Abstract

Cognitive impairments are common in depression and involve dysfunctional serotonin neurotransmission. The 5-HT1B receptor (5-HT1BR) regulates serotonin transmission, via presynaptic receptors, but can also affect transmitter release at heterosynaptic sites. This study aimed at investigating the roles of the 5-HT1BR, and its adapter protein p11, in emotional memory and object recognition memory processes by the use of p11 knockout (p11KO) mice, a genetic model for aspects of depression-related states. 5-HT1BR agonist treatment induced an impairing effect on emotional memory in wild type (WT) mice. In comparison, p11KO mice displayed reduced long-term emotional memory performance. Unexpectedly, 5-HT1BR agonist stimulation enhanced memory in p11KO mice, and this atypical switch was reversed after hippocampal adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer of p11. Notably, 5-HT1BR stimulation increased glutamatergic neurotransmission in the hippocampus in p11KO mice, but not in WT mice, as measured by both pre- and postsynaptic criteria. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy demonstrated global hippocampal reductions of inhibitory GABA, which may contribute to the memory enhancement and potentiation of pre- and post-synaptic measures of glutamate transmission by a 5-HT1BR agonist in p11KO mice. It is concluded that the level of hippocampal p11 determines the directionality of 5-HT1BR action on emotional memory processing and modulates hippocampal functionality. These results emphasize the importance of using relevant disease models when evaluating the role of serotonin neurotransmission in cognitive deficits related to psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: AAV, biosensor, MRS, novel object recognition, passive avoidance, S100A10

Introduction

Depressed patients suffer from multiple cognitive impairments, including attention, declarative memory, executive functions and emotional processing.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Such impairments may be an important factor in the slow recovery of particularly recurrent depression and be important for the treatment outcome of a number of psychiatric conditions.1, 8, 9 There is evidence that beneficial effects of antidepressant therapies on cognitive function precede, and even predict, elevation of mood.10, 11 Enhancement of serotonin signaling via antidepressants typically leads to task-dependent improvements of emotional processing. On the contrary, acute tryptophan depletion, results in a relapse of depression in recovered patients and impairment of emotional processing.3, 12

In experimental animals, reduction of serotonin neurotransmission by tryptophan depletion13, 14 or 5-HT1AR agonist treatment15 impair memory function. Stimulation of the 5-HT1BR, a terminal autoreceptor, decreasing 5-HT release, causes memory deficits in rats and mice.16, 17 Studies in rats and 5-HT1BR knockout mice also indicate an important role for the 5-HT1BR in modulation of cognitive and emotional processes.18, 19 To our knowledge, there are no studies in humans on the role of 5-HT1BRs in emotional processing, but PET imaging studies of 5-HT1BR have shown reduced binding potential in depressed individuals and suicide victims.20, 21

Cellular functions of the 5-HT1BR are regulated by its adapter protein p11 (S100A10, annexin II light chain), which recruits 5-HT1BR (and 5-HT4R) to the cell surface.22, 23, 24 Reduction of p11 has been found both in post-mortem human tissue from depressed individuals and suicide victims21, 22, 25 and in a rodent model of depression.22 p11KO mice exhibit a depression-like phenotype and have reduced responsiveness to 5-HT1BR agonists and antidepressants.22, 25

This study examined whether p11 is involved in basal and/or 5-HT1BR-mediated regulation of memory processing, by assessment of WT and p11KO mice after pharmacological 5-HT1BR stimulation. Two memory tasks were utilized to address this issue; (1) the passive avoidance test for emotional memory processing, which is an one-trial associative learning paradigm based on contextual fear conditioning combined with the requirement of the animal to express a ecologically conserved adaptive response, (2) the novel object recognition (NOR) memory test, based on the innate exploration of a novel object and discrimination of a familiar object (see also Supplementary Information).15 To determine the anatomical circuitries involved in p11-mediated regulation of memory performance, somatic gene transfer was used to overexpress p11 in hippocampus. To determine molecular mechanisms underlying actions of p11 in hippocampus, biosensors were used to measure glutamate release, immunoblotting to determine glutamate receptor phosphorylation and magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study neurochemical events associated with p11-mediated regulation of 5-HT1BR function.

Materials and methods

Animals and drugs

For all experiments, adult wildtype (WT), p11HETerozygous (HET) and p11 knockout (KO) mice were used.22, 24, 25, 26 The construct to generate the p11KO mice was derived from a targeting vector spanning the ATG-containing exon of the p11 gene.22 It was electroporated into 129SvEv ES cells and positive clones selected for homologous recombination were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Chimeric males were bred with C57BL/6 females to obtain germ-line transmission. Heterozygous offspring were mated to generate p11 KO and p11 WT mice. The absence of the p11 gene in the p11KO mice was confirmed with southern blotting and in situ hybridization.22 p11HET mice were backcrossed with wildtype C57BL/6 for 10 generations. A PCR procedure has been developed to distinguish p11 WT, p11HET, p11KO mice from heterozygote breedings.22 All experimental animals (p11 WT, p11HET and p11KO mice) were bred at the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. The experiments were performed in agreement with the European Council Directive (86/609/EEC) and approved by the local Animal Ethics Committee (Stockholms Norra Djurförsöksetiska Nämnd). All efforts were made to minimize suffering and the number of animals used.

CP94253 (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) was intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected at 10 mg/kg in 10 ml/kg filtered ddH2O 30 min prior to behavioral testing or sacrifice.26 RS67333 (Tocris Bioscience) was injected once daily at 1 mg/kg i.p. in saline for 6 consecutive days and 30 min prior test.24 GR127935 (N-[4-Methoxy-3-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)phenyl]-2′-methyl-4′-(5-methyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)-1,1′-biphenyl-4-carboxamide hydrochloride) (Tocris) was administered at 10 mg/kg in 10% (2-Hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich) ddH2O 45 min pretraining.27

