Abstract

Background

Knee OA is a chronic disease associated with significant morbidity and economic cost. The efficacy of acupuncture in addition to traditional physical therapy has received little study.

Objective

To compare the efficacy and safety of integrating a standardized true acupuncture protocol versus non-penetrating acupuncture into exercise-based physical therapy (EPT).

Methods

This was a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial at 3 physical therapy centers in Philadelphia, PA. We studied 214 patients (66% African-American) with at least 6 months of chronic knee pain and X-ray confirmed Kellgren scores of 2 or 3. Patients received 12 sessions of acupuncture directly following EPT over 6–12 weeks. Acupuncture was performed at the same 9 points dictated by the Traditional Chinese “Bi” syndrome approach to knee pain, using either standard needles or Streitberger non-skin puncturing needles. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients with at least a 36% improvement in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score at 12 weeks.

Results

Both treatment groups showed improvement from combined therapy with no difference between true (31.6%) and non-penetrating acupuncture (30.3%) in WOMAC response rate (p=0.5) or report of minor adverse events. A multivariable logistic regression prediction model identified an association between a positive expectation of relief from acupuncture and reported improvement. No differences were noted by race, sex, or age.

Conclusion

Puncturing acupuncture needles did not perform any better than non-puncturing needles integrated with EPT. Whether EPT, acupuncture, or other factors accounted for any improvement noted in both groups could not be determined in this study. Expectation for relief was a predictor of reported benefit.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Osteoarthritis of the knee, Randomized clinical trial, African American, Non-puncturing needle, physical therapy, placebo controlled, obese patients

INTRODUCTION

Acupuncture is a Traditional Chinese Medicine treatment modality that has gained popularity in the United States (U.S.), especially for painful conditions[1]. Its use among U.S. adults increased from 2 million individuals in 2002 to 3.1 million per year in 2007[2, 3]. Recent high quality clinical trials of acupuncture, suggest that acupuncture may offer clinically relevant benefits when compared to standard medical care or wait listed controls for acupuncture[4–8]; however, studies that compare standard to non-standard needling, either without puncturing the skin or in the wrong acupuncture points have demonstrated smaller or negligible effects [4, 6–11]. A possible interpretation is that much of the acupuncture effects as compared to standard medical care are mediated through the entire process of acupuncture care (including patient-provider interaction, and patient engagement) rather than the specific needling location or techniques[12]. Factors that influence this type of non-specific effect include the patient’s expectation of benefit from the therapy[13–15]. Following a review of the literature on acupuncture with physical therapy[16], we examined these issues using a 2-arm multicenter prospective randomized clinical trial (RCT) designed to determine the specific efficacy and safety of acupuncture integrated with standard exercise-based physical therapy (EPT) for knee OA, in a population that included a large African-American community.

METHODS

Participants

We recruited patients for this trial from September 2001 through December 2006 at 3 physical therapy sites in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, specifically the physical therapy departments at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital, and the Philadelphia VA Medical Center. All patients referred for physical therapy treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee were considered for this trial. Most patients were referred by primary care, rheumatologic, and physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at these hospitals and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

A screening interview was conducted at the first exercise-based physical therapy (EPT) evaluation visit. Eligible patients who signed informed consent provided initial demographic data and were scheduled for 12 combined EPT and acupuncture sessions. At the initial treatment visit the patient underwent EPT therapy and was randomized and administered either real needle acupuncture or non-penetrating needle acupuncture. The same treatment was given during this and all subsequent EPT visits targeting 12 combined treatments.

Inclusion criteria required that patients be age 40 years or older to focus on classic knee OA. Patients had to have pain in 1 or both knee joints for more than 6 months and moderate pain >4/10 for more than 5 out of 7 consecutive days in the week before enrollment. Between the enrollment and first treatment visit, the degree of knee OA was radiologically confirmed as Kellgren–Lawrence score 2 or 3[17], in 1 or both knees on a radiograph obtained within the last year or on an X-ray performed as part of the study. Patients were excluded if they had other diseases known to affect the knee including gout, rheumatoid arthritis and significant trauma; neurologic, cardiac or psychiatric disease that would interfere with a standard EPT program; pregnancy; significant coagulopathy or taking anti-coagulants that would interfere with the safe administration of acupuncture; or previous acupuncture treatment within the last 12 months.

Study Interventions

Exercise-based Physical Therapy (EPT)

All participants received treatment once or twice a week for a maximum of 12 total treatments. The standardized exercise-based program was as vigorous as the subjects could tolerate with routine encouragement by the staff, and included range of motion exercises, muscle strengthening, and aerobic conditioning (bike and/or treadmill apparatus). Resistance was increased as appropriate beginning with a 10-minute program of aerobic activity progressing as tolerated to a goal of 20–30 minutes over the course of therapy.

Acupuncture protocol

In keeping with the STRICTA checklist [18], acupuncture sessions with the puncturing (and non-puncturing) needles were administered following every EPT session once or twice a week by fully trained and licensed acupuncturists, without electrical stimulation or co-intervention. The AsianMed[16] penetrating (Gauge 8 × 1.2″) and identical appearing non-penetrating Streitberger needles were used. Nine acupuncture points for each knee were chosen to be consistent with the traditional Chinese Bi syndrome therapy for knee pain and to be consistent with a previously positive acupuncture study[19]. The primary knee points were GB 34, SP 9, ST 36, ST 35 and Xiyan, and the distal points (located near the ankles) selected were UB 60, GB 39, SP 6, and KI 3 for a total of 9 points. The same points were used for each affected leg. If both knees had pain >3/10, both were treated. The insertion depth for standard needles was between 0.2 to 3 cm depending on the location of the point and patient’s body size. The needles were left in place for 20 minutes, with a brief manipulation at the beginning and end of the treatment. The de qi sensation, a local sensation of achy, distension, and tingling[20], was not required and not specifically recorded.

