Abstract

Microtexture and chemistry of implant surfaces are important variables for modulating cellular responses. Surface chemistry and wettability are connected directly. While each of these surface properties can influence cell response, it is difficult to decouple their specific contributions. To address this problem, the aims of this study were to develop a surface wettability gradient with a specific chemistry without altering micron scale roughness and to investigate the role of surface wettability on osteoblast response. Microtextured sandblasted/acid-etched (SLA, Sa = 3.1 μm) titanium disks were treated with oxygen plasma to increase reactive oxygen density on the surface. At 0, 2, 6, 10, and 24 h after removing them from the plasma, the surfaces were coated with chitosan for 30 min, rinsed and dried. Modified SLA surfaces are denoted as SLA/h in air prior to coating. Surface characterization demonstrated that this process yielded differing wettability (SLA0 < SLA2 < SLA10 < SLA24) without modifying the micron scale features of the surface. Cell number was reduced in a wettability-dependent manner, except for the most water-wettable surface, SLA24. There was no difference in alkaline phosphatase activity with differing wettability. Increased wettability yielded increased osteocalcin and osteoprotegerin production, except on the SLA24 surfaces. mRNA for integrins α1, α2, α5, β1, and β3 was sensitive to surface wettability. However, surface wettability did not affect mRNA levels for integrin α3. Silencing β1 increased cell number with reduced osteocalcin and osteoprotegerin in a wettability-dependent manner. Surface wettability as a primary regulator enhanced osteoblast differentiation, but integrin expression and silencing β1 results indicate that surface wettability regulates osteoblast through differential integrin expression profiles than microtexture does. The results may indicate that both microtexture and wettability with a specific chemistry have important regulatory effects on osseointegration. Each property had different effects, which were mediated by different integrin receptors.

Keywords: Wettability, Oxygen plasma, Chitosan, Titanium, Osteoblast, Integrin

1. Introduction

Titanium surface roughness, energy, chemical composition, and wettability regulate osteoblast response through interaction between the outermost implant surfaces and bone [1–4]. Osteoblasts display a more differentiated phenotype on complex micron-/submicron-scale rough surfaces than on relatively smooth titanium surfaces [3,5]. Materials with different chemistries, including tissue culture polystyrene [TCPS], pure titanium or titanium alloy with oxide layer, and hydroxyapatitecoated titanium surfaces, yield different cellular responses through variations in protein adsorption and integrin expression [6–8].

Surface wettability has been recognized as an important factor to control the dynamic interaction at the interface between an implanted surface and serum or blood in vitro and in vivo, respectively [9,10]. Poor water-wettable surfaces support more protein adsorption than good water-wettable surfaces [11]. Blood plasma coagulation occurs slowly on poor water-wettable surfaces while blood comes quickly into contact with good water-wettable surfaces, efficiently activating the coagulation cascade [10]. Consequently, fast stabilization can shorten healing time and increase production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [12,13]. Titanium surfaces with both excellent wettability and micron-/submicron-scale complex roughness can synergistically enhance osseointegration through fast blood clot stabilization and shortened wound healing time [14].

Osteoblasts do not directly interact with the surface of a biomaterial, but instead they interact with adsorbed proteins from culture medium in vitro or physiological fluids in vivo [15]. Integrins, heterodimeric transmembrane receptors with non-covalently bound α and β subunits, are sensitive to the adsorbed matrix proteins, and serve as a bridge between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and actin cytoskeleton [15–18]. ECM-integrin-cytoskeleton/signal protein kinases are able to transmit the signals both inside-out and outside-in directions and both pathways of signal transduction can mediate cell behavior [19]. Integrin expression can be regulated by surface wettability [16] and osteoblast maturation and local factor production are dependent on specific integrin signaling [18]. However, the mechanism of how surface wettability itself can regulate the interaction at the interface and modulate cellular response is still not fully addressed.

Surface wettability has been modified through several methods including self-assembled monolayers, functional chemical species, multilayers with oppositely charged polymers, and topographical changes [20,21]. We previously demonstrated that surface wettability can be modified by polyelectrolyte coatings applied to sandblasted/acid-etched (SLA) surfaces [4]. This study showed that osteoblasts cultured on chitosan-coated rough surfaces exhibited increased production of osteocalcin, a late marker of osteoblast differentiation, and osteoprotegerin, a local factor produced by osteoblasts to inhibit osteoclast differentiation [22], compared to SLA surfaces without coating or coated with either poly(l-glutamic acid) or poly(l-lysine).

Surface chemistry and wettability are directly connected. While each of these surface properties can affect cell response differently, it is difficult to distinguish the effect of individual surface properties on cell response [4] since changing one property often changes others. To address this limitation, the aims of this study were to develop a surface wettability gradient without changing chemistry and micron scale roughness and to investigate the role of surface wettability on osteoblast response. Furthermore, effects of the surface wettability gradient on integrin expression were examined.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Titanium substrates

Commercially pure titanium disks (Ø 15 mm × 1 mm, grade 2, Institut Straumann AG, Basel, Switzerland) were used in this study. The titanium disks were treated by sand-blasting followed by an acid-etch to generate a microtextured surface (SLA, Sa = 3.1 μm), as described previously [4].