Passive avoidance and novel object recognition

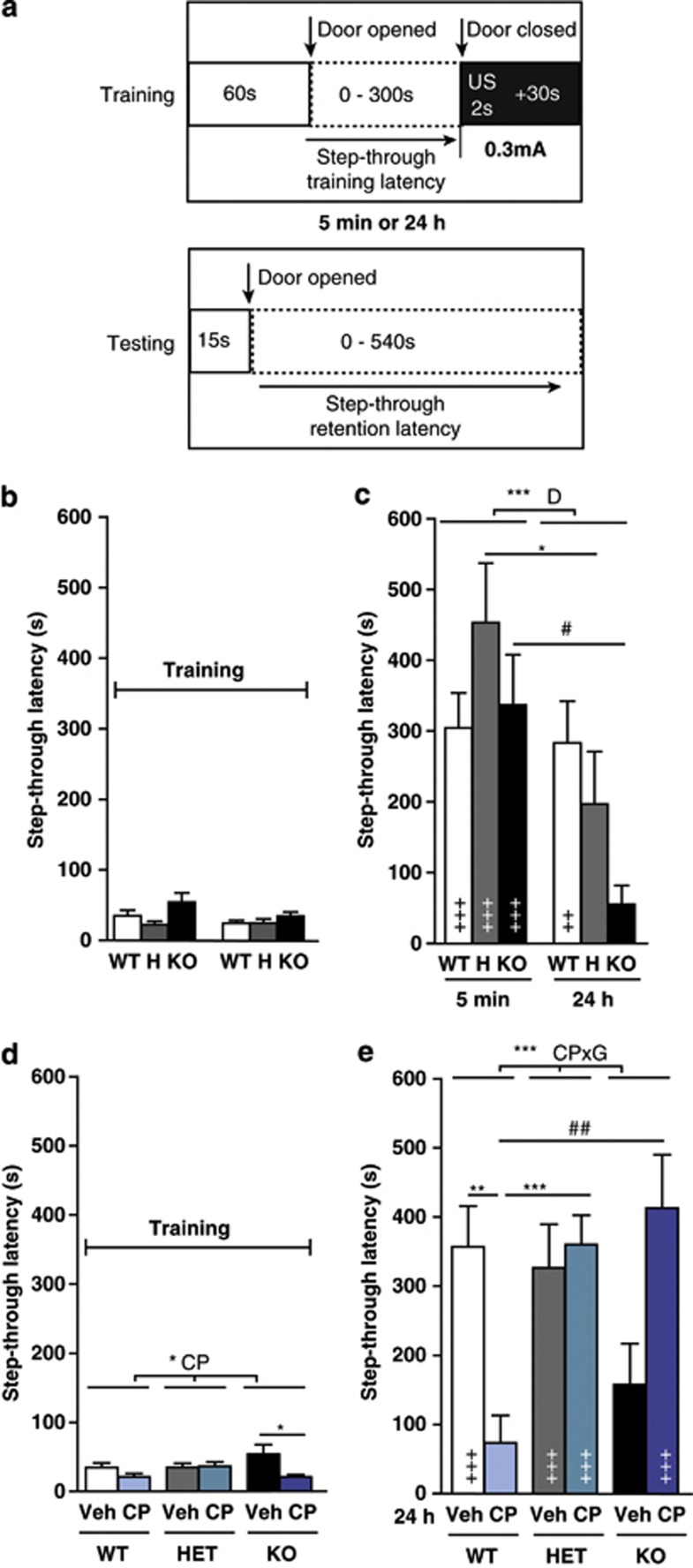

The passive avoidance task for emotional memory was performed as shown in Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure S1a and Supplementary Information.17 Mice explored a bright compartment for 60 s, before step-through to a dark compartment (training latency) and delivery of a weak electrical stimulus (0.3 mA, 2 s scrambled current) through the grid floor. After a 5 min or 24 h delay, the step-through latency to return to the dark compartment was measured (retention latency). The NOR memory task is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S2a and Supplementary Information.

Figure 1.

p11KO mice display memory impairments and atypical pharmacological responses to 5-HT1BR stimulation. Schematic setup of the passive avoidance procedure (a). At training, a mouse explores a bright compartment for 60 s. After door opening, time is measured for the mouse to enter the dark compartment (training latency). Upon step-though, the unconditioned stimulus (US) (0.3 mA, 2 s scrambled current) is delivered. Following a 5 min or 24 h delay, the step-through latency to return to the dark compartment is measured (retention latency). Step-through latencies of mice at training (b) and at the short-term (5 min) or long-term (24 h) (c) memory test. Learning-related avoidance was present in all groups if tested after 5 min, but only in WT after 24 h (c). Reduced training latencies (d) and switched responses to the 5-HT1BR agonist CP94253 (CP) in P11KO on emotional memory function (e). Learning-related avoidance was induced in all groups except for WT CP94253 and P11KO vehicle (e). n=5–13 (b–c), 10–19 (d–e) mice per group. ++P<0.01; +++P<0.001 indicates significant difference between training and testing performances. Data are presented as means±s.e.m. CP: CP94253 (5-HT1BR agonist), P11KO: p11 knock-out mice, H and HET: p11heterozygous mice, WT: wild type mice, G: genotype, Veh: vehicle. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01.

Hippocampal AAV gene transfer of p11

To restore p11 locally in the hippocampus, adeno-associated virus (AAV)–mediated gene transfer of p11 was conducted in the hippocampus of WT and p11KO mice using a vector containing a p11 complementary DNA (cDNA) (AAV.p11).25 As a negative control, WT and p11KO mice received a vector expressing yellow fluorescent protein (AAV.YFP), as described in the Supplementary Information.25, 28

In situ hybridization and radioligand binding

Fresh frozen (14 μm) coronal cryostat sections were prepared and hybridized with 35S-radiolabeled antisense riboprobes against p11 or YFP mRNA25, 29 or for quantitative receptor autoradiography with [125I]cyanopindolol22, 30 Optical densitometric measurements were obtained in defined brain regions using NIH ImageJ 1.40 (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (see Supplementary Information).

Enzyme-based glutamate measures

Glutamate dynamics were assessed on a sub-second timescale by microelectrode array (MEA) recordings with 2 out of 4 electrode sites coated with L-glutamate oxidase enzyme, which breaks down L-Glutamate into α-ketoglutarate and peroxide (H2O2).31, 32, 33 By using constant voltage amperometry with application of a fixed potential, the H2O2 was oxidized, with electron loss, and the resulting current was recorded using a Fast Analytical Sensing Technology (FAST)-16 electrochemistry instrument (Quanteon, L.L.C., Nicholasville, KY, USA). Depolarization-induced glutamate release was induced by an isotonic solution of 120 mM KCl, with or without 10 μM CP94253, ejected for 1 s through a glass micropipette positioned at a distance of 50–100 μm from the MEA recording sites (see Supplementary Information and Supplementary Figures S6a and b).

Western blotting

To preserve protein phosphorylation, naïve wildtype and p11KO mice were sacrificed 30 min after pharmacological treatments using focused microwave irradiation (Muromachi Kikai, Tokyo, Japan), with brain regions dissected and frozen at −80 °C.30 Immunoblotting of total proteins and the phosphorylation state of the studied proteins was performed using primary antibodies for total or phosphospecific sites22 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Information).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Neurochemical profiles were determined in the hippocampus of WT and p11KO mice by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) at the Experimental MR Research Center at Karolinska Institute.34 Magnetic Resonance Images, voxel positioning and MRS were performed on a horizontal 4.7T/40-cm magnet (Bruker BioSpec Avance 47/40; Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) as described in the Supplementary Information.

Statistical analyses

Parametric statistics were utilized after Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) normality test (GraphPad Prism 4.0, San Diego, CA, USA). Data were analyzed with one-way, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or repeated measures two-way ANOVA with subject matching, as described in results. Significant effects on the ANOVAs were further investigated with Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with subject matching were analyzed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis for pairwise comparisons within the groups for assessment of memory performance. One-sample t test was used for evaluation of object preference statistically different from no discrimination. An unpaired Student t test was used for pairwise comparisons of neurochemical concentrations between WT and p11KO mice in 1H-MRS. Levels of phosphorylated proteins from Western Blot experiments were normalized against total levels with WT control values set to 100%. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 and data are presented as means±s.e.m.

Results

Emotional memory processing in the passive avoidance task

Baseline memory performance of WT, p11HET and p11KO mice

Contextual memory function was examined in a short- or long-term memory setup of the passive avoidance task. Training latencies did not differ (Figure 1b). However, analysis of retention latencies with two-way ANOVA showed effects on delay of testing (F1,36=18.910; P<0.001), with no main effect of genotype (F2,36=1.354; P=0.271) or interaction (F2,36=2.167; P=0.129) (Figure 1c). Post hoc analysis with Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test indicated that while WT groups showed a similar performance when tested at either 5 min or 24 h after training, male p11HET (P<0.05) and p11KO mice (P<0.05) displayed decreasing performance when comparing their respective short- and long-term memory performances (Figure 1c). For matched comparison of latencies at training and retention test, repeated measures two-way ANOVA showed an effect of delay (F1,36=78.327; P<0.001), group (F5,36=4.560; P=0.003) and interaction (F5,36=5.213; P=0.001) (Figures 1b and c). Post hoc analysis with pairwise Bonferroni test showed that increased avoidance behaviors were induced in all groups at the 5 min delay (WT; HET; KO; P<0.001). WT mice showed also an increased avoidance after the 24 h delay (P<0.01), while p11HET and p11KO mice showed no significant increase in step-though latencies if tested 24 h after training. Female p11KO mice displayed similar long-term memory impairments, also with intact short-term memory performance (Supplementary Figures S1b and c). In the NOR memory test, only WT and p11HET mice showed a significant preference for the novel object (Supplementary Figure S2b), with p11HET and p11KO mice spending less time exploring the objects (Supplementary Figure S2c). Total distance covered in the open-field arena did not differ (Supplementary Figure S3a), but p11HET and p11KO mice spent more time in the thigmotaxis zone within 5 cm from the walls in the open-field arena (Supplementary Figure S3b).

