Abstract

Chitin, obtained principally from crustacean waste, is a sugar-like polymer that is available at low cost. It has been shown to be bio- and ecocompatible, and has a very low level of toxicity. Recently, it has become possible to industrially produce pure chitin crystals, named “chitin nanofibrils” (CN) for their needle-like shape and nanostructured average size (240 × 5 × 7 nm). Due to their specific chemical and physical characteristics, CN may have a range of industrial applications, from its use in biomedical products and biomimetic cosmetics, to biotextiles and health foods. At present, world offshore disposal of this natural waste material is around 250 billion tons per year. It is an underutilized resource and has the potential to supply a wide range of useful products if suitably recycled, thus contributing to sustainable growth and a greener economy.

Keywords: chitin nanofibrils, biomimetic cosmetics, biomedical products, food, nanotechnology, waste

Introduction

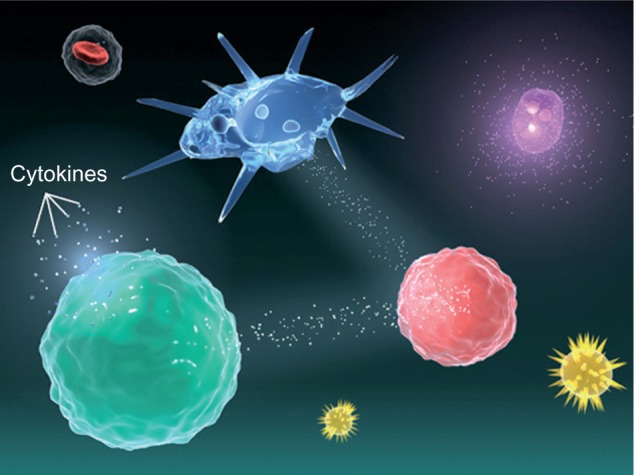

Oligosaccharides, including chitin and chitosan, act as biological messengers for cells.1–3 They induce and regulate defensive, symbiotic, and developmental cellular processes in plants, and probably modulate human cell signals (peptide messengers) by the neuro-immuno-cutaneous-endocrine (NICE) network, activating the nervous, immune, cutaneous, and endocrine systems4–6 (Figure 1). These polyglucosides, such as oligogalacturonic acid, chito-oligosaccharides, and N-acetyl-oligo-glucosamine, act as molecular signals that induce and regulate some genes of plants,7,8 as well as activating human macrophages to produce nitric oxide and other signaling compounds such as reactive oxygen species, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interferon, and interleukin-1.9,10 They seem to have this activity at a cellular level only when in a nanometric structure.

Figure 1.

The peptide messengers.

Chitin and chitosan, as polysaccharides derived from fisheries waste, are available at low cost, and appear to be safe for use in humans in the short- and long-term. In particular, chitin has a very low toxicity and may be used in humans because of its high biocompatibility, ecocompatibility, and degradability. Studies have shown that these natural polymers, obtainable from crustacean and mushroom waste, may be of use in bioconversion for production of food products,11–13 as well as natural biodegradable films to preserve foods from microbial deterioration,14–16 filters for purification of water,17–19 and to produce medical devices.20,21

However, to be more effective at the human level, chitin should be nanostructured if it is to be used as a biological resource for cells. Chitin, an important component of the shells of arthropods and the structure of fungi, can be obtained industrially in the form of pure nanocrystallites using part of the massive amount of biowaste accumulated during marine-capture fisheries, mushroom production, and silk production. Using this easily available raw material is important because of the need to protect the global environment. While worldwide production of chitin has been estimated to be approximately 1011 tons/year (1 trillion/tons), making it one of the most abundant natural compounds on earth,22 a large part of which, obtained as a byproduct of marine fishing, remains unutilized waste.23,24

The production of up to 250 billion tons/year of this waste material is considered hazardous because of its high perishability and high polluting effect both on sea and land. In the sea it rapidly leads to eutrophication with a high oxygen demand, while on land it causes environmental and public health concerns, being quickly colonized by pathogens and spoilage organisms.25–27

Some specific characteristics of nanocrystalline chitin are discussed in this report. In particular, the possible use of this sugar-like compound to improve the cellular metabolism of the skin will be considered.4–6 In addition, its recognition by many human enzymes, which makes it safe when absorbed by the skin or mucous membranes, will also be discussed. Further, this paper will look at the likelihood that chitin is metabolized to glucose, glutamic acid, and/or water and CO2.9,10

