Abstract

Background

Despite its benefit for treating active tuberculosis, directly observed therapy (DOT) for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) has been largely understudied among challenging inner city populations.

Methods

Utilizing questionnaire data from a comprehensive mobile healthcare clinic in New Haven, CT from 2003 to July 2011, a total of 2523 completed tuberculin skin tests (TST’s) resulted in 357 new LTBIs. Multivariate logistic regression correlated covariates of the two outcomes 1) initiation of isoniazid preventative therapy (IPT) and 2) completion of 9-months IPT.

Results

Of 357 new LTBIs, 86.3% (n=308) completed screening CXRs: 90.3% (n=278) were normal and 0.3% (n=1) with active tuberculosis. Of those completing CXR screening, 44.0% (n=135) agreed to IPT: 69.6% (n=94) selected DOT, and 30.4% (n=41) selected SAT. Initiating IPT was correlated with undocumented status (AOR=3.43; p<0.001) and being born in a country of highest and third highest tuberculosis prevalence (AOR=14.09; p=0.017 and AOR=2.25; p=0.005, respectively). Those selecting DOT were more likely to be Hispanic (83.0% vs 53.7%; p<0.0001), undocumented (57.4% vs 41.5%; p=0.012), have stable housing (p=0.002), employed (p<0.0001), uninsured (p=0.014), no prior cocaine or crack use (p=0.013) and no recent incarceration (p=0.001). Completing 9-months of IPT was correlated with no recent incarceration (AOR 5.95; p=0.036) and younger age (AOR 1.03; p=0.031). SAT and DOT participants did not significantly differ for IPT duration (6.54 vs 5.68 months; p=0.216) nor 9-month completion (59.8% vs 46.3%; p=0.155).

Conclusions

In an urban mobile healthcare sample, screening completion for LTBI was high with nearly half initiating IPT. Undocumented, Hispanic immigrants from high prevalence tuberculosis countries were more likely to self-select DOT at the mobile outreach clinic, potentially because of more culturally, linguistically, and logistically accessible services and self-selection optimization phenomena (SSOP). Within a diverse, urban environment, DOT and SAT IPT models for LTBI treatment resulted in similar outcomes, yet outcomes were hampered by differential measurement bias between DOT and SAT participants.

Keywords: Latent Tuberculosis, Immigrant, Foreign-Born, Directly Observed Therapy, Self-Administered Therapy, Mobile Health Care

BACKGROUND

Despite active tuberculosis (TB) being highly prevalent and contributing to high morbidity and mortality worldwide,[1] the US remains a low-burden country.[2] Since 2001, TB incidence among foreign-born exceeded US-born persons in the US[2] Despite this low TB incidence, identification and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) remains the cornerstone of TB elimination yet continues to be a public health challenge due to being an asymptomatic, mainly non-reportable disease, and adherence challenges to a 9-month course of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT).

Despite the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendation to treat LTBI using 9 months of IPT,[3] numerous challenges remain, including convincing patients with an asymptomatic disease to accept treatment, regimen non-adherence or default, concerns about adverse side effects, and the inability to enforce treatment for a non-communicable infection that may remain latent lifelong.[3] Though directly observed therapy (DOT) is the standard of care for treating active TB, adherence to treatment and completion rates for LTBI remain low, particularly for medically and socially vulnerable patient populations and for newly arrived immigrants.[4],[5] With a 10% lifetime reactivation risk of progression to active TB, and with most active TB cases occurring in foreign-born populations within five years after arrival to the US,[6] it is imperative to maintain effective LTBI testing and treatment strategies.

In addition to treatment of active TB, DOT has been effectively used in the treatment of other diseases, including HIV[7-9] and HCV.[10] Despite its benefit for treating active TB, directly observed therapy (DOT) for LTBI has been largely understudied among challenging inner city populations. To determine the extent to which patients screened positive for TB using tuberculin skin testing (TST), we examined clinical data on active TB screening, followed by the acceptance of IPT for the treatment of those with LTBI. Among those with LTBI, we examined LTBI treatment outcomes for patients opting to receive medications as DOT or self-administered therapy (SAT) for a disease that is clinically silent and may never result in active disease within a mobile healthcare clinic that provided free comprehensive services in an urban setting.

METHODS

Setting

New Haven, Connecticut, the seventh poorest US city for its size with approximately 130,000 persons with a median income of $39,920[11] has exceedingly high rates of poverty, unemployment, and problems with substance abuse and HIV/AIDS. The Community Health Care Van (CHCV), a free, mobile healthcare clinic operating since 1993 provides a number of free clinical services, including healthcare, screening for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections,[12] screening and vaccination for preventable infections,[13] buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence,[14-17] tuberculosis screening,[18] syringe and condom distribution, directly administered antiretroviral therapy (DAART),[7,19-21] and a variety of case management[22] and post-prison release services.[23] In 2003, the CHCV began a routine TB screening program and offered DOT to support New Haven’s undocumented and underserved community. Dedicated medical, case management and counseling staff are bilingual and bicultural in Spanish and provide weekday services in four distinct impoverished neighborhoods within New Haven, CT.

