Abstract

This study analyzes injuries occurring prospectively in Australian men’s cricket at the state and national levels over 11 seasons (concluding in season 2008–09). In the last four of these seasons, there was more cricket played, with most of the growth being a new form of the game – Twenty20 cricket. Since the introduction of a regular Twenty20 program, injury incidence rates in each form of cricket have been fairly steady. Because of the short match duration, Twenty20 cricket exhibits a high match injury incidence, expressed as injuries per 10,000 hours of play. Expressed as injuries per days of play, Twenty20 cricket injury rates compare more favorably to other forms of cricket. Domestic level Twenty20 cricket resulted in 145 injuries per 1000 days of play (compared to 219 injuries per 1000 days of domestic one day cricket, and 112 injuries per 1000 days of play in first class domestic cricket). It is therefore recommended that match injury incidence measures be expressed in units of injuries per 1000 days of play. Given the high numbers of injuries which are of gradual onset, seasonal injury incidence rates (which typically range from 15–20 injuries per team per defined ‘season’) are probably a superior incidence measure. Thigh and hamstring strains have become clearly the most common injury in the past two years (greater than four injuries per team per season), perhaps associated with the increased amount of Twenty20 cricket. Injury prevalence rates have risen in conjunction with an increase in the density of the cricket calendar. Annual injury prevalence rates (average proportion of players missing through injury) have exceeded 10% in the last three years, with the injury prevalence rates for fast bowlers exceeding 18%. As the amount of scheduled cricket is unlikely to be reduced in future years, teams may need to develop a squad rotation for fast bowlers, similar to pitching staff in baseball, to reduce the injury rates for fast bowlers. Consideration should be given to rule changes which may reduce the impact of injury. In particular, allowing the 12th man to play as a full substitute in first class cricket (and therefore take some of the bowling workload in the second innings) would probably reduce bowling injury prevalence in cricket.

Keywords: injury profile, cricket, sport, Twenty 20

Introduction

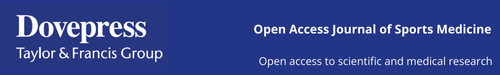

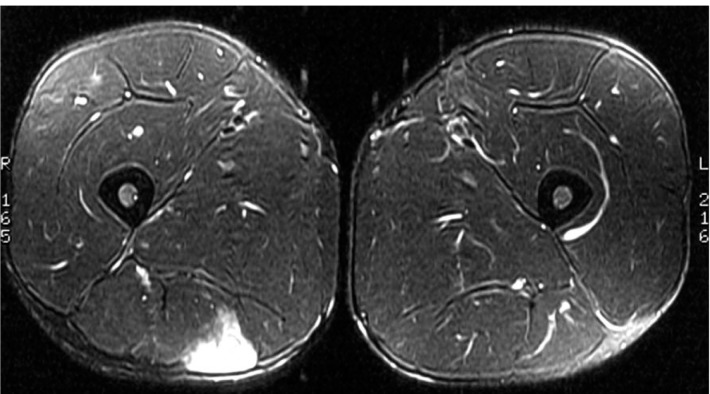

Cricket is one of the world’s major team sports in terms of regular international games. It is a bat-and-ball sport similar to the game of baseball, generally played outdoors on natural grass fields (Figure 1). Some of the major differences between cricket and baseball are that the ball is bowled (with a straight arm) in cricket, rather than thrown, and that the ball generally bounces on a pitch (Figures 2a and 2b) before it reaches the batter. The batting player is also not obliged to attempt to run if hitting the ball. Bowlers typically bowl in either of two styles, fast (with a long run-up, Figure 3a) or spin (with a shorter run-up, Figure 3b). Other than the newest form of cricket (Twenty20) in which teams are limited to facing 20 overs of six balls each, the length of the game in cricket is far longer than baseball and may in fact last for days. Despite being a game which may last for five days, cricket retains a tradition that the single substitute player for each 11-man team can only substitute as a fielder and is not allowed to bat or bowl.

Figure 1.

Aerial view of a cricket match, showing the bowler having just delivered (bowled) the ball; the two batsmen (striker and nonstriker); and some of the 11 players on the fielding team, including the wicketkeeper behind the stumps, who fields the ball if the batsmen does not hit it.

Figure 2.

A) A cricket pitch early in a match with visible grass blades and roots still seen. B) A cricket pitch later in a match. (Day four of a Test match) with no remaining grass on the pitch, but with wear and cracks visible due to deterioration over the previous days of play.

Figure 3.

A) Close-up of the delivery of a fast (or ‘pace’) bowler, who runs in at high speed to try to bowl at maximum speed. The bowler in this figure is wearing the colored uniforms of ‘limited overs’ cricket. B) The delivery of a spin bowler, who walks in to bowl off a few paces. Rather than attempting to beat the batsman with pace, the spin bowler attempts to have the ball move suddenly when it bounces on the pitch. The players in this photo are wearing the traditional white uniforms of test cricket.

At social levels, cricket produces relatively few injuries,1 but at elite levels injuries are quite common primarily due to higher intensity of matches and workloads.2–5 It is accepted by most researchers that ongoing injury surveillance is the fundamental pillar of successful injury prevention.6,7 Cricket Australia has published annual injury reports for the past decade in keeping with the first stage of injury prevention –regular ongoing surveillance.2,8,9

Cricket researchers published the first ever consensus international injury definitions for a sport in 2005,10–13 an innovation that was soon followed by football (soccer),14 and rugby union.15 However, in the five years since the cricket definitions were published, the landscape for professional-level cricket has changed dramatically. Most of the change has been due to the emergence of Twenty20 cricket, which was a fledging variety of the sport that was almost not taken seriously in 2005. In terms of crowd numbers, it has become the most popular form of the game in a very short time. The major changes this has had on the cricket calendar include the following:

That there is an absolute increase in the amount of cricket being played by teams at professional level. Although Twenty20 competitions have rapidly emerged, there has been no concurrent reduction in the amount of first class or 50-over one day cricket being played in most countries. Effectively the workload of most teams (and hence players) has increased in line with the amount of new Twenty20 cricket being played.

