Abstract

Background

Rapid urbanization and unplanned population development can be detrimental to the safety of citizens, with children being a particularly vulnerable social group. In this review, we assess childhood playground injuries and suggest safety mechanisms which could be incorporated into playground planning.

Methods

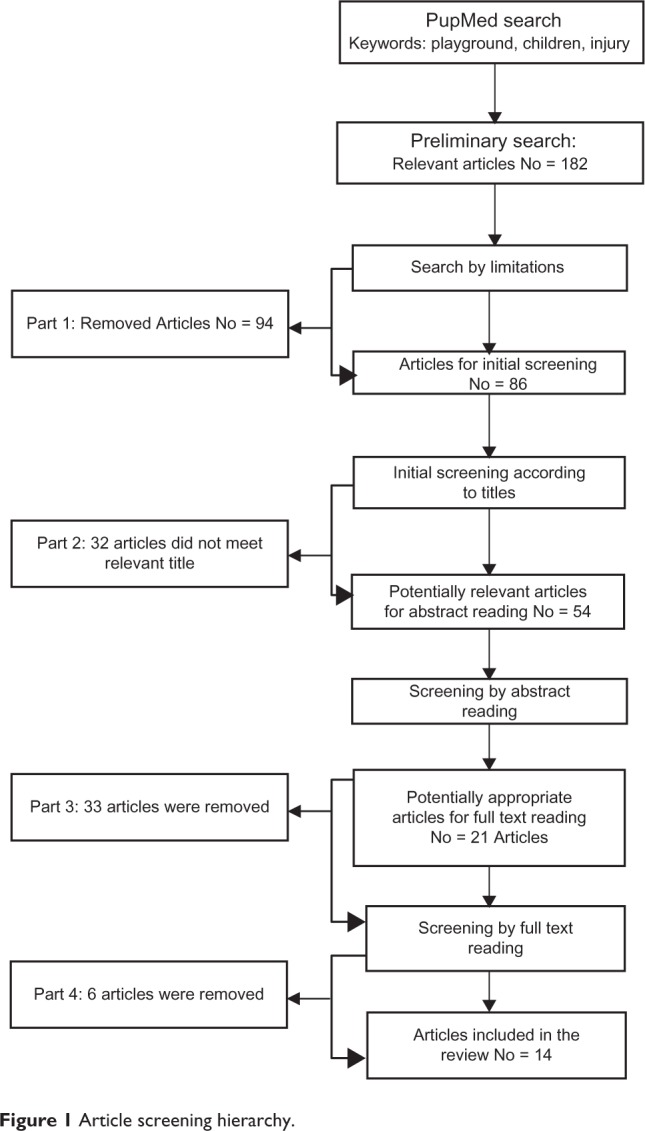

Inclusion criteria were “children” as the focus group, “playground” as the main field of study, and “unintentional injury” and “safety” as the concepts of study. The keywords used for the PubMed search were “playground”, “children”, and “injury”. Initially we 182 articles. After screening according to inclusion criteria, 86 articles were found, and after reading the abstracts and then the full text, 14 articles were finally included for analysis. The papers reviewed included four case-control studies, three case studies, three descriptive studies, two interventional studies, one retrospective study, one cross-sectional study, and one systematic review.

Results

Playground-related fractures were the most common accidents among children, underscoring the importance of safety promotion and injury prevention in playgrounds, lowrisk equipment and playing hours (week days associated with higher risk), implementation of standards, preventing falls and fall-related fractures, and addressing concerns of parents about unsafe neighborhoods. With the exception of one study, all of the reviewed papers had not implemented any practical safety plan. Safe engineering approaches were also ignored.