Clinical Procedures

All CHCV patients undergo a standardized baseline clinical encounter questionnaire, and the data are maintained in an electronic medical record. TST positivity is defined using standard criteria: induration ≥10mm for HIV negative and ≥5mm for HIV-positive individuals. All TST+ clients undergo an additional brief symptom assessment (cough/dyspnea, fever/night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, and hemoptysis) recommended by the WHO[24] and are referred for chest radiograph (CXR). For TST+ clients without evidence for active tuberculosis or hepatic transaminase levels greater than five times the upper limits of normal, they are offered 9 months of IPT as: 1) DOT, where IPT is observed twice-weekly (900 mg) along with vitamin B6 (100mg); or 2) SAT, with referral to a free, hospital-based TB specialty clinic that provides outpatient IPT with 90 day allotments of daily prescribed isoniazid and B6. DOT provides twice-weekly observed doses while SAT does not monitor adherence to therapy. Hepatic transaminases are monitored at baseline and again between 4-6 weeks at no cost at both sites. No monetary incentives were given either for testing or treatment, and a certificate was provided to each client upon completion of the DOT program. Monthly progress and completion reports were provided to the Connecticut Department of Public Health. This study was reviewed and approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

Two clinically relevant dependent variables were selected, including correlates of: 1) initiating IPT; and 2) completing IPT with stratified analysis for those selecting DOT or SAT. Independent variables were chosen on the clinical relevance to LTBI. Stable housing was defined as living in one’s own apartment, one’s own house, or with one’s family. Unstable housing was defined as living in a shelter, halfway house, hotel, or a public place. Committed relationship was defined as being married or living together. Non-committed relationship was defined as being divorced, separated, widowed, or single. Foreign-born was defined by being born outside of the US or Puerto Rico. Recent incarceration and recent emergency room visits were defined within six months of completing the questionnaire. Interpersonal violence was defined by self-reported history of domestic violence, sexual assault, or both. Cocaine use was inclusive of all forms: powdered, smoked (crack cocaine), or injected either singly or in combination with heroin. “Speedball” is known as an injected mixture of cocaine and heroin. Hazardous alcohol use was defined as more than two drinks daily for men and more than one drink daily for women. Sex solicitation was defined as ever having paid money for sexual intercourse. Exchange for sex was defined as ever having exchanged sex for money, drugs, or protection. Countries of origin among the foreign-born were organized into five categories of tuberculosis prevalence based on first (least prevalent) to fifth (most prevalent) as defined by the WHO.[25,26]

Fisher’s Exact Test and the chi-square distribution were used to discern differences between the two groups according to sample size for categorical variables. The t-test was used to compare averages of continuous variables (age, months of therapy completed) between the two groups. Total months DOT therapy were recorded in the central database and confirmed with hand-tallied medical records from the CHCV. Total months of SAT therapy were confirmed with electronic TB clinic records; for those not completing therapy, a midpoint calculation of 1.5 months was set from the last date of prescription for the 90-day medication supply.

As a safeguard against measurement error, each medical record from all New Haven hospitals and affiliated clinic systems were reviewed to confirm chest-x-ray date, results, and doses received. After provision of release of medical information by patients, the Yale IRB approved a search of medical records. Date of birth was used to confirm patient identify for those with name changes or name discrepancies. The two dependent variables of initiation of IPT and completion of either SAT or DOT therapy at nine months were observed completely, and the covariates relating to predisposing factors were missing at a varying percentage (0-10%). Using a set of two dependent variables (i.e. initiation of IPT; completion of 9 months of IPT) and multiple imputations using standardized approaches of covariates,[3] we conducted several logistic regressions. The covariates that were found to be significant at p<0.05 level in the bivariate models were entered into a multivariate logistic model for initiation of IPT. Regression referents are the complement of dichotomous variables, unless otherwise specified for race/ethnicity and WHO category. WHO category was defined from least prevalent (WHO category 1) to most prevalent (WHO category 5) from WHO Stop TB country specific calculations.[26]

Covariates significant at the p<0.20 level were entered into the multivariate logistic model for completion of nine months of therapy.

Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) as well as Pearson’s Chi-squared test were used to assess the relative goodness-of-fit and to discriminate among various multivariate models. The best model fit contained the lowest AIC with Pearson’s Chi-square test indicating no better model existed (p-value >0.05). All analyses were carried out using intention to treat analysis using STATA 12.1 IC.[27]

