Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are a group of lipid kinases that regulate signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation, adhesion, survival and motility. The PI3K pathway is considered to play an important role in tumorigenesis. Activating mutations of the p110α subunit of PI3K (PIK3CA) have been identified in a broad spectrum of tumors. Analyses of PIK3CA mutations reveals that they increase the PI3K signal, stimulate downstream Akt signaling, promote growth factor-independent growth and increase cell invasion and metastasis. In this review, we analyze the contribution of the PIK3CA mutations in cancer, and their possible implications for diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: PIK3CA, gene mutations, PI3K pathway, AKT, cancer

PI3K Signaling

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3Ks) are lipid kinases that phosphorylate phoshoinositides at the D-3 position of the inositol ring generating second messengers that govern cellular activities and promote various biological properties including proliferation, survival, motility and morphology changes. Members of the PI3K family are grouped into three classes according to sequence homology, substrate preference and tissue distribution.1

In terms of regulating cell division and tumorigenesis, the most important PI3K proteins are those that belong to class IA, the catalytic subunit p110α and its associated regulatory subunit p85. In quiescent cells, the regulatory subunit p85 maintains the p110α catalytic subunit in a low-activity state. Upon growth factor stimulation, the SH2 domain [Rous-sarcoma (src) oncogene homology-2 domain] of the p85 subunit binds to phosphorylated tyrosine in receptor tyrosine kinases or their substrate adaptor proteins. This binding relieves the inhibition of p110α subunit and mediates recruitment of this subunit to the plasma membrane.2 Activation of p110α leads to the production of -phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3), which recruits adaptor and effector proteins containing a Pleckstrin Homology Domain (PH domain) to cellular membranes including the protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1

(PDK-1).3 Once at the membrane PKB/Akt is phosphorylated at Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and the mTORC2 complex respectively. Once activated PKB/Akt phosphorylates and actives target proteins involved in many different cellular functions, which span from: cell cycle progression, cell survival, metabolism, ribosome biogenesis, protein translation, RNA transcription and cell motility.4,5

PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 is a substrate of the phosphatase PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog, deleted on chromosome 10), which dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to generate phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2), therefore, it is a negative regulator of PI3K signaling and functions as a tumor suppressor.6 This phosphatase is often mutated, deleted or downregulated in various tumors leading to constitutive activation of the PI3K pathway.7,8

PI3K Signaling Pathway is Altered in Human Cancers

Cancer is caused by alterations in the control and activity of genes that regulate cell growth and differentiation, leading to abnormal cell proliferation. These “cancer-related genes” fall into two major classes that have opposite effects on normal cell proliferation and, sometimes, these altered genes have important effects in promoting cancer. Tumor suppressor genes normally repress cell growth and are inactivated in cancer, while oncogenes, such as protein kinases, which normally stimulate cell growth, become hyperactivated in cancer.9

Deregulation of the PI3K pathway has been directly implicated in several human cancers. The best known genetic alterations of this pathway are: lost of the tumor suppressor PTEN, amplification of genomic region containing Akt and activating point mutations at PI3K.

By using automated sequencing technology, it was demonstrated that the PI3K genes are mutated in human cancers. These studies have identified cancer-specific somatic mutations in several tyrosine kinase and tyrosine phosphatase genes as well as in the PIK3CA gene which encodes the p110α catalytic subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. PIK3CA is a 34 kb gene located on chromosome 3q26.3 that consists of 20 exons coding for 1068 amino acids yielding a 124 kDa size protein.

The first report on PIK3CA gene mutation in human cancers was published by Samuels and colleagues.10 The authors initially analyzed the sequence of eight PI3K and eight PI3K-like genes of primary colorectal tumors and discovered that PIK3CA was the only PI3K gene harboring somatic mutations. Subsequently, somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene have been reported in many human cancer types including cancers of the colon, ovary, breast, brain, liver, stomach and lung.

