Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Concerns over rising drug costs, pharmaceutical advertising and potential conflicts of interest have focused attention on physician prescribing behavior. We examine how broadly physicians prescribe within the ten most prevalent therapeutic classes, the factors affecting their choices, and its impact on patient-level outcomes.

STUDY DESIGN

Retrospective study from 2005 to 2007 examining prescribers with at least five initial prescriptions within a class from 2005–2007. Medical and pharmacy claims are linked to prescriber information from 146 different health plans, reflecting 1,975 to 8,923 unique providers per drug class.

METHODS

Primary outcomes are the number of distinct drugs in a class initially prescribed by a physician over 1- and 3-year periods, medication possession ratio, and out of pocket costs.

RESULTS

In 8 of 10 therapeutic classes, the median physician prescribes at least 3 different drugs and less than one in six physicians prescribes only brand drugs. Physicians prescribing only one or two drugs in a class are more likely to prescribe the most advertised drug. Physicians who prescribe fewer drugs are less likely to see patients with other comorbid conditions and varied formulary designs. Prescribing fewer drugs is associated with lower rates of medication adherence and higher out-of-pocket costs for drugs, but the effects are small and inconsistent across classes.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians prescribe more broadly than commonly perceived. Though narrow prescribers are more likely to prescribe highly advertised drugs, few physicians prescribe these drugs exclusively. Narrow prescribing has modest effects on medication adherence and out of pocket costs in some classes.

Keywords: Physician prescribing, Drug promotion

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, pharmaceutical firms spent over $57 billion on marketing in the US, roughly twice their expenditures on research and development [1]. Most of this spending targeted physicians through sales representatives (detailing), sampling (provision of drugs at no cost), physician meetings and advertisements in medical journals [2]. For example, industry sponsored promotional events increased from 120,000 in 1998 to 371,000 events in 2004 [3]. There has also been a significant increase in the frequency and size of federal and state penalties for illegal promotion of drugs and pricing irregularities [1].

These trends have raised concern that pharmaceutical companies might have undue influence on the prescribing behavior of physicians. In particular, there is concern that a significant fraction of physicians might be prescribing a narrow range of heavily promoted drugs or might be exclusively prescribing branded drugs to the detriment of patient welfare. However, empirical evidence on the prescribing behavior of physicians and its consequences for patients is limited. Some studies suggest that physicians prescribe narrowly, particularly general practitioners, but much of this evidence is decades old. [4]; [5]; [6]; [7]; [8]. More recent work finds that the prescribing patterns of physicians are substantially more concentrated than the aggregate market in each class, and that physicians differ in their preferred drug within a class [9]; [10].

While theory suggests that habitual prescribing can be both clinically suboptimal and economically wasteful, the appropriateness of broad versus narrow prescribing is likely to depend on the composition of the drug class. Narrow prescribing may be optimal when one drug is clearly superior to the others, or if all the drugs in the class act in a similar way. For example, prescribing only a generic or low cost brand in a largely homogenous class may be beneficial given that lower patient cost-sharing is associated with improved adherence [11]; [12]; [13]. In addition, most generics are inherently safer than newer drugs because of their longer track record in clinical practice and known side-effects [14]; [15]. Alternatively, some classes are characterized by heterogeneous effects, where a specific drug provides therapeutic benefit to some patients and little to others, or has known side effects that are problematic for a subset of patients. If the heterogeneous benefits and side effects of these drugs are known ex-ante, a better informed physician will prescribe more broadly, taking into account the specific medical characteristics of each patient. Taub and colleagues find that psychiatrists prescribe more broadly than general practitioners within the atypical antipsychotic class, but they cannot determine how much of the difference is explained by variation in the case-mix of patients seen by psychiatrists versus non-specialists [9].

Beyond the challenge of predicting a drug’s therapeutic value to a new patient, an unrelated factor further complicates the prescribing decision: plan formularies. Most drug classes today include an array of similar products that compete for essentially the same population of patients, and health plans typically choose a small subset of these products to offer at low cost-sharing rates. In addition, direct-to-consumer advertising has emboldened patients to request specific treatments [16]; [17]; [18]. How these factors have affected physicians’ choice of drug therapies is uncertain.

In this paper, we examine the breadth of physician prescribing in ten large drug classes with several similar-acting agents. We measure the number and type (generic or brand) of different drugs prescribed as initial prescriptions by each physician and the factors that affect their choices. We then examine whether broad or narrow prescribing is associated with patient-level outcomes such as rates of medication adherence, therapeutic switching, and out-of-pocket drug spending. We know of no other study that examines the relationship between how broadly physicians prescribe and patient-level outcomes (adherence, medical care use) that can proxy for clinical measures.

