Abstract

Background

The pathophysiology of chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) is not fully understood; however, it has been hypothesized that a subset of people with CIU may have an autoimmune disease and that peripheral cutaneous nerve fibers may be involved in CIU. Similarly, it has been postulated that fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is an autoimmune disorder and may be associated with alterations of peripheral cutaneous nerve fibers. Accordingly, the present study aimed to determine whether the frequency of FMS is higher in patients with CIU.

Material/Methods

A total of 72 patients with CIU and 67 sex- and age-matched healthy controls were included. Urticaria activity score (UAS), fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ), tender point number, and visual analogue scale (VAS) were assessed.

Results

The frequency of FMS was similar between the groups (9.7% vs. 4.5%, p=0.32). However, symptom duration of FMS was significantly longer, and tender point number and FIQ were significantly higher in patients with CIU than in controls. In addition, patients with CIU had significantly higher VAS scores. UAS was significantly correlated with presence of FMS, symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores. Logistic regression analysis revealed that UAS was an independent predictor of presence of FMS (β=0.34, p=0.003).

Conclusions

Frequency of FMS was slightly, but not significantly, higher in patients with CIU than in controls. However, symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores were significantly higher in patients with CIU, and UAS reflecting severity of the disease was significantly and independently associated with presence of FMS.

Keywords: chronic urticaria, fibromyalgia syndrome, frequency, urticaria activity score, fibromyalgia impact questionnaire

Background

Urticaria is a common condition, affecting up to 20% of the general population. Chronic urticaria (CU) is defined as episodes extending beyond 6 weeks and accounts for 30% of cases [1,2]. The causes of CU cannot be detected in the majority of cases and, hence, the diagnosis of chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU) is made [3,4]. The incidence of CIU is higher in women [2]. Although the underlying pathophysiologic causes of CU is not fully understood in the majority of cases, there has been substantial evidence that peripheral cutaneous nerve fibers may be involved, because certain neuropeptides have been found to be enhanced in CU. In addition, poly-modal and chemo-sensitive small cutaneous nerve fibers have been shown to participate in skin inflammation [5,6]. Alternatively, it has been suggested that there is a neuro-immune linkage between cutaneous sensory nerves and target effector skin cells, causing dysfunctions of peripheral nervous system and pathogenic events in allergic inflammatory skin diseases [6,7].

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), one of the most common chronic musculoskeletal pain disorders, is defined as presence of chronic (for 3 months or more) widespread pain and pain on palpation of at least 11 of 18 tender point sites throughout the body [8]. In addition, several additional symptoms have been reported in patients with FMS, such as fatigue, sleep disruption, anxiety and depression, headache, and concentration problems [8]. The prevalence of FMS is higher in women, and it has been suggested that FMS is a neuropathic pain syndrome [9,10]. Accordingly, it has been suggested that FMS represents a state of dysfunction of descending, anti-nociceptive pathways, and skin biopsies in patients with FMS show both specific receptors and characteristic electron microscope findings, and increased axon reflex flare reaction to mechanical and chemical stimuli [11]. Moreover, since cutaneous sensory C fibers can initiate neurogenic inflammation, such neurogenic inflammation is located in the skin of the patients with FMS [12–14].

Although substantial evidence exists that CIU is associated with involvement of peripheral cutaneous nerve fibers, and the alteration and dysfunction in the peripheral cutaneous nerve fibers can exist in patients with FMS, there is limited data on the frequency of FMS in patients with CIU. Accordingly, in the present study we aimed to evaluate whether the frequency of FM is higher in patients with CIU.

