Abstract

Objective

This article reviews and illustrates the anatomy and pathology of the masticator space (MS).

Background

Pathology of the masticator space includes inflammatory conditions, vascular lesions, and tumours. Intrinsic tumours of this space can be benign and malignant, and they may arise from the mandibular ramus, the third division of the trigeminal nerve, or the mastication muscles. Malignant tumours may appear well defined and confined by the masticator fascia, without imaging signs of aggressive extension into neighbouring soft tissues. Secondary invasion of the masticator space can also occur with tumours of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, oral cavity, and parotid glands. Perineural tumour spread (PNS), especially along the trigeminal nerve, can also occur with masticator space malignancies.

Conclusion

Masses of the MS are difficult to evaluate clinically, and computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) images are essential for the diagnosis and characterisation of these lesions. Malignant tumours may appear well defined and confined by the fascia. Thus, when a mass is identified, a biopsy should be done promptly. PNS may occur in tumours involving the MS and its recognition on imaging studies is essential to plan the appropriate treatment.

Teaching points

• Differentiating between intrinsic and extrinsic lesions is essential to the differential diagnosis

• Infections of the MS may cross the fascia and mimic neoplasms on imaging studies

• Malignant tumours may show no aggressive signs, such as bone erosion or violation of the fascia

• Perineural spread (PNS) is often clinically silent and frequently missed at imaging and leads to tumour recurrence

Keywords: Computed tomography, Magnetic resonance, Masticatory muscles, Neoplasms, Mandibular nerve

Background

The masticator space contains the mastication muscles, ramus of the mandible, and mandibular nerve. Because clinical assessment of lesions in this space may be difficult, CT and MR imaging is important for the characterisation and mapping of the pathology.

Inflammatory conditions of the space are particularly common and are usually odontogenic in origin. Lymphovascular malformations are also common, particularly in children. Benign and malignant tumours may arise from the different contents of the space, and malignant tumours may appear well defined and confined by the fascia, without signs of aggressiveness. Tumours of the pharynx and parotid gland may also invade the MS. PNS can also occur with malignancies arising within this space.

Anatomy of the masticator space

The masticator spaces are paired supra-hyoid cervical spaces on each side of the face that extend from the angle of the mandible to the parietal calvarium [1]. Each space is delineated by a superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (SLDCF). At the lower border of the mandible, the SLDCF splits into two layers: an inner layer that extends deep to the medial pterygoid muscle and attaches to the skull base medial to the foramen ovale and an outer or superficial layer that covers the masseter muscle, attaches to the zygomatic arch, and then continues superiorly to encase the temporalis muscle. These two layers fuse along the anterior and posterior borders of the mandibular ramus, enveloping the space [2, 3] (Fig. 1).

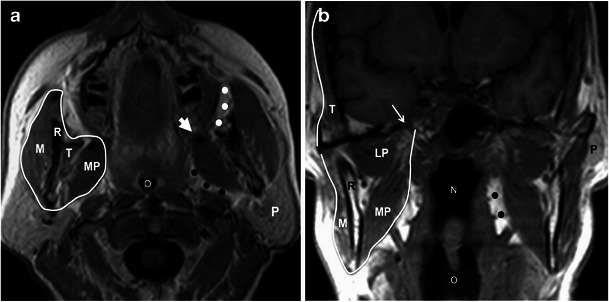

Fig. 1.

Anatomy of the masticator space. a Axial and b coronal T1W MR images show the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia (white line) enveloping the space, the ramus of the mandible (R), masseteric muscle (M), medial pterygoid muscle (MP), lateral pterygoid muscle (LP), and temporalis muscle (T). The foramen ovale (thin arrow in b), from which the mandibular nerve passes. Also note the close relation of the space with the buccal fat pad (white dots) anteriorly, with the parotid gland (P) posterolaterally, and with the prestyloid parapharyngeal space (black dots) medially. Large white arrow (a) points to the expected location of the pterygomandibular raphe. N nasopharynx, O oropharynx

The masticator space contains the mastication muscles, posterior mandible, and mandibular nerve [3, 4]. Figure 1 shows that the four mastication muscles are the medial and lateral pterygoids, masseter, and temporalis [3, 4]. The lateral pterygoid muscle, the only muscle lying within the space without contributing to the encasing fascia, has the primary function of opening the mouth, whereas the medial pterygoid, masseter, and temporalis muscles act to close it [3, 5].

The third division of the trigemial nerve—the mandibular nerve (V3)—has its origin in the Gasserian ganglion in Meckel’s cave. It then enters the masticator space through the foramen ovale. V3 supplies motor function to the mastication muscles, as well as the tensor veli palatini, mylohyoid, and anterior belly of the digastric muscle (Fig. 1). It also provides sensory innervation to the lower face, temporal region, mandibular teeth, buccal and mandibular gingival mucosa, and the anterior two thirds of the tongue [3].

