Abstract

Background

Recent studies identify a survival benefit from the administration of antifibrinolytic agents in severely injured trauma patients. However, identification of hyperfibrinolysis requires thromboelastometry, which is not widely available. We hypothesized that analysis of patients with thromboelastometry-diagnosed hyperfibrinolysis would identify clinical criteria for empiric antifibrinolytic treatment in the absence of thromboelastometry.

Methods

From 11/2010 – 3/2012, serial blood samples were collected from 115 critically-injured patients on arrival to the emergency department of an urban level I trauma center. Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) was performed to assess viscoelastic properties of clot formation in the presence and absence of aprotinin to identify treatable hyperfibrinolysis. In 20 patients identified with treatable hyperfibrinolysis, clinical predictors were investigated using receiver-operator characteristic analysis.

Results

Of 115 patients evaluated, 20% had hyperfibrinolysis, defined as an admission maximal clot lysis ≥10% reversible by aprotinin treatment. Patients with hyperfibrinolysis had significantly lower temperature, pH, and platelet counts, and higher INR, PTT, and D-dimer. Hyperfibrinolysis was associated with multiorgan failure (63.2% vs. 24.6%, p=0.004) and mortality (52.2% vs. 12.9%, p<0.001). We then evaluated all non-ROTEM clinical and laboratory parameters predictive of hyperfibrinolysis using receiver-operator characteristic analysis to evaluate potential empiric treatment guidelines. The presence of hypothermia (temperature ≤36.0), acidosis (pH ≤7.2), relative coagulopathy (INR ≥1.3 or PTT ≥30), or relative thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤200) identified hyperfibrinolysis with 100% sensitivity and 55.4% specificity (area under the curve 0.777).

Conclusions

Consideration of empiric antifibrinolytic therapy is warranted for critically-injured trauma patients who present with acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy, or relative thrombocytopenia. These clinical predictors identified hyperfibrinolysis with 100% sensitivity while simultaneously eliminating 46.6% of inappropriate therapy compared to the empiric treatment of all injured patients. These criteria will facilitate empiric treatment of hyperfibrinolysis for clinicians without access to thromboelastography.

Level of evidence

Prognostic study, Level I

Keywords: Fibrinolysis, thromboelastography, rotational thromboelastometry, ROTEM

BACKGROUND

Hemorrhage remains the leading cause of potentially preventable death after trauma, exacerbated in up to a third of injured patients by abnormal coagulation that is present on arrival to the emergency department.1 This phenomenon, referred to as acute traumatic coagulopathy (ATC), exists independently of the classically identified coagulopathy risk factors of hypothermia, hemodilution, and acidosis.2 Acute traumatic coagulopathy occurs in the setting of massive tissue injury and hypoperfusion, and results in both impairment of new clot formation as well as enhanced fibrinolysis of existing clot.3, 4 While the early empiric administration of plasma5, 6 and damage control strategies7 have been shown to mitigate the effects of impaired clot formation, guidelines addressing treatment of clinically significant fibrinolysis after injury are sparse. This enhanced fibrinolysis, termed hyperfibrinolysis (HF), has been identified as an integral component of ATC. Recent intriguing data suggest that the use of plasminogen-targeted inhibitors of enzymatic fibrinolysis such as tranexamic acid (TXA) may provide the missing pharmacologic treatment for the hyperfibrinolytic component of ATC.8, 9

While several groups have reported on varying degrees of hyperfibrinolysis (HF) after injury, the precise incidence of HF remains unclear due in part to heterogeneity in diagnostic technique and lack of consensus definitions.10–13 Currently the gold standard for diagnosing HF is thromboelastometry; however, these devices are not yet widely available and protocols for their use in guiding trauma resuscitation have so far been limited to single-center experiences.14–17 The clinical relevance of treating HF is clear based on the CRASH-2 large randomized controlled trial of empiric administration of TXA in critically injured trauma patients, which identified a significant mortality benefit to empiric TXA therapy in critically injured patients.9 However, no diagnostic criteria were used to specifically identify HF prior to enrollment, suggesting that a large cohort of these patients were over-treated.

Clearly, specific identification of the patients that are at highest risk for developing HF would facilitate appropriate therapy for the hyperfibrinolytic component of ATC while avoiding the cost and potential side effects of over-treatment. Therefore, the aims of this study are: 1) to identify patients with treatable hyperfibrinolysis using thromboelastography, 2) to characterize the relationship of hyperfibrinolysis with injury characteristics and outcomes, and 3) to identify clinical- and basic laboratory value-based guidelines for appropriate empiric treatment of hyperfibrinolysis in the absence of thromboelastography.