That for bowlers, as well as an increase in total workload per annum, there has been an increase in the variability of workload. A bowler playing in a Twenty20 competition would only be required to bowl four overs under match conditions every two-to-three days. Shortly after playing in such a competition, he might be required to play in a Test match and be expected to bowl 20 or more overs in a day. This rapid (up to fivefold) sudden increase in workload would be the equivalent of a runner suddenly moving from racing at 1500 m to competition in a half-marathon. The implications for increased injury risk are fairly stark.

That because of the outstanding popularity of domestic Twenty20 competitions which allow short-term player contracts, such as the Indian Premier League (IPL), players are now able to compete for multiple teams annually. This is a barrier to injury surveillance in that a nationally-based injury surveillance system may not have access to a player’s injury history during the time that he is under contract in another competition internationally. This increases the imperative to try to establish international injury surveillance in cricket.

The cricket definitions agreed upon in 2005 varied from the subsequent soccer and rugby definitions in that a cricket injury required the player to miss playing time in order to be included in surveillance. This would mean that fewer injuries were included in surveillance but in theory the definitions should be easier to comply with.16,17 In the consensus group there was some argument that the cricket definitions should attempt to record every condition which presented to medical or physiotherapy staff, which was the attitude taken by the consensus definition groups for the football codes. The eventual decision for cricket was made because of the anticipated difficulty with compliance in the sport of cricket (and given that some cricket-playing nations do not have advanced sports medicine services). Despite attempts to make the definitions easy to comply with, cricket injury surveillance has been very slow to evolve. There is still no international injury surveillance system in cricket and it appears that injury surveillance has been a low priority to date for bodies like the International Cricket Council (ICC) and the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), which organizes the IPL.

Bowling workload as a risk factor for overuse injury in cricket has been previously analyzed.18–20 Acute high one-off workloads20 and overs or sessions per week18,19 have both been associated with increased risk of bowling injury.

The purposes of this study were to update the injury profile of Australian first class cricket since the publication of the consensus definitions and to recommend slight changes to definitions based on the findings and changes to the cricket calendar in recent years.

Methods

Cricket Australia conducts an annual ongoing injury survey recording injuries in contracted first class players. Methods for this survey have been described previously2,9,10,12

The recommended methods of injury surveillance internationally were published in detail in 2005.10–13

The definition of a cricket injury (or ‘significant’ injury for surveillance purposes) is any injury or other medical condition that either:

prevents a player from being fully available for selection in a major match; or

during a major match, causes a player to be unable to bat, bowl or keep wicket when required by either the rules or the team’s captain.

The major injury rates presented are injury incidence and injury prevalence:

Injury incidence analyzes the number of injuries occurring over a given time period.

Injury match incidence considers only those injuries occurring during major matches.

Injury seasonal incidence considers the number of defined injuries occurring per squad per season. This can take into account gradual onset injuries, training injuries and match injuries in the one measurement. A ‘squad’ is defined as 25 players and a ‘season’ is defined as 60 days of scheduled match play.

Injury prevalence considers the average number of squad members not available for selection through injury for each match divided by the total number of squad members. Injury prevalence is expressed as a percentage, representing the percentage of players missing through injury on average for that team for the season in question. It is calculated using the numerator of ‘missed player games’, with a denominator of number of games multiplied by squad members. Player movement monitoring essentially requires that all players are defined in each match as either: (1) playing cricket, (2) not playing cricket due to injury or illness, (3) not playing cricket for another reason (eg, nonselection with no lower grade game available).

This report covers injuries from the cricket seasons shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dates of seasons covered by this survey

| Year | Season | Dates (according to May–April cricket ‘year’) |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 2008–09 | September 2008–April 2009 |

| 10 | 2007–08 | September 2007–March 2008 |

| 9 | 2006–07 | September 2006–April 2007 |

| 8 | 2005–06 | June 2005–April 2006 |

| 7 | 2004–05 | May 2004–March 2005 |

| 6 | 2003–04 | July 2003–March 2004 |

| 5 | 2002–03 | June 2002–April 2003 |

| 4 | 2001–02 | June 2001–April 2002 |

| 3 | 2000–01 | August 2000–April 2001 |

| 2 | 1999–00 | May 1999–April 2000 |

| 1 | 1998–99 | October 1998–April 1999 |

In order to promote consistency, the starting date for the Australian cricket year has been designated as the start of whichever series commenced after May 1 for every season under consideration (Table 1). The finishing date has been at the end of the latest finishing series which started in April each year. This definition has changed since our previous publication2 in order to promote consistency with other cricket authorities who are generally using May 1 (rather than April 1 which we have previously used) to designate the changeover of seasons. This date also better reflects the issuing of new annual contracts, which is typically done in June. This has affected the series commencing in April 2000 and April 2003 respectively which have now been included in the former years (1999–2000 and 2002–2003 respectively).

The recorders of injuries have been the team doctors and/or physiotherapists for the six states and the Australian team. Recorders have been encouraged to enter most injuries that have presented to medical staff into a database but to notify which ones qualified according to the survey definition (and by which criteria). The injury survey coordinator has kept records of all matches played by squad members (in a spreadsheet) and ensured that each state provided an explanation to the survey whenever one of their players was not selected, in order to keep the spreadsheet data accurate. Insurance forms completed by medical officers have also been cross-checked to ensure all insurance information was also entered as part of the survey. Media and Website reports have been regularly checked by the injury survey coordinator as a way of prompting injury recorders to provide a diagnosis.

Some of the injury rates reported here for seasons prior to 2008–09 may vary slightly from those published in previous reports. If input errors were found or definitions of injury categories have been changed then the updated values for previous seasons are included in this report. Therefore this report reflects the most accurate data from past seasons and the values presented here supersede all previous publications.

