Abstract

Insulin and target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathways converge to maintain growth so a proportionate body form is attained. Insufficiency in either insulin or TOR results in developmental growth defects due to low ATP level. Spargel is the Drosophila homolog of PGC-1, which is an omnipotent transcriptional coactivator in mammals. Like its mammalian counterpart, Spargel/dPGC-1 is recognized for its role in energy metabolism through mitochondrial biogenesis. An earlier study demonstrated that Spargel/dPGC-1 is involved in the insulin–TOR signaling, but a comprehensive analysis is needed to understand exactly which step of this pathway Spargel/PGC-1 is essential. Using genetic epistasis analysis, we demonstrated that a Spargel gain of function can overcome the TOR and S6K mediated cell size and cell growth defects in a cell autonomous manner. Moreover, the tissue-restricted phenotypes of TOR and S6k mutants are rescued by Spargel overexpression. We have further elucidated that Spargel gain of function sets back the mitochondrial numbers in growth-limited TOR mutant cell clones, which suggests a possible mechanism for Spargel action on cells and tissue to attain normal size. Finally, excess Spargel can ameliorate the negative effect of FoxO overexpression only to a limited extent, which suggests that Spargel does not share all of the FoxO functions and consequently cannot significantly rescue the FoxO phenotypes. Together, our observation established that Spargel/dPGC-1 is indeed a terminal effector in the insulin–TOR pathway operating below TOR, S6K, Tsc, and FoxO. This led us to conclude that Spargel should be incorporated as a new member of this growth-signaling pathway.

Keywords: PGC-1, Spargel, cell growth, Drosophila, insulin signaling

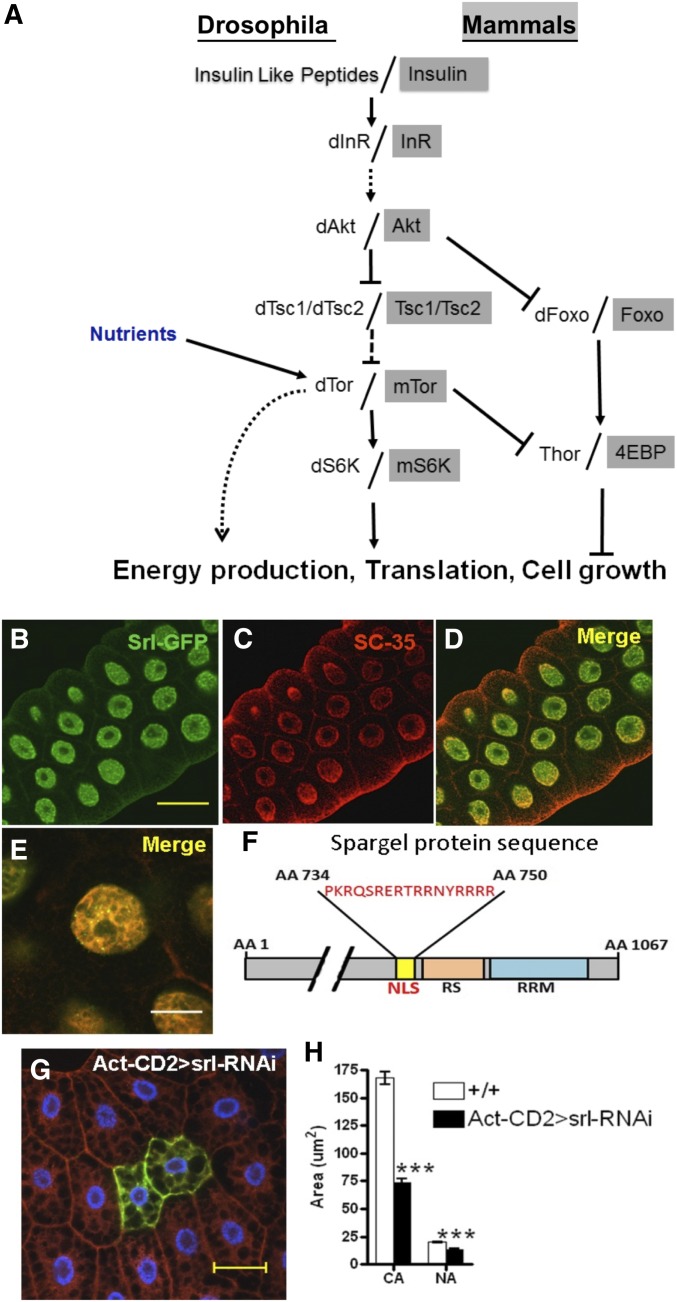

TO attain proper cellular growth, availability of nutrients is imperative, because the nutrient supply fuels energy metabolism. Thus lack of nourishment cause limited growth of the organism due to reduced energy metabolism (Hietakangas and Cohen 2009; DePalma et al. 2012). Sensing and transport of growth signals happen in two distinct pathways: at the cellular level, the TOR pathway governs growth (Saltiel and Kahn 2001; Grewal 2009), whereas insulin signaling is responsible for subsequent adjustment of the cellular metabolism causing growth at a more systemic level. Ultimate convergence of these two signaling pathways leads to balanced growth. Therefore each member of the insulin–TOR pathway has recognized influence on cell size and cell growth as demonstrated either in cell clones or at the whole organism level. Severe growth defect during prenatal development such as intrauterine growth restriction and low birth weight have been linked to paucity of insulin–Tor signaling (Murakami et al. 2004; Gannage-Yared et al. 2012) and ATP production (Selak et al. 2003). Like in most animals, the insulin–TOR signaling pathway in Drosophila is dedicated to the control of growth and metabolism (Figure 1A). With its enriched genetic and genomic resources, flies have contributed significantly toward the understanding of nutritional physiology and cell growth control (Hietakangas and Cohen 2009).