METHODS

Blood samples were prospectively collected from 115 critically-injured trauma patients on arrival to the emergency department of an urban level I trauma center. Patients who were <18 years old, had >5% body surface area burns, received >2 liters of intravenous fluid prior to arrival, or were transferred from another institution were excluded. Admission blood samples were collected via initial placement of a 16g or larger peripheral IV into 3.2% (0.109M) sodium citrate, and processed within 3h of being drawn; sample collection methodology is described in detail elsewhere.3 After a waiver of consent was applied for initial blood draws, informed consent was obtained for all study patients as approved by our institutional Committee on Human Research.

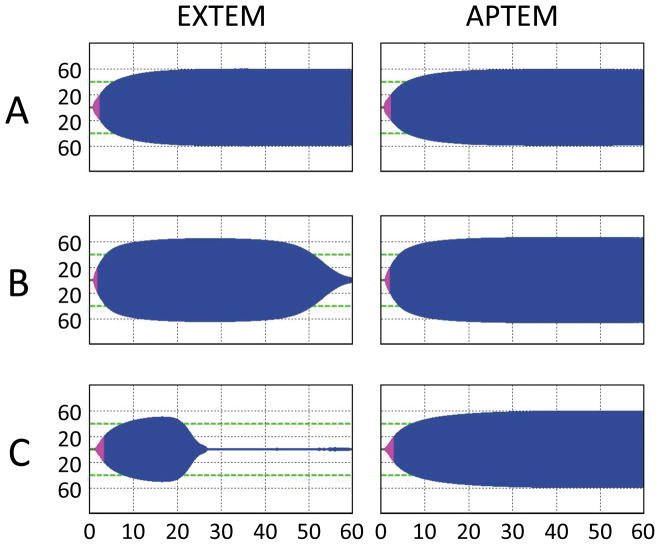

Point-of-care rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®) was performed to assess viscoelastic properties of clot formation. Briefly, 300μL samples of citrated whole blood were warmed to 37°C, recalcified, and activated with tissue factor-containing rabbit brain thromboplastin in the presence (APTEM) and absence (EXTEM) of aprotinin. An enzymatic fibrinolysis index (EFI) was defined as the difference in maximal clot lysis percentage between EXTEM and APTEM testing, identifying hyperfibrinolysis amenable to treatment and eliminating variability not related to enzymatic fibrinolysis. Massive transfusion was defined as transfusion of ≥10 units of red blood cells (RBC) within the first 24h of admission in patients surviving to 24h; to include patients who received high-volume transfusion but did not survive to 24h, scaled transfusion of ≥5 units in patients dying by 12h or ≥2.5 units in patients dying by 6h were also included. Activity levels of Factors II, V, VII, VIII, IX, and X, antithrombin III and Protein C, as well as antigen levels of fibrinogen and D-dimer levels were assayed using a Stago Compact Functional Coagulation Analyzer (Diagnostica Stago; Parsippany, NJ). Activated Protein C was assayed using an established ELISA method reported elsewhere.4 Standard laboratory, resuscitation, and outcomes data were prospectively collected in parallel.

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (inter-quartile range [IQR]), or percentage; univariate comparisons were made using Student’s t-test for normally distributed data, Wilcoxon rank-sum testing for skewed data, and Fisher’s exact test for proportions. Standard logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of hyperfibrinolysis. Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analysis and logrank testing were used to assess differences in 24-hour and in-hospital mortality between groups. Nonparametric receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to characterize the ability of clinical predictors to identify hyperfibrinolysis. An alpha of 0.05 was considered significant. All data analysis was performed by the authors using Stata version 12 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

