Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Coronary artery aneurysm is a rare condition with a reported incidence of 0.14–4.9% in patients undergoing coronary angiography and 0.3–5.3% in patients after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). Optimum surgical therapy for this entity is difficult to standardize. We present here a series of 4 cases with the aim of establishing an optimal surgical therapy for this rare entity.

METHODS

Four cases of coronary artery aneurysm were admitted in the Department of Cardiology and Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, King George's Medical University, Lucknow, from April 2010 to April 2012. All patients underwent a surgical procedure that involved ligation and plication of the aneurysm with coronary artery bypass grafting.

RESULTS

Out of the four coronary artery aneurysm patients, 1 was atherosclerotic and the remaining 3 patients developed coronary artery aneurysm after PTCA with a drug eluting stent to the left anterior descending artery. After surgery, all patients recovered uneventfully without any recurrence of symptoms in the follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Coronary artery aneurysm is a rare entity and is being seen more frequently with the increasing use of stents during PTCA. Proximal ligation and plication of the aneurysm with coronary artery bypass grafting in the present series provided good results. With this case series, we seek to establish an optimal surgical therapy for this rare entity.

Keywords: Aneurysm (Coronary), Stents (Coronary), Coronary percutaneous intervention, Coronary artery bypass grafting

INTRODUCTION

Aneurysmal dilatation of the coronary arteries was first described by Bourgon in 1812 [1]. Since then, numerous isolated case reports and small series of patients have been described [2, 3]. Coronary artery aneurysm (CAA), defined as dilatation of the coronary artery exceeding 50% of the reference vessel diameter, is uncommon and occurs in 5% of coronary angiographic series [4]. CAAs are termed giant if their diameter exceeds the reference vessel diameter by >4 times or if they are >8 mm in diameter [5]. Up to one-third of CAAs are associated with obstructive coronary artery disease and have been associated with myocardial infarction, arrhythmias or sudden cardiac death [6]. Post-coronary intervention aneurysms are rare but are being seen with increasing frequency. The therapy for these aneurysms is still debatable. For the first time, we are reporting 4 cases of coronary aneurysm from a single centre with their surgical results with the aim of establishing an optimum surgical therapy for coronary aneurysms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was done between April 2010 to April 2012 in the Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery and Cardiology in 4 patients of coronary aneurysm. The clinical details of the patients are given in Table 1. The case summary of the patients is as follows:

Table 1:

Clinical details of the patient

| Case | Age (year)/sex | Cause | Risk factors | Site | Size (cm) | Intervala (months) | Stent | Surgical procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50/male | Iatrogenic (post-stenting) | DM, HT, smoker | Proximal, LAD | 2.5 × 2.5 | 3 | Endeavor | Proximal ligation of aneurysm + OPCABG (LIMA to LAD) |

| 2 | 75/male | Iatrogenic (post-stenting) | DM, HT, smoker | Proximal, LAD | 2 × 2 | 1 | Taxcor | Proximal ligation and plication of aneurysm + OPCABG (LIMA to LAD) |

| 3 | 73/male | Iatrogenic (post-stenting) | DM, HT, smoker | Mid-LAD | 2 × 2 | 24 | Xience | Proximal ligation and plication of aneurysm + On-pump beating heart CABG (rSVG to LAD) |

| 4 | 60/male | Atherosclerosis | HT, smoker | Proximal, LAD | 1.5 × 1.5 | – | – | Proximal ligation and plication of aneurysm + OPCABG (rSVG sequential to D1 and LAD) |

aBetween percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography and aneurysm formation.

DM: diabetes mellitus; HT: hypertension; LAD: left anterior descending; LIMA: left internal mammary artery; OPCABG: off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting; rSVG: reverse sephanous vein graft.