Figure 1.

Cellular localization of Spargel follows PGC-1. (A) Schematic representation of the insulin–TOR signaling pathway: insulin and TOR signaling pathway acts together to control growth in Drosophila and mammals. The insulin-like growth factors/insulin turns on this pathway, depending on the availability of glucose in the system. Details of insulin signaling have been reviewed elsewhere (Bier 2005; Grewal 2009). TOR plays a central role in regulating cell growth and control of mitochondrial energy. Each member of this pathway can control cell growth in a cell autonomous manner (Hennig et al. 2006). (B) GFP–Spargel fusion protein is localized exclusively inside the nucleus where it is not homogenously distributed; instead Spargel appears in the form of punctate structures. (C and D) Pre-mRNA splicing factor SC-35 (red), which is localized exclusively inside the nucleus in the form of nuclear speckles, colocalized with Spargel (merge) in many of these puntae. Bar, 40 μm. (E) At higher magnification (Bar, 20 μm) Spargel (green) and SC-35 (red) merge appears as yellow signals. As shown here inside a polytene nucleus, Spargel and SC35 are quite intimately associated, indicating a conserved role of PGC-1 and Spargel in the splicing complex. (F) Spargel carries a 16-amino-acid nuclear localization signal (NLS) as predicted by PredictProtein and NLS Mapper software. (G) Cells expressing spargel RNAi (two GFP positive cells) appeared much smaller in size, suggesting that like all other insulin family members Spargel functions in cell growth in a cell autonomous manner. (H) Quantification of cell size confirmed that both the cytoplasmic area (CA) and nuclear area (NA) were reduced in spargel RNAi cell clones as compared to the control (non-GFP cells). Bar, 40 μm. N, number of cell clones counted >25. ***P < 0.001.

Peroxysome proliferator-activating receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PGC-1) is a key transcriptional coactivator in mammals, which is involved in energy homeostasis (Lin et al. 2005), gluconeogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, regulation of thermal tolerance, and a more recent report suggests that PGC-1 is capable of responding to environmental cues, such as nutrients (Bhalla et al. 2011). The single Drosophila PGC-1 homolog is designated as Spargel (Tiefenbock et al. 2010), which shares significant homology with PGC-1 at the RNA recognition motif (RRM) and serine–arginine repeat (RS) (Gershman et al. 2007). Previous observation claimed that Spargel functions in the insulin signaling pathway because reduced Spargel expression abrogates the cellular overgrowth resulting from overexpression (OE) of insulin receptor (InR) (Tiefenbock et al. 2010) because Spargel acts downstream to InR. In mammalian hepatocytes, PGC-1 is known to act in the TOR pathway (Cunningham et al. 2007; Lustig et al. 2011), although how PGC-1 is related to growth remains undefined. An important first question remains: Where in the insulin–TOR signaling pathway is Spargel action required? We pursue this question with the help of genetic epistasis analysis.

Insulin–TOR signaling is central to cell growth and cell size determination, hence the loss of function of some of its members and gain of function of the others, all influencing the cell size as demonstrated either at the whole organism level or in cell clones (Hietakangas and Cohen 2009). Taking advantage of their effect on cell size, we tested the action of spargel hypomorph and/or Spargel gain of function on TOR, S6K, Tsc, and FoxO-induced cell growth defects. If Spargel functions downstream of any of these then Spargel overexpression should rescue or at least amend TOR, S6K, Tsc, and FoxO mutants’ effect on cell size, whereas, a nonrescue will mean Spargel action is required upstream.

Materials and Methods

Stocks

UAS-srl+-, Tsc2RNAi-, and FoxO-null flies were obtained from the Christian Frei, Morris Birnbaum, and Linda Partridge laboratories respectively. Act-GAL4, ap-GAL4, MS1096-GAL4, EP-srl+, UAS-TORTED, UAS-S6kSTDETE, UAS-S6kKQ, Act-CD2>GAL4, hsp-FLP: UAS-GFP, UAS-FoxO, GMR-GAL4, and UAS-srl RNAi fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Fly cultures were maintained in standard media at 23 ± 1° temperature. Transgenic expression of GFP–Spargel fusion protein was achieved by cloning the spargel cDNA into UASP–Gateway vector with N-terminal GFP.

Somatic clones and immunocytochemistry

Clones were generated in fat body cells by adopting the FLP-out technique (Zhang et al. 2006). Individual UAS lines were crossed with hsp-FLP UAS-GFP; Act > CD2 > GAL4 flies, so clones were formed ubiquitously in the F1 progenies. Fat body tissue obtained from the F1 larvae were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/1× PBS/0.2% Triton-X 100. For phalloidin staining, fat bodies were permeabilized with 0.3% TX-100 in 1× PBS for 10 min and incubated for 2 hr in 1 μM rhodamine-tagged phalloidin at room temperature. Fat bodies were washed, mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Lab), and visualized under confocal microscope (Nikon).

Antibody

Phospho-4EBP (1:200) and Phospho-S6K (1:200) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Miron et al. 2003). Antiactin (1:5000) antibody was obtained from Abcam.

Direct mitochondria visualization

Fat bodies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 20 mM formic acid. ATP5A (1: 250) (MitoSciences) antibody was used to detect mitochondria (Cox and Spradling 2009).

Microscopy

Visualization and analysis of the clones were done using a Nikon (EZ-C1) confocal microscope. Measurement of clone size and mitochondrial fluorescence intensity quantitation was done with Nikon NIS-Element software.

