Abstract

Objectives

We sought to identify factors associated with harmful microinjecting practices in a longitudinal cohort of IDU.

Methods

Using data from the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) between January 2004 and December 2005, generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression was performed to examine sociodemographic and behavioral factors associated with four harmful microinjecting practices (frequent rushed injecting, frequent syringe borrowing, frequently injecting with a used water capsule, frequently injecting alone).

Results

In total, 620 participants were included in the present analysis. Our study included 251 (40.5%) women and 203 (32.7%) self-identified Aboriginal participants. The median age was 31.9 (interquartile range: 23.4–39.3). GEE analyses found that each harmful microinjecting practice was associated with a unique profile of sociodemographic and behavioral factors.

Discussion

We observed high rates of harmful microinjecting practices among IDU. The present study describes the epidemiology of harmful microinjecting practices and points to the need for strategies that target higher risk individuals including the use of peer-driven programs and drug-specific approaches in an effort to promote safer injecting practices.

Keywords: injection drug use, harmful, Vancouver, microinjecting practices

BACKGROUND

In addition to high rates of morbidity from cutaneous injection-related infections including abscesses and cellulitis (Dwyer et al., 2009; Lloyd-Smith 2008; Lloyd-Smith et al., 2005; Palepu et al., 2001), individuals who inject drugs (IDU) have been recognized as a group at high-risk for the acquisition of blood-borne viruses including Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) (Aceijas, Stimson, Hickman, and Rhodes, 2004; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009; Spradling et al., 2010). Importantly, transmission occurs largely through the sharing of contaminated-injecting paraphernalia (Freeman, Williams, and Sanders, 1999; Hamers et al., 1997; Strathdee et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2001). In response, a range of interventions has been developed with the primary focus on the reduction of syringe sharing, such as needle exchange programs (NEPs) (Des Jarlais, Arasteh, Semaan, and Wood, 2009; Des Jarlais et al., 2000; Hurley and Jolley, 1997).

However, it is well known that injection is a complex process that requires knowledge and technical proficiency. Injecting involves many steps and significant harm can result at any point in this process (Des Jarlais et al., 2009; Hagan and Des Jarlais, 2000). Therefore, we sought to examine a range of harmful microinjecting practices as a means of informing a comprehensive public health response.

METHODS

Study Setting

Vancouver's Downtown Eastside (DTES), a highly impoverished neighborhood, comprises of a 10-city block radius and is an epicenter of unstable housing, open and intense drug use, and explosive outbreaks of infectious disease (e.g., HIV and HCV). There are an estimated 5,000 people who inject drugs in the DTES (Strathdee et al., 1997a). Pronounced poverty, measured in mean income, contributes to the DTES being classified as Canada's poorest postal code (Buxton, 2007). As a result of exposure to the open drug scene in the DTES and associated drug use, elevated levels of risk behaviors (e.g., sharing of syringes) have been observed (Corneil et al., 2006; Milloy et al., 2008; Small, Kerr, Charette, Schechter, and Spitall, 2006; Wood and Kerr, 2006). Further, IDU in this setting frequently contend with unstable housing environments, infectious diseases, and structural forces (e.g., policing, incarceration, urban development) that mediate the health of some of the more marginalized individuals living in this community. At the same time several health services have been initiated, including NEPs, a contact center, a street nurse program and most recently a supervised injection facility (Kerr et al., 2006).

Study Sample

The first investigation into injection drug use in the DTES was the Point Project, a case-control study of 288 IDU set up in 1995 to examine risk factors for HIV infection (Patrick et al., 1997; Strathdee et al., 1997b). This study was the precursor for the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) which is an open prospective study that has enrolled and followed 1,603 IDU recruited through self-referral or street outreach from Vancouver's DTES, since May 1996. Research from VIDUS has examined a variety of aspects of drug use from individual and environmental levels. In terms of infectious disease outcomes, VIDUS has identified that nearly 30% of cohort participants are HIV positive and 90% are HCV positive (Patrick et al., 2001; Tyndall et al., 2003). Additionally, persons of Aboriginal decent, over-represented in the DTES community, are more than two times more likely to be HIV-positive (Wood et al., 2008). Research from VIDUS has highlighted the devastating effects and extensiveness of drug use and infectious disease transmission in Vancouver's DTES.