Imaging of the masticator space

Clinical examination of the masticator space is difficult because of its extension deep to the ramus of the mandible. Imaging techniques are thus essential to detect and characterise the pathology of this space. Computed tomographic (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imagings are the preferred techniques and are both equally reliable in detecting lesions [1]. CT is better than MR in detecting subtle erosions of the cortex of the mandible and provides excellent detection and characterisation of the tumour matrix mineralisation. CT is also better at depicting the causes of inflammation or infection, such as odontogenic abscesses or salivary gland stones [1, 3]. MR has higher soft tissue contrast resolution than CT and better depicts muscle invasion by tumours [1, 3]. It also provides better assessment of mandibular medullary disease and is more sensitive for detecting perineural tumour spread [1, 3, 6].

Recently, functional MR techniques have been applied to the study of the masticator space. Diffusion-weighted imaging can be valuable in distinguishing between benign solid and malignant tumours [7], and MR spectroscopy may be potentially useful in the differentiation of chronic infections from malignant tumours of the space [8]. The clinical value of these techniques has not yet been shown, and more studies are necessary before their usefulness can be ascertained.

Pathology of the masticator space

Pathology of the masticator space includes pseudolesions, inflammatory conditions, vascular lesions, and tumours. Intrinsic tumours of the space can be benign or malignant and arise from the nerves, mandible, or soft tissues. Secondary tumour extension to the masticator space is also common and may occur by direct extension or by perineural tumoral spread.

Inflammation

Infections of the masticator space are more frequent than tumours and are frequently odontogenic in origin (i.e., tooth extraction, caries with severe gingivitis, etc.) [9]. Less commonly, infections of the masticator space may be an extension of an infection arising in the parotid or submandibular glands or a tonsillar abscess [3]. When inflamed, the muscles appear enlarged and enhance in a non-homogeneous manner. Abscesses may be confined to the masticator space or be transpatial and manifest as well-defined fluid collections surrounded by an irregularly enhancing capsule [3, 4] (Fig. 2).

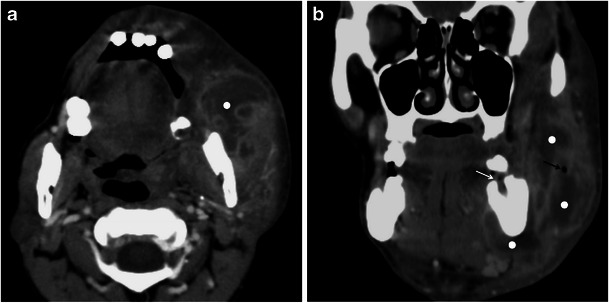

Fig. 2.

A 35-year-old man with an abscess in the masticator space. a Axial and b reformatted coronal contrast-enhanced CT images show a multiloculated fluid collection (white dots), with a gas bubble (black arrow) and enhancing walls, compatible with an abscess. The cause of the abscess was a tooth infection (white arrow in b pointing to a empty mandibular dental socket)

Vascular anomalies

Vascular anomalies are separated into two major groups: haemangiomas and vascular malformations. The haemangioma is a true neoplasm and constitutes the most common benign paediatric tumour of the masticator space [5]. It appears in the first months of life, goes through a proliferative phase, and then involutes during the first decade of life [5, 10, 11]. On imaging studies it appears as a well-circumscribed, slightly lobulated mass, isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images (WI) and hyperintese on T2-weighted images (WI). Significant enhancement after contrast administration is common, especially during its proliferative phase [5].

Vascular malformations are present at birth but may not be clinically apparent until early infancy or childhood. As opposed to haemangiomas, they do not regress or involute, but enlarge as the patient ages. Based on haemodynamic flow characteristics, they are divided into high-flow and low-flow malformations. The low-flow malformations do not have arterial components and include venous, lymphatic, and mixed malformations [5, 10, 11].

Venous malformations are common in the neck region. They can infiltrate along the fascial planes or be confined to a muscle, most frequently the masseter [4]. These lesions have soft tissue density on CT. On MR they show intermediate signal intensity on T1WI and high signal intensity on T2WI because of the slow venous flow. Calcified phleboliths are diagnostic and manifest as round foci of high attenuation on CT or low-signal intensity on MR [3, 4] (Fig. 3). Contrast studies may show enhancement of the slow-flowing venous channels.

Fig. 3.

A 35-year-old women with a cervical venous malformation involving the masticator space. Axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted image shows a hyperintense, multilobulated mass (between the arrows) with thin internal septations. Note that the lesion permeates across tissue planes involving the masseter, parotid gland, and parapharingeal space, a characteristic feature of venous malformations

Cystic lymphangiomas (hygromas) are the most common lymphatic malformations in the neck and are usually diagnosed at birth or in the first 3 years of life. In adults these hygromas typically appear in the posterior triangle of the neck and the submandibular triangle. They appear as large multiloculated cystic masses with low density on CT and have variable signal intensity on MR depending on any haemorrhagic component or the proteinaceous content of the fluid [10]. The presence of fluid-fluid levels may occur because of non-clotting haemorrhage and suggest the diagnosis [5, 10] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

A 6-day-old baby girl with a cervical lymphangioma. Axial T2-weighted image shows a hyperintense, multilobulated, infiltrative mass involving various neck spaces, including the masseter muscle (not shown). Note the fluid-fluid level (arrow) due to intralesional haemorrhage, suggestive of the diagnosis

High-flow vascular malformations have arterial components and include arteriovenous malformations and arteriovenous fistulas. Arteriovenous malformations are common in the head and neck region and may involve the bone, more commonly the ramus and posterior body of the mandible [10, 12]. These lesions demonstrate large flow voids on T1- and T2WI on MRI because of the rapid flow within the tortuous arteries [10, 12]. When the bone is involved, it can be expanded and the lesion’s margins may appear eroded [12].