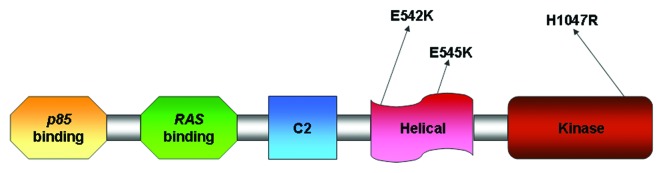

The PIK3CA mutations are somatic, cancer-specific and heterozygous and can be divided into four classes defined by the four domains of the catalytic subunit in which they occur: the adaptor-binding domain (ABD), C2 domain, helical domain and catalytic domain. Analysis of the PIK3CA gene in human tumor samples has identified somatic mutations that affect a total of 38 residues.

The majority of the mutations, “Hotspot” mutation, map to three sites, E542 and E545 in the helical domain (exon 9) and H1047 in the kinase domain (exon 20). E542 and E545 are commonly changed to lysine, whereas H1047 is frequently substituted with arginine (Fig. 1). The crystal structure of the complex between the catalytic subunit of PI3Kα, p110α, and its regulatory subunit, p85α, revealed that many of the mutations occur at residues lying at the interfaces between p110alpha and p85alpha or between the kinase domain of p110alpha and other domains within the catalytic subunit affecting the regulation of kinase activity by p85 or the catalytic activity of the enzyme.11 It was well documented that these mutations cause a gain of protein enzymatic function and induce oncogenic transformation when expressed in primary chicken-embryo fibroblasts and in NIH3T3 cells.12

Figure 1. Description of PIK3CA and its functional domains with the most common somatic mutations.

Somatic Mutations of the PIK3CA Gene in Human Solid Tumors

In Table 1, nucleotide alterations within the coding exons of PIK3CA are reported (Table 1). In 2004, Campbell et al.13 screened a total of 284 primary tumor samples of ovarian, breast and colorectal cancers for mutations in all coding exons of PIK3CA. Among the primary epithelial ovarian cancers only 6% contained somatic mutations, although a clear correlation between mutational status and histologic subtypes was reported. In fact, only 2.3% of the serous and none of 24 mucinous carcinomas harbored somatic PIK3CA mutations compared with 20% of the endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers indicating that the major histologic subtypes such as serous, endometrioid, clear cell and mucinous may arise through different pathways. Additionally, they reported a PIK3CA mutation frequency of 18% in colorectal cancers and 40% in breast cancer. With respect to breast cancers, no association was noted between the presence of PIK3CA mutations and the prognostic/clinical features, including histologic subtype, estrogen/progesterone receptor expression, Her2/neu receptor status, axillary lymph node positivity, grade and/or stage of the tumor. In contrast, Saal et al.14 described a statistically significant correlation between the presence of PIK3CA mutations and the presence of nodal metastases, estrogen/progesterone receptor positivity and Her2/neu receptor overexpression/amplification.

Table 1. Nucleotide alterations within the coding exons of PIK3CA in solid tumors .

| Tumor type (No. of samples screened) |

Nucleotide position (No. of tumors with mutations) |

% of tumors with mutations |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colon (234) |

C311G (1), G317T (1), G323C (1), del332–334 (1), G353A (1), G365A (1), C370A (1), T1035A (1), T1258C (2), G1357C (1), C1616G (1), A1625G (1), A1634G (1), G1635T (1), C1636A (5), A1637C (1), C1981A (1), G2702T (1), T2725C (1), T3022C (1), A3073G (1),C3074A (1), G3129T (2), C3139T (2), A3140T (1) |

32 |

10 |

| Glioblastomas (15) |

T1132C (1), G1048C (1), A2102C (1), G3145A (1) |

27 |

|

| Gastric (12) |

G2702T(1), A3140G (2) |

25 |

|

| Breast (12) |

A3140G (1) |

8 |

|

| Lung (24) |

G1633A (1) |

4 |

|

| Pancreas 11) |

0 |

0 |

|

| Medulloblastomas (12) |

0 |

0 |

|

| Breast (70) |

C1241T (1), T1258C (2), del1352–1366 (1),G1624A (5), G1633A (9), C1636G (1), A3140G (5), A3140T (4) |

40 |

13 |

| Ovarian (182) |

G1624A (2), G1633A (1), C1636A (1), A3140G (7) |

6 |

|

| Colon (32) |

G1633A (2), A1634G (1), C1636A (1), A2198G (1), A3140G (1) |

19 |

|

| Ovarian (198) |

G1633A (1), A1634C (21), C3075T (3), A3127G (1), A3140G (1), T3147G (1) |

12 |

15 |

| Breast (18) |

G1624A (4), G1633A (4), A1634G (1), C3075T (3), A3140T (2), A3140G (2) |

18 |

|

| Endometrial (66) |

G1624A (1), G1624C (1), G1633A (1), A1634G (1), G3019C (1), T3061C (1), A3062C (1), C3104T(1), G3129T (1), C3139T (5), A3140G (6), G3149A (1), C3155A (1), A3194T (1), A3207G (1) |