METHODS

Data

We use unique data matching prescriptions to prescribing physicians. The data include medical and pharmaceutical claims from 29 large employers in the United States from 2003 to 2007. The drug claims include information on the type of drug, drug name, national drug code, dosage, days supplied, and place of purchase (retail or mail order). Starting in 2005, all pharmacy claims identify the prescriber by masked DEA number. Thus from 2005–2007, we can observe prescriptions made by the same physician to different patients in different insurance plans. We do not have any additional information about the prescribers. To be eligible for the sample, a patient must be at least 18 years old and continuously enrolled for at least one year before initiating therapy, and for at least six months afterwards.

We use the IMS Advertising Database to measure the degree of drug promotion for each product. The advertising data are reported quarterly and contain expenditures on direct-to-consumer and direct-to-physician advertising for each drug, including medical journal advertisements, promotional visits to physicians and drug samples.

Measurement

We use a common classification scheme—the 2007 Red Book published by Thomson—to associate each drug with a therapeutic class. Table 1 shows the 10 most common therapeutic classes (in terms of dollars spent) in our sample for 2005. These are cholesterol-reducing drugs, antidepressants, non- H2A stomach drugs, antihistamines, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors, and antidiabetic drugs excluding insulin. To further narrow down the classes, we focus on statins within cholesterol-reducing drugs (dropping ezetimbe, fibrates and others), on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine inhibitors (SNRIs) within antidepressants (keeping bupropion formulations, dropping tricyclic antidepressants), and on proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) within non- H2A stomach drugs. In the antihistamine class, we drop promethazine which is prescribed primarily as an acute treatment and often used as a sedative or antiemetic rather than for allergy treatment. We define an initial prescription as the absence of any pharmacy claim in the same therapeutic class for at least twelve months.

Table 1.

Distribution of Brand and Generic Prescribing in 10 Therapeutic Classes, Initial Prescriptions Only

| Therapeutic Class | Generic Prescribing Share | Percent of Prescribers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors Prescribing ONLY Generics | Doctors Prescribing ONLY Brands | Doctors Prescribing Brands and Generics | ||

|

| ||||

| ACE Inhibitors | 86.3 | 53.8 | 0.7 | 45.5 |

| SSRI/SNRI | 44.6 | 3.0 | 8.4 | 88.6 |

| Antihistamines | 37.8 | 2.1 | 14.0 | 84.0 |

| Beta Blockers | 57.1 | 11.5 | 3.0 | 85.5 |

| Calcium Channel Blockers | 40.3 | 2.7 | 9.7 | 87.6 |

| Antidiabetics | 61.3 | 15.9 | 3.9 | 80.2 |

| NSAID | 83.9 | 39.1 | 0.9 | 60.0 |

| Opiates | 98.6 | 89.7 | 0.0 | 10.3 |

| PPIs | 20.9 | 0.9 | 34.8 | 64.3 |

| Statins | 23.8 | 0.6 | 27.6 | 71.9 |

Since most plans assign lower copayments to generic drugs, and often charge the same copayment for all generics, narrow prescribing is most likely to impact average costs in classes where brand drugs are dominant. For this reason, some analyses focus on the five drug classes in which more than 50 percent of initial prescriptions are for brand drugs: statins, SSRI/SNRIs, PPIs, antihistamines, and calcium channel blockers. We call these the “brand-dominated” classes.

In three of these classes, one major drug became newly available as a generic during the study period: simvastatin (statin, starting June 2006), sertraline (SSRI, June 2006), and fexofenadine (antihistamine, September 2005). In the calcium channel blocker class, two generics entered the market towards the end of our study period (2007): amlodipine in March and amlodipine/benazepreil in May. In measuring the number of drugs prescribed, we treat brand and generic formulations of a multisource product as different drugs. However, the results are not sensitive to this choice.

We restrict the sample to physicians with at least five initial prescriptions within a class from 2005–2007. We focus on initial prescriptions since refills may reflect the prescribing decisions of other providers. This yields a sample of 74,163 initial statin prescriptions, prescribed by 8,923 unique providers. The corresponding prescription/provider counts for the other brand-dominant classes are PPIs (52,978/6,621), SS/NRI (46,040/5,866), antihistamines (39,644/4,788), and calcium channel blockers (13,633/1,975). We categorize providers within each class by the number of distinct drugs prescribed as initial prescriptions over the sample period (2005–2007). For example, a doctor with two initial prescriptions of escitalopram, three initial prescription of sertraline, and one initial prescription of duloxetine is categorized as prescribing three drugs in the SS/NRI class.

