Abstract

Polycomb group response elements (PREs) play an essential role in gene regulation by the Polycomb group (PcG) repressor proteins in Drosophila. PREs are required for the recruitment and maintenance of repression by the PcG proteins. PREs are made up of binding sites for multiple DNA-binding proteins, but it is still unclear what combination(s) of binding sites is required for PRE activity. Here we compare the binding sites and activities of two closely linked yet separable PREs of the Drosophila engrailed (en) gene, PRE1 and PRE2. Both PRE1 and PRE2 contain binding sites for multiple PRE–DNA-binding proteins, but the number, arrangement, and spacing of the sites differs between the two PREs. These differences have functional consequences. Both PRE1 and PRE2 mediate pairing-sensitive silencing of mini-white, a functional assay for PcG repression; however, PRE1 requires two binding sites for Pleiohomeotic (Pho), whereas PRE2 requires only one Pho-binding site for this activity. Furthermore, for full pairing-sensitive silencing activity, PRE1 requires an AT-rich region not found in PRE2. These two PREs behave differently in a PRE embryonic and larval reporter construct inserted at an identical location in the genome. Our data illustrate the diversity of architecture and function of PREs.

Keywords: Polycomb, Polycomb group response elements (PREs), transcriptional repression

THE Polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group (TrxG) proteins are key regulators of genomic programming and differentiation in multicellular organisms. In Drosophila, PcG proteins work as multiprotein complexes recruited to specific regions in the DNA [Polycomb group response elements (PREs)] to heritably repress target gene expression through post-translational covalent modifications of histones and modulation of chromatin structure. Three major complexes have been extensively discussed [Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1), PRC2, and Pho-RC but as more types of tissue, developmental stages, and purification techniques have been used, a number of other complexes have been identified: PR-DUB (Scheuermann et al. 2010), dRAF, and Pcl-PRC2 (reviewed in Kerppola 2009; Müller and Verrijzer 2009; Simon and Kingston 2009).

Of the characterized Drosophila PcG complexes, only Pho-RC contains a DNA-binding PcG protein [Pho or Pho-like (Phol)] that binds directly to PREs (Brown et al. 1998, 2003). Pho-RC consists of Pho or Phol and dSfmbt (Klymenko et al. 2006; Grimm et al. 2009). Scm (Sex combs on midleg) has genetically and physically been shown to interact with dSfmbt (Grimm et al. 2009), and it has been proposed that Scm may interact with an as-yet-unidentified DNA-binding protein and cooperate with Pho-RC to recruit PRC1 and PRC2 (Wang et al. 2010). PRC2 is composed of E(z) (Enhancer of zeste), Esc (Extra sex combs), Su(z)12 (Suppressor of zeste 12), and Nurf55. PRC2 trimethylates H3K27 through the histone methyltransferase activity of the E(z) SET domain to set a repressive mark (Cao et al. 2002; Czermin et al. 2002; Müller et al. 2002). A variant of PRC2, Pcl-PRC2, is required for high levels of H3K27me3 (Nekrasov et al. 2007). The PRC1 core complex is composed of Ph (Polyhomeotic), Psc (Posterior sex combs), Pc (Polycomb), and Sce (Sex combs extra), also known as dRing (Shao et al. 1999; Fritsch et al. 2003). dRing/Sce has a ubiquitin ligase function (Wang et al. 2004). dRaf is a variant of PRC1 that has demethylase activity and removes an active mark from histone H3K36me2 and replaces it with repressive ubiquitylation at H2A-K118 (Lagarou et al. 2008). PR-DUB has deubiquitinase activity in vitro (Scheuermann et al. 2010). Multiple orthologs of the PcG genes are present and play major roles in differentiation, stem cell maintenance, and cancer in mammals (reviewed in Gieni and Hendzel 2009).

Central to PcG repression is the recruitment of PcG proteins to the PRE (reviewed in Müller and Kassis 2006; Schuettengruber, et al. 2007; Kassis and Brown 2013). PREs from a number of genes have been closely examined, including four PREs from the engrailed (en) and invected (inv) genes (Americo et al. 2002; Cunningham et al. 2010); bxd, iab2, and iab7 (also known as Fab-7) PREs from the bithorax complex (BX-C; Hagstrom et al. 1997; Shimell et al. 2000; Busturia et al. 2001; Mishra et al. 2001; Dejardin et al. 2005); and an evenskipped (eve) PRE (Fujioka et al. 2008). PREs are made up of binding sites for many different proteins including Pho/Phol (Brown et al. 1998, 2003; Fritsch et al. 1999), Spps (Sp1 factor for pairing-sensitive silencing) (Brown and Kassis 2010); GAGA factor (GAF); and Dsp1. Grainy head (Grh), and Zeste have also been implicated in PRE function (reviewed in Müller and Kassis 2006; Schuettengruber et al. 2007; Kassis and Brown 2013). Genome-wide studies show that not all of these factors are bound to every PRE although Pho/Phol seems to be a key component of most PREs. Genome-wide studies of Spps have not yet been reported.

Despite knowing a number of factors that bind directly to PREs, it is not possible to identify PREs based on DNA sequence alone. PRE predictions based on clustering of DNA-binding sites within a given region identify only ∼10–15% of PREs identified by genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments with components of the PcG complexes (Ringrose et al. 2003; Fiedler and Rehmsmeier 2006; Schuettengruber et al. 2009). Some PRE-binding proteins are still not identified (Americo et al. 2002). It may be that there is no one size that fits all formula for PREs. Differences in DNA sequence and transcription factor-binding site composition might be important for different types of PREs and allow PcG activity to respond to different cell-type-specific cues. Genome-wide ChIP has shown differences in the binding patterns of PcG proteins/complexes in different cell types (Negre et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2006; Tolhuis et al. 2006; Kwong et al. 2008; Oktaba et al. 2008; Schuettengruber et al. 2009). Initially thought to act as a simple off/on switch, regulation by the PcG proteins has the ability to dynamically respond to changing needs during development.

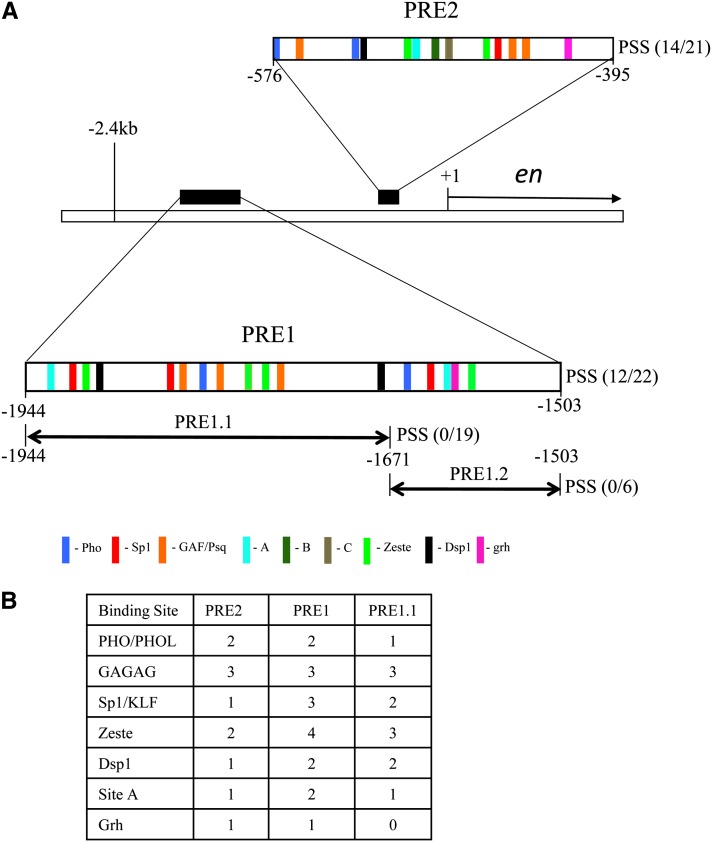

en is a segment polarity gene that is a target of PcG repression (Moazed and O’Farrell 1992). The regulatory sequences of en span ∼70 kb. Embryonically, en is expressed in a complex manner, in stripes, in the peripheral and central nervous system, the fat body, and portions of the head. In larvae, en is expressed in the posterior compartments of imaginal discs and in a subset of cells of the nervous system. A 2-kb region extending from −2.4 kb to −395 bp upstream of the en transcription start site contains two PREs (PRE1 and PRE2) (DeVido et al. 2008; see Figure 1). This 2-kb piece of DNA has PRE, pairing-sensitive silencing (PSS), and homing ability (Kassis 1994, 2002; DeVido et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2012). In addition to silencing, these PREs can act with distant enhancers to facilitate transcriptional activation (DeVido et al. 2008; Kwon et al. 2009). Here we focus our efforts on analyzing different aspects of the en PREs and determining what DNA sequences are needed to specifically constitute an en PRE. Our data show that there are differences in the DNA sequence requirements of the two closely linked PREs in the PSS assay. Furthermore, these two PREs behave differently in embryonic and larval functional assays. Our data refute the idea that all PREs are the same, an important point in understanding recruitment and functioning of the PcG system of repression at such complex developmental target genes.