RT–PCR

RNA extraction was done using Qiagen RNeasy spin kit (catalog no.74104). Thirty-five flies were homogenized in 250 μl of buffer RLT with β-marcaptoethanol. Homogenate was centrifuged at full speed for 10 min at 4°. The supernatant was added to the g-DNA spin column and centrifuged for 1 min at 11,000 rpm. The flow through was mixed with equal volume of 70% ethanol and added to the RNAeasy spin column. After centrifugation, 700 μl of buffer RW1 was added to the column and centrifuged for 1 min at 11,000 rpm. 500 μl of buffer RPE was added, centrifuged, and the step was repeated. The columns were added in a new tube and centrifuged for 1 min at full speed. The columns were transferred to a new tube, 35 μl of RNase-free water was added, and centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 1 min. Collected RNA was quantified and 2 μg of RNA was used to make the cDNA.

Western blot

Total protein was isolated by homogenization of ∼30 flies in a prechilled extraction buffer (10 mM DTT, 4% glycerol, and 0.15 M Tris-Cl pH 7.5). Homogenates were spun down at 14,000 rpm for 10 min in 4°. Supernatant was collected and protein concentration was adjusted using the Bio-Rad quick start Bradford assay. Protein samples were denatured by boiling and were then electrophoresed (2 μg/μl) on an SDS–PAGE (14% denaturing and 4% stacking gel) at 120 V for 1 hr at room temperature. Samples were run simultaneously alongside a protein standard (BioRad Precision Plus 250, 10 kDa). Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to Millipore’s Immobilion-PSQ (0.2 m pore size) PVDF membrane for 60 min in cold (4°) at 120 V. The PVDF membrane was then blocked with 5% fat-free milk dissolved in 1× TTBS (100 mM Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 0.9% NaCl and 0.1% v/v Tween 20) overnight in 4°. The membrane was washed twice (5 min each) with 1× TTBS and probed with primary antibody (1 μl Ab in 5 ml TTBS containing 1% fat-free milk) for 1 hr. Excess primary antibody was washed off by rinsing three times (5 min each) with 1× TTBS. The membrane was then incubated in secondary antibody (1 μl Ab in 5 ml TTBS containing 1% fat-free skimmed milk) for 1 hr, and then rinsed three times with 1× TTBS. Lastly for detection, ∼4 ml of ECL was added (Amersham Biosciences) per blot. To test the phosphorylation status of S6k and 4EBP, anti-S6k antibody (1:500) (Cell Signaling) and anti-4EBP (1:500) (Cell Signaling) antibodies were used.

Statistics and software

Measured cellular and nuclear areas were compared using Student’s t-test. Significance of pupal and adult rescues was determined using the chi-square test. Nuclear localization signal (NLS) in Spargel was predicted using two independent software programs, PredictProtein (http://www.predictprotein.org/) and NLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) under high stringency. The possibility of Spargel localization in the nucleus was checked with two different software programs, NucPred (http://www.sbc.su.se/~maccallr/nucpred/) and ESLPred (http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/eslpred/).

Results and Discussion

Subcellular localization of Spargel and PGC-1 is comparable

Significant structural homologies exist between Spargel and PGC-1 (Gershman et al. 2007). We noticed with interest that these two molecules share a comparable subcellular localization, which may have some greater functional significance. Ubiquitous expression of a GFP-tagged Spargel protein with Act-GAL4 driver displayed that Spargel is localized exclusively within the nucleus (Figure 1B), the same as PGC-1, which is largely located in the nucleus (Monsalve et al. 2000). Interestingly, Spargel localization in the nucleus is predictable with Nucpred and ESLpred software (Bhasin and Raghava 2004; Brameier et al. 2007) with almost 93–94% accuracy. Nuclear localization of Spargel was further confirmed with a specific nuclear protein SC35, a pre-mRNA splicing factor (Fu and Maniatis 1992) (Figure 1C). In mammalian cells, PGC-1 has been shown to be associated with the splicing complexes because PGC-1 and SC35 are colocalized to the same punctate structures (Monsalve et al. 2000). To test whether Spargel maintains a similar characteristic, we found that Spargel and SC35 are also colocalized to the same speckles almost perfectly (Figure 1D). Under higher magnification, salivary gland polytene nuclei displayed more intimate association between SC35 and Spragel (Figure 1E, yellow signals), which help us to predict that both Spargel and PGC-1 are conserved constituents of the splicing complex. We believe that such discrete localization of Spargel into the nucleus is possibly resulting from an embedded 16-amino-acid-long Nuclear Localization signal (NLS) (amino acids 734–750) as predicted by PredictProtein and NLS Mapper software (Rost and Liu 2003; Kosugi et al. 2009) (Figure 1F). Contrary to our observation, an earlier study claimed that a HA-tagged Spargel protein is localized in the cytoplasmic compartment, which gets transported inside the nucleus following activation by insulin receptor (Tiefenbock et al. 2010). Based on colocalization data and other characteristics, nuclear localization of Spargel appears to be more logical; however, future studies should be able to resolve this issue further.

