Abstract

A number of studies have shown that the outer membrane protein FomA found in Fusobacterium nucleatum demonstrates great potential as an immune target for combating periodontitis. Lactobacillus acidophilus is a useful antigen delivery vehicle for mucosal immunisation, and previous studies by our group have shown that L. acidophilus acts as a protective factor in periodontal health. In this study, making use of the immunogenicity of FomA and the probiotic properties of L. acidophilus, we constructed a recombinant form of L. acidophilus expressing the FomA protein and detected the FomA-specific IgG in the serum and sIgA in the saliva of mice through oral administration with the recombinant strains. When serum containing FomA-specific antibodies was incubated with the F. nucleatum in vitro, the number of Porphyromonas gingivalis cells that coaggregated with the F. nucleatum cells was significantly reduced. Furthermore, a mouse gum abscess model was successfully generated, and the range of gingival abscesses in the immune mice was relatively limited compared with the control group. The level of IL-1β in the serum and local gum tissues of the immune mice was consistently lower than in the control group. Our findings indicated that oral administration of the recombinant L. acidophilus reduced the risk of periodontal infection with P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum.

KEY WORDS: FomA, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, periodontal infection

INTRODUCTION

It has been reported that targeting Porphyromonas gingivalis, the most important pathogen in periodontal disease, can reduce the likelihood of P. gingivalis infection and slow the progression of periodontal disease [1–5]. However, because periodontitis is a multi-bacterial infectious disease, an antigen that allows targeting of P. gingivalis alone is not ideal for use in vaccine development. Instead, it is important to screen for an antigen that will generate a periodontal vaccine against the majority of periodontal pathogens.

A dental plaque biofilm, consisting of a well-organised microbial community found on the dental surface, is an essential component of periodontal disease. Bacterial coaggregation is necessary during the early stage of biofilm formation [6]. Therefore, blocking coaggregation is a suitable strategy for the prevention of periodontal disease [7]. Fusobacterium nucleatum, a common periodontal pathogen, colonises the plaque biofilm in the early stage of biofilm formation [8, 9]. Because F. nucleatum adheres to almost all oral bacteria, it is considered to be the most important bio-bridge involved in the formation of plaque biofilm [3, 6, 10, 11]. FomA, the major outer membrane porin protein in F. nucleatum [12–14] attaches F. nucleatum to the surface of the tooth and oral mucosa by binding to the salivary statherin-derived peptide [15]. Studies have shown that the FomA receptor protein plays an important role in the conglutination of F. nucleatum and other oral bacteria [16–18]. Therefore, FomA is a candidate target for prevention of periodontal disease [19].

Immunising the mucosal membrane with a viable bacterial carrier provides an antigen delivery pathway similar to natural infection and induces the production of protective antibodies (e.g., sIgA, IgM, IgG), both locally and at other mucosal locations through a common membrane mechanism. There is a long history of use of Lactobacillus in the food industry [20]. Lactobacillus is a genus of probiotic bacteria that occur on the surface of oral and intestinal mucosal membranes and produce an obvious protective effect in periodontal tissue by competing for adhesion sites, nutrients and growth factors, enhancing host immune responses, and producing antimicrobial compounds, including acids [21]. In a previous study, we demonstrated that Lactobacillus acidophilus is a protective factor for periodontal tissues [22, 23]. Moreover, lactic acid bacteria do not display immunogenicity, but when they are used as delivery vehicles for mucosal immunisation, these bacteria can assist the antigen in improving the specific immune response of the mucosa by inducing the production of protective antibodies [24]. Therefore, Lactobacillus represents an ideal antigen delivery vehicle for mucosal immunisation. The Lactobacillus vector system has been used to express exogenous proteins and to induce a mucosal immune response [25–27].

The FomA protein is a potential immune target for fighting periodontal diseases that exhibits significant advantages, and L. acidophilus bacteria are excellent delivery vehicles for mucosal immunisation. Therefore, in this study, we expressed the fomA gene in L. acidophilus to exploit the dual benefits of its health-promoting and antigen-delivery effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Culture

L. acidophilus (ATCC 4356) was cultured in Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) broth (BD, USA) under anaerobic conditions for 24 h at 37 °C The F. nucleatum (ATCC 10953) and P. gingivalis (ATCC 33277) strains were cultured in BHI broth (BD, USA) in an anaerobic workstation (Don Whitley Science, England) at 37 °C for 2 days without shaking. Escherichia coli DH5α was grown in Luria–Bertani (LB) broth (BD, USA) supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C with shaking. These bacterial strains were maintained at the Shanghai Oral Medicine Key Laboratory, Shanghai, China.