Bidirectional effects on memory performance by 5-HT 1B R agonism

5-HT1BR function is regulated by p1122 and the 5-HT1BR modulates emotional memory performance in control mice.17 P11 may thus be involved in the modulation of emotional memory function via 5-HT1BRs. Studies were therefore performed with the 5-HT1BR agonist, CP94253, in WT and p11KO mice. A two-way ANOVA for training latencies showed a main effect of CP94253 (F1,67=6.984; P=0.010), but not genotype (F2,67=0.981; P=0.380) or interaction (F2,67=2.205; P=0.118) (Figure 1d). Newman-Keuls test indicated that CP94253 reduced training latencies in p11KO mice (P<0.05) (Figure 1d). At the retention test, there was an interaction between genotype and CP94253 (F2,67=10.356; P<0.001), with no effect of CP94253 (F1,67=0.001; P=0.972) or genotype (F2,67=3.062; P=0.053). Post hoc analysis showed an impairing effect of CP94253 in WT mice (P<0.01) (Figure 1e). The effects of CP94253 were altered in p11HET mice (P<0.001) and p11KO mice (P<0.01) compared to the response in WT mice. Testing for learning-induced increases of step-though latencies between training and testing, showed significant effects of day (F1,67=114.108; P<0.001), group (F5,67=5.473; P<0.001) and interaction (F5,67=5.794; P<0.001) (Figures 1d and e). Avoidance towards the aversive context were induced in vehicle-treated WT mice (P<0.001), p11HET mice administered with vehicle (P<0.001) or CP94253 (P<0.001) and CP94253-treated p11KO mice (P<0.001) (Figure 1e). To determine whether the facilitatory effect of CP94253 in p11KO mice was specifically caused by activation of 5-HT1BR signaling, and not abnormal off-target effects in the p11KO mice, animals were pretreated with the selective 5-HT1BR antagonist GR127935 before given CP94253. It was found that the memory enhancement by CP94253 (472.0±62.1, P<0.01) versus vehicle-treated controls (197.4±60.6), was fully blocked by co-treatment with GR127935 (225.4±52.9, P<0.001), with no significant effects of the 5-HT1BR antagonist by itself (146.2±33.5) (F3,35=7.715; P<0.001, n=8–13). Since p11 also regulates depression-like changes caused by 5-HT4R stimulation, we examined effects of the 5-HT4R agonist RS67333. In contrast to the p11 genotype-dependent bidirectional effect observed for 5-HT1BR stimulation with CP94253, RS67333 had a positive effect on passive avoidance (Supplementary Figures S3d and e) and NOR (Supplementary Figures S2d and e) performances in both WT and p11KO mice. RS67333 had no effects on open field behavior (Supplementary Figures S3c and d).

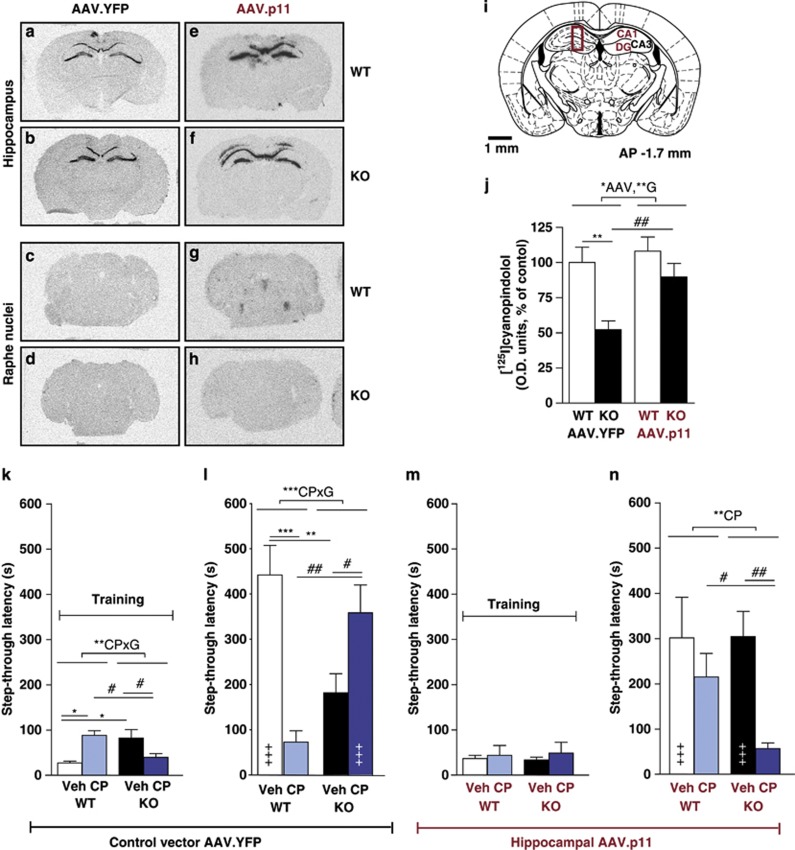

Intrahippocampal AAV mediated p11 gene transfer

To explore the anatomical circuitries involved in p11-mediated regulation of memory performance, we used somatic gene transfer and locally applied AAV to overexpress p11 in the hippocampus. In situ hybridization of control YFP expression (Figures 2a and b, I) and p11 mRNA (Figures 2e and f) in WT and p11KO mice supported a predominant distribution in the targeted CA1 and DG subregions, with some spread to the CA3 layers. While some staining was found in cortical regions, related to the route of administration to the hippocampus, the spread to surrounding regions including the thalamus appeared limited. For the control AAV.YFP vector, no YFP signal was detected at the level of raphe nuclei in WT or p11KO mice (Figures 2c and d). As expected, endogenous expression of p11 mRNA was detected in WT mice, but no p11 mRNA was found in p11KO mice that had received intrahippocampal AAV.p11 (Figures 2g and h), suggesting that the AAV vectors did not appear to be retrogradely transported in 5-HT hippocampal afferents originating in the raphe nuclei. [125I]cyanopindolol autoradiography binding to the 5-HT1BR was used to confirm that restored expression of p11 was functional, i.e. by investigating if overexpression of p11 could upregulate surface levels of the 5-HT1BR.22, 25 An overall effect was found for the AAV vector (F1,44=5.916; P=0.019) and genotype (F1,44=12.450; P=0.001), with no interaction (F1,44=2.445; P=0.125) (Figure 2j). 5-HT1BR-like binding was reduced in p11KO mice receiving control AAV.YFP, compared to WT mice receiving AAV.YFP (P<0.01). After hippocampal AAV-mediated p11 overexpression, the levels of 5-HT1BR-like binding was significantly increased in p11KO mice (P<0.01), whereas hippocampal overexpression of p11 did not result in a significant alteration in WT mice (Figure 2j).

Figure 2.