RESULTS

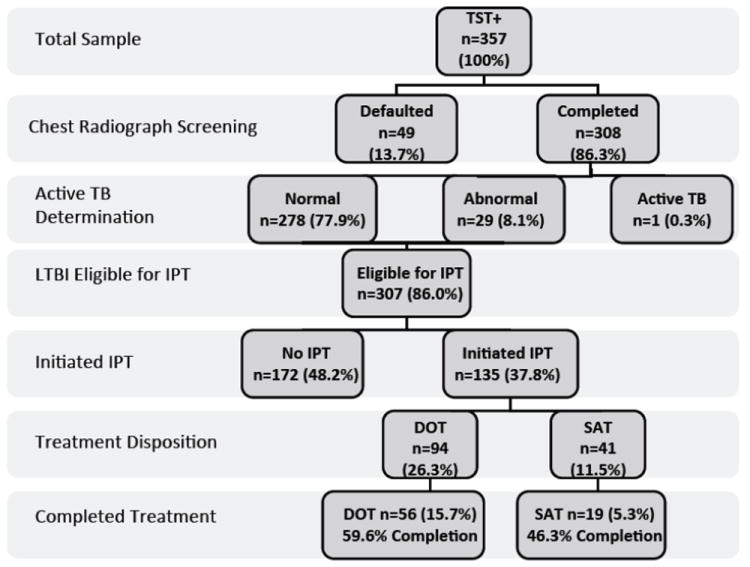

From 2003 to July 2011, a total of 3158 TSTs were placed with 2523 TSTs read (representing 1325 unique, eligible individuals) resulting in 357 newly positive TST’s. Of the 357 TST-positive patients, 308 (86.3%) completed recommended screening CXR: 278 (90.3%) were normal, 29 (9.4%) had a nodule, and 1 had active tuberculosis (Figure 1). Of the 135 initiators of isoniazid preventative therapy (IPT), 69.6% (n=94) initiated DOT, and 30.4% (n=41) initiated SAT, representing an average 44.0% initiation overall. Isoniazid completion rates at 9 months were 59.6% for DOT (n=56) and 46.3% for SAT (n=19). For those completing 6 months of IPT, 70.0% (n=62) of the DOT group and 61.0% (n=25) of the SAT group were successful. Symptom inventory among those newly positive TST individuals receiving DOT revealed that 57.14% reported loss of appetite, 50.8% had prior BCG vaccination, 23.0% had known prior contact with tuberculosis, 11.6% reported cough, 11.4% reported weight loss, and 11.1% reported sweats. No patients reported hemoptysis. Mexico was the most prevalent country of origin (n=32; 23.7%) for those initiating IPT followed by Ecuador (n=27; 20.0%), USA/Puerto Rico (n=23; 17.0%), Guatemala (n=7; 5.2%), with <3% each from Peru, Ghana, Colombia, and the Dominican Republic.

Figure 1.

Latent tuberculosis screening and treatment allocation algorithm (n=357). The one case of active tuberculosis completed the four drug regimen.

The self-selected DOT group statistically differed from the SAT group by self-identifying as being Hispanic (83.0% vs 53.7%; p=0.001), undocumented (57.4% vs 41.5%; p=0.012), older age (41.2 vs 36.4 years; p=0.039), having stable housing (59.6% vs 39.0%; p=0.002), being employed (p<0.0001), being uninsured (p=0.014), having no prior cocaine use (p=0.013), and not having been recently incarcerated (p=0.001). The SAT group was more likely to be of African descent (p=0.012), to have health insurance (p=0.014), to have had recent incarceration (p=0.001), and to have ever used any form of cocaine (p=0.013). The groups were similar with respect to educational level, recent drug use in the past 30 days, recent emergency room utilization, and baseline HIV (9.6%) or Hepatitis C (0 to 4.3%) infection. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients starting isoniazid preventative therapy (IPT) stratified by method of treatment delivery (n=135).

| Total n=135 | DOT n=94 | SAT n=41 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age (mean years) | 39.8 | 41.2 | 36.4 | 0.039 |

| Treatment duration (mean months) | 6.28 | 6.54 | 5.68 | 0.216 |

| Completion of 9-month IPT | 75 (55.6) | 56 (59.8) | 19 (46.3) | 0.155 |

| Male gender | 84 (62.2) | 58 (61.7) | 26 (63.4) | 0.850 |

| Race/ethnicity: | ||||

| White | 6 (4.4) | 2 (2.1) | 4 (9.8) | 0.023 |

| Black | 27 (20.0) | 12 (12.8) | 15 (36.6) | 0.012 |

| Asian/Other | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.176 |

| Hispanic | 100 (74.1) | 78 (83.0) | 22 (53.7) | <0.0001 |

| Foreign-born | 106 (78.5) | 79 (84.0) | 27 (65.9) | 0.147 |

| Undocumented immigrant | 71 (52.6) | 54 (57.4) | 17 (41.5) | 0.012 |

| Number people in house (average) | 6.68 | 4.28 | 13.14 | 0.047 |

| Completed high school | 65 (48.1) | 43 (45.7) | 22 (53.7) | 0.898 |

| Stable housing | 72 (53.3) | 56 (59.6) | 16 (39.0) | 0.002 |

| Committed relationship | 54 (40.0) | 41 (43.6) | 13 (31.7) | 0.057 |

| Employed | 85 (63.0) | 73 (77.7) | 12 (29.3) | <0.0001 |

| Health insurance | 24 (17.8) | 11 (11.7) | 13 (31.7) | 0.014 |

| Injection drug use history | 4 (3.0) | 2 (2.1) | 2 (4.9) | 0.585 |

| Drug use last 30 days: | ||||

| Any injected drug | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Heroin | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (2.4) | 1.000 |