In accordance with the recommended international formula,10–13 hours of player exposure in matches is calculated by multiplying the number of team days of exposure by 6.5 for the average number of players on the field and then multiplying by the number of designated hours in a day’s play. For first class matches this is six hours per day, for one day matches this is 6.667 hours per day and for Twenty20 matches 2.7 hours per day. This gives a designated exposure in terms of player hours which is used as the denominator for match incidence calculations. Player days per team per season are calculated by multiplying the size of the squads (for each match) by the number of days for matches. A very minor variation from the international definition recommendations was that an uncontracted player was considered in season 2005–06 to have become part of the squad if he was selected as the 12th man in the team. This change was made in response to the rule in one day cricket for that season which allowed the 12th man to actively play as a substitute, a rule which was only used for this one particular season.

The definition of a ‘bowler’ according to the consensus statement was a player who bowled an average of five overs per match or more in the previous season. This definition requires alteration as there are now specialist Twenty20 bowlers who can only bowl a maximum of four overs per match. Nevertheless, in other circumstances it is still quite easy to classify regular bowlers and nonbowlers (batsmen or wicketkeepers) according to this definition and use the definition to adjudicate in the case of part-time bowlers as to whether they are classified as bowlers or not.

The methods used for Cricket Australia injury surveillance conform to the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and the latest National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines for research. They have been approved by the Cricket Australia Sport Science Sport Medicine Advisory Group as the relevant institutional review board. As injury surveillance is noninterventional and the methods preserve confidentiality of the players, it is characterized as ‘low or negligible risk’. Statement available at: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/e72-jul09.pdf (December 3, 2009).

Results

Injury exposure calculations

Table 2 lists the number of players in each squad per season, whilst Table 3 lists the number of matches per team per season. Since 1998–99 the Australian team has contracted 25 players annually prior to the start of any winter tours. The Australian squad for each subsequent season has been greater than 25 players, as it includes (from the date of their first match until the new round of contracts) any other player who tours with or plays in the Australian team. State teams can contract up to 20 other players on regular contracts (outside their Australian contracted players) and up to five players on ‘rookie’ contracts. As with the Australian team, any other player who plays with the team in a major match during the season is designated as a squad member from that time on. To date, players who have been contracted to play Twenty20 matches only for a state have been included as regular players according to the international definition. However, this is likely to be reviewed for the 2009–10 season as there is an increasing trend to sign players for the Twenty20 competition only.

Table 2.

Squad numbers per season

| Squad | 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 31 | 30 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 31 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 28 | 40 |

| New South Wales | 30 | 32 | 30 | 35 | 31 | 28 | 27 | 37 | 40 | 35 | 38 |

| Queensland | 20 | 23 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 33 |

| South Australia | 31 | 23 | 23 | 27 | 32 | 22 | 30 | 26 | 27 | 30 | 29 |

| Tasmania | 21 | 20 | 27 | 28 | 26 | 24 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 29 | 27 |

| Victoria | 26 | 23 | 27 | 31 | 30 | 29 | 26 | 36 | 31 | 25 | 26 |

| Western Australia | 23 | 26 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 37 | 34 | 32 | 34 |

Table 3.

Team matches under survey from 1998–99 to 2008–09

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 14 | 26 | 32 | 35 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 42 | 42 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 |

| Domestic first class | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 |

| International Twenty20 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 6 | ||||||

| One day international | 23 | 37 | 19 | 22 | 39 | 25 | 26 | 35 | 36 | 20 | 23 |

| Test match | 12 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 17 | 5 | 6 | 15 |

| All matches | 139 | 154 | 151 | 160 | 175 | 160 | 165 | 193 | 192 | 193 | 203 |

Table 3 shows that the number of matches under survey reached its highest level ever in season 2008–09. The format of the domestic first class competition (Sheffield Shield) since 1998–99 has consistently been that each of six teams plays 10 matches each, one home and one away against each of the other teams (60 team matches), followed by a final (two team matches) at the end of the season. The matches are all scheduled for four days, with the final being scheduled for five days. Since 2000–01, the domestic limited overs (one day) competition has followed the same ‘home and away’ format as the Sheffield Shield. The domestic Twenty20 competition (currently KFC Big Bash) commenced in season 2005–06 as a limited round of matches but has been expanded in each subsequent season. Season 2009–10 will include a further expansion to the calendar as Champions League Twenty20 matches will be included for two Australian teams each year. As seen from Table 4, in limited overs matches, the number of team days is generally the same as the number of team matches scheduled, with the exception of washed out games which count as zero days of exposure. Tables 3 and 4 show that the absolute amount of cricket being played each year is gradually increasing.

Table 4.

Team days played under survey 1998–99 to 2008–09

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 14 | 24 | 30 | 35 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 42 | 40 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 60 | 62 | 60 | 62 |

| First class domestic | 222 | 232 | 228 | 228 | 220 | 242 | 234 | 228 | 232 | 236 | 234 |

| International Twenty20 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 6 | ||||||

| One day international | 23 | 37 | 19 | 21 | 39 | 25 | 24 | 35 | 36 | 20 | 23 |

| Test cricket | 53 | 53 | 33 | 61 | 51 | 50 | 58 | 78 | 22 | 28 | 72 |

| Total | 340 | 362 | 342 | 372 | 372 | 379 | 377 | 418 | 377 | 385 | 432 |

Designated exposure in terms of player hours is expressed in Table 5 and used as the denominator for match incidence calculations. Overall exposure (in terms of match hours and overs bowled) has generally risen over the period of the survey, with the highest level of workloads in terms of days played, overs bowled and player hours of exposure being recorded in season 2008–09. The international calendar is undergoing changes due to the ever increasing number of Twenty20 tournaments. As has been previously discussed, increased match exposure tends to increase injury prevalence, as when matches are scheduled closer together there is less recovery time between games.

Table 5.