Conclusion

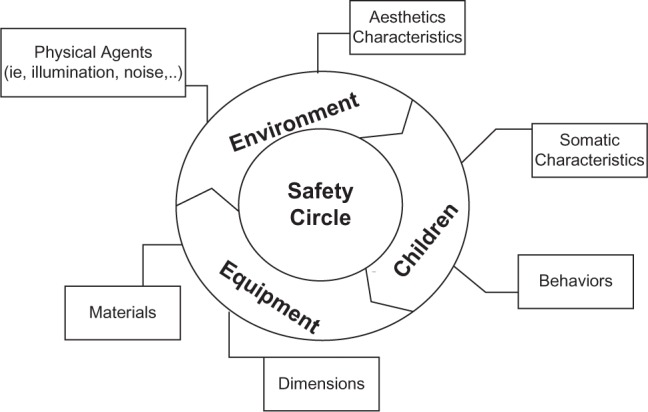

We recommend a systematic safety approach based on the “safety circle” which includes three main areas, ie, equipment, environment, and children.

Keywords: children, playground, injury, safety

Introduction

Health and safety problems are increasing with rapid urbanization and increasing population pressure in major cities. Studies in many industrialized countries show that public health is affected by increasing populations, and safety-related problems threaten all age groups.1 Rapid urbanization and unplanned increases in population elevate the risks for children in developing countries.2 According to global reports, around 51.5% of the world’s population, representing an estimated number of 7 billion people, are now living in cities.3,4 Undoubtedly, accidents occur in high population areas more often than in low population areas. Similarly, playground injuries in crowded neighborhoods are more likely to occur and with more serious consequences than in a neighborhood with a low ratio of population to accessible land area. Therefore, the safety of urban-dwelling children should be one of our most important global concerns. Child-oriented safety promotion programs focusing on sustainable and safe neighborhoods play a significant role in creating safer cities and a better constructed environment. Healthy cities require safe playgrounds, given that children spend a lot of time in these facilities.6,7

Play is an integral part of childhood development,8–10 and is a powerful resource for acquisition of cognitive, psychosocial, and physical skills, so access to safe play spaces is essential.6,11–17 Playgrounds can make a significant contribution to social, emotional, and intellectual development during childhood,6 but with a high probability of childhood injuries.7,14,18 For example, in the US, nearly 211,000 children per year are treated in emergency rooms for playground-related injuries.7

Each year, 10–30 million children and adolescents sustain an injury, and approximately 950,000 children die every year due to accidental injuries or violence.19 A few years ago, some international groups and organizations addressed these problems and made voluntary standards for playgrounds (eg, ASTM F1487). In addition, new guidelines by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission have been developed for the prevention of injuries in children during play.20

Tens of millions of children require hospital care every year for nonfatal injuries, including those sustained in playgrounds.2,21 Several studies of injuries associated with playground equipment have been reported from around the world, but none has used large global databases to evaluate the types of injury in detail.8 The “World Report on Child Injury Prevention” has advocated global attention to reduce childhood injuries using a range of strategies, including playground safety and safeguards against injury.2,7,22,23

The available evidence indicates that Sweden was the first country to appreciate the scope and significance of children’s health and injuries. Around six decades ago, the rate of childhood death in Sweden was higher than that in the US, but after the 1980s, because of forward planning, Sweden now has the lowest rates of child injury.23 An observational study from Wales showed that 90% of playground-related accidents requiring emergency room attendance were attributable to unsafe playground equipment.16,22 Previous research has also indicated that playground swings are the most common cause of traumatic brain injuries in children.8,10 In Canada, 28,500 children per year are treated in hospital for injuries related to falls in playgrounds.14

Falls from playground equipment are one of the most important causes of childhood injuries.11,13,15,21,24–27 Reports show that the majority of injuries in children aged younger than 13 years are related to school playground and equipment.15,23 In Ontario, falls from playground equipment are the second commonest cause of hospitalization as a result of sporting and recreational activities.14

This review assesses childhood playground injuries and addresses potential safety mechanisms by making some practical recommendations for childhood injury prevention in playgrounds.