The cohort has been described previously in detail (Tyndall et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2001). In brief, individuals were eligible for participation if they were 14 years of age or older, had injected illicit drugs at least once in the month prior to enrolment, resided in the Greater Vancouver area, and provided written informed consent. At baseline and semi-annually, participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire which elicits demographic data including age, sex, and place of residence, and information regarding injection and non-injection drug use, injection practices, sexual risk behaviors, and enrolment into addiction treatment. Participants also provide venous blood samples, which are tested for HIV and HCV antibodies. All subjects receive at $20 stipend to compensate for their time and cover transportation costs to the study office located in the heart of the DTES community. This study has been approved by the University of British Columbia's Research Ethics Board.

Statistical Analysis

Our analysis examined correlates between harmful microinjecting practices and sociodemographic characteristics, drug use, and other high-risk behaviors over time. We use the term “microinjecting” in the present study to refer to a detailed examination of the injection process at the individual level. More specifically, we use the term here to represent risks associated with individual self-injection rather than the risks associated with the injection of small amounts of drugs. All participants who were currently injecting and had at least one follow-up visit between January 2004 and December 2005 were eligible for inclusion in the present analysis. To begin, we explored time-invariant background characteristics. We examined four separate harmful microinjecting practices as our dependent variables of interest: frequent rushed injecting, frequent syringe borrowing, frequently injecting with a used water capsule, and frequently injecting alone. While injecting alone may be protective in that an individual injecting outside of risky injecting networks may be at reduced risk of infectious disease transmission, here we consider the associated harmful effects including risk of fatal or nonfatal overdose. For example, no one would be available to contact emergency services in the event of an adverse reaction related to injecting. Responses were coded “frequent” if a participant had reported engaging in each practice examined 75% of the time or more. Independent variables of interest included: age (per year older), sex (female vs. male), Aboriginal ethnicity (yes/no), Downtown Eastside (DTES) residence (yes/no), homelessness (yes/no), HIV status (yes/no), years injecting (per year), daily heroin injection (yes/no), daily cocaine injection (yes/no), syringe borrowing (yes/no), requiring help injecting (yes/no), public injecting (yes/no), incarceration (yes/no), involvement in the sex trade (yes/no), and whether police presence had affected where IDU buy or use drugs or access clean needles (yes/no). Behavioral variables refer to the six-month period prior to the interview.

We examined each harmful microinjecting practice and covariates associated during the follow-up using generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression. This approach is longitudinal in nature and accommodates changes in predictor variables over time. Variables potentially associated with each harmful microinjecting practice were examined in bivariate GEE analyses. We fit four individual multivariate logistic GEE models using an a priori-defined model building protocol that involved adjusting for age, gender, Aboriginal ethnicity, and all other explanatory variables statistically significant at the p < .05 in bivariate analyses. In the present study, members of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), a well-recognized drug user organization, assisted in the interpretation of study findings. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 8.0 (SAS, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