Crystalline chitin for biomimetic products

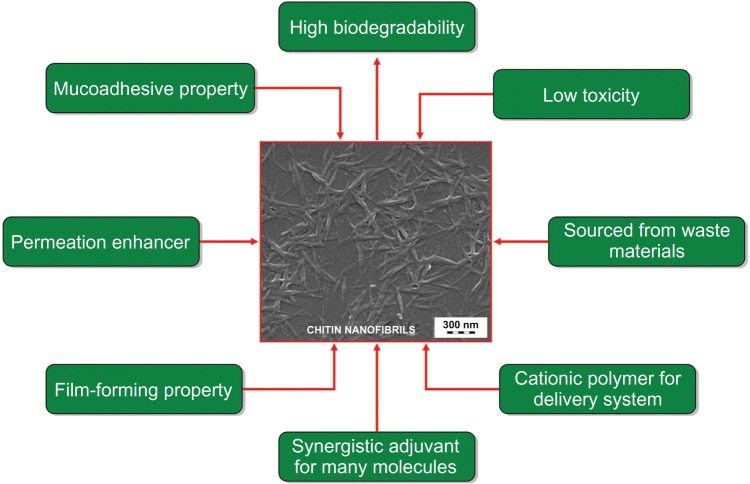

Recently it has become possible to isolate chitin nanocrystals from chitinaceous raw material by an industrial patented process.28 These pure crystals, known as chitin nanofibrils (CN) because of their needle-like shape and nanostructured average size of about 240 × 7 × 5 nm, have an exceptionally high surface area. The nano dimensions of CN, their stability in aqueous solution, and their high molecular pureness, produce many interesting properties (Figure 2). Chitin occurs naturally and is safe to use because, being recognized by human and other enzymes, it is bio- and ecocompatible.29 Many studies are in progress to assess the potential industrial applications for CN, ranging from its use in biomedical products and biomimetic cosmetics, to biotextiles and health food30,31 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Specific characteristics of chitin nanofibrils.

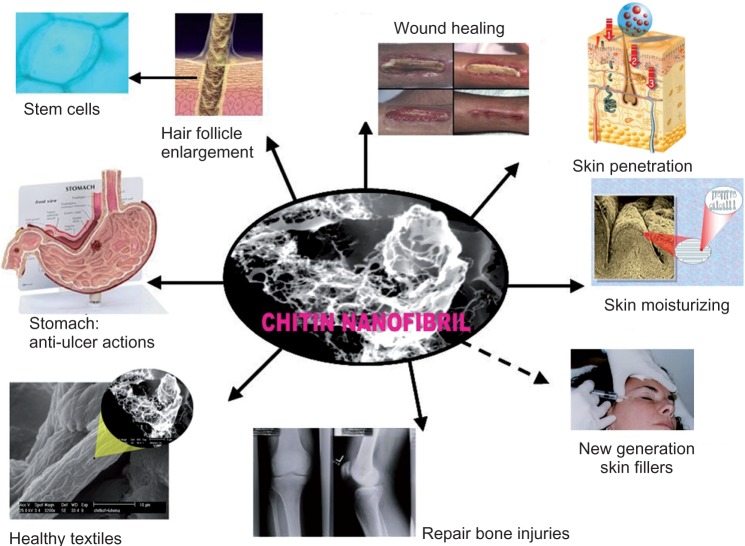

Figure 3.

Chitin nanofibrils and their possible uses.

Biomedical applications

Because wound infections delay healing and worsen scar formation, there is interest in achieving skin closure as soon as possible. CN, incorporated in suitable medical devices manufactured as sprays, gels and gauzes, can perform a fundamental role in the process of tissue granulation.20,21 It promotes and modulates collagen production, avoiding the excessive and irregular synthesis often seen during wound healing. CN also activates cytokines and macrophages, encouraging a physiological reduction of altered scar phenomena such as cheloids and hypertrophic scars.32

Biomimetic cosmetics: the NICE concept

The application of biological methods and systems found in the natural world to the development of engineering systems and modern technology is known as biomimetics. To develop innovative biomimetic technologies, many researchers are studying and applying the so-called NICE concept in the cosmetic field.33–36 These systems are all involved in the global face-body activity a cosmetic has when applied to the skin. In vitro and in vivo studies have been used to investigate and understand the information systems body cells use to communicate with each other in the skin. CN seems to represent a multilevel active/vehicle material that can help solve this fascinating problem. Hands-on training workshops and meetings have been organized and reported by our group to disseminate recently obtained results on the use of this nanostructured natural compound.37–42 Further dissemination of results is ongoing along with the development of new applications.