Spargel acts downstream of TOR and S6kinase:

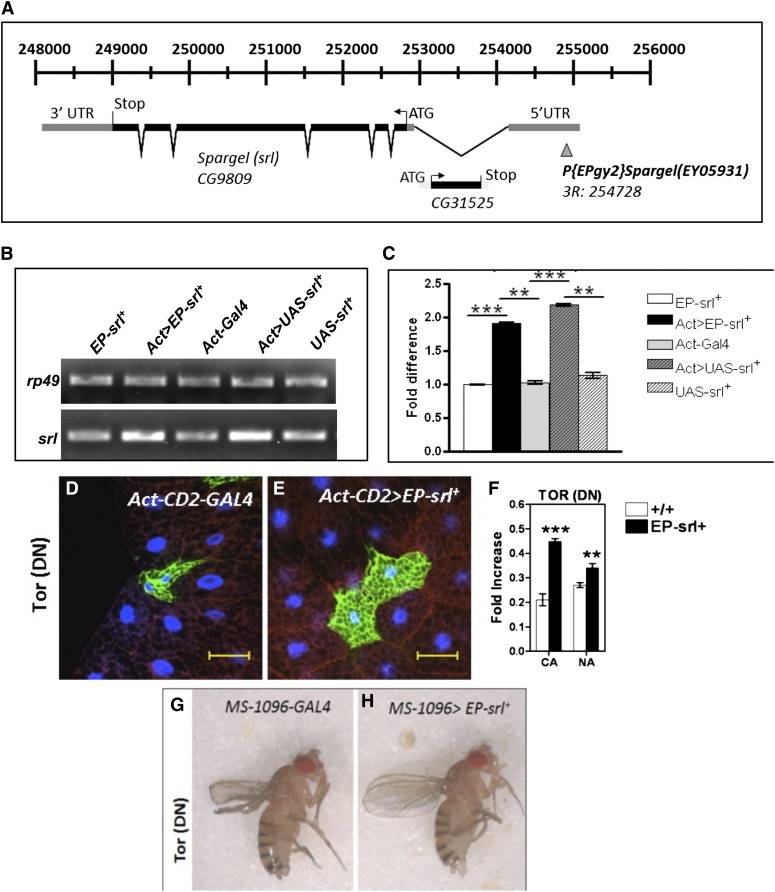

TOR is at the core of cell and tissue growth as TOR can influence cell growth in a cell autonomous manner (Wullschleger et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006). Absence of the TOR nutrient sensor causes smaller cell size and fully penetrant larval lethality (Zhang et al. 2000; Hennig et al. 2006). We wanted to test the interaction between TOR and Spargel on cell growth because many of TOR’s diverse effects on cellular physiology overlap with Spargel (Zhang et al. 2000; Schieke et al. 2006). For example, clones of cells with reduced Spargel expression appear smaller in size (Figure 1, G and H) and spargel hypomorphic adults have smaller body size (Supporting Information, Figure S1E). This led us to conclude that Spargel can control cell growth in a cell autonomous manner similar to TOR.

Cell clones expressing TOR-dominant negative [TOR(DN)] mutation (Hennig and Neufeld 2002) (also known as TOR toxic effector domain, TORTED) appeared much smaller in size due to reduced cell growth (Figure 2D). TORTED expresses the 754-amino-acid central domain of TOR that acts in a dominant negative fashion because it is thought to sequester signaling factors. Overexpression of Spargel protein (Figure 2, A–C) in the TOR(DN) cells helps ∼80% of the small-sized TOR(DN) cell to attain normal size (Figure 2, E and F). This led us to wonder whether Spargel is a downstream mediator of TOR-induced cell growth. So, we attempted to restore the tissue-restricted phenotypes of TOR(DN) with Spargel. When expressed in the wings with wing-specific MS-1096-GAL4 driver, TOR(DN) causes a wing defect (Figure 2G) due to severe restriction of cell growth during wing development (Hennig and Neufeld 2002). Co-overexpression of Spargel and TOR(DN) with the same GAL4 driver suppresses the wing phenotype and results in a completely normal wing shape (Figure 2H). As a final attempt, we wanted to rescue the lethal effect of TOR(DN) with excess Spargel. TOR(DN) is early lethal (Hennig and Neufeld 2002) so no pupae are recovered in this mutant (Table S1) (Hennig and Neufeld 2002). Ubiquitous overexpression of Spargel with the help of Act-GAL4 driver in the TOR(DN) embryos resulted in 94% pupal formation of which 10–12% actually eclosed as adults, which is unprecedented (Table S1). Spargel-rescued TOR(DN) adults still appeared smaller in body size (Figure S1D) and they survived for a brief length of time. These data imply that Spargel can only take over certain functions of TOR, such as cell growth control, as documented. Yet TOR also controls a large array of cellular processes (DePalma et al. 2012; Laplante and Sabatini 2012) and given that the rescue was not complete, we interpret the result to indicate that Spargel does not function in all the effects mediated by TOR. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that Spargel overexpression does not influence the phosphorylation status of 4EBP (Figure S2), meaning TOR regulates 4EBP phosphorylation in a Spargel-independent manner. We therefore conclude that TOR’s action on cell size and cell growth is mediated through Spargel and thus Spargel is an important downstream effector of TOR for cell growth signaling.

Figure 2.

Spargel is downstream of Tor. (A) Spragel overexpression (OE) was achieved by activating an EP(gy2) insertion in the 5′-UTR of spargel (CG9809) with a Act-GAL4 driver. (B and C) RT–PCR analysis of spargelOE with EP(gy2)srl+ and UAS-srl+ insertions with Act-GAL4 driver confirmed that the EP-srl+ element overexpresses Spargel at the same level as the UAS-srl+. About twofold more spargel mRNA expression was achieved from both EP and UAS lines. Since EP-srl+ is located on the third chromosome, and UAS-srl+ is located on the second, the former insertion was chosen since it makes the genetic manipulations easier. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. (D) Cells expressing TOR(DN) (two GFP-positive cells) mutation in the fat body tissue appeared much smaller in size with tiny nuclei (blue). (E) Spargel OE helps to recover the reduced cell size of TOR(DN) cell clones (GFP positive), which now appears normal in size. (F) Comparison of the nuclear area (NA) and cytoplasmic area (CA) of TOR(DN) cell clones before and after Spargel OE confirmed that a significant increase in cell size occurs following Spargel OE (N > 25). Bar, 40 μm. CA, cytoplasmic area normalized with control; NA, nuclear area normalized with control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (G) Expression of TOR(DN) in the wings with MS-1094-GAL4 causes shortened and misshaped wings due to cell growth defect. (H) Following Spargel OE, the wings of TOR(DN) attained their normal shape and size (N > 25).