Designated player hours of exposure in matches each season

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 242 | 415 | 519 | 588 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 1819 | 1732 | 2685 | 2685 | 2685 | 2685 | 2598 | 2598 | 2685 | 2598 | 2685 |

| First class domestic | 8658 | 9048 | 8892 | 8892 | 8580 | 9438 | 9126 | 8892 | 9048 | 9204 | 9126 |

| International Twenty20 | 17 | 52 | 17 | 156 | 104 | ||||||

| One day international | 996 | 1602 | 823 | 909 | 1689 | 1082 | 1039 | 1515 | 1559 | 866 | 996 |

| Test cricket | 2067 | 2067 | 1287 | 2379 | 1989 | 1950 | 2262 | 3042 | 858 | 1092 | 2808 |

| Total | 13539 | 14449 | 13686 | 14865 | 14942 | 15155 | 15042 | 16342 | 14582 | 14435 | 16306 |

Table 6 shows that workload in terms of number of overs bowled has stayed fairly steady in first class domestic cricket over the past 10 years, but has increased in domestic one day cricket since 2000–01. The overall number of overs bowled reached an all time high in season 2008–09. Twenty20 cricket will probably not contribute substantially to overall bowling workload despite the new fixtures being introduced, although the number of days of cricket played will increase.

Table 6.

Overs bowled in matches each season

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 241 | 470 | 570 | 659 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 1874 | 1858 | 2690 | 2835 | 2697 | 2883 | 2729 | 2751 | 2877 | 2606 | 2751 |

| First class domestic | 9945 | 9729 | 9837 | 9833 | 9224 | 10311 | 9871 | 9645 | 9967 | 9713 | 9974 |

| International Twenty20 | 20 | 58 | 20 | 171 | 121 | ||||||

| One day international | 1061 | 1632 | 906 | 980 | 1700 | 1094 | 1057 | 1577 | 1488 | 805 | 959 |

| Test cricket | 1910 | 1882 | 1347 | 2243 | 2073 | 2000 | 2159 | 2756 | 890 | 1136 | 2833 |

| Total | 14791 | 15101 | 14780 | 15891 | 15694 | 16288 | 15835 | 17027 | 15711 | 15001 | 17299 |

Player days per team per season are calculated by multiplying the size of the squads (for each match) by the number of days for matches (Table 7).

Table 7.

Player days of exposure available (for prevalence calculations)1

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 441 | 739 | 887 | 1021 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 990 | 916 | 1495 | 1739 | 1675 | 1651 | 1564 | 1842 | 1911 | 1755 | 1843 |

| First class domestic | 5160 | 5343 | 5586 | 6435 | 5936 | 6477 | 6157 | 7193 | 7265 | 6981 | 7008 |

| International Twenty20 | 27 | 82 | 27 | 227 | 199 | ||||||

| One day international | 678 | 1051 | 544 | 608 | 1061 | 685 | 640 | 960 | 1056 | 536 | 743 |

| Test cricket | 1517 | 1444 | 947 | 1707 | 1352 | 1374 | 1562 | 2095 | 572 | 736 | 2169 |

| Total | 8345 | 8754 | 8572 | 10489 | 10024 | 10187 | 9950 | 12613 | 11570 | 11122 | 12983 |

Notes:

Seasonal incidence calculations use almost identical exposure data except that for prevalence calculations, a player who joins the squad midseason is not considered to be exposed to missing his first game through injury. This is because an uncontracted player can only be considered to have joined a squad midseason by playing a game, hence he cannot miss this first game through injury.

Injury incidence

Injury incidence results are detailed in Tables 8–13. Injury match incidence is calculated in Table 8 using the total number of injuries (both new and recurrent) as the numerator and the number of player hours of exposure (Table 5) as the denominator.

Table 8.

Injury match incidence (new and recurrent injuries/10,000 player hours)

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 41.3 | 120.4 | 115.6 | 51.0 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 55.0 | 34.6 | 48.4 | 22.3 | 37.2 | 67.0 | 42.3 | 65.4 | 48.4 | 53.9 | 78.2 |

| First class domestic | 32.3 | 24.3 | 22.5 | 45.0 | 24.5 | 23.3 | 24.1 | 14.6 | 28.7 | 39.1 | 36.2 |

| International Twenty20 | 0.0* | 192.7 | 0.0* | 321.1 | 0.0* | ||||||

| One day international | 80.3 | 56.2 | 60.8 | 33.0 | 82.9 | 37.0 | 67.4 | 19.8 | 51.3 | 46.2 | 10.0 |

| Test cricket | 24.2 | 62.9 | 23.3 | 29.4 | 15.1 | 61.5 | 8.8 | 23.0 | 23.3 | 36.6 | 17.8 |

| All matches | 37.7 | 34.6 | 30.0 | 37.7 | 32.1 | 37.0 | 27.9 | 25.7 | 37.0 | 47.8 | 38.6 |

Note:

No match injuries reported in these seasons.

Table 13.

Injury: seasonal incidence by body area and injury type

| Injury type | 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractured facial bones | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Other head and facial injuries | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Neck injuries | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Shoulder tendon injuries | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Other shoulder injuries | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Arm/forearm fractures | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other elbow/arm injuries | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| Wrist and hand fractures | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| Other wrist/hand injuries | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| Side and abdominal strains | 1.6 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| Other trunk injuries | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Lumbar stress fractures | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Other lumbar injuries | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| Groin and hip injuries | 2.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Thigh and hamstring strains | 3.2 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 4.4 | 4.8 |

| Buttock and other thigh injuries | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Knee cartilage injuries | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Other knee injuries | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Shin and foot stress fractures | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Ankle and foot sprains | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Other shin, foot and ankle injuries | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Heat related illness | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Medical illness | 0.7 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| Total | 18.0 | 16.4 | 17.4 | 18.3 | 19.8 | 16.4 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 16.8 |

Injury match incidence in the units of injuries per 10,000 player hours is higher in one day matches than first class matches and higher still in Twenty20 cricket. Because first class matches are played over a much longer duration than limited overs matches (at both domestic and international level), they produce a higher number of injuries per match, even though the hourly rate is lower.

Although match injury incidence is a useful unit of measure, many cricket injuries occur with a gradual onset and hence in Tables 8 and 9 there are some years in which there were a small number of international matches of a certain type and the match onset incidence was actually zero. Match play was still potentially contributing to the development of injuries, but because the injuries were of gradual onset they were not designated as match onset injuries.

Table 9.