Non-penetrating acupuncture

The Streitberger non-penetrating needle was used in the control group. The needle appears identical to the real needle except that it is blunt and retracts into the handle when it is pressed against the skin, giving the appearance, and sensation of needle insertion[21]. Both real and non-puncturing needles were placed at exactly the same acupuncture points and held in place by being inserted through a single-layer gauze-retaining mechanism held on by a small doughnut-shaped bandage. Acupuncturists were instructed to not to attempt to stimulate with the Streitberger needle and did not ask about the achievement of de qi to minimize the interaction between the acupuncturist and the patient.

The acupuncturists participating in the study included five licensed physicians trained in acupuncture and three non-physician acupuncturists. Physician acupuncturists all had received at least 300 hours of medical acupuncture training. All non-physician acupuncturists were graduates of accredited schools and licensed in the state of Pennsylvania. All practitioners were trained in the study procedures and their technique was personally observed at least once during the study by an experienced acupuncturist (not participating as an acupuncturist in the trial) to promote consistency of their technique.

Randomization

All patients were randomized with a block size of 6, stratified by acupuncturist. The randomization coding was computer generated by an independent statistician, sealed in individual opaque envelopes, and kept in a lock box in a private room only accessible by the acupuncturist at each site. As each eligible patient was enrolled they were assigned a number in numerical order by the research coordinator, and the matching envelope was retrieved by the acupuncturist.

Blinding

The patients, physical therapists, data collectors, and statistician were blinded throughout the study period. Acupuncture was performed in a separate room to limit the observation by other personnel. The acupuncturists were not blinded due to the nature of the intervention but were trained to interact with each patient in a formalized manner to prevent unblinding. To evaluate the effectiveness of the blinding, each participant was asked at their final intervention to guess which group they were assigned (true, non-penetrating, or unsure).

Outcomes

The a priori primary outcome was the change in the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) total score between baseline and 12 weeks. A clinically important patient response was defined as a change of at least 36% in the WOMAC score, as recommended by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials (OMERACT) group[22, 23]. Our major secondary outcomes included the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)[24]; the mean change in the physical and mental component scores of the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36)[25] and the patient global impression of change (PGIC)[26], using better or much better as a cut-off; and the 6-minute walk test (evaluating the distance a patient could walk comfortably on a flat surface in 6 minutes before EPT) using a 50-ft. increase in distance as the cut-off[27]. Standard demographic and clinical data were obtained via self-report. Patients were also asked before the first treatment to rate whether they expected acupuncture to be helpful for their knee OA, or anyone’s knee OA, with response options of “No”, “Maybe”, and “Yes.”

Our primary end point was the change from baseline to after completion of 12 treatments. We evaluated patients in person during week 6 (mid-treatment) and week 12. For the week 26 assessment we mailed the questionnaire with telephone follow-up. Potential adverse events were actively assessed by asking about any changes in their pain, physical function, psychological state, or other health related areas at each of the physical therapy visits throughout the treatment and 12-week primary outcome period. Any reported changes were noted in the categories listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Adverse Events (N=78) and Withdrawals (32) Reported during Trial*

| Adverse Events | True Acupuncture | Non-penetrating Acupuncture |

|---|---|---|

| Agitation | 2 | 0 |

| Bruising | 1 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 1 |

| Increased Pain | 22 | 16 |

| Redness/Infection | 1 | 0 |

| Muscle Soreness | 6 | 2 |

| Swelling | 6 | 5 |

| Tearfulness | 0 | 1 |

| Weakness | 1 | 0 |

| Other | 7 | 5 |

|

| ||

| Total | 47 | 31 |

| Withdrawals | True Acupuncture | Non-penetrating Acupuncture |

|---|---|---|

| Loss to follow-up | 8 | 7 |

| Adverse events | 3 | 0 |

| Protocol violations | 2 | 2 |

| Patient withdrew | 4 | 6 |

|

| ||

| Total | 17 | 15 |

Since acupuncture is conducted in the same setting of Exercise-based physical therapy (EPT), whether such side effect relates to acupuncture or EPT may be difficult to assess.

Statistical Analyses

Demographics

Standard descriptive statistics were used to evaluate all baseline characteristics. Summary statistics were used for means, medians, and proportions to assess differences between the treatment groups. Graphical methods were used to examine distributions and to assess the need for data transformations.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome analysis was an intention-to-treat comparison between the groups. Baseline observation carry forward was used for any missing data. The unadjusted comparison between the treatment groups was analyzed using a chi square test for the primary dichotomous outcome (WOMAC total change >36%).

For secondary analyses, data for continuous variables are presented as mean with a 95% confidence limit; and the 2-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare treatment arms. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions in the two groups.

A logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between baseline characteristics of the population and the outcomes. Characteristics significant at the 0.10 level were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model, where both stepwise and forward selection (criteria of p= 0.2 to enter the model and p= 0.05 to stay in the model) were used to develop a multivariable model to predict response. All analyses were two-sided using SAS 9.2 (SAS Incorporated, Cary, NC).