| Speedball | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | n/a |

| Cocaine | 5 (3.7) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (4.9) | 0.639 |

| Marijuana | 6 (4.4) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (7.3) | 0.368 |

| Drug use ever: | ||||

| Heroin | 10 (7.4) | 6 (6.4) | 4 (9.8) | 0.491 |

| Speedball | 6 (4.4) | 3 (3.2) | 3 (7.3) | 0.368 |

| Cocaine | 23 (17.0) | 11 (11.7) | 12 (8.9) | 0.013 |

| Marijuana | 40 (29.6) | 24 (25.5) | 16 (39.0) | 0.151 |

| Hazardous alcohol use | 67 (49.6) | 48 (51.1) | 19 (46.3) | 0.614 |

| Transactional sex: | ||||

| Sex solicitation | 21 (15.6) | 14 (14.9) | 7 (17.1) | 0.748 |

| Exchange for sex | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.9) | 0.091 |

| Interpersonal violence victim | 8 (5.9) | 4 (4.3) | 4 (9.8) | 0.245 |

| Sexually transmitted infection | 24 (17.8) | 14 (14.9) | 10 (24.4) | 0.222 |

| Mental health diagnosis | 19 (14.1) | 11 (11.7) | 8 (19.5) | 0.283 |

| HIV monoinfection | 13 (9.6) | 9 (9.6) | 4 (9.8) | 1.000 |

| Hepatitis C monoinfection | 4 (3.0) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.314 |

| Incarceration recent | 10 (7.4) | 2 (2.1) | 8 (19.5) | 0.001 |

| Emergency room recent | 19 (14.1) | 11 (11.7) | 8 (19.5) | 0.238 |

DOT: directly observed therapy; SAT: self-administered therapy; Speedball: injected mixture of cocaine and heroin; IPT: isoniazid preventive therapy

Of the 357 individuals with a newly diagnosed TST+, those choosing IPT (n=135) compared to those who declined IPT (n=172) were statistically more likely to be of Asian descent (p<0.0001), foreign-born (p<0.0001), undocumented (p<0.0001), and have a high school education (p=0.021). Those declining IPT reported recent incarceration (p=0.022), recent emergency room visitation (p=0.029), had previously injected drugs (p=0.001), and previously used cocaine (p=0.001) or marijuana (p<0.0001) (Table Not Shown).

IPT initiation was correlated in final multivariate models with undocumented status (AOR=3.43; p<0.001) and being born in a country of highest and third highest tuberculosis prevalence (AOR=14.09; p=0.017 and AOR=2.25; p=0.005, respectively). (Table 4)

Table 4.

Best-Fit Models with Correlates of Accepting (Initiating) and Completing Isoniazid Preventive Therapy.

| Isoniazid Preventive Therapy

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiating (Accepting) | Completing 9 Months | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | p-value | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| WHO category 5 | 14.09 | 1.60,123.71 | 0.017 | Younger age | 1.03 | 1.003,1.06 | 0.031 |

| Undocumented immigrant | 3.43 | 2.08,5.65 | <0.001 | No recent Incarceration | 5.95 | 1.12,31.62 | 0.036 |

| WHO category 3 | 2.25 | 1.28,3.96 | 0.005 | Speedball* ever injected | 11.07 | 0.89,138.07 | 0.062 |

| Hazardous alcohol use | 0.58 | 0.28,1.18 | 0.134 | ||||

|

|

|||||||

| AIC | 425.29 | 181.93 | |||||

| Pearson X2 p-value | 0.86 | 0.36 | |||||

WHO: World Health Organization; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; AIC: Akaike Information Criteria

Speedball: injected mixture of heroin and cocaine

Completing the full 9 months of IPT correlated in final multivariate models with not having being incarcerated within six months of diagnosis (AOR 5.95; p=0.036) and younger age (AOR 1.03; p=0.031). (Table 4)