Methods

In this research, we focused on physical safety and accidental events causing bodily injury to children during their activities in playgrounds. Neighborhood safety is a prominent issue for children, because outdoor safety encourages parents to allow their children to play in playgrounds.28 We reviewed the literature on playground injury and children’s safety using PubMed. Keywords were “playground”, “children”, and “injury”. We initially identified 182 relevant papers, without any limitations in the search. Eighty-six articles were found using the following limitations: “English language”, “human”, “age group under 18 years”, and “last 10 years”. Inclusion criteria were: children as a focus group; playground as the main field of study; and unintentional injury and safety as the concepts of the study. Exclusion criteria were: not involving playground injuries; cost–beneft injury studies; and specific groups, such as athletes. Likewise, editorials and articles discussing treatment of childhood injuries were excluded. On initial screening, 32 articles were excluded. We then critically reviewed 54 abstracts and excluded a further 33 papers. Full texts of the 21 remaining articles were accessed. Finally, 14 articles were included in our study. The whole screening and acceptance process is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Article screening hierarchy.

Because playground injuries are complex phenomena and include environmental factors, characteristics of children, and related equipment, we categorized the papers under three main headings, ie, equipment, environment, and children.6,29

Results

The 14 papers included in this review comprised four case-control studies, three case studies, three descriptive studies, and two interventional studies, and one retrospective, cross-sectional, and systematic study each. The main findings of these papers are discussed in this section. Table 1 reports how long ago the studies were carried out, and Table 2 summarizes the methods and main findings of these studies.

Table 1.

Published relevant papers identified in the PubMed data base, according to year and location of study

| Publication date | Total (n) | Selected papers (n) | Place of study (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 years ago | 86 | 15 | Austria (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), Colombia (n = 1), Singapore (n = 2), US (n = 4), worldwide (n = 1) |

| 5 years ago | 44 | 10 | Austria (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), Singapore (n = 2), US (n = 3), worldwide (n = 1) |

| 3 years ago | 27 | 5 | Austria (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), US (n = 2), worldwide (n = 1) |

| 2 years ago | 17 | 2 | Austria (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1) US (n = 2) |

| Last year | 8 | 1 | US (n = 2) |

Table 2.

Review of the selected articles from PubMed

| Reference | Location | Methods | Main findings | Conclusions | Approach*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eq. | Env | Ch | |||||

| Fiissel14 | Toronto Canada |

Case-control study Data-gathering based on pediatric records at Toronto Hospital 1995–2002 Study of playground falls and related fractures according to gathered data Cases included those who fell from a height in playgrounds; controls were those who fell from a standing height Study of minor and major fractures |

Likelihood of equipment falls and related fractures were 3.91 times more than fractures resulting from standing height falls No significance difference found between two types of falls 48% (n = 3155) of all cases treated at the hospital had fractures, 1070 of which were detected as playground fall-related fractures More than 85% of fractures were of the upper extremities |

Falls from playground equipment known to be a prominent cause of childhood fractures Prevention of play-related fractures among children should be defined as one of the main goals of safety promotion in playgrounds |

* | ||

| Heck et al18 | Columbia | Interventional study, a multiple baseline design, across three classrooms (5379 children) Recording of child behavior during play (especially for slides and climbers) 5-day safety training course for children |

Obvious changes in children’s behavior recognized during slide playing Among second graders who had lower intervention, higher baseline rates detected |

Children’s play behavior affected by presence of observers, but year-long supervision impractical Duration of intervention and supervision important |

* | * | |

| Howard16 | Ontario Canada |

Interventional study changing unsafe to safe play. Study of injuries before and after intervention in 86 schools | Decreasing rate of injury in intervention schools was 0.93 injuries/1000 students/month | One of the safety promotion approaches might be replacing safe equipment | * | ||

| Lafores30 | Montreal Canada |

Case-control study in 102 selected playgrounds Field observation in summers of 1991–1995 Assessment of playground surface materials Interview of 1286 parents by telephone questionnaire |

35% of falls occurred on surfaces with high-risk injury according to g level Occurrence of injuries during play with equipment 2 m in height occurred 2.56 times more often than 1.5 m ones Surface material and height of equipment have some relationship with risk of injury; surface resilience can be a predictor of risk severity |

Selection of playground surfaces should consider material resilience when planning safety promotion in playgrounds | * | ||

| Mahadev31 | Singapore | Retrospective study of play-related fractures in 390 patient records in a children’s hospital during May 1997–December 1998 Samples categorized into 4 age groups (<2, 2–5, 5–12, and 12–15 years) |