Material and Methods

Study population

A total of 72 patients with CIU (mean age: 36.4±13.0, 25 male) and 67 sex- and age-matched healthy controls (mean age: 35.5±12.1, 20 male) were included. Inclusion criteria were existence of episodes extending beyond 6 weeks duration for patients with CIU. All patients with CIU and controls had no history of any systemic disease, including musculoskeletal, neurologic, inflammatory, endocrine, or the other clinically significant chronic diseases. In addition, subjects with excessive alcohol consumption (>120 g/day) and current smokers were also excluded. To detect disease severity, urticarial activity was measured using the urticarial activity score (UAS) [15,16]. To measure UAS, all patients with CIU were questioned to determine the number urticarial plaques that occurred within the last week (0 = none, 1 = mild (≤20 plaques/24-hour), 2 = moderate (21–50 plaques/24-hour), and 3 = severe (>50 plaques/24-hour), and severity of pruritus (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe) [15,16]. Also, dermatological life quality index (DLQI) was evaluated in all patients. All patients with CIU and controls were also questioned in detail to search for symptoms and signs of FMS. The severity of FMS was detected using a validated Turkish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) forms, which contains 10 self-administered instruments covering physical functioning, work status, depression, anxiety, sleep, pain, stiffness, fatigue, and well-being [17]. A visual analog scale (VAS: from 0 = no pain to 10 = the worst pain) was used to measure pain score.

Statistical analysis

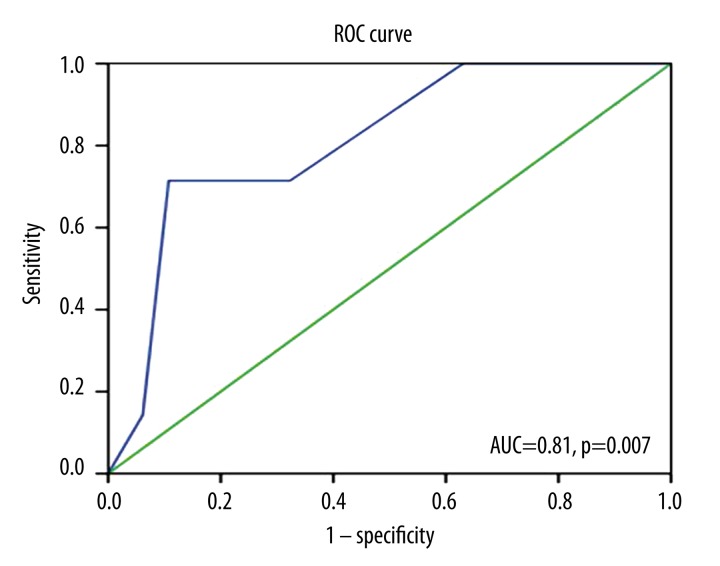

The analyses were performed using SPSS 9.0 (SPSS for windows 9.0, Chicago, IL). Categorical variables were defined as number and percentage. Numeric data are expressed as mean ±SD. The groups were compared using the chi-squared test for categorical variables. The t test or Mann-Whitney U test (for comparison of a characteristic across the groups if that characteristic did not have a normal distribution) was used to compare continuous variables. Correlation analyses were performed using Pearson or Spearman’s (if the characteristic did not have a normal distribution) correlation matrix. Prediction of independent variables was obtained by a stepwise, forward, multiple regression model including potential confounders. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was determined to evaluate the predictive performance of UAS to detect presence of FMS. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) and its standard error were calculated. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the study population

The groups were comparable in respect to age, sex, place of residency, education status, and BMI. As expectedly, urticarial activity score was significantly higher in patients with CIU than in controls. The frequency of FMS was similar between the groups (9.7% vs. 4.5%, p=0.32). However, symptom duration of FMS was significantly longer, and tender point number and FIQ were significantly higher in patients with CIU than in the controls. In addition, patients with CIU had significantly higher VAS scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical features and findings of the fibromyalgia in the study groups.

| Clinical Features | Patients with CIU (72) | Controls (67) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 36.4±13.0 | 35.5±12.1 | 0.68 |

| Gender (male/female) | (25/47) | (20/47) | 0.59 |

| Place of residency (rural/city) | (29/43) | (27/40) | 0.98 |

| Education duration (year) | 7.6±1.4 | 7.7±1.4 | 0.95 |

| Weight (kg) | 71.2±14.8 | 70.7±14.4 | 0.84 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.4±4.9 | 26.3±4.9 | 0.91 |

| CIU disease duration (month) | 71.1±51.5 | – | – |

| UAS | 3.14±1.39 | 0.06±0.05 | <0.001 |

| DLQI | 14.2±9.6 | – | – |

| Presence of FMS (n,%) | 7(9.7) | 3(4.5) | 0.32 |

| Symptom duration of FMS (year) | 15.5±6.2 | 3.2±0.8 | 0.005 |

| Tender point number | 3.11±4.30 | 1.45±2.74 | 0.007 |

| FIQ score | 23.8±19.9 | 7.43±12.15 | <0.001 |

| VAS score | 1.64±2.38 | 0.81±1.58 | 0.01 |

CIU – chronic idiopathic urticaria; BMI – body-mass index; UAS – urticaria activity score; FMS – fibromyalgia syndrome; FIQ – Fibromyalgia impact questionnaire; VAS – visual analog scale.