Bowling match incidence (new and recurrent match injuries/1,000 overs bowled)

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 4.0 |

| First class domestic | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| International Twenty20 | 0.0* | 0.0* | 0.0* | 5.8 | 0.0* | ||||||

| One day international | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.0* | 1.8 | 0.0* | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.0* | 0.0* |

| Test cricket | 1.0 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 0.0* | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.0* | 0.7 |

| All matches | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

Note:

No match injuries while bowling reported in these seasons.

Table 10 analyzes match injury incidence by a new unit, injuries per 1,000 days of play. This unit was not recommended by the international definitions but enables a more direct comparison between Twenty20 cricket and the other forms. From this, it can be seen that Domestic Twenty20 matches have a lower bowling injury incidence than other forms of domestic cricket in terms of injuries per day of play, even though the incidence is comparable in terms of injuries per 1,000 overs bowled. The International Twenty20 figures follow a similar trend although are not yet as accurate due to the small number of International Twenty20 matches that have been played to date.

Table 10.

Match incidence analysis by player days (combined seasons 1998–99 through 2008–09)

| Match type | Injury incidence (n/10,000 player hours) | Injury incidence (n/1,000 days of play) | Bowling injury incidence (n/1,000 overs bowled) | Bowling injury incidence (n/1,000 days of play) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic 20/20 | 85.0 | 145.6 | 1.5 | 29.1 |

| Domestic one day | 50.6 | 219.2 | 2.2 | 99.4 |

| First class domestic | 28.6 | 111.6 | 1.3 | 56.0 |

| International 20/20 | 173.4 | 272.7 | 2.6 | 45.5 |

| One day international | 50.5 | 218.5 | 1.2 | 53.0 |

| Test cricket | 28.9 | 112.7 | 1.4 | 53.7 |

| All matches | 35.0 | 137.6 | 1.5 | 61.4 |

Seasonal incidence (Table 11 and Table 13) is calculated by number of injuries multiplied by 1,500 (for a squad of 25 players over 60 days), divided by the number of player days of exposure (Table 7). This peaked in 2007–08 but otherwise has stayed fairly constant over the last decade. Although there were more injuries (in total) in 2008–09 compared to 1998–99, this was only in proportion to the number of games and number of contracted players.

Table 11.

Injury seasonal incidence by team (injuries/team/season)

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 17.7 | 16.2 | 17.1 | 15.5 | 29.3 | 14.0 | 14.8 | 16.2 | 26.2 | 25.0 | 15.8 |

| New South Wales | 14.2 | 11.7 | 16.3 | 18.5 | 10.2 | 18.8 | 5.8 | 8.9 | 15.0 | 9.2 | 17.2 |

| Queensland | 11.5 | 17.0 | 17.2 | 25.3 | 15.7 | 20.4 | 17.9 | 15.0 | 20.6 | 36.3 | 17.4 |

| South Australia | 24.3 | 13.5 | 23.1 | 17.6 | 19.0 | 18.8 | 9.7 | 17.3 | 12.7 | 17.5 | 21.5 |

| Tasmania | 17.7 | 13.9 | 18.4 | 16.9 | 20.5 | 13.2 | 19.7 | 21.7 | 14.8 | 11.6 | 11.1 |

| Victoria | 18.6 | 23.3 | 16.9 | 20.5 | 21.1 | 17.7 | 13.4 | 15.9 | 20.4 | 29.0 | 19.5 |

| Western Australia | 21.1 | 19.7 | 14.1 | 16.6 | 21.0 | 14.2 | 23.6 | 11.9 | 12.4 | 16.3 | 16.0 |

| All teams | 18.0 | 16.4 | 17.4 | 18.3 | 19.8 | 16.4 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 17.4 | 20.2 | 16.8 |

Table 12 reveals that the injury recurrence rates have increased over the past two seasons. This is most likely to relate to the increased density of the cricket calendar, with greater pressure to return due to a higher number of games being missed in a shorter time period. It also may represent artifact to some extent in that players are less likely to return via grade cricket than they would have in the past. Technically, a recurrence suffered playing a return match in grade cricket does not count as an actual recurrence according to the definitions as the player has not returned yet to ‘List A’ cricket.

Table 12.

Injury seasonal recurrence rates (recurrent injuries/all injuries)

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence rates | 8.9% | 7.4% | 6.9% | 8.5% | 7.3% | 10.0% | 3.0% | 7.1% | 8.9% | 17.3% | 15.8% |

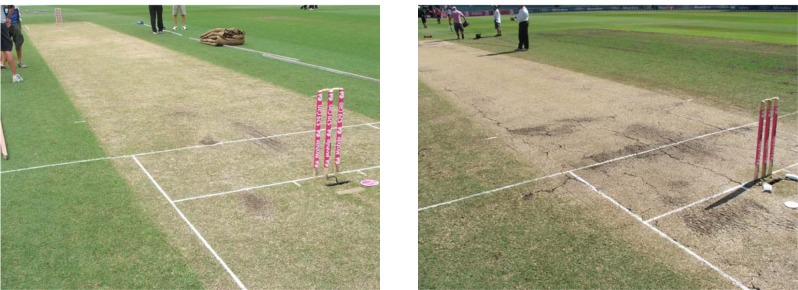

Table 13 reveals that seasonal incidence by body part has generally been consistent over the past 11 seasons. Some injury categories have fallen slightly in incidence in recent seasons including shoulder tendon injuries and wrist and hand fractures, although most categories have stayed fairly constant. Thigh and hamstring strain injury incidence has risen in recent seasons. Hamstring strains (Figure 4) are clearly the most common injuries (ie, most frequently occurring) in cricket. They occur in all forms of the game (batting, bowling, fielding, training and sometimes with gradual onset).

Figure 4.

Axial T2 magnetic resonance image showing a typical hamstring strain.

Injury prevalence

Injury prevalence rates follow a similar pattern to injury incidence, however, although incidence stayed constant over the past few seasons, prevalence has gradually increased. The disparity between the two can be attributed to the generally increased number of matches, with the ‘average’ injury artificially becoming more severe over recent years because there are more matches to miss (injury prevalence = injury incidence × average injury severity).