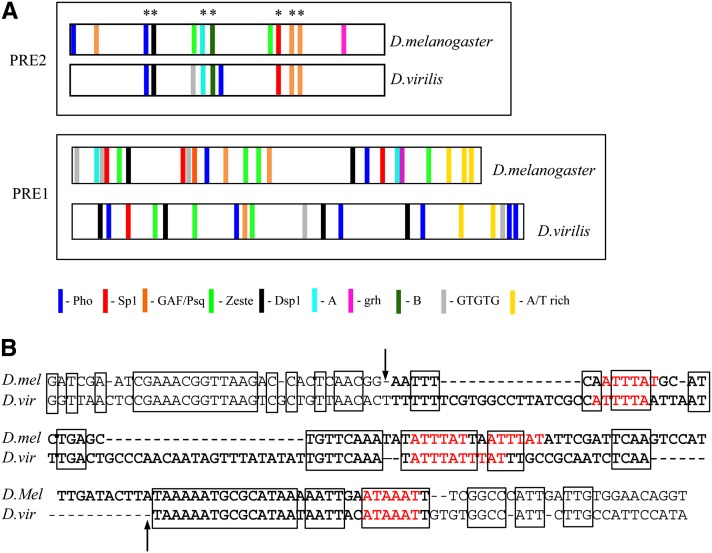

Figure 1.

Predicted binding sites in PRE1 and PRE 2. (A) A schematic drawing of the genomic region of the en locus showing the en transcription unit and the two upstream PREs, PRE1 and PRE2 (DeVido et al. 2008). Each PRE is shown as an enlargement with predicted binding sites/consensus sequences represented by color-coded bars using the following consensus sequences: Pho-GCCAT; GAF/Psq-GAGAG; Zeste-BGAGTGV or YGAGYG (Mohrmann et al. 2002; Ringrose et al. 2003) (B = C,T, or G; V = A, C, or G; Y = C or T); Sp1/Klf-RRGGYG (R = A or G) (Shields and Yang 1998); Dsp1-GAAAA (Dejardin et al. 2005), Grh-TGTTTTTT or WCHGGTT (W = A or T; H = A, T, or C) (Blastyak et al. 2006; Venkatesan et al. 2003; Almeida and Bray 2005); site A-GAACNG. (N = A, C, T, or G). PRE1 (−1944 to −1503) when subdivided into PRE 1.1 or PRE 1.2 leads to loss of PSS with either fragment. The relative positions of sites B and C in PRE2 are shown (Americo et al. 2002). We did not include sites B or C in our binding site analysis since mutation of site C did not affect PSS and site B has not been fully defined or tested in a functional assay. (B) A comparison of the number of predicted consensus-binding sites for each factor in PRE1, PRE1.1, and PRE 2.

Materials and Methods

P-element transgene constructs

These constructs were made as described in Americo et al. (2002). Mutations of individual sites within the PREs were generated by PCR with mutated oligonucleotides. The oligonucleotides incorporated EcoRI and BamHI restriction endonuclease site ends to facilitate cloning. The PCR products were cloned into the EcoR1-BamHI sites of pCaSpeR (Pirrotta 1988). The clones were confirmed by sequencing. Transgenic fly lines were generated by Genetic Services Inc.

Cloning and injection of φC31 constructs

PRE1 or PRE2 DNA was amplified using oligonucleotides with XbaI restriction site ends and cloned into the XbaI site of the PRE300-bxd-Ubx-Z plasmid (Fujioka et al. 2008) in place of the eve PRE. The PREs were cloned in the same orientation with respect to the Ubx promoter as they are with respect to the en promoter at the endogenous en locus. Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) was performed as described by Bateman et al. (2006) into the attP site located at 52D (injections by Genetic Services). The integrity of the RMCE products were confirmed by PCR, and the constructs used here were all inserted in the same orientation to minimize variability.

Gel mobility shift assays

Gel mobility shift assays were performed as described in Americo et al. (2002) except that they were carried out using 3 μl of commercially prepared SL2 extracts from Active Motif in place of embryonic nuclear extracts or with full-length recombinant Pho protein synthesized in vitro using the TNT-coupled transcription/translation system from Promega. The sequences of the Pho1–4 probes are Pho1 AAAGGCAGCCATTTTCC, Pho2 CACATGGCCATCTCTTTC, Pho3 GGCAGCCATTGTTGTCA, and Pho4 GTCAGCCATTAAAAGTC.

Searching known PREs for predicted protein-binding sites

The en, eve, and iab7/Fab-7 PREs were searched for the presence of consensus binding sites using GenePalette (http://www.genepalette.org) (Rebeiz and Posakony 2004).

Cross-linked chromatin immunoprecipitation

Imaginal discs along with the central nervous system, mouth hooks, and some anterior cuticle were dissected from third instar larvae (20 larvae per sample) and immediately placed in Schneider’s medium (Invitrogen) on ice. The disc sets were fixed in 2% formaldehyde (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) fixing solution (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA) for 15 min and then rinsed in stop solution (PBS, 0.01% Triton X-100, 0.125 M glycine) for 10 min, followed by 2 × 10 min washes with wash solution (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 0.25% Triton X-100). Fixed and washed discs were stored at −80° in storage solution (10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA). The storage buffer was replaced with 300 μl of action buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA), supplemented with Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube, and sonicated in BioRuptor (Diagenode, Denville, NJ) for 30 sec on/30 sec off (20 cycles) at high power. The sonication resulted in chromatin fragments tightly concentrating at 200 bp, with a diminishing smear up to 1500 bp. Remaining insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the chromatin supernatant was transferred to a new tube. One percent of total volume was saved from each sample for input reactions. ChIP was performed with 1:200 dilution of the required antibody (Grh antibody, Kim and McGinnis 2011; H3K27me3 antibody, Millipore) and the Protein A agarose Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay Kit from Millipore according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cross-links were reversed by incubating at 65° for 4 hr with 100 mM NaCl. All samples were then purified with standard phenol/chloroform extraction. DNA samples were ethanol-precipitated overnight, washed with 75% ethanol, and resuspended in 100 μl of water.

Quantitative PCR analysis of cross-linked chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP samples were analyzed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using a Lightcycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Applied Science) and Lightcycler 480 DNA SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche Applied Science) according to manufacturer instructions. All samples are given as percentage input. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Primer sets were the following:

PRE1 F: TGAACAGCTCAGATGCATAAATTG

PRE1 R: CAGACTGGAAGGTGCGTTC

PRE2 F: GCTTATGAAAAGTGTCTGTG

PRE2 R: GGGGCTTGTTAGGCAGCAAT

En control F: CGCCTTAAGGTGAGATTCAGTT

En control R: GGCGGTGTCAATATTTTGGT

PRED F: CGAAATGCTACTGCTCTCTA

PRED R: GCGTAGTCTTATCTGTATCT

Ubx control F: CCAGCATAAAACCGAAAGGA

Ubx control R: CGCCAAACATTCAGAGGATAG.

PRE/bxd for PRE1 F: GCATCTGCGCTGTTCA

PRE/bxd for PRE2 F: CGGTAACGCCCCGTGAG

PRE/bxd R: TCGAGCAGCCCTGTTG

Bxd/Ubx F: GCCACATTTCCAGTTTCGACTTGC

Bxd/Ubx R: AGTTCTTGCTACATCATGCAGTTATTG

LacZ F: CAGCCGTTTGCCGTCTGAATTTGA

LacZ R: TGGAAATCGCTGATTTGCGTGGTC.

Results

Analysis of predicted protein-binding sites in en PREs

PREs were first identified as fragments of DNA from the BX-C that could mediate repression by the PcG genes in embryonic reporter constructs (Müller and Bienz 1991; Simon et al. 1993). The ability of a fragment of DNA to mediate PcG repression in a reporter construct is known as the PRE-maintenance assay. PREs act in transgenes to mediate the phenomenon of PSS of the mini-white gene (Kassis et al. 1991; Kassis 1994, 2002). While there is some controversy as to whether all fragments of DNA that mediate PSS are PREs (Kassis 2002), in our studies of PREs from the en/inv region we have found a 100% correlation of fragments that demonstrate PRE activity in the maintenance assay and fragments that give PSS (Americo et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2005; Cunningham et al. 2010). Here, we assay PSS of mini-white in transgenic lines carrying PREs with mutated binding sites to assess if a given binding site might play a role in PRE activity. This is a P-element-based system with random integration into the genome. The ability to mediate PSS relies to some extent on the site of insertion, and only ∼60% of insertion sites give PSS with the wild-type PRE.