Given that new drugs may enter the market and additional clinical evidence may emerge over the 3-year study period, we also categorize physicians based on the number of distinct drugs prescribed each year. This reduces our sample substantially as two-thirds to three-quarters (depending on the class) of physicians in the 3-year sample do not have five initial prescriptions within a calendar year. To facilitate comparison with other studies of prescribing concentration, we also calculate the share of prescriptions for each physician’s “favorite” drug.

Statistical Analyses

We examine use of the top-selling and most heavily promoted drugs in the class, as well as rates of generic drugs by prescriber type. We also calculate the share of a physician’s observed prescriptions that are in the relevant therapeutic category (e.g. cardiovascular drugs for statin prescriptions) as a proxy for their degree of specialization.

To assess factors that influence a physician’s breadth of prescribing, we estimate a Poisson regression with the number of different drugs prescribed in a class as the dependent variable (categorized as 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5+ drugs prescribed as initial prescriptions). Estimates from the Poisson regressions are used to predict the number of drugs prescribed by each physician given the characteristics of their patients and formulary designs. We then classify each physician as high, medium or low in narrowness (concentration) of prescribing based on how their actual number of drugs prescribed deviates from the predicted value. We use this classification to assess whether narrow prescribing is associated with three patient-level outcomes: medication adherence, therapeutic switching (changing medications within the class), and out-of-pocket drug costs. We measure each patient’s adherence at the class-level based on the medication possession ratio (MPR) over the six months following the initial prescription. The MPR is expressed as a percentage, defined as the number of days supply of a medication (i.e. possession) over the six months following the initial prescription. Therapeutic switching rates are generally low in the five brand-dominated classes, ranging from 9% for statins to 17% for SSRI/SNRIs. This underscores the importance of the initial drug choice in determining the patient’s course of treatment.

The independent variables include age and its square, gender, and median household income (by 3-digit zip code). We also have salary information (in buckets) for 56 percent of patients. Since two-thirds of those with salary information fall in the “below $50,000” category, we include binary indicators for a high salary (>$50,000) and missing salary information. Since patients receiving prescriptions from specialists are more likely to adhere, we use a proxy for specialist, defined as the share of all of a physician’s observed prescriptions that are in the relevant category, for example, cardiac drugs. We also measure the complexity of formulary designs facing each physician in two ways. First, we count the number of observed health plans represented by the physician’s patients. Second, we compute the number of unique pharmacy benefit designs facing each physician based on the ordering of copayments for the most prescribed brand drug, the second most prescribed brand drug and the top generic drug in the class.

Finally, we control for comorbid conditions related to the drug class using a set of disease indicators identified in the medical claims based on ICD-9 diagnoses. For example, we include binary indicators for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, chronic heart failure, cardiac disease, vascular disease, and stroke for statin users (Full model results are available from the corresponding author). We also include quarterly expenditures on direct-to-consumer and direct-to-physician advertising for each drug, geographic identifiers and some models include plan formulary design and initial drug to control for plan- and drug-specific effects.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the distribution of brand and generic prescribing within each of the ten classes. Most doctors do not prescribe brand or generic medications exclusively, with some notable exceptions. Nearly half of the physicians prescribing ACE inhibitors and NSAIDS and 90 percent of physicians prescribing opiates prescribe only generic drugs in the class. By contrast, less than one percent of physicians prescribe only generic statins or PPIs. As the share of generic prescribing in the class increases, the proportion of physicians prescribing only generics increases and the share prescribing only brands decreases. In the five classes where the generic share is closest to one-half (38 to 61 percent), between 80 and 89 percent of physicians prescribe both brand and generic medications as initial prescriptions.