In patients with CIU, the urticarial activity score was significantly correlated with presence of FMS, symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores. Disease duration of CIU was significantly correlated with symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and VAS score. Similarly, DLQI score was significantly correlated with presence of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ score (Table 2). Furthermore, logistic regression analysis revealed that UAS was an independent predictor of the presence of FMS (β=0.34, p=0.003). We also demonstrated that UAS was an accurate and significant predictor of the presence of FMS on the ROC curve (p=0.007). The area under the curve (AUC) was 81% (95% confidence interval was 0.66–0.97; Figure 1). The best cut-off value of UAS to predict the presence of FMS was 5, with a sensitivity of 89%, a specificity of 72%, a positive predictive value of 87%, and a negative predictive value of 62%.

Table 2.

Relationships of the markers reflecting severity of urticaria to the markers representing severity of fibromyalgia.

| Correlations with r | UAS | Disease duration | Dermatologic life quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of FMS | .34** | .17 | .24* |

| Symptom duration of FMS | .30** | .48*** | .20 |

| Tender point number | .32** | .25* | .34** |

| FIQ score | .26** | .21 | .45*** |

| VAS score | .28** | .24* | .14 |

UAS – urticaria activity score; DLQI – dermatological life quality index; FMS – fibromyalgia syndrome; FIQ – fibromyalgia impact questionnaire; VAS – visual analog scale.

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed);

correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed);

correlation is significant at the 0.0001 level (2-tailed).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of UAS for the presence of FMS. Diagonal segments are produced by ties. UAS – urticaria activity score; FMS – fibromyalgia syndrome; AUC – area under the curve.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that the frequency of FMS was slightly, but not significantly, higher in patients with CIU than in sex- and age-matched controls (9.7% vs. 4.5%). However, there were significant differences between the groups in presence of FMS, symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores. Furthermore, in patients with CIU, UAS (reflecting severity of the disease) was significantly and independently associated with presence of FMS. UAS was also correlated with symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores.

Although the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of CIU are not clearly understood, autoimmunity, which is detected in 45% of the subjects with CIU, has been suggested as one of the etiologic factors [18]. Accordingly, Leznoff et al. [19] reported that about 15% of the subjects with CIU had evidence of associated thyroid autoimmunity, whereas less than 6% of normal subjects had thyroid autoimmunity. The authors also found that most patients with thyroid autoimmunity had relentless and severe urticaria and/or angioedema, and they hypothesized that a subset of people with CIU may have an autoimmune disease. In line with these findings, Grattan et al. [20] showed that 7 of 11 autologous sera from patients with CIU re-injected intradermal produced a weal at the site of injection, but no response was detected in the 19 control subjects. Moreover, marked neutrophil infiltrate was seen within and around small dermal blood vessels at the injection site in the majority of patients with CIU, but this did not correlate with weal formation. However, the cellular response was mild and mainly mononuclear in control subjects. Similarly, it has been postulated that FM is an autoimmune disorder and may include dysfunction of purine nucleotide metabolism and nociception.