To date, four well-defined binding sites in PRE2 have been shown to be required for its PSS activity; these are binding sites for the proteins Pho/Phol, Spps, GAF, and Dsp1 (Brown et al. 1998, 2003; Decoville et al. 2001; Americo et al. 2002; Dejardin et al. 2005). Chromatin-immunoprecipitation studies show that these four proteins localize to the en PREs as well as to many other PREs in the genome (Klymenko et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2006; Schuettengruber et al. 2009; Brown and Kassis 2010). Furthermore, PSS is disrupted in pho, Dsp1, and Spps mutants, showing that these proteins are required for the PSS activity of PRE2 (Brown et al. 1998; Dejardin et al. 2005; Brown and Kassis 2010). Here we define other binding sites required for PSS activity of PRE2 and compare the results with sequences required for PRE1 activity. Figure 1 shows the locations of PRE1 and PRE2 in relation to the en transcription start site and the locations and numbers of putative binding sites for proteins implicated in PRE activity. We included in our analysis the consensus sequences for the Grh and Zeste proteins as both have been implicated in the activity of some PREs (Saurin et al. 2001; Hur et al. 2002; Tuckfield et al. 2002; Mulholland et al. 2004; Blastyák et al. 2006).

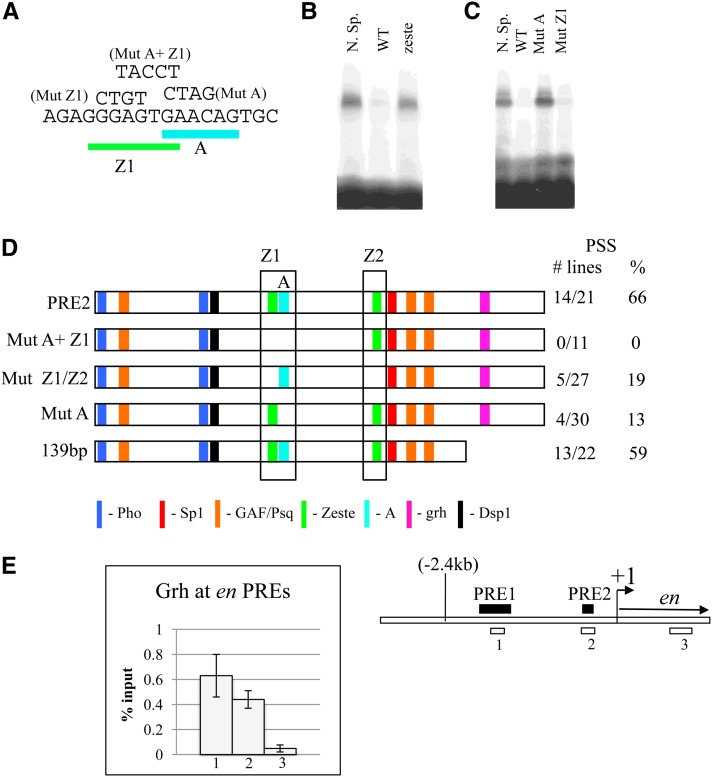

Identification of site A

In previous studies we identified a protein-binding site within an 18-bp region of PRE2 (AGAGGGAGTGAACAGTGC), (Americo et al. 2002 and Figure 2). Mutation of the central region of this site (AGTGA to TACCT) caused a complete loss of PSS (Americo et al. 2002). Closer examination of this 18-bp sequence showed that it contains a match to the consensus binding sequence for the Zeste protein (the sequence GGAGTGA matches the Zeste consensus site BGAGTGV) (see Figure 2A). We used gel mobility shift analysis and competition with oligonucleotides to determine the critical nucleotides for binding to the 18-bp oligonucleotide. Our data showed there was binding to a sequence (site A) bound by an unknown protein (Protein A) that overlaps the Zeste consensus sequence (Figure 2). The Protein A gel mobility shift was not competed by an oligonucleotide containing known Zeste-binding sites (CGAGTGAGTGTGAGTG; Figure 2B). Furthermore, mutation of the Zeste consensus sequence within the 18-bp sequence (Mut Z1) still competed the gel shift, whereas mutation of site A disrupted the competition, indicating that these were the critical nucleotides for binding (Figure 2C). We introduced a mutation that disrupts site A in PRE2 and assayed this mini-white reporter construct in transgenic flies for the ability to give PSS (Figure 2D). When site A was mutated, PSS was reduced from 66% to 13% of the lines (comparable to what we see with mutation of either the Pho or the Spps sites) (Americo et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2005). We have identified the potential core-binding site of protein A to be GAACAG. This is where the mutations of the binding site are centered, and, in addition, another oligonucleotide containing GAACAG was able to compete the site A gel mobility shift (data not shown). We are currently trying to identify the protein that binds to site A.

Figure 2.

Defining site A and ChIP with αGrh. (A) The sequence of the Z1/A 18-bp annealed oligonucleotide used in the gel mobility shift assays with Schneider cell extract (SL2) shown in B and C and the mutant sites tested: Zeste site (Mut Z1), site A (Mut A), and the Zeste/siteA double mutant (Mut A+Z1). The mutated bases are shown for each site, and altered bases were made in the context of the 18-bp oligo sequence. (B) Gel mobility shift assay using SL2 extract on the Z1/A oligo with 50× competition with unlabeled nonspecific competitor (Sp1/KLF site, TCACGGGGCGTTACCGAG) (Brown et al. 2005), the wild-type Z1/A oligo, and an oligo known to bind the Zeste protein (CGAGTGAGTGTGACTG). The known Zeste-binding site does not compete. (C) Gel mobility shift assay on the Z1/A oligo showing competition with the Z1/A oligo with a mutated site A or a mutated Zeste site. “N.Sp” (nonspecific) is competition with the Sp1/KLF-binding site oligo, and “WT” (wild type) represents the unmutated Z1/A oligo. (D) Effect of binding-site mutations in PRE2 on PSS activity. The location of the Z1/A oligo is boxed. PSS is given as the number of lines and as a percentage. The 139-bp construct is a minimal PRE2 sequence that was previously described in Americo et al. (2002). The effect of mutating Z1 or Z2 individually has not been tested. (E) Grh/ChIP at en PRE1 and PRE2 in imaginal disk and CNS material isolated from third instar larvae. Grh ChIP was carried out three times with two different Grh antibodies (rabbit or guinea pig) (Kim and McGinnis 2011). The graph represents two independent experiments using the guinea pig Grh. A schematic on the right shows the approximate position of each oligonucleotide set. ChIP values are plotted as percentage input, and error bars are shown.

Zeste/Fs(1)h-binding sites

The Zeste consensus-binding site CGAGTG has also been shown to bind the protein female sterile (1) homeotic [Fs(1)h] (Chang et al. 2007). PRE2 has two matches to this consensus sequence, the one next to site A and the one in the middle of the fragment (Z2, CGAGTG). Mutation of both matches to the Zeste consensus sequence reduced PSS to 19%. Mutation of the adjacent Zeste and A sites together gave no PSS more severe than either of the mutated sites alone. Thus, both of these consensus sequences contribute to the PSS activity of PRE2. Note that in our gel mobility shift assays we do not detect a shift due to a factor binding to the Zeste consensus sequence (data not shown). The protein that binds this site may not be present in the S2 extracts used for these experiments or may require cooperative interaction of more than one binding site as has been shown for Zeste binding at other regulatory regions (Benson and Pirrotta 1988).

Zeste mutants do not affect PSS by PRE2

Zeste has been implicated in PRE activity due to its association with PRC1 (Saurin et al. 2001; Hur et al. 2002; Mulholland et al. 2003), but it has also been linked to TrxG-mediated activation (Dejardin and Cavalli 2004). Genome-wide ChIP-chip studies show a limited overlap of Zeste protein binding with PcG protein binding in embryos, but Zeste was bound to the en PREs during embryogenesis (Moses et al. 2006). We tested whether a mutation in zeste (za) affected PSS by PRE2; in heterozygous and homozygous za mutants, there was no change in PSS of mini-white in flies carrying PRE2-mini-white constructs (data not shown). Therefore, Zeste is not the protein working at these sites in later development. It is possible that Fs(1)h is the protein that acts here (Chang et al. 2007).