Construction of Recombinant L. acidophilus Expressing the FomA Protein

A standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay was employed to generate the F. nucleatum fomA gene using the following conditions: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles at 95 °C for 45 s, 57 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min. The forward PCR primer was (5′-AAATT TCTAGA GAAACAACCATGAAAAAATTAGCATTAGTATTA-3′), which included the XbaI restriction site (TCTAGA), and the reverse PCR primer was (5′-GTC AAGCTT ATTAATAATTTTTATCAATTTTAACCTTAGCTAAGC-3′), which contained the HindIII restriction site (AAGCTT). The purified fomA gene was cloned into the pUC57 plasmid, and E. coli DH5α competent cells were used as temporal expression vehicles for the amplification and identification of the fomA gene. To secrete the heterologous FomA protein from the cells [28], the fomA gene was recovered via double digestion using XbaI and HindIII and then ligated to the Usp45 signal peptide (ATGAAAAAAAAGATTATCTCAGCTATTTTAATGTCTACAGTGATACTTTCTGCTGCAGCCCCGTTGTCAGGTGTTACGCT; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., China). The Usp45–fomA gene fragment was inserted into the pUC57 plasmid, which was subsequently transformed into DH5α competent cells for identification and sequencing. Next, double digestion was conducted to recover the fomA–Usp45 gene fragment, which was integrated into the pMG36e plasmid. DH5α competent cells were transformed with the pMG36e–fomA–Usp45 plasmid, and the transformants were selected on LB plates containing 200 μg/ml erythromycin. The plasmids were extracted from positive colonies and identified via double digestion with XbaI and HindIII, followed by gene sequence analysis. Finally, the pMG36e–fomA–Usp45 plasmid was introduced into L. acidophilus through electroporation, in accordance with previously described methods [29].

Expression of Recombinant FomA

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 10 %), staining with Coomassie blue, and Western blotting were used to detect protein expression. The recombinant L. acidophilus strain was inoculated into MRS medium containing 200 μg/ml erythromycin and cultured overnight. The bacterial cells were treated with bacteriolysin and a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell supernatants were then mixed with SDS loading buffer and boiled for 5 min. SDS-PAGE, and staining with Coomassie blue were performed to detect protein expression. A separate aliquot of the supernatants was used for Western blot analysis. The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by electroblotting, and nonspecific binding to the membrane was blocked via incubation for 1 h in 5 % (w/v) non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween-20 (TBST) at RT, followed by incubation with a rabbit anti-fomA polyclonal antibody (Novoprotein Scientific Inc., China) overnight at 4 °C. After washing four times with TBST, the membrane was incubated for 1 h with anti-rabbit/mouse fluorescence-labelled secondary antibodies (Sigma). After washing four times with TBST, the Odyssey fluorescence imaging system was used to visualise the bound antibodies.

Immunisation of Mice with the Recombinant Strains

Female C57BL/6 mice (aged 6 weeks) were purchased from Shanghai Super B&K Laboratory Animal Corp., Ltd. The mice were maintained in the animal laboratory of the Shanghai Oral Medicine Key Laboratory, and the experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine Animal Ethics Committee.

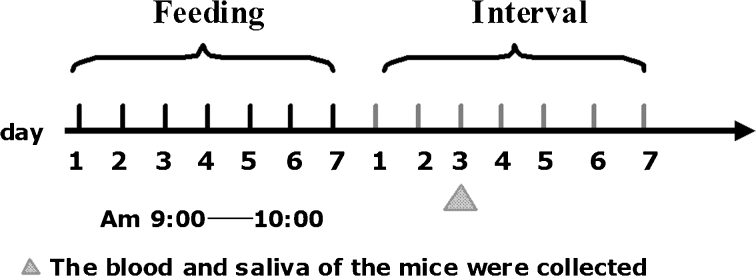

La-fomA and La-pMG36e bacterial suspensions were prepared as described in Section 2.2. C57BL/6 mice (30 in total, aged 9 weeks, weighing 20–25 g) were randomly divided into three groups and immunised orally with La-fomA (experimental group), La-pMG36e (control group), or sterile PBS buffer (blank group). Oral doses (100 μl) were administered daily via gavage between 9 and 10 a.m. for 7 days, followed by a 7-day interval. A second cycle of feeding for 7 days followed by 7 days of withdrawal was performed (Fig. 1). Blood samples were collected from the mice via the vena orbitalis posterior plexus once a week, and their saliva was collected using sterile cotton swabs. The samples were stored at −80 °C.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the process of feeding with the recombinant L. acidophilus cells. Oral doses (100 μl) were administered daily via gavage between 9 and 10 a.m. for 7 days, followed by a 7-day interval. Next, a second 7-day cycle of feeding followed by 7 days of withdrawal was performed. Blood and saliva samples were collected once a week.

Detection of a FomA-Specific Antibody in the Mouse Serum and Saliva

The antibody levels in the serum and saliva were determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). Briefly, each well was coated with 2 μg of FomA protein and blocked with PBS containing 1 % bovine serum albumin. After blocking, serial dilutions (exponential dilution) of the serum samples were added in duplicate. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, washed, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG or IgA (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., USA) at 4 °C for 20 h. Finally, the colour was developed by the addition of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) and H2O2, and the absorbance was read after 10 min at 450 and 570 nm in an ELISA reader. The difference between the OD values obtained at the tow different wavelengths was used as the final index.

Neutralisation of Bacterial Adhesion and Co-aggregation by FomA

The F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 strain was cultured in BHI broth under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 2 days. After centrifugation at 4,000 × g at 4 °C for 5 min, the bacterial pellet was resuspended, and the concentration was adjusted to an optical density (OD) of 1.5 at 550 nm using fresh BHI broth containing 4 % (volume ratio) mouse serum. To allow the antibodies against fomA to mix with the bacteria, the F. nucleatum cells were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h under anaerobic conditions. The same method was used for the P. gingivalis cells.