Reversal of enhanced memory responses to 5-HT1BR stimulation in p11KO mice by hippocampal AAV mediated p11 gene transfer. YFP (a–d) and p11 (e–h) in situ hybridization confirmed predominantly hippocampal transduction of the viral vector in mice receiving AAV.YFP (a–b) and expression of p11 mRNA in mice receiving AAV.p11 (e–f). Autoradiograms from coronal brain sections at the level of raphe nuclei indicate no signs of retrograde transport of AAV in hippocampal 5-HT afferents back to the raphe nuclei (c–d, g–h). Schematic illustration of brain region targeted with AAV (I) as defined and adopted from the mouse brain atlas.53 Restoration of 5-HT1BR–like binding by [125I]cyanopindolol autoradiography in p11KO mice after intrahippocampal injection of AAV.p11 (j). Training (k) and emotional memory (l) performance in control groups of mice given AAV.YFP. CP94253 induced opposite effects on training in WT and P11KO mice (k). Basal impairments of memory performance in vehicle P11KO group and biphasic effect of CP94253 in WT and P11KO (l). The abnormal pharmacological response to CP94253 was normalized in p11KO mice receiving hippocampal AAV.p11 at training (m) and testing (n). Learning-related avoidance was induced in the WT vehicle and P11KO CP94253 groups treated with AAV.YFP control vector (l) and P11KO vehicle treated with AAV.p11 overexpressing vector (n). Data are presented as means±s.e.m. n=6–10 mice per group. +++P<0.001 indicates significant difference between training and testing performances. CP: CP94253 (5-HT1BR agonist), P11KO: p11 knock-out mice, WT: wild type mice, Veh: vehicle injection, G: genotype, AAV: adeno-associated viral vector. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001; #P<0.05; ##P<0.01.

Passive avoidance performance was similar for groups receiving the control vector AAV.YFP (Figures 2k and l) compared to naïve groups of mice without stereotaxic surgery (Figures 1d and e). A two-way ANOVA for training latencies showed an interaction between genotype and CP94253 (F1,30=15.720; P<0.001), but no main effect of genotype (F1,30=0.057; P=0.813) or CP94253 (F1,30=0.523; P=0.475). p11KO mice displayed longer training latencies than WT mice (P<0.05) and CP94253 induced opposite effects (P<0.05) with prolonged training latencies in WT mice (P<0.05) and reduced training latencies in p11KO mice (P<0.05) (Figure 2k). At the memory test, there was an interaction between genotype and CP94253 (F1,30=23.944; P<0.001), with no overall effect of CP94253 (F1,30=2.982; P=0.095) or genotype (F1,30=0.052; P=0.822) (Figure 2l). Basal memory performance differed between WT and p11KO mice treated with vehicle (P<0.01). CP94253 had significant but opposite effects in WT (P<0.001) and p11KO mice (P<0.05).

In groups receiving the p11 vector (AAV.p11), training latencies did not differ (Figure 2m). At the memory test, there was no interaction between genotype and CP94253 (F1,28=2.207; P=0.149), or genotype (F1,28=2.065; P=0.162), but an overall effect of CP94253 (F1,28=9.459; P=0.005) (Figure 2n). Newman-Keuls test showed no differences in memory performance between WT and p11KO mice treated with vehicle (Figure 2n). Notably, CP94253 significantly impaired retention performance in p11KO mice compared to p11KO mice given vehicle (P<0.01) and WT mice given CP94253 (P<0.05) (Figure 2n). Learning-induced effects were observed for day (F1,58=92.83; P<0.001), group (F7,58=4.612; P<0.001) and an interaction between day and groups of mice (F7,58=7.732; P<0.001) (Figures 2k–n). There were significant inductions of avoidance in WT vehicle groups receiving either AAV.YFP (P<0.001) or AAV.p11 (P<0.001), indicating that both WT groups receiving the viruses showed behaviors indicative of successful memory of the PA task. In addition, p11KO mice administered with AAV.YFP showed a significant effect of day when treated with CP94253 (P<0.001) but not when treated with vehicle. On the contrary, p11KO mice administered with AAV.p11 showed significantly increased latency at the memory test, when given vehicle (P<0.001), but not when treated with CP94253, supporting a normalized response after intrahippocampal p11 gene transfer.

Data from the NOR test further supported a role of hippocampal p11 in the bidirectional response to 5-HT1BR signaling on memory processing. CP94253 induced a facilitatory effect on NOR in p11KO mice given the control AAV.YFP vector (Supplementary Figure S4a), normalized by hippocampal p11 overexpression (Supplementary Figure S4c). Object exploration differed between the groups (Supplementary Figures S4b and d) and CP94253 increased open-field distance in WT mice regardless whether they were given AAV.YFP or AAV.p11 (Supplementary Figures S5a and c). In contrast, p11KO mice were resistant to stimulatory effects of CP94253 on distance moved, both in the absence and presence of hippocampal overexpression of p11 (Supplementary Figures S5a and c). Thigmotaxis did not differ between the groups (Supplementary Figures S5b and d).