RESULTS

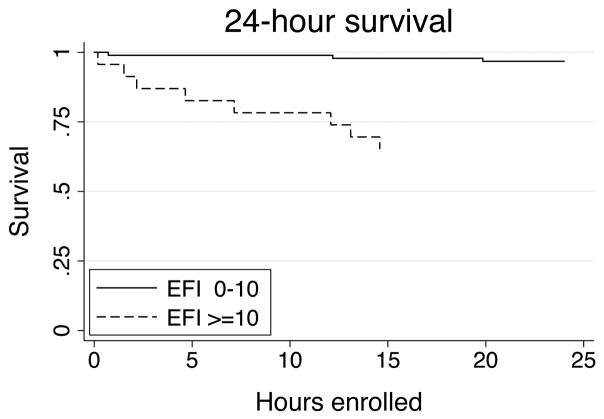

The overall study population had age 40.8±19.2y, penetrating injury in 26.1%, neurologic injury in 54.9%, ISS 22.0±14.5, base deficit −5.4±6.0, and GCS 10 (5–14). Of the 115 patients with complete ROTEM® data on admission, 23 patients (20%) had hyperfibrinolysis as defined by an admission EFI ≥10% (Table 1). Sample tracings for representative patients with hyperfibrinolysis are provided in Figure 1. In terms of clinical characteristics, patients with hyperfibrinolysis had significantly lower admission temperature, higher incidence of both early (<6h) red blood cell transfusion and massive transfusion, higher mechanical ventilation requirements, and higher incidence of multiorgan failure and mortality (Table 2). As confirmed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, patients with hyperfibrinolysis die significantly earlier and more often than those without (log-rank p<0.001; Figure 2). In terms of admission clinical laboratory values, patient with hyperfibrinolysis had significantly higher INR, PTT, and D-dimer levels (all p < 0.02; Table 3). The clotting factor and anticoagulant profile demonstrates that hyperfibrinolysis is further associated with significant depletion of Factors V and Factor IX, as well as elevation of activated Protein C (all p < 0.03; Table 3). We then evaluated all population differences with p < 0.200 using both univariate and multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of hyperfibrinolysis (Table 4). This identified lower temperature, pH, and platelet count, and higher INR, PTT, and D-dimer as significant univariate predictors of hyperfibrinolysis; however, none of these parameters alone were independent predictors of hyperfibrinolysis when adjusted for injury severity score and admission base deficit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with hyperfibrinolysis

| ID | Age | Sex | Mechanism | Injuries | EX ML | AP ML | EFI | 24h RBC | MT | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | M | Gunshot to axilla, thigh | Rib fracture, lung laceration, soft tissue injury | 13% | 2% | 11% | 1 | N | Discharged, hospital day 6 |

| 2 | 62 | M | Assault | Tracheal fracture, subgaleal hematoma | 19% | 6% | 13% | 0 | N | Discharged, hospital day 5 |

| 3 | 40 | M | 10-foot fall down stairs | Mandibular fracture, T12/L1 compression fractures, subgaleal hematoma | 28% | 15% | 13% | 0 | N | Discharged, hospital day 6 |

| 4 | 68 | F | Pedestrian vs. bicycle | Skull base fractures, SDH, SAH, carotid dissection | 20% | 6% | 14% | 2 | N | Died of hypoxia, hospital day 27 |

| 5 | 80 | F | Pedestrian vs. auto | SDH, SAH, IPH | 27% | 11% | 16% | 4 | N | Discharged, hospital day 59 |

| 6 | 19 | M | Multiplegunshots to shoulder, axilla, abdomen, back, perineum | Rib fracture, lung laceration, retroperitoneal hematoma, rectal wall hematoma | 34% | 17% | 17% | 0 | N | Discharged, hospital day 7 |

| 7 | 26 | M | 4-story fall | Facial and rib fractures; liver, splenic, renal, and pancreatic lacerations; duodenal hematoma | 37% | 16% | 21% | 14 | Y | Discharged, hospital day 28 |

| 8 | 22 | M | Pedestrian vs. auto | Skull fractures, SAH, SDH, T5 vertebral body fracture, pulmonary contusion, clavicle and scapular fractures | 36% | 12% | 24% | 2 | N | Discharged, hospital day 24 |

| 9 | 32 | M | Gunshots to chest, upper extremity | Rib fracture, hemothorax, kidney laceration, T10–11 spinal cord injury, soft tissue injury | 58% | 16% | 42% | 0 | N | Discharged, hospital day 26 |

| 10 | 23 | M | Motor vehicle collision w/ejection | Skull base fracture, SDH, SAH, facial fractures, upper extremity fracture | 54% | 9% | 45% | 14 | Y | Discharged, hospital day 32 |

| 11 | 71 | F | Blunt head injury | SDH, SAH | 95% | 12% | 83% | 8 | Y | Care withdrawn, ICU day 1 |

| 12 | 24 | M | Helmeted motorcycle crash w/ejection and 40-foot fall | Carotid disruption, SAH, C1/C2 fracture, pulmonary contusion, renal and splenic lacerations | 100% | 10% | 90% | 6 | Y | Care withdrawn, ICU day 1 |

| 13 | 52 | M | Helmeted motorcycle crash; preexisting cirrhosis | SDH, pulmonary contusion; rib, vertebral body, scapular, and clavicular fractures | 100% | 8% | 92% | 40 | Y | Care withdrawn, ICU day 10 |

| 14 | 48 | M | Fall from standing; intoxicated | SAH | 100% | 7% | 93% | 0 | N | Discharged, hospital day 3 |

| 15 | 69 | M | Hanging | Diffuse anoxic brain injury | 100% | 6% | 94% | 0 | N | Care withdrawn, ICU day 2 |