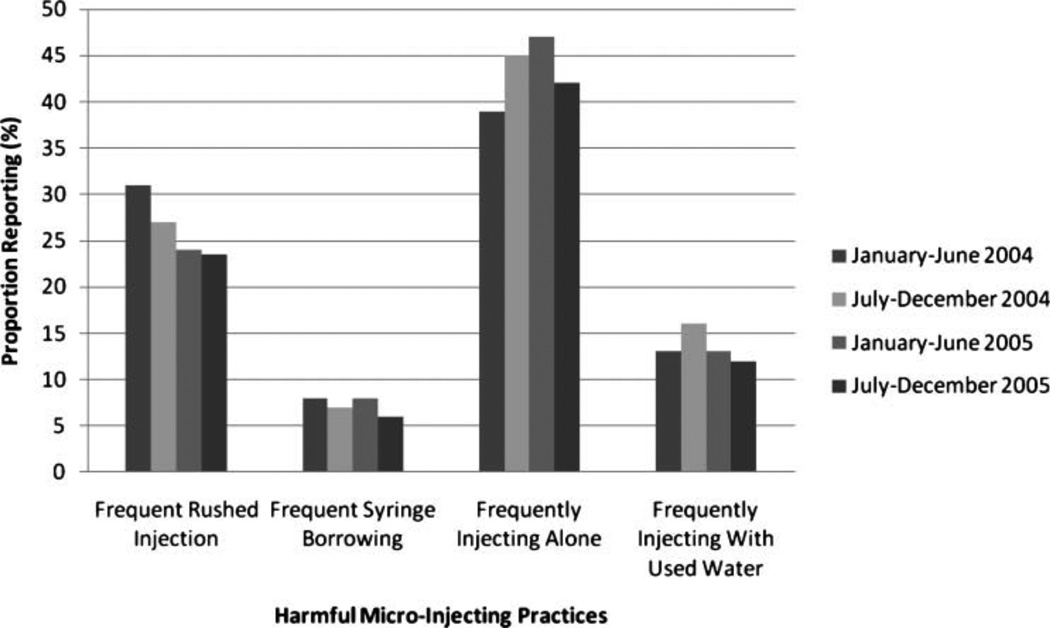

In total, 620 participants were currently injecting, had a least one follow-up visit between January 2004 and December 2005 and were included in the present analysis. Sociodemographic characteristics of included participants reported at baseline are presented in Table 1. The proportion of participants who reported engaging in each harmful microinjecting practice on a frequent basis is presented in Figure 1 (each bar represents a different time period corresponding to a different follow-up visit). The proportion reporting frequent rushed injection ranged from 23% to 31%; 7% to 9% reported frequent syringe borrowing; 39% to 47% reported frequently injecting alone; and 12% to 15% reported frequently using a used water capsule for injection.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of included participants at baseline (n = 620).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (IQR)* | 31.9 (25.4–39.3) |

| Years Injecting | |

| Median (IQR)* | 16.8 (10.2–27.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 369 (59.5) |

| Female | 251 (40.5) |

| Aboriginal ethnicity | |

| No | 414 (67.3) |

| Yes | 203 (32.7) |

| Downtown Eastside (DTES) residence** | |

| No | 233 (37.6) |

| Yes | 387 (64.2) |

| HIV-positive | |

| No | 401 (68.8) |

| Yes | 182 (31.2) |

| Homeless** | |

| No | 541 (87.3) |

| Yes | 79 (12.7) |

| Sex trade involvement** | |

| No | 496 (80.0) |

| Yes | 124 (20.0) |

IQR: Interquartile Range.

Activities referring to previous six months.

Figure 1.

Proportion reporting four harmful microinjecting practices between January 2004 and December 2005 (n=620).

Note: Each bar corresponds to a different follow-up visit between January 2004 and December 2005.

Longitudinal analyses are presented in Table 2 and three with bivariate results displayed in Table 2 and multivariate results displayed in Table 3. Reporting frequent rushed injection was associated with public injecting [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 4.06, 95% confidence intervals (CI): 2.81–5.88], daily heroin injection (AOR = 2.12, 95% CI: 1.62–2.78), being affected by police presence (AOR = 1.90, 95% CI: 1.36–2.67), sex trade involvement (AOR = 1.68, 95% CI: 1.17–2.42), requiring help injecting (AOR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.17–2.23), incarceration (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.01– 2.08), daily cocaine injection (AOR = 1.42, 95% CI: 1.08–1.87), and younger age (AOR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.06).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and behavioral factors associated with four harmful microinjecting practices in bivariate GEE analyses.

| Frequent rushed injection |

Frequent syringe borrowing |

Frequently injecting alone |

Frequently injecting with used water |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year older) | 1.07 (2.05–1.09)** | 1.03 (1.01–1.06)* | 1.00 (0.98–1.01) | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) |

| Years injecting (per year) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96)** | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) |

| Female gender (yes vs. no) | 1.45 (1.09–1.94)* | 0.82 (0.52–1.29) | 0.68 (0.53–0.87)* | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) |

| Aboriginal ethnicity (yes vs. no) | 1.40 (1.04–1.89)* | 0.53 (0.32–0.89)* | 0.81 (0.63–1.04) | 0.56 (0.43–0.72)** |

| Downtown Eastside (DTES) residence (yes vs. no) | 1.18 (0.91–1.53) | 0.42 (0.28–0.64)** | 1.07 (0.84–1.36) | 1.08 (0.85–1.37) |

| HIV-positive (yes vs. no) | 0.99 (0.73–1.36) | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | 0.97 (0.75–1.26) | 1.30 (1.00–1.68)* |