Injury prevalence rates (Tables 14–16) in season 2008–09 were slightly higher than the long-term average, which is an expected outcome given the steadily increasing amount of match exposure at domestic level. Pace bowlers remain the position most susceptible to missing time through injury (Table 15). In season 2008–09, 21% of fast bowlers were missing (on average) through injury at any given time. It continues to be a priority to research further the possible risk factors for pace bowlers in order to control their injury rates.

Table 14.

Injury prevalence by type of match

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Twenty20 | 10.9% | 10.0% | 12.1% | 12.4% | |||||||

| Domestic one day | 7.1% | 7.0% | 8.0% | 11.3% | 8.8% | 11.9% | 9.5% | 10.3% | 11.5% | 13.5% | 9.7% |

| First class domestic | 6.6% | 6.9% | 9.5% | 10.4% | 9.0% | 11.2% | 8.6% | 10.4% | 10.0% | 10.8% | 9.2% |

| International Twenty20 | 7.4% | 2.4% | 14.8% | 11.5% | 22.6% | ||||||

| One day international | 13.7% | 7.6% | 10.5% | 8.4% | 8.9% | 13.4% | 3.8% | 6.9% | 10.8% | 12.7% | 18.2% |

| Test cricket | 6.3% | 9.8% | 11.5% | 6.2% | 7.5% | 11.0% | 6.3% | 8.2% | 8.4% | 9.6% | 14.3% |

| All matches | 7.2% | 7.5% | 9.5% | 9.7% | 8.7% | 11.4% | 8.1% | 9.7% | 10.3% | 11.4% | 11.1% |

Table 16.

Comparison of injury prevalence by body area

| Body region | 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractured facial bones | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Other head and facial injuries | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Neck injuries | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Shoulder tendon injuries | 0.6% | 0.4% | 0.8% | 1.4% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Other shoulder injuries | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 1.1% | 0.2% |

| Arm/forearm fractures | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Other elbow/arm injuries | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Wrist and hand fractures | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.3% |

| Other wrist/hand injuries | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.6% | 0.1% |

| Side and abdominal strains | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 0.8% |

| Other trunk injuries | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Lumbar stress fractures | 0.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.1% | 0.2% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 0.8% | 0.8% |

| Other lumbar injuries | 0.7% | 1.3% | 0.9% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 1.3% |

| Groin and hip injuries | 1.1% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.6% | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.4% |

| Thigh and hamstring strains | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 1.1% | 1.6% | 2.3% |

| Buttock and other thigh injuries | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.4% |

| Knee cartilage injuries | 0.4% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Other knee injuries | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.4% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Shin and foot stress fractures | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 1.0% |

| Ankle and foot sprains | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 1.5% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 1.6% | 0.5% |

| Other shin, foot and ankle injuries | 0.1% | 1.1% | 0.1% | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.4% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.8% |

| Heat related illness | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Medical illness | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

| Total | 7.2% | 7.5% | 9.5% | 9.7% | 8.7% | 11.4% | 8.1% | 9.7% | 10.3% | 11.4% | 11.1% |

Table 15.

Injury prevalence by player position

| 1998–99 | 1999–00 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batsman | 3.9% | 3.5% | 5.2% | 4.7% | 3.9% | 6.7% | 9.8% | 6.3% | 5.5% | 7.7% | 6.4% |

| Wicketkeeper | 2.8% | 1.4% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.8% | 3.9% | 3.2% | 2.9% | 0.5% | 1.7% | 3.3% |

| Pace bowler | 11.5% | 14.1% | 15.0% | 19.4% | 16.5% | 18.2% | 9.3% | 14.4% | 18.6% | 19.1% | 20.7% |

| Spin bowler | 4.9% | 1.4% | 10.1% | 1.1% | 3.6% | 7.1% | 4.2% | 8.8% | 4.1% | 10.7% | 5.5% |

| Total | 7.2% | 7.5% | 9.5% | 9.7% | 8.7% | 11.4% | 8.1% | 9.7% | 10.3% | 11.4% | 11.1% |

Injury prevalence by injury category (Table 16) revealed no outstanding trends for recent seasons other than an increase in time missed due to thigh and hamstring strains. This may be related to an increased speed of movement in Twenty20 cricket.

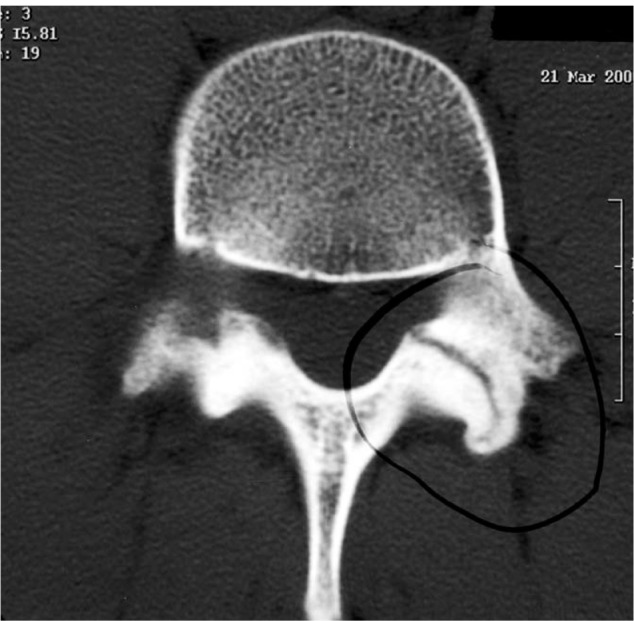

The injuries which are most common (have the highest seasonal incidence) are generally the most prevalent (ie, cause the highest number of missed games). The exceptions to this trend are lumbar injuries, particularly lumbar stress fractures (Figure 5). Lumbar stress fractures in bowlers generally cause many missed months of playing time and so they do not show a particularly high incidence (Table 13) but do show a high prevalence (Table 16).

Figure 5.

Axial computed tomography scan showing a typical pars interarticularis stress fracture.