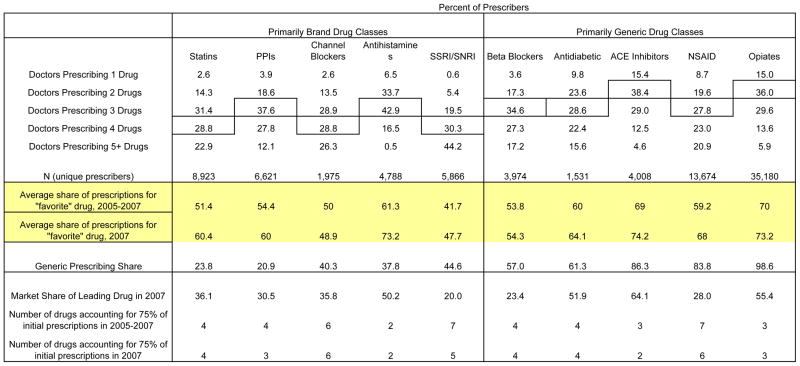

The distribution of the number of drugs prescribed per physician is shown in Table 2. To put these numbers in context, we also report the number of drugs that account for 75 percent of initial prescriptions in the class and the market share of the top-selling drug. Only a small fraction of physicians prescribe a single drug in the class, ranging from less than one percent for SSRI/SNRIs to 15 percent for ACE inhibitors. In eight of the ten classes, the median physician prescribes 3 or 4 different drugs. This reflects broad prescribing given that the median number of initial prescriptions per physician in our sample ranges from 6 to 8 in the 10 classes. The case of SSRI/SNRI antidepressants is particularly striking: 45% of doctors prescribe five or more different drugs in the class. Of the 1,659 doctors for whom we observe 8 to 12 initial prescriptions, 72 percent prescribe five or more different drugs and less than 2 percent prescribe one or two drugs.

Table 2.

Breadth of Physician Prescribing in Brand-dominant and Generic-dominant Classes

|

In each column, the cell containing the median prescriber is boxed.

We define therapeutic classes by the Redbook 2007 classification. Antidiabetic does not include insulin. Antihistamines exclude those used for acute symptoms such as nausea. Antihistamines and NSAIDs exclude products availabe over the counter.

Table 3 shows the distribution of physician prescribing in the five brand-dominated classes. Physicians prescribing one or two drugs are more likely to prescribe the leading drug in the class, which in most cases, is the most heavily promoted drug. For example, among physicians prescribing just 1 statin, 80 percent prescribe the market leader and most heavily promoted drug. The generic share increases with number of initial drugs prescribed in three of the five classes, while PPIs and antihistamines exhibit a different pattern.

Table 3.

Distribution of Physician Prescribing, by Type of Drug and Patient Characteristics

| a. Type of Drug Prescribed | b. Patient Heterogeneity within Doctor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Statins | Generic | Top Drug in Class | Direct to Physician Promotional Expenditures | Number of Plans | Combinations of Chronic Conditions |

| Doctors Prescribing 1 Drug | 2.8 | 79.9 | $159,955 | 3.59 | 4.07 |

| Doctors Prescribing 2 Drugs | 17.2 | 53.6 | $121,118 | 3.53 | 4.26 |

| Doctors Prescribing 3 Drugs | 21.8 | 38.9 | $101,349 | 3.77 | 4.55 |

| Doctors Prescribing 4 Drugs | 25.3 | 30.8 | $88,774 | 4.13 | 5.06 |

| Doctors Prescribing 5+ Drugs | 27.3 | 25.5 | $79,845 | 4.95 | 6.42 |

| Total | 23.8 | 34.5 | $93,882 | 4.10 | 5.07 |

| N | 74,163 | 74,163 | 73,872 | 8,923 | 8,923 |

|

| |||||

| PPIs | Generic | Top Drug in Class | Direct to Physician Promotional Expenditures | Number of Plans | Combinations of Chronic Conditions |

| Doctors Prescribing 1 Drug | 24.1 | 46.3 | $67,463 | 3.36 | 2.60 |

| Doctors Prescribing 2 Drugs | 23.4 | 39.8 | $66,810 | 3.48 | 2.62 |

| Doctors Prescribing 3 Drugs | 22.1 | 34.0 | $65,853 | 3.61 | 2.77 |

| Doctors Prescribing 4 Drugs | 20.3 | 29.6 | $65,222 | 4.12 | 2.95 |

| Doctors Prescribing 5+ Drugs | 17.2 | 27.8 | $64,800 | 5.21 | 3.48 |

| Total | 20.9 | 32.7 | $65,644 | 3.91 | 2.87 |

| N | 52,978 | 52,978 | 52,585 | 6,621 | 6,621 |

|

| |||||

| SS/NRIs | Generic | Top Drug in Class | Direct to Physician Promotional Expenditures | Number of Plans | Combinations of Chronic Conditions |

| Doctors Prescribing 1 Drug | 26.1 | 41.9 | $73,763 | 3.70 | 3.81 |

| Doctors Prescribing 2 Drugs | 36.8 | 37.5 | $63,081 | 3.33 | 3.63 |

| Doctors Prescribing 3 Drugs | 39.6 | 29.0 | $56,487 | 3.46 | 3.76 |

| Doctors Prescribing 4 Drugs | 43.7 | 22.5 | $50,626 | 3.52 | 3.88 |

| Doctors Prescribing 5+ Drugs | 47.0 | 17.1 | $46,189 | 4.18 | 4.97 |

| Total | 44.6 | 21.1 | $49,587 | 3.79 | 4.33 |

| N | 46,040 | 46,040 | 45,092 | 5,866 | 5,866 |

|

| |||||

| Antihistamines | Generic | Top Drug in Class | Direct to Physician Promotional Expenditures- All | Number of Plans | Combinations of Chronic Conditions |