Sample size estimate

The original study was designed to detect a difference of 15% in response between patients getting real and non-puncturing acupuncture, with an estimate of 50% improvement in the control group. We estimated that 169 patients per group would be necessary to detect this difference. With a slower-than-expected accrual, we chose to examine the data for futility, blinded to group treatment, with 65% of the patients collected, which was confirmed and the study was stopped.

Role of the funding source

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine provided funding for this study. The agency had no role in the design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data.

RESULTS

Recruitment

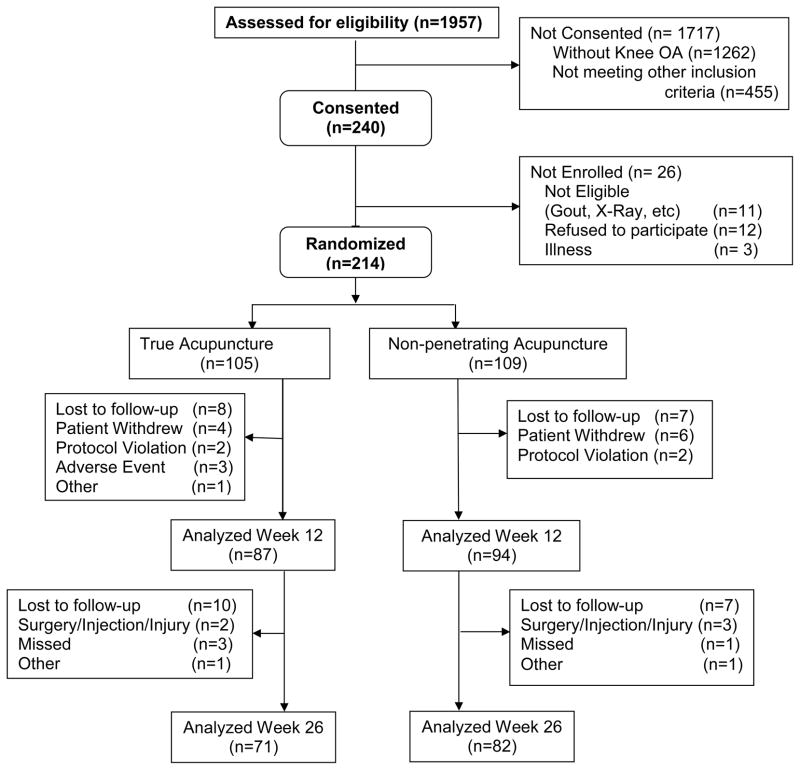

Out of a total of 1,957 patients evaluated for the study, 1,262 presented to EPT for reasons other than knee OA and 455 did not meet study criteria on initial screening or refused to participate. Of the 240 consented by the study coordinators, 11 were excluded for not meeting X-ray diagnosed criteria, 12 patients chose not to continue in the study, and 3 did not attend further EPT due to illness. A total of 214 eligible patients were randomized between January 2000 and December 2006 (Figure 1). The median number of EPT/acupuncture sessions was 11, with 81% of subjects attending more than 8 sessions, and 28% completing all 12 treatments (See Figure 1). We stopped the trial with 214 subjects given the results were highly negative, with 31.6% response rate for the standard acupuncture, and 30.3% for the non-puncturing acupuncture. Our original design was to collect 169 subjects per group to achieve 80% power to detect a 15% difference in response rates. Using a futility analysis, if we were to continue collecting the remaining 62 subjects for each group assuming the response rate of the control group to remain the same at 30.3%, the response rate of the remaining 62 subjects in the standard treatment group would have had to reach 71% in order to produce an overall 15% between-group difference. This means that the remaining 62 subjects in the treatment group would have had to be from a totally different population compared with the first 107 subjects (p<0.001). This amount of difference is highly unlikely.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the disposition of all study participants in the real and placebo acupuncture groups, with the reason for any drop-outs from screening through 26 weeks.

Baseline Data

Of the 214 eligible patients, 141 (66%) were African Americans; 111 (52%) were female, and the mean age was 60. The mean BMI was 33 (SD - 7) with 64 (30%) participants having a BMI greater than 35. The average duration of knee symptoms was almost 10 years. Approximately 50% of participants reported that they thought that acupuncture would help their knee OA symptoms, and the rest reported acupuncture “may be helpful.” No participants reported that acupuncture would not help. Only the 6 minute walk distance was statistically significantly different, between the groups. No pretreatment differences were found to be clinically relevant among the two experimental groups in any socio-demographic or other clinical factors. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics* | Non- penetrating Acupuncture N=109 | True Acupuncture N=104 | p-Value Non-penetrating/True |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

|

| |||

| Age | 60.4 (11.7) | 60.5 (11.1) | 0.934 |

| Female | 57 (52.3%) | 53 (51%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 34 (31.2%) | 28 (26.9%) | 0.629 |