Injury prevalence by player age and position

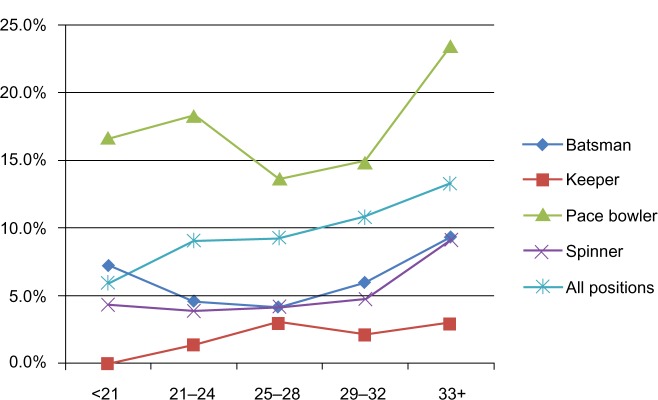

Table 17 and Figure 6 show that pace bowlers are easily the position most prone to missing time through injury and that increasing player age is a strong risk factor for injury. Batsmen, wicketkeepers and spin bowlers in general have a slowly increasing injury prevalence as they age. Fast bowlers have more of a J-shaped curve, where they are quite susceptible to injury at young ages (particularly lumbar stress fracture), their injury risk decreases through the mid-20s and then increases to be substantial once again in older bowlers over the age of 32.

Table 17.

Injury prevalence by player age and position (pooled data from 1998–99 to 2008–09)

| < 21 | 21–24 | 25–28 | 29–32 | 33+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batsman | 7.2% | 4.6% | 4.1% | 6.0% | 9.3% |

| Keeper | 0.0% | 1.4% | 2.9% | 2.1% | 2.9% |

| Pace Bowler | 16.7% | 18.3% | 13.7% | 14.9% | 23.5% |

| Spinner | 4.4% | 3.9% | 4.2% | 4.8% | 9.1% |

| Total | 6.0% | 9.1% | 9.3% | 10.9% | 13.3% |

Figure 6.

Injury prevalence by position and age group (pooled data from 1998–99 to 2008–09).

Discussion

Injury profile

The injury profile in this study is similar to that reported in previous studies of cricket injuries.2,5,9,21,22 The most common injury in the game is the hamstring strain. The incidence and prevalence of hamstring strains are both increasing, possibly due to the amount of cricket being played and possibly due to an increased risk associated with Twenty20 cricket. The most severe of the common injuries is the lumbar stress fracture in fast bowlers, which generally affect younger players more than older players, and which are usually season-ending. Apart from this injury which makes young fast bowlers quite prone to injury, older players are injured more often than younger players.

In general the number of cricket injuries has remained fairly steady over the past decade, if it is considered in proportion to the amount of cricket played (ie, seasonal incidence which is adjusted for length of season). The injury prevalence has been steadily increasing, primarily due to an increase in severity of injuries (average number of missed games per injury). Some of this is artificial, in that the more crowded calendar of matches will mean that a player with an injury which takes a month to recover will miss more games if there are more games scheduled per month, as has been the case in recent seasons.

Injury definitions

The injury definitions proposed by the international consensus statements10,12,13 are workable and generally can be used to undertake ongoing surveillance. There has been some comment that the proposed cricket definitions are too narrow and do not catch enough injuries.23,24 However, the lack of many published studies since the definitions were determined indicates that many countries still lack the resources to comply with the ‘simple’ definitions that were chosen with compliance in mind.16,17 It would be hard to argue that the definitions should be expanded to make capture more difficult given that injury surveillance appears to be under-resourced internationally.

The expansion of Twenty20 cricket in the past few years requires a reanalysis of the definitions used for the cricket injury surveillance. This should be done with international collaboration. Suggested changes include the following:

Cohort definition should allow players to be able to come in and out of the squad over the course of a single season. This is applicable to players who sign a Twenty20 contract only, for example in the IPL or Australian Big Bash competitions, which last for weeks rather than an entire year.

Match injury definition of units should probably be changed to include a unit injuries/1,000 player days (Table 10) rather than/10,000 player hours. This allows better comparison between the risk of Twenty20 cricket and other forms of the game. However, seasonal injury incidence should be used as the core unit for incidence given that overuse injuries are better captured this way25 and many injuries occur as a build-up of cumulative fatigue.20 Match workload data from a previous study confirmed that a match workload of >50 overs in a first class match (and, in particular, >30 overs in the second innings of the match) leads to an increased risk of bowling injury for pace bowlers.20 Interestingly this increased risk is most demonstrated for a delayed period of 21–28 days after the heavy workload (rather than immediately after). This artifact makes analysis of Twenty20 injury incidence somewhat problematic. As a high percentage of fast bowling injuries are ‘overuse’ in nature, an injury of this nature occurring in a Twenty20 may reflect cumulative overuse from previous first class cricket. Reports of injury rates in exclusively Twenty20 competitions (such as the IPL and Indian Cricket League) will be important to take note of, although again this data may be affected by cricket played in the lead up to these events.

Injury prevention

The increased scheduling in the cricket calendar at both domestic and international levels represents the highest challenge in terms of preventing injuries in the future. Although overuse is the main concern, underuse (ie, leading to sudden increases in load) may be a problem. Lack of acclimatization to high workloads may occur playing Twenty20 cricket and this may lead to an increased risk of injury on return to first class cricket from a spell in Twenty20 cricket.