2.2. Preparation of chitosan nanofilms

A 1.5 mg/ml chitosan (MW = 125,000–350,000 g/mol, deacetylation degree 80–89%, medical grade, NovaMatrix, Drammen, Norway) solution was prepared in 0.1 M acetic acid (reagent grade, Sigma–Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and filtered through a sterilized polytetrafluorethylene (PTFE) filter (pore size 0.2 μm, Nalgene®, Rochester, NY). To generate a surface wettability gradient on the SLA surface, the disks were treated with oxygen plasma (PDC-32G, Harrick Plasma, NY, USA) for 3 min on each side to generate an oxygen density gradient [23].

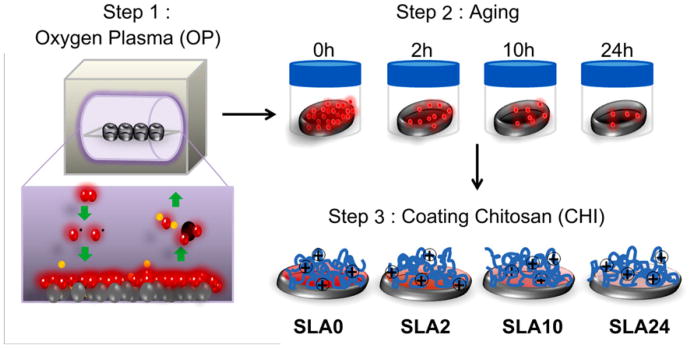

All surface preparation was performed in a sterile environment (cell culture hood) using aseptic techniques. After removal from the plasma, the disks were placed immediately into centrifuge tubes (conical, 50 ml) and the surfaces aged in air at room temperature for 0, 2, 6, 10, and 24 h. At each time point a set of surfaces were coated with chitosan. To do this, the disks were transferred from centrifuge tubes to 24 well plates where they were coated with chitosan (500 μl) for 30 min, rinsed 3 times for 10 min in ultrapure water and dried for 24 h in a cell culture hood. Modified SLA surfaces are denoted as SLA/h in air after removal from the plasma (i.e., SLA10 represents SLA surfaces treated by oxygen plasma and aged for 10 h before chitosan coating). Unprocessed SLA surfaces were used as a control. Surface preparation is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of surface modification process. Step 1: SLA surfaces were treated with oxygen plasma for 3 min per each side. Step 2: oxygen plasma treated SLA surfaces were stored in a closed container for 0, 2, 10, and 24 h. Step 3: chitosan was coated on surfaces for 30 min and excess chitosan removed by rinsing.

2.3. Surface characterization

Wettability of modified SLA surfaces was determined by measuring contact angle with a Ramé-Hart goniometer (model 250-F1, Mountain Lakes, NJ). Consistent volumes (2 μl) of ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm, Millipore Milli-Q system) were used as a droplet. Dropped liquid images were recorded and analyzed with the DROP-image CA software package (Ramé-Hart Instrument Co.).

Surface roughness was measured by using a LEXT 3D material confocal laser microscope (CLM, 50 × objective, Olympus America Inc., PA, USA) with a 100 μm threshold. Roughness results were analyzed with the LEXT OLS4000 software provided by Olympus. The surface morphology was obtained using an Ultra 60 field emission (FE) scanning electron microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss SMT Ltd., Cambridge, UK) with accelerating voltage (5 kV) and gold coating with Hummer 5 Gold Sputterer (thickness ≈ 10 nm).

The amount of adsorbed chitosan adsorbed on each surface was calculated by determining the amount of chitosan remaining in the starting solution after coating the substrate. The chitosan content of the solution at the start and after coating were measured by UV–Vis spectrophotometry (λnm = 230), using 0.1 M acetic acid as the background control.

Surface chemistry was analyzed by Thermo K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, MA, USA) equipped ultra high vacuum (10−9 Torr or lower) and with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (hv = 1486.6 eV photons) at a 90° takeoff angle. The Thermo Advantage 4.43 software package (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to evaluate XPS spectrum results. Three random spots per three different specimens were used to characterize contact angle, CLM, and XPS.

The thickness of thin films can be measured by using several methods including ellipsometry, AFM, and XPS. In this study, we used the XPS depth profile to estimate chitosan film thickness because both ellipsometry and AFM were not suitable for SLA micron-/submicron-rough surfaces. Because the SLA surface was not smooth like the more commonly used silicon wafers, there was a chance that detection sensitivity would be decreased due to scattering. For this reason, we used the amount of N detected on the surface as an indicator of adsorbed chitosan. It was not possible to make a definitive determination of the boundary between the titanium oxide layer and chitosan because oxygen, titanium, and carbon were detected in all surfaces.

2.4. Cell response

Cell responses on wettability gradient surfaces were performed using human osteoblast-like MG63 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). Cells were plated on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS), SLA, SLA0, SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 surfaces at a density of 10,000 cells/cm2. TCPS surfaces were used as an internal standard. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modification of Eagle's medium (Cellgro®, Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Waltham, MA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity. Cell number was counted in all cultures 24 h after confluence on TCPS. To collect all cells on the rough titanium surfaces, cells were released by two sequential 10 min incubations in 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. Cells were counted using Z1 Particle Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and cell number was used to normalize immunoassay results. Cellular alkaline phosphatase specific activity was measured by determining p-nitrophenol (pNP) release from p-nitrophenylphosphate (pNPP) at pH 10.2 in the cell lysate and normalized to total protein content (Macro BCA Protein Assay Kit, Pierce). Osteocalcin levels in the conditioned media were determined by radioimmunoassay (Human Osteocalcin RIA Kit, Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA). Osteoprotegerin, VEGF, and latent and active transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β1) were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (DuoSet, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All methods have been described previously [24].