Benign lesions

Neurogenic tumours

Nerve sheath tumours are common benign tumours of the masticator space, where they arise from the mandibular nerve or its branches. Schwannoma is the most common neurogenic tumour and usually occurs along the proximal portion of the mandibular nerve, close to the foramen ovale. It appears as an oval or fusiform mass with well-defined smooth contours. On unenhanced CT the lesion has soft-tissue density while on MRI it is isointense or slightly hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI. Enhancement is usually homogeneous, although larger tumours may show heterogeneous attenuation or heterogeneous signal intensity due to cystic degeneration or haemorrhage. Atrophy and fatty infiltration of the mastication muscles are commonly seen in cases of chronic denervation [3–5] (Fig. 5).

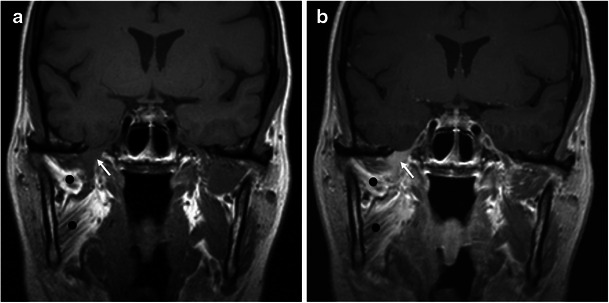

Fig. 5.

A 28-year-old man with a schwannoma of the mandibular nerve. a Precontrast and (b) postcontrast coronal T1-weighted images show a small, fusiform, homogeneously enhancing mass (arrow) at the level of the foramen ovale compatible with a schwannoma of the mandibular nerve. Also note the atrophy and fatty infiltration of the mastication muscles (black dots) due to chronic atrophy

Neurofibromas may appear as solitary or multiple lesions. When multiple, they are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [4]. Neurofibromas in NF1 may be localised or plexiform. Localised neurofibromas may demonstrate the characteristic “target sign” on T2WI with a central area of low signal intensity surrounded by a hyperintense rim [13]. Plexiform neurofibromas are diagnostic of NF1 and appear as a diffuse tortuous expansion along the branches of the parent nerve [4, 5, 13] (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A 17-year-old man with solitary and plexiform neurofibromas, diagnostic of NF1. a Axial T2-weighted MR image at the level of the masticator space shows multiple nodules, some of which (white arrow in b) show the “target appearance”—hypointense centre and hyperintense peripheral rim—suggestive of neurofibroma. The largest one is superficial to the mandibular ramus and has a heterogeneous appearance (black dot). b Coronal fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced T1WI shows tortuous expansion of small nerves in the masticator space (white arrow in b), compatible with plexiform neurofibromas

Bone lesions

Most of the mandibular lesions are odontogenic in origin [5]. Odontogenic cysts, such as dentigerous cysts or odontogenic keratocysts, are particularly common and may extend to the ramus of the mandible, causing expansion of the masticator space. Dentigerous cysts form around the crown of an unerupted tooth, most commonly the third molar, and are well-defined, unilocular, and corticated cysts [14–16]. Odontogenic keratocysts usually extend to the ramus of the mandible and may be unilocular or multilocular cystic lesions. They can also be locally aggressive, and the bone cortex may be remodelled or eroded. A high rate of recurrence is characteristic of this lesion [14–16] (Fig. 7).

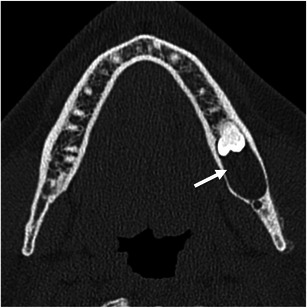

Fig. 7.

A 22-year-old man with a dentigerous cyst of the mandible. Axial unenhanced CT scan demonstrates a well-defined cystic lesion (arrow) in the posterior mandible, enveloping the crown of an unerupted mandibular third molar. Note that the mandibular cortex is intact

Ameloblastoma is a benign, locally aggressive, odontogenic tumour that usually occurs in the third molar region and extends to the mandibular ramus [16]. It can be associated with dentigerous cysts or impacted teeth. The lesion is expansile and may be unilocular or multilocular with internal septa, acquiring a “honeycomb” or “soap bubble appearance” [14, 16]. Soft-tissue components can be present and allow the distinction between this lesion and the more common odontogenic cysts [14, 16] (Fig. 8). Rarely, malignant transformation of ameloblastoma occurs [16].