Grh

Grh has been described as binding to PREs and to cooperatively interact with Pho. The binding site for Grh identified in the iab-7 PRE was reported to be TGTTTTTT (Blastyák et al. 2006). However, other groups report a Grh consensus sequence as WCHGGTT (where W is A or T and H is not G) (Venkatesan et al. 2003; Almeida and Bray 2005). We did not find any match to the TGTTTTTT sequence within en PRE2; however, there is a potential match to WCHGGTT toward the end of PRE2 (Figure 1). The sequence is ACCGGCT (the one position that does not match is underlined). This sequence lies in a region that we have deleted from PRE2 in previous studies and yet still saw PSS (139-bp PRE, shown in Figure 2D) (Americo et al. 2002). The 139-bp PRE was functional but not as robust as the entire 181-bp region. There is a potential match to the Grh consensus in PRE1 (see below). Chromatin immunoprecipitation with an antibody against Grh showed binding of Grh to each of these PREs in tissue derived from third instar larvae (Figure 2E). Grh is the only PRE-binding protein identified so far that does not have ubiquitous expression.

Other factors

We previously showed specific binding of two other proteins (B and C) to sites within PRE2, but we did not know if they were needed for PSS activity (Americo et al. 2002). Mutation of one of these sites (site C) does not impact PSS (data not shown). The binding site for protein B has been narrowed down to a 12-bp region (TGCCGCTATATG), but mutations of this site have not yet been tested in the PSS assay. The positions of these two binding sites relative to the other protein-binding sites in PRE2 are shown in Figure 1A.

Some genome-wide ChIP experiments showed enrichment at PREs for TTG repeats and others found an enrichment of GT repeats (Ringrose et al. 2003; Schuettengruber et al. 2009). Deletion of the GTGT sequences in the PRE of the vestigial (vg) gene led to a reduction of silencing activity of this fragment, suggesting that this sequence may play a role in PcG repression (Okulski et al. 2011). There is only one TGTGT sequence in PRE2 that lies in the region of the 181-bp PRE that can be deleted without affecting PSS. There are three sequences in PRE1 that show GT repeats (GTGTGT or GTGTG). These sites have not been tested within the context of PRE1. To date, the protein that binds to GT repeats has not been identified.

PRE1

PRE1 originally referred to a 2-kb region from −2.4 kb to −576 bp upstream of the en transcription start site. This region acts as a PRE, mediates PSS, and contributes to homing (Kassis 1994; DeVido et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2012). Here we wanted to define the minimal fragment for PRE1. A 441-bp region (−1944 to −1503) encompasses a region showing the most clustering of binding sites associated with PSS/PRE activity (DeVido et al. 2008). In a previous study this fragment gave PSS of mini-white in 3/5 lines, but constructs with the region −1944 to −1671bp (273 bp, PRE1.1) or with −1672 to −1503 (169 bp, PRE 1.2) did not (Kassis 1994) (Figure 1A). We generated additional lines of PRE1 and PRE1.1 and found that 12/22 PRE1 lines gave PSS while 0/19 PRE1.1 lines gave PSS. From here on we use PRE1 to refer to the 441-bp region from −1944 to −1503 bp upstream of the en transcription start site.

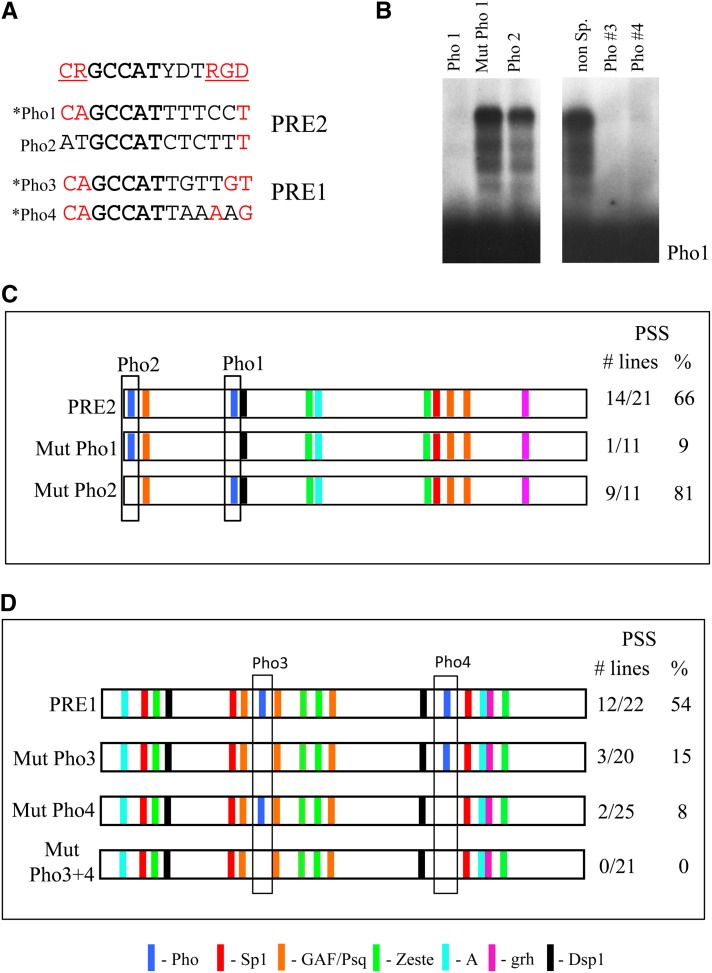

PRE1 and PRE2 differ in their requirements for the number of Pho-binding sites for PSS

Mohd-Sarip et al. (2002, 2005, 2006) proposed a model requiring two Pho sites for in vivo chromatin association of Pho and the Polycomb core complex (PCC) with the iab-7 and bxd PREs. They proposed that sequences around the core consensus Pho-binding site contribute on one side to enhancing PHO binding and on the other side to cooperative binding of Pho and the PRC1 core complex. The consensus sequence that they derived for Pho sites is CRGCCATYDTRGD (R is A or G; D is A, T, or G). CR (underlined) is called the U sequence and is thought to enhance Pho binding. RGD (underlined) is the consensus for the site that is required for association of PCC. When RGD was mutated, both the cooperative binding of Pho with PCC and PSS mediated by the iab-7 PRE were abolished (Mohd-Sarip et al. 2005).

We have previously shown that mutation of a Pho-binding site (Pho1 in Figure 3) greatly diminishes PSS by PRE2 (Brown et al. 1998). PRE2 has a second potential Pho-binding site (Pho2) on the 5′ end of the PRE (Figure 3). However, when this site is used as a competitor in a gel shift assay with in vitro-transcribed/translated full-length Pho bound to the Pho1 site, there is very little competition (Figure 3B). Conversely, when the labeled Pho2 oligo was used in the gel mobility shift assay, no specific gel shift was detected (data not shown). Thus, this second Pho site is at best a very weak binding site for Pho compared to the Pho1 site. However, in the context of the PRE, perhaps a weak site can bind Pho in combination with a high-affinity binding site. We mutated the Pho2-binding site in the context of PRE2 in a transformation vector carrying the mini-white gene and looked for PSS. PSS was unaffected in lines where the Pho1 site was mutated (88% PSS for mutated Pho1 compared to 66% for wild-type PRE2) (Figure 3C). Thus, PRE2 does not require two Pho sites for PSS activity.

Figure 3.

Defining the PHO site requirements of PRE1 and PRE2. (A) Sequences of Pho1-4 lined up with the extended Pho consensus-binding sequence proposed by Mohd-Sarip et al. (2005). The bases that are part of the extended consensus sequence are given in red and are underlined in the consensus site. The bases in boldface are the matches to the core PHO consensus-binding site. Sites that are marked with an asterisk show strong Pho binding. (B) Gel mobility shift analysis of in vitro-transcribed/translated full-length Pho protein binding to the Pho1 site with the inclusion of each of the oligonucleotides in competition. (Left) Binding in the presence of 100× unlabeled Pho1 oligo, Mut Pho1 oligo, and Pho2 oligo. (Right) Full-length PHO protein binding to the Pho1 oligo in competition with a nonspecific oligo and Pho3 and Pho4, respectively. (C and D) Schematic of the predicted binding factor sites in PRE1 and PRE2, respectively. The boxed areas highlight the Pho sites, and the absence of a Pho site in a construct represents mutation of this binding site. The numbers and percentages of lines that give PSS are shown.