| Doctors Prescribing 1 Drug | 29.8 | 63.5 | $21,458 | 3.61 | 2.40 |

| Doctors Prescribing 2 Drugs | 43.2 | 42.5 | $18,571 | 3.97 | 2.57 |

| Doctors Prescribing 3 Drugs | 37.6 | 37.0 | $22,704 | 4.43 | 2.74 |

| Doctors Prescribing 4 Drugs | 33.5 | 33.1 | $23,999 | 5.53 | 3.15 |

| Doctors Prescribing 5+ Drugs | 30.6 | 25.0 | $19,418 | 5.14 | 3.14 |

| Total | 37.8 | 38.9 | $21,747 | 4.41 | 2.73 |

| N | 39,644 | 39,644 | 39,627 | 4,788 | 4,788 |

|

| |||||

| CCBs | Generic | Top Drug in Class | Direct to Physician Promotional Expenditures- All | Number of Plans | Combinations of Chronic Conditions |

| Doctors Prescribing 1 Drug | 19.8 | 60.1 | $10,122 | 2.96 | 3.90 |

| Doctors Prescribing 2 Drugs | 26.0 | 56.6 | $12,582 | 3.23 | 4.19 |

| Doctors Prescribing 3 Drugs | 35.9 | 41.7 | $11,896 | 3.23 | 4.38 |

| Doctors Prescribing 4 Drugs | 43.0 | 31.8 | $10,705 | 3.27 | 4.60 |

| Doctors Prescribing 5+ Drugs | 48.2 | 25.5 | $9,695 | 3.56 | 5.47 |

| Total | 40.3 | 35.8 | $10,894 | 3.32 | 4.69 |

| N | 13,633 | 13,633 | 13,337 | 1,975 | 1,975 |

In the PPI class, which had only one generic drug (omeprazole) during 2005–2007, the generic share decreases monotonically with the number of drugs prescribed (as does the share of the top brand drug), indicating that narrow prescribers in this class were split between high prescribers of the top (brand) drug and high prescribers of generic omeprazole. Perhaps due to the degree of similarity between these two products (esomeprazole, the top brand and generic omeprazole), doctors generally prescribe one drug or the other. For example, among the 1,229 physicians prescribing just two drugs in the class, only 23 percent prescribed both esomeprazole and omeprazole, while 46.5 percent prescribed the leading brand and another brand drug and 20 percent prescribed generic omeprazole and another brand drug. By contrast, the leading brand and generic antihistamines have different active ingredients and most doctors prescribe both. Overall, as doctors prescribe more broadly, they move away from the most prescribed drug in the class towards generics and/or less common brands.

Physicians treating patients with different comorbidities prescribe more broadly. This pattern occurs in all five classes and is nearly monotonic (Table 3). Further, physicians treating patients from a larger number of health plans (and formularies) are more likely to prescribe broadly. These results are robust to multivariate models that control for detailed patient and plan characteristics (results not shown; see Appendix A)

If broad prescribers are better able to match a patient to their optimal drug, we might observe better adherence to medications and less switching within class. We find that broader prescribing is associated with modestly better adherence in two of the five classes (Table 4). Patients prescribed PPIs and antihistamines by a doctor in the broadest category of prescribing are 7 to 8 percent more likely to continue use for six months than a patient treated by a doctor who prescribes most narrowly. However, we find no statistically significant differences for SS/NRIs and CCBs, and a small opposite effect (lower adherence) for statins. Similarly, we find little evidence to suggest that broader prescribing significantly affects switch rates or the average out-of-pocket cost per 30-day prescription.

Table 4.

Adherence, Out-of-Pocket Costs and Switching Rates, By Physician Prescribing

| a. Predicted MPR within the class within six months of the initial prescription | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Degree of narrow (concentrated) prescribing. | Statins | PPIs | SSRI/SNRI | Antihistamines | Calcium Channel Blockers |

| High | 0.77 | 0.58*** | 0.66 | 0.35*** | 0.77 |

| Medium | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| Low | 0.75* | 0.61 | 0.66 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| Total Average MPR | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.77 |

| N | 60,366 | 42,057 | 36,039 | 32,191 | 10,844 |

| Degree of narrow (concentrated) prescribing. | b. Predicted Annual Copay (Patient Cost of One Year’s Supply) within the class | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Statins | PPIs | SSRI/SNRI | Antihistamines | Calcium Channel | |