Fig. 8.

A 30-year-old man with an ameloblastoma of the mandibular ramus. Axial unenhanced CT scan demonstrates an expansile lytic lesion in the left ramus of the mandible (between arrows), a typical location for ameloblastomas. This could also represent an odontogenic cyst, such as odontogenic keratocyst

Fibro-osseous lesions such as fibrous dysplasia and ossifying fibroma may involve the posterior body of the mandible or the mandibular ramus. In fibrous dysplasia the normal bone is replaced by immature bone and osteoid in a cellular fibrous matrix. It may affect one bone (monostotic) or multiple bones (polyostotic). The bone appears expanded and the density of the bone is increased, leading to the classic “ground-glass” appearance on CT [3, 14, 15]. Ossifying fibroma of the mandible is more common in the posterior region and manifests as a well-circumscribed lesion that can appear radiolucent, radiodense, or of mixed attenuation depending on the degree of calcification (Fig. 9). A peripheral “halo” of less ossified fibrous tissue, if present, is characteristic [12] (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

A 53-year-old women with craniofacial fibrous dysplasia. a Axial and (b) coronal images demonstrate expanded bone in the skull base and the left mandibular ramus (arrows) with a ground-glass appearance, characteristic of the diagnosis

Fig. 10.

A 15-year-old boy with cemento-ossifying fibroma of the mandibular ramus. a Sagittal and (b) coronal reformatted images demonstrating a well-defined expansile lesion in the mandibular ramus with internal sclerotic bands (arrow) and some ground-glass matrix

Other benign osseous lesions

Nonodotogenic cystic lesions such as simple bone cysts or aneurysmal bone cysts may occur in the masticator space. The latter usually occur in children, and the presence of fluid-fluid levels on CT or MR should suggest the diagnosis [17].

Soft tissue lesions

A variety of benign mesenchymal neoplasms (i.e., lipoma, rhabdomyoma, leiomyoma, myxoma, etc.) can occur in the soft tissues of the masticator space [3, 4, 18]. With the exception of lipomas—which show fatty attenuation on CT and follow the signal intensity of fat on MR—and the haemangioma and neurogenic tumours referred to above, the remaining lesions do not have specific imaging features.

Malignant tumours

Malignancies of the masticator space are intrinsic when they arise from the contents of the space and extrinsic when they extend from the adjacent spaces [3, 4].

Intrinsic malignancies of the space

Neurogenic tumours

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNST) are rare lesions that can arise de novo or from preexisting benign neurofibromas or schwannoma. They are commonly associated with NF1 [13, 19]. Up to 14 % of these malignant tumours occur in the head and neck region where the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve, is among the most commonly affected nerves [3, 20]. MPNSTs have similar imaging findings as schwannomas or neurofibromas. Rapid growth, extensive nerve involvement, and erosion of foramina may suggest the diagnosis [21]. Heterogeneity of the lesion, due to central necrosis or calcifications, is also more commonly associated with MPNST than with their benign counterparts [20]. However, only pathologic examination can determine the definitive diagnosis [3, 13, 19, 20].

Bone tumours

Most of the intrinsic malignancies of the masticator space are tumours of the mandible [5]. Osteosarcoma is the most common bone sarcoma and is located in the head and neck region in 10 % of the cases [22]. The most common imaging findings of osteosarcoma in the mandible include bone destruction with areas of bone sclerosis, extension to the soft tissues, and an osteoid pattern of tumour matrix mineralisation. An aggressive periosteal reaction, the “hair on end appearance”, may occur and is highly suggestive of malignancy, although not specific for osteosarcoma [22]. Periosteal osteogenic sarcomas can also arise in this region (Fig. 11).

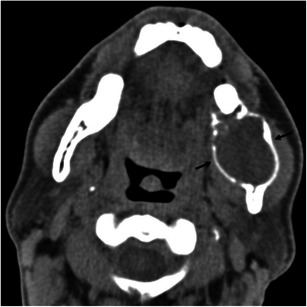

Fig. 11.

A 40-year-old women with an osteosarcoma of the mandible. a Axial and (b) reformatted sagittal contrast-enhanced CT scans show sclerotic bone lesions in the posterior left body and ramus of the mandible and an accompanying soft tissue mass (between arrows). c Axial bone window CT scan at the same level shows the exuberant spiculated periosteal reaction (black arrow)

Rarely, chondrosarcoma occurs in the mandible, near the temporomandibular joint. A soft tissue mass, with variable degrees of calcification, and erosion of the adjacent bone are the most frequent imaging findings [4]. Although it tends to be less aggressive than osteosarcoma, causing less bone destruction, the imaging distinction between the two entities is often difficult [22].

Ewing's sarcoma is the second most common primary bone malignancy in children. The posterior mandible is the most commonly involved site in the head and neck, although these tumours are rare in this region [23]. An expansile osteolytic lesion with cortical thinning and/or destruction accompanying the soft tissue mass and aggressive periosteal “onion skin” reactions are the most common imaging findings [23].