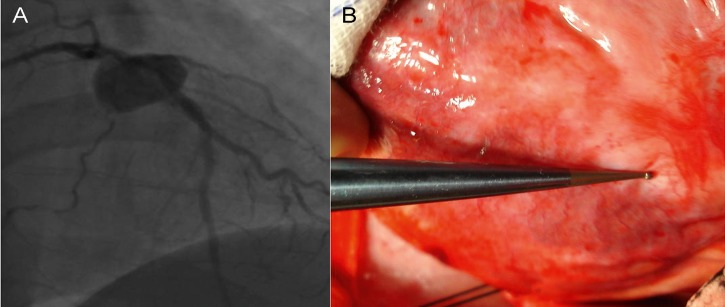

Case 1

A 50-year old male diabetic, hypertensive, non-smoker presented with a history of worsening of angina despite full medical therapy. His 2D echocardiography (2D Echo) showed no wall motion abnormality with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. His coronary angiography showed a right coronary artery total occlusion and a mid-left anterior descending (LAD) 99% lesion. After informed consent, a decision for revascularization of the LAD with a drug eluting stent was taken and subsequently a 3.5 × 30 mm Endeavor stent (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was deployed at 14 atm pressure with good throbolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)-3 flow. He was discharged on the second day on dual antiplatelet therapy along with atorvastatin 80 mg and metoprolol 100 mg, along with oral antihyperglycemic drugs. Three months later, the patient had an episode of high-grade fever with chills and left precordial pain which was constant and dull aching and had a dragging character. The repeat angiography showed an aneurysmal dilatation ∼2.5 cm in size in the proximal part of the LAD where the stent had been deployed along with lesion proximal to the stent (Fig. 1A). He was advised to undergo an emergent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and resection of the aneurysmal sac. During surgery, a large aneurysm of the proximal LAD ∼2.5 cm in diameter was noted. It was proximally ligated and a left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft to the LAD used to bypass the lesion (Fig. 1B). He is now well on follow-up after 2 years.

Figure 1:

Coronary angiography reveals a coronary aneurysm of 2.5 cm in diameter in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery (A). Intraoperative photograph showing coronary aneurysm in the proximal LAD (B) (Source: Indian Heart Journal 2012;6402:198–9, permission: obtained).

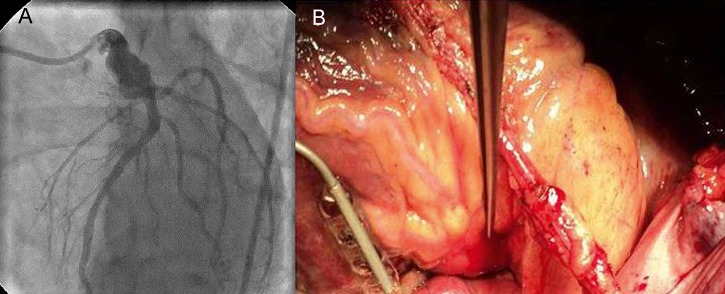

Case 2

A 75-year old male smoker who is a diabetic and hypertensive with a past history of chronic stable angina for which stenting of the LAD with a Taxcor stent (Euro GmbH, Germany) 3 × 28 at 10 atm with TIMI-3 flow was done at a private hospital presented with acute coronary syndrome 1 month after stenting. Control angiography was done at the same place which showed LAD stent patent with a 2 × 2 cm aneurysm in the proximal LAD (Fig. 2A). The patient was referred to us for surgical management. During surgery, a 2 × 2 cm size aneurysm in the proximal LAD was found. It was proximally ligated and plicated and a LIMA graft was used to bypass the lesion on beating heart (Fig. 2B). His postoperative period was uneventful and he was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. The patient is doing well on follow-up with no recurrence of symptoms

Figure 2:

Coronary angiography reveals a coronary aneurysm of 3 × 2 cm size in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery (A). Intraoperative photograph of Patient 2 reveals coronary aneurysm of 3 × 2 cm size in the proximal LAD. Off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCABG) × 1 (LIMA to LAD) has been done (B).

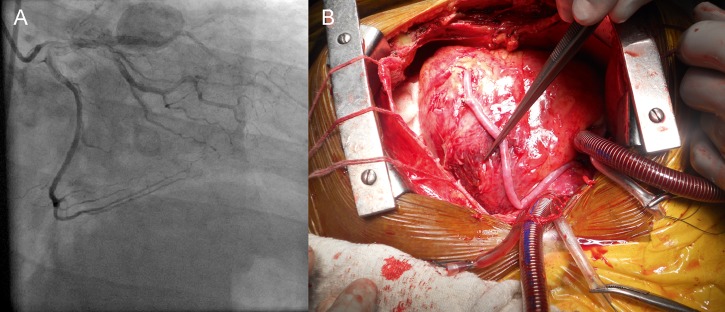

Case 3

A 73-year old male diabetic, hypertensive and a follow-up case of old non-segment (ST) elevation myocardial infarction with drug eluting stenting to the LAD and ramus intermedius with a Xience V stent (Abott Laboratories, IL, USA) 2.75 × 28 in September 2009 presented with sudden-onset chest pain on September 2011. His 2D Echo showed hypokinesia of the LAD territory. His coronary angiography showed 100% in-stent restenosis in the LAD stent with a 3 × 2 cm aneurysm in the mid-LAD (Fig. 3A). He was managed medically with dual antiplatelet therapy with atorvastatin, metoprolol and oral hypoglycaemic drugs. After stabilization, the patient was referred to us for surgical management. During surgery, a large aneurysm of 2 × 2 cm in the mid-LAD was found. Our attempt to harvest LIMA was not successful because of dense pericardial adhesions for which the patient was taken on bypass and on-pump beating heart CABG was performed. Aneurysm was proximally ligated and plicated and reverse saphenous vein graft (SVG) was used to bypass the lesion (Fig. 3B). The patient was discharged 6 days after surgery and is well now after 6 months of the follow-up.