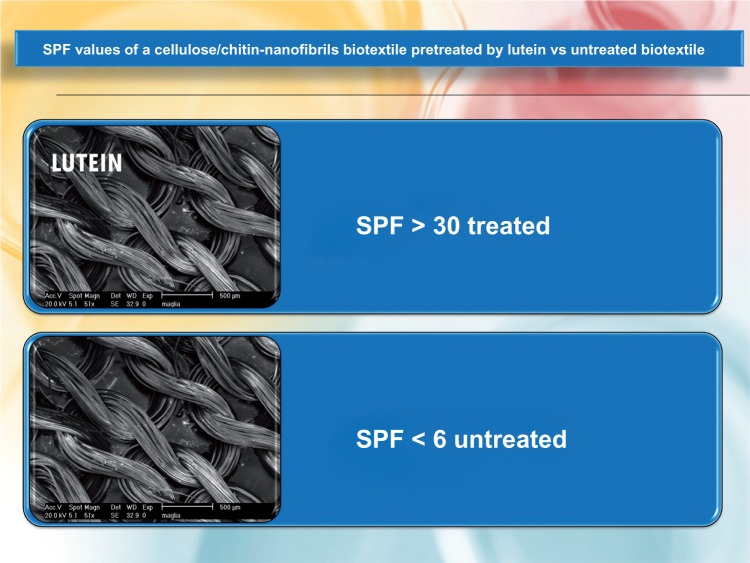

Biotextiles: mimicking the cell signal

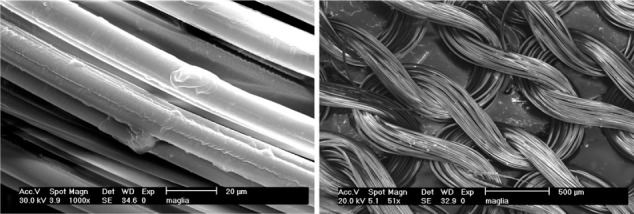

Skin cells are continuously bombarded with different signals from inside and outside. Studying and quantifying these signals will help us to better understand skin turnover and life cycle, and facilitate our understanding of the many applications intelligent cosmetics and drugs could have by mimicking these signals. Similarly, there is current interest in biofunctional textiles, focused on the use of special fibres to support therapies and preventative techniques in dermatology. These special textiles, interacting with the skin surface by the NICE approach, should have not only a general protective biological activity but may possess, for example, a more specific function against UVA radiation and thus an antiaging efficacy, or could possess antimicrobial effects protecting wounds from nosocomial and other pathogenic fora.43 With this intent, CN, prelinked with lutein, has been incorporated into fibres of cellulose acetate to produce a biotextile with an anti-UVA and blue light–screening activity (Figure 4). In humans there are a variety of abnormal photosensitivity responses to sunlight that may result from either endogenous imbalances (eg, the porphyrias) or from added exogenous factors (eg, drug photosensitivity). These responses are elicited predominantly by long UVA and, in some cases, by blue and visible light.44 The effect of lutein in reducing damage from UVA and blue light has already been clearly demonstrated.45–47 The first results obtained with the use of an anti-UVA biotextile and a nonwoven bactericidal tissue produced at lab level are reported in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Photoprotective fibers and biotextiles obtained by electrospinning of cellulose and chitin nanofibrils.

Figure 5.

The ultraviolet A protective activity of lutein-biotextile.

Abbreviation: SPF, sun protection factor.

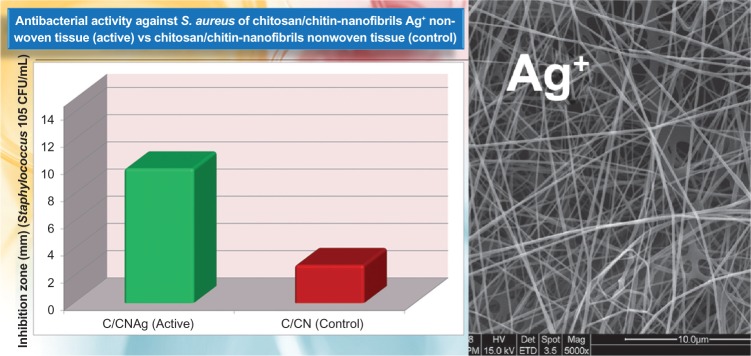

In addition, antimicrobial nonwoven nanofibers made of polyvinyl alcohol, chitosan, and CN prelinked with bioactive nanostructured Ag+ ions have been developed for medical and hygienic tasks (Figure 6). The silver ion is biologically active and readily interacts with proteins, amino acid residues, free anions and receptors on microorganism, and human cell membranes. However, this metal, especially when nanostructured and in the ionic form, exerts an antimicrobial action at concentrations so low (1 ppm) as to be entirely safe. It exhibits an oligodynamic effect because its metabolism is modulated by induction and binding to metallothioneins.48

Figure 6.