Metastatic lesions in the masticator space usually involve the posterior body and angle of the mandible and are more common than primary tumours of the mandible [5, 16]. The most common primary tumour sites include the lungs, breasts, kidneys, prostate, and thyroid [3–5, 14, 16]. The majority of secondary lesions are osteolytic, with ill-defined borders and extension into the adjacent soft tissues [16]. Osteoblastic and mixed osteolytic and osteoblastic patterns are more common in prostate and breast cancers, respectively [14]. An aggressive periosteal reaction can be present. Overall, metastatic lesions are indistinguishable from primary malignancies of the space (Fig. 12).

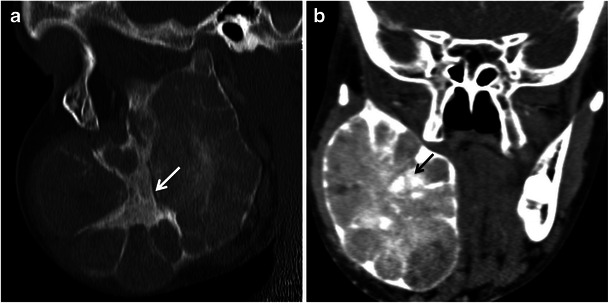

Fig. 12.

Lung cancer metastases in the masticator space. Axial (a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted MR images show a heterogeneous mass centred in the left ramus of the mandible (arrowheads) with a soft tissue component (arrows). c Axial bone window CT scan at the same level shows sclerosis of the mandibular ramus and periosteal reaction in both cortices (arrowheads), suggestive of a malignancy

Other malignant bone tumours

Rarely, malignant degeneration of amelobastoma occurs. When present, aggressive imaging features such as cortical destruction and extraosseous tumour extension may suggest the diagnosis. Multiple myeloma usually involves multiple bones, especially the angle and ramus of the mandible. Circular “punched-out” lesions are the characteristic radiographic findings. Bone reaction and bone expansion are unusual unless in association with a plasmocytoma [16].

Soft tissue tumours

A variety of soft tissue sarcomas can occur in the masticator space (i.e., rhabdomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, angiosarcoma, etc.) [3–5, 24]. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common and is generally seen in children [5]. None of these lesions have specific imaging findings, and they usually appear as infiltrative soft tissue masses associated with erosion or destruction of the bone and interruption of the involved fascia [3]. However, preservation of the involved fascia does not exclude a malignancy. For this reason, any indeterminate mass in the masticator space should prompt a biopsy [3, 25] (Fig. 13).

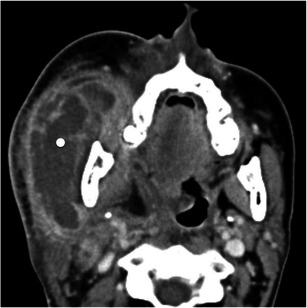

Fig. 13.

A 42-year-old man with undifferentiated sarcoma of the right masticator space. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a large mass (between arrows) in the right masticator space that invaded the ramus of the mandible. Note that despite the bone destruction, which indicates the aggressive nature of the lesion, the mass seems to be confined by the masticator fascia

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma may involve extra-nodal sites and is rarely located in the masticator space. It appears as a soft tissue mass, usually superficial, that tends to be less infiltrative than other primary tumours of the space. Additionally, bone erosion or destruction is rare. A diagnosis based on imaging findings is difficult unless other extra-nodal sites or lymph nodes are involved [3, 4, 26–28] (Fig. 14).

-

(2)

Extrinsic malignancies of the masticator space

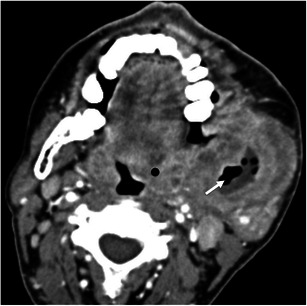

Fig. 14.

A 43-year-old women with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) involving the masticator space. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a large superficial mass centred in the masseter (white dot) corresponding to NHL. Note that the mandibular ramus is intact, which would be unusual for other soft tissue malignancies of this space. The centre of the lesion is necrotic because chemotherapy had already been started before the MR study

Extrinsic tumour involvement of the masticator space may result from direct extension of tumours from adjacent spaces or from perineural tumoral extension along the mandibular nerve or its branches.

Direct extension

Tumours from adjacent anatomical spaces may spread to the masticator space, constituting the most common malignancy of this space. Squamous cell carcinoma of the pharynx and oral cavity and malignant tumours of the parotid gland are the most common extrinsic tumours invading the masticator space [2–5].

Clinically, tumour extension to the mastication muscles is manifested by trismus. Imaging findings of extrinsic tumour involvement include effacement of the surrounding fat planes, deformity or a soft tissue mass in the space, and erosion or destruction of the mandibular ramus [2].