2.5. Integrin expression

MG63 cells were plated on TCPS, SLA, or chitosan-modified SLA surfaces and cultured as described above. At confluence on TCPS, cultures were incubated with fresh medium for 12 h. RNA was isolated using TriZol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. 500 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA (High Capacity cDNA Kit, Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The resulting cDNA was used in real-time PCR reactions with Power@ Sybr Creen (Applied Biosystems). Starting mRNA quantities for integrin subunits α1, α2, α3, α5, β1 and β3 were calculated using standard curves generated from known dilutions of MG63 cells and normalized to expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Gene specific primers (Table 1) were designed using Beacon Designer Software and synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for real-time PCR analysis of gene expression.

| Gene | Primer | sequence | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | R | GCG AGC ACA GGA AGA AGC | NM_002046.3 |

| F | GCT CTC CAG AAC ATC ATC C | ||

| ITGA1 | R | TGC TTC ACC ACC TTC TTG | NM_181501.1 |

| F | CACTCGTAAATGCCAAGAAAAG | ||

| ITGA2 | R | TAGAACCCAACACAAAGATGC | NM_002203 |

| F | ACT GTT CAA GGA GGA GAC | ||

| ITGA3 | R | GTAGTGGTGAGTGAGAAGTGG | NM_002204.2 |

| F | GGAACAAAGACAGGCAAACG | ||

| ITGA5 | R | GGT CAA AGG CTT GTT TAG G | NM 002205 |

| F | ATC TGT GTG CCT GAC CTG | ||

| ITGB1 | R | CTGCTCCCTTTCTTGTTCTTC | NM_002211 |

| F | ATT ACT CAG ATC CAA CCA C | ||

| ITGB3 | R | TCC TCC TCA TTT CAT TCA TC | NM 000212 |

| F | AAT GCC ACC TGC CTC AAC |

2.6. Silenced integrin β1 subunit

MG63 cells were transduced with shRNA lentiviral transduction particles targeting the integrin beta 1 subunit (ITGB1) (SHCLNV-NM_002211, TRCN0000029645). MG63 cells were plated at 20,000 cells/cm2 and cultured overnight as above. Particles were added to the cells at a multiplicity of infection of 7.5. After an 18 h incubation, transduced cells were selected with full medium containing 0.25 μg/ml puromycin. Silencing was confirmed using real-time qPCR as described below, and β1-silenced MG63 cells (shITGB1-MG63) were confirmed to have 73% less ITGB1 expression than wild type MG63 cells.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data on the chemical composition and contact angle measurements on the titanium disk surface before and after coating with chitosan are presented as averages of the average values on each of the two disks. Data on the amount of chitosan adsorbed on the disks are presented as means ± standard error of the mean of six independent disks per surface. Data on the thickness of the chitosan films are presented in the text as means ± standard deviation (S.D.). Cellular response data in this study are from one of two independent experiments (both with comparable results) with 6 individual cultures per variable in each experiment. Data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all surfaces. When statistical differences were detected, Student's t-test with Bonferroni's modification for multiple comparisons was used. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Surface wettability characterization

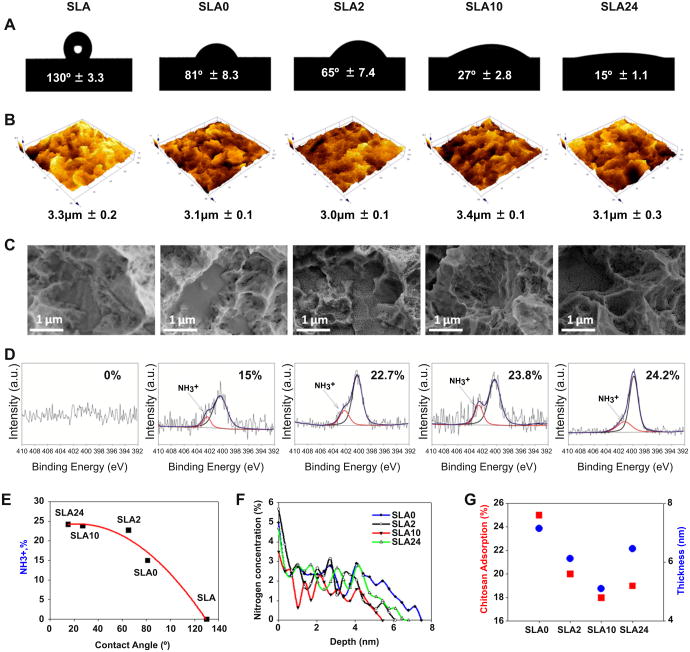

Changes in SLA surface wettability were correlated with the time the surface was aged prior to coating. The contact angle increased on oxygen plasma treated and aged SLA surfaces with increasing aging time (Table 2). The lowest contact angle was found on SLA surfaces immediately after oxygen plasma treatment, while SLA surfaces aged for 24 h exhibited the highest contact angle. After chitosan coating on oxygen plasma treated and aged SLA surfaces this trend in contact angle was shifted (Table 2). SLA24 surfaces showed the lowest contact angle indicated that the most water-wettable surface after coating with chitosan (Fig. 2A). Micron scale surface roughness (Sa, μm) was not modified by chitosan coating (Fig. 2B). The morphology of chitosan thin films formed on SLA surfaces including SLA0, SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 was confirmed by SEM images (Fig. 2C). The surfaces were fully covered with chitosan without adding noticeable micron scale features.