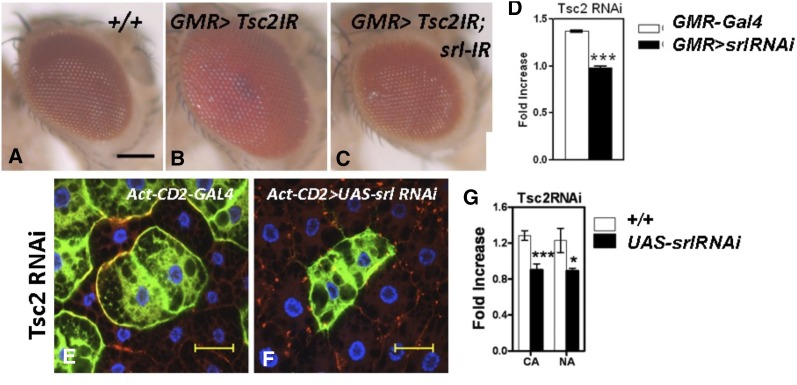

The above conclusion will be best supported if spargel-RNAi can block the TOR overexpression phenotype. Since TOR overexpression is lethal, we used the tuberous sclerosis complex (Tsc), which works upstream of TOR and negatively regulates TOR function (DePalma et al. 2012). Thus inactivation of Tsc2 through RNAi (also known as gigas-RNAi) in the eye tissue causes an eye enlargement effect (Figure 3, A and B), the same as Tsc2 mutants (Potter et al. 2001). When Spargel levels are reduced (with spargel RNAi) in conjunction with Tsc-2 RNAi, this double mutant has the same phenotype as that of spargel-RNAi because the excess cell growth defect of Tsc-2 was abrogated, causing the eyes to attain their normal shape (Figure 3, C and D). Similarly, the overgrowth phenotype of the Tsc2 RNAi cell clones (Figure 3E) in the fat body tissue are suppressed by spargel RNAi (Figure 3, F and G) with ∼80% efficiency. These data suggest that Spargel action is necessary for Tsc-2 to impose its effect on cell growth and most importantly provide further support that loss of Spargel can counteract the high TOR activity that is already known to be induced by the loss of Tsc.

Figure 3.

Reduced Spargel expression suppresses the Tsc2 RNAi-mediated overgrowth. (A) Normal eye. (B) Activation of Tsc2-RNAi in the eye with GMR-GAL4 causes cellular overgrowth so the eyes appear much larger in size. (C) The overgrowth effect of Tsc-2 reduction is mended when spargel expression is reduced with spargel RNAi so the eyes turned normal (N > 25). (D) Tsc-2RNAi effect and cosuppression of Tsc-2; spargel was normalized with control eye. Bar for eye, 100 px. (E) Tsc2 RNAi expression in cell clones (GFP positive) causes over growth of those cells (compare with non-GFP cells). (F and G) Activation of spargel RNAi in Tsc-2RNAi cell clones ameliorates the overgrowth phenotype. Bar for cell clones, 40 μm. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

S6 kinase (S6K), is primarily involved in cellular protein synthesis (Ruvinsky and Meyuhas 2006) and it is the immediate downstream effector of TOR (Figure 1A). Overexpression of S6K causes cellular overgrowth and such overgrowth phenotype can be normalized by down-regulating Spargel expression in these cells (Figure 4, A and B). On the other hand, due to reduced protein synthesis, S6K(DN) (also known as S6KKQ; lysine (K109) is replaced by glutamine generates kinase dead S6K protein) cells appear much smaller in size (Barcelo and Stewart 2002) (Figure 4D) and for the same reason S6k mutants have growth defects with smaller body size and high frequency of larval lethality (Montagne et al. 1999). Clonally expressed excess Spargel allowed 100% of the S6k(DN) cells in the clones to attain normal cell size (Figure 4E). S6k(DN) expression on the dorsal surface of the wing with an apterous-GAL4 driver causes the wings to bend upwards due to cell size reduction on the dorsal wing surface (Figure 4G). Overexpression of Spargel with the same apterous-GAL4 helps this bent wing phenotype to return to its normal shape and size (Figure 4H), suggesting that Spargel acts downstream, hence its overexpression is rescuing the S6K phenotype. Phosphorylation of S6K by TOR-kinase activates the S6K pathway leading to downstream protein synthesis. We therefore investigated whether Spargel overexpression changes the phosphorylation status of S6K. We did not see a change in S6K phosphorylation (Figure S2), which further supports our interpretation that Spargel acts downstream of S6K in the insulin–TOR pathway. To summarize, in the insulin–TOR pathway Spargel is a downstream effector of TOR and S6K to inflict its effect on cell size regulation.

Figure 4.

Spargel acts downstream to S6Kinase. (A) S6K gain of function in the fat body cells (GFP positive) cause cellular overgrowth. (B and C) Following spargel RNAi, the S6K overexpressing cells attained regular size (N > 25). (D) Cells carrying the S6k(DN) mutation negatively affects cell growth so they appeared much smaller in size. (E and F) Effect of S6k(DN) on cell size can be completely (100%) rescued with excess Spargel as evident from immunohistochemistry and comparison of NA and CA measurement (N > 25). Bar, 40 μm. CA, cytoplasmic area normalized with control; NA, nuclear area normalized with control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (G) Expression of S6k(DN) on the dorsal surface of the wing with apterous-GAL4 causes the wings to bend upward. (H) Near complete rescue of the S6k(DN) wing defects was possible when Spargel is overexpressed in the same wings (N > 25).