| 16 | 84 | F | 20-foot fall | Pelvic fractures, lower extremity fractures | 100% | 5% | 95% | 9 | Y | Died of cardiac arrest, day 1 |

| 17 | 37 | M | Gunshot to head | SAH, cerebral edema, uncal herniation | 100% | 4% | 96% | 2 | N | Care withdrawn, ICU day 1 |

| 18 | 22 | M | Gunshot to head | SAH, SDH | 99% | 3% | 96% | 0 | N | Care withdrawn, ICU day 1 |

| 19 | 35 | M | Stab wound to neck | Tracheal disruption, traumatic arrest requiring emergency thoracotomy | 99% | 2% | 97% | 2 | Y | Died of cardiac arrest, day 1 |

| 20 | 56 | M | 20-step fall | EDH, SDH, SAH | 99% | 2% | 97% | 5 | N | Discharged, hospital day 6 |

| 21 | 25 | F | Bicycle vs. auto | SAH, carotid artery dissection, sternal fracture, lung laceration, liver laceration, pelvic fractures | 99% | 2% | 97% | 13 | Y | Care withdrawn, ICU day 1 |

| 22 | 74 | F | Fall from standing; preexisting cirrhosis | Humerus fracture, femoral arterial injury | 100% | 0% | 100% | 56 | Y | Died of hemorrhage, day 1 |

| 23 | 85 | M | Fall from standing | SAH, SDH | 100% | 0% | 100% | 0 | N | Died of multiorgan failure, ICU day 7 |

Demographic and injury characteristics of patients with hyperfibrinolysis. SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage, SDH = subdural hemorrhage, IPH = intraparenchymal hemorrhage, EDH = epidural hematoma, EX ML = EXTEM maximum lysis, AP ML = APTEM maximum lysis, EFI = enzymatic fibrinolysis index, RBC = red blood cell units transfused over first 24h, MT = massive transfusion.

Figure 1.

Representative admission ROTEM® tracings for patients with hyperfibrinolysis.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics by hyperfibrinolysis

| HFI >=10 (N=23) | HFI 0–10 (N=92) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.2 ± 22.6 | 39.2 ± 18.1 | 0.125 |

| Penetrating injury | 26.1% | 26.1% | 1.000 |

| Neurologic injury | 60.9% | 53.3% | 0.640 |

| ISS | 23.0 ± 13.2 | 21.8 ± 14.8 | 0.767 |

| GCS | 9 (3–14) | 10 (6–14) | 0.304 |

| Temperature | 35.4 ± 0.8 | 36.1 ± 0.6 | 0.012* |

| Prehospital IVF | 150 (50–250) | 225 (0–1000) | 0.988 |

| Transfused RBC in 6h | 60.9% | 33.8% | 0.029* |

| Massively transfused | 39.1% | 5.5% | <0.001* |

| Hospital days | 6 (1–25) | 10 (4–18) | 0.073 |

| ICU days | 2 (1–11) | 4 (2–12.5) | 0.119 |

| Vent-free days/28d | 2 (0–25) | 25 (10.5–27) | 0.004* |

| Multiorgan failure | 63.2% | 24.6% | 0.004* |

| 24h mortality | 34.8% | 3.5% | <0.001* |

| In-hospital mortality | 52.2% | 12.9% | <0.001* |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). BMI = body mass index, ISS = injury severity score, GCS = Glasgow coma score, IVF = intravenous fluid, RBC = red blood cell units, ICU = intensive care unit, EFI = enzymatic hyperfibrinolysis index.

p < 0.05 by Student’s t, Mann-Whitney, or Fisher’s exact testing.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier 24-hour survival curves showing early survival differences between patients with (dashed line) and without (solid line) hyperfibrinolysis. *p < 0.001 by log-ran test.

Table 3.

Admission laboratory values by hyperfibrinolysis

| EFI >=10 (N=23) | EFI 0–10 (N=85) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| INR | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | <0.001* |