After incubation for 1 h, the cells were mixed gently using a micropipette, and the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis cells were either transferred individually or equal volumes of the bacterial strains were mixed and transferred to 24-well nonpyrogenic polystyrene plates. The plates were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. Each well was washed gently with PBS (pH 7.2) three times to remove the planktonic bacteria, and fresh BHI broth was added. Following repeated beating of the plate with a pipette, the bacteria adhering to the 24-well plate were washed off the surface. After a 10-fold gradient dilution, the bacteria were distributed evenly into culture plates containing BHI, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 72 h under anaerobic conditions. Finally, the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis colonies were counted and recorded.

Neutralisation of Biofilm Formation by FomA

F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis were prepared as described above. Before being transferred to a 96-well plate, the bacteria were diluted 100-fold. In accordance with the obtained growth curves, a biofilm was formed following incubation of the pathogenic bacteria for 48 h at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. After incubation for 24 h, the broth was replaced with fresh BHI supplemented with 4 % (volume ratio) mouse serum. Each well was washed gently with PBS (pH 7.2) three times to remove planktonic bacteria, after which 50 μl of 3-(4,5)-dimethylthiahiazo (−z-y1)-3,5-di-phenytetrazoliumromide (MTT) was added, and the plates were incubated again for 4 h under anaerobic conditions in the dark. The MTT was removed, and 100 μl of dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) was added to each well. After gentle mixing for 10 min using an oscillator, the optical density in each well (490 nm) was determined using an ELISA reader. Each sample was prepared in triplicate, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Neutralisation of FomA Against Bacterial Adhesion to KB Cells

The KB cell line was provided by the Life Science Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Shanghai Cell Resource Center and subcultured in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium containing 10 % calf serum. Monolayers of the KB cells were prepared on glass coverslips placed in six-well tissue culture plates.

The F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis were prepared as described in Section 2.2, and KB cells were seeded at a concentration of 5×105 cells/cm2. Then, 0.2 ml of the bacterial suspensions was mixed with 1.8 ml of 1640 cell culture medium containing 2 % calf serum, and 4 % mouse serum and was added to six-well plates. After co-culturing for 1, 2, or 4 h, the plates were washed twice with sterile saline, fixed with methanol for 15 min, stained with Gram stain, and examined microscopically. For each monolayer on a glass coverslip, the number of adherent bacteria was evaluated in 50 random microscopic fields. Each assay included three replicate wells and was repeated three times, and the counts were then averaged.

Construction of a Mouse Gum Abscess Model

A mouse gum abscess model was constructed to test the immune effects of recombinant L. acidophilus [19]. Briefly, 100 μl of live F. nucleatum (3 × 108 CFU/ml in PBS), P. gingivalis (3 × 103 CFU/ml in PBS) or F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis (3 × 108 CFU/ml plus 3 × 103 CFU/ml in PBS, respectively) was suspended in 100 μl of PBS and inoculated into the oral cavities of immunised mice every day for 3 days. A 30-μl aliquot of the sample was injected into the gums of the lower incisors using a 28-gauge needle, while 30 μl was dropped directly into the oral cavity, and the remaining 40 μl was spread over the surface of the tongue.

The mice immunised with recombinant L. acidophilus expressing the FomA protein (La-fomA) were the experimental group; those immunised with L. acidophilus containing the empty vector plasmid (La-pMG36e) were the control group; and mice treated with sterile PBS buffer served as the blank group. The mice in each group were further subdivided into two groups, which were inoculated with either F. nucleatum or F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis.

Evaluation of Inflammation in Gum

After 3 days, the gum inflammation status was assessed in anaesthetised mice, and the maximum diameter of the gingival abscesses was measured using a Vernier calliper (Traceable Digital Caliper; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Each abscess was scored according to the following standard: 1, ≤1 mm; 2, ≤2 mm; 3, ≤3 mm; and 4, >3 mm.

Blood was collected from the mouse hearts using a needle, and the serum was isolated and stored at −80 °C. The mandibular and tongue mucosal tissues of the mice were collected and added to PBS buffer at a concentration of 100 mg/ml. After homogenisation, the supernatant was collected via centrifugation at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 20 min and then stored at −80 °C. The levels of IL-1β in the serum and the oral mucosal tissues were determined using ELISA kits (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Statistical Analyses

The data are presented as the mean ± SD. A paired-sample t-test was employed to compare the mean values of the replicate samples. The p value criterion used to determine statistical significance was *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01

RESULTS

Construction of Recombinant L. acidophilus Expressing FomA Protein

Construction of the Recombinant Plasmid pMG36e–fomA–Usp45

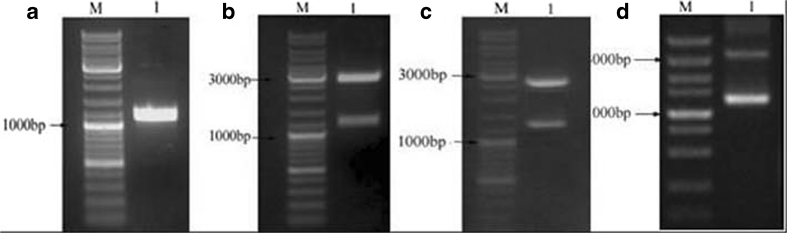

Analysis via agarose gel electrophoresis allowed the PCR product amplified with the fomA-specific primers to be identified as a 1,046-bp sequence, which is consistent with the molecular weight of the fomA gene (Fig. 2a). Using BLAST software, the sequence was compared with sequences published in GenBank and was found to be consistent with the Fn10953 fomA gene (GenBank Accession Number: X72583). The recombinant plasmids pUC57–fomA, pUC57–fomA–Usp45, and pMG36e–fomA–Usp45 were constructed and verified via double-enzyme cleavage and gene sequence analysis, and Fig. 2b,c, and d shows that electrophoretic bands of the expected molecular weights were obtained. The sequencing results were consistent with the presence of the Fn10953 fomA gene.