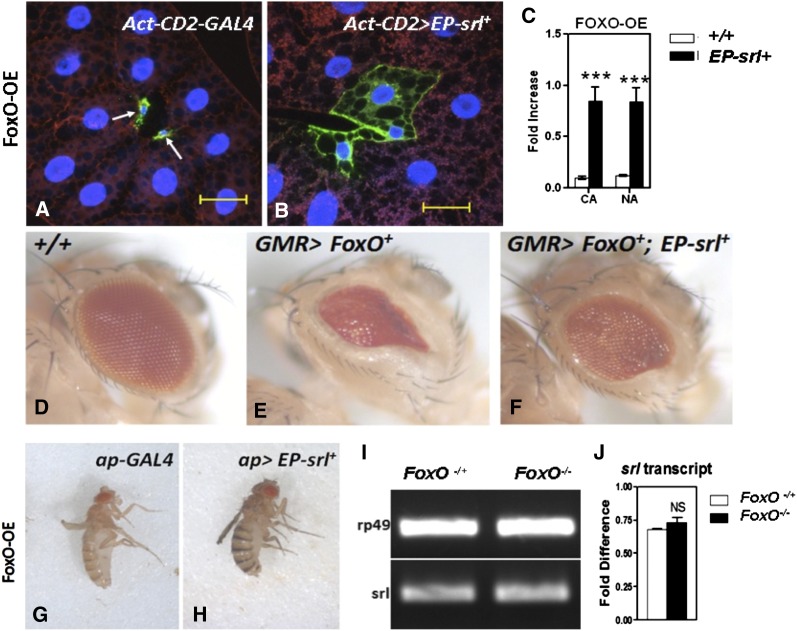

Excess Spargel subdues FoxO overexpression defect:

Fork head box-O (FoxO) transcription factor is a negative effector in the insulin–signaling pathway (Junger et al. 2003; Puig et al. 2003). When nutrients are in short supply, FoxO slows down insulin signaling by activating 4EBP (4E binding protein), which acts as a global suppressor of translation (Puig et al. 2003; DePalma et al. 2012; Laplante and Sabatini 2012). This action of FoxO minimizes the situation of cellular energy expenditure under stress. Although FoxO has been claimed to be a negative regulator of Spargel transcription activity in Drosophila S2 cells (Gershman et al. 2007), we noticed no changes in Spargel transcription activity in the FoxO-null situation (Figure 5, I and J). To obtain further insight on FoxO–Spargel interaction, we co-overexpressed them in the same cell. FoxO overexpression in larval fat body causes the cells to be unhealthy with very tiny nuclei and little to no cytoplasmic area, when compared to the neighboring control cells outside the clone (Figure 5A). When Spargel is produced in excess, we found ∼11% of FoxO-OE cell clones attain their normal size (Figure 5, A–C). Similarly, excess Spargel is capable of slightly improving the FoxO-mediated phenotypic severities in the wing and the eye tissue (Figure 5, D–H). While excess Spargel ameliorates the severity of FoxO overexpression in a tissue-limited fashion, the lethal effect of ubiquitous FoxO overexpression cannot be rescued with Spargel (Table S2). As a transcription factor, FoxO regulates multiple targets, which in turn influences various cellular processes in vital tissues (Accili and Arden 2004; Greer and Brunet 2005). Our experiments show that levels of Spargel overexpression that were able to rescue the TOR and S6K effects in the fat body are not capable of producing a similar high percentage of rescue of the FoxO overexpression phenotype. Therefore we suggest that Spargel does not share all of the FoxO functions and consequently cannot significantly rescue the FoxO phenotypes, or it is possible that Spargel function is not enough to take over any of these functions, hence only a limited rescue happened.

Figure 5.

Spargel and FoxO interaction. (A) Overexpression of FoxO severely affects cell growth (arrows). It is possible that the FoxO OE cells will die before even reaching the adult stage. (B) Following Spargel OE, some of these tiny cells (∼11%) attained increased cellular and nuclear areas as quantitated in C. (D) Normal eye. (E) FoxO OE in the eye with GMR-GAL4 driver shows a significant reduction in ommatidial numbers. (F) FoxO OE effect on ommatidial numbers can be ameliorated by Spargel OE (N > 50). (G) Severe wing phenotype resulted when FoxO is overexpressed with apterous-GAL4 driver. (H) Excess Spargel partially fixes the wing defect in H. (I and J) RT–PCR analysis of spargel mRNA expression in FoxO null background revealed that Spargel is not regulated by FoxO. Bar for cell clones, 25 μm; bar for eye, 100 px. CA, cytoplasmic area normalized with control; NA, nuclear area normalized with control. ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant.