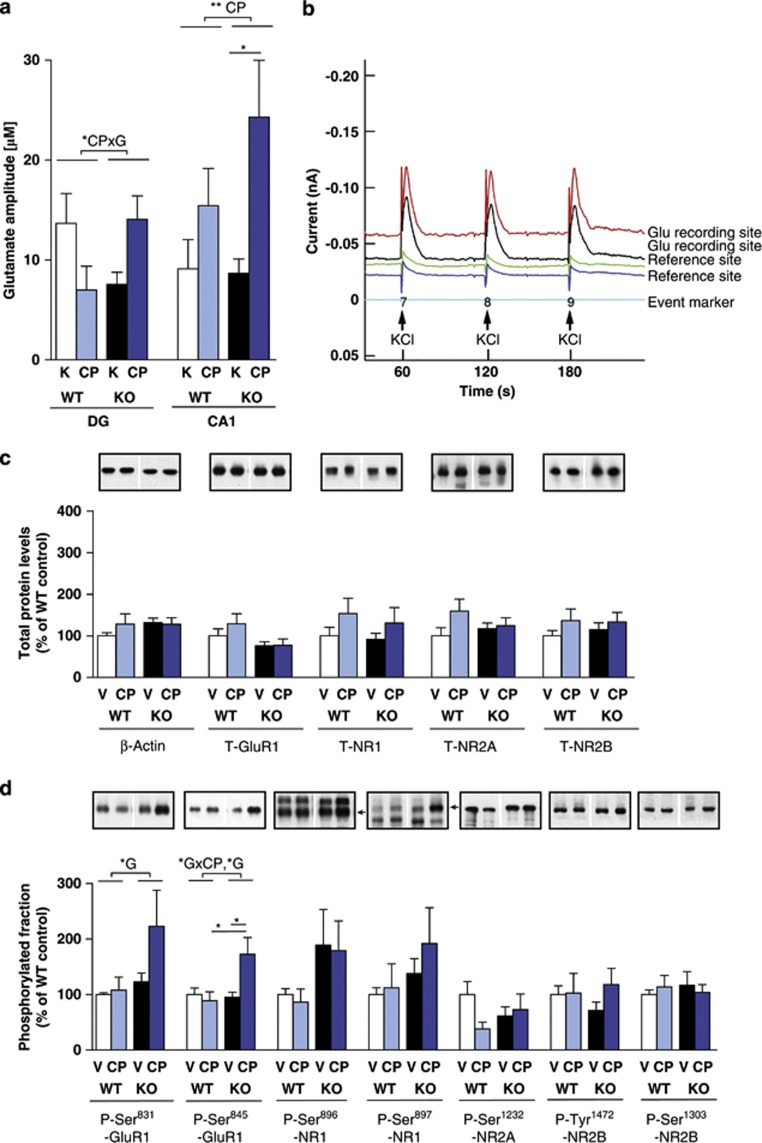

Enzyme-based microelectrode measurements of presynaptic glutamate release

Glutamatergic NMDA receptor-mediated transmission in the dorsal hippocampus is needed for acquisition of the passive avoidance task in mice.28 L-glutamate dynamics were investigated at high spatial and temporal resolutions to address regulation of fast excitatory neurotransmission. Enzyme-based MEA recordings of potassium-evoked L-glutamate release were made in the dorsal hippocampus, with subregions histologically verified as DG and CA1 regions (Supplementary Figures S6c and d). Application of the depolarizing solution (120 mM KCl) evoked robust amplitudes of L-glutamate release in the DG with an interaction between CP94253 and genotype (F1,41=7.072; P=0.011), no main effects of CP94253 (F1,41=0.001; P=0.977) or genotype (F1,41=0.032; P=0.848) (Figure 3a), indicating that the baseline evoked release of glutamate and response to the 5-HT1BR agonist were opposite in DG of WT and p11KO mice (Figure 3a). In the CA1 region, no interaction was found for CP94253 and genotype (F1,33=1.376; P=0.249), but a main effect of CP94253 (F1,33=7.657; P=0.009) and not genotype (F1,33=1.126; P=0.296). Post hoc analysis showed a stimulatory effect of 10 μM of CP94253 compared to vehicle in KO mice (P<0.05), with no significant stimulation of the 5-HT1BR agonist in WT mice (Figure 3a). No differences were found for T80, which is the time between peak maximum amplitude and 80% decrease of the glutamate levels, in the hippocampal DG and CA1 subregions (Supplementary Figure S6e) or mean volume of locally applied KCl (Supplementary Figure S6f). Taken together, enzyme-based MEA measurements of evoked L-glutamate release indicate increased presynaptic release of glutamate by the 5-HT1BR agonist CP94253 in the hippocampus of p11KO mice.

Figure 3.

Increased pre- and postsynaptic hippocampal glutamate neurotransmission by 5-HT1BR stimulation in p11KO mice. Glutamate-oxidase enzyme based MEA recordings of potassium-evoked glutamate release amplitudes in hippocampal CA1 and DG subregions of anesthetized mice (a). Real-time in vivo amperometric responses of reproducible glutamate dynamics recorded at 2 Hz, with glutamate recording sites (corresponding to responses in red and black) and sentinel or reference sites (corresponding to responses in blue and green) (b). Event markers indicated by arrows mark depolarization-induced responses evoked by 120 mM KCl with and without co-administration of 10 μM of CP94253 (b), with 60 s between each local application of KCl. For glutamate release amplitudes in the DG, an interaction was found between CP94253 and genotype (a). In the CA1, CP94253 resulted in a higher KCl-evoked glutamate release amplitude in P11KO mice compared to baseline depolarization-evoked release of glutamate in P11KO mice (a). Histograms quantifying total protein levels and phosphorylated form of the protein normalized to the total level of the protein (c–d) in the hippocampus. Representative western blots are shown above each histogram. Genotype-dependent effects were found for phosphorylation at Ser831 of the GluR1 subunit and increased phosphorylation at Ser845-GluR1 by CP94253 in p11KO mice (d). Data are presented as means±s.e.m. (a) 3–5 reproducible peaks with n=10–14 (DG) and 8–10 (CA1) recordings per group. (c–d) n=5–6. CA1: cornu ammonis 1 of hippocampus, DG: dentate gyrus of hippocampus, CP: CP94253 (5-HT1BR agonist), G: genotype, P11KO: p11 knock-out mice, WT: wild type mice, K: KCL (potassium chloride, 120 mM), MEA: microelectrode array. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Western Blotting of total protein and phosphorylation levels

Possible postsynaptic consequences of the increased glutamate release found in p11KO mice were investigated by hippocampal assessment of phosphorylation states of glutamate AMPAR and NMDAR, predominantly located postsynaptically to glutamatergic terminals. Immunoblotting showed no alterations in total protein levels of subunits of the AMPAR or NMDAR (Figure 3c). At phospho-Ser831-GluR1 (a protein kinase C/CaMKII site) of the AMPAR, there was a main effect of genotype (F1,18=4.458; P=0.049), with no overall effect of CP94253 (F1,18=2.720; P=0.116) or interaction (F1,18=1.996; P=0.175) (Figure 3d). GluR1 subunits also showed altered phosphorylation at Ser845 (a protein kinase A site) indicated by an effect on a two-way ANOVA by genotype (F1,20=4.491; P=0.047) and interaction (F1,20=5.632; P=0.028) with no overall effect of treatment (F1,20=3.135; P=0.092). Post hoc analysis showed a significantly increased phosphorylation at Ser845-GluR1 by CP94253 compared to both vehicle in p11KO mice (P<0.05) and CP94253 treated WT mice (P<0.05) (Figure 3d). The potentiation of glutamatergic receptor signaling at procognitive sites on AMPA receptors, i.e. coupled to downstream signaling pathways that have been implicated in memory processing and synaptic plasticity, are consistent with the behavioral findings of reversed memory function by CP94253 in p11KO mice (Figures 1e and 2l). In contrast, no differences were found on phosphorylation of the NMDA receptor subunits at Ser896-NR1 (PKC site), Ser897-NR1 (PKA site), Ser1232-NR2A (cdk5 site), Ser1303-NR2B (CaMKII site) or Tyr1472-NR2B (SRC tyrosine kinase site) (Figure 3d).