Fig. 2.

Construction of the recombinant strains and electrophoretic analyses. M represents the DL 10,000 marker (TAKARA, Japan). a Electrophoresis of the PCR products generated using specific fomA primers. 1 The fomA gene (1,046 bp). b Electrophoresis of the PUC57–fomA plasmid digested with XbaI and HindIII. 1 Restriction enzyme fragments, 2,700 and 1,046 bp. c Electrophoresis of the pUC57–fomA–Usp45 plasmid digested with XbaI and HindIII. 1 Restriction enzyme fragments, 2,700 and 1,259 bp. d Electrophoresis of the pMG36e–fomA–Usp45 plasmid digested with XbaI and HindIII. 1 Restriction enzyme fragments, 1,200 and 3,600 bp.

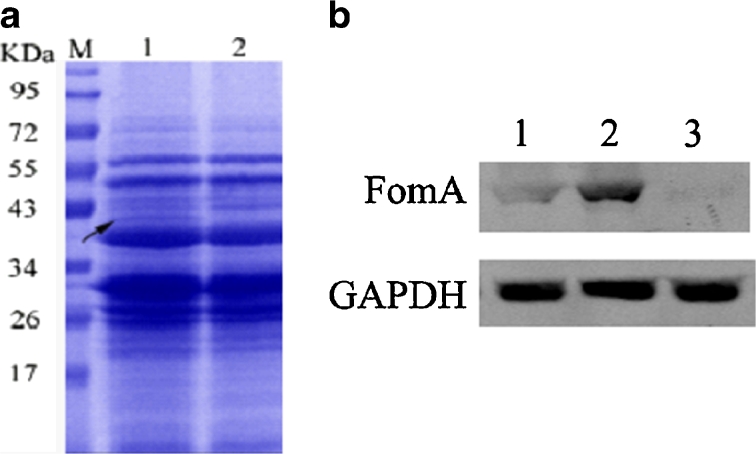

Expression and Identification of FomA Protein

The expression of the FomA protein in recombinant L. acidophilus was analysed through SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Figure 3a shows that protein bands with a molecular weight of approximately 41 kDa were obtained. In the Western blots, these bands (Fig. 3b) demonstrated reactivity with the FomA-specific antibody, indicating that the FomA protein was expressed in recombinant L. acidophilus. Furthermore, the Western blots showed that the FomA protein was expressed at higher levels in recombinant L. acidophilus when it was fused to the Usp45 signal peptide than when Usp45 was absent, indicating that the Usp45 signal peptide resulted in effective secretion of the FomA protein into the bacterial supernatant.

Fig. 3.

Expression and identification of the fomA protein. a SDS-PAGE analysis showing 41-kDa FomA (arrows) expressed in L. acidophilus (lane 1), the control strain (lane 2), and protein standards (lane M). b Western blot analysis showing that FomA protein was expressed at higher levels in L. acidophilus expressing fomA fused to the Usp45 signal peptide (lane 2) compared with L. acidophilus expressing fomA without Usp45 (lane 1) or the empty vector (lane 3).

FomA-Specific IgG in Mouse Sera and sIgA in Mouse Saliva

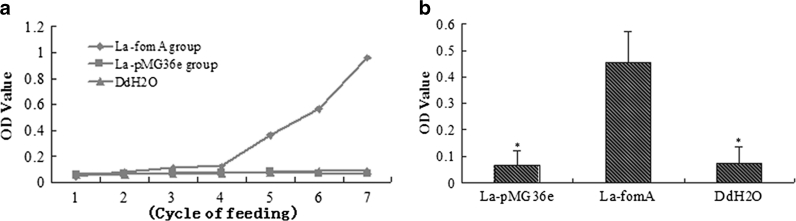

After the fifth feeding cycle, FomA-specific IgG was detected in the serum of the mice in the La-fomA group, and after the seventh cycle, FomA-specific IgA was detected in the saliva of these mice. As shown in Fig. 4, the levels of IgG increased gradually over the feeding cycles.

Fig. 4.

Anti-FomA antibody levels following oral vaccination with L. acidophilus expressing the FomA protein. The difference between the OD 450 and OD 570 nm was taken as the final index. a Levels of FomA-specific IgG in the serum of the immunised mice. b Levels of FomA-specific sIgA in the saliva of the immunised mice. *Compared with the control group, a p value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Influence of FomA-Specific Antibodies on Bacterial Adhesion and Coaggregation.

When the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis were cultured alone, the mean numbers of F. nucleatum colonies obtained in the presence of mouse sera either containing antibodies to FomA or not were 6.3 × 104 and 6.6 × 104, respectively, and the mean numbers P. gingivalis colonies were 5.6 × 102 and 5.0 × 102, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant. When F. nucleatum and P. gingival cells were co-cultured, the mean number of F. nucleatum colonies produced in the presence of both types of mouse serum was approximately 5 × 104. However, the mean numbers of P. gingivalis colonies produced in the negative and positive FomA-specific IgG serum groups were 4.6 × 105 and 2.6 × 102, respectively, and this difference was statistically significance (p<0.01).