| African American | 69 (63.3%) | 72 (69.2%) | |

| Other | 6 (5.5%) | 4 (3.8%) | |

| Currently Married | 37 (33.9%) | 40 (38.5%) | 0.493 |

| Work Outside the Home | 34 (31.2%) | 30 (28.8%) | 0.709. |

|

| |||

| Clinical | |||

|

| |||

| BMI* (Mean kg/m2 (95% CL)) | 32.6 (31.2, 33.9) | 33.3 (31.8, 34.9) | 0.690 |

| <=35 (n, %) | 75 (70.1%) | 67 (69.8%) | |

| >35 (n, %) | 32 (29.9%) | 29 (30.2%) | |

| Kellgren (Worst Knee) | |||

| 2 | 47 (43.1%) | 38 (36.5%) | 0.243 |

| 3 | 62 (56.9%) | 66 (63.5%) | |

| Pain Duration (Yrs) | 9.4 (9.2) | 9.6 (9.9) | 0.997 |

| WOMAC | 44.0 (15.7) | 47.6 (14.7) | 0.097 |

| BPI | 5.7 (1.9) | 5.6 (2.0) | 0.528 |

| 6 Min Walk Distance (meter) | 1126 (289) | 1032 (314) | 0.021 |

|

| |||

| Psychological | |||

|

| |||

| Perceived Helpfulness | |||

| Maybe | 57 (52.3%) | 52 (50%) | 0.738 |

| Yes | 52 (47.7%) | 52 (50%) | |

Abbreviation: BMI=body mass index; Yrs=Years; BPI=Brief Pain Inventory, Min=minutes

The African-American subjects were predominantly female, less often married, and with a higher BMI than their Caucasian counterparts. Their WOMAC and 6 minute walk distance were worse. A higher percentage tended to think that acupuncture would help them but this was not statistically significant (p=0.349).

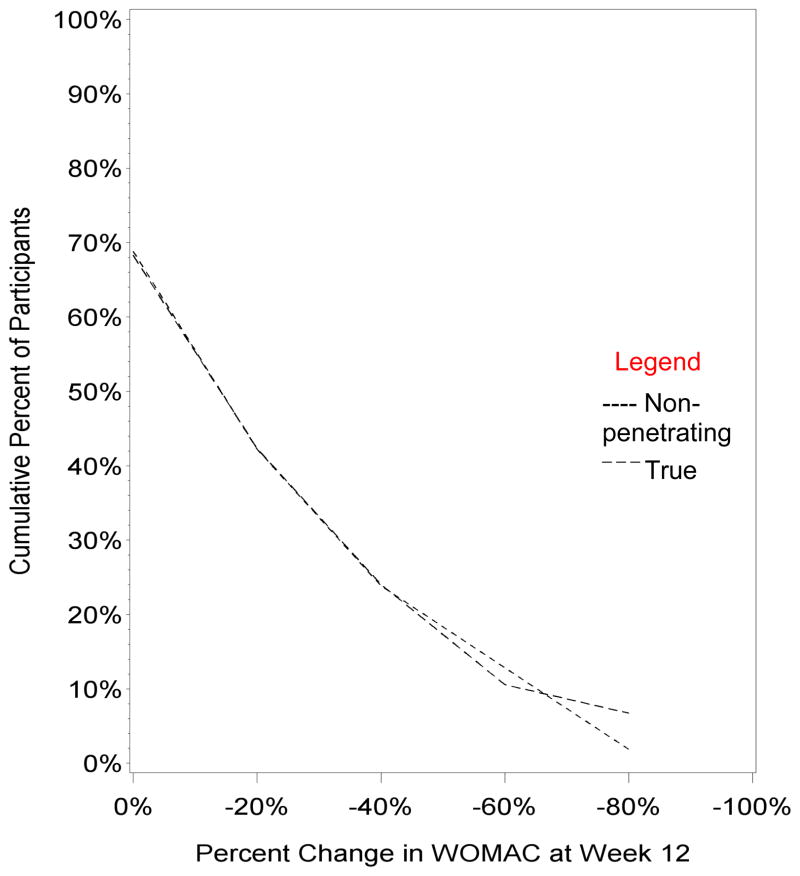

Outcome Assessment

In the context of EPT, the observed success rates (defined as at least 36% improvement in WOMAC scores) were essentially identical with 31.6% for the true acupuncture and 30.3% for the non-penetrating acupuncture at week 12, p=0.5 (Table 2). Between baseline and week 12, both interventions were associated with an 18–19% mean improvement in WOMAC total score (p=0.27 for the two group comparison) and 24% mean improvement in BPI (p=0.52 for the two group comparison). At the end of the intervention, 74% of patients considered their knee OA symptoms to be at least slightly better, 38% at least better, 13% much better. No outcomes differed at any interval of evaluation. Based on the cumulative distribution function curves[28] displaying every possible definition of a clinical response on the WOMAC, no appreciable clinical or statistical differences were observed (Figure 2). All secondary outcomes were also examined and showed no separation between the treatment groups. An identical series of analyses were carried out for subgroups by race, with essentially identical negative results.

Table 2a.