Table 2.

Surface chemical composition (%) of SLA, oxygen plasma treated SLA surfaces, and chitosan nanofilm coated on oxygen plasma treated SLA surfaces was obtained by XPS. Contact angles were measured with ultrapure water, and the amount of adsorbed chitosan on oxygen plasma treated SLA surfaces was calculated by using UV absorbance.

| Chemical composition (%) | Contact angle (degree) | Chitosan adsorptionc μg/disk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Ti2p | O1s | C1s | N1s | Ultrapure water | ||

| SLA | 20.1 | 52.9 | 27.1 | 130 | 0 | |

| SLA/OP/0 ha | 24.3 | 65.9 | 9.8 | 24 | n/a | |

| SLA/OP/2 ha | 23.9 | 63.8 | 12.3 | 35 | n/a | |

| SLA/OP/10 ha | 21.5 | 60.1 | 18.4 | 49 | n/a | |

| SLA/OP/24 ha | 20.6 | 58.8 | 20.6 | 59 | n/a | |

| SLA0b | 10.2 | 52.5 | 32.7 | 4.9 | 81 | 17 ± 1.6 |

| SLA2b | 9.4 | 43.9 | 42.0 | 4.7 | 65 | 14 ± 2.7 |

| SLA10b | 11.4 | 43.8 | 40.8 | 4.1 | 27 | 13 ± 1.4 |

| SLA24b | 12.3 | 47.5 | 35.5 | 4.2 | 15 | 12 ± 3.2 |

For chemical composition and contact angle measurements, data are averages of 2 disks. For chitosan adsorption, data are means ± sem. N = 6 disks/surface.

SLA/OP/h: SLA surfaces were treated with oxygen plasma and aged for the number of hours indicated.

SLAh: SLA surfaces were treated with oxygen plasma and aged for the number of hours indicated followed by coating with chitosan.

70 μg chitosan in 500 μL 0.1 M acetic acid were incubated on the surface for 30 min. UV absorbance at 230 nm was assessed in the starting solution and at the end of the incubation.

Fig. 2.

Surface wettability measured by contact angel (A), roughness determined with confocal laser microscopy (B), surface morphology SEM images (C), and high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of nitrogen (N1s) spectra (D) on surfaces before and after coating chitosan nanofilms on oxygen plasma treated SLA surfaces. The correlation between changing contact angle and charge density variation on SLA surfaces treated with oxygen plasma and then coated with chitosan polyelectrolyte (E). The depth profile of chitosan thin films was characterized by XPS (F). The correlation between chitosan thickness and the amount of adsorbed chitosan on oxygen plasma treated and aged SLA surfaces (G). Red squares represent chitosan adsorption (%) and blue circles represent film thickness. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Primarily titanium (Ti2p), oxygen (O1s), and carbon (C1s) were detected on all surfaces (Table 2). The concentration of O and C was sensitive to oxygen plasma treatment and aging. The detected nitrogen (N1s) peak on chitosan-coated SLA surfaces confirmed the adsorption of chitosan. Positively charged amine groups were quantified by the de-convoluted high resolution of N spectra. Increased positive charge density was obtained on SLA0, SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 surfaces, an effect dependent on aging time (Fig. 2D).

The amount of adsorbed chitosan appeared to vary with the time each surface was aged prior to coating, although differences in adsorption were not statistically significant (Table 2). SLA0 surfaces adsorbed the most chitosan (i.e., the amount remaining in solution was lowest), and adsorption decreased on SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 surfaces. The thickness of chitosan thin films measured by XPS depth profile varied with aging time. The concentration of nitrogen (N1s) in the films varied in a depth-dependent manner, as determined by sputtering Ar+ ions (etching rate 0.017 nm/s) (Fig. 2F). SLA0 (7.14 ± 0.7) surfaces had thicker coatings than SLA2 (6.12 ± 0.3), SLA10 (5.10 ± 0.8), and SLA24 (6.46 ± 0.8) surfaces (Fig. 2F). Film thickness (nm) decreased with decreasing amounts of adsorbed chitosan (Fig. 2G).