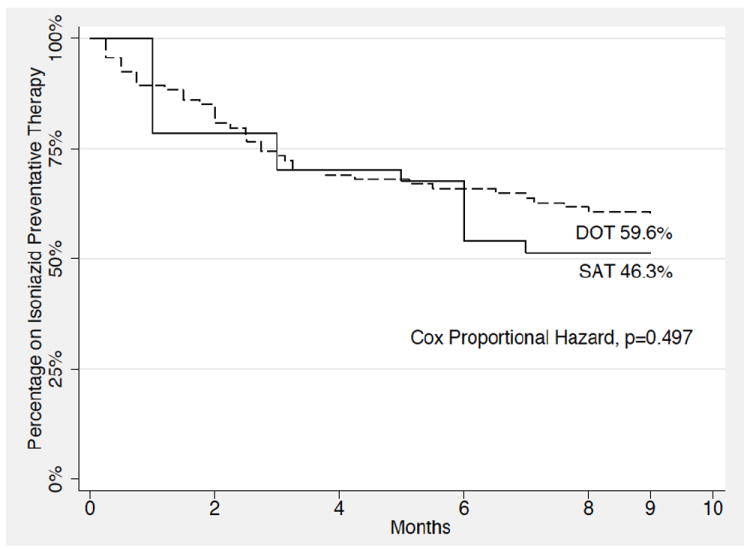

Attrition from LTBI treatment is presented as Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 2). Though usually reserved for variable time to event analysis, this format is helpful to visualize the relatively high percentage of adherence to completion as well as to compare the DOT and SAT groups visually, though ultimately found to be nonsignificant using the Cox Proportional Hazard testing (p=0.497).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of months completion of isoniazid preventative therapy illustrating directly observed therapy (DOT) vs self-administered therapy (SAT) (n=135).

DISCUSSION

The is the first study to our knowledge that successfully documents directly observed therapy (DOT) for latent tuberculosis infection (LBTI) in a multicultural, predominately foreign-born, urban, poor population with completion rates above national averages despite low levels of education and history of drug use.[28] The average treatment IPT duration was not significantly higher in the DOT group (p<0.216), and the total 9-month IPT completion of the DOT group did not statistically differ from the SAT group (p=0.155).

As the CHCV staff was bilingual with several having a Hispanic background, there was an important cultural trust that was established on the CHCV for foreign-born clients. This successful cultural and social affinity within the DOT group was reflected in the significant difference of being of Hispanic origin and foreign-born among those selecting DOT. Further, CHCV staff promoted bilingual education for each client on tuberculosis transmission, importance of therapy adherence, and the risk of reactivation tuberculosis without therapy and created a weekly social support network for those completing DOT.

Our intention-to-treat analysis included all clients in both the DOT and SAT groups who initiated nine months of therapy for the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. By this method of combining all individuals who initiated therapy in both treatment arms for analysis, bias between the two treatment locations was reduced. As evidence suggests that 6 months of IPT is adequate for HIV negative LTBI, an exceptionally high completion rate for 6 months was reached at 70.0% (n=66) for the DOT group and 61.0% (n=25) for the SAT group, respectively, though not found to be statistically different. Though these findings did not show any statistical differences, measurement bias was likely introduced by the differential methods by which retention on treatment and completion was measured. For example in the DOT, all doses were measured and an exact date of discontinuation could be determined. For the SAT group, however, besides electronic clinical notes documenting patient report of taking IPT, no objective measurement of adherence was recorded except pharmacy prescription records documenting increments of 90-day allotments. One had to therefore make assumptions not only in adherence, but also in the date of completion by choosing a mid-point date between the 3-month prescription dispensations.

Another limitation of the study includes selection bias as patients were not randomized to either the DOT or SAT treatment groups and instead freely chose 1) whether to initiate therapy at all and 2) by differential approach to providing medications. Patients could have self-selected the treatment approach based on location, convenience, and possible cultural affinity to either clinic. On one hand, patients may have perceived that they were getting more “specialized” care if treated in a specialty TB clinic, whereas others might have preferred the casual and user-friendly atmosphere provided on the mobile health clinic, where they had been previously screened. As SAT was not also offered within the mobile clinic setting, it is difficult to separate a cultural affinity preference of twice weekly DOT on the CHCV from an every three-month SAT preference at the specialized TB clinic. The IPT completion rate parity between DOT and SAT groups may reflect patients optimizing their own choices for successful treatment.

Such treatment arm equivalence may be explained by what we describe as the self-selection optimization phenomenon (SSOP) in which demographic groups will self-sort according to cultural/linguistic affinity and logistic/financial convenience that they perceive would optimize their own self-interest for successful health outcomes. We observe that a mainly uninsured, undocumented Hispanic demographic would gravitate towards a free, bilingual clinic that is sensitive to preserving undocumented status in a confidential manner. Similarly, those patients who are primarily English-speaking, indoctrinated with the notion that care should be specialized, may perceive themselves to have great self-efficacy and preferring medication prescription every three months, and not needing a high degree of anonymity, resulting in self-selecting the traditional TB specialty clinic to optimize their own health outcome. Having both clinic options is shown to be valuable models for IPT care with diverse demographics within this urban setting. Irrespective of how patients self-selected, when given the option, treatment outcomes were excellent.

Of the 357 new cases, 67.2% (n=240) did not have health insurance, 58.3% (n=208) were foreign-born, and 35.6% (n=127) were undocumented. The large percentage of foreign-born individuals in this study is testament of the importance of continuing community outreach work to reach those clients at the highest risk for reactivation tuberculosis who may not seek care in traditional care settings and who largely do not have health insurance.

Though only one active case of tuberculosis was found, this individual was traced to a large family of more than ten close contacts who subsequently underwent timely evaluation and prophylaxis by the public health department and thus potentially averted many other active cases in the Hispanic community. This mobile clinic outreach program collectively tested and facilitated care for 91 persons at 6 months and 75 persons at 9 months without financial or other reward incentives[29] and thus played a key public health prevention and potentially cost-saving role in averting many potential active tuberculosis cases.