| PTT | 32.0 (28.0–41.9) | 27.0 (24.6–30.0) | <0.001* |

| pH | 7.17 ± 0.17 | 7.29 ± 0.15 | 0.035* |

| Base deficit | −7.3 ± 5.4 | −4.7 ± 6.2 | 0.109 |

| Hematocrit | 39.1 ± 6.2 | 40.6 ± 5.8 | 0.302 |

| Platelet count | 238 ± 82 | 278 ± 76 | 0.043* |

| Fibrinogen | 164 ± 89 | 292 ± 164 | 0.116 |

| D-dimer | 7.8 (5.7–9.2) | 1.8 (0.6–8.1) | 0.019* |

| Factor II | 65.2 ± 22.2 | 70.4 ± 18.0 | 0.415 |

| Factor V | 27.1 ± 16.8 | 45.7 ± 25.3 | 0.005* |

| Factor VII | 88.1 ± 33.9 | 89.1 ± 47.7 | 0.927 |

| Factor VIII | 173.3 ± 93.1 | 188.6 ± 109.3 | 0.626 |

| Factor IX | 92.7 ± 46.0 | 132.2 ± 54.2 | 0.011* |

| Factor X | 72.2 ± 26.7 | 75.3 ± 21.8 | 0.690 |

| AT3 | 75.2 ± 31.2 | 80.5 ± 23.9 | 0.574 |

| PC | 105.7 ± 46.6 | 89.9 ± 34.8 | 0.266 |

| aPC | 25.5 (10.7–51.5) | 3.2 (2.1–15.1) | 0.028* |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). INR = international normalized ratio, PTT = activated partial thromboplastin time, aPC=activated Protein C, EFI = enzymatic hyperfibrinolysis index.

p < 0.05 by Student’s t, Mann-Whitney, or Fisher’s exact testing.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate predictors of hyperfibrinolysis

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | P-value | Odds Ratio | P-value | |

| Age | 1.021 | 0.077 | 1.027 | 0.201 |

| Temperature | 0.229 | 0.006* | 0.233 | 0.078 |

| INR | 1.332 | 0.007* | 1.177 | 0.135 |

| PTT | 1.125 | 0.002* | 1.099 | 0.055* |

| pH | 0.633 | 0.036* | 0.781 | 0.722 |

| Base deficit | 0.931 | 0.131 | 0.913 | 0.126 |

| Platelet count | 0.993 | 0.034* | 0.990 | 0.075 |

| Fibrinogen | 0.987 | 0.109 | 0.969 | 0.207 |

| D-dimer | 1.238 | 0.018* | 1.345 | 0.057 |

Logistic regression was used to generate both unadjusted univariate odds ratios as well as multivariate, ISS and base deficit-adjusted odds ratios for hyperfibrinolysis. GCS = Glasgowcoma score, INR = international normalized ratio, PTT = activated partial thromboplastin time. Odds ratios for INR and pH scaled for differences of 0.1.

p < 0.05 by Wald test.

As no individual non-ROTEM® parameters independently predicted hyperfibrinolysis, we then evaluated combinations of univariate predictors of hyperfibrinolysis using ROC analysis to identify potential empiric treatment guidelines. To identify broad guidelines, we included only univariate predictors that are widely available as part of a standard trauma clinical and laboratory work-up as candidates, excluding specialized clotting factor measurements, fibrinogen, and D-dimer levels. For continuous values, we selected cut-offs at the value yielding the highest percentage of patients correctly classified as having hyperfibrinolysis or not. Using these pooled cut-offs, the presence of hypothermia (temperature ≤36.0), acidosis (pH ≤7.2), relative coagulopathy (INR ≥1.3 or PTT ≥30), or relative thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤200) identified hyperfibrinolysis with 100% sensitivity, 55.4% specificity, and positive likelihood ratio 2.24 (area under the curve 0.777; 95% confidence interval [0.726 – 0.828]).

In order to avoid the inclusion of moribund patients in whom empiric treatment of hyperfibrinolysis would be futile, we repeated all previous analysis excluding patients in whom care was withdrawn as a surrogate for nonsurvivable injury. Seventeen patients met these criteria (Table 1). When excluding these patients, mortality remained significantly worse in patients with hyperfibrinolysis (p=0.006). In univariate analysis for predictors of hyperfibrinolysis, INR (p=0.062), pH (p=0.093), platelet count (p=0.136), and D-dimer (p=0.055) were no longer significant, while temperature and PTT remained predictive (p<0.05). Excluding nonsurvivably injured patients, the previously identified criteria for empiric treatment remained 100% sensitive for hyperfibrinolysis, with slightly improved specificity (59.0% specificity, positive likelihood ratio 2.44) and a similar and still significant area under the ROC curve of 0.795 (95% confidence interval: 0.742 – 0.848).

DISCUSSION

While intriguing data exist regarding a survival benefit to the pharmacologic treatment of hyperfibrinolysis after trauma, broad clinical application of this knowledge has been impaired by a lack of specific diagnostic criteria and the absence of guidelines for empiric therapy. Several recent single-center studies have investigated hyperfibrinolysis after trauma using thromboelastography; however, heterogeneity in study populations, enrollment criteria, thromboelastography assays, and viscoelastic parameters assessed has led to variable estimates of the incidence of hyperfibrinolysis, ranging from 3 to 20% of all trauma patients.13 Despite significant uncertainty regarding the incidence, there is no clinical disagreement that hyperfibrinolysis portends a markedly worse prognosis, with the same studies identifying mortality rates of 38.5% to 100% in patients with hyperfibrinolysis. The data presented here add significantly to this growing body of knowledge in terms of diagnostic utility, patient-level characterization, and clinically applicable guidelines for empiric treatment.