There are two predicted Pho sites in PRE1 and both compete as well as the Pho1 site in a gel mobility shift assay using in vitro-transcribed/translated full-length Pho protein (Figure 3B). We note that Pho1, -3, and -4 all give good matches to the U site, whereas Pho2 does not (Figure 3A). These data support the view that the U site enhances Pho binding. In contrast, none of the Pho sites contain a perfect match to the RGD sequence required for recruitment of PCC in vitro (Mohd-Sarip et al. 2005). We introduced mutations that disrupt Pho binding into the Pho3 and Pho4 sites individually and together in PRE1. Disruption of either the Pho3- or the Pho4-binding sites decreased the PSS activity of the fragment (Figure 3D). When both Pho sites were mutated, we saw no PSS. From this, we conclude that the PRE1 requires two Pho-binding sites for full function. Mutation of either site leads to only partial loss of activity. Similarly, mutation of the single Pho site in PRE2 does not completely abrogate function. We suggest that in PRE2 another DNA-binding protein plays the role of the second Pho site for PcG complex recruitment.

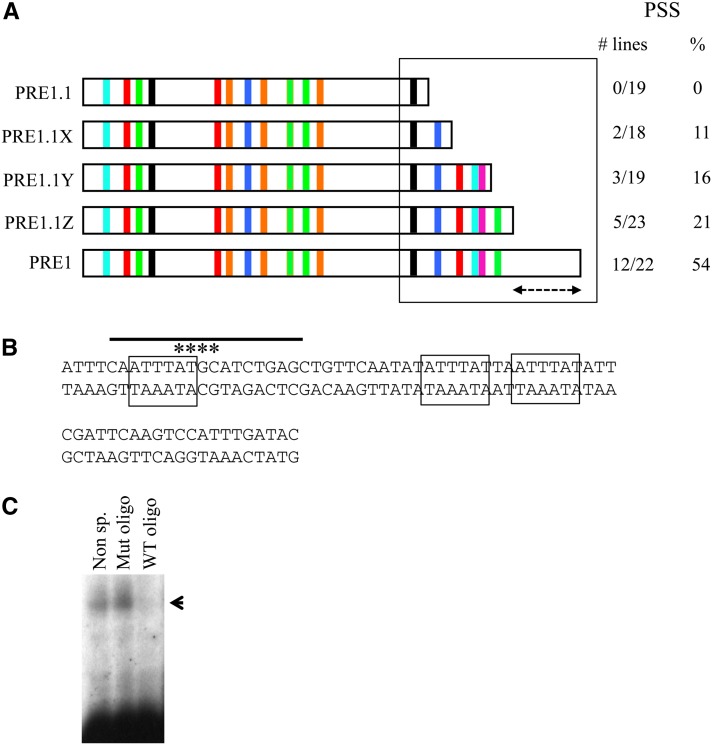

An AT-rich region is required for full activity of PRE1

PRE1.1 contains binding sites for all known factors required for the activity of PRE2, but it has only one of the two Pho sites required for PRE1 activity (Figure 1 and Figure 3). This led to the prediction that adding back the piece of DNA that contains the second Pho site to PRE1.1 might restore full PSS activity to PRE1.1. Surprisingly, adding back the second Pho site only gives PSS in 11% of the lines, which is no better than having a single Pho site (Figure 4A). Clearly, something else is required for the PSS activity of PRE1. We then added back more pieces of DNA from this fragment to see what else was required to recover full PSS activity.

Figure 4.

PRE1 requires an AT-rich region for full activity. (A) Set of constructs made of PRE1. Increasing amounts of PRE1.2 sequence were added back to PRE1.1, and the levels of PSS were observed for each. The predicted binding sites are shown for each construct. (B) The sequence of the AT-rich sequence of PRE1 that is denoted by the dashed line in A above. When this sequence is added to PRE1.1Z, full PSS activity is restored. The boxed sequences are repeats of ATTTAT, and the line above the sequence shows the oligo used for the gel mobility shift assays in C below. The asterisks show the bases that are mutated in a mutant oligo used in competition with the gel mobility shift below. The indicated bases were changed to GCAG. (C) Gel mobility shift analysis of SL2 extract with an oligo spanning one of the ATTTAT repeats. The gel shift is competed by the specific oligo but not by an oligo in which part of the ATTTAT sequence has been mutated. Oligos in which the ATTTAT is mutated in the first AT and the two preceding bases no longer compete with the gel shift (data not shown).

The sequences added back contain consensus-binding sites for a number of factors believed to be involved in PRE activity (Sp1, Site A, Grh, Zeste site) (Figure 4A). As these binding sites are added back, PSS increased from 11% (with the second Pho site) to 21%, but full PSS activity was not restored until we included the entire PRE1 fragment (54%). The last sequence added back did not contain any matches to the binding sites previously identified at the Drosophila PREs. This region of DNA is extremely AT rich (72%) and is perhaps needed for structural reasons such as the ability of the DNA to bend and facilitate long-range interactions (Figure 4B). The sequence contains three repeats of ATTTAT. Gel mobility shift experiments show that at least one factor specifically binds to this sequence (Figure 4C).

Studies of evolutionary conservation of transcription-factor-binding sites in the 12 sequenced species of Drosophila have proven to be a very valuable tool in the study of enhancers; however, they have not been as useful in the study of PREs. PREs seem to have built-in plasticity in the arrangement of potential binding sites, making them very hard to identify when using a best-fit analysis based on homology over large regions (Dellino et al. 2002; Hauenschild et al. 2008). Comparison of the en 2.4-kb region encompassing PRE1 and PRE2 over the 12 Drosophila species showed little conservation between all 12 species. However, when the equivalent region of each species is searched in GenePalette for consensus sequences for the factors that we have discussed here, many of the sites are present. The Pho and GAF/PSQ sites are the most conserved features. Kassis et al. (1989) compared the upstream region of the en gene between D. melanogaster and D. virilis. The corresponding region for PRE2 in D. virilis was identified and shown to give PSS (Kassis 1994), implying that this element most likely contains all the protein-binding sites necessary for PRE function. Using GenePalette, we searched the D. virilis PRE2 sequence for the binding sites that we have studied here. The results are shown in Figure 5A. Between D. melanogaster and D. virilis there is conservation of the Pho and overlapping Dsp1 site, site A, site B, Spps, and GAF/PSQ. There is conservation of a sequence that we have designated site B (GCCGCT), which gives a specific gel shift with Drosophila embryonic extracts (Americo et al. 2002). Not conserved are the Zeste consensus-binding sites, again implying that Zeste is most likely not the protein that binds to these sites. We extended this analysis to look for conservation of PRE1, although we note that this DNA fragment has not been tested for PRE activity. In PRE1, the order and spacing of the predicted binding sites is not conserved, although many of the binding sites are present. Furthermore, there is an AT-rich region at the end of the predicted D. virilis PRE1 including multiple copies of the ATTTAT sequence (Figure 5B). Without further mutational analysis, it is not possible to distinguish between a requirement for general AT richness and a specific protein-binding DNA sequence.

Figure 5.

Comparison of predicted binding sites between D. melanogaster and D. virilis at PRE1 and PRE2. (A) The predicted binding site comparison between PRE1 and -2 of D. melanogaster and D. virilis. See Figure 1 legend for the consensus-binding sequences used. The asterisks denote sites conserved in PRE2. Note that the D. virilis PRE1 fragment has not been tested for PRE activity. (B) Comparison of the AT-rich sequence at the end of PRE1 between D. melanogaster and D. virilis. The arrows delineate the AT-rich sequence of PRE1; extra bases on either side are included. Spaces are introduced to get the best lineup of sequence. The D. virilis sequence contains several ATTTAT sequences (highlighted in red), and boldface indicates the most AT-rich part of the sequence: 72% (83/113 bases) and 77% (111/144 bases) AT richness for D. melanogaster and D. virilis, respectively. Identical sequences are boxed.