Influence of FomA-Specific Antibodies on the Formation of Microbial Biofilm

After incubation for 48 h at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions (Table 1), the mean optical density at 490 nm of the F. nucleatum incubated with serum positive or negative for FomA antibodies was 1.42 or 1.51, respectively, and that of P. gingivalis was 0.76 or 0.64, respectively. The differences in the OD readings obtained for the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis cells in the presence of the mouse sera were not statistically significant. In addition, the OD 490 nm values for the co-cultured F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis cells incubated with the mouse serum containing antibodies to FomA were lower than for the cells incubated with mouse serum negative for the FomA antibody; the obtained OD 490 nm values were 1.43 and 1.98, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Optical Density Value of Different Bacterial Biofim in 96-Well Plate at 490 nm (mean ± SD)

| Bacteria | Mice serum | |

|---|---|---|

| fomA antibodies (+) | fomA antibodies (−) | |

| Fn | 1.42 ± 0.52 | 1.51 ± 0.41 |

| Pg | 0.76 ± 0.33 | 0.64 ± 0.52 |

| Fn + Pg | 1.43 ± 0.33 | 1.98 ± 0.56* |

*Compared with the group treated by the mice serum containing fomA antibodies, p<0.05

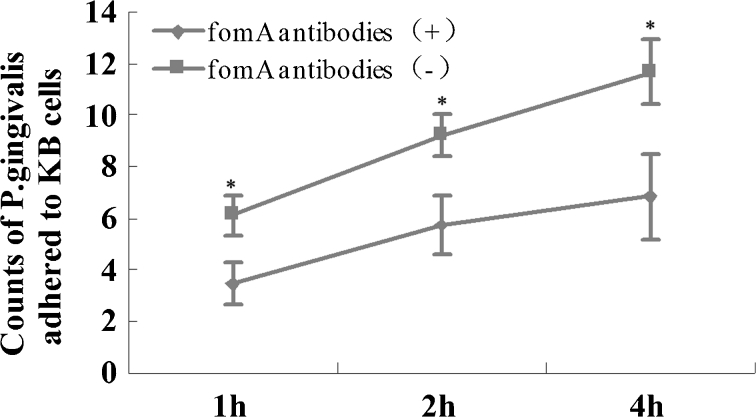

Influence of FomA-Specific Antibodies on Bacterial Adhesion to KB Cells

To assess the adhesion of the bacteria to KB cells, F. nucleatum or P. gingivalis cells were cultured with KB cells. The differences in the numbers of F. nucleatum or P. gingivalis cells adhered to KB cells in the presence of the two types of mouse sera at the three time points (1, 2, and 4 h) were not statistically significant. When F. nucleatum and P. gingival cells were co-cultured with KB cells, the number of P. gingivalis that adhered to the KB cells (mediated by F. nucleatum) in the presence of mouse serum positive for FomA-specific IgG was lower than that in the presence of serum negative for the antibodies at all three time points (1, 2, and 4 h) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Results of adhesion assays. After P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum were co-cultured with KB cells for 1, 2, or 4 h, the number of P. gingivalis cells adhered to the KB cells, mediated by F. nucleatum, was assessed. The level of P. gingivalis in the experimental group was lower than in the control group at all three time points (p < 0.05).

Influence of FomA-Specific Antibodies on Gum Inflammation Mediated by F. nucleatum

Condition of Mouse Gingival Abscesses

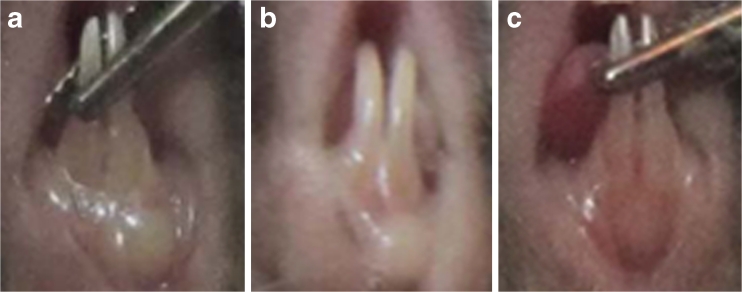

After 3 days of injection, as shown in Fig. 6, the gums surrounding the lower incisors of the mice were red and swollen, and abscesses had formed. The gingival abscess scores in the mice immunised with the recombinant strain (La-fomA) were lower than in the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). The data obtained in these examinations are shown in Table 2.

Fig. 6.

Morphologies of swollen gums in mice treated with P. gingivalis plus F. nucleatum. After 3 days of injection, the gums surrounding the lower incisors were red and swollen, and abscesses had formed. The gingival abscesses in the mice in the experimental group were less severe than in the control and blank groups. a The mice immunised with PBS served as the blank group. b The mice immunised with the recombinant strain La-pMG36e served as the control. c The mice immunised with the recombinant strain La-fomA.

Table 2.