Spargel is involved in growth signaling through mitochondrial biogenesis:

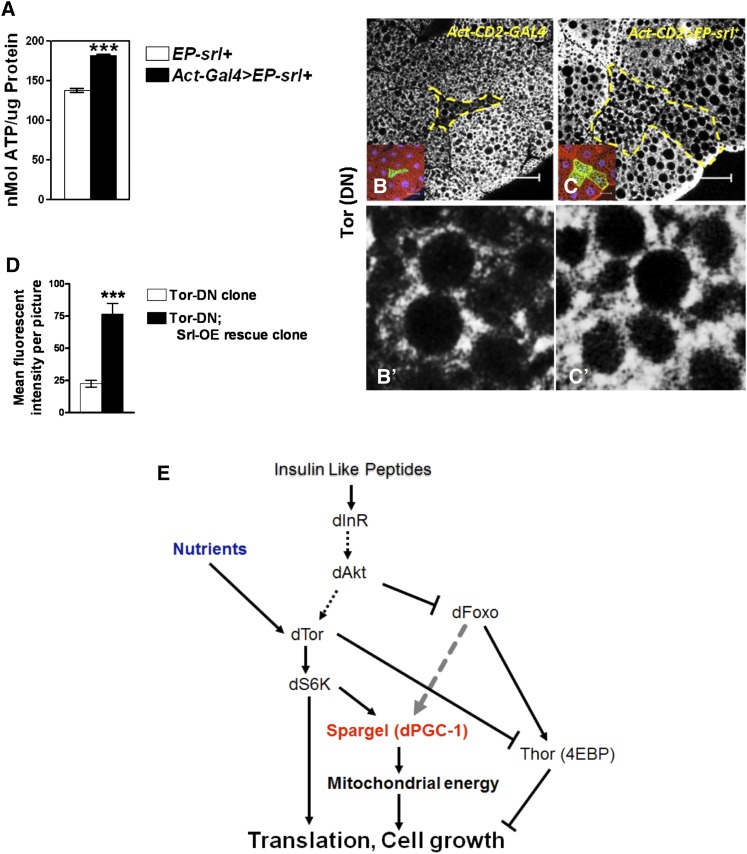

Based on the above observations, we propose an extension of the insulin–TOR signaling pathway in which Spargel is incorporated as a new terminal effector in the cell growth signaling pathway (Figure 6E). Although reduced expressions of many insulin–TOR signaling partners negatively influence cell growth and Spargel does the same, Spargel gain of function is not lethal, nor does it cause any cellular or organismal overgrowth (Figure S1, A–C) (Rera et al. 2011). We now have reasons to believe that Spargel controls the energy flow in this system as mitochondrial energy production is upheld during Spargel overexpression with increased ATP generation (Figure 6A). This observation follows some earlier claims where Spargel overexpression was related to higher activity of electron transport complexes (Rera et al. 2011). Conversely, reduced Spargel level negatively impacted the electron transport chain enzymes and ATP synthesis (Tiefenbock et al. 2010). How is this excess ATP utilized during Spargel overexpression? One clue came from the muscle-specific overexpression of Spargel, which prolongs the vertical climbing behavior in flies (Tinkerhess et al. 2012), possibly due to excess ATP production.

Figure 6.

Modified insulin–TOR pathway including Spargel. (A) Increased ATP production resulted from ubiquitous overexpression of Spargel, (***P < 0.001, NS, not significant). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis with mitochondria-specific ATP-5A antibody revealed that the small-sized TOR(DN) cell clones (yellow border) carry fewer mitochondria (white speckles). Inset shows that TOR(DN) cells were identified as GFP-positive cells. Large fat droplets appeared as black holes are free of mitochondria. (C) Following Spargel OE, TOR(DN) cell clones (three GFP-positive cells in the inset marked with yellow border) attain normal size and their mitochondrial numbers appear to have increased significantly. (B′ and C′) Enlarged view of the portions of the cell clones showing much fewer mitochondria in TOR(DN) cells; however Spargel OE in these cells has vastly improved the mitochondrial numbers in C′. (D) Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity confirmed three times more mitochondria are present in the TOR(DN) cells rescued with Spargel (N > 25). ***P < 0.001. (E) Based on our results we propose a modified insulin–TOR pathway including Spargel as a terminal effector downstream of Tsc-2, TOR, S6K, and FoxO. Since Spargel is a terminal effector, we anticipate that all participants of the insulin-signaling pathway impose their effect on cell size and cell growth through Spargel because Spargel regulates mitochondrial energy metabolism.

When cells need to grow, TOR is activated through phosphorylation either by activated insulin signals or by amino acids. An activated TOR maintains nutrient and energy balance by promoting transcription, protein synthesis, and mitochondrial function (Schieke et al. 2006). So, to consider the possibility that Spargel action is tied to energy supply, we checked the mitochondrial content during Spargel overexpression. Indeed, in TOR(DN) cell clones, the number of mitochondria were far fewer (Figure 6, B, B′, and D) compared to the TOR(DN) cell clones overexpressing Spargel (Figure 6, C, C′, and D). This observation supports our model that Spargel regulates mitochondrial energetics in the growth-signaling pathway (Figure 6E). Being a transcriptional coactivator, Spargel controls an array of genes involved in mitochondrial function, glucose, fat, and protein metabolism (Tiefenbock et al. 2010). In addition to their function in protein production and energy generation, possible involvement of these other factors in cell growth process cannot be ruled out. Finally, based on colocalization of Spargel with splicing complexes suggest that Spargel/dPGC-1 may be involved with processing of a number of cellular mRNAs (Monsalve et al. 2000). Some of those mRNA’s might be important for cell growth as well, although mitochondrial energetics is possibly the centerpiece in this process. Thus, Spargel serves as a final checkpoint in the insulin–TOR pathway for regulation of cell size and cell growth; however, the mechanism of Spargel action remains to be elucidated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Frei, Morris Birnbaum, Linda Partridge, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for providing fly stocks. Acknowledgments are also due to the Howard Hughes Medical Research Scholars Core Facility in the Department of Biology, Howard University. This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant NS039407-06.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: T. Schüpbach