Those more likely both to initiate IPT and to complete the 9-month IPT course had no recent incarceration, underscoring that reducing or eliminating the need for incarceration though alternative sentencing or enhanced community-based mental health and substance use interventions may serve to decrease disruption in urban community-based health initiatives. Alternatively, there might have been a detection bias against inclusion of this demographic because of the routine TB screening procedures deployed in prisons and jails in Connecticut.

The finding that the majority of patients completed at 6 months of IPT has important implications from new approaches to IPT. Recently, CDC has recommended a three-month “weekly” treatment strategy with rifapentine and isoniazid, potentially providing even greater opportunity to improve medication compliance and completion rates for LBTI.[30] Culturally appropriate TST screening among immigrant, undocumented, and other high-risk groups, however, continues to be a vital cornerstone to avert future infections, and despite structured public health efforts, community outreach remains central to future TB prevention efforts.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates clinical outcome parity of directly observed therapy (DOT) compared to self-administered therapy (SAT) both at six and nine months for isoniazid prevention therapy (IPT) for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). DOT within a mobile clinic model is a feasible alternative for especially high-risk populations who may otherwise avoid traditional sites for healthcare (e.g., foreign-born, undocumented, and uninsured populations). Moreover, it results in similar outcomes as traditional TB clinic approaches that do not include such marginalized populations who appear to prefer integrated services with culturally and linguistically appropriate educational support. The reason for high percentage completion rates within both DOT and SAT treatment groups may partially be ascribed to the self-selection optimization phenomenon (SSOP) in which demographic groups gravitate towards the clinic model that is perceived to maximize their own health outcomes.

This study provides empirical evidence that a culturally and geographically accessible mobile healthcare clinic like the CHCV is an integral factor for the high percentage of screening and completion for LBTI and would serve as successful future models of LBTI. Such clinical strategies that contain either a DOT or SAT regimen for treating LTBI, especially the newer 12-week strategies, is promising for higher screening, adherence, and completion rates in foreign-born and undocumented urban populations with or at risk for LTBI.

Table 2.

Initiation of isoniazid preventive therapy by bivariate and multiple logistic regression correlates (n=357).

| Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Crude OR | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 | 0.98-1.02 | 0.940 | |||

| Male gender | 0.87 | 0.56,1.36 | 0.555 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity: | ||||||

| White | referent | |||||

| Black | 1.62 | 0.60,4.32 | 0.340 | |||

| Asian | 9.33 | 0.72,120.41 | 0.087 | |||

| Hispanic | 4.06 | 1.61,10.20 | 0.003 | 1.36 | 0.67,2.76 | 0.401 |

| Foreign-born: | 4.36 | 2.61,7.30 | 0.001 | 1.23 | 0.46,3.28 | 0.676 |

| Undocumented: | 3.97 | 2.49,6.34 | 0.001 | 2.17 | 1.04,4.53 | 0.039 |

| WHO category: | ||||||

| First | referent | |||||

| Second | 1.98 | 0.64,6.13 | 0.235 | |||

| Third | 3.54 | 2.08,6.04 | <0.0001 | 2.36 | 1.21,4.58 | 0.011 |

| Fourth | 0.66 | 0.21,2.09 | 0.480 | |||

| Fifth | 13.88 | 1.64,117.60 | 0.016 | 12.55 | 1.16,135.79 | 0.037 |

| Not completing high school | 1.41 | 0.90,2.20 | 0.130 | |||

| Stable housing | 2.13 | 1.34,3.37 | 0.001 | 1.54 | 0.87,2.72 | 0.139 |

| Committed relationship | 1.97 | 1.23,3.14 | 0.004 | 1.28 | 0.71,2.28 | 0.412 |

| Employed | 2.59 | 1.67,4.02 | <0.0001 | 1.33 | 0.73,2.41 | 0.349 |

| Uninsured | 3.09 | 1.83,5.21 | <0.0001 | 1.09 | 0.46,2.60 | 0.834 |

| Injection drug use ever | 0.20 | 0.07,0.58 | 0.003 | 0.41 | 0.10,1.71 | 0.220 |

| Drug use last 30 days: | ||||||

| Any injected | 0.23 | 0.03,1.88 | 0.170 | |||

| Heroin | 0.21 | 0.06,0.70 | 0.012 | 0.40 | 0.08,1.90 | 0.250 |

| Speedball* | n/a | |||||

| Cocaine | 0.32 | 0.12,0.85 | 0.023 | 0.78 | 0.19,3.20 | 0.726 |

| Marijuana | 0.42 | 0.27,0.67 | <0.0001 | 1.80 | 0.53,6.16 | 0.348 |

| Drug use ever: | ||||||

| Heroin | 0.29 | 0.14,0.60 | 0.001 | 1.78 | 0.45,6.98 | 0.408 |

| Speedball | 0.40 | 0.16,1.01 | 0.054 | |||

| Cocaine | 0.39 | 0.23,0.67 | 0.001 | 0.72 | 0.24,2.14 | 0.557 |

| Marijuana | 0.43 | 0.27,0.67 | <0.0001 | 1.51 | 0.66,3.46 | 0.335 |

| Hazardous alcohol use | 1.12 | 0.73,1.72 | 0.610 | |||

| Sex solicitation | 0.86 | 0.48,1.54 | 0.622 | |||

| Exchange for sex | 0.32 | 0.07, 1.48 | 0.144 | |||

| Interpersonal violence victim | 0.45 | 0.19,0.98 | 0.047 | 1.04 | 0.40,2.72 | 0.933 |