| High | $144.03*** | $208.51 | $146.94 | $177.68* | $123.97** |

| Medium | $139.77 | $208.51 | $145.47 | $170.72 | $116.75 |

| Low | $139.77 | $214.86** | $141.17* | $179.467** | $108.85*** |

| Mean Avg Annual Copay | $141.17 | $210.61 | $144.03 | $175.91 | $116.75 |

| N | 41,566 | 26,508 | 31,163 | 18,767 | 8,715 |

| c. Predicted Switching within the class during six months after the initial prescription | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Statins | PPIs | SSRI/SNRI | Antihistamines | Channel Blockers | |

| High | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.19* |

| Medium | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| Low | 0.12*** | 0.18 | 0.22** | 0.14 | 0.20 |

| Total Probability of Switching | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

|

| |||||

| N | 41,621 | 19,930 | 20,436 | 6,585 | 7,594 |

Notes: Dependent variable is calculated as total daily doses purchased within 180 days of initial prescription, divided by 180. Categories of narrowness are tertiles of the percent deviation of each doctor’s number of drugs prescribed from predicted number of drugs prescribed.

Asterisks reflect statistical signifcance at the 1% (***), 5% (**) and 10% (*)

Notes: Dependent variable is calculated as the year-equivalent total copay amount, based on the average copay payment per daily dose in the six months following the initial prescription. To capture plan formulary characteristics, we control for the mean brand copay in the class for each patient’s plan, as well as the mean copay difference between brand and generic drugs. We exclude plans in which these values could not be determined (see Appendix).

Asterisks reflect statistical signifcance at the 1% (***), 5% (**) and 10% (*) level relative to Medium prescribing.

Notes: Dependent variable is binary, equal to 1 if the patient is observed to fill a prescription for another drug in the class, written by the same prescriber as the initial prescription, within six months following the initial prescription. For this analysis, we exclude patients who discontinue therapy in the class within the first six months, and we control for the drug initially prescribed.

Asterisks reflect statistical signifcance at the 1% (***), 5% (**) and 10% (*) level relative to Medium prescribing.

COMMENT

There is a widespread perception that physicians prescribe a narrow range of drugs within a therapeutic class. This is often attributed to two primary factors. The first is clinical experience, wherein physicians gain knowledge of a particular drug through experience and then prescribe it broadly to their other patients. The second factor is pharmaceutical marketing. Prior work has established that detailing has a significant effect on prescribing behavior and brand loyalty, particularly among physicians with limited access to colleagues [2].

Despite these perceptions, we find surprisingly broad prescribing across ten prominent classes. While 40 to 60 percent of their prescriptions are for one drug, the median physician in our sample prescribes at least 3 different drugs for incident users in 8 of the 10 classes. These results are even more striking considering the small number of initial prescriptions per physician (median=8) and the dominance of brand drugs in five of the ten classes studied. Physicians whose patients are covered by a wider array of health plans and formularies prescribe more broadly, as do physicians who treat patients with varying comorbidities. This suggests that attempts to match specific drugs to a patient’s health condition and formulary design are important factors in deviating from the their favorite drug. While physicians who prescribe narrowly are more likely to prescribe highly advertised drugs, few doctors prescribe these drugs exclusively.

Our results suggest that physician prescribing habits are less entrenched than commonly perceived. Why we observe these patterns is unclear. Broad prescribing may simply reflect the increasing number of drugs in a class, many of which act in a similar way and share common side effect profiles. Broad prescribing may also reflect the influence of pharmaceutical marketing, but with less pernicious effects. Surveys of physicians reveal that detailing is an important source of information for many providers, and that drug samples provide greater flexibility in prescribing to low-income patients [20]. The widespread availability and use of drug samples may provide the clinical experience physicians depend on to assess the efficacy and benefits of new products.

An alternative explanation for the observed breadth of prescribing is the influence of manufacturers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and third-party payers. Through explicit campaigns that promote switching to “featured” products or financial incentives inherent in the formulary design, physicians and patients may be steered towards a wider array of products than in the past [21]. These incentives may interact, as prior research suggests that advertising affects demand only for drugs that have preferential status on the patient’s formulary [22].

There are several possible reasons why prescribing of antidepressants, in particular, is so diffuse. First, we categorized SNRIs, NRIs and SSRIs into a single class. More than one-third of doctors in the sample prescribe drugs from all three categories, 61% prescribe both SSRIs and SNRIs and only 17 percent prescribe SSRIs only. This suggests that doctors view these subclasses distinctly and include more than the dominant SSRIs in their prescribing patterns. Further, there are 22 different drugs in the class by product name, but only 8 active ingredients. If we recalculate the number of drugs prescribed based on distinct active ingredients, we find that 32.8% of the doctors (versus 45%) prescribe 5 or more drugs. However, the share of physicians prescribing 1 or 2 drugs rises only from 6% to 8% and the median doctor still prescribes 4 drugs in the class.