| Homeless (yes vs. no) | 2.81 (2.05–3.86)** | 1.26 (0.76–2.09) | 0.81 (0.61–1.08) | 1.21 (0.90–1.62) |

| Daily heroin use (yes vs. no) | 2.86 (2.22–3.70)** | 1.60 (1.08–2.36)* | 0.89 (0.71–1.11) | 1.53 (1.21–1.93)** |

| Daily cocaine use (yes vs. no) | 1.64 (1.30–2.06)** | 1.60 (1.09–2.34)* | 0.85 (0.68–1.06) | 1.28 (1.01–1.62)* |

| Public injecting (yes vs. no) | 5.75 (4.18–7.91)** | 1.53 (0.93–2.53) | 0.89 (0.66–1.21) | 0.82 (0.59–1.13) |

| Help injecting (yes vs. no) | 1.94 (1.46–2.57)** | 1.34 (0.87–2.07) | 0.76 (0.60–0.97)* | 2.28 (1.76–2.96)** |

| Sex trade (yes vs. no) | 2.17 (1.60–2.93)** | 1.06 (0.63–1.79) | 1.08 (0.83–1.41) | 1.21 (0.91–1.63) |

| Incarceration (yes vs. no) | 2.06 (1.49–2.85)** | 1.90 (1.19–3.05)* | 0.75 (0.56–1.00)* | 1.35 (1.00–1.83)* |

| Police presence (yes vs. no) | 3.66 (2.83–4.74)** | 1.09 (0.72–1.66) | 0.89 (0.70–1.15) | 1.62 (1.25–2.10)** |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

All variables refer to the last six months. Daily heroin and daily cocaine use refers to injecting at least once daily. Police presence refers to whether police presence had affected where IDU buy or use drugs or access clean needles.

Table 3.

Sociodemographic and behavioral factors associated with four harmful microinjecting practices in multivariate GEE analyses.

| Frequent rushed injection |

Frequent syringe borrowing |

Frequently injecting alone |

Frequently injecting with used water |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year older) | 1.04 (1.01–1.06) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) |

| Years injecting (per year) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | — | — | — |

| Female gender (yes vs. no) | 0.88 (0.62–1.26) | 0.86 (0.52–1.42) | 0.68 (0.53–0.88)* | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) |

| Aboriginal ethnicity (yes vs. no) | 1.24 (0.90–1.69) | 0.58 (0.34–0.98)* | 0.86 (0.66–1.12) | 0.56 (0.42–0.74)** |

| Downtown Eastside (DTES) residence (yes vs. no) | — | 0.40 (0.26–0.61)** | — | — |

| HIV-positive (yes vs. no) | — | — | — | 1.49 (1.15–1.94)* |

| Homeless (yes vs. no) | 1.45 (0.99–2.11) | — | — | — |

| Daily heroin use (yes vs. no) | 2.12 (1.62–2.78)** | 1.41 (0.94–2.11) | — | 1.40 (1.10–1.79)** |

| Daily cocaine use (yes vs. no) | 1.42 (1.08–1.87)* | 1.76 (1.16–2.65)** | — | 1.08 (0.85–1.38) |

| Public injecting (yes vs. no) | 4.06 (2.81–5.88)** | — | — | — |

| Help injecting (yes vs. no) | 1.62 (1.17–2.23)* | — | 0.79 (0.62–1.00) | 2.19 (1.67–2.86)** |

| Sex trade (yes vs. no) | 1.68 (1.17–2.42)* | — | — | — |

| Incarceration (yes vs. no) | 1.45 (1.01–2.08)* | 1.61 (0.97–2.67) | 0.71 (0.53–0.96)* | 1.15 (0.84–1.58) |

| Police presence (yes vs. no) | 1.90 (1.36–2.67)** | — | — | 1.26 (0.99–1.60) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

All variables refer to the last six months. Daily heroin and daily cocaine use refers to injecting at least once daily. Police presence refers to whether police presence had affected where IDU buy or use drugs or access clean needles.

Frequent syringe borrowing was positively associated with daily cocaine injection (AOR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.16–2.65). Living in the DTES (AOR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.26–0.61) and Aboriginal ethnicity (AOR = 0.58, 95% CI: 0.34–0.98) were both negatively associated with frequent syringe borrowing.