Nasopharyngeal carcinomas may spread through the sinus of Morgagni, a natural defect in the lateral aspect of the pharyngobasilar fascia, invading the parapharyngeal and masticator spaces [2, 29]. In more advanced cases, tumours may breach the pharyngobasilar fascia and destroy the pterygoid plates [2, 29]. Tumour involvement of the masticator space upstages and affects the overall survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma [29].

Tumours of the oral cavity, especially those of the retromolar trigone, can invade the masticator space. The retromolar trigone is a triangular-shaped area posterior to the third mandibular molar tooth covered by mucosa [30]. Beneath the mucosal surface of the retromolar trigone lies the pterygomandibular raphe, a thick fascial band where the buccinator and the superior constrictor muscles attach. It extends between the hamulus of the medial pterygoid plate and the posterior border of the mylohyoid ridge of the mandible [2, 15, 30]. Primary or secondary tumour involvement of the retromolar trigone may extend along the pterygomandibular raphe and access the masticator space, which is posterior and lateral to the raphe [2, 5, 30]. Alternatively, tumours of the oral cavity may directly invade the mandible and spread along the bone into the masticator space (Fig. 15). In this case the surrounding fascia may be intact.

Fig. 15.

A 65-year-old man with a right retromolar trigone carcinoma invading the masticator space. Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows a mass in the right retromolar trigone (white arrow) that invades the medial pterygoid muscle, which is enlarged, posteriorly (black arrows). Also note the heterogeneous attenuation of the muscle when compared to the left medial pterygoid muscle

Tumours of the oropharynx, especially those from the tonsillar region, may spread laterally through the pharyngeal wall to the parapharyngeal and masticator spaces. They may also reach the pterygomandibular raphe through the superior constrictor of the pharynx and then spread to the masticator space (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16.

A 53-year-old men with a carcinoma of the oropharynx invading the masticator space. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a left oropharyngeal mass (black dot) that extends through the parapharyngeal space into the left masticator space with extensive destruction of the mandibular ramus (white arrow)

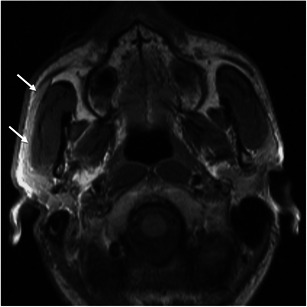

The parotid gland lies posteriorly and laterally to the masticator space. Due to this close anatomic relation, malignant tumours of the parotid gland may invade the masticator space. Infiltration of the mastication muscles and mandibular ramus are the most common imaging findings and are more common in high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma [3, 31] (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

A 40-year-old man with mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland invading the masticator space. Axial T2-weighted MR imaging shows a heterogeneous parotid mass invading the masseter (white arrow) and extending to the prestyloid compartment of the parapharyngeal space (black dot), displacing the medial pterygoid muscle anteriorly (black arrow)

Perineural tumour spread in the masticator space

Head and neck malignancies may spread along the neural sheath, a phenomenon known as perineural tumour spread (PNS). The trigeminal (V) and the facial (VII) nerves are the most frequently involved cranial nerves [32, 33].

Primary or secondary tumour extension to the masticator space may extend intracranially along the mandibular nerve through the foramen ovale. Less commonly, PNS can occur in an anterograde direction. Neuralgia of the lower face and lower jaw and weakness of the mastication muscles are the most common symptoms associated with tumour involvement of the mandibular nerve.

On CT, the imaging findings suggestive of PNS include widening or destruction of the neural foramina and/or canals and excessive enhancement of the nerve [32]. MRI is superior to CT in displaying PNS. It better depicts enlargement and increased enhancement of the involved nerve, the loss of the normal fat pad adjacent to a foramen, and enhancement and fullness of the cavernous sinus or Meckel’s cave, indicating an intracranial extension of the tumour [6, 32, 34, 35]. Indirect findings of PNS include atrophy and fatty infiltration of the mastication muscles, the mylohyoid, and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle due to chronic denervation [32].

Although tumours in any location innervated by the mandibular nerve (V3) may show retrograde PNS to the main trunk of the nerve, the auriculotemporal nerve and the inferior alveolar nerve are the most commonly involved branches [32].

The auriculotemporal nerve arises from V3 immediately below the foramen ovale. It provides cutaneous innervation to the lateral and upper face. Some of its terminal branches communicate with the facial nerve within the parotid gland, where it supplies parasympathetic innervation to the gland. For this reason, along with tumours of the lateral face, malignant parotid tumours may show retrograde perineural tumour spread to the masticator space [3, 36].

The inferior alveolar nerve provides sensory innervation to the chin, lower lip, mandibular teeth, and gingival mucosa. It enters into the mandible through the mandibular foramen at the medial surface of the mandibular ramus and terminates as the mental nerve, which exits the mental foramen in the anterior mandibular body. Thus, a skin cancer of the lower lip or chin may spread through the inferior alveolar nerve to the main trunk of the mandibular nerve [3, 33] (Fig. 18).