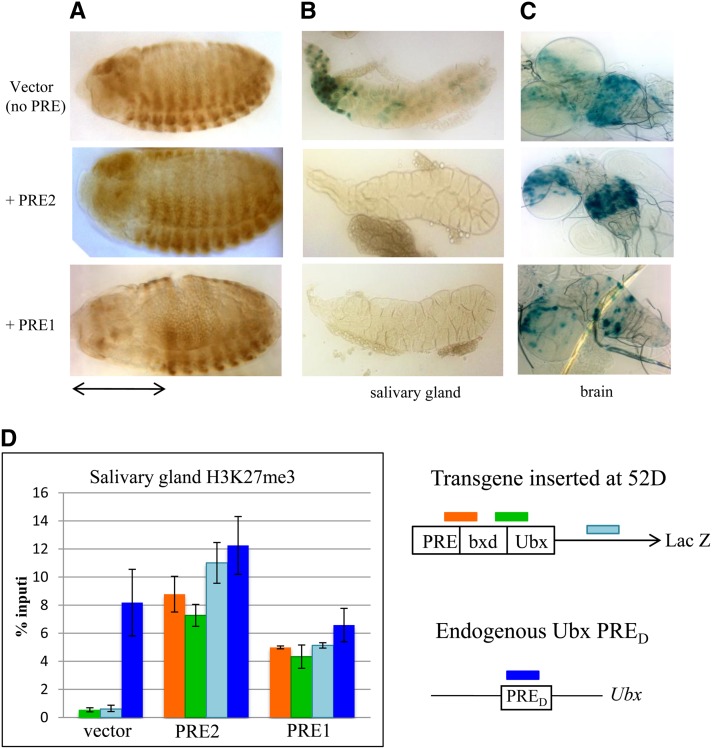

Activity of PRE1 and PRE2 differs in a bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter construct

We have previously shown that PRE2 can act as a PRE-maintenance element in an embryonic bxd-Ubx-lacZ P-element reporter construct (Americo et al. 2002). Furthermore, both PRE2 and PRE1 (contained within a 2-kb fragment) acted as PREs in an embryonic en-lacZ reporter construct, but PRE1 had greater activity in this context (DeVido et al. 2008). To directly compare the activities of PRE1 and PRE2, they were tested in a bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter inserted into the genome using φC31 RMCE (Groth et al. 2004; Bateman et al. 2006) incorporated into the attP insertion site located at 52D (see Bateman et al. 2006). The recombinants generated by this system do not carry the mini-white gene; therefore PSS cannot be assessed at this location. This vector and insertion site was previously used to demonstrate the embryonic maintenance activity of the eve PRE (Fujioka et al. 2008). Based on genome-wide studies of H3K27me3 in embryos (Schuettengruber et al. 2009), the 52D insertion site does not lie in an H3K27me3 domain. Embryos with vector alone, PRE1 vector, and PRE2 vector were stained with an antibody against β-galactosidase (β-gal). In the absence of a PRE, bxd-Ubx-lacZ is expressed in parasegments 6–13 early in development, but later becomes derepressed and is expressed throughout the entire embryo (Figure 6A). PRE1, but not PRE2, was able to maintain the restricted expression of bxd-Ubx-lacZ in this chromosomal insertion site (Figure 5A). That PRE2 did not maintain repression was somewhat surprising, since we previously showed that it was able to maintain the restricted pattern of the same bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter gene at 9 of 12 chromosomal insertion sites in a P-element-based vector (Brown et al. 2005). With RCME, constructs were inserted in the genome in either orientation, and similar results were obtained from both orientations. This shows that there is a difference in how PRE1 and PRE2 work in embryos at the 52D insertion site.

Figure 6.

Activity of PRE1 and PRE2 in the Ubx-lacZ reporter construct inserted at 52D in embryos and larval tissues. (A) Anti-β-gal-stained embryos, (B) salivary glands, and (C) brains from transgenic lines carrying a bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter gene inserted at 52D. (B, C) β-gal activity assay. Staining is shown for transgenic lines carrying vector alone, vector + PRE2, and vector + PRE1. The embryos shown are stage 14 (anterior left, dorsal up). The double-headed arrow highlights the repression of lacZ expression in late-stage embryos carrying the PRE1 construct but not the vector alone or the construct carrying PRE2. Salivary gland staining is seen only with the vector and not with the constructs carrying PRE1 or PRE2. Brain staining is seen in a specific pattern that is reduced in the flies carrying PRE1 but not in the flies carrying PRE2. (D) ChIP with anti-H3K27 on third instar larval salivary glands of transgenic lines carrying the bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter gene inserted at 52D (see Bateman et al. 2006). Results are shown for vector only, vector + PRE2, and vector + PRE1. qPCR was carried out with transgene-specific primers spanning the PRE/bxd junction, the Ubx/lacZ junction, and within the lacZ gene. Primers from the endogenous PRE of the Ubx locus (PRED) were used as a positive control in each of the transgenic lines. Values are given as percentage input, and error bars represent the variation between experiments.

We next examined the lacZ expression in the bxd-Ubx-lacZ larvae, with and without the PREs (Figure 6A). In larvae with vector alone, β-gal activity was detected in the salivary glands and in a subset of cells in the brain. This pattern of expression was not due to the insertion site since a similar pattern was observed using the same vector inserted into an attP site at 95E (Fujioka et al. 2008; data not shown). Addition of PRE2 into the vector abrogated expression of β-gal in the salivary glands but not in the brain of the transgenic larvae. Addition of PRE1 to the vector abrogated β-gal expression in the salivary gland and greatly reduced the number of cells in the brain that express β-gal. To investigate whether the repression of β-gal activity was due to the action of the PcG proteins, we assayed for the presence of H3K27me3 on the transgene by chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by qPCR. H3K27me3 is a signature of PcG activity, and Ubx PRED is included as a positive control. In larvae with vector alone, H3K27me3 is not associated with the lacZ gene in either the brain or the salivary glands. In contrast, salivary glands from flies with vector plus PRE1 or PRE2 have H3K27me3 associated with the lacZ gene. The fact that PRE2 can act as a PRE in the salivary glands, but not in the brain or embryo, suggests that either its activity is tissue specific or that the large number of closely aligned transgenes present in the polytene chromosomes potentiated the activity of PRE2, allowing it to overcome the activity of the transcriptional activators acting on this construct.

Discussion

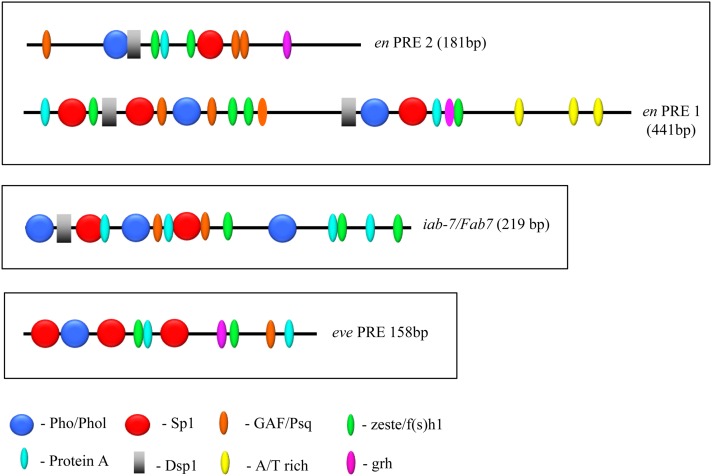

PRE architecture

PREs are made up of binding sites for many different proteins, some known and others unknown. Our detailed analysis of PRE2 suggests that at least six DNA-binding proteins, including Pho/Phol, Dsp1, Spps, GAF/Psq, Zeste/Fs(1)h, and Protein A, are required for its PSS activity. PRE1 contains presumptive binding sites for all of those proteins as well as an AT-rich region not found in PRE2. Furthermore, the spacing and order of sites differs between these two PREs (Figure 7). We examined the minimal eve and iab-7/Fab-7 PREs for the presence of these sites (Figure 7). We note that not all sites were found in the eve and iab-7/Fab-7 PREs. For example, we could not find a Dsp1 consensus sequence in the eve PRE, and Dsp1 is not bound to this locus in embryos as shown by chromatin immunoprecipitation (Schuettengruber et al. 2009). A comparison of the order and arrangement of the confirmed and putative binding sites of en PRE1, en PRE2, eve PRE, and Fab7/iab-7 PRE shows a large variation in the order and spacing of the binding sites between the different PREs. This variation may reflect critical differences that are integral to how a specific PRE functions at its endogenous locus; however, this is hard to assess given that even within a given PRE the number, order, and spacing of predicted Dsp1, Pho, GAF, and Zeste sites was found to diverge rapidly within PREs present at conserved positions in various Drosophila species (Hauenschild et al. 2008). The functional consequences of these differences have not been explored, but it does point to an overall plasticity in the system.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the order and spatial arrangement of consensus-factor-binding sites in en, eve, and iab-7/Fab7 PREs. The sequences of en PRE1 and PRE2, the minimal eve PRE [PRE300-3′ (158 bp)] (Fujioka et al. 2008), and the 219-bp iab/Fab7 PRE (Dejardin et al. 2005) were analyzed in GenePalette using the consensus sequences described in the Figure 1 legend. The distribution and order of the predicted binding sites are shown. All fragments shown mediate PSS.

This rapid evolution may result in part from redundancy in PRE activity. In the en gene, PRE1 and PRE2 are contained within a 1.6-kb region and may act together to recruit PcG complexes in their normal context. However, both of these PREs are dispensable for viability in the laboratory (Cheng et al. 2012). The en/inv gene complex has two other major PREs and a number of minor ones that can apparently take over PRE1 and PRE2 functions. This apparent redundancy in PRE activity may allow for rapid evolution and increase the diversity of these regulatory elements.