3.2. Cellular response of MG63 cells to surface wettability

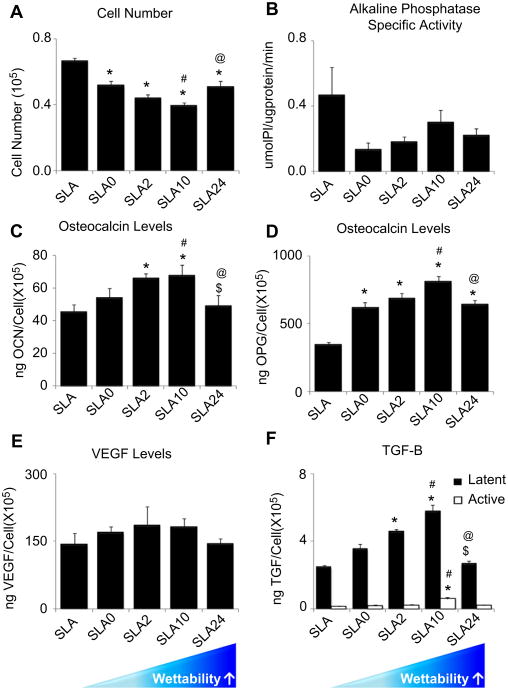

Osteoblast response was sensitive to surface wettability. Cell number decreased on SLA0, SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 surfaces compared to SLA surfaces (Fig. 3A). SLA0, SLA2, and SLA10 had decreased cell numbers in a surface wettability-dependent manner, but the most wettable surface, SLA24, had more cells than SLA10 (Fig. 3A). No differences in alkaline phosphatase specific activity were noted as function of surface wettability (Fig. 3B). Osteocalcin gradually increased on SLA0, SLA2, and SLA10 surfaces compared to SLA surfaces. The highest osteocalcin production by osteoblasts was observed in response to the SLA10 surfaces (Fig. 3C) but there was no difference in osteocalcin on SLA24 surfaces compared to the SLA and SLA0 surfaces and SLA24 surfaces supported lower osteocalcin production than SLA2 and SLA10 surfaces.

Fig. 3.

Effect of the surface wettability on MG63 cell response. MG63 cells were cultured on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) or modified SLA surfaces. Cell number and proteins were determined in all cultures 24 h after confluence on TCPS: cell number (A), alkaline phosphatase specific activity (B), osteocalcin levels (C), osteoprotegerin levels (D), VEGF (E), and TGF-β1 (F) were determined. *, p < 0.05 vs. SLA; #, p < 0.05 vs. SLA0; $, p < 0.05, vs. SLA2; @, p < 0.05, vs. SLA10.

SLA surface wettability had an effect on osteoprotegerin production (Fig. 3D). In comparison to cultures on SLA, cells grown on SLA0, SLA2, SLA10, and SLA24 surfaces produced high levels of this factor, although levels on SLA24 surfaces were lower than on with SLA10 surfaces. VEGF was not affected by different surface wettability (Fig. 3E). Latent TGF-β1 was affected in a similar manner as osteocalcin (Fig. 3F). Increased active TGF-β1 was detected on SLA10 compared to SLA and both latent and active TGF-β1 were lower on SLA24 surfaces.

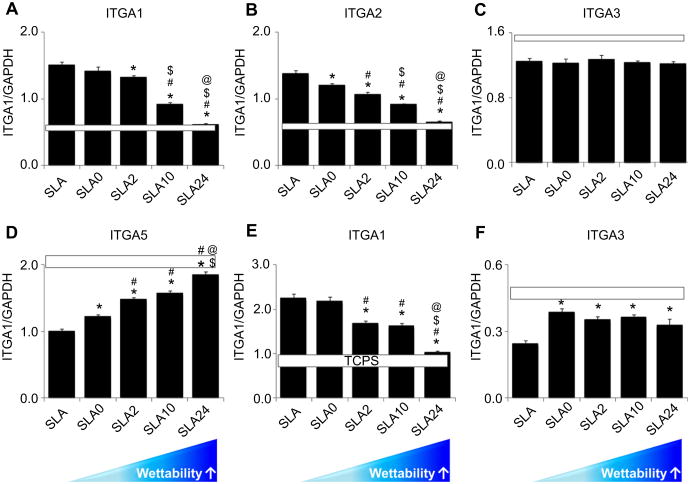

Integrin expression was sensitive to surface wettability. mRNAs for integrin α1 and α2 gradually decreased on modified SLA surfaces in a wettability-dependent manner in comparison with SLA surfaces (Fig. 4A, B). There was no difference between SLA and SLA0 surfaces for integrin α1, but α2 mRNAs were reduced on SLA0 in comparison with SLA. Expression of both integrin subunits on SLA24 was comparable to expression TCPS. α3 expression on all surfaces was comparable to expression on TCPS and was not affected by surface wettability (Fig. 4C). In contrast, mRNAs for α5 were regulated in an opposite manner to α1 and α2 (Fig. 4D). Expression of β1 was comparable to α1 (Fig. 4E). mRNAs for β3 were lower on SLA than on any of the other surfaces and all modified surfaces supported expression of this integrin subunit that was comparable to that seen in cells grown on TCPS (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Effect of surface wettability on integrin subunit mRNA expression in MG63 cells was evaluated in all cultures 12 h after confluence on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS). (A) α1. (B) α2. (C) α3. (D) α5. (E) β1. (F) β3. *, p < 0.05 vs. SLA; #p < 0.05 vs. SLA0; $ p < 0.05 vs. SLA2; @ p < 0.05 vs. SLA10. White long bar indicates TCPS integrin expression levels (mean ± SEM).