Scores of Mice Gingival Abscess Among Three Groups (mean ± SD)

| Groups | Injection bacteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Fn | Fn + Pg | |

| Experiment group (La-fomA) | 2.6 ± 0.55ac | 2.0 ± 0.45abc |

| Control group (La-PMG36e) | 3.0 ± 0.42 | 3.9 ± 0.45b |

| Blank group (PBS) | 3.2 ± 0.92 | 4.3 ± 0.81b |

aCompared with control group, p<0.05

bIn the same group, compared with the single Fn injection, p<0.05

cCompared with Blank group, p<0.05

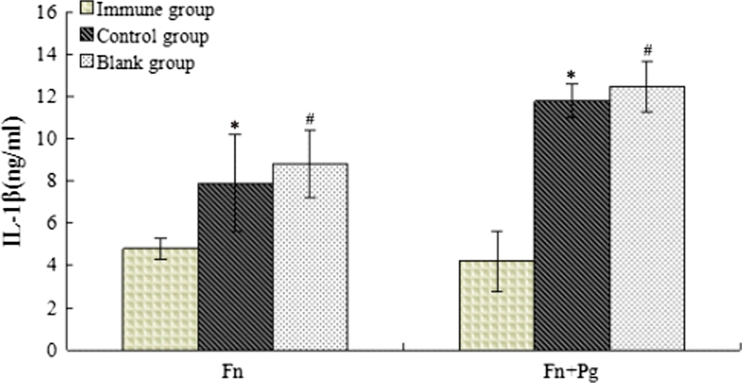

IL-1β Concentration in the Mouse Sera

Figure 7 shows that the mean IL-1β concentration in the mice injected with F. nucleatum alone or with F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis was lower than in the control group, and this difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Levels of IL-1β in mouse serum samples. After 3 days of injection, blood was collected from the heart, and the serum was isolated. The levels of IL-1β in the mouse serum were determined using ELISA kits in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, USA). Following injection with both F. nucleatum alone and F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis, the mean IL-1β levels in the experimental group of mice were lower than in the control group (*,# p < 0.05).

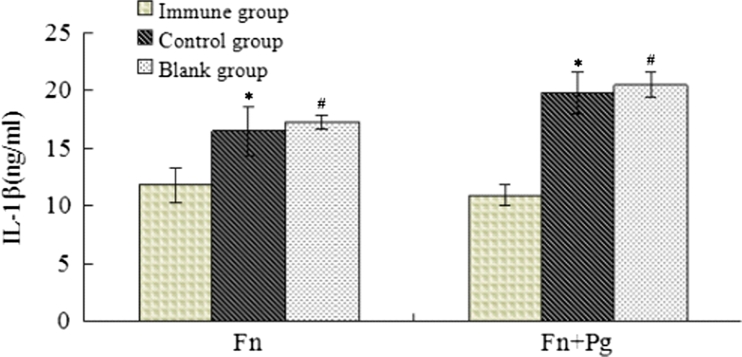

IL-1β Concentration in the Oral Mucosal Tissues of the Mice

Compared with the results obtained for the mouse sera, the mean IL-1β concentration was increased in the oral mucosal tissues of the mice in both the experimental and control groups. Consistent with the results from the mouse serum samples, the mean IL-1β concentration in the experimental group of mice was lower than in the control group, both for the mice injected with F. nucleatum alone and with F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Levels of IL-1β in oral mucosal tissues of mice. After 3 days of injection, the mandibular and tongue mucosal tissues of the mice were collected, and 100 mg/ml PBS buffer was added. After homogenisation, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 20,000×g at 4 °C for 20 min. The IL-1β levels in the serum and oral mucosal tissues were determined using ELISA kits (Thermo Scientific, USA). The IL-1β levels in the experimental group of mice were lower than in the control group following injections with both F. nucleatum alone and with F. nucleatum plus P. gingivalis (*,# p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

F. nucleatum is not only one of the most important pathogens involved in periodontal disease but also acts as a "bridge bacterium" in the formation of dental plaques. The FomA protein, which is the main outer membrane porin protein in F. nucleatum, plays an important role in regulating the permeability of the microbial biofilm. Hidetaka (2010) immunised mice intranasally with the FomA protein isolated from F. nucleatum and detected FomA-specific IgG antibodies in the serum and sIgA on the surface of the oral mucosa [15], which confirmed the immunogenicity of the FomA protein in mucosal immunity. However, it is difficult to purify the FomA protein from F. nucleatum, which is a major obstacle to the experimental and clinical application of FomA. Therefore, developing a convenient and effective method to express and deliver the FomA protein is important.

In this study, we constructed a recombinant L. acidophilus strain expressing the FomA protein from F. nucleatum and detected FomA-specific IgG in the serum and sIgA in the saliva of mice following oral administration with the recombinant strains. This study is the first to confirm the immunogenicity of the recombinant FomA protein expressed by L. acidophilus strains in the mucosal immune system, demonstrating that it is possible to use recombinant strains for periodontal immunisation. Liu et al. [19] immunised mice intranasally using an E. coli expression system and detected FomA-specific-antibodies in the serum. However, because E. coli contains endotoxin, it cannot be used directly in the clinic. As Lactobacillus does not contain endotoxin, the exogenous protein generated by these bacteria can be isolated directly without purification. In addition, Lactobacillus species exhibit only one cell membrane layer, which allows foreign proteins to be secreted outside of the cell directly under the control of a signal peptide; hence, it is easy to obtain the desired proteins [30–32]. Therefore, Lactobacillus exhibits advantages over E. coli regarding the expression and delivery of the FomA protein.