36 |

17 |

| Head/Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (30) |

G1624A (1), G1633A (1), A1028G (1), C1143G (1), A1173G (6) |

33 |

18 |

| Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (108) |

G1624A (2), G1633A (1), A1637T (1), A3127G (1), A3140G (1), G3145A (1), G3145C (1) |

7 |

19 |

| Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm/Carcinoma of the Pancreas (38) |

C3044T (1), A3140G (1), T1654G (1), C0971T (1) |

11 |

40 |

| Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma (21) |

G1624A (1), G1633A (1), A3140G (1) |

14 |

16 |

| Glioblastoma Multiforme (105) |

G1633A (2), T3061A (1), A3140G (1), A3140T (1) |

5 |

|

| Medulloblastoma (78) |

G1624A (1), G1633A (1), A3140G (1), C3193T (1) |

5 |

|

| Anaplastic |

A1637C (1) |

3 |

|

| Astrocytoma (31) |

|

|

|

| Low-Grade Astrocytoma (24) |

0 |

0 |

|

| Ependymoma (26) | 0 | 0 |

Nucleotide alterations in bold, A3140G (H1047R), G1624A (E542K) and G1633A (E545K), represent the three hot-spot mutations that have been proven to elevate the lipid kinase activity of PIK3CA and activate the Akt signaling pathway.

Interestingly, in ovarian cancer, mutations in p110α are confined almost exclusively to tumors that do not show amplification of the PIK3CA gene. Amplification of PIK3CA is common in ovarian cancers, however mutations at PIK3CA in fact rare in these tumors. By contrast, tumors that lack PIK3CA amplification, such as in breast cancer or colorectal cancer, have mutations more frequently in PIK3CA.

In 2005, Levine et al.15 sequenced the PIK3CA gene in 198 advanced stage epithelial ovarian carcinomas and 72 invasive breast carcinomas and found a mutation rate of 12% for ovarian carcinomas and 18% for breast carcinomas, although no correlation with histologic subtypes and/or clinical/prognostic indicators were observed for either type of cancer. Broderick et al.16 sequenced the PIK3CA gene in 285 brain tumors and found mutations in 14% of anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, 5% of the medulloblastomas and glioblastomas, and 3% of the anaplastic astrocytomas. They also demonstrated that PIK3CA and PTEN mutations were mutually exclusive, suggesting that tumorigenic signaling through this pathway can occur either through activation of PIK3CA or inactivation of PTEN. In contrast, Oda et al.17 analyzed 66 endometrial carcinoma patients and identified a total of 24 (36%) mutations in PIK3CA gene and coexistence of PIK3CA/PTEN mutations at high frequency (26%). They reported that PIK3CA mutations were more frequent in tumors with PTEN mutations (46%) compared with those without PTEN mutations (24%), indicating that the combination of PIK3CA/PTEN alterations might play an important role in development of these tumors.

A study by Qiu et al.18 reported PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). In 38 HNSCC specimens, more than 75% of somatic mutations of PIK3CA were clustered in the helical and kinase domains.

Moreover, Kozaki et al.19 investigated PIK3CA mutations in human oral squamous carcinoma (OSCC) cell lines and primary OSCC tumors. They identified mutations at exons 9 and 20 as well as amplifications in the PIK3CA gene. PIK3CA missense mutations in exons 9 and 20 were identified in 21% of OSCC cell lines and 7.4% of OSCC tumors. An increase in the copy number of PIK3CA was detected in 57.1% of OSCC lines and 16.7% of OSCC tumors. They also reported a significant correlation between somatic mutations of PIK3CA and disease stage: the frequency of mutations was higher in stage IV (16.1%) than in certain early stages (stages I–III) (3.9%). In contrast, amplification of PIK3CA gene was observed at a similar frequency among all stages. Moreover in OSCC cell lines with PIK3CA mutations Akt was highly phosphorylated in comparison to those cell lines lacking PIK3CA mutations, suggesting that somatic mutations of the PIK3CA gene are likely to occur late in the development of OSCC, and play a crucial role through the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma progression.