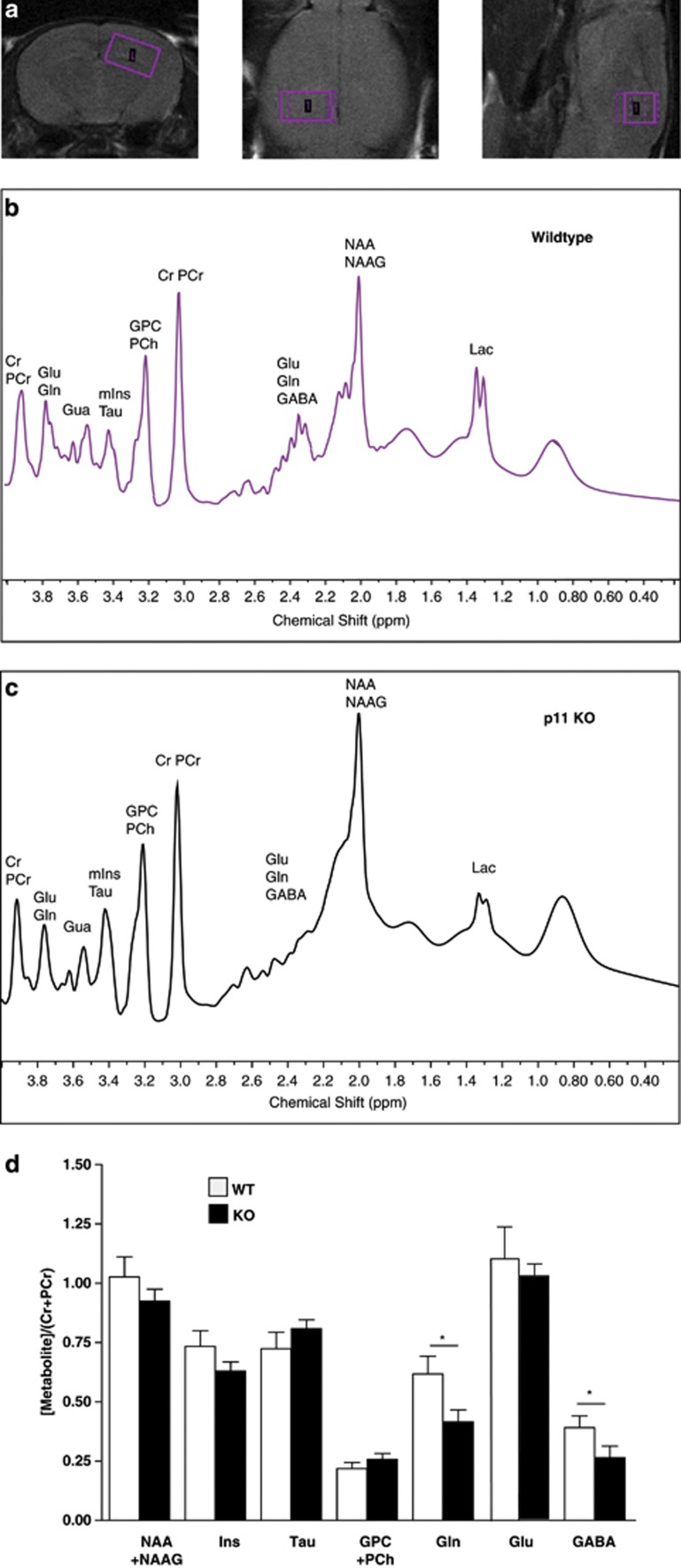

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

In vivo neurochemical magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) measures revealed reduced relative concentration of glutamine (t13=2.301; P<0.05, Student's t test) and GABA (t13=1.822; P<0.05, Student's t test) in p11KO compared to WT mice (Figure 4d), with no differences found of other studied neurochemicals, including glutamate. The decreased levels of glutamine could affect both glutamate and GABA, since glutamine is the precursor for both these amino acids, but these findings indicate intact glutamate concentrations and reduced metabolic concentrations of GABA. The decreased hippocampal levels of inhibitory neurotransmitter in p11KO mice (Figure 4d) are in line with the evidence for increased excitability in p11KO mice in response to 5-HT1B stimulation on pre- (Figure 3a) and postsynaptic (Figure 3d) measures of glutamatergic excitatory neurotransmission.

Figure 4.

Reduced hippocampal inhibitory transmitter detected by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS). Representative MRI (magnetic resonance image) featuring coronal, axial and sagital slices through a mouse brain (a). Placement of the voxel, the volume of interest (VOI) sized 3.0 × 1.8 × 1.8 mm3, for spectroscopy in the hippocampus indicated by the box. 1H-MR spectra acquired from the voxel centered in the hippocampus of WT (b) and p11KO mouse (c). Mean neurochemical concentration in WT (white bars) and p11KO mice (filled bars) (d). Relative concentrations of glutamine and GABA were reduced in the hippocampus of p11KO mice when compared to WT mice. Data are presented as means±s.e.m. for WT (n=7); P11KO (n=8). NAA+NAAG: N-Acetylaspartate+N-Acetylaspartatylglutamate, Ins: Inositol, Tau: Taurine, Glu: Glutamate, Gln: Glutamine, GABA; gamma-amino butyric acid, GPC+PCh: GlyceroPhosphocholine+Phosphocholine, WT: wild type mice, P11KO: p11 knock-out mice. *P<0.05.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates an unexpected bidirectional action of a 5-HT1BR agonist on rodent emotional memory function, determined by the hippocampal levels of p11. Emerging data suggest a role for serotonin and its receptors in effects of antidepressants on emotional memory processing, which is preceding mood alterations both in healthy volunteers and depressed individuals.10, 11 From a translational view, the major findings of these studies support that serotonin is critically implicated in emotional memory processes also in animal models.15

p11KO mice carry genetic predisposition for depression-like symptoms and displayed preserved short- but impaired long-term memory function and an atypical stimulatory 5-HT1BR agonist behavioral response. Establishment of long-term memory in the passive avoidance task relies on complex associations of multisensory cues, i.e. hippocampal NMDAR-dependent contextual representations.28 The aversive stimuli used to motivate learning involve the amygdala and sensory systems receiving parts of the multisensory cues, processing of the information in the thalamus and corticohippocampal circuitries including the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortices.15, 28, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 To better understand the anatomical circuitries by which p11 modulates emotional memory performance, AAV-mediated gene transfer was used to overexpress p11 in hippocampus.25 Intrahippocampal AAV.p11 resulted in increased p11 locally in hippocampus, but not in the raphe nuclei thus distinguishing effects of p11 in serotonergic neurons to effects in postsynaptic serotonoceptive neurons of the hippocampus (Figure 5). Interestingly, after overexpression of hippocampal p11, the 5-HT1BR agonist impaired memory in p11KO mice resembling the normal response in WT mice. Overexpression of p11 in WT mice did not affect baseline performance but attenuated the amnesic effect of the 5-HT1BR agonist, indicating that the relationship between hippocampal p11 and 5-HT1BR agonist response is not linear, but rather follows an inverted U-shaped curve. To examine whether the memory dysfunction in p11KO mice was restricted to the passive avoidance task, we also studied effects in NOR, a test based on the premise that rodents will explore a novel object more than a familiar one, but only if they remember the familiar object (see Supplementary Information). Similarly to the results in the passive avoidance task, overexpression of p11 normalized the atypical 5-HT1BR agonist response in p11KO mice. Since 5-HT1BRs and p11 are located on both serotonergic raphehippocampal neurons and serotonoceptive hippocampal neurons, the p11 gene transfer data indicates that the effects of p11 on basal and 5-HT1BR-mediated modulation of memory processing occurs primarily in postsynaptic serotonoceptive neuron in the hippocampus (Figure 5).

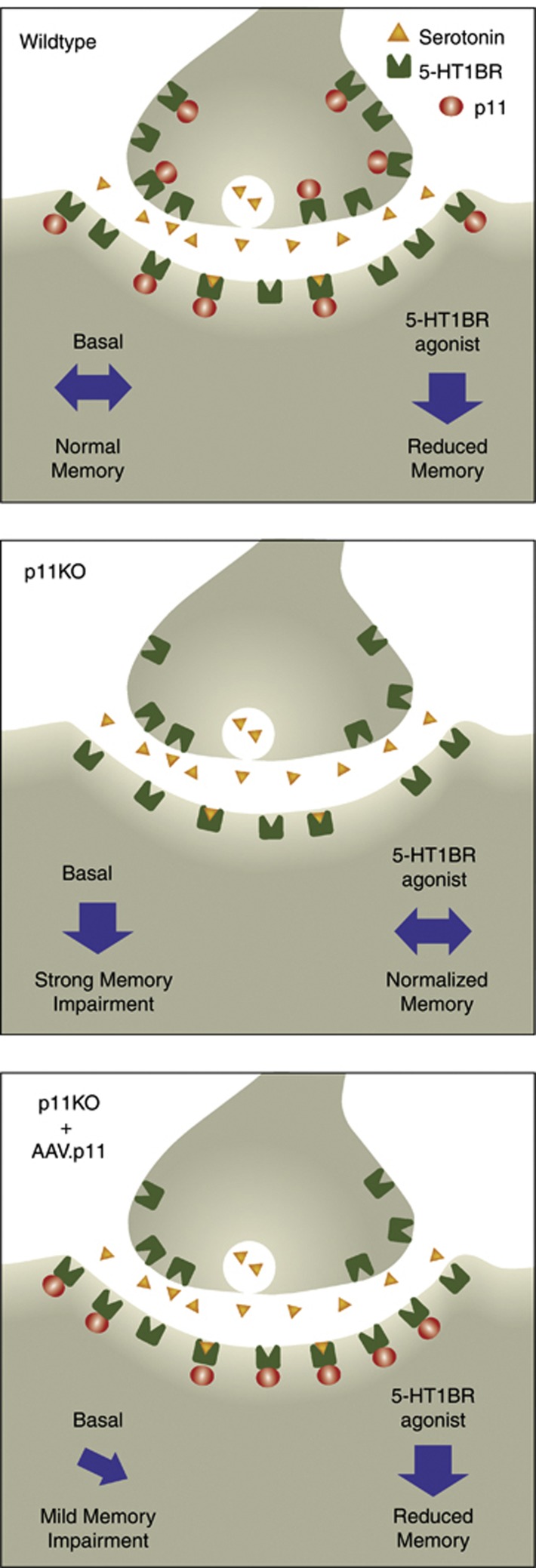

Figure 5.