Primary Outcomes, Differences between Groups, and Changes over Time*

| Primary Randomized Outcome Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variable | Non-Penetrating Acupuncture (N=109) | True Acupuncture (N=104) | p-value |

| Success Rate (WOMAC@36%), n(%) | |||

|

| |||

| Week 12 | 30 (27.5%) | 27 (26.0%) | 0.86 |

| Week 26 | 16 (14.7%) | 16 (15.4%) | 0.85 |

|

| |||

| WOMAC Total Score | |||

|

| |||

| Mean at baseline | 44.0 (41.0, 46.9) | 47.6 (44.8, 50.5) | 0.080 |

| at 12 weeks | 33.6 (30.0, 37.2) | 37.0 (33.2, 40.9) | 0.193 |

| at 26 weeks | 37.2 (32.8, 41.6) | 41.5 (37.6, 45.4) | 0.148 |

| Mean individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −10.0 (−12.7, −7.3) | −10.8 (−14.2, −7.4) | 0.717 |

| at 26 weeks | −5.42 (−8.17, −2.67) | −6.44 (−9.77, −3.11) | 0.638 |

| Mean % individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −22% (−28%, −15%) | −21%(−29%, −14%) | 0.939 |

| at 26 weeks | −13% (−21%, −5%) | −12% (−19%, −5%) | 0.819 |

|

| |||

| WOMAC Pain Score Subscale | |||

|

| |||

| Mean at baseline | 9.47 (8.83, 10.1) | 10.31 (9.65, 11.0) | 0.070 |

| at 12 weeks | 6.93 (6.16, 7.70) | 7.51 (6.63, 8.39) | 0.321 |

| at 26 weeks | 7.79 (6.83, 8.75) | 8.56 (7.77, 9.35) | 0.227 |

| Mean Individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −2.35 (−2.96, −1.74) | −2.83 (−3.71, −1.94) | 0.370 |

| at 26 weeks | −1.35 (−2.05, −0.64) | −1.91 (−2.63, −1.18) | 0.272 |

| Mean % change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −22% (−31%, −14%) | −25% (−34%, −17%) | 0.641 |

| at 26 weeks | −13% (−23%, −4%) | −16% (−24%, −9%) | 0.674 |

|

| |||

| WOMAC Function Score Subscale | |||

|

| |||

| Mean at baseline | 30.3 (28.1, 32.6) | 32.9 (30.8, 35.0) | 0.104 |

| at 12 weeks | 23.2 (20.5, 25.9) | 26.0 (23.1, 28.8) | 0.158 |

| at 26 weeks | 25.7 (22.4, 28.9) | 29.0 (26.0, 31.8) | 0.132 |

| Mean Individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −6.93 (−8.99, −4.87) | −7.02 (−9.55, −4.49) | 0.956 |

| at 26 weeks | −3.74 (−5.76, −1.72) | −4.02 (−6.59, −1.46) | 0.860 |

| Mean % change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −22% (−29%, −14%) | −20% (−28%, −11%) | 0.765 |

| at 26 weeks | −14% (−22%, −5%) | −9% (−18%, −1%) | 0.491 |

|

| |||

| WOMAC Stiffness Score Subscale | |||

|

| |||

| Mean at baseline | 4.16 (3.84, 4.48) | 4.42 (4.11, 4.73) | 0.238 |

| at 12 weeks | 3.40 (3.10, 3.69) | 3.57 (3.24, 3.90) | 0.427 |

| at 26 weeks | 3.78 (3.38, 4.19) | 3.99 (3.59, 4.38) | 0.475 |

| Mean Individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −0.75 (−1.10, −0.40) | −0.94 (−1.29, −0.59) | 0.439 |

| at 26 weeks | −0.35 (−0.77, 0.08) | −0.51 (−0.88, −0.13) | 0.586 |

| Mean % change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −15% (−24%, −5%) | −17% (−25%, −9%) | 0.718 |

| at 26 weeks | −8% (−18%, 1%) | −5% (−15%, 5%) | 0.666 |

Abbreviation: BMI=body mass index; Yrs=Years; BPI=Brief Pain Inventory, Min= minutes

Figure 2.

Cumulative distribution of the proportion of participants achieving the level of response as a percentage change in the WOMAC score from baseline to week 12.

Safety

Overall, the acupuncture process was found to be safe. Seventy-eight adverse events were elicited among 214 subjects over the course of over 2,000 acupuncture and placebo acupuncture treatments, with no difference by race. Most were mild events and few resulted in discontinuation of therapy. A few more events were reported with true needling acupuncture versus placebo acupuncture, which approached a statistically significant difference (n=47 vs. 31 p=0.08). The most commonly reported side effects were increased pain (n=38), muscle soreness (n=8), and swelling (n=11) (Table 3). Because acupuncture was given immediately following EPT, it was not always possible to associate the event with acupuncture or EPT separately.

Predictors of Response

In multivariate logistic regression modeling combining both patient groups and adjusting for all covariates that met criteria, those who anticipated acupuncture to be definitely helpful were significantly more likely to report that they responded to therapy with an adjusted odds ratio (AOR, 95% CI) of 2.14 (1.13–4.10), p=0.02. Higher baseline 6-minute walk distance was also associated with significant success AOR 1.14 (1.02 – 1.29), p=0.026 for every 100-foot incremental increase (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of Response to Acupuncture and EPT Regimens

| All Races - Combined Treatment Groups

|

Univariate | Multivariate Model* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

| Duration of Pain in Years | 0.98 (0.94– 1.01) | 0.18 | Dropped | NS |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status (Married - Reference) | 1 | |||

|

| ||||

| Currently Not Married | 1.65 (0.85– 3.2) | 0.14 | Dropped | NS |

|

| ||||

| BPI Baseline | 1.12 (0.95– 1.3) | 0.18 | Dropped | NS |

|

| ||||

| 6-min Walk Distance (Unit=100 feet) | 1.10 (0.99– 1.2) | 0.08 | 1.14 (1.02 – 1.29) | 0.027 |

|

| ||||

| Perceived Helpfulness | ||||

|

| ||||

| Acupuncture (Maybe Helpful - reference) | 1 | 1 | ||

|

| ||||

| Definitely Helpful | 2.0 (1.08– 3.7) | 0.028 | 2.15 (1.13 – 4.10) | 0.014 |

Abbreviations: Odds ratio (OR), Confidence Interval (CI), Minute (Min)

Univariate unadjusted model predicting response using factors with a p-value ≤ 0.2 for comparison between groups.