PIK3CA Mutations are Oncogenic In Vitro and In Vivo

The high frequency of somatic mutations observed in the gene encoding the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K are frequently detected in exon 9, encoding residues of the helical domain, and in exon 20, encoding the kinase domain. These mutations affect preferentially residues that are highly conserved and therefore of critical functional importance. By introducing mutations in three hot spots of the human PIK3CA gene into the corresponding residues of the chicken PIK3CA gene, Kang and colleagues,12 demonstrated that these mutated p110 proteins induced oncogenic transformation when expressed in primary chicken embryo fibroblasts. All three mutants (E542K, E545K and H1047R) display enhanced lipid kinase activity and enhanced enzymatic activity as demonstrated by the high levels of phosphorylated Akt. One year later the same group presented further results demonstrating the oncogenic potential of these mutants also in vivo. The mutants of p110 induced tumors in the chorioallantoic membrane of chicken embryo and caused hemangiosarcomas in the animal.2

These results have been confirmed further by a study by Samuels et al.20 in which they analyzed the oncogenic activity of H1047R mutation using a different approach. They established an isogenic colorectal cancer cell line in which the mutant allele of PIK3CA gene was disrupted by gene targeting. For this purpose, the colorectal cancer cell lines HCT116 was selected because contains the hotspot mutation H1047R in exon 20. HCT116 cells exhibited increased phosphorylation of Akt and the forkhead transcription factors FKHR and FKHRL1 in comparison to the PIK3CA WT isogenic HCT116 cells. Moreover, mutated HCT116 cells had a high apoptotic resistance and an increased ability to migrate and metastatize when injected in the tail vein of athymic nude mice. Similar results was observed using the colorectal cancer cell line DLD1 harboring the hotspot mutation E545K in exon 9.

The in vitro and in vivo oncogenicity of PIK3CA mutants strongly suggests a critical role for these mutated proteins in human malignancies and provides evidence that a kinase with a cancer-specific mutation, such as PI3K, might be an ideal target for specific small molecule inhibitors that could be developed as anticancer drugs. Since, p110α is a critical component of cellular physiology, small molecule inhibitors that discriminate the mutated and wild-type form of PIK3CA might minimize undesirable effects that could arise from interference with the wild-type protein.

The Oncogenic Activity of PIK3CA Mutants is Sensitive to Rapamycin

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, is an antibiotic and immunosuppressant. It has already been used in organ transplant patients and in phase II and III clinical trials in cancer patients for its antitumor activity. Rapamycin inhibits the activity of a protein called mTOR (mammalian Target Of Rapamycin), one of the most important downstream target of.21,22 The mTOR kinase plays a critical role in transducing proliferative signals mediated through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway; it mediates the phosphorylation of downstream proteins such as S6K (p70 S6 kinase) and of the 4EBP (translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein), that are required for both ribosomal biosynthesis and translation of key mRNAs of proteins required for cell proliferation.23,24

It was demonstrated that rapamycin inhibits oncogenic transformation induced by constitutively active PI3K or Akt by interfering with the mTOR-depend phosphorylation of the downstream signaling elements S6K and 4EBP, thereby promoting cell cycle arrest.21 The mTOR-dependent activity, possibly connected to S6K and 4EBP, is highly specific and essential for oncogenic transformation induced by PI3K or Akt. In fact, transformation by diverse oncoproteins such as Ras and Myc, are refractory to inhibition by rapamycin.21

In the PIK3CA mutant-transformed cells S6K and 4EBP are constitutively phosphorylated. This phosphorylation is sensitive to rapamycin, and is therefore mTOR-dependent. Rapamycin, strongly interferes with cellular transformation induced by the PI3K mutants, suggesting that mTOR and its downstream targets are essential components in this transformation process.12

The Crystal Structure of p110α/p85α Complex Elucidates the Mechanisms of PIK3CA Oncogenic Mutations

More than 80% of the PIK3CA mutations occur in exon 9 (helical domain) and in exon 20 (kinase domain). The molecular mechanisms by which these mutations alter the PI3K structure increasing the kinase activity has been the subject of intense investigation.