Functional differences between PREs

Both PRE1 and PRE2 mediate PSS of the mini-white gene but behave differently in the bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter complex inserted by RCME at an attP site at 52D. While both PRE1 and PRE2 could silence the bxd-Ubx-lacZ gene in salivary gland nuclei via the PcG proteins (as measured by H3K27me3 association with the lacZ gene), only PRE1 was active in embryos and larval brain. Why this difference? We suggest that PREs evolve in the context of other regulatory DNA and that, while retaining overlapping functions, they may adapt to work better with different enhancers. So, while core PRE DNA-binding proteins may remain relatively constant between PREs, some PREs may require additional factors to overcome the activity of specific enhancers.

Differences in PRE activities in transgenes have been previously described (Horard et al. 2000; Okulski et al. 2011; Park et al. 2012). In one study, multimerized subfragments of the bxd PRE showed different behaviors in a mini-white repression assay (Horard et al. 2000). In another, different PREs from the Psc/Su(z)2 complex exhibited different silencing activities on an imaginal disk reporter construct (Park et al. 2012). Both these studies were done in P-element-based vectors, and thus the activities of the reporter constructs were not examined in the same insertion sites. Since PREs are notoriously sensitive to the effects of flanking DNA, it is not easy to determine whether the differences observed were a reflection of intrinsic differences in the activity of the PREs or of the different insertion sites of the reporter genes. To avoid this problem, Okulski et al. (2011) examined the activity of a PRE from the vg gene with activity of the iab-7/Fab-7 PRE inserted in the genome at four different insertion sites via φC31 integration. This careful study showed that these two PREs exhibited different degrees of mini-white repression at different insertion sites and behaved differently with respect to PSS at the same insertion sites. The problem with this study was that the investigators used relatively large fragments of DNA (1.6 kb). Thus it is likely that other regulatory sequences were contained within the PRE fragments, and it is not known how additional regulatory sequences modify PRE activity. Even in the 181-bp DNA fragment that we call PRE2, there is another regulatory activity, a promoter-tethering element, which may affect its ability to act as a PRE in some chromosomal locations (Kwon et al. 2009). In previous studies from our group, when a 2.6-kb piece of en DNA that included PRE1 and PRE2 and flanking DNA was included in a bxd-Ubx-lacZ P-element-based transgene, the en fragment almost completely silenced the entire lacZ expression pattern in embryos (Americo et al. 2002). We suspect that regulatory DNA within that fragment was able to silence the bxd enhancer and that this activity might be separable from the PRE activity per se.

Concluding remarks

From this work and the work of many others we conclude that PREs are a diverse group of related elements that have overlapping but not identical activities. PREs vary in both size and binding-site composition requiring a number of different DNA-binding proteins to function collaboratively to recruit PcG complexes and introduce repressive histone modifications. The diverse PRE architecture could influence exactly which PcG protein complexes are recruited and what types of enhancers they are able to silence or repress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miki Fujioka for the bxd-Ubx-lacZ RCME vector and for transgenic lines; Bill McGinnis for the generous gift of Grh antibodies; and Emma Hornick for construction of the bxd-Ubx-lacZ reporter constructs. We also thank Yuzhong Cheng, Payal Ray, and Sandip De for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: P. K. Geyer