Frequently reporting injecting with a used water capsule was positively associated with requiring help injecting (AOR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.67–2.86), being HIV-positive (AOR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.15–1.94), and daily heroin injection (AOR = 1.40, 95% CI: 1.10–1.79), but was negatively associated with Aboriginal ethnicity (AOR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.42–0.74).

Frequently injecting alone was negatively associated with being female (AOR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.53–0.88) and incarceration (AOR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.53–0.96).

DISCUSSION

The present study suggests that harmful microinjecting practices are common among local IDU and are associated with different sociodemographic and behavioral factors. Among the harmful injecting practices considered, reporting frequent rushed injecting and frequently injecting alone were most prevalent among local IDU.

Individuals in this study who reported living in the DTES were less likely to report frequent syringe borrowing. Notably, the NEP operating in Vancouver's DTES is one of the largest in North America (Strathdee et al., 1997a) and our findings suggest that although some levels of syringe borrowing persist in our setting, syringes are available and accessible in the DTES. However, recent evidence suggests that harm reduction supplies are not equally available in throughout the province of British Columbia (Buxton et al., 2008; Spittal et al., 2007) although best practice guidelines indicate that the distribution of needles and syringes should be comparable to the distribution of other necessary injecting supplies, including sterile water (Buxton et al., 2008). Therefore, our findings highlight the need for the widespread distribution and availability of all injecting supplies necessary for a safe and hygienic injection, both within and outside the DTES. Further examination into geographic variability of harm-reduction service utilization is important to inform where the expansion of services is most needed.

Participants who reported public injecting, recent incarceration, as well as individuals who reported having been affected by police presence were all more likely to report frequent rushed injection. Importantly, environmental influences such as geographic location (Freeman et al., 1999; Haw and Higgins, 1998; Maas, Fairbairn, Kerr, Li, Montaner, and Wood, 2007; Rhodes, 2002; Rhodes, Singer, Bourgois, Friedman, and Strathdee, 2005) and the social context of specific injecting environments (Celentano et al., 1991; Dovey, Fitzgerald, and Choi, 2001; Ouellet, Jimenez, Johnson, and Wiebel, 1991; Rhodes et al., 2006) are known to influence risk-taking among IDU. Public injection drug use, for example, has been associated with high-risk injecting behaviors and risk for cutaneous injection-related infections, injection-related vein damage, and HIV and HCV transmission (Rhodes et al., 2006; Small, Rhodes, Wood, and Kerr, 2007). Given the high rates of drug use and other illicit activity (Buxton, 2003), the DTES community has been heavily policed, and police crackdowns, common to the area, have been shown to unintentionally foster high-risk injection practices among IDU (Eby, 2006; Small et al., 2006). These crackdowns also have the unintended effect of driving drug users away from the area further displacing them from health and harm reduction services (Csete and Cohen, 2003; Wood et al., 2004). A fear of interruption and increased anxiety largely attributable to police presence has previously been linked with rushed injecting and may prompt unsafe disposal of injecting paraphernalia and result in accidental syringe sharing (Miller, Strathdee, Kerr, Li, and Wood, 2006a; Small et al., 2007). Regardless, the police have a particular responsibility to ensure that their presence and actions do not produce harm and others have recommended that police officers should not intervene at the point of injection (Maher and Dixon, 1995). However, the impact of drug enforcement on drug users’ ability to protect themselves from HIV/AIDS often goes unnoticed.

Interestingly, both daily heroin and daily cocaine injection were associated with reporting frequent rushed injection. However, it may be that different drugs are injected in a hurried fashion for different reasons. For example, previous research has suggested that rushing associated with daily heroin use may be a result of feeling anxious due to “dope sickness” (Shannon et al., 2007) and the desire to alleviate withdrawal symptoms. In the case of cocaine injection, rushed injection may be partially attributed to cocaine's short half-life reflecting the desire to inject often in order to continuously feel the effects of the drug (Magura, Kang, Nwakeze, and Demsky, 1998). Rushing may be related to this need to inject frequently but may also relate to compulsive behavior associated with the effects of the drug itself and some research has suggested that the effects of cocaine is greatest when it is administered rapidly (Abreu, Bigelow, Fleisher, and Walsh, 2001). It is worth noting that in our setting, both daily cocaine and daily heroin have been associated with patterns of binge drug use where an individual engages in high-intensity compulsive drug runs injecting more frequently than normal (Miller et al., 2006b). Nevertheless, the current findings support the need for evidence-based drug-specific interventions, given that the risk profile varies among consumers of different types of drugs. Incorporated, could be the expansion of peer-driven intervention models that have been shown to be effective in reaching high-risk injectors while addressing critical gaps in service delivery (Broadhead et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2003). Such models could also include those that are culturally appropriate and relevant to Aboriginal communities.