p110α subunit is composed of five domains: an adaptor-binding domain (ABD), that binds the p85 subunit, a Ras-binding domain (RBD), a C2 domain, a helical domain, and a kinase domain.25,26 In its basal state, the p110α subunit is bound to and inhibited by the regulatory subunit p85α. The p85α subunit is also composed of five domain: an SH3 domain, a GAP domain, an N-terminal SH2 (nSH2) domain, an inter-SH2 domain (iSH2), and a C-terminal SH2 domain (cSH2). The minimal fragment of p85α capable of regulating p110α subunit is the N-terminal SH2 domain (nSH2) linked to the inter-SH2 domain (iSH2).27

The iSH2 domain is a rigid coiled-coil that mediates binding between p85α and the N terminus of p110α, but has no effect on p110α activity. In contrast, the nSH2-iSH2 fragment (p85ni) inhibits p110α activity.28,29 By using a crystallographic approach, Miled and colleagues, resolved the structure of the complex between the iSH2 domain of p85α and the ABD domain of p110α to gain insights into activating mutations in the ABD domain. They reported that oncogenic mutations in ABD domain (R38S, R38H, R88D) do not occur at the interface between ABD and iSH2 domain of the p85α regulatory subunit and therefore, do not disrupt the interaction between these domains as initially thought. However, this structure did not provide evidence about how these mutations might alter the p110α activity.30

The crystal structure of the human full-length p110α in complex with nSH2 and iSH2 domains (niSH2) of p85α subunit was recently resolved by Huang et al.11 This structure revealed two novel inter-domain contacts in which cancer-associated mutations occur: one between the ABD and kinase domain of p110α, and the other between the C2 of p110α and iSH2 of p85α, -demonstrating that many of the mutations occur at residues lying at the interfaces between p110α and p85α or between the kinase domain of p110α and other domains within the catalytic subunit.

Given the interaction between the ABD and kinase domains, revealed by the crystal structure of p110α/niSH2 complex, Huang and colleagues demonstrated that the ABD domain mutations R38S, R38H and R88D disrupt this interaction thereby promoting an alteration in the conformation of the kinase domain that affects the enzymatic activity.

In addition, the identification of the inter-domain contact between the Asp345 in the C2 domain of p110α and the Asp564 and Asp560 in the iSH2 domain of p85α, suggest that the C2 domain mutation Asp345Lys, that occur in some cancers, may affect this interaction, altering the regulatory effect of p85α on p110α.

With respect to the oncogenic mutations occurring in the helical domain of p110α (E542K and E545K), it was proposed that these mutations occur in the interface between the helical domain of p110α and the nSH2 domain of p85α. Moreover, biochemical studies demonstrated that Glu542 and Glu545 interact with Lys379 and Arg340 of p85α nSH2 domain and that these mutated residues may alter the inhibitory activity of p85α on the catalytic subunit.

Lastly in the kinase domain, H1047R is the most common mutation that occurs in a helix at the end of the activation loop of the p110α/p85α complex. This mutation most likely has a direct effect on the conformation of the activation loop, changing its interaction with phosphatidylinositide substrates.

PI3K-Activating Mutations and Chemotherapy Sensitivity

In vitro evidence suggests that PI3K activation is associated with decreased sensitivity to several different chemotherapeutic agents, including paclitaxel, doxorubicin and 5-fluorouracil. It was demonstrated that ovarian cancer cells overexpressing constitutively-active Akt or containing AKT gene amplification were highly resistant to paclitaxel as opposed to cancer cells expressing low Akt levels. Constitutively active Akt inhibits the release of cytochrome c normally induced by paclitaxel thereby promoting apoptosis resistance.31,32

Breast cancer cell lines that express both HER2 and HER3 appear to have a higher degree of Akt activation. Moreover, transfection of HER2 in MCF7 breast cancer cells that express HER3 caused a PI3K-dependent activation of Akt, and was associated with an increased resistance to chemotherapeutic agents including: paclitaxel, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, etoposide and camptothecin. Selective inhibition of PI3K or Akt activity with their respective dominant-negative expression vectors sensitized the cells to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis.33

Recently, Liedtke et al.34 examined whether there is a correlation between activating mutations in the catalytic subunit of PI3K and response to therapy in stage II–III human breast cancer treated with preoperative chemotherapy. They hypothesized that activation of this pathway through somatic mutations may be associated with decreased response to cytotoxic treatment and increased residual cancer volume after chemotherapy.