Literature Cited

- Almeida M. S., Bray S. J., 2005. Regulation of post-embryonic neuroblasts by Drosophila Grainy head. Mech. Dev. 122: 1282–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Americo J., Whiteley M., Brown J. L., Fujioka M., Jaynes J. B., et al. , 2002. A complex array of DNA-binding proteins required for pairing-sensitive silencing by a Polycomb group response element from the Drosophila engrailed gene. Genetics 160: 1561–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman J. R., Lee A. M., Wu C.-T., 2006. Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via φC31 Integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics 173: 769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson M., Pirrotta V., 1988. The Drosophila zeste protein binds cooperatively to sites in many gene regulatory regions: implications for transvection and gene regulation. EMBO J. 7: 3907–3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blastyák A., Mishra R. K., Karch F., Gyurkovics H., 2006. Efficient and specific targeting of Polycomb group proteins requires cooperative interaction between Grainy head and Pleiohomeotic. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 1434–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. L., Kassis J. A., 2010. Spps, a Drosophila Sp1/KLF family member binds to PREs and is required for PRE activity late in development. Development 137: 2597–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. L., Mucci D., Whiteley M., Dirksen M. L., Kassis J. A., 1998. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene pleiohomeotic encodes a DNA binding protein with homology to the transcription factor YY1. Mol. Cell 1: 1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. L., Fritsch C., Müller J., Kassis J. A., 2003. The Drosophila pho-like gene encodes a YY1-related DNA binding protein that is redundant with pleiohomeotic in homeotic gene silencing. Development 130: 285–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. L., Grau D. J., DeVido S. K., Kassis J. A., 2005. An Sp1/KLF binding site is important for the activity of a Polycomb group response element from the Drosophila engrailed gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 5181–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busturia A., Lloyd A., Bejarano F., Zavortink M., Xin H., et al. , 2001. The MCP silencer of the Drosophila Abd-B gene requires both Pleiohomeotic and GAGA factor for the maintenance of repression. Development 128: 2163–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R., Wang L., Wang H., Xia L., Erdjument-Bromage H., et al. , 2002. Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science 298: 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. L., King B., Lin S. C., Kennison J. A., Huang D. H., 2007. A double-bromodomain protein, FSH-S, activates the homeotic gene Ultrabithorax through a critical promoter-proximal region. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 5486–5489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Kwon D. Y., Arai A. L., Mucci D., Kassis J. A., 2012. P-element homing is facilitated by engrailed polycomb-group response elements in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 7: e30437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M. D., Brown J. L., Kassis J. A., 2010. Characterization of the Polycomb group response elements of the Drosophila melanogaster invected locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30: 820–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czermin B., Melfi R., McCabe D., Seitz V., Imhof A., et al. , 2002. Drosophila enhancer of Zeste/ESC complexes have a histone H3 methyltransferase activity that marks chromosomal Polycomb sites. Cell 111: 185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decoville M., Giacomello E., Leng M., Locker D., 2001. DSP1, an HMG-like protein, is involved in the regulation of homeotic genes. Genetics 157: 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin J., Cavalli G., 2004. Chromatin inheritance upon Zeste-mediated Brahma recruitment at a minimal cellular memory module. EMBO J. 23: 857–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejardin J., Rappailles A., Cuvier O., Grimaud C., Decoville M., et al. , 2005. Recruitment of Drosophila Polycomb group proteins to chromatin by DSP1. Nature 434: 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellino G. I., Tatout C., Pirrotta V., 2002. Extensive conservation of sequences and chromatin structures in the bxd Polycomb Response Element among Drosophilid species. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46: 133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVido S. K., Kwon D., Brown J. L., Kassis J. A., 2008. The role of Polycomb-group response elements in regulation of engrailed transcription in Drosophila. Development 135: 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler T., Rehmsmeier M., 2006. jPREdictor: a versatile tool for the prediction of cis-regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: W546–W550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch C., Brown J. L., Kassis J. A., Müller J., 1999. The DNA-binding Polycomb group protein Pleiohomeotic mediates silencing of a Drosophila homeotic gene. Development 126: 3905–3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch C., Beuchle D., Müller J., 2003. Molecular and genetic analysis of the Polycomb group gene sex combs extra/Ring in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 120: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka M., Yusibova G. L., Zhou J., Jaynes J. B., 2008. The DNA-binding Polycomb-group protein Pleiohomeotic maintains both active and repressed transcriptional states through a single site. Development 135: 4131–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieni R. S., Hendzel M. J., 2009. Polycomb group protein gene silencing, non-coding RNA, stem cells, and cancer. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87: 711–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm C., Matos R., Ly-Hartig N., Stuerwald U., Lindner D., et al. , 2009. Molecular recognition of histone lysine methylation by the Polycomb group repressor dSfmbt. EMBO J. 28: 1965–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth A. C., Fish M., Nusse R., Calos M. P., 2004. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage φC31 integrases. Genetics 166: 1775–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom K., Müller M., Schedl P., 1997. A Polycomb and GAGA dependent silencer adjoins the Fab-7 boundary in the Drosophila bithorax complex. Genetics 146: 1365–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenschild A., Ringrose L., Altmutter C., Paro R., Rehmsmeier M., 2008. Evolutionary plasticity of Polycomb/Trithorax response elements in Drosophila species. PLoS Biol. 6: e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horard B., Tatout C., Poux S., Pirrotta V., 2000. Structure of a polycomb response element and in vitro binding of Polycomb group complexes containing GAGA factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 3187–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur M. W., Laney J. D., Jeon S. H., Ali J., Biggin M. D., 2002. Zeste maintains repression of Ubx transgenes: support for a new model of Polycomb repression. Dev. 129: 1339–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis J. A., 1994. Unusual properties of regulatory DNA from the Drosophila engrailed gene: three “pairing-sensitive” sites within a 1.6-kb region. Genetics 136: 1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis J. A., 2002. Pairing-sensitive silencing, Polycomb group response elements, and transposon homing in Drosophila. Adv. Genet. 46: 421–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis J. A., Brown J. L., 2013. Polycomb group response elements in Drosophila and vertebrates. Adv. Genet. 83: 83–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis J. A., Desplan C., Wright D. K., O’Farrell P. H., 1989. Evolutionary conservation of homeodomain-binding sites and other sequences upstream and within the major transcription unit of the Drosophila segmentation gene engrailed. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9: 4304–4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassis J. A., Vansickle E. P., Sensabough S. M., 1991. A fragment of engrailed regulatory DNA can mediate transvection of the white gene in Drosophila. Genetics 128: 751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola T. K., 2009. Polycomb group complexes: many combinations, many functions. Trends Cell Biol. 19: 692–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymenko T., Papp B., Fischle W., Kocher T., Schelder M., et al. , 2006. A Polycomb group protein complex with sequence-specific DNA-binding and selective methyl-lysine-binding activities. Genes Dev. 20: 1110–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., McGinnis W., 2011. Phosphorylation of Grainy head by ERK is essential for wound-dependent regeneration of an epidermal barrier but dispensable for embryonic barrier development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 650–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon D., Mucci D., Langlais K., Americo J. L., DeVido S. K., et al. , 2009. Enhancer-promoter communication at the Drosophila engrailed locus. Development 136: 3067–3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong C., Adryan B., Bell I., Meadows L., Russell S., et al. , 2008. Stability and dynamics of Polycomb target sites in Drosophila development. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarou A., Mohd-Sarip A., Moshkin Y. M., Chalkley G. E., Bezatarosti K., et al. , 2008. dKDM2 couples histone H2A ubiquitination to histone H3 demethylation during Polycomb group silencing. Genes Dev. 22: 2799–2810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R. K., Mihaly J., Barges S., Spierer A., Karch F., et al. , 2001. The iab-7 Polycomb response element maps to a nucleosome-free region of chromatin and requires both GAGA and Pleiohomeotic for silencing activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 1311–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed D., O’Farrell P. H., 1992. Maintenance of the engrailed expression pattern by Polycomb group genes in Drosophila. Development 116: 805–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Sarip A., Venturini F., Chalkley G. E., Verrijzer C. P., 2002. Pleiohomeotic can link Polycomb to DNA and mediate transcriptional repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 7473–7483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Sarip A., Cleard F., Mishra R. K., Karch F., Verrijzer C. P., 2005. Synergistic recognition of an epigenetic DNA element by Pleiohomeotic and a Polycomb core complex. Genes Dev. 19: 1755–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd-Sarip A., Van der Knaap J. A., Wyman C., Kanaar R., Schedl P., et al. , 2006. Architecture of a polycomb nucleoprotein complex. Mol. Cell 24: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann L., Kal A. J., Verrijzer C. P., 2002. Characterization of the extended Myb-like DNA-binding domain of trithorax group protein Zeste. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 47385–47392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses A. M., Pollard D. A., Nix D. A., Iyer V. N., Li X.-Y., et al. , 2006. Large-scale turnover of functional transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2: e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland N. M., King I. F., Kingston R. E., 2003. Regulation of Polycomb group complexes by the sequence-specific DNA binding proteins zeste and GAGA. Genes Dev. 17: 2741–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Bienz M., 1991. Long range repression conferring boundaries of Ultrabithorax expression in the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 10: 3147–3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Kassis J. A., 2006. Polycomb response elements and targeting of Polycomb group proteins in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16: 476–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Verrijzer C. P., 2009. Biochemical mechanisms of gene regulation by Polycomb group protein complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19: 150–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J., Hart C. M., Francis N. J., Vargas M. L., Sengupta A., et al. , 2002. Histone methyl transferase activity of a Drosophila Polycomb group repressor complex. Cell 111: 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negre N., Hennetin J., Sun L. V., Lavrov S., Bellis M., et al. , 2006. Chromosomal distribution of PcG proteins during Drosophila development. PLoS Biol. 4: 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov M., Klymenko T., Fraterman S., Papp B., Oktaba K., et al. , 2007. Pcl-PRC2 is needed to generate high levels of H3–K27 trimethylation at Polycomb target genes. EMBO J. 26: 4078–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktaba K., Gutierrez L., Gagneur J., Girardot C., Sengupta A. K., et al. , 2008. Dynamic regulation of polycomb group protein complexes controls pattern formation and the cell cycle in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 15: 877–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okulski H., Druck B., Bhalerao S., Ringrose L., 2011. Quantitative analysis of Polycomb response elements (PREs) at identical genomic locations distinguishes contributions of PRE sequence and genomic environment. Epigenetics Chromatin 4: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Schwartz Y. B., Kahn T. G., Asker D., Pirrotta V., 2012. Regulation of Polycomb group genes Psc and Su(z)2 in Drosophila melanogaster. Mech. Dev. 128: 536–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrotta V., 1988. Vectors for P-mediated transformations in Drosophila, pp. 437–456 in Vectors: A Survey of Molecular Cloning Vectors and Their Uses, edited by Rodriguez R. L., Denhardt D. T. Butterworths, Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz M., Posakony J. W., 2004. GenePalette: an unusual software tool for genome sequence visualization and analysis. Dev. Biol. 15: 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose L., Rehmsmeier M., Dura J. M., Paro R., 2003. Genome-wide prediction of Polycomb/Trithorax response elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Cell 5: 759–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurin A. J., Shao Z., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Kingston R. E., 2001. A Drosophila Polycomb group complex includes Zeste and dTAFII proteins. Nature 412: 655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuermann J. C., Alonso A. G., Oktaba K., Ly-Hartig N., McGinty R. K., et al. , 2010. Histone H2A deubiquitinase activity of the Polycomb repressive complex PR-DUB. Nature 465: 243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettengruber B., Chourrout D., Veroort M., Leblanc B., Cavalli G., 2007. Genome regulation by polycomb abd trithorax proteins. Cell 128: 735–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettengruber B., Ganapathi M., Leblanc B., Portoso M., Jaschek R., et al. , 2009. Functional anatomy of polycomb and trithorax chromatin landscapes in Drosophila embryos. PLoS Biol. 7: 0001–0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz Y. B., Kahn T. G., Nix D. A., Li X. Y., Bourgon R., et al. , 2006. Genome-wide analysis of Polycomb targets in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 38: 700–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z., Raible F., Mollaaghababa R., Guyon J. R., Wu C. T., et al. , 1999. Stabilization of chromatin structure by PRC1, a Polycomb complex. Cell 98: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields J. M., Yang V. W., 1998. Identification of the DNA sequence that interacts with the gut-enriched Krüppel-like factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 796–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimell M. J., Peterson A. J., Burr J., Simon J. A., O’Connor M. B., 2000. Functional analysis of repressor binding sites in the iab-2 regulatory region of the abdominal-A homeotic gene. Dev. Biol. 218: 38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J. A., Kingston R. E., 2009. Mechanisms of Polycomb gene silencing: knowns and unknowns. Nat. Rev. Biol. 10: 697–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J., Chiang A., Bender W., Shimell M. J., O’Connor M., 1993. Elements of the Drosophila bithorax complex that mediate repression by Polycomb group products. Dev. Biol. 158: 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhuis B., de Wit E., Muijrers I., Teunissen H., Talhout W., et al. 2006. Genome-wide profiling of PRC1 and PRC2 Polycomb chromatin binding in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 38: 694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckfield A., Clouston D. R., Wilanowski T. M., Zhao L. L., Cunningham J. M., et al. , 2002. Binding of the RING Polycomb proteins to specific target genes in a complex with the Grainy head-like family of developmental transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 1936–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan K., McManus H. R., Mello C. C., Smith T. F., Hansen U., 2003. Functional conservation between members of an ancient duplicated transcription factor family, LSF/Grainy head. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 4304–4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wang L., H. Erdjument-Bromage, M. Vidal, P. Tempst et al, 2004. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature 431: 873–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Jahren N., Miller E. L., Ketel C. S., Mallin D. R., et al. , 2010. Comparative analysis of chromatin binding by sex comb on midleg (SCM) and other Polycomb group repressors at a Drosophila Hox gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30: 2584–2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]