Multivariate model adjusted for race, age, and sex. Remaining factors: Walking distance per 100 feet, and patients’ perceived helpfulness of acupuncture

BMI and Treatment Interaction

The patients enrolled in this study were significantly more obese than earlier studies, with preponderance in the African-American group. In secondary exploratory analysis, we identified significant BMI (≤35 vs. >35) and treatment true vs. non-penetrating) interaction (p=0.01 for the interaction term) adjusting for baseline WOMAC score, age, sex, and race. In the BMI ≤35 group (N = 142), no significant WOMAC response difference was seen between real and control acupuncture (22.8% vs. 33.8%, p=0.18); however, in the BMI >35 group (N = 61), the real acupuncture group had significantly more responders than the placebo acupuncture group (52.0% vs. 23.1%, p=0.03) (Figure 4).

Masking Effectiveness

At the end of the intervention, most participants in the real and placebo acupuncture groups believed that they were receiving real acupuncture (76% vs. 67%); most of the remainder were unsure (20% vs. 24%), respectively (p=0.36).

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the efficacy of true acupuncture versus acupuncture with a non-puncturing needle integrated with standardized exercise-based physical therapy (EPT) for the treatment of knee OA in a racially mixed group of patients with a mean BMI of 33. No differences between the true and non-penetrating acupuncture groups were demonstrated for any of the primary or secondary end points. Across both treatment groups, subjects experienced improvement over the course of their therapy.

Secondary analyses showed that a priori positive expectation for the efficacy of acupuncture was strongly predictive of treatment success. The patient’s walking ability at baseline was also statistically significant but had only a very small total effect. We also found a potentially interesting interaction between the degree of obesity and the treatment outcome, with heavier patients (BMI > 35) receiving real acupuncture improving significantly more than those receiving placebo acupuncture. However, this subgroup analysis was not defined a priori so this result should be considered hypothesis generating and would need further evaluation. One possibility is that after this trial is contributed to the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration individual patient data meta-analysis project, this association could be examined across all acupuncture trials.

The lack of differences between the true versus the non-penetrating needle group is not totally unexpected. Recent studies and systematic reviews have found modest differences, if any, between true acupuncture and different sham and placebo controls[3, 4, 6–11]. Our study similarly provides evidence for the lack of specificity of the puncturing component of the therapy. Given our control of a non-puncturing needle applied to the appropriate acupuncture points, we cannot rule out the possibility that the tactile stimulation of the skin may have activated cutaneous afferent nerve endings, as has been postulated for “acupressure,”[29] improving overall function, albeit to an extent similar to that reported by the real acupuncture group.

Our data support the overall benefit of providing a therapy or combination of therapies in which the patient has confidence, including the important role of expectation on the impact of a non-specific effect on the outcome. In the analysis of our full dataset, we found that those patients who reported thinking acupuncture would definitely help them (“positive expectancy”) had a 2-fold increase in the likelihood of reporting a positive response, which was equally true in both racial groups. This is in agreement with other studies that emphasized the correlation of improvement with high expectations[9, 14, 15]. This is also consistent with reviews[30] and with a recent German study that examined expectancy in pooled data from several large acupuncture trials for chronic pain[13]. We could not compare response to patients who thought that acupuncture would not help, since patients who felt negatively about acupuncture were unlikely to enroll. It is also possible that the patient’s interest in receiving acupuncture improved their performance in the exercise component of the trial, or was associated with attendance at a higher number of EPT sessions, as suggested in other research [3]. We do not have such data from our trial. Matching the patient’s expectation with a clinically effective therapy might have the potential to improve arthritis care.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The lack of a physical therapy only group did not allow an estimate of whether the combination with acupuncture was better or worse than the EPT alone, but overall patients reported improvement with their therapies and the amount of improvement was greater in those who expected the acupuncture to work. Our study with greater numbers of treatments is in considerable agreement with a study providing only 6 sessions over 3 weeks of true and sham acupuncture regimens added to physiotherapy for OA of the knee. This latter study produced no additional benefit at 6 months although findings suggested that there may have been some attenuation of pain with both types of acupuncture at 2 and 6 weeks[19]. We did not reach our proposed sample size due to the slower than expected recruitment; however, a futility analysis demonstrated that we would not have found a difference in our groups even if the full sample size had been obtained. Although 26 weeks was a secondary end point, 29% of subjects did not provide evaluable week 26 data, which could have biased our analysis at that time point but is unlikely to have changed our results.

In our study acupuncture therapy was provided immediately following the EPT. It is possible that the exercise therapy, which is known to produce a positive effect[31] may have made the evaluation of an additional specific benefit from acupuncture more difficult (i.e., the law of diminishing returns), but if so the acupuncture effect would be small and of questionable clinical importance. Studies that test the efficacy of the entire process of the administration of acupuncture are more likely to find a positive result, such as the positive findings of Berman et al. in the comparison of acupuncture to no acupuncture[19].