19.5% total treated fractures (n = 2001) were related to playgrounds Fractures in boys were twice as common as in girls; 68% of cases were Chinese, 17% Malay, 11% Indian, and 4% others Most fractures (70.7%) occurred in children aged 5–12 years Most of fractures occurred during play with monkey bars and other upper body devices. |

Playground surface materials and monkey bar height need evaluation | * | ||

| Mitchell33 | New South Wales Australia | Descriptive study of hospitalization data (1992/93 to 2003/04) of children (aged ≤ 14 years) who had suffered injuries related to a fall from playground equipment | Rate of 106.6/100,000 children for injuries related to falls Statistical analysis showed increased trend of injuries from 83.3 to 130.3 per 100,000 children, highest in 5–9-year-old boys (198.4/100,000 children) |

Decreasing incidence of head injuries, but increasing upper extremity injuries, so safety auditing and risk assessment needed Playground safety standards have an important role in injury prevention |

* | ||

| Upper extremity injuries and fractures recorded as common injuries for all age groups , with an upward trend; head injury rate decreased | Better implementation of safety standards necessary | ||||||

| Nixon9 | Brisbane Australia |

Case study of playground equipment-related injuries in children Assessment of emergency data from 2 hospitals over 2 years focusing on children Random sampling and selection of 16 playgrounds and one hour observation in each sample during spring, winter, and autumn |

Numbers of times equipment used in playgrounds sampled were 3762, 2309, and 825 for climbing, horizontal ladders, and slides, respectively Frequency of use was different between schools and park playgrounds Injury rate for school playgrounds was 59/100,000 per year and 0.26/100,000 per year for park playgrounds |

Distribution of equipment was not obvious between school and park playgrounds; comparison of equipment within the samples was not possible; however, the overall rate of injuries was low Intervention could reduce this low injury rate further |

* | ||

| Olsen17 | Iowa USA | Case study and comprehensive survey Description of significance of plan for injury prevention in school playgrounds Using of a safety model as a basic plan for development of injury prevention in schools |

Effectiveness of a safety model for children’s safety; health care experts and elementary schools should be aware about school supervisory approaches for injury cost reduction Appropriately trained school nurses are essential for playground safety promotion in schools |

Understanding of importance of safety should be communicated in addition to playground safety training School playground safety involves a system for proper safety supervision |

* | * | |

| Powell et al20 | Chicago, IL | Description of hazards in 78 playgrounds including 42 cases in low-income neighborhoods and 26 cases in very low-income neighborhoods | Some playground equipment had problems regarding adequate surrounding space Inadequate space around 30% of swings, 83% of ladders, 69% of sliding poles, 54% of cargo nets, 49% of spiral climbers, 46% of arch climbers, 40% of chinning bars, and also 50% of slides with a height more than 4 feet Comparison between playgrounds in low-income and very low-income neighborhoods showed that playground hazards were similar |

Improving playground safety needs planned endeavors Effective maintenance should be implemented in all playgrounds Inadequate spaces around equipment should be checked and improved Local residents should be encouraged to clean and remove trash, broken equipment and debris, involves local and neighborhood municipal bodies |

* | ||

| Schwebel et al34 | USA | Case study of 49 girls and 51 boys, mostly Caucasian, who attended in a laboratory for motor ability tests, measured by balancing block on head, balance beam walking, bead stringing Unintentional injury questionnaire filled out by mothers |

Rate of injuries in boys higher during laboratory-based tests. Age and gender differences were not significant No correlation between motor ability and injury risk Motor ability had a high correlation with diary-recorded injuries |

No relationship between somatic abilities and injury, findings might be useful for playground equipment and toy manufacturers | * | * | |

| Sherker15 | Melbourne Australia | Validated methods of biomechanics and epidemiology Development of a case-control study Development of a designed dummy for simulation of accidental falls Main focus group was children aged < 13 years who suffered a play-related fracture 5 hospitals selected for study |

Most costly group of playground-related problems were upper extremity fractures | Potential bias towards more serious falls among controls To assist with compliance, upon completion of the schools’ commitment to the study, free playground surface materials were provided to control schools |