Simplified schematic illustration of how 5-HT1BR modulation of emotional memory processing is gated by p11 in the hippocampus. p11 is normally expressed in serotonergic raphe-hippocampal neurons and in several different types of serotonoceptive hippocampal neurons (upper), as described in more detail in the discussion. Wildtype mice display normal memory function under basal conditions (upper left). Treatment with the 5-HT1BR agonist CP94253 to wildtype mice causes an amnesic effect with reduced memory performance (upper right). In p11KO mice, emotional memory impairments were found at baseline (middle left). 5-HT1BR agonist treatment to p11KO mice induce a facilitation of memory function, resulting in normalization of memory performance (middle right). Intrahippocampal AAV.p11 increases p11 in serotonoceptive postsynaptic hippocampal neurons, but not in serotoninergic neurons originating from the raphe nuclei (lower). Intrahippocampal p11 gene transfer in p11KO mice results in a mild memory impairment under basal conditions (lower left). In p11 KO mice with intrahippocampal AAV.p11, 5-HT1BR agonist treatment reduced memory (lower right) similar to its effects in wildtype mice, but drastically different from 5-HT1BR agonist treatment in non-transduced p11KO mice.

A series of experiments aimed to investigate the mechanism(s) whereby 5-HT1BRs and p11 regulate hippocampal neurotransmission. Hippocampal p11 is expressed in glutamatergic pyramidal cells of the CA1 and CA3 areas, glutamatergic granular cells of the dentate gyrus and in different subpopulations of GABAergic interneurons.22, 24, 42 p11 mRNA is also expressed in neuronal pathways innervating hippocampus such as the raphe nuclei and medial septum cholinergic neurons.22 5-HT1BRs are widely expressed within hippocampal circuitries as well as in the abovementioned interconnected regions.21, 22, 43 Within the hippocampus, there is some enrichment of 5-HT1BRs in pyramidal cells of the CA1 area, inhibiting the release of glutamate at terminal projections from CA1 neurons in subiculum and at axon collaterals to neighboring CA1 pyramidal cells, reducing excitatory transmission from local excitatory networks.44 In contrast, it has also been convincingly shown that inhibition of glutamate release by stimulation of 5-HT1BRs on axon collaterals from CA1 pyramidal cells, via CCK GABA interneurons and an inhibitory feedback loop, increase the firing of pyramidal CA1 neurons.45 Moreover, recent data also indicate the presence of 5-HT1BRs on dendrites of hippocampal neurons, particularly granular cells of the dentate gyrus.46 The current data imply that hippocampal 5-HT1BRs are of at least two types; 5-HT1BRs regulated by p11 and suppressing emotional memory processing, and other 5-HT1BRs that are independent of p11 and enhance emotional memory (Figure 5).

Since the anatomical data indicate that changes in p11 expression may modulate hippocampal glutamate neurotransmission by several mechanisms, we studied effects on both pre- and postsynaptic measures. In view of the methodological problems of measuring neuronal release of glutamate by microdialysis43, 47 we used a novel enzyme-based microelectrode technique that enables second-by-second in vivo glutamate measures.33 Using this technology, KCl evoked glutamate release was induced by the 5-HT1BR agonist, CP94253, in the dentate gyrus and the CA1 subregions of the hippocampus in p11KO mice.

Correspondingly, increased phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of the AMPA receptor in p11KO mice indicated that the 5-HT1BR agonist, CP94253, stimulated glutamatergic transmission in p11KO mice. Since the GluR1 subunit is post-synaptic it seems likely that the increased phosphorylation at the examined sites, Ser831 and Ser845, correlates with enhanced synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation.48 It is notable that phosphomutant GluR1 mice lacking phosphorylatable Ser831 and Ser845-residues perform worse in a contextual fear conditioning paradigm.49