They examined PIK3CA mutation status in 140 patients with stage II–III breast cancer and correlated the results with clinical and pathological variables, including response to chemotherapy. They did not observe any association between PIK3CA gene status and response to anthracycline-based or anthracycline-containing and paclitaxel-containing chemotherapies. They demonstrated that the frequencies of PIK3CA mutations were similar in patients with extremely chemotherapy-sensitive tumors and those with decreased responses (RCB-I or RCB-II) or even with extensive residual cancer (RCB-III). They also examined whether the effect of PIK3CA mutation on chemotherapy response was different among ER-negative and ER-positive tumors. PIK3CA mutation status was not predictive of response in either ER-positive or ER-negative tumors.

PI3K Pathway as a Mediator of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy Resistance

One of the most successful examples of targeted therapies for epithelial cancers has been the demonstration that breast cancers with amplification of the ERBB2/HER2 oncogene are responsive to trastuzumab (Herceptin), a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the transmembrane domain of the HER2 protein. Patients whose breast cancer cells display overexpression of HER2 protein are candidates for this therapy in both the adjuvant and metastatic settings.35 However, not all women whose tumors overexpress HER2 respond to trastuzumab. Only one-third of women with newly diagnosed advanced breast cancer that overexpresses HER2 demonstrate tumor regression with trastuzumab therapy.36

By using an RNA interference (RNAi) genetic screen, Berns and colleagues identified that PTEN is a mediator of trastuzumab resistance in a HER2-overexpressing breast cancer cell line.37 Given that PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, and 25–30% of human breast cancers harbor somatic mutations in PIK3CA gene, activation of this pathway by somatic mutations could also leads to a similar trastuzumab-resistant phenotype. To test this hypothesis Berns and colleagues retrovirally transduced the breast cancer cell line BT-474 with a constitutively active mutant of PIK3CA (H1047R mutant). They demonstrated that expression of this mutant rendered BT-474 cells almost completely insensitive toward trastuzumab. Furthermore, overexpression of PIK3CA(WT) also conferred resistance to trastuzumab, as amplification of this gene has been demonstrated in other malignancies such as ovarian cancers.

These results were also confirmed by a study by Nagata et al.38 in which they demonstrated that PTEN activation contributes to the effects of trastuzumab antitumor activity. Trastuzumab treatment increased PTEN membrane localization and phosphatase activity by reducing PTEN tyrosine phosphorylation via Src inhibition. PTEN loss in breast cancer cells by antisense oligonucleotides conferred trastuzumab resistance in vitro and in vivo. Patients with PTEN-deficient breast cancers had significantly poorer responses to trastuzumab treatment than those with WT PTEN. Moreover, they demonstrated that PI3K inhibitors restored trastuzumab sensitivity in PTEN-deficient cells, suggesting that PI3K-targeting therapies could overcome this resistance.38 These studies strongly supported the concept that alteration of the PI3K pathway influence trastuzumab resistance, suggesting that combination therapies with PI3K pathway inhibitors and trastuzumab might be more effective for the treatment of patients with breast cancers displaying HER2 overexpression.

In a recent study, Jhawer et al.39 demostrated that PIK3CA mutations predicts response of colon cancer cells to an inhibitory monoclonal antibody directed to the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR), named cetuximab. Cetuximab is monoclonal antibody that has been approved for the treatment of colorectal and head/neck cancers. Jhawer and colleagues screened a panel of 22 colon cancer cells and identified cetuximab-resistant and sensitive cells. Cetuximab-sensitive cells were found to be sensitive to EGF-induced proliferation, while cetuximab-resistant cells were not, suggesting that cells dependent on ligand mediated canonical activation of this pathway were sensitive to cetuximab. Moreover, examination of the mutation status of signaling components downstream of EGFR demonstrated that cell lines WT for PIK3CA/PTEN were significantly more sensitive to cetuximab than were cells with activating PIK3CA mutations or loss of PTEN expression. Consistently, the PIK3CA mutant HCT116 cell line was highly resistant to cetuximab, while a modest, although statistically significant response, was observed in the PIK3CA WT isogenic HCT116 cells. Lastly, cell lines mutant for both PIK3CA/PTEN and K-RAS/BRAF were highly resistant to cetuximab, indicating that mutations that constitutively and simultaneously activate the Ras and PI3K pathways confer maximal resistance to cetuximab.