Our findings suggest that the vast majority of physicians are not wedded to a “favorite” drug, nor reluctant to try new therapies as more clinical information becomes available or new products enter the market. This is an important finding given the potential social costs of habitual prescribing, where physicians make prescription decisions based on incomplete information [23]. Nonetheless, the use of a few drugs may be associated with high quality prescribing in some therapeutic classes [5]; [14].

Our analysis has several limitations. First, pharmacy claims do not solely reflect the choice of physicians, but also the preferences of patients and the input of the pharmacist and health plan. The actual prescribing patterns of physicians is likely to be narrower than observed in our analysis if patient preferences and formulary incentives lead to therapeutic substitutions at the pharmacy. While recent evidence suggests that patients have an impact on prescribing decisions, physician preferences dominate [24]; [25]. Second, we only observe a subset of each physician’s patients, specifically those enrolled in the set of employer-sponsored plans covered by our dataset. Thus, we may understate how many different drugs each doctor prescribes to incident users. Third, we examine physician prescribing over a three-year period to increase the number of physicians and initial prescriptions in our sample. However, additional drugs may enter the market and new clinical information may emerge over this period that would cause physicians to change their choice of drugs. Analyzing prescribing patterns over a one-year period reduces the average number of drugs prescribed in a class, but the median physician still prescribes 3 drugs or more in 7 of the ten classes. Fourth, we lack detailed demographic information on physicians. However, we estimate their degree of specialization by measuring the fraction of a physician’s observed prescriptions in the relevant therapeutic category. Finally, some of the patients classified as incident users in our sample already had experience with a drug in the class beyond our 1-year “clean window”, which may inform the doctor’s current choice of medication. To test the extent of this error, we examined patients with a two-year clean window prior to their “initial” prescription. Although this reduced our sample size by more than half, it did not substantively change our results.

While we observe broad prescribing in one dimension, we cannot separate the independent effects of the physician from that of the patient and the formulary. The use of electronic prescribing will allow future studies to examine differences in what is prescribed by the physician and what is dispensed at the pharmacy. More detailed data is needed to understand how prescribing practices vary by physician age, gender, specialty, and practice setting. For instance, prescribing patterns may be quite different in fully integrated health systems or in plans with pharmacists embedded in clinical teams. Future work also should explore the appropriateness and clinical effects of broad versus narrow prescribing, which is likely to vary across therapeutic classes. We find that broader prescribing has small and inconsistent effects on several patient-level outcomes, but more work in this area is needed.

TAKE-AWAY POINTS.

Physicians prescribe more broadly than commonly perceived. Although most physicians have a “favorite” drug, they are not reluctant to try new therapies. Physicians who prescribe broadly see more patients with varied comorbidities and formulary designs. Prescribing fewer drugs is associated with lower rates of medication adherence and higher out-of-pocket costs, but the effects are small and inconsistent across classes.

Broad prescribing may be due to the:

increasing number of drugs in a class,

pharmaceutical marketing, particularly direct-to-physician promotions

the role of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and third-party payers

Acknowledgments

The authors research in this area was sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), 1R01AG029514 - 01A2. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Appendix A.

Poisson regressions of narrowness of prescribing on characteristics of doctors and patients

| (1) Statin | (2) PPI | (3) SS/NRI | (4) Antihistamines | (5) Calcium Channel Blockers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y = Number of drugs prescribed as initial prescriptions | |||||

| Combinations of chronic conditions | 0.144*** (0.0197) | 0.179*** (0.0543) | 0.274*** (0.0383) | 0.0317 (0.0471) | 0.172* (0.0705) |

| Combinations of chronic conditions | −0.00691*** (0.00134) | −0.0191* (0.00799) | −0.0225*** (0.00340) | 0.00174 (0.00679) | −0.0114 (0.00596) |

| Different copay orderings | −0.0106 (0.0170) | 0.0442* (0.0172) | 0.0776*** (0.0217) | 0.123*** (0.0171) | 0.0901* (0.0399) |

| Number of plans | 0.108*** (0.0177) | 0.0707*** (0.0168) | 0.0814** (0.0295) | 0.00421 (0.0138) | 0.118 (0.0768) |

| Number of plans (squared) | −0.00670*** (0.00136) | −0.00315** (0.00109) | −0.00808** (0.00252) | 0.0000271 (0.000762) | −0.0198* (0.00907) |