Figure 3:

Coronary angiography reveals a coronary aneurysm of 2 × 2 cm size in the mid-left anterior descending (LAD) artery (A). Intraoperative photograph showing coronary aneurysm of 2 × 2 cm size in the mid-LAD. On-pump beating heart coronary artery bypass grafting (rSVG to the distal LAD) has been done (B).

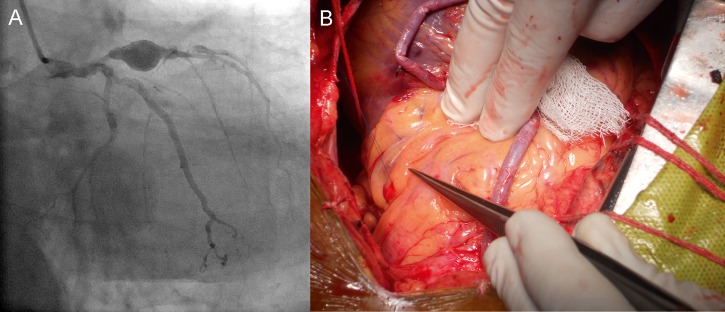

Case 4

A 60-year old male hypertensive and smoker presented with a history of angina on exertion for the last 3 years and rest pain for the last 2 days. Electrocardiography on admission showed ST depression in leads V5 and V6. His 2D Echo showed no abnormality. His coronary angiography showed a proximal LAD aneurysm of 9 × 11 mm with 50% occlusion of the left main coronary artery, 70% occlusion of the LAD and 70% occlusion of the distal left circumflex (Fig. 4A). The patient was managed medically and was referred to us for surgical management. During surgery, an aneurysm of 1.5 × 1.5 cm was found in the proximal LAD. Immediately after sternotomy, the patient had haemodynamic instability which settled gradually and it was decided on table to graft the LAD with SVG (which was already harvested by that time. Aneurysm was proximally ligated and plicated and beating heart CABG (sequential SVG graft to LAD and D1) was done to bypass the lesion (Fig. 4B). His postoperative period was uneventful and he was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. The patient is doing well after 6 months of follow-up.

Figure 4:

Coronary angiography of Patient 4 reveals a coronary aneurysm of 1.5 × 1.5 cm size in the proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery (A). Intraoperative photograph showing coronary aneurysm of 1.5 × 1.5 cm size in the proximal LAD. Off-pump beating heart coronary artery bypass grafting (rSVG to LAD) has been done (B).

RESULTS

The postoperative course was uneventful. The postoperative data are given in Table 2. Only 2 patients required ionotropic support postoperatively. The mean ventilation time was 6.25 h and mean mediastinal drainage was 287.5 ml. None of the patients required transfusion of any blood product. All patients had an intensive care unit stay of 2 days and a hospital stay of 5–6 days. All the patients recovered satisfactorily and were discharged. During the follow-up, all the patients were found to be free of symptoms and none died during the follow-up. All the patients were followed up clinically and a non-invasive follow-up with electrographically controlled exercise test was done, which showed no reversible ischaemia in either of the cases.

Table 2:

Postoperative data of the patients

| Case | Ventilation time | Reintubation | Ionotropic requirement | Adverse event | Total blood loss | Blood product transfused |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 h | No | No | No | 200 ml | None |

| 2 | 7 h | No | Yes | No | 300 ml | None |

| 3 | 7 h | No | Yes | No | 350 ml | None |

| 4 | 6 h | No | No | No | 200 ml | None |

DISCUSSION

CAA is an uncommon entity although it has been diagnosed with increasing frequency since the advent of coronary angiography. This is the first case report describing surgical therapy in 4 cases of coronary aneurysm from a single centre.

Based on several angiographic studies, the incidence of CAAs ranges widely from 0.3 to 5.3% of the population, and a pooled analysis reports a mean incidence of 1.65% [7]. CAAs after coronary intervention are rare, with a reported incidence of 0.3–6.0%, and most aneurysms are in fact pseudoaneurysms rather than true aneurysms [8].