Summary

The p110α protein is a class I PI3-kinase catalytic subunit. The human p110α protein is encoded by the PIK3CA gene. Recent evidences has demonstrated that the PIK3CA gene is mutated in a range of human cancers including: colon, ovary, breast, brain, liver, stomach and lung. Analysis of the PIK3CA gene in human cancer samples have identified somatic point mutations that affect a total of 38 residues contained in various domains of p110α. They are localized mainly in two hotspots: the helical (exon 9) and kinase domains (exon 20). In the helical domain, residues E542 and E545 are often mutated to lysine, whereas in the kinase domain residue H1047 is changed to arginine.

The three PI3Kα mutant proteins display elevated kinase activity compared with WT PI3Kα, and have the potential to transform chicken-embryo fibroblasts and NIH-3T3 cells. The molecular mechanism by which the above mutations activate PI3Kα, has been elucidated by determining the crystal structure of the p110α subunit in complex with nSH2 and iSH2 domains (niSH2) of p85α subunit, suggesting that mutations occurring in the p110α subunit may disrupt the p110α/p85α complex, altering p110α enzymatic activity.

In vitro evidence suggests that PI3K activation is associated with decreased sensitivity to several different chemotherapeutic agents, including paclitaxel, doxorubicin or 5-fluorouracil. However, the in vitro data have not been confirmed in vivo. In a comparative analysis between PIK3CA mutation status and response to chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer, PIK3CA mutations were not associated with altered sensitivity to preoperative anthracycline-based or taxane-based chemotherapies in ER-positive and ER-negative breast tumors.

On the contrary, the finding that alteration of PI3K pathway is involved in the resistance to treatment of breast cancer patients with trastuzumab, suggest that assessment of PIK3CA mutation status is required for optimal prediction of disease progression after trastuzumab therapy for breast cancer. Moreover, mutated kinases with oncogenic potential, such as PIK3CA, are ideal drug targets for cancer therapy because mutated forms of these proteins are exclusive of tumor cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Lega Italiana per la Lotta contro i Tumori (M.L. and F.S.).