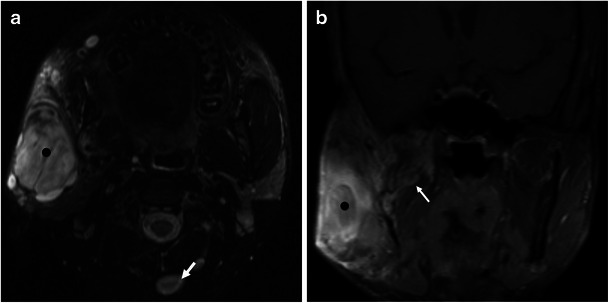

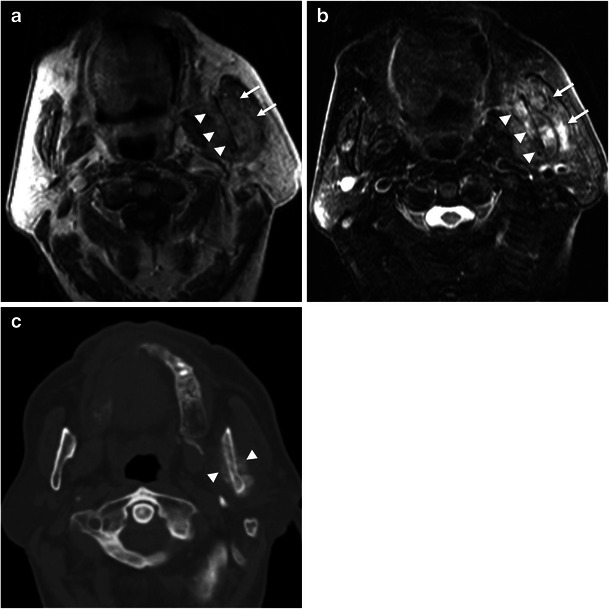

Fig. 18.

A 54-year-old man with a recurrent lower lip squamous cell carcinoma with perineural tumour spread along the inferior alveolar nerve. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan and (b) reformatted coronal bone window CT image show an enhancing subcutaneous nodule (white arrow in a) in the lower lip that appeared 2 years after the removal of a squamous cell carcinoma in this region. The relapsing tumour spread through the inferior alveolar nerve, causing widening of the inferior alveolar canal (black arrow in a), and through the mandibular nerve, causing widening of the foramen ovale (arrow in b)

Pseudolesions

Benign masticator muscle hypertrophy usually affects the masseter and is an idiopathic homogeneous enlargement of this muscle. Less frequently, the other mastication muscles are affected. On imaging studies the muscle(s) appear enlarged, with smooth margins and preservation of surrounding fascial planes. The imaging appearance of the muscles is similar to that of other normal muscles and no focal masses are defined [3, 4].

Accessory parotid tissue along the course of Stensen’s duct, over the masseter, occurs in up to 20 % of the population and may mimic a mass on clinical examination. Imaging studies clearly demonstrate the normal-appearing parotid tissue superficially overlying the masseter muscle [4] (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19.

A 20-year-old man with accessory parotid tissue. Axial T1-weighted MR image shows unilateral accessory parotid tissue overlying the right masseter (arrows) in a patient complaining of facial asymmetry. Note the asymmetry when compared to the left side

Neoplastic involvement of the mandibular nerve or its branches may cause denervation of the mastication muscles. In the acute (less than 1 month) and subacute (1 to 20 months) phases of denervation, there is enlargement and increased contrast enhancement of the muscles similar to inflammation. This can also be misinterpreted as tumour infiltration or inflammation. Clinical examination allows making the distinction: while acute denervation causes weakness of the mastication muscles, tumour infiltration manifests clinically with trismus [3, 4, 32].

Conclusion

CT and MR are essential in the diagnosis and characterisation of masticator space masses. Malignant tumours of the space may appear well defined and confined by the fascia. Thus, when a mass in the MS is identified, a biopsy should be done promptly. PNS through the mandibular nerve and its branches may occur in tumours involving the MS and recognising it is essential to plan the appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgements

This article was based on an education exhibit presented at the RSNA 97th Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting, 2011.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this work.

References

- 1.Galli F, Flor N, Villa C, Franceschelli G, Pompili G, Felisati G, Biglioli F, Cornalba GP. The masticator space. Value of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in localisation and characterisation of lesions. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010;30(2):94–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei Y, Xiao J, Zou L. Masticator space: CT and MRI of secondary tumor spread. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(2):488–497. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Som PM, Curtin HD. Parapharyngeal and masticator space lesions. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1954–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nour SG, Lewin JS (2005) Parapharyngeal and masticator spaces. In: Mafee MF, Valvassori GE, Becker M (eds) Imaging of the head and neck, 2nd ed. Thieme, New York, pp 580–624