* | ||

| Sherker32 | Victoria Australia, |

Unmatched case-control study in 5 hospitals and 78 randomly selected control schools, data gathered October 2000–December 2002 Cases were 402 children (< 13 years) who had fallen while playing in school playgrounds and suffered an arm fracture. Controls (n = 283) had no or minor injuries. Children were interviewed in the playground regarding interventions. Measurement of playground equipment dimensions | Risk of upper arm fracture greatest for equipment heights > 1.5 m and for fall heights > 1.0 m Depth beneath equipment not enough for accident prevention |

Recommendations for playground surfaces should be revised Equipment height needs revision to a safe level with maximum 1.5 m for height |

* | * | |

| Tan et al6 | Singapore | Cross-sectional descriptive study and assessment of data documented during February 2002–January 2004 in emergency departments of three hospitals Assessment of recorded data for 19,094 injured children < 16 years |

1617 of 19,094 recorded injuries were playground-related Falls were the most common injury (70.7%), but most (99.4%) were minor; around 37% occurred at 1800–2100 hours, and 27.6% at 1500–1800 hours. Incidence rates were different between weekdays, and also for months Most were upper extremity fractures and occurred in children aged 6–10 years | Falls from monkey bars were the most common injuries and occurred during weekends and vacation months, ie, June and December, so interventional planning needed Redesigning of playground equipment with consideration of safety guidelines necessary |

* | * | * |

denotes satisfied criteria.

Abbreviations: Ch, children; env, environment; eq, equipment.

Most of the papers mentioned fractures as one of the most common playground-related injuries. Fractures account for approximately 84% of hospital attendances for children, with an annual incidence rate of 12–42/1000 children.14 Almost all the papers indicated that the majority of fractures involved the upper extremities, and that the main cause was falls.6,14,15,30–33 Falls were reported as the cause of injures in playgrounds, and fractures as the outcome, in at least 50% of the reviewed articles.

Prevention of fractures in childhood was the main reason reported for wanting safer playgrounds.2,10,14 Safety promotion in playgrounds is paramount for both injury prevention and improving attitudes of parents towards environmental safety. Seven papers emphasized the need for preventive safety planning in playgrounds, and three of these recommended safety auditing.

Enforcement of appropriate standards for playgrounds would make these places safer for children. There is some experience of the positive effects of the implementation of playground standards around the world. For instance, in 1931, the National Parks Association in the US introduced some requirements on safe surfaces, and the National Recreation and Parks Association introduced a protocol for playground safety audits in the 1990s. Another example is the Canadian Standards Association’s guideline (CAN/CSA-Z614-07) for children’s playspaces and equipment.7,9,16 The most recent version of this standard was implemented in 136 elementary schools in Toronto, resulting in fewer school playground injuries.16 However, existing standards and guidelines are not enough for injury prevention in playgrounds, and related standards7 need revision.9

Standardization of playgrounds was mentioned in 30% of the studies reviewed. Use of appropriate materials for playground surfaces, and determination of appropriate dimensions for both equipment and free space around equipment was recommended by approximately 50% of these studies. One Australian study emphasized the need for standardization and safety audits as part of playground safety planning.33 The time interval during which injuries were most likely to occur in playgrounds was determined to be 3 pm to 9 pm, as well as on weekends and public holidays. The main age group in terms of injury exposure was 6–10 years-old.6

Discussion

The main findings of these papers highlight the importance of safety promotion and injury prevention in playgrounds and removing high-risk equipment. Implementation of standards, recognition of falls and fractures as high-risk events, and addressing concerns of parents about unsafe neighborhoods were also referred to in these papers. However, it is acknowledged that accidents ranging from minor to severe will still occur in playgrounds, despite implementation of standards and guidelines.

All of the papers, with the exception of one, did not institute any practical playground safety plan, and engineering approaches including safety analysis techniques, eg, failure mode and effect analysis and fault tree analysis, were largely ignored. Most of the reviewed papers did not mention any key points for effective implementation of standards in playgrounds. As shown in Table 2, all of the papers reviewed included a specific approach for selection of playground equipment, but only two mentioned environmental factors, and only four referred to the characteristics of children themselves as an important consideration in playground injury prevention.