| Sexually transmitted infection | 1.12 | 0.64,1.98 | 0.680 | |||

| Mental health diagnosis | 0.88 | 0.48,1.60 | 0.666 | |||

| HIV monoinfected | 2.04 | 0.89,4.70 | 0.093 | |||

| Hepatitis C monoinfected | 0.53 | 0.17,1.69 | 0.286 | |||

| Incarceration recent | 0.47 | 0.22,0.98 | 0.045 | 1.44 | 0.56,3.89 | 0.466 |

| Emergency room recent | 0.58 | 0.32,1.04 | 0.068 | |||

OR: odds ratio; WHO: World Health Organization; IPT: isoniazid preventive therapy

Speedball: injected mixture of cocaine and heroin

Table 3.

Correlates of completing the 9-month course of isoniazid preventive therapy (n=135).

| Bivariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Crude OR | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| DOT (vs SAT) | 1.70 | 0.81,3.57 | 0.157 | |||

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.95,1.00 | 0.088 | 0.97 | 0.94,0.997 | 0.031 |

| Male gender | 1.53 | 0.76,3.08 | 0.235 | |||

| Race/ethnicity: | ||||||

| White | referent | |||||

| Black | 0.93 | 0.16,5.45 | 0.935 | |||

| Asian | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hispanic | 1.33 | 0.25,6.89 | 0.738 | |||

| Foreign-born | 0.55 | 0.22,1.38 | 0.201 | |||

| Undocumented | 1.20 | 0.58,2.46 | 0.621 | |||

| WHO category: | ||||||

| First | referent | |||||

| Second | 0.34 | 0.06,2.01 | 0.235 | |||

| Third | 0.99 | 0.47,2.16 | 0.984 | |||

| Fourth | 0.23 | 0.02,2.31 | 0.211 | |||

| Fifth | 0.68 | 0.13,3.66 | 0.657 | |||

| High school completion | 1.59 | 0.78,3.28 | 0.204 | |||

| Stable housing | 1.02 | 0.48,2.15 | 0.964 | |||

| Committed relationship | 1.05 | 0.50,2.18 | 0.899 | |||

| Employed | 1.43 | 0.71,2.88 | 0.320 | |||

| Uninsured | 1.41 | 0.57,3.47 | 0.454 | |||

| Injection drug use ever | 0.79 | 0.11,5.81 | 0.821 | |||

| Drug use last 30 days¶ | ||||||

| Cocaine | 0.52 | 0.08,3.22 | 0.483 | |||

| Marijuana | 1.63 | 0.29,9.23 | 0.579 | |||

| Ever drug use | ||||||

| Heroin | 1.21 | 0.33,4.53 | 0.769 | |||

| Speedball* | 4.21 | 0.48,37.09 | 0.195 | 11.07 | 0.89,138.0 | 0.062 |

| Cocaine | 0.69 | 0.28,1.69 | 0.414 | |||

| Marijuana | 1.29 | 0.61,2.74 | 0.501 | |||

| Hazardous alcohol use | 0.60 | 0.30,1.19 | 0.145 | 0.58 | 0.28,1.18 | 0.134 |

| Sex solicitation | 1.08 | 0.42,2.76 | 0.873 | |||

| Interpersonal violence victim | 1.36 | 0.31,5.92 | 0.685 | |||

| Sexually transmitted infection | 1.31 | 0.52,3.27 | 0.564 | |||

| Mental health diagnosis | 0.80 | 0.30,2.14 | 0.658 | |||

| HIV monoinfected | 0.66 | 0.21,2.07 | 0.475 | |||

| Hepatitis C monoinfected | 2.45 | 0.25,24.26 | 0.441 | |||

| Incarceration recent | 0.32 | 0.08,1.27 | 0.106 | 0.17 | 0.03,0.89 | 0.036 |

| Emergency room recent | 0.53 | 0.20,142 | 0.208 | |||

OR: odds ratio; DOT: directly observed therapy; SAT: self-administered therapy; WHO: World Health Organization

Speedball: injected mixture of cocaine and heroin

Bivariate analysis was indeterminate for the following due to small sample size: injection drug use last 30 days, heroin use last 30 days, speedball (injected mixture of heroin and cocaine) last 30 days, and ever exchanging sex for money, drugs, or protection.

Acknowledgments

Angel Ojeda, Rolo Lopez, Lisandra Estremera, Elizabeth Roessler PA-C, Ruthanne Marcus, MPH, Natalie Lourenco, PA-C.