Two commercially available systems exist for thromboelastography: ROTEM® and TEG®. Two studies use TEG-based diagnostic criteria to identify hyperfibrinolysis, using a 15% decrement in clot firmness either 3010 or 6018 minutes after maximal clot amplitude. Similar results have been published by several groups using comparable ROTEM-based maximal clot lysis parameters.12, 19–21 Using ROTEM APTEM test-based criteria provides the additional theoretical advantage of identifying only fibrinolysis that is reversible by treatment with aprotinin, thereby eliminating spurious clot amplitude reduction due to sample drying and clot retraction while simultaneously providing a gauge of potential treatment efficacy. To our knowledge, only one other group has published data using an APTEM-based definition; this study by Levrat and colleagues identified hyperfibrinolysis in 87 trauma patients admitted to a large academic trauma center in France, identifying 6 patients (5%) with a >7% increase in maximal clot firmness between EXTEM and APTEM-activated samples.11 Here we use a similar definition, identifying 15 patients (20%) with a >10% enzymatic fibrinolysis index; both studies identify significant associations between hyperfibrinolysis and increased injury severity, coagulopathy, and increased mortality.

We further extend this analysis by identifying hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy, and relative thrombocytopenia as predictors of hyperfibrinolysis in univariate analysis. Of the other studies addressing hyperfibrinolysis after trauma, only that of Kashuk and colleagues systematically investigated adjusted predictors of hyperfibrinolysis in their cohort of 11 patients with TEG-based hyperfibrinolysis out of 61 trauma patients receiving transfusions.10 Both our study as well as that of Kashuk et al. identified elevated emergency department coagulopathy as a critical predictor of hyperfibrinolysis. We further identify significant depletion of Factor V and Factor IX, as well as elevation of activated Protein C, in patients with hyperfibrinolysis. Taken together, the clear clinical relationship between impairment of clot formation and activation of fibrinolysis lends credence to the recently described dual role of the activated Protein C system in coagulopathy after trauma via cleavage of activated Factors Va and VIIIa as well as derepression of fibrinolysis.3, 4

The recent prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled CRASH-2 trial evaluated over 20,000 trauma patients in a large placebo controlled trial and identified a significant decrease in both all-cause (14.5% vs 16.0%) and hemorrhage-related (4.9% vs 5.7%) mortality in trauma patients treated empirically with TXA.9 However, inclusion criteria for the study were broad, with only half of enrolled patients receiving a blood transfusion or requiring an emergency operation. Based on the 1.5% absolute mortality risk reduction identified, the number needed to treat empirically with TXA in order to save one life is 67; this modest risk reduction observed likely reflects significant overtreatment. These generalizability concerns are partially addressed by the recent Military Application of Tranexamic acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) study, which retrospectively evaluated the use of TXA in 293 of 896 combat injured patients with respect to total blood product use, thromboembolic complications, and mortality.8 Theauthors found that the TXA-treated group had lower unadjusted mortality than the non-TXA-treated group (17.4% vs 23.9%, respectively, with an absolute mortality risk reduction of 6.5%) despite more severe injury. Notably, the rate of thromboembolic complications was significantly greater in the TXA-treated compared with non-TXA-treated group in this study. Although TXA treatment was not an independent predictor of thromboembolism in adjusted analysis performed in the MATTERs study and the incidence of thromboembolic complications did not significantly differ between TXA-and placebo-treated patients in the CRASH-2 trial, this highlights the important concern of potentially increased thromboembolic risk with TXA treatment. In the more selective TXA treatment assessed in the MATTERs study compared to that of CRASH-2, the overall number needed to treat in order to save one life is 15; this is further reduced to as low as 7 in patients requiring massive transfusion (absolute risk reduction: 13.7%). Overall, available evidence indicates that a subset of trauma patients exist in whom empiric TXA treatment would provide a significant survival benefit while minimizing treatment cost and the risk of side effects.