Our acupuncturists reported achieving a de qi sensation in some of the real acupuncture needle patients, we did not formally record the sensations reported by the patient, so we do not know how often this occurred in either group of patients. Experience in the original validation studies [21, 32] and a more recent RCT of acupuncture for osteoarthritis[33], found a substantial number of participants in the sham control group reported sensations consistent with a description of the de qi raising concerns about the inert nature of the sham. Since the beginning of this study there has been a significant discussion of this issue in the literature. Clearly, it is possible that a reason for the identical results in both the real and sham acupuncture groups is that both are active but our study cannot address this issue specifically.

Lastly, we did not test to see if the timing of the acupuncture could affect the outcome. Might acupuncture before the EPT have facilitated the EPT by alleviating pain? Some recent work in rodent models suggests that acupuncture may involve connective tissue displacement and remodeling.[34, 35] If EPT changes the effect of the puncturing needle on local connective tissue, it may have reduced the effect. As acupuncture is frequently used concurrently with conventional care, studies of the timing of integration may be an area to explore in order to better understand the contributions of the combined effects of different therapies.

A recent individual patient meta-analysis[36] and an accompanying editorial[37] on studies of acupuncture used for a variety of types of pain concluded that true acupuncture was modestly more effective than a variety of different types of sham acupunctures. These also highlighted the limitations of studies and suggested that factors in addition to specific effects of needling can be important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture.

Despite the limitations, we have conducted a large acupuncture clinical trial in a population with a broad spectrum of body habitus and a large African-American component. We did not find any differences in effect of the puncturing and nonpuncturing acupuncture therapy when used in conjunction with EPT. Our study also highlights that positive expectation may impact treatment outcomes.

Table 2b.

Secondary Outcomes, Differences between Groups, and Changes over Time*

| Secondary Randomized Outcome Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variable | Placebo Acupuncture (N=109) | True Acupuncture (N=104) | p-value |

| BPI Average Pain | |||

|

| |||

| Mean at baseline | 5.70 (5.34, 6.06) | 5.69 (5.29, 6.09) | 0.454 |

| at 12 weeks | 3.93 (3.52, 4.34) | 4.03 (3.58, 4.48) | 0.703 |

| at 26 weeks | 4.69 (4.23, 5.15) | 4.54 (4.03, 5.04) | 0.780 |

| Mean Individual change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −1.73 (−2.22, −1.24) | −1.48 (−2.01, −0.95) | 0.427 |

| at 26 weeks | −1.05 (−1.57, −0.53) | −0.96 (−1.60, −0.31) | 0.774 |

| Mean % change | |||

| at 12 weeks | −24% (−33%, −15%) | −24% (−34%, −15%) | 0.522 |

| at 26 weeks | −13% (−25%, −1%) | −15% (−26%, −3%) | 0.718 |

|

| |||

| SF-36 Physical Subscale | |||

|

| |||

| Mean baseline score | 32.1 (30.5, 33.7) | 31.7 (30.2, 33.3) | 0.201 |

| Mean score at 12 weeks | 36.9 (34.8, 38.9) | 35.4 (33.5, 37.3) | 0.609 |

| Mean change at 12 weeks | 4.30 (2.61, 6.00) | 3.01 (1.09, 4.93) | 0.353 |

| Mean % change at 12 weeks | 16.1% (10.2%, 22.1%) | 12.8% (6.0%, 19.6%) | 0.312 |

|

| |||

| SF-36 Mental subscale | |||

|

| |||

| Mean baseline score | 49.7 (47.2, 52.2) | 46.2 (43.8, 48.5) | 0.029 |

| Mean score at 12 weeks | 53.9 (51.8, 56.0) | 52.0 (49.5, 54.6) | 0.169 |

| Mean change at 12 weeks | 3.33 (1.30, 5.24) | 5.01 (2.88, 7.15) | 0.848 |

| Mean % change at 12 weeks | 10.5% (5.5%, 15.5%) | 14.8 (9.00%, 20.6%) | 0.999 |

|

| |||

| 6 Minute Walk Test (in feet) | |||

|

| |||

| Mean baseline score | 1126 (1070, 1182) | 1032 (970, 1094) | 0.027 |

| Mean score at 12 weeks | 1147 (1086, 1209) | 1119 (1046, 1195) | 0.562 |

| Mean change at 12 weeks | 38.5 (−7.04, 84.0) | 55.5 (1.10, 109.1) | 0.633 |

| Mean % change at 12 weeks | 8% (−1%, 17%) | 9% (2%, 16%) | 0.847 |

|

| |||

| Patient Global Assessment | |||

|

| |||

| ≥ “Slightly better” at 12 weeks | 79 (72.5%) | 78 (75%) | 0.676 |

| ≥ “Slightly better” at 26 weeks | 52 (62.7%) | 52 (69.3%) | 0.738 |

| ≥ “Better” at 12 weeks | 44 (40.4%) | 36 (34.6%) | 0.386 |

| ≥ “Better” at 26 weeks | 27 (32.5%) | 24 (32%) | 0.772 |

| ≥ “Much better” at 12 weeks | 17 (15.6%) | 11 (10.6%) | 0.278 |

| ≥ “Much better” at 26 weeks | 12 (14.5%) | 9 (12%) | 0.564 |

Abbreviation: BMI=body mass index; Yrs=Years; BPI=Brief Pain Inventory, Min=minutes

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the hard work of the physical therapists, acupuncturists, coordinators and support staff. This includes: Lorna Lee; Dell Burkey, MD; Patricia Williams, RN; Erin McMenamin, RN, NP; Maryte Papadopoulos; Andrea Cheville, MD; Meryl Stein, MD; Gurneet Singh, Lic Acu.; Debra Braverman, MD; Penn-Therapy Physical Therapy Group.