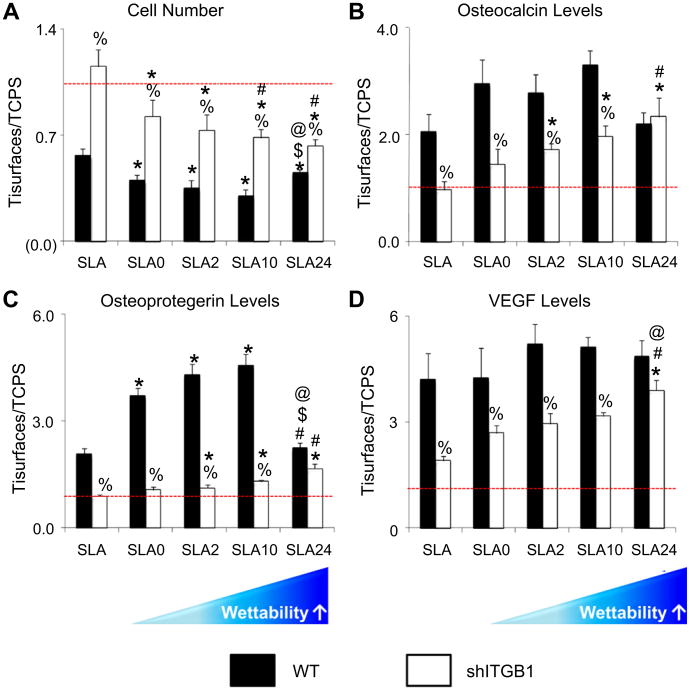

Cells silenced for β1 expression exhibited different responsiveness to the surface wettability gradient than the wild type cells. shITGβ1-MG63 significantly increased in cell number compared with wild type MG63 on all surfaces, although the effect of the wettability gradient was maintained (Fig. 5A). Osteocalcin production by shITGβ1-MG63 cells increase with increasing surface wettability but was significantly lower than by wild type cells on all surfaces except SLA24 (Fig. 5B). Production of OPG (Fig. 5C) and VEGF (Fig. 5D) were also sensitive to β1-silencing.

Fig. 5.

Effect of silencing β1 on response of MG63 cells to surface wettability and microtexture. MG63 and β1-silenced cells were cultured on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) and modified SLA surfaces. Cell number and proteins were determined in all cultures 24 h after confluence on TCPS: cell number (A), alkaline phosphatase specific activity (B), osteocalcin levels (C), osteoprotegerin levels (D), and VEGF (E) were determined. All cellular response results were normalized by TCPS data. %, p < 0.05 vs. WT; *, p < 0.05 vs. SLA; #, p < 0.05, vs. SLA0; $, p < 0.05, vs. SLA2; @, p < 0.05, vs. SLA10.

4. Discussion

Surface wettability plays an important role in the improvement of the early bone healing through protein adsorption, blood clot, cell attachment, and adhesion [10,14]. Many studies support the hypothesis that not only surface wettability but also surface microtexture can impact osteoblast response to a biomaterial [25]. However, the specific roles of individual properties are unclear since all surface properties are connected directly or indirectly. The preparation of surfaces with different wettability under controlled surface chemistry and morphology is a technical challenge [20,26,27]. The contribution of wettability occurs during the initial hot-biomaterial interaction, which happens within a few seconds, making analysis resolution quite limited. To the best of our knowledge, the model described here is the first time the effects of surface roughness, chemistry, and wettability have been decoupled in assessing osteoblast response and integrin expression.

The developed surface modification successfully controlled surface wettability without altering micron scale roughness. Surface preparation consists of three steps: treating SLA surfaces by oxygen plasma followed by aging in atmosphere, and coating the surface with chitosan nanofilms. Oxygen plasma treatment has been widely used to clean, sterilize, and modify surface energy [23,28]. In this study, oxygen plasma was used for impregnating reactive oxygen on SLA surfaces while removing surface carbon contamination. Highly reactive oxygen species created by the oxygen plasma are not stable and easily bind to other molecules, lowering the energy levels [23,28,29]. By aging the surface in atmosphere following removal from the oxygen plasma, different oxygen densities were generated. Thus, freely dangled unstable oxygen on the outermost surface layer either dissipated or bound other molecules from the atmosphere, which was demonstrated by decreasing oxygen with increasing carbon concentration with increasing aging time from 0 to 24 h. Gradually decreased surface wettability was confirmed by contact angle measurement.

After chitosan coating, surface wettability was shifted in an opposite direction. Shifted wettability can be explained by binding to positively charged amine groups in chitosan, and this was confirmed with XPS analysis. In addition, as is typical of linear polysaccharides, chitosan can have a random coil conformation characterized by disordered conformation [30]. Charged chitosan chains can have loop, tail, and train conformations on a surface depending on complex architectures of polymer chain, substrate topography, and the difference in entropy between polymer chains and surfaces [31–34]. The main driving force for chitosan adsorption is electrostatic and an imbalanced force between chitosan and an active surface can induce a number of loops and tails [32,35,36]. Consequently, the adsorbed chitosan chains can have loop or tail confirmations. For SLA0 surfaces characterized as having the highest oxygen density, positively charged chitosan chains can be adsorbed non-specifically followed by increasing anchoring points, and then forming densely packed conformations. Lower oxygen densities on SLA2, SLA10 and SLA24 surfaces can cause charged chitosan chains to be more selectively anchored than on SLA0 surfaces. These factors may contribute differences in surface wettability.

MG63 cell response was sensitive to surface wettability. Cell number decreased while osteocalcin and osteoprotegerin levels increased with increasing surface wettability. Previous studies have shown that osteoblasts are more differentiated on microtextured implant surfaces modified to have excellent wettability than on the same roughness with poor wettability [37]. Interestingly, the MG63 cells were more differentiated and produced more local factors on SLA10 surfaces rather than on the most wettable surface (SLA24). In this study, differences in cellular response can be ascribed to the surface wettability since the micron scale roughness and chemistry were controlled. Because we did not measure charge density, it is not possible to know whether differences in charge density after chitosan coating were responsible for the differences in cellular response.

It is not clear why cell response on the most wettable surface (SLA24) did not mirror the gradient observed on the other surfaces. It is possible that MG63 cells recognize SLA10 surface conditions as an optimum environment for differentiation and thus produce key functional proteins characteristic of mature osteoblasts. Interestingly, cells on the SLA10 surface exhibited a similar pattern in levels of OPG and TGF-β1, supporting our previous studies showing that OPG production is regulated by this growth factor [2].