The data presented here provide a first attempt to specifically address this critical gap in the growing literature on the management of hyperfibrinolysis after trauma by outlining criteria for empiric antifibrinolytic treatment. Specifically, we provide data that treatment of any critically-injured patient with hypothermia (temperature ≤36.0), acidosis (pH ≤7.2), relative coagulopathy (INR ≥1.3 or PTT ≥30), or relative thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤200) would identify hyperfibrinolysis with 100% sensitivity and 55.4% specificity. Furthermore, data from both the MATTERs study as well as Kashuk and colleagues highlight the increased incidence of hyperfibrinolysis in patients receiving massive transfusions. Specifically, the MATTERs study identified an enhanced absolute mortality risk reduction associated with TXA treatment of 13.7% in patients requiring massive transfusion compared to 6.5% in the overall study population.8 Similarly, Kashuk et al. show that 34% of patients requiring >6 units of red blood cells within 6h of admission had TEG-based hyperfibrinolysis compared to 18% of patients overall, suggesting that patients requiring massive transfusion are at higher risk of hyperfibrinolysis. In our patient population, transfusion of RBC within 6h of admission was significantly more common, and massive transfusion within the first 24h more than seven-fold more common, in patients with hyperfibrinolysis. Taking these data together, we would advocate that any patient with clinically significant injury presenting with acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy, or relative thrombocytopenia should be considered for empiric treatment with an antifibrinolytic agent within 1h of arrival, and that empiric early antifibrinolytic therapy should be considered as an addition to institutional massive transfusion protocols.

As with the other currently available studies of hyperfibrinolysis after trauma, several limitations are important in the interpretation of the results presented here. With 115 patients available for analysis, sample size limits both the generalizability as well as the statistical power of this study, highlighting the need for further prospective, multicenter evaluation of both diagnostic criteria as well as treatment protocols for hyperfibrinolysis prior to their widespread adoption. Although thromboelastography is the current de facto gold standard for the diagnosis of hyperfibrinolysis, the significant heterogeneity of findings using several biochemical markers of fibrinolysis has made specific validation of functional testing such as ROTEM- and TEG-based thromboelastography elusive. Addressing this technical concern, Levrat and colleagues have previously validated the ROTEM EXTEM and APTEM tests in a cohort of 23 patients using a euglobin clot lysis time <90min as a gold standard, showing 100% specificity of ROTEM in the diagnosis of hyperfibrinolysis.11 Furthermore, the enzymatic hyperfibrinolysis index defined here in relies on the ROTEM APTEM maximal clotting firmness, using the requirement of reversibility by aprotinin to eliminate spurious results due to mechanical clot retraction and confounding by other factors unrelated to true enzymatic fibrinolysis. The release of tissue thromboplastins leading to local hypercoagulability and systemic DIC-like consumptive coagulopathy has been posited to underlie coagulopathy in severe traumatic brain injury, although this mechanism remains poorly understood. While reversal of hyperfibrinolytic coagulopathy may mitigate the threat of progressive hematoma enlargement and herniation in the setting of active intracranial hemorrhage, this must be balanced with the theoretical risk of worsening ischemic damage in the penumbra of injury. Furthermore, the CRASH-2 trial did not demonstrate a mortality reduction in head injury-related death in the TXA-treated group compared to placebo,9 and the MATTERs study found that admission GCS ≤8 was an independent predictor of mortality, even when adjusted for TXA treatment.8 Taken together, these results imply that antifibrinolytic therapy may be less efficacious in this group. As with all empiric guidelines, clinical judgment must balance the potential risks and benefits of treatment given the clinical uncertainty that remains in select settings such as traumatic brain injury. Finally, although both aprotinin and tranexamic acid bind and inhibit plasmin, differences in the specificity of the bovine-derived polypeptide aprotinin and the synthetic lysine analogue tranexamic acid exist, and their efficacy in reversal of fibrinolysis may not be equivalent;22 therefore, inferences about the potential efficacy of tranexamic acid presented here should be interpreted with caution.

Overall, this study confirms and extends the growing body of literature on the recognition and treatment of hyperfibrinolysis after trauma through specific thromboelastography-based diagnostic criteria, multivariate risk factor assessment, and receiver operator characteristic-based clinical guidelines for empiric treatment. These data highlight the clinical utility of thromboelastography, and confirm a mechanistic link between acute traumatic coagulopathy and hyperfibrinolysis. Most importantly, data presented here support the empiric treatment of fibrinolysis in trauma patients who present with acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy, and relative thrombocytopenia as a strategy for appropriately sensitive empiric treatment in clinical settings in which thromboelastography and other advanced diagnostic equipment is unavailable.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by NIH T32 GM-08258-20 (MEK), NIH GM-085689 (MJC)Stata version 12 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

The authors acknowledge technical support from the ROTEM® instrument distributor (Tem Innovations GmbH (formerly Pentapharm); Munich, Germany) and the helpful technical assistance of Pamela Rahn

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The ROTEM® device was loaned and reagents provided by the distributor (Tem Innovations GmbH (formerly Pentapharm); Munich, Germany) for this investigator-initiated study. There are no direct financial relationships between the authors and manufacturer.