Antibacterial activity of chitosan/chitin fibers Ag+ treated.

Abbreviations:S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; C, chitosan; CN, chitin-nanofibrils; CFU, colony forming unit.

Dealing with food contaminants: the future challenge

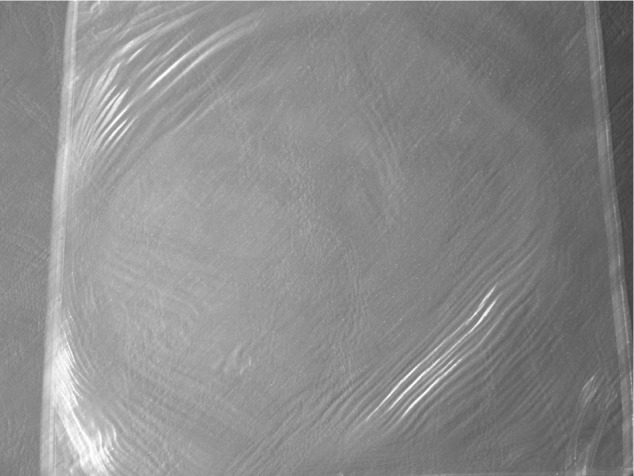

It is vital that all surfaces that come in contact with food and foodstuffs are free of potentially hazardous microorganisms. It has been found that, compared with conventional antimicrobial films made of polyethylene, a polymeric biocide film of CN-chitosan has the advantage of being elastic, with high tensile strength. It is also chemically stable and totally bio-and ecodegradable, being only composed of polyglucosides (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Edible film for food covering.

Additionally, chitosan and chito-oligosaccharides (COS), with a shorter chain of two to ten units of d-glucosamine, have the potential to be used as prebiotics for the formulation of functional food.49 They exhibit a bifidogenic effect at concentrations between 0.1% and 0.5%, being not digestible by intestinal enzymes. According to a recent study on the cecum of mice treated with COS for 14 days50 and in agreement with the authors, the concentrations of more favorable bifidobacteria and lactobacilli increased, while reducing the concentrations of unfavorable Enterococcus and Enterobacteriaceae. Already, glucosamine is sold and recommended as a dietary supplement for the prevention and management in osteoarthritis, while chitosan is used for obesity control and hypercholesterolemia treatment. It is not surprising that chitin, CN-chitosan, and the crystalline CN of crustacean and/or fungal origin should also have a nutritional role.

The need to protect production processes and trademarks

In a globalized world, while it is of fundamental importance to use waste materials to save the environment, it is also necessary to protect both the production processes and trademarks with patents, to permit industrial expansion via licensing and joint ventures. “The ordinary goal of trademark licensing is to allow the licensor to expand its existing business or create a new one.”51 It is necessary to control the good standing of a licensee company by using an expert in the field of licensed products and intellectual properties.

The potential uses of CN and its derivatives as nanostructured natural compounds patented for their production processes and uses51 have yet to be fully developed. More cooperative research studies between industries and academia, together with legal strategies, will be vital for successful development of innovative products protected with patents from the ever-growing phenomenon of counterfeiting.52

Conclusion

It seems possible to use chitinaceous waste material to produce health products53,54 including biomedical, cosmetic, and textile products, along with food or food supplements. Use of this material not only reduces environmental pollution but also, according to Drexler et al55 allows us to reduce, recycle, and transform waste material into food with the help of nanotechnology, allowing sustainable growth and greener industry.