A common membrane mechanism is an important advantage in mucosal immunity. Exogenous proteins secreted by lactic acid bacteria, which adhere to and colonise the mucosa of the respiratory and digestive tracts, can induce the production of specific antibodies not only in local mucosa but also on other mucosal surfaces through a common membrane mechanism. In the present study, we detected FomA-specific IgA antibodies in the mouse saliva samples, which could be the result of the common membrane mechanism. The FomA-specific IgA antibodies at the oral mucosal surface may exert an antagonistic effect on the periodontal pathogens.

Usp45 is a protein signal peptide derived from Lactococcus lactis. Because this signal peptide effectively controls the secretion of foreign proteins, it is often used to express such proteins in lactic acid bacteria. It is noteworthy that when we fused the synthetic signal peptide Usp45 downstream of the P32 promoter in the PMG36e plasmid, after electroporation, the FomA protein was detected in the supernatant of the recombinant strains. However, in the absence of the Usp45 signal peptide, the target protein remained inside the bacteria in a precipitated form in inclusion bodies. Therefore, the Usp45 signal peptide guided the target protein through the membrane and wall of the L. acidophilus cells and secreted it into the supernatant.

It has been reported that FomA is involved in F. nucleatum adhesion and coaggregation with other bacteria [16–18]. However, whether the FomA-specific antibodies induced by the recombinant strains inhibit F. nucleatum adhesion and coaggregation with other bacteria is unknown. In our adhesion experiment, we determined that compared with the control group, the number of P. gingivalis colonies decreased significantly in the experimental group. It is possible that the FomA antibody blocked the copolymerisation of P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum, thus indirectly blocking the adhesion of P. gingivalis to the 24-well plates. Using methods described in previous studies, we performed the MTT assay to evaluate the number of living bacteria after 48 h of culture and analysed the influence of FomA on the formation of biofilms. Similar to the results of the adhesion experiment, the FomA antibodies obstructed the formation of the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis biofilms. These data indicated that the FomA-specific antibodies induced by the recombinant strains inhibited the coaggregation of F. nucleatum with P. gingivalis in vitro.

In addition, we mixed the F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis strains to generate a mouse gingival abscess model. To evaluate the severity of the resultant gingival abscesses and the possibility of using the recombinant strains as a periodontal vaccine, we measured the size of the abscesses and determined the levels of the inflammatory factor IL-1β in mouse serum samples and local gum tissues. IL-1β is an important cellular inflammatory factor that is correlated with the severity of periodontal disease [33]. The results clearly demonstrated that there the gingival abscesses in the mice in the experimental group were less severe than in the control group. The levels of IL-1β in the mouse serum samples and local gum tissues were also lower than in the control group. These results were consistent with the in vitro results, demonstrating that blocking FomA inhibited the pathogenicity of P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum. Overall, our findings indicated that oral administration of the recombinant L. acidophilus reduced the risk of periodontal infection with P. gingivalis and F. nucleatum.

In summary, we determined that the FomA protein plays an important role in the coaggregation of F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis. Recombinant L. acidophilus expressing the FomA protein from F. nucleatum induced specific antibodies in the serum and saliva of mice following immunisation through the gastrointestinal mucosa. This pattern of immunisation reduced the degree of periodontal abscesses caused by F. nucleatum and P. gingivalis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science Foundation of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (No. 11411950900), and there are no ethical/legal conflicts involved in the article.