Meetings: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MEK, MWC, and MJC prepared the manuscript, performed all data analysis, and take full responsibility for the data as presented. RCM, IMC, MDG, and LAC performed clinical data collection. BJR and MFN made significant contributions to study design and implementation.

Contributor Information

Matthew E Kutcher, Email: matthew.kutcher@ucsfmedctr.org.

Michael W Cripps, Email: michael.cripps@ucsfmedctr.org.

Ryan C McCreery, Email: mccreeryr@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Ian M Crane, Email: cranei@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Molly D Greenberg, Email: greenbergm@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Leslie M Cachola, Email: cacholal@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Brittney J Redick, Email: redickb@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Mary F Nelson, Email: nelsonm@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

Mitchell Jay Cohen, Email: mcohen@sfghsurg.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Hess JR, Brohi K, Dutton RP, et al. The coagulopathy of trauma: a review of mechanisms. J Trauma. 2008;65(4):748–54. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181877a9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Davenport RA. Acute coagulopathy of trauma: mechanism, identification and effect. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(6):680–5. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1e78f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brohi K, Cohen MJ, Ganter MT, et al. Acute traumatic coagulopathy: initiated by hypoperfusion: modulated through the protein C pathway? Ann Surg. 2007;245(5):812–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000256862.79374.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen MJ, Call M, Nelson M, et al. Critical Role of Activated Protein C in Early Coagulopathy and Later Organ Failure, Infection and Death in Trauma Patients. Ann Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318235d9e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holcomb JB, Wade CE, Michalek JE, et al. Increased plasma and platelet to red blood cell ratios improves outcome in 466 massively transfused civilian trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):447–58. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a9ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinella PC, Perkins JG, Grathwohl KW, et al. Effect of plasma and red blood cell transfusions on survival in patients with combat related traumatic injuries. J Trauma. 2008;64(2 Suppl):S69–77. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318160ba2f. discussion S77–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duchesne JC, Kimonis K, Marr AB, et al. Damage control resuscitation in combination with damage control laparotomy: a survival advantage. J Trauma. 2010;69(1):46–52. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181df91fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison JJ, Dubose JJ, Rasmussen TE, et al. Military Application of Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Emergency Resuscitation (MATTERs) Study. Arch Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakur H, Roberts I, Bautista R, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):23–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Sawyer M, et al. Primary fibrinolysis is integral in the pathogenesis of the acute coagulopathy of trauma. Ann Surg. 2010;252(3):434–42. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f09191. discussion 443–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levrat A, Gros A, Rugeri L, et al. Evaluation of rotation thrombelastography for the diagnosis of hyperfibrinolysis in trauma patients. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(6):792–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schochl H, Frietsch T, Pavelka M, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis after major trauma: differential diagnosis of lysis patterns and prognostic value of thrombelastometry. J Trauma. 2009;67(1):125–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818b2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schochl H, Voelckel W, Maegele M, et al. Trauma-associated hyperfibrinolysis. Hamostaseologie. 2012;32(1):22–7. doi: 10.5482/ha-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez E, Pieracci FM, Moore EE, et al. Coagulation abnormalities in the trauma patient: the role of point-of-care thromboelastography. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36(7):723–37. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1265289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson PI, Stissing T, Bochsen L, et al. Thrombelastography and tromboelastometry in assessing coagulopathy in trauma. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2009;17:45. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-17-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Sawyer M, et al. Postinjury coagulopathy management: goal directed resuscitation via POC thrombelastography. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):604–14. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3599c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kashuk JL, Moore EE, Wohlauer M, et al. Initial experiences with point-of-care rapid thrombelastography for management of life-threatening postinjury coagulopathy. Transfusion. 2012;52(1):23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll RC, Craft RM, Langdon RJ, et al. Early evaluation of acute traumatic coagulopathy by thrombelastography. Transl Res. 2009;154(1):34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schochl H, Solomon C, Traintinger S, et al. Thromboelastometric (ROTEM) findings in patients suffering from isolated severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(10):2033–41. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tauber H, Innerhofer P, Breitkopf R, et al. Prevalence and impact of abnormal ROTEM(R) assays in severe blunt trauma: results of the ‘Diagnosis and Treatment of Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy (DIA-TRE-TIC) study’. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(3):378–87. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theusinger OM, Wanner GA, Emmert MY, et al. Hyperfibrinolysis diagnosed by rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) is associated with higher mortality in patients with severe trauma. Anesth Analg. 2011;113(5):1003–12. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31822e183f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henry D, Carless P, Fergusson D, et al. The safety of aprotinin and lysinederived antifibrinolytic drugs in cardiac surgery: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):183–93. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]