Literature Cited

- Accili D., Arden K. C., 2004. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell 117: 421–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo H., Stewart M. J., 2002. Altering Drosophila S6 kinase activity is consistent with a role for S6 kinase in growth. Genesis 34: 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla K., Hwang B. J., Dewi R. E., Ou L., Twaddel W., et al. , 2011. PGC1alpha promotes tumor growth by inducing gene expression programs supporting lipogenesis. Cancer Res. 71: 6888–6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin M., Raghava G. P., 2004. ESLpred: SVM-based method for subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins using dipeptide composition and PSI-BLAST. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: W414–W419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier E., 2005. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6: 9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brameier M., Krings A., Maccallum R. M., 2007. NucPred–predicting nuclear localization of proteins. Bioinformatics 23: 1159–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. T., Spradling A. C., 2009. Clueless, a conserved Drosophila gene required for mitochondrial subcellular localization, interacts genetically with parkin. Dis. Model. Mech. 2: 490–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham J. T., Rodgers J. T., Arlow D. H., Vazquez F., Mootha V. K., et al. , 2007. mTOR controls mitochondrial oxidative function through a YY1-PGC-1alpha transcriptional complex. Nature 450: 736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePalma M. J., Ketchum J. M., Saullo T. R., Laplante B. L., 2012. Is the history of a surgical discectomy related to the source of chronic low back pain? Pain Physician 15: E53–E58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X. D., Maniatis T., 1992. The 35-kDa mammalian splicing factor SC35 mediates specific interactions between U1 and U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles at the 3′ splice site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89: 1725–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannage-Yared M. H., Klammt J., Chouery E., Corbani S., Megarbane H., et al. , 2012. Homozygous mutation of the Insulin-like Growth Factor-I Receptor gene (IGF1R) in a patient with severe pre- and postnatal growth failure, and congenital malformations. Eur. J. Endocrinol 168: K1–K7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershman B., Puig O., Hang L., Peitzsch R. M., Tatar M., et al. , 2007. High-resolution dynamics of the transcriptional response to nutrition in Drosophila: a key role for dFOXO. Physiol. Genomics 29: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer E. L., Brunet A., 2005. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene 24: 7410–7425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S. S., 2009. Insulin/TOR signaling in growth and homeostasis: a view from the fly world. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41: 1006–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig K. M., Neufeld T. P., 2002. Inhibition of cellular growth and proliferation by dTOR overexpression in Drosophila. Genesis 34: 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig K. M., Colombani J., Neufeld T. P., 2006. TOR coordinates bulk and targeted endocytosis in the Drosophila melanogaster fat body to regulate cell growth. J. Cell Biol. 173: 963–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hietakangas V., Cohen S. M., 2009. Regulation of tissue growth through nutrient sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43: 389–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger M. A., Rintelen F., Stocker H., Wasserman J. D., Vegh M., et al. , 2003. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosugi S., Hasebe M., Matsumura N., Takashima H., Miyamoto-Sato E., et al. , 2009. Six classes of nuclear localization signals specific to different binding grooves of importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M., Sabatini D. M., 2012. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149: 274–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Handschin C., Spiegelman B. M., 2005. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 1: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig Y., Ruas J. L., Estall J. L., Lo J. C., Devarakonda S., et al. , 2011. Separation of the gluconeogenic and mitochondrial functions of PGC-1{alpha} through S6 kinase. Genes Dev. 25: 1232–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron M., Lasko P., Sonenberg N., 2003. Signaling from Akt to FRAP/TOR targets both 4E-BP and S6K in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 9117–9126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsalve M., Wu Z., Adelmant G., Puigserver P., Fan M., et al. , 2000. Direct coupling of transcription and mRNA processing through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Mol. Cell 6: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montagne J., Stewart M. J., Stocker H., Hafen E., Kozma S. C., et al. , 1999. Drosophila S6 kinase: a regulator of cell size. Science 285: 2126–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Ichisaka T., Maeda M., Oshiro N., Hara K., et al. , 2004. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 6710–6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter C. J., Huang H., Xu T., 2001. Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell 105: 357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig O., Marr M. T., Ruhf M. L., Tjian R., 2003. Control of cell number by Drosophila FOXO: downstream and feedback regulation of the insulin receptor pathway. Genes Dev. 17: 2006–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rera M., Bahadorani S., Cho J., Koehler C. L., Ulgherait M., et al. , 2011. Modulation of longevity and tissue homeostasis by the Drosophila PGC-1 homolog. Cell Metab. 14: 623–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B., Liu J., 2003. The PredictProtein server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 3300–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvinsky I., Meyuhas O., 2006. Ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation: from protein synthesis to cell size. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31: 342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel A. R., Kahn C. R., 2001. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature 414: 799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieke S. M., Phillips D., Mccoy J. P., Jr, Aponte A. M., Shen R. F., et al. , 2006. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway regulates mitochondrial oxygen consumption and oxidative capacity. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 27643–27652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak M. A., Storey B. T., Peterside I., Simmons R. A., 2003. Impaired oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of intrauterine growth-retarded rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 285: E130–E137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiefenbock S. K., Baltzer C., Egli N. A., Frei C., 2010. The Drosophila PGC-1 homologue Spargel coordinates mitochondrial activity to insulin signalling. EMBO J. 29: 171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinkerhess M. J., Healy L., Morgan M., Sujkowski A., Matthys E., et al. , 2012. The Drosophila PGC-1alpha homolog spargel modulates the physiological effects of endurance exercise. PLoS ONE 7: e31633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N., 2006. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124: 471–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Stallock J. P., Ng J. C., Reinhard C., Neufeld T. P., 2000. Regulation of cellular growth by the Drosophila target of rapamycin dTOR. Genes Dev. 14: 2712–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Billington C. J., Jr, Pan D., Neufeld T. P., 2006. Drosophila target of rapamycin kinase functions as a multimer. Genetics 172: 355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.