References

- 1.Hiratsuka K, Abiko Y, Hayakawa M, Ito T, Sasahara H, Takiguchi H. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis 40-kDa outer membrane protein in the aggregation of P. gingivalis vesicles and Actinomyces viscosus. Archives of Oral Biology. 1992;37:717–724. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(92)90078-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcotte H, Koll-Klais P, Hultberg A, Zhao Y, Gmur R, Mandar R, Mikelsaar M, Hammarstrom L. Expression of single-chain antibody against RgpA protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Lactobacillus. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2006;100:256–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaniztki B, Hurwitz D, Smorodinsky N, Ganeshkumar N, Weiss EI. Identification of a Fusobacterium nucleatum PK1594 galactose-binding adhesin which mediates coaggregation with periopathogenic bacteria and hemagglutination. Infection and Immunity. 1997;65:5231–5237. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5231-5237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamajima S, Maruyama M, Hijiya T, Hatta H, Abiko Y. Egg yolk-derived immunoglobulin (IgY) against Porphyromonas gingivalis 40-kDa outer membrane protein inhibits coaggregation activity. Archives of Oral Biology. 2007;52:697–704. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakao R, Hasegawa H, Ochiai K, Takashiba S, Ainai A, Ohnishi M, Watanabe H, Senpuku H. Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis elicit a mucosal immune response. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Watson GK, Allison C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and coaggregation in anaerobe survival in planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities during aeration. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66:4729–4732. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4729-4732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a microbial biofilm. Caries Research. 2004;38:204–211. doi: 10.1159/000077756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu PF, Zhu WH, Huang CM. Vaccines and photodynamic therapies for oral microbial-related diseases. Current Drug Metabolism. 2009;10:90–94. doi: 10.2174/138920009787048365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 1996;9:55–71. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rickard AH, Gilbert P, High NJ, Kolenbrander PE, Handley PS. Bacterial coaggregation: An integral process in the development of multi-species biofilms. Trends in Microbiology. 2003;11:94–100. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(02)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang MS, Kim BG, Chung J, Lee HC, Oh JS. Inhibitory effect of Weissella cibaria isolates on the production of volatile sulphur compounds. Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2006;33:226–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleivdal H, Benz R, Jensen HB. The Fusobacterium nucleatum major outer-membrane protein (FomA) forms trimeric, water-filled channels in lipid bilayer membranes. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;233:310–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.310_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleivdal H, Benz R, Tommassen J, Jensen HB. Identification of positively charged residues of FomA porin of Fusobacterium nucleatum which are important for pore function. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1999;260:818–824. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kremer BH, van Steenbergen TJ. Peptostreptococcus micros coaggregates with Fusobacterium nucleatum and non-encapsulated Porphyromonas gingivalis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2000;182:57–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagaki H, Sekine S, Terao Y, Toe M, Tanaka M, Ito HO, Kawabata S, Shizukuishi S, Fujihashi K, Kataoka K. Fusobacterium nucleatum envelope protein FomA is immunogenic and binds to the salivary statherin-derived peptide. Infection and Immunity. 2010;78:1185–1192. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01224-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman J, DiRienzo JM. Evidence for the existence of two classes of corncob (coaggregation) receptor in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Oral Microbiology and Immunology. 1988;3:145–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.1988.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufman J, DiRienzo JM. Isolation of a corncob (coaggregation) receptor polypeptide from Fusobacterium nucleatum. Infection and Immunity. 1989;57:331–337. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.2.331-337.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kinder SA, Holt SC. Localization of the Fusobacterium nucleatum T18 adhesin activity mediating coaggregation with Porphyromonas gingivalis T22. Journal of Bacteriology. 1993;175:840–850. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.840-850.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu PF, Shi W, Zhu W, Smith JW, Hsieh SL, Gallo RL, Huang CM. Vaccination targeting surface FomA of Fusobacterium nucleatum against bacterial co-aggregation: Implication for treatment of periodontal infection and halitosis. Vaccine. 2010;28:3496–3505. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dicks LM, Botes M. Probiotic lactic acid bacteria in the gastro-intestinal tract: Health benefits, safety and mode of action. Beneficial Microbes. 2010;1:11–29. doi: 10.3920/BM2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haukioja A. Probiotics and oral health. European Journal of Dentistry. 2010;4:348–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao JJ, Le KY, Feng XP, Ma L. Antagonistic effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium adolescents on periodontalpathogens in vitro. Shanghai Kou Qiang Yi Xue. 2011;20:364–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao JJ, Feng XP, Zhang XL, Le KY. Effect of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Lactobacillus acidophilus on secretion of IL1B, IL6, and IL8 by gingival epithelial cells. Inflammation. 2012;35:1330–1337. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thoreux K, Schmucker DL. Kefir milk enhances intestinal immunity in young but not old rats. Journal of Nutrition. 2001;131:807–812. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.3.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grangette C, Muller-Alouf H, Goudercourt D, Geoffroy MC, Turneer M, Mercenier A. Mucosal immune responses and protection against tetanus toxin after intranasal immunization with recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69:1547–1553. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1547-1553.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorvig E, Gronqvist S, Naterstad K, Mathiesen G, Eijsink VG, Axelsson L. Construction of vectors for inducible gene expression in Lactobacillus sakei and L plantarum. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;229:119–126. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song AA, Abdullah JO, Abdullah MP, Shafee N, Rahim RA. Functional expression of an orchid fragrance gene in Lactococcus lactis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13:1582–1597. doi: 10.3390/ijms13021582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Loir Y, Azevedo V, Oliveira SC, Freitas DA, Miyoshi A, Bermudez-Humaran LG, Nouaille S, Ribeiro LA, Leclercq S, Gabriel JE, Guimaraes VD, Oliveira MN, Charlier C, Gautier M, Langella P. Protein secretion in Lactococcus lactis: An efficient way to increase the overall heterologous protein production. Microbial Cell Factories. 2005;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber SD, Solioz M. Efficient transformation of Lactococcus lactis IL1403 and generation of knock-out mutants by homologous recombination. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 2007;47:281–286. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200610297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okafor N, Okeke BC, Umeh C, Ibenegbu C. Secretion of lysine in a broth medium by lactic bacteria and yeasts associated with garri production using a synthetic gene. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1999;28:419–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmgren J, Adamsson J, Anjuere F, Clemens J, Czerkinsky C, Eriksson K, Flach CF, George-Chandy A, Harandi AM, Lebens M, Lehner T, Lindblad M, Nygren E, Raghavan S, Sanchez J, Stanford M, Sun JB, Svennerholm AM, Tengvall S. Mucosal adjuvants and anti-infection and anti-immunopathology vaccines based on cholera toxin, cholera toxin B subunit and CpG DNA. Immunology Letters. 2005;97:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novotny R, Scheberl A, Giry-Laterriere M, Messner P, Schaffer C. Gene cloning, functional expression and secretion of the S-layer protein SgsE from Geobacillus stearothermophilus NRS 2004/3a in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2005;242:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pretzl B, El Sayed N, Cosgarea R, Kaltschmitt J, Kim TS, Eickholz P, Nickles K, Baumer A. IL-1-polymorphism and severity of periodontal disease. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 2012;70:1–6. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2011.572562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]