Footnotes

Disclosure

G Morganti and P Morganti are employees of MAVI Sud in the Centre of Nanosciences and were involved in the studies on chitin nanofibrils. A Morganti has no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Darvile A, Augur C, Bergmann C, et al. Oligosaccharins-oligosaccharides that regulate growth, development and defence responses in plants. Glycobiology. 1992;2(3):181–198. doi: 10.1093/glycob/2.3.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cote F, Hahn MG. Oligosaccharins: structure and signal transduction. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26(5):1379–1411. doi: 10.1007/BF00016481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John M, Rohrig H, Schmidt J, et al. Cell signaling by oligosaccharides. Trends in Plant Science. 1997;2(3):111–115. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morganti P, Li YH, Chen HD. NICE melody for innovative mind-body skin care. Cosmetic Science Technology. 2011;21:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morganti P, Chen H-D. Skin cell management: the NICE approach. Personal Care. 2011;4(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morganti P, Li YH, Morganti G. Nanostructured products: technology and future. J Plastic Dermatology. 2008;4(3):253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lerouge P, Roche P, Faucher C, et al. Symbiotic host-specificity of Rhizobium meliloti is determined by a sulfated and acylated glucosamine oligosaccharides signal. Nature. 1990;344(6268):781–784. doi: 10.1038/344781a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dzung N. Enhancing crop production with chitosan and its derivatives. In: Se-Kwon Kim., editor. Chitin, Chitosan, Oligosaccharides and their Derivatives. New York: CRC Press; 2010. pp. 619–631. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muzzarelli RAA. Human enzymatic activities related to the therapeutic administration of chitin derivatives. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1997;53(2):131–140. doi: 10.1007/PL00000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori T, Okumura M, Matsuura M, et al. Effects of chitin and its derivatives on proliferation and cytokine production of fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 1997;18(13):947–951. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(97)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroad PA, Tom RA. Bioconversion of shellfish chitin wastes: Process conception and selection of microorganisms. J Food Sci. 1978;43:1158–1161. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Revah-Moiseev S, Carroad A. Conversion of the enzymatic hydrolase of shell-fish waste chitin to single-cell protein. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1981;23:1067–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaidi F, Synowiecki J. Isolation and characterization of nutrients and value-added products from snow crab (Chitinocetes opilio) and shrimp (Pandalus borealis) processing discards. J Agric Food Chem. 1991;39:1527–1532. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faug SW, Li CF, Shih DYC. Antifungal activity of chitosan and its preservative effect on low-sugar candied kumquat. J Food Prot. 1994;56:136–140. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CS, Liau WY, Tsai GJ. Antibacterial effects of N-sulfonated and N-sulfobenzoyl chitosan and application to oyster preservation. J Food Prot. 1998;61(9):1124–1128. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.9.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kittur FS, Kumar KR, Tharanathan RN. Functional packaging properties of chitosan films. Z Lesbensur Unters Forsch. A. 1998;206:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guibal F. Interactions of metal ions with chitosan-based sorbents. A review. Sep Purif Technol. 2004;38:43–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crini G. Recent developments in polysaccharide-based materials used as adsorbents in wastewater treatment. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;(30):3870. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crini G. Non-conventional low-cost adsorbents for dye removal: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:1061–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muzzarelli RAA, Morganti P, Morganti G, et al. Chitin nanofibrils/chitosan glycolate composites as wound medicaments. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2007;70(3):274–284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biagini G, Zizzi A, Tucci G, et al. Chitin nanofibrils linked to chitosan glycolate as spray, gel and gauze preparations for wound repair. J Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 2007;22:525–538. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurita K. Chitin and chitosan: functional biopolymers from marine crustaceans. Mar Biotechnol. 2006;8:203–226. doi: 10.1007/s10126-005-0097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations Statistics [databases on the Internet] Rome: FAO; 2011Available at: http://www.fao.org/fshery/statistics/enAccessed September 22, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SK, Mendis E. Bioactive compounds from marine processing bioproducts: a review. Food Res Int. 2006;39:383–393. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Islam M, Khan S, Tanaka M. Waste loading in shrimp and fish processing effluents: Potential source of hazards to the coastal and nearshore environments. Mar Pollut Bull. 2004;19:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaney P, Lizardi-Mendoza J, Healy M. Comparison of chitins produced by chemical and bioprocessing methods. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2005;80:145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruck WM, Slater JW, Carney BF. Chitin and chitosan from marine organisms. In: Kim SK, editor. Chitin, Chitosan, Oligosaccharides and their Derivatives. New York: CRC Press; 2010. pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.MAVI Sud International Patent. Chitin nanofibrils : a natural compound to be used as a drug. 2002. PCT/IB2005/053576.