We previously showed that MG63 cells exhibit an increase in α1, α2 and β1 mRNA when grown on microtextured titanium substrates [16,38]. Moreover, their differentiation on these substrates is mediated by α1β1 and α2β1 signaling [16], whereas α5β1 mediates cell attachment and proliferation [39]. In the present study, we found that integrin expression is sensitive to surface wettability on rough surfaces, with expression of α1, α2, and β1 decreasing and α5 increasing as the microtextured surfaces became more wettable. For all three integrin subunits, mRNA levels were comparable to those seen on TCPS when the cells were grown on the SLA24 surface. This was an unexpected finding and suggests that wettability alone was not the controlling factor. When MG63 cells are cultured on SLA surfaces modified to have high surface energy by retaining them in a hydrated state after oxygen plasma treatment, α2β1 and α1β1 are increased but α5 is decreased [39]. Thus, the chitosan chemistry may play an important role in determining which proteins are adsorbed on the surface and subsequently which integrins are expressed. As we found previously using antibodies to block α5β1 signaling in MG63 cells [39], higher expression of α5 on SLA24 is associated with higher cell number and lower differentiation markers than seen in MG63 cells on the other surfaces where α2 expression is increased [16], supporting the hypothesis that these integrins mediate different cell processes.

Both α2 and α5 partner with β1 in the cell to initiate integrin signaling. Previous studies in our lab indicated that surface microtexture was the important property regulating β1 expression and osteoblast differentiation mediated by β1 integrin signaling [38]. Silencing β1 resulted in increased cell numbers as well as in reductions in osteocalcin, osteoprotegerin, and VEGF. This study supports that surface roughness effect was inhibited when β1 was silenced. Interestingly, β1-silenced MG63 cells showed that surface wettability also plays an important role to modulate osteoblast differentiation and local factor production and suggests that integrins other than α1β1 and α2β1 may be involved.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown that a surface wettability gradient was successfully developed with identical chemistry without altering microstructure of SLA surfaces. Osteoblast differentiation is regulated in a wettability-dependent manner, in which cell number is decreased and osteocalcin and osteoprotegerin are increased on SLA0, SLA2, and SLA10 surfaces. However, the most water-wettable surface, SLA24, contributes to cell response in a different way compared to less water-wettable surfaces. Integrin expression directly depends on wettability. Overall, surface wettability as a primary regulator enhanced osteoblast differentiation, but integrin expression depends on both surface microstructure and surface chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an USPHS Grant AR052102 and the ITI Foundation. The PT and SLA disks were provided by Institut Straumann AG.

