confers poor prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108:2358–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes AR, Brosens JJ, Lam EWF. Resist or die: FOXO transcription factors determine the cellular response to chemotherapy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3133–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.20.6920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ligresti G, Militello L, Steelman LS, Cavallaro A, Basile F, Nicoletti F, Stivala F, McCubrey JA, Libra M. PIK3CA mutations in human solid tumors: role in sensitivity to various therapeutic approaches. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1352–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.9.8255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nimbalkar D, Quelle FW. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling overrides a G2 phase arrest checkpoint and promotes aberrant cell cycling and death of hematopoietic cells after DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2877–85. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hambardzumyan D, Becher OJ, Holland EC. Cancer stem cells and survival pathways. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1371–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palomero T, Dominguez M, Ferrando AA. The role of the PTEN/AKT Pathway in NOTCH1-induced leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:965–70. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papa V, Tazzari PL, Chiarini F, Cappellini A, Ricci F, Billi AM, Evangelisti C, Ottaviani E, Martinelli G, Testoni N, et al. Proapoptotic activity and chemosensitizing effect of the novel Akt inhibitor perifosine in acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2008;22:147–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JT, Lehmann BD, Terrian DM, Chappell WH, Stivala F, Libra M, Martelli AM, Steelman LS, McCubrey JA. Targeting prostate cancer based on signal transduction and cell cycle pathways. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1745–62. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.12.6166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tazzari PL, Tabellini G, Bortul R, Papa V, Evangelisti C, Grafone T, Martinelli G, McCubrey JA, Martelli AM. The insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells exhibiting autocrine insulin-like growth factor-I secretion. Leukemia. 2007;21:886–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez-Vidal A, Mazars A, Gautier EF, Prévost G, Payrastre B, Manenti S. Upregulation of the CDC25A phosphatase down-stream of the NPM/ALK oncogene participates to anaplastic large cell lymphoma enhanced proliferation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1373–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.9.8302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tazzari PL, Cappellini A, Ricci F, Evangelisti C, Papa V, Grafone T, Martinelli G, Conte R, Cocco L, McCubrey JA, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 expression is under the control of the phosphoinositide 3 kinase/Akt signal transduction network in human acute myelogenous leukemia blasts. Leukemia. 2007;21:427–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Follo MY, Finelli C, Bosi C, Martinelli G, Mongiorgi S, Baccarani M, Manzoli L, Blalock WL, Martelli AM, Cocco L. PI-PLCbeta-1 and activated Akt levels are linked to azacitidine responsiveness in high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2008;22:198–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiarini F, Del Sole M, Mongiorgi S, Gaboardi GC, Cappellini A, Mantovani I, Follo MY, McCubrey JA, Martelli AM. The novel Akt inhibitor, perifosine, induces caspase-dependent apoptosis and downregulates P-glycoprotein expression in multidrug-resistant human T-acute leukemia cells by a JNK-dependent mechanism. Leukemia. 2008;22:1106–16. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shelton JG, Steelman LS, Lee JT, Knapp SL, Blalock WL, Moye PW, Franklin RA, Pohnert SC, Mirza AM, McMahon M, et al. Effects of the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signal transduction pathways on the abrogation of cytokine-dependence and prevention of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:2478–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang F, McCubrey JA. p21Cip1 induced by Raf is associated with increased Cdk4 activity in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:4354–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertrand FE, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Shelton JG, White ER, Ludwig DL, McCubrey JA. Synergy between an IGF-1R antibody and Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors in suppressing IGF-1R-mediated growth in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:1254–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steelman LS, Navolanic PM, Sokolosky ML, Taylor JR, Lehmann BD, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Wong EW, Stadelman KM, Terrian DM, et al. Suppression of PTEN function increases breast cancer chemotherapeutic drug resistance while conferring sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors. Oncogene. 2008;27:4086–95. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tallman MS. New agents for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:311–20. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2005.11.006. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poruchynsky MS, Sackett DL, Robey RW, Ward Y, Annunziata C, Fojo T. Proteasome inhibitors increase tubulin polymerization and stabilization in tissue culture cells: a possible mechanism contributing to peripheral neuropathy and cellular toxicity following proteasome inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:940–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathew G, Timm EA, Jr., Sotomayor P, Godoy A, Montecinos VP, Smith GJ, Huss WJ. ABCG2-mediated DyeCycle Violet efflux defined side population in benign and malignant prostate. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1053–61. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krymskaya VP, Goncharova EA. PI3K/mTORC1 activation in hamartoma syndromes: therapeutic prospects. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:403–13. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mavrakis KJ, Wendel HG. Translational control and cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2791–4. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dal Col J, Dolcetti R. GSK-3beta inhibition: at the crossroad between Akt and mTOR constitutive activation to enhance cyclin D1 protein stability in mantle cell lymphoma. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2813–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Z, Hu W, Rajagopal G, Levine AJ. The tumor suppressor p53: cancer and aging. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:842–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korotchkina LG, Demidenko ZN, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Cellular quiescence caused by the Mdm2 inhibitor nutlin-3A. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3777–81. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.10121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pospelova TV, Demidenko ZN, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Gudkov AV, Blagosklonny MV. Pseudo-DNA damage response in senescent cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4112–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva RL, Wendel HG. MNK, EIF4E and targeting translation for therapy. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:553–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiarini F, Fala F, Tazzari PL, Ricci F, Astolfi A, Pession A, et al. Dual inhibition of class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mammalian target of rapamycin as a new therapeutic option for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3520–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skladanowski A, Bozko P, Sabisz M, Larsen AK. Dual inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling and the DNA damage checkpoint in p53-deficient cells with strong survival signaling: implications for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2268–75. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foster DA, Toschi A. Targeting mTOR with rapamycin: one dose does not fit all. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1026–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blagosklonny MV. Aging: ROS or TOR. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3344–54. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blagosklonny MV, Campisi J. Cancer and aging: more puzzles, more promises? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2615–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.17.6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blagosklonny MV. Program-like aging and mitochondria: instead of random damage by free radicals. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:1389–99. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demidenko ZN, Shtutman M, Blagosklonny MV. Pharmacologic inhibition of MEK and PI-3K converges on the mTOR/S6 pathway to decelerate cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1896–900. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. At concentrations that inhibit mTOR, resveratrol suppresses cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1901–4. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demidenko ZN, Blagosklonny MV. Growth stimulation leads to cellular senescence when the cell cycle is blocked. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3355–61. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.21.6919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demidenko ZN, Zubova SG, Bukreeva EI, Pospelov VA, Pospelova TV, Blagosklonny MV. Rapamycin decelerates cellular senescence. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1888–95. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blagosklonny MV. Aging-suppressants: cellular senescence (hyperactivation) and its pharmacologic deceleration. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1883–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.12.8815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blagosklonny MV. Aging, stem cells, and mammalian target of rapamycin: a prospect of pharmacologic rejuvenation of aging stem cells. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:801–8. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blagosklonny MV. Cancer stem cell and cancer stemloids: from biology to therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1684–90. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.11.5167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuart SA, Minami Y, Wang JYJ. The CML stem cell: evolution of the progenitor. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1338–43. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.9.8209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li L, Borodyansky L, Yang Y. Genomic instability en route to and from cancer stem cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1000–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.7.8041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]