Importantly, drug user-led organizations have been emerging globally and have demonstrated that drug users can organize themselves and make valuable contributions to their communities (Kerr et al., 2006). In our setting, the VANDU Injection Support Team engages in outreach and provides referrals to local IDU. As the team is composed of members of the drug-user community within the DTES, they are well positioned to recognize and understand the complex and varied patterns of use among local IDU. This knowledge and understanding of real drug use-related experiences faced by users can further be used in the design of specific interventions and there remains an ethical imperative to involve IDU populations in research (Kleinig and Einstein, 2006). In our setting, there has been much discussion on the need for effective and appropriate policies that encourage the provision of information and materials (Fast, Small, Wood, and Kerr, 2008; Wood et al., 2008) that serve to reduce harm, including those that can be incorporated into existing harm reduction programs such as the local supervised injecting facility. In addition to mobilizing local IDU as vital social agents of change, there remains an equally important need for adequate knowledge translation activities that serve to inform both policy makers as well as the broader community on the nature and effects of local evidence-based harm reduction programs currently in operation. VANDU performs a critical education function by exposing outsiders to the realities of daily life for drug users in Vancouver's DTES (Kerr et al., 2006). Findings from the present study have the potential to benefit both participants, as well as nonparticipants, in the community if the reported findings inform or are incorporated into public policy.

There are limitations of this study. First, VIDUS is not a random sample and therefore, findings from this analysis may not generalize to the wider population of IDU. Importantly, elevated levels of HIV and related risk behavior among IDU in our setting and others, may be influenced by poor living conditions (Rhodes et al., 2005; Song, Safaeian, Strathdee, Vlahov, and Celentano, 2000) and evidence points to disproportionate levels of drug use and injection among the urban poor (Galea, Nandi, and Vlahov, 2004). A lack of socioeconomic resources (Song et al., 2000) and the treatment of drug users as “criminals” continues to exacerbate social marginalization (***Csete, 2007) and stigmatizing practices against IDU—whether at the level of the individuals, community, institutions, or policies—often impede the development and delivery of effective public health interventions (Friedman and Reid, 2002; Kerr et al., 2006; Rhodes et al., 2005). However it is important to recognize that people who inject drugs are not, in themselves, a homogenous population and although we focused predominately on individual-level behaviors in the present study, we recognize that such behaviors are shaped by an individual's social, political, economic, and physical environments (Rhodes et al., 2005). While recent analyses indicate that the VIDUS cohort is representative of IDU in the DTES community (Tyndall et al., 2001), findings from the present study should be generalized and interpreted with caution. Second, because our study relied on self-report data regarding drug use and injecting practices, our analysis could be subject to social desirability responding bias. Participants may have under-reported harmful microinjecting practices, which would make our estimates conservative. However, it has been suggested that self-report among IDU is generally valid (Darke, 1998). Third, unmeasured factors predictive of high-risk activity among IDU including anxiety levels related to police presence and social network dynamics may have also contributed to the observed findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In the present study, we found high rates of unsafe injecting practices among IDU in Vancouver. In particular, frequent rushed injecting and frequently injecting alone were highly prevalent. However, we did not find a consistent set of sociodemographic or behavioral factors that predicted the harmful microinjecting practices examined. Instead we found that each harmful microinjecting practice was associated with a unique profile of sociodemographic and behavioral factors, which may reflect, in part, the heterogeneity of IDU both in our setting. While there are a variety of harm reduction programs in place locally, our study suggests that harmful injecting practices persist in the community and novel responses to these problems are needed. In addition to evidence-based drug-specific interventions that are culturally appropriate, other approaches should consider involving drug user-led outreach efforts and the increased participation of IDU in research and decision-making processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would particularly like to thank the VIDUS participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past VIDUS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance. In addition, we would like to thank the members of the VANDU Injecting Support Team for their input in interpretation of the study findings. The study was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01 DA011591) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (HHP-67262), including a CIHR community-based research grant (CBR-79873). Thomas Kerr is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- Abreu ME, Bigelow GE, Fleisher L, Walsh SL. Effect of intravenous injection speed on responses to cocaine and hydromorphone in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:76–84. doi: 10.1007/s002130000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aceijas C, Stimson GV, Hickman M, Rhodes T. Global overview of injecting drug use and HIV infection among injecting drug users. AIDS. 2004;18:2295–2303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, Anthony DL, Madray H, Mills RJ, et al. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Reports. 1998;113:42–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton J. Vancouver drug Use Epidemiology. [Accessed November 10, 2005];Site Report for the Canadian Community Epidemiology of drug Use. 2003 from www.vancouver.ca/Foupillaro/pdf/reportvancouver2003.pdf.