Funding: Funding was provided by the National Institutes on Drug Abuse for Career Development (FLA: K24 DA017072; RDB: K23 DA022143) and Research (FLA: R01 DA13805, R01 DA017059, R01 DA029910), The National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (JPM: T32 A1007517-12), and the Gilead Sciences Foundation.

Bibliography

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2012: tuberculosis executive summary. Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Tuberculosis - United States, 2011. MMWR. 2012;61(11):181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackman S. Estimation and inference via Bayesian simulation: an introduction to Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Am J Pol Sci. 2000;44:375–404. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch-Moverman Y, Bethel J, Colson PW, Franks J, El-Sadr W. Predictors of latent tuberculosis infection treatment completion in the United States: an inner city experience. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(9):1104–1111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazar C, Sosa L, Lobato M. Practices and policies of providers testing school-aged children for tuberculosis, Connecticut. J Community Health. 2008;2010(35):495–499. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guh A, Sosa L, Hadler JL, Lobato MN. Missed opportunities to prevent tuberculosis in foreign-born persons, Connecticut, 2005-2008. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(8):1044–1049. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altice FL, Maru DS, Bruce RD, Springer SA, Friedland GH. Superiority of directly administered antiretroviral therapy over self-administered therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(6):770–778. doi: 10.1086/521166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macalino GE, Hogan JW, Mitty JA, Bazerman LB, Delong AK, Loewenthal H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of community-based directly observed therapy as an adherence intervention for HAART among substance users. AIDS. 2007;21(11):1473–1477. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg KM, Litwin A, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Directly observed antiretroviral therapy improves adherence and viral load in drug users attending methadone maintenance clinics: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113(2-3):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruce R, Eiserman J, Acosta A, Gote C, Lim J, Altice F. Developing a modified directly observed therapy intervention for hepatitis C treatment in a methadone maintenance treatment program: implications for program replication. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(3):206–212. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enders C. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebman J, Lamberti P, Altice F. Effectiveness of a mobile medical van in providing screening services for STDs and HIV. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(5):345–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altice FL, Bruce RD, Walton MR, Buitrago MI. Adherence to hepatitis B virus vaccination at syringe exchange sites. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1):151–161. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss L, Netherland J, Egan JE, Flanigan TP, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R, et al. Integration of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment into HIV clinical care: lessons from the BHIVES collaborative. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(S1):S68–75. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a8226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, Lum PJ, Korthuis PT, Flanigan TP, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(S1):S22–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Springer SA, Chen S, Altice FL. Improved HIV and Substance Abuse Treatment Outcomes for Released HIV-Infected Prisoners: The Impact of Buprenorphine Treatment. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):592–602. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan LE, Bruce RD, Altice FL, Haltiwanger D, Lucas GM, Eldred L, et al. Initial strategies for integrating buprenorphine into HIV care settings in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(S4):S191–196. doi: 10.1086/508183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz RK, Bruce RD, Ball SA, Herme M, Altice FL. Comparison of tuberculin skin testing reactivity in opioid-dependent patients seeking treatment with methadone versus buprenorphine: policy implications for tuberculosis screening. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(6):439–444. doi: 10.3109/00952990903447741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maru DS, Bruce RD, Walton M, Springer SA, Altice FL. Persistence of virological benefits following directly administered antiretroviral therapy among drug users: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):176–181. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181938e7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maru DS, Bruce RD, Walton M, Mezger JA, Springer SA, Shield D, et al. Initiation, adherence, and retention in a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(2):284–293. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9336-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altice FL, Mezger JA, Hodges J, Bruce RD, Marinovich A, Walton M, et al. Developing a directly administered antiretroviral therapy intervention for HIV-infected drug users: implications for program replication. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(S5):S376–387. doi: 10.1086/421400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith-Rohrberg D, Mezger J, Walton M, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Impact of enhanced services on virologic outcomes in a directly administered antiretroviral therapy trial for HIV-infected drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(S1):S48–53. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248338.74943.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saber-Tehrani AS, Springer SA, Qiu J, Herme M, Wickersham J, Altice FL. Rationale, study design and sample characteristics of a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community - A potential conduit to improved HIV treatment outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.002. 2010.1016/j.cct.2011.2011.2002. In Press (Epub November 12, 2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventative therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. [November 2012];Tuberculosis Country Profiles. 2011 http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/index.html.

- 26.Stop TB Partnership. [November 2012];Global TB Incidence Rates. 2011 http://www.stoptb.org/assets/images/countries/map_incidence.jpg.

- 27.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salomon N, Perlman D, Friedmann P, Perkins MP, Ziluck V, Des Jarlais D, et al. Knowledge of tuberculosis among drug users relationship to return rates for tuberculosis screening at a syringe exchange. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;16(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salomon N, Perlman D, Friedmann P, Ziluck V, Des Jarlais D. Prevalence and risk factors for positive tuberculin skin tests among active drug users at a syringe exchange program. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(1):47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, Shang N, Gordin F, Bliven-Sizemore E, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]