In all our 4 cases, coronary aneurysm developed in the LAD artery. The reason for the preferential development of CAA in the LAD is the same as that for preferential development of atherosclerosis in the LAD. LAD segments are exposed to higher wall stress during systole. This is the result of the different contractile properties of the left vs right ventricle. Moreover, the LAD exhibits twice the torsion of other arteries generating helical flow patterns. Furthermore, the increasing branching pattern of the LAD contributes to the development of disturbed flow [9].

Typical causes of aneurysms include congenital [10] Kawasaki disease, atherosclerosis and coronary trauma. Less common causes are polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis and rheumatic fever [11].

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) occasionally causes the unexpected adverse effect of a CAA, which is prone to rupture and thrombose and therefore requires repair [12]. With the increasing use of new devices, and newer ones appearing in quick succession, an increase in the frequency of this complication is expected. PTCA-induced pseudoaneurysm of the coronary artery is caused either by incomplete healing after perforation or by rupture of the coronary artery occurring at the time of the coronary intervention. According to a report by Ajluni et al. [13], perforation associated with conventional PTCA occurred in 0.14% of cases.

In the Taxus-V trial, CAAs were more prevalent after implantation of paclitaxel-eluting stents than bare metal stents (1.4 vs 0.2%), though this trend did not quite achieve statistical significance (P < 0.07) [14]. This did not appear to be due to differences in pressure during deployment or stent size, suggesting that aneurysms may be the result of an inflammatory reaction to the drug-coated stent [15]. The antiproliferative mechanism of the anticancer drugs were thought to cause impaired healing effect, which ultimately may be counter-productive and lead to the formation of CAA [16, 17].

Coronary intervention-associated aneurysms usually are detected at the time of repeat angiography for recurrent symptoms or as part of routine angiographic follow-up as mandated by study protocols.

Coronary angiography is the gold standard for the diagnosis of coronary aneurysms, which are defined as a luminal dilatation 50% larger than that of the adjacent reference segment [4]. Intravascular ultrasound has become the gold standard in providing critical diagnostic information to address the anatomic considerations in the evaluation of coronary aneurysms [18].

Aoki et al. [16] have proposed a classification system for coronary aneurysm that forms after coronary stenting. Type I aneurysm is a type of aneurysm that demonstrates rapid early growth with pseudoaneurysm formation detected within 4 weeks. It is likely that arterial injury related to the procedure is the likely contributor to aneurysm formation in these cases. Type II aneurysm is a type of aneurysm with a sub-acute to chronic presentation and is typically detected incidentally during angiography for recurrent symptoms or as part of protocol mandated follow-up (usually detected ≥6 months after the procedure). Type III subtype in the published literature is mycotic or infectious in aetiology. In these rare cases, patients typically present with systemic manifestations and fever as the result of bacteraemia.

The impetus for treating coronary aneurysms is predicated on the host of complications associated with these lesions. These most commonly include angina, myocardial infarction and sudden death. Other adverse events include thrombosis, thromboembolism, formation of arterio-venous fistulae, vasospasm and rupture. These complications may, in part, be related to turbulent flow associated with aneurysms, though they could also be attendant features of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease that tend to be seen in association with aneurysms.

The management of patients with CAA is controversial. There are few data regarding medical therapy for coronary aneurysms. Medical management generally includes antiplatelet and/or antithrombotic agents, the use of which has been anecdotal.

Concerns relating to stent graft treatment of coronary aneurysms include closure of contiguous side branches arising next to the aneurysm site, stent thrombosis and recurrent restenosis. Placing coronary coils behind stents to thrombose the aneurysm sac can also be challenging and requires considerable expertise. Poly-tetra flouro ethylene (PTFE) covered stents which are easy and rapid to deploy have emerged as a new tool for the treatment of CAAs [19, 20]. However, some multicentre randomized trials in comparing expanded PTFE stent graft with bare metal stents have shown that these stents do not improve clinical outcomes and may be associated with a higher incidence of restenosis and early thrombosis [21]. There have been very few case reports of treatment of CAA with covered stent graft and the technique is still in the evolving phase [22].

Surgical approach is thought to be safer and more reliable for repair of a coronary aneurysm/pseudoaneurysm. The indications for the surgical treatment of CAA in general are (i) severe coronary stenosis, (ii) complications such as fistula formation, (iii) compression of the cardiac chambers, (iv) high likelihood of rupture such as rapidly increasing size of the aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm and (v) any type of aneurysm developing after coronary intervention [23, 24].

Operative therapy may include aneurysm ligation, resection or marsupialization with interposition graft, and the ideal approach has not yet been formally studied [25].