- 5.Yousem DM, Grossman RI. Neuroradiology: the requisites. 3. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldemeyer KS, Mathews VP, Righi PD, Smith RR. Imaging features and clinical significance of perineural spread or extension of head and neck tumors. Radiographics. 1998;18(1):97–110. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.18.1.9460111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang P, Yang J, Yu Q, Ai S, Zhu W. Evaluation of solid lesions affecting masticator space with diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(6):900–907. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Q, Yang J, Wang P. Malignant tumors and chronic infections in the masticator space: preliminary assessment with in vivo single-voxel 1H-MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(4):716–719. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schuknecht B, Stergiou G, Graetz K. Masticator space abscess derived from odontogenic infection: imaging manifestation and pathways of extension depicted by CT and MR in 30 patients. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(9):1972–1979. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Som PM, Smoker WRK, Curtin HD, Reidenberg JS, Laitman J. Congenital lesions. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1828–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donnelly LF, Adams DM, Bisset GS. Vascular malformations and hemangiomas: a practical approach in a multidisciplinary clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174(3):597–608. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.3.1740597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholl RJ, Kellett HM, Neumann DP, Lurie AG. Cysts and cystic lesions of the mandible: clinical and radiologic-histopathologic review. Radiographics. 1999;19(5):1107–1124. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.5.g99se021107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banks KP. The target sign: extremity. Radiology. 2005;234:899–900. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343030946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber AL, Kaneda T, Scrivani SJ. Cysts, tumors, and nontumorous lesions of the jaw. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 930–994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smoker WRK. The oral cavity. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 1377–1464. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunfee BL, Sakai O, Pistey R, Gohel A. Radiologic and pathologic characteristics of benign and malignant lesions of the mandible. Radiographics. 2006;26(6):1751–1768. doi: 10.1148/rg.266055189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Möller B, Claviez A, Moritz JD, Leuschner I, Wiltfang J. Extensive aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(3):841–844. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31820f3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi MR, Tang YM, Panizza B (2007) Myxoma of the masticator space. Australas Radiol. pp 202–4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Lin J, Martel W. Cross-sectional imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: characteristic signs on CT, MR imaging, and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176(1):75–82. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabay JE, Collignon J, Dondelinger RF, Lens V. Neurosarcoma of the face: MRI. Neuroradiology. 1997;39(10):747–750. doi: 10.1007/s002340050500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone JA, Cooper H, Castillo M, Mukherji SK. Malignant Schwannoma of the trigeminal nerve. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(3):505–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YY, Van Tassel P, Nauert C, Raymond AK, Edeiken J. Craniofacial osteosarcomas: plain film, CT, and MR findings in 46 cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150(6):1397–1402. doi: 10.2214/ajr.150.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes SL, Almeida SM, Costa AL, Zanardi VA, Cendes F. Imaging findings of Ewing’s sarcoma in the mandible. J Oral Sci. 2007;49(2):167–171. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandez Dominguez M, Sanchez Sanchez R, Sainz Gonzalez F, Reina Perticone MA, Martinez Gonzalez JM, Mancha de la Plata M. Synovial sarcoma of the masticator space: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(11):482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Som PM, Curtin HD, Silvers AR. A re-evaluation of imaging criteria to assess aggressive masticator space tumors. Head Neck. 1997;19(4):335–341. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199707)19:4<335::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chong J, Som PM, Silvers AR, Dalton JF. Extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma involving the muscles of mastication. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19(10):1849–1851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Som PM, Braun IF, Shapiro MD, Reede DL, Curtin HD, Zimmerman RA. Tumors of the parapharyngeal space and upper neck: MR imaging characteristics. Radiology. 1987;164(3):823–829. doi: 10.1148/radiology.164.3.3039571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connor SE, Chavda SV, West R. Recurrence of Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma isolated to the right masticator and left psoas muscles. Eur Radiol. 2000;10(5):841–843. doi: 10.1007/s003300051015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel Khalek Abdel Razek A, King A. MRI and CT of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(1):11–18. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trotta BM, Pease CS, Rasamny JJ, Raghavan P, Mukherjee S. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: key imaging findings for staging and treatment planning. Radiographics. 2011;31(2):339–354. doi: 10.1148/rg.312105107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yousem DM, Kraut MA, Chalian AA. Major salivary gland imaging. Radiology. 2000;216(1):19–29. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsberg L. Imaging of perineural tumor spread in head and neck cancer. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and neck imaging. 4. St Louis: Mosby; 2003. pp. 865–885. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker GD, Harnsberger HR. Clinical-radiologic issues in perineural tumor spread of malignant diseases of the extracranial head and neck. Radiographics. 1991;11(3):383–399. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.3.1852933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matzko J, Becker DG, Phillips CD. Obliteration of fat planes by perineural spread of squamous cell carcinoma along the inferior alveolar nerve. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1843–1845. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laine FJ, Braun IF, Jensen ME, Nadel L, Som PM. Perineural tumor extension through the foramen ovale: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1990;174(1):65–71. doi: 10.1148/radiology.174.1.2152985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmalfuss IM, Tart RP, Mukherji S, Mancuso AA. Perineural tumor spread along the auriculotemporal nerve. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(2):303–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]