- Buxton J. Vancouver drug use epidemiology. Vancouver, Canada: Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buxton JA, Preston EC, Mak S, Harvard S, Barely J BC Harm Reduction supply distribution in British Columbia. More than just needles: an evidence-informed approach to enhancing harm reduction supply distribution in British Columbia. Harm Reduction Journal. 2008;5:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Cohn S, Anthony JC, Solomon L, Nelson KE. Risk factors for shooting gallery use among intravenous drug users. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;811:1291–1295. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.10.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV infection among injection drug users-34 states, 2004–2007. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2009;58:1291–1295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceste J. Aids and Public Security: The other side of the coin. Lancet. 2007;369:720–721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneil TA, Kuyper LM, Shoveller J, Hogg RS, Li K, Spittal PM, et al. Unstable housing, associated risk behaviour, and increased risk for HIV infection among injection drug users. Health and Place. 2006;12:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csete J, Cohen J. Human rights in Vancouver: Do injection drug users have a friend in city hall? Canadian HIV/AID Policy and Law Review. 2003;8:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. Self-report among injecting drug users: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;51:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Semaan S, Wood E. HIV among injecting drug users: current epidemiology, biologic markers, respondent-driven sampling, and supervised-injection facilities. Current Opinions on HIV/AIDS. 2009;4:308–313. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832bbc6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais D, Marmor M, Friedmann P, Titus S, Aviles E, Deren S, et al. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1992–1997: evidence for a declining epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:352–359. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K, Fitzgerald JL, Choi Y. Safety becomes danger: dilemmas of drug-use in public space. Health and Place. 2001;7:319–331. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(01)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer R, Topp L, Maher L, Power R, Hellard M, Walsh N, et al. Prevalences and correlates of non-viral injecting-related injuries and diseases in a convenience sample of Australian injecting drug users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby D. The political power of police and crackdowns: Vancouver’s example. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Fast D, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. The perspectives of injection drug users regarding safer injecting education delivered through a supervised injecting facility. Harm Reduction Journal. 2008;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-5-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman R, Williams ML, Sanders LA. Drug use, AIDS knowledge and HIV risk behaviours of Cuban-, Mexican-, and Puerto Rican-born drug injectors who are recent entrants into the United States. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999;34:1765–1793. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Reid G. The need for dialectical models as shown in the response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. International Journal of Sociology. 2002;22:177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of drug use. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC. HIV and HCV infection among injecting drug users. Mt. Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2000;67:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamers FF, Batter V, Downo AM, Alix J, Cazein F, Brunet JB. The HIV epidemic associated with injection drug use in Europe: geographic and time trends. AIDS. 1997;11:1365–1374. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haw S, Higgins K. A comparison of the prevalence of HIV infection and injecting risk behaviour in urban and rural samples in Scotland. Addiction. 1998;93:855–863. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9368557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley SF, Jolley DJ. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. Lancet. 1997;349:1797–1801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Peeace W, Douglas D, Pierre A, Wood E. Harm reduction by a ‘user-run’ organization: a case study of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinig J, Einstein S. Ethical challenges for intervening in drug use: policy, research and treatment issues. Huntsville, TX: OICJ; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Risk factors for developing cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2008;9:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith E, Kerr T, Hogg RS, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Prevalence and correlates of abscesses among a cohort of injection drug users. Harm Reduction Journal. 2005;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas B, Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Neighbourhood and HIV infection among IDU: place of residence independently predicts HIV infection among a cohort of injection drug users. Health and Place. 2007;17:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Kang SY, Nwakeze PC, Demsky S. Temporal patterns of heroin and cocaine use among methadone patients. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33:2441–2467. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher L, Dixon D. Policing and public health: law enforcement and harm minimization in a street-level drug market. British Journal of Criminology. 1995;39:488–512. [Google Scholar]