- 29.Morganti P. Chitin-nanofibrils in skin treatment. J Appl Cosmetol. 2009;27:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morganti P, Chen HD, Gao HA, et al. Nanoscience challenging cosmetics, healthy food and biotextiles. SOFW-Journal. 2009;135(4):32–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morganti P. Beauty from inside and outside Natural products work in multiple ways. In: Tabor A, Blair R, editors. Nutritional Cosmetics Beauty from Within. New York: William Andrew (Elsevier); 2009. pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mezzana P. Clinical efficacy of a new chitin nanofibrils-based gel in wound healing. Acta Chir Plast. 2008;50(3):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosoi J, Murphy GF, Egan CL, et al. Regulation of Langerhans cell function by nerves containing calciotonin gene-related peptide. Nature. 1993;363(6425):159–163. doi: 10.1038/363159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torii H, Yan Z, Hosoi J, Granstein RD. Expression of neurotrophic factors and neuropeptides receptors by Langerhans cells and Langerhans cell-like XS52: Further support for a functional relationship between Langerhans cells and epidermal nerves. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;109(4):588–549. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12337516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brazzini B, Ghersetich I, Hercogova J, Lotti T. The neuro-immunocutaneous network relationship between mind and skin. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16(2):123–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8019.2003.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hosoi J. NICE network-evidence and application to cosmetics. J Appl Cosmetol. 2011;29:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morganti P. Applied Nanotechnology in cosmetic and functional food; Paper presented at CHI 2006 – Market Trends; Warsaw. Oct 25–26, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morganti P. Chitin nanofibrils: an innovative/natural raw material; SCS 100% Natural Conference; Staverton Park, Northants, UK. May 13–15, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morganti P. Chitin nanofibrils: a natural compound with a multiform use; Primavera Italiana; Giappone, Tokyo. May 17–18, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morganti P. Chitin nanofibrils: a new natural compound patented by Mavi. Santa Clara, CA: May 20–24, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morganti P. Nanostructured products: technology and future. Beijng, China: Oct 20–23, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morganti P. Nanoscience: The challenging cosmetics, healthy food and biotexiles. Zhengzou: Sep 17–19, 2008. Dallas, TX, October2–3; Barcelona, October 23; Warsaw, Nov 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mòfer D. Antimicrobial textiles-evaluation of their effectiveness and safety. In: Hipler U-C, Elsner E, editors. Biofunctional Textiles and the Skin. Basel: Karger; 2006. pp. 42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menter JM, Kathryn LH. Clothing as solar radiation protection. In: Elsner P, Hatch R, Wigger-Alberti W, editors. Textiles and the Skin. Basel: Karger; 2003. pp. 50–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sujak A, Gabrielska J, Grudzinski W, Borc R, Mazurek P, Gruszecki W. Lutein and zeaxanthin as protectors of lipid membranes against oxidative damage: the structural aspects. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;371(2):301–307. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roberts RL, Green J, Lewis B. Lutein and zeaxanthin in eye and skin health. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morganti P. The photoprotective activity of nutraceuticals. Clin Dermatol. 2009;27(2):166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lansdown ABG . Silver in health care: antimicrobial effects and safety use. In: Hipler U-C, Elsner P, editors. Biofunctional Textiles and the Skin. Basel: Karger; 2006. pp. 17–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vidanarachchi JK, Kurukulasuriya MS, Kim SK. Chitin, chitosan, and their oligosaccharides in food industry. In: Kim SK, editor. Chitin, Chitosan, Oligosaccharides and their Derivatives. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2010. pp. 543–560. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan X, Chen F, Wut, et al. Prebiotic oligosaccharides change the concentration of short chain fatty acids and the microbial population of mouse bowel. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2009;10(4):258–263. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morganti P. MAVI Sud Int patent PCT/IB2005/053576.

- 52.Morganti A, Klein A, Borrini S, Rubino G, Roncaglia PL. The protection of intellectual property. J Appl Cosmetol. 2009;27:209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morganti P. Chitin nanofibrils and their derivatives as cosmeceuticals. In: Kim SK, editor. Chitin, Chitosan, Oligosaccharides, and their Derivatives. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morganti P, Del Ciotto P, Morganti G, Fabien-Soulè V. Application of chitin nanofibrils and collagen of marine origin as bioactive ingredients. In: Kim SK, editor. Marine Cosmeceuticals: Latest Trends and Perspectives. New York, NY: CRC-Press; 2011. pp. 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drexler E, Peterson C, Pergamit G. Unbounding the Future: The Nanotechnology Revolution. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company; 1991. [Google Scholar]