Acute high overloads are very difficult to control in first class cricket. Overs bowled cannot necessarily be planned by the team’s captain or coach and are often at the mercy of how well the opponents are batting. Nevertheless there are some factors which perhaps could be considered. The most contentious would be allowing the 12th man to bowl if made as a permanent replacement. This suggestion has been discussed before, with the major objection being that the nature of the game would be significantly changed if a substitute was used for a minimally-injured or noninjured player. Although using the 12th man as a substitute has been trialed and actually discarded in limited-overs cricket, it has not previously been trialed in first class cricket. Obviously a potential place where it could be implemented on a trial basis, without requiring consent of all countries, is in the domestic competitions. Presumably many teams would often choose spin bowlers as their ‘12th man’ who could substitute in for a batsman or pace bowler during the second innings. This extra bowler would act as insurance against the original bowlers being over-bowled in the second innings of matches. Although associated with difficulties in implementation and a fight against tradition, the statistics support an increased risk of injury for bowling >50 overs in a match or >30 overs in the second innings for pace bowlers.20 In first class cricket, a strong argument can be made in particular that if a pace bowler breaks down early in a match that he should be able to be replaced, as the consequence of not doing so is the almost inevitable over-bowling of the remaining fit bowlers. Despite the tradition, it is worth remembering that cricket is a fairly unique team sport on the world stage in terms of not allowing injury substitutes – in a sport which has the longest duration of play! A further consideration is that the potential use of a fit bowling substitute may tilt the balance of the game back slightly in favor of the bowlers, given that recent changes in cricket have tended to favor batsmen. As a counter-argument, it may tilt the game further in favor of the team who bats first (and bowls last) as it would be of most advantage to substitute a bowler for the final (bowling) innings only.

Short of rule changes, the knowledge of which players are at higher risk for the following month from acute workloads can help team coaching and fitness staff better plan training workloads. A player who has an acute single overload (or even more so, if on more than one occasion) in the previous month can be tagged as ‘at risk’ and used more sparingly where the option is available, particularly at training.

It is likely that in the future teams will need to develop more of a ‘squad’ mentality towards their fast bowlers in a similar fashion to professional baseball teams’ attitude to their pitchers. In periods flagged as high risk for injury (playing after a high one-off workload or playing first class cricket after a break where only limited overs cricket was played), it may become necessary to rest fast bowlers to concentrate on conditioning in order to reduce the risk of further long-term injury.

All countries should be encouraged to undertake injury surveillance and distribute reports to other countries. It is acknowledged that injury surveillance is expensive and is very unlikely to be successful in the long-term without adequate ongoing funding. It is perhaps worth seeking international funding, either through the ICC or a major corporate sponsor, to assist with the payment for injury surveillance in the Test-playing countries where it is not currently being undertaken.

The priority areas for injury risk factor studies continue to be studies of fast bowlers, who have the highest injury prevalence.2,9 Workload and biomechanical technique studies26,27 have the greatest chance of being able to reduce the risk of fast bowling injury in the modern cricket calendar.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the recent contributions of the following practitioners, along with all of those acknowledged in previous Cricket Australia annual injury reports:

Team physiotherapists: Patrick Farhart, Murray Ryan (New South Wales), Adam Smith (Queensland), John Porter (South Australia), Michael Jamison (Tasmania), Rob Colling (Western Australia), Kevin Sims (Australia).

Team medical officers: Neville Blomeley (Queensland), Terry Farquharson (South Australia), David Humphries and Peter Sexton (Tasmania), Damien McCann (Western Australia).

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Accident Compensation Corporation Sport Claims ACC Injury Statistics 2006 1st edSection 20Wellington, NZ: ACC; 2006Available from http://www.acc.co.nz/about-acc/acc-injury-statistics-2006/SS_WIM2_062694Accessed on February 2, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orchard J, James T, Portus M. Injuries to elite male cricketers in Australia over a 10-year period. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(6):459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stretch RA, editor. First World Congress of Science and Medicine in Cricket. Shropshire: 1999. The incidence and nature of injuries to elite South African cricketers. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stretch R. Epidemiology of cricket injuries. Int SportMed J. 2001;2(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mansingh A, Harper L, Headley S, King-Mowatt J, Mansingh G. Injuries in West Indies cricket 2003–2004. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:119–123. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.019414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper H. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries: A review of concepts. Sports Med. 1992;14(2):82–99. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orchard J, James T, Kountouris A, Portus M. Cricket Australia Injury Report 2007. Sport Health. 2008;26(1):16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orchard J, James T, Alcott E, Carter S, Farhart P. Injuries in Australian cricket at first class level 1995/96 to 2000/01. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:270–275. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orchard J, et al. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(4):E22. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.012732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orchard J, et al. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. NZ J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):90–99. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.012732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orchard J, et al. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(05)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orchard J, et al. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. South African Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;17(2):18–28. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.012732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller C, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:193–201. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuller C, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures for studies of injuries in rugby union. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:328–331. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.033282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orchard J, et al. Defining a cricket injury [Letter to the Editor, rejoinder by authors] J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(3):358–359. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(05)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orchard J, Hoskins W. For debate: consensus injury definitions in team sports should focus on missed playing time. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):192–196. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3180547527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis R, Farhart P, Goumas C, Orchard J. Bowling workload and the risk of injury in elite cricket fast bowlers. J Sci Med Sport. 2003;6(3):359–367. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(03)80031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennis R, Finch C, Farhart P. Is bowling workload a risk factor for injury to Australian junior cricket fast bowlers? Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:843–846. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orchard J, James T, Portus M, Kountouris A, Dennis R. Fast bowlers in cricket demonstrate up to 3- to 4-week delay between high workloads and increased risk of injury. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(6):1186–1192. doi: 10.1177/0363546509332430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stretch R. Cricket injuries: a longitudinal study of the nature of injuries to South African cricketers. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:250–253. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.3.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stretch R. The incidence and nature of epidemiological injuries to elite South African cricket players. S Afr Med J. 2001;91(4):336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell R, Hayen A. Defining a cricket injury [Letter to the Editor] J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8(3):357–358. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(05)80047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hodgson L, Gissane C, Gabbett T, King D. For debate: consensus injury definitions in team sports should focus on encompassing all injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):188–191. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3180547513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahr R. No injuries, but plenty of pain? On the methodology for recording overuse symptoms in sports. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):966–972. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portus M, Mason B, Elliott B, Pfitzner M, Done R. Technique factors related to ball release speed and trunk injuries in high performance cricket fast bowlers. Sports Biomech. 2004;3(2):263–284. doi: 10.1080/14763140408522845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portus M, Galloway H, Elliott B, Lloyd D. Pathomechanics of lower back injuries in junior and senior fast bowlers: a prospective study. (Abstract) Sport Health. 2007;25(2):8–9. [Google Scholar]