Issues relating to public safety include environmental planning, public health, socioeconomic concepts, and community safety. In this regard children are a particularly vulnerable group. According to the research reviewed here, most of the relevant expert opinions and organizations emphasized the importance of playground injury prevention, but playground-related safety problems and injuries continue to be an issue.

There is a close relationship between safety promotion and the community. Playground safety needs plans based on integrated cooperation in communities. This is a multifactorial process, which needs to be accommodated in safety planning, as playground injury prevention is a planned process, involving the participation of children themselves.35 Additional keywords we identified in our literature review include falls, surface, height, fractures, monkey bars, slides, upper extremity, injury, children, play, and childhood development, so future approaches that include these terms may help us to formulate practical guidelines for the prevention of playground injuries. In this regard we recommend a “safety circle”, which may be able to address most playground safety issues. Figure 2 makes some recommendations for playground safety promotion and playground-related injury prevention, and has three main components, ie, equipment, environment, and children.

Figure 2.

Recommended Safety Circle (SC).

Equipment

Safety audits and risk assessments should be performed for all playground equipment. Swings, climbers, and slides in particular are known to be high-risk for injury, so an in-depth safety audit of their safety and supervision requirements is essential.

Environment

Environmental characteristics are divided in two parts, ie, hazards and physical features. Environmental hazards include noise, poor lighting, and air pollution. Physical environmental features include signage, graphics, and a esthetic concepts, and can be used to enhance safety.

Children

The physical and behavioral characteristics of children should also be surveyed. Generally, play-related behavior in children can be considered risky, given that children love excitement and adventure, and this needs to be taken into account when planning for safer and healthier playgrounds. Because there is no correlation between children’s motor abilities and risk-taking behavior, assessment of children’s behavior requires more in-depth observation.34 Study of body types and anthropometric measurements may be needed to achieve a better match between playground equipment and children’s physical characteristics.

The safety circle approach may meet some other needs in playground safety planning as well, including:

Integration of safety systems and urban planning

Devising a pathway for documentation of all near-miss injuries, and actual injuries and events, from source of risk through to treatment or emergency presentation to hospital

Safety audits and proper supervision in playgrounds

Public education on playground safety

Cooperation of nongovernment organizations in safety promotion

Specific studies about environmental factors (ie, hazardous material, illumination, noise pollution, visual pollution), and characteristics of children themselves (ie, anthropometric measurements, behavior, and attitude surveys)

In addition, the following measures would enable better conditions for children’s safety in playgrounds:

Practical research in developing countries

Making reliable databases for playground-related child accidents in low-income countries

Investigation of any existing standards so that revisions can be made to overcome existing safety problems in playgrounds

More research and surveys about the safety of children in public playgrounds

There is a clear need for better recognition of childhood safety issues and for more child playground safety studies. Despite the gravity of the problem, the number of relevant studies reported in the scientific literature is low. Playground accidents are more common in developing countries than in developed countries, but most of the research and literature thus far comes from high-income countries.23 Also, population density is a risk factor for childhood accidents in developing countries, so playground safety assessment in high-risk communities is mandatory. Comparison of accident types and rates between developing and developed countries should be investigated further to enable appropriate audit methods and planning to be formulated particularly for developing countries, although adaptation of safety measures and recommendations would be required according to the economic and cultural characteristics of local communities.

In this review, we have hopefully paved the way for the introduction of an effective approach to the promotion of playground safety and prevention of childhood injuries. Playground safety is important, and therefore global endeavors for safety promotion and injury prevention in playgrounds are warranted.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Rainham D. Do differences in health make a difference? a review for health policymakers. Health Policy. 2007;84:123–132. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvy A, Towner E, Peden M, Soori H, Bartolomeos K. Injury prevention and the attainment of child and adolescent health. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:390–394. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.059808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UN Habitat Second African Ministerial Conference on Housing and Urban Development Available at: www.unhabitat.orgAccessed July 30, 2010