To increase our understanding of the global neurochemistry of hippocampus in p11KO mice, a comparative 1H-MRS examination was performed. It turned out that the global relative concentrations of glutamate were not significantly changed, but that p11KO mice showed reductions of hippocampal glutamine and GABA levels. In accordance, depressed individuals have alterations in glutamate and GABA50, 51 and reductions in the number of calbindin-positive GABAergic interneurons.52 A reduced GABAergic tone in hippocampus in p11KO mice is consistent with the fact that several classes of GABAergic interneurons express very high levels of p1142 but could also involve changes on several adapter proteins to p11, like the ion channels (e.g. acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC)-1) and intracellular enzymes (e.g. phospholipase A2, tPA) or its principal partner annexin 2.23 The overall hippocampal reduction of GABAergic tone may indirectly contribute to enhanced excitatory glutamate neurotransmission and is consistent with the unexpected 5-HT1BR-mediated potentiation of pre- and post-synaptic measures of glutamate transmission and the cognitive enhancing effects of a 5-HT1BR agonist in p11KO mice.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence for an unforeseen dynamic modulation of memory processing by the 5-HT1BR, which is under control of p11. The experimental evidence support an important role of glutamatergic mechanisms by which the 5-HT1BR can mediate biphasic modulation of memory performance. Taken together, this study emphasizes a multifaceted regulation of cognition by the 5-HT1BR and the importance of using relevant disease models when evaluating 5-HT1BR ligands for the treatment of cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Nicoletta Schintu, Saurav Shrestha and Junfeng Yang for their excellent experimental and technical support, and Dr Stefan Brené and Dr Jeremy Young at the Experimental Magnetic Resonance Center at Karolinska Institutet. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, Söderberg's stiftelse and Karolinska Institutet Faculty Funds (KID) (TME and AA), Quanteon, LLC and USPHS grant DA017186 (KNH and GAG), The Fischer Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation (PS and PG), W81XWH-09-1-0402 (PG), NIH MH090963 (PG), W81XWH-09-0381(MGK) and the European Union Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement no. PEOPLE-ITN-2008-238055 (BrainTrain).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Molecular Psychiatry website (http://www.nature.com/mp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Clark L, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. Neurocognitive mechanisms in depression: implications for treatment. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen GM, Campbell S, McEwen BS, Macdonald K, Amano S, Joffe RT, et al. Course of illness, hippocampal function, and hippocampal volume in major depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1387–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337481100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roiser JP, Levy J, Fromm SJ, Nugent AC, Talagala SL, Hasler G, et al. The effects of tryptophan depletion on neural responses to emotional words in remitted depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Lucki I, Drevets WC. 5-HT(1A) receptor function in major depressive disorder. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;88:17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodl T, Schaub A, Banac S, Charypar M, Jäger M, Kümmler P, et al. Reduced hippocampal volume correlates with executive dysfunctioning in major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:316–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig A, Littmann E, Bauer M. Neurocognitive impairment and dementia in mood disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;4:373–382. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.4.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GM. Symptom relief and facilitation of emotional processing. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;Suppl 4:S710–S715. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle A, Browning M, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ. A cognitive neuropsychological model of antidepressant drug action. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35:1586–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ. Serotonin and emotional processing: does it help explain antidepressant drug action. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Efficacy markers in depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;9:1148–1158. doi: 10.1177/0269881110367722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambeth A, Blokland A, Harmer CJ, Kilkens TO, Nathan PJ, Porter RJ, et al. Sex differences in the effect of acute tryptophan depletion on declarative episodic memory: a pooled analysis of nine studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:516–529. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieben CK, van Oorsouw K, Deutz NE, Blokland A. Acute tryptophan depletion induced by a gelatin-based mixture impairs object memory but not affective behavior and spatial learning in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2004;151:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida S, Umeeda H, Kitamoto A, Masushige S, Kida S. Chronic reduction in dietary tryptophan leads to a selective impairment of contextual fear memory in mice. Brain Res. 2007;1149:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren SO, Eriksson TM, Elvander-Tottie E, D'Addario C, Ekström JC, Svenningsson P, et al. The role of 5-HT(1A) receptors in learning and memory. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:54–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åhlander-Lüttgen M, Madjid N, Schött PA, Sandin J, Ögren SO. Analysis of the role of the 5-HT1B receptor in spatial and aversive learning in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1642–1655. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson TM, Madjid N, Elvander-Tottie E, Stiedl O, Svenningsson P, Ögren SO. Blockade of 5-HT 1B receptors facilitates contextual aversive learning in mice by disinhibition of cholinergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark KL, Hen R. Knockout Corner. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2:145–150. doi: 10.1017/S146114579900142X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt RA, Hiroi R, Mackenzie SM, Robin NC, Cohn A, Kim JJ, et al. Serotonin 1B autoreceptors originating in the caudal dorsal raphe nucleus reduce expression of fear and depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrough JW, Henry S, Hu J, Gallezot JD, Planeta-Wilson B, Neumaier JF, et al. Reduced ventral striatal/ventral pallidal serotonin1B receptor binding potential in major depressive disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;213:547–553. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1881-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisman H, Du L, Palkovits M, Faludi G, Kovacs GG, Szontagh-Kishazi P, et al. Serotonin receptor subtype and p11 mRNA expression in stress-relevant brain regions of suicide and control subjects. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33:131–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson P, Chergui K, Rachleff I, Flajolet M, Zhang X, El Yacoubi M, et al. Alterations in 5-HT1BR function by p11 in depression-like states. Science. 2006;311:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1117571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson P, Greengard P. p11 (S100A10)—an inducible adaptor protein that modulates neuronal functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner-Schmidt JL, Flajolet M, Maller A, Chen EY, Qi H, Svenningsson P, et al. Role of p11 in cellular and behavioral effects of 5-HT4 receptor stimulation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1937–1946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5343-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander B, Warner-Schmidt J, Eriksson T, Tamminga C, Arango-Lievano M, Ghose S, et al. Reversal of depressed behaviors in mice by p11 gene therapy in the nucleus accumbens. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:54ra76. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Andren PE, Greengard P, Svenningsson P. Evidence for a role of the 5-HT1BR and its adaptor protein, p11, in L-DOPA treatment of an animal model of Parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2163–2168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711839105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan NA, Holick Pierz KA, Masten VL, Waeber C, Ansorge M, et al. Chronic reductions in serotonin transporter function prevent 5-HT1B-induced behavioral effects in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarendse PJ, van Grootheest G, Jansen RF, Pieneman AW, Ögren SO, Verhage M, et al. Differential involvement of the dorsal hippocampus in passive avoidance in C57bl/6J and DBA/2J mice. Hippocampus. 2008;18:11–19. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsson P, Le Moine C, Aubert I, Burbaud P, Fredholm BB, Bloch B. Cellular distribution of adenosine A2A receptor mRNA in the primate striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1998;399:229–240. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980921)399:2<229::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson TM, Delagrange P, Spedding M, Popoli M, Mathé AA, Ögren SO, et al. Emotional memory impairments in a genetic rat model of depression: involvement of 5-HT/MEK/Arc signaling in restoration. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;2:173–184. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X, Pal R, Hascup KN, Wang Y, Wang WT, Xu W, et al. Transgenic expression of Glud1 (glutamate dehydrogenase 1) in neurons: in vivo model of enhanced glutamate release, altered synaptic plasticity, and selective neuronal vulnerability. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13929–13944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4413-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hascup KN, Hascup ER, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Second-by-second measures of L-glutamate in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of freely moving mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:725–731. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TC, Grandy DK, Gerhardt GA, Glaser PE. Decreased dopamine D4 receptor expression increases extracellular glutamate and alters its regulation in mouse striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:436–445. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JM, Öberg J, Brené S, Coppotelli G, Terzioglu M, Pernold K, et al. High brain lactate is a hallmark of aging and caused by a shift in the lactate dehydrogenase A/B ratio. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20087–20092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008189107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE, Muller J. Emotional memory and psychopathology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1719–1726. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RD, Saddoris MP, Bucci DJ, Wiig KA. Corticohippocampal contributions to spatial and contextual learning. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3826–3236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0410-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill L, McGaugh JL. Mechanisms of emotional arousal and lasting declarative memory. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:294–299. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh JL. The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Fanselow MS. The neuroanatomical and neurochemical basis of conditioned fear. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:743–760. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC, Bouton ME. Hippocampus and context in classical conditioning. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland M, Warner-Schmidt J, Greengard P, Svenningsson P. Neurogenic effects of fluoxetine are attenuated in p11 (S100A10) knockout mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XJ, Wang FH, Stenfors C, Ögren SO, Kehr J. Effects of the 5-HT1BR antagonist NAS-181 on extracellular levels of acetylcholine, glutamate and GABA in the frontal cortex and ventral hippocampus of awake rats: a microdialysis study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007a;17:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlinar B, Falsini C, Corradetti R. Pharmacological characterization of 5-HT1B receptor-mediated inhibition of local excitatory synaptic transmission in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:71–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterer J, Stempel AV, Dugladze T, Földy C, Maziashvili N, Zivkovic AR, et al. Cell-type-specific modulation of feedback inhibition by serotonin in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8464–8475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6382-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peddie CJ, Davies HA, Colyer FM, Stewart MG, Rodríguez JJ. Dendritic colocalisation of serotonin1B receptors and the glutamate NMDA receptor subunit NR1 within the hippocampal dentate gyrus: an ultrastructural study. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;36:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman W, Westerink BH. Brain microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: what does it signify. Synapse. 1997;27:242–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199711)27:3<242::AID-SYN9>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Takamiya K, Han JS, Man H, Kim CH, Rumbaugh G, et al. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit is required for synaptic plasticity and retention of spatial memory. Cell. 2003;112:631–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Real E, Takamiya K, Kang MG, Ledoux J, Huganir RL, et al. Emotion enhances learning via norepinephrine regulation of AMPA-receptor trafficking. Cell. 2007b;131:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, Wu YT, Appel M, Rothman DL, et al. Subtype-specific alterations of GABA and glutamate in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:705e713. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher B, Shen Q, Sahir N. The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:383–406. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, O'Dwyer G, Teleki Z, Stockmeier CA, Miguel-Hidalgo JJ. GABAergic neurons immunoreactive for calcium binding proteins are reduced in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:471–482. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KBJ, Paxinos G. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic coordinates. Academic: San Diego; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.