References

- 1.Olivares-Navarrete R, Hyzy SL, Hutton DL, Erdman CP, Wieland M, Boyan BD, et al. Direct and indirect effects of microstructured titanium substrates on the induction of mesenchymal stem cell differentiation towards the osteoblast lineage. Biomaterials. 2010;31(10):2728–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz Z, Olivares-Navarrete R, Wieland M, Cochran DL, Boyan BD. Mechanisms regulating increased production of osteoprotegerin by osteoblasts cultured on microstructured titanium surfaces. Biomaterials. 2009;30(20):3390–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gittens RA, McLachlan T, Olivares-Navarrete R, Cai Y, Berner S, Tannenbaum R, et al. The effects of combined micron-/submicron-scale surface roughness and nanoscale features on cell proliferation and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2011;32(13):3395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JH, Olivares-Navarrete R, Wasilewski CE, Boyan BD, Tannenbaum R, Schwartz Z. Use of polyelectrolyte thin films to modulate osteoblast response to microstructured titanium surfaces. Biomaterials. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.074. Epub: 4/26/2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lossdorfer S, Schwartz Z, Wang L, Lohmann CH, Turner JD, Wieland M, et al. Microrough implant surface topographies increase osteogenesis by reducing osteoclast formation and activity. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70A(3):361–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavenus S, Pilet P, Guicheux J, Weiss P, Louarn G, Layrolle P. Behaviour of mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts and osteoblasts on smooth surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2011;7(4):1525–34. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster TJ, Ergun C, Doremus RH, Bizios R. Hydroxylapatite with substituted magnesium, zinc, cadmium, and yttrium. II. Mechanisms of osteoblast adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59(2):312–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulgar-Tulloch AJ, Bizios R, Siegel RW. Human mesenchymal stem cell adhesion and proliferation in response to ceramic chemistry and nanoscale topography. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;90A(2):586–94. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uedayukoshi T, Matsuda T. Cellular-responses on a wettability gradient surface with continuous variations in surface compositions of carbonate and hydroxyl-groups. Langmuir. 1995;11(10):4135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogler EA. Structure and reactivity of water at biomaterial surfaces. Adv Colloid Interface. 1998;74:69–117. doi: 10.1016/s0001-8686(97)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vieira EP, Rocha S, Pereira MC, Moehwald H, Coelho MAN. Adsorption and diffusion of plasma proteins on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces: effect of trifluoroethanol on protein structure. Langmuir. 2009;25(17):9879–86. doi: 10.1021/la9009948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raines AL, Olivares-Navarrete R, Wieland M, Cochran DL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Regulation of angiogenesis during osseointegration by titanium surface microstructure and energy. Biomaterials. 2010;31(18):4909–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rupp F, Scheideler L, Olshanska N, de Wild M, Wieland M, Geis-Gerstorfer J. Enhancing surface free energy and hydrophilicity through chemical modification of microstructured titanium implant surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;76A(2):323–34. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz F, Wieland M, Schwartz Z, Zhao G, Rupp F, Geis-Gerstorfer J, et al. Potential of chemically modified hydrophilic surface characteristics to support tissue integration of titanium dental implants. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;88B(2):544–57. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Underlying mechanisms at the bone-biomaterial interface. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56(3):340–7. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivares-Navarrete R, Raz P, Zhao G, Chen J, Wieland M, Cochran DL, et al. Integrin alpha 2 beta 1 plays a critical role in osteoblast response to micronscale surface structure and surface energy of titanium substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(41):15767–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805420105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ballester-Beltran J, Rico P, Moratal D, Song W, Mano JF, Salmeron-Sanchez M. Role of superhydrophobicity in the biological activity of fibronectin at the cell-material interface. Soft Matter. 2011;7(22):10803–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siebers MC, ter Brugge PJ, Walboomers XF, Jansen JA. Integrins as linker proteins between osteoblasts and bone replacing materials. A critical review Biomaterials. 2005;26(2):137–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berman AE, Kozova NI, Morozevich GE. Integrins: structure and signaling. Biochem-Moscow. 2003;68(12):1284–99. doi: 10.1023/b:biry.0000011649.03634.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JH, Schwartz Z, Olivares-Navarrete R, Boyan BD, Tannenbaum R. Enhancement of surface wettability via the modification of microtextured titanium implant surfaces with polyelectrolytes. Langmuir. 2011;27(10):5976–85. doi: 10.1021/la2000415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genzer J, Bhat RR. Surface-bound soft matter gradients. Langmuir. 2008;24(6):2294–317. doi: 10.1021/la7033164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 1998;93(2):165–76. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JH, Olivares-Navarrete R, Baier RE, Meyer AE, Tannenbaum R, Boyan BD, et al. Effect of cleaning and sterilization on titanium implant surface properties and cellular response. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(5):1966–75. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyan BD, Batzer R, Kieswetter K, Liu Y, Cochran DL, Szmuckler-Moncler S, et al. Titanium surface roughness alters responsiveness of MG63 osteoblast-like cells to 1α,25-(OH)2D3. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39(1):77–85. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199801)39:1<77::aid-jbm10>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altankov G, Grinnell F, Groth T. Studies on the biocompatibility of materials: fibroblast reorganization of substratum-bound fibronectin on surfaces varying in wettability. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;30(3):385–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199603)30:3<385::AID-JBM13>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miranda Coelho N, Gonzalez-Garcia C, Salmeron-Sanchez M, Altankov G. Arrangement of type IV collagen on NH(2) and COOH functionalized surfaces. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108(12):3009–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.23265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arifvianto B, Suyitno, Mahardika M, Dewo P, Iswanto PT, Salim UA. Effect of surface mechanical attrition treatment (SMAT) on microhardness, surface roughness and wettability of AISI 316L. Mater Chem Phys. 2011;125(3):418–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene G, Yao G, Tannenbaum R. Wetting characteristics of plasma-modified porous polyethylene. Langmuir. 2003;19(14):5869–74. doi: 10.1021/la026940+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene G, Tannenbaum R. Adsorbtion of polyelectrolyte multilayers on plasma-modified porous polyethylene. Appl Surf Sci. 2004;238(1–4):101–7. doi: 10.1021/la036048i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris ER, Rees DA, Thom D, Welsh EJ. Conformation and intermolecular interactions of carbohydrate chains. J Supramol Struct Cell. 1977;6(2):259–74. doi: 10.1002/jss.400060211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hershkovits E, Tannenbaum A, Tannenbaum R. Polymer adsorption on curved surfaces: a geometric approach. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111(33):12369–75. doi: 10.1021/jp0725073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Shaughnessy B, Vavylonis D. Non-equilibrium in adsorbed polymer layers. J Phys-Condens Matter. 2005;17(2):R63–99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granick S, Kumar SK, Amis EJ, Antonietti M, Balazs AC, Chakraborty AK, et al. Macromolecules at surfaces: research challenges and opportunities from tribology to biology. J Polym Sci B. 2003;41(22):2755–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleer GJ, Scheutjens J. Interaction between adsorbed layers of macromolecules. J Colloid Interface. 1986;111(2):504–15. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyklema J, Deschenes L. The first step in layer-by-layer deposition: electrostatics and/or non-electrostatics? Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;168(1–2):135–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panja D, Barkema GT, Kolomeisky AB. Non-equilibrium dynamics of single polymer adsorption to solid surfaces. J Phys-Condens Matter. 2009;21(24) doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/21/24/242101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao G, Raines AL, Wieland M, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD. Requirement for both micron- and submicron scale structure for synergistic responses of osteoblasts to substrate surface energy and topography. Biomaterials. 2007;28(18):2821–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang LP, Zhao G, Olivares-Navarrete R, Bell BF, Wieland M, Cochran DL, et al. Integrin beta(1) silencing in osteoblasts alters substrate-dependent responses to 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D-3. Biomaterials. 2006;27(20):3716–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keselowsky BG, Wang L, Schwartz Z, Garcia AJ, Boyan BD. Integrin alpha(5) controls osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation responses to titanium substrates presenting different roughness characteristics in a roughness independent manner. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80A(3):700–10. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]