- 4.World Health Organization World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision Available at: www.who.intAccessed December 14, 2009

- 5.Safe Communities Available at: http://www.phs.ki.se/csp/who_safe_communities_en.htmAccessed August 12, 2010

- 6.Tan N, Ang A, Heng D, Chen J, Wong HB. Evaluation of playground injuries based on ICD, E codes, International Classification of External Cause of Injury Codes (ICECI), and abbreviated injury scale coding systems. Evaluation of playground injuries based on ICD, E codes, International Classification of External Cause. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2007;19:18–27. doi: 10.1177/10105395070190010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollman DR. Epidemiology of playground equipment-related injuries to children in the United States, 1996–2005. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:66–71. doi: 10.1177/0009922808321898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loder R. The demographics of playground equipment injuries in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nixon JW. Injury and frequency of use of playground equipment in public schools and parks in Brisbane, Australia. Inj Prev. 2009;9:210–213. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKay M. Playground injuries. Inj Prev. 2003;9:194–196. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macarthur C, Hu X, Wesson De, Parkin PC. Risk factors for severe injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Acc Anal Prev. 2000;32:377–382. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nabors L, Willoughby J, Leff S, McMenamin S. Promoting inclusion for young children with special needs on playgrounds. J D Phys Disabil. 2001;13:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart R. Containing children: some lessons on planning for play from New York City. Environ Urban. 2002;14:153–148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiissel DG. Severity of playground fractures: play equipment versus standing height falls. Inj Prev. 2005;11:337–339. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.009167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherker S. Development of a multidisciplinary method to determine risk factors for arm fracture in falls from playground equipment. Inj Prev. 2003;9:279–283. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard AW. The effect of safer play equipment on playground injury rates among school children. CMAJ. 2005;172:1443–1446. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen HS. Developing a playground injury prevention plan. J School Nurs. 2008;24:131–137. doi: 10.1177/1059840532143214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heck A, Collins J, Peterson L. Decreasing children’s risk taking on the playground. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34:349–352. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Child and adolescent injury prevention: A global call to action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell EC, Ambardekar EJ, Sheehan KM. Poor neighborhoods: safe playgrounds. J Urban Health. 2005;82:403–410. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack GM.Playground injuries in the 90’s. Parks & Recreation 1998Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1145/is_n4_v33/ai_20552696Accessed June 13, 2011

- 22.Rizvi NS. Distribution and circumstances of injuries in squatter settlements of Karachi, Pakistan. Acc Anal Prev. 2006;38:526–531. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . World report on child injury prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and United Nations Children’s Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britton J. Preventing fall injuries in children. WMJ. 2005;1:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roderick LM. The ergonomics of children in playground equipment safety. J Safety Res. 2004;35:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cradock A, Kawachi I, Colditz GA, et al. Playground safety and access in Boston neighborhoods. Am J Prev Med. 2005;4:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moorin RE. The epidemiology and cost of falls requiring hospitalisation in children in Western Australia: a study using linked administrative data. Acc Anal Prev. 2008;40:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farley TA, Meriwether RD, Baker ET, Watkins LT, Johnson CC, Webber LS. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1625–1631. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norton C, Nixon JJ, Sibert J. Playground injuries to children. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:103–108. doi: 10.1136/adc.2002.013045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laforest S. Surface characteristics, equipment height, and the occurrence and severity of playground injuries. Inj Prev. 2001;7:35–40. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahadev AM. Monkey bars are for monkeys: a study on playground equipment related extremity fractures in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherker S. Out on a limb: risk factors for arm fracture in playground equipment falls. Inj Prev. 2005;11:120–124. doi: 10.1136/ip.2004.007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell R. Falls from playground equipment: will the new Australian playground safety standard make a difference and how will we tell? Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18:98–104. doi: 10.1071/he07098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwebel DC, Binder SC, Sales JM, Plumert JM. Is there a link between children’s motor abilities and unintentional injuries? J Safety Res. 2003;34:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4375(02)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corsi M. The child friendly cities initiative in Italy. Environ Urban. 2002;14:169–179. [Google Scholar]