In our 3 cases of coronary aneurysm, a common surgical technique was employed which included proximal ligation, plication and revascularization. In 1 case, proximal ligation and revascularization was done.

In conclusion, the treatment for coronary artery aneurysm is still controversial. We propose that post-stenting aneurysms (with or without coronary stenosis), expanding aneurysms/pseudonaneurysms, infected aneurysms and symptomatic aneurysms should be surgically treated. The optimum surgical therapy for coronary aneurysms includes proximal ligation, plication and revascularization. Results after surgical therapy are excellent.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to K. Sarat Chandra, Hony. Editor, Indian Heart Journal for giving us permission to use photographs from Indian Heart Journal.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bourgon A., Scott DH. Aneurysm of the coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 1948;36:403. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(48)90337-8. Biblioth Med. 1812; 37: 183 cited by. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markis JE, Joffe CD, Cohn PF, Feen DJ, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Clinical significance of coronary arterial ectasia. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:217. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van den Broek H, Segal BL. Coronary aneurysms in a young woman: angiographic documentation of the natural course. Chest. 1973;64:132. doi: 10.1378/chest.64.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syed M, Lesch M. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1997;40:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(97)80024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugimura T, Kato H, Inoue O, Takagi J, Fukuda T, Sato N. Long-term consequences of Kawasaki disease: a 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation. 1996;94:1379–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Indolfi C, Achille F, Tagliamonte G, Spaccarotella C, Mongiardo A, Ferraro A. Polytetrafluoroethylene stent deployment for a left anterior descending coronary aneurysm complicated by late acute anterior myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:e70–1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.497891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartnell GG, Parnell BM, Pridie RB. Coronary artery ectasia: its prevalence and clinical significance in 4993 patients. Br Heart J. 1985;54:392–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.54.4.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell MR, Garratt KN, Bresnahan JF, Edwards WD, Holmes DR., Jr Relation of deep arterial resection and coronary artery aneurysms after directional coronary atherectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1474–81. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90439-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannoglou GD, Antoniadis AP, Chatzizisis YS, Louridas GE. Difference in the topography of atherosclerosis in the left versus right coronary artery in patients referred for coronary angiography. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-10-26. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berdajs D, Ruchat P, Suva M, Ferrari E, Ligang L, Von Segesses LK. Congenital giant aneurysm of the left coronary artery. Heart Lung Circulation. 2011;20:663–5. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, Vignola PA, Judkins MP, Kemp HG, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983;67:134–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anabtawi IN, de Leon JA. Arteriosclerotic aneurysms of the coronary arteries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;68:226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajluni SC, Glazier S, Blankenship L, O'Nell WW, Safian RD. Perforations after percutaneous coronary interventions: clinical, angiographic, and therapeutic observations. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;32:206–12. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cannon L, Mann JT, Greenberg JD, Spriggs D, et al. Comparison of a polymer-based paclitaxel-eluting stent with a bare metal stent in patients with complex coronary artery disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:1215–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bavry AA, Chiu JH, Jefferson BK, Karha J, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG, et al. Development of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent implantation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:230–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aoki J, Kirtane A, Leon MB, Dangas G. Coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2008;1:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saran RK, Dwivedi SK, Puri A, Sethi R, Agarwal SK. Giant coronary artery aneurysm following implantation of Endeavour stent presenting with fever. Indian Heart J. 2012;6402:198–9. doi: 10.1016/S0019-4832(12)60061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porto I, MacDonald S, Banning AP. Intravascular ultrasound as a significant tool for diagnosis and management of coronary aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:666–8. doi: 10.1007/s00270-004-0038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szalat A, Durst R, Cohen A, Lotan C. Use of polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent for treatment of coronary artery aneurysm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:203–8. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MS, Nero T, Makkar RR, Wilentz JR. Treatment of coronary aneurysm in acute myocardial infarction with AngioJet thrombectomy and JoStent coronary stent graft. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:294–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schachinger V, Hamm CW, Munzel T, Haude M, Baldus S, Grube E, et al. A randomized trial of polytetrafluoroethylenemembrane covered stents compared with conventional stents in aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1360–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bajaj S, Parikh R, Hamdan A, Bikkina M. Covered-stent treatment of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent placement: case report and literature review. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37:449–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi H, Yamauchi H, Yamada T, Ariyoshi T. Surgical repair of coronary artery aneurysm after percutaneous coronary intervention. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:52–5. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradbury AW, Milne A, Murie JA. Surgical aspects of Behçet's disease. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1712–21. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harandi S, Johnston SB, Wood RE, Roberts WC. Operative therapy of coronary arterial aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1290–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]