| Initial prescriptions observed | 0.122*** (0.00969) | 0.119*** (0.0148) | 0.265*** (0.0216) | 0.0231** (0.00716) | 0.427*** (0.0405) |

| Initial prescriptions (squared) | −0.00167*** (0.000221) | −0.00168*** (0.000411) | −0.00226*** (0.000476) | −0.000399** (0.000140) | −0.0105*** (0.00148) |

| Patients with prior use in class | 0.0936*** (0.0138) | 0.0917*** (0.0177) | 0.131*** (0.0216) | 0.0822*** (0.0128) | 0.0134 (0.0431) |

| Patients with prior use (squared) | −0.00166 (0.00145) | −0.00701** (0.00234) | −0.00914** (0.00281) | −0.00216 (0.00117) | 0.00681 (0.00674) |

| Half years with a prescription | 0.159*** (0.0152) | 0.0793*** (0.0166) | 0.155*** (0.0244) | 0.137*** (0.0148) | 0.102** (0.0346) |

| Observations | 8923 | 6621 | 5866 | 4788 | 1975 |

| ll | −15357.9 | −10940.8 | −10619.1 | −7370.9 | −3474.9 |

| ll_0 | −15906.1 | −11174.1 | −11293.6 | −7465.4 | −3589.9 |

Footnotes

None of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Gagnon MA, Lexchin J. The cost of pushing pills: a new estimate of pharmaceutical promotion expenditures in the United States. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manchanda P, Honka E. The effects and role of direct-to-physician marketing in the pharmaceutical industry: an integrative review. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2005;5(2):785–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hensley S, Martinez B. To sell their drugs, companies increasingly rely on doctors. In: East, editor. Wall St J. 2005. p. A1.p. A2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berkeley JS, I, Richardson M. Drug usage in general practice. An analysis of the drugs prescribed by a sample of the doctors participating in the 1969–70 North-east Scotland workload study. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1973;23(128):155–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinburapa V, et al. Physician prescribing decisions: the effects of situational involvement and task complexity on information acquisition and decision making. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(11):1473–82. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90389-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britten N, et al. Continued prescribing of inappropriate drugs in general practice. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20(4):199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1995.tb00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGavock H, Wilson-Davis K, Connolly JP. Repeat prescribing management--a cause for concern? Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(442):343–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buusman A, Kragstrup J, Andersen M. General practitioners choose within a narrow range of drugs when initiating new treatments: a cohort study of cardiovascular drug formularies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(9):651–6. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0973-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taub LM, et al. The Diversity of Concentrated Prescribing Behavior: An Application to Antipsychotics. NBER. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank RG, Zeckhauser RJ. Custom-made versus ready-to-wear treatments: behavioral propensities in physicians’ choices. J Health Econ. 2007;26(6):1101–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce GF, et al. Employer drug benefit plans and spending on prescription drugs. Jama. 2002;288(14):1733–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huskamp HA, et al. The effect of incentive-based formularies on prescription-drug utilization and spending. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(23):2224–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa030954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman DP, et al. Pharmacy benefits and the use of drugs by the chronically ill. JAMA. 2004;291(19):2344–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiff GD, Galanter WL. Promoting more conservative prescribing. JAMA. 2009;301(8):865–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasser KE, et al. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2215–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kravitz RL, et al. Influence of patients’ requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(16):1995–2002. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.16.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman JS, et al. Consumers’ reports on the health effects of direct-to-consumer drug advertising. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W3–82–95. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mintzes B, et al. Influence of direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising and patients’ requests on prescribing decisions: two site cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2002;324(7332):278–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7332.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strunk BC, Reschovsky JD. Kinder and gentler: physicians and managed care, 1997–2001. Tracking report [electronic resource]/Center for Studying Health System Change. 2002;(5):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew LD, et al. A physician survey of the effect of drug sample availability on physicians’ behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(7):478–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler DA, et al. Therapeutic-class wars--drug promotion in a competitive marketplace. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(20):1350–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411173312007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wosinska M. Just What the Patient Ordered? Direct-to-Consumer Advertising and the Demand for Pharmaceutical Products. SSRN eLibrary; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellerstein JK. The importance of the physician in the generic versus trade-name prescription decision. Rand J Econ. 1998;29(1):108–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kravitz RL, Chang S. Promise and perils for patients and physicians. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(26):2735–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneeweiss S, et al. A Medicare database review found that physician preferences increasingly outweighed patient characteristics as determinants of first-time prescriptions for COX-2 inhibitors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(1):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]