- Miller C, Strathdee SA, Kerr T, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injection drug use: implications for intervention programs. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006a;38:462–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Kerr T, Frankish JC, Spittal PM, Li K, Schechter MT, et al. Binge drug use independently predicts HIV seroconversion among injection drug users: implications for public health strategies. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006b;41:199–210. doi: 10.1080/10826080500391795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milloy MJ, Wood E, Small W, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner J, et al. Incarceration experiences in a cohort of active injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27:693–699. doi: 10.1080/09595230801956157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet L, Jimenez AD, Johnson W, Wiebel W. Shooting galleries and HIV disease variations in places for injecting illicit drugs. Crime and Delinquency. 1991;37:64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Leon H, Muller J, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, et al. Hospital utilization and costs in a cohort of injection drug users. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;165:415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DM, Tyndall MW, Cornelisse PG, Li K, Sherlock CH, Rekart ML, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C virus infection among injection drug users during an outbreak of HIV infection. CMAJ. 2001;165:889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DM, Strathdee SA, Archibald CP, Ofner M, Craib KJ, Cornelisse PG, et al. Determinants of HIV seroconversion in injection drug users during a period of rising prevalence in Vancouver. International Journal of STDs and AIDS. 1997;8:437–445. doi: 10.1258/0956462971920497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. The ‘risk’ environment: a framework for understanding and reducing drug related harm. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2002;13:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Kimber J, Small W, Fitzgerald J, Kerr T, Hickman M, et al. Public injecting and the need for ‘safer environment interventions’ in the reduction of drug-related harm. Addiction. 2006;101:1385–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;66:911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Rhodes T, Wood E, Kerr T. Public injection settings in Vancouver: physical environment, social context and risk. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of an intensified police activity on injection drug users: evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Song JY, Safaeian M, Strathdee SA, Vlahov D, Celentano DD. The prevalence of homelessness among injection drug users with and without HIV infection. Journal of Urban Health. 2000;77:678–687. doi: 10.1007/BF02344031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittal PM, Craib KJ, Teegee M, Baylis C, Christian WM, Moniruzzaman AK, et al. The Cedar project: prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among young Aboriginal people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2007;66:226–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling PR, Richardson JT, Buchacz K, Moorman AC, Finelli L, Bell BP, Brooks JT the HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. Trends in hepatitis C virus infection among patients in the HIV outpatient study, 1996–2007. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53:388–396. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b67527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, van Ameijden EJ, Mesquita F, Wodak A, Rana S, Vlahov D. Can HIV epidemics among injection drug users be prevented? AIDS. 1998;12:s71–s79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PGA, Rekart M, Montaner JSG, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug users study. AIDS. 1997a;11:F59–F65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Archibald CP, Ofner M, Cornelisse PG, Rekart M, et al. Social determinants predict needle-sharing behaviour among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction. 1997b;92:1339–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Currie P, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17:887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Craib KJP, Currie S, Li K, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Impact of HIV infection on mortality in a cohort of injection drug users. Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2001;28:351–357. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200112010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AR, Wood E, Lai C, Tyndall MW, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Nurse-delivered safer injection education among a cohort of injection drug users: evidence from the evaluation of Vancouver’s supervised injection facility. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2008;19:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JS, Li K, Zhang R, Barney L, Strathdee SA, et al. Burden of HIV infection among aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver, British Columbia. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:515–519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Kerr T, Hogg RS, et al. Unsafe injection practices in a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver: could safer injecting rooms help? Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;165:405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T. What do you do when you hit rock bottom? Responding to drugs in the city of Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Spittal PM, Small W, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. An evaluation of a peer-run ‘unsanctioned’ syringe exchange program. Journal of Urban Health. 2003;80:455–464. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Spittal PM, Li K, Ken T, Miller CL, Nogg RS, Montaner JS, Schechter MT. Inability to access addiction treatment and risk of HIV-infection among injection drug users. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36:750–754. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200406010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]