This study is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) R01-AT000304. Dr. Mao is also supported by NCCAM K23 AT004112. The funding agency had no role in the design and conduct of this study. The principal investigator has full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00035399

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending that are in conflict with this publication.

References

- 1.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;(343):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(12):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okoro CA, Zhao G, Li C, Balluz LS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among US adults with and without functional limitations. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(2):128–35. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.591887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manheimer E, Linde K, Lao L, Bouter LM, Berman BM. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):868–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White A, Foster NE, Cummings M, Barlas P. Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(3):384–90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, Basler HD, Schafer H, Maier C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(17):1892–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, Lao L, Yoo J, Wieland S, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotle M. Traditional Chinese acupuncture was not superior to sham acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis but delivering treatment with high expectations of improvement was superior to delivering treatment with neutral expectations. Journal of physiotherapy. 2011;57(1):56. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derry CJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Systematic review of systematic reviews of acupuncture published 1996–2005. Clin Med. 2006;6(4):381–6. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-4-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezzo J, Hadhazy V, Birch S, Lao L, Kaplan G, Hochberg M, et al. Acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(4):819–25. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<819::AID-ANR138>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawker GA, Mian S, Bednis K, Stanaitis I. Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: non-pharmacologic therapy. Osteoarthritis and cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2011;19(4):366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, Witte S, Kramer J, Maier C, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(1):12–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, Brinkhaus B, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2007;128(3):264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Street RL, Jr, Cox V, Kallen MA, Suarez-Almazor ME. Exploring communication pathways to better health: clinician communication of expectations for acupuncture effectiveness. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(2):245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witt CM, Schutzler L, Ludtke R, Wegscheider K, Willich SN. Patient characteristics and variation in treatment outcomes: which patients benefit most from acupuncture for chronic pain? Clin J Pain. 2011;27(6):550–5. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31820dfbf5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galantino ML, Sowers K, Kelly M, Mao J, LaRiccia P, Farrar J. Acupuncture as an Adjuvant Modality With Physical Therapy for Patients With Knee Osteoarthritis. Medical Acupuncture. 2009;21(3):157–66. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szebenyi B, Hollander AP, Dieppe P, Quilty B, Duddy J, Clarke S, et al. Associations between pain, function, and radiographic features in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):230–5. doi: 10.1002/art.21534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacPherson H, White A, Cummings M, Jobst KA, Rose K, Niemtzow RC, et al. Standards for Reporting Interventions in Controlled Trials of Acupuncture: the STRICTA recommendations. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8(1):85–9. doi: 10.1089/107555302753507212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berman BM, Lao L, Langenberg P, Lee WL, Gilpin AM, Hochberg MC, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture as adjunctive therapy in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(12):901–10. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Armstrong K, Donahue A, Ngo J, Bowman MA. De qi: Chinese acupuncture patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding acupuncture needling sensation--an exploratory survey. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(4):158–65. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.4.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streitberger K, Kleinhenz J. Introducing a placebo needle into acupuncture research. Lancet. 1998;352(9125):364–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldsmith CH, Boers M, Bombardier C, Tugwell P. Criteria for clinically important changes in outcomes: development, scoring and evaluation of rheumatoid arthritis patient and trial profiles. OMERACT Committee. The Journal of rheumatology. 1993;20(3):561–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldsmith CH, Duku E, Brooks PM, Boers M, Tugwell PS, Baker P. Interactive conference voting. The OMERACT II Committee. Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trial Conference. The Journal of rheumatology. 1995;22(7):1420–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–58. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2008;9(2):105–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrar JT, Dworkin RH, Max MB. Use of the cumulative proportion of responders analysis graph to present pain data over a range of cut-off points: making clinical trial data more understandable. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2006;31(4):369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lund I, Naslund J, Lundeberg T. Minimal acupuncture is not a valid placebo control in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture: a physiologist’s perspective. Chinese medicine. 2009;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vas J, White A. Evidence from RCTs on optimal acupuncture treatment for knee osteoarthritis--an exploratory review. Acupunct Med. 2007;25(1–2):29–35. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.1-2.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deyle GD, Henderson NE, Matekel RL, Ryder MG, Garber MB, Allison SC. Effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise in osteoarthritis of the knee. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):173–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-3-200002010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC, Mackenzie ER, et al. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(4):50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster NE, Thomas E, Barlas P, Hill JC, Young J, Mason E, et al. Acupuncture as an adjunct to exercise based physiotherapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2007;335(7617):436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39280.509803.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langevin HM, Bouffard NA, Badger GJ, Churchill DL, Howe AK. Subcutaneous tissue fibroblast cytoskeletal remodeling induced by acupuncture: evidence for a mechanotransduction-based mechanism. Journal of cellular physiology. 2006;207(3):767–74. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langevin HM, Churchill DL, Wu J, Badger GJ, Yandow JA, Fox JR, et al. Evidence of connective tissue involvement in acupuncture. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2002;16(8):872–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0925fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1444–53. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avins AL. Needling the status quo. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1454–5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]