Although both CIU and FMS are postulated to be autoimmune disorders, there are limited and contradictory data on the potential association between CIU and FMS. In a pilot study, Torresani et al. [21] aimed to determine whether patients with CU were also affected by FMS. The study included a total of 126 patients with CU, and the authors found that, unexpectedly, over 70% of patients with CU had FMS. The corresponding proportion for 50 control dermatological patients was 16%, which was much higher than the previously published data for the Italian general population (2.2%). The authors hypothesized that dysfunctional cutaneous nerve fibers of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome may release neuropeptides, which, in turn, may induce dermal micro-vessel dilatation and plasma extravasation. They have also postulated that some neuropeptides may favor mast cell degranulation, which stimulates nerve endings, thus providing positive feedback. They concluded that in many patients CU may thus be viewed as a consequence of FMS, and speculated that skin neuropathy or FMS may trigger neurogenic skin inflammation resulting in CU. In contrast, Hapa et al. [22] recently reported that only 26% of patients with CU and 20.8% of controls had FMS and no significant difference was observed between the groups. They also suggested that there is no significant difference between patients with positive autologous serum skin test and patients with negative autologous serum skin test, and no significant difference was observed in the frequency of FMS between the patients, either when divided into 2 groups according to UAS or when divided into 2 groups according to disease duration. In line with the results of Hapa et al., in the present study there was no statistically significant difference between the patients with CIU and controls in the frequency of FMS. However, in our study, symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores were significantly different between the groups. Other contrasting findings in our study were that UAS reflecting severity of the disease was significantly and independently associated with presence of FMS, and UAS was also correlated with symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores. In addition, we found that UAS was an accurate and significant predictor of the presence of FMS on the ROC curve, and the best cut-off value of UAS to predict presence of FMS was 5, with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 72%.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study suggest that, as compared to sex- and age-matched healthy controls, FMS was slightly, but not significantly, more frequent in patients with CIU. However, there were significant differences between the groups in respect to symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores. Furthermore, in patients with CIU, UAS (reflecting severity of the disease) was significantly and independently associated with the presence of FMS, and the best cut-off value of UAS to predict presence of FMS was 5, with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 72%. UAS was also correlated with symptom duration of FMS, tender point number, and FIQ and VAS scores.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interest disclosures (none)

The authors have no personal or financial relationships that have any potential to inappropriately influence (bias) the study, and no financial or other potential conflicts of interest exist (including involvement with any organization with a direct financial, intellectual, or other interest in the subject of the manuscript) regarding the manuscript. In addition, we received no grants and sources of financial support related to the topic or topics of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Champion RH, Roberts SO, Carpenter RG, Roger JH. Urticaria and angio-oedema. A review of 554 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:588–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1969.tb16041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:664–72. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boguniewicz M. The autoimmune nature of chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:433–38. doi: 10.2500/aap.2008.29.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholzen T, Armstrong CA, Bunnett NW, et al. Neuropeptides in the skin: interactions between the neuroendocrine and the skin immune systems. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinhoff M, Ständer S, Seeliger S, et al. Modern aspects of cutaneous neurogenic inflammation. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1479–88. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raap U, Kapp A. Neuroimmunological findings in allergic skin diseases. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:419–24. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000183111.78558.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–72. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Lavin M. Fibromyalgia is a neuropathic pain syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:827–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin RH, Fields HL. Fibromyalgia from the perspective of neuropathic pain. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005;75:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH. Skin biopsy findings: implications for the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69:141–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Kim DH, Oh DH, Clauw DJ. Characteristic electron microscopic findings in the skin of patients with fibromyalgia – preliminary study. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:407–11. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0807-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salemi S, Rethage J, Wollina U, et al. Detection of interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skin of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:146–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eneström S, Bengtsson A, Frödin T. Dermal IgG deposits and increase of mast cells in patients with fibromyalgia – relevant findings or epiphenomena? Scand J Rheumatol. 1997;26:308–13. doi: 10.3109/03009749709105321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, et al. EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy. 2006;61:321–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, et al. EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2006;61:316–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarmer S, Ergin S, Yavuzer G. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. Rheumatol Int. 2000;20:9–12. doi: 10.1007/s002960000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong LJ, Balakrishnan G, Kochan JP, et al. Assessment of autoimmunity in patients with chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:461–65. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leznoff A, Sussman GL. Syndrome of idiopathic chronic urticaria and angioedema with thyroid autoimmunity: a study of 90 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84:66–71. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grattan CE, Wallington TB, Warin RP, et al. A serological mediator in chronic idiopathic urticaria – a clinical, immunological and histological evaluation. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:583–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb04065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torresani C, Bellafiore S, De Panfilis G. Chronic urticaria is usually associated with fibromyalgia syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:389–92. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hapa A, Ozdemir O, Evans SE, et al. Evaluation of the frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with chronic urticarial. Turkderm. 2012;46:202–5. [Google Scholar]