02/19/09

02/23/09

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/8255

References

- 1.Kumar A, Carrera AC. New functions for PI3K in the control of cell division. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1696–8. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.14.4492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bader AG, Kang S, Vogt PK. Cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA are oncogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1475–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corvera S, Czech MP. Direct targets of phosphoinositide 3-kinase products in membrane traffic and signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:442–6. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01366-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazil DP, Park J, Hemmings BA. PKB binding proteins. Getting in on the Akt. Cell. 2002;111:293–303. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01083-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoeli-Lerner M, Toker A. Akt/PKB signaling in cancer: a function in cell motility and invasion. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:603–5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.6.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vazquez F, Devreotes P. Regulation of PTEN function as a PIP3 gatekeeper through membrane interaction. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1523–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.14.3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson L, Parsons R. PTEN: life as a tumor suppressor. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:29–41. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leslie NR, Downes CP. PTEN function: how normal cells control it and tumour cells lose it. Biochem J. 2004;382:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinberg RA. How cancer arises. Sci Am. 1996;275:62–70. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0996-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CH, Mandelker D, Schmidt-Kittler O, Samuels Y, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Gabelli SB, Amzel LM. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318:1744–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang S, Bader AG, Vogt PK. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mutations identified in human cancer are oncogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:802–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408864102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell IG, Russell SE, Choong DY, Montgomery KG, Ciavarella ML, Hooi CS, Cristiano BE, Pearson RB, Phillips WA. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saal LH, Holm K, Maurer M, Memeo L, Su T, Wang X, Yu JS, Malmström PO, Mansukhani M, Enoksson J, et al. PIK3CA mutations correlate with hormone receptors, node metastasis, and ERBB2, and are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2554–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472-CAN-04-3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine DA, Bogomolniy F, Yee CJ, Lash A, Barakat RR, Borgen PI, Boyd J. Frequent mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2875–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broderick DK, Di C, Parrett TJ, Samuels YR, Cummins JM, McLendon RE, Fults DW, Velculescu VE, Bigner DD, Yan H. Mutations of PIK3CA in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, high-grade astrocytomas, and medulloblastomas. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5048–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oda K, Stokoe D, Taketani Y, McCormick F. High frequency of coexistent mutations of PIK3CA and PTEN genes in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10669–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu W, Schönleben F, Li X, Ho DJ, Close LG, Manolidis S, Bennett BP, Su GH. PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1441–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Pimkhaokham A, Hasegawa S, Tsuda H, Omura K, Inazawa J. PIK3CA mutation is an oncogenic aberration at advanced stages of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00343.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuels Y, Diaz LA, Jr., Schmidt-Kittler O, Cummins JM, Delong L, Cheong I, Rago C, Huso DL, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:561–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki M, Blazek E, Vogt PK. A role of the kinase mTOR in cellular transformation induced by the oncoproteins P3k and Akt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:136–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris TE, Lawrence JC., Jr. TOR signaling. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:re15. doi: 10.1126/stke.2122003re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonenberg N, Gingras AC. The mRNA 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E and control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:268–75. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(98)80150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield MD. Signaling by distinct classes of phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:239–54. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296:1655–7. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, Wjasow C, Backer JM. Regulation of the p85/p110alpha phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Distinct roles for the n-terminal and c-terminal SH2 domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30199–203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhand R, Hara K, Hiles I, Bax B, Gout I, Panayotou G, Fry MJ, Yonezawa K, Kasuga M, Waterfield MD. PI 3-kinase: structural and functional analysis of intersubunit interactions. EMBO J. 1994;13:511–21. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klippel A, Escobedo JA, Hirano M, Williams LT. The interaction of small domains between the subunits of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase determines enzyme activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2675–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.4.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miled N, Yan Y, Hon WC, Perisic O, Zvelebil M, Inbar Y, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Wolfson HJ, Backer JM, Williams RL. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science. 2007;317:239–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1135394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin W, Wu L, Liang K, Liu B, Lu Y, Fan Z. Roles of the PI-3K and MEK pathways in Ras-mediated chemoresistance in breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:185–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page C, Lin HJ, Jin Y, Castle VP, Nunez G, Huang M, Lin J. Overexpression of Akt/AKT can modulate chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(1A):407–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knuefermann C, Lu Y, Liu B, Jin W, Liang K, Wu L, Schmidt M, Mills GB, Mendelsohn J, Fan Z. HER2/PI-3K/Akt activation leads to a multidrug resistance in human breast adenocarcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3205–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liedtke C, Cardone L, Tordai A, Yan K, Gomez HL, Figureoa LJ, Hubbard RE, Valero V, Souchon EA, Symmans WF, et al. PIK3CA-activating mutations and chemotherapy sensitivity in stage II-III breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R27. doi: 10.1186/bcr1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab--mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel CL, Cobleigh MA, Tripathy D, Gutheil JC, Harris LN, Fehrenbacher L, Slamon DJ, Murphy M, Novotny WF, Burchmore M, et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab as a single agent in first-line treatment of HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:719–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berns K, Horlings HM, Hennessy BT, Madiredjo M, Hijmans EM, Beelen K, Linn SC, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Hauptmann M, et al. A functional genetic approach identifies the PI3K pathway as a major determinant of trastuzumab resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagata Y, Lan KH, Zhou X, Tan M, Esteva FJ, Sahin AA, Klos KS, Li P, Monia BP, Nguyen NT, et al. PTEN activation contributes to tumor inhibition by trastuzumab, and loss of PTEN predicts trastuzumab resistance in patients. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jhawer M, Goel S, Wilson AJ, Montagna C, Ling YH, Byun DS, Nasser S, Arango D, Shin J, Klampfer L, et al. PIK3CA mutation/PTEN expression status predicts response of colon cancer cells to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1953–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schönleben F, Qiu W, Remotti HE, Hohenberger W, Su GH. PIK3CA, KRAS, and BRAF mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/carcinoma (IPMN/C) of the pancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:289–96. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0285-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]