Abstract

Beta-barrel membrane proteins have regular structures with extensive hydrogen bonding networks between their transmembrane (TM) β-strands, which stabilize their protein fold. Nevertheless, weakly stable TM regions exist, which are important for the protein function and interaction with other proteins. Here, we report on the apparent stability of human Tom40A, a member of the ‘mitochondrial porin family’ and main constituent of the mitochondrial protein-conducting channel TOM. Using a physical interaction model TmSIP for β-barrel membrane proteins, we have identified three β-strands unfavorable in the TM domain of the protein. Substitution of key residues inside these strands with hydrophobic amino acids results in a decreased sensitivity of the protein to chemical and/or thermal denaturation. The apparent melting temperature observed when denatured at a rate of one degree per minute, is shifted from 73 to 84 °C. Moreover, the sensitivity of the protein to denaturant agents is significantly lowered. Further, we find a reduced tendency for the mutated protein to form dimers. We propose that the identified weakly stable β-strands 1, 2 and 9 of human Tom40A play an important role in quaternary protein-protein interactions within the mammalian TOM machinery. Our results show that the use of empirical energy functions to model the apparent stability of β-barrel membrane proteins may be a useful tool in the field of nanopore bioengineering.

Keywords: Eukaryotic porins, bacterial porins, human Tom40, TOM complex, oligomerization states, weakly stable transmembrane β-strands

INTRODUCTION

The transmembrane (TM) domains of β-barrel membrane proteins have regular structures with an extensive hydrogen bonding network between the individual β-strands 1,2. Despite this strong network, unfavorable or weakly stable regions exist in several β-barrel membrane proteins 3; 4. They are often important for their function, such as voltage sensing 5, flux control of metabolites and ion-sensing (see 6,7 for a detailed review).

In general, β-barrel membrane proteins are stabilized through binding of α-helices to weakly stable regions inside or outside of the pore, so-called in-plugs or out-clamps, through formation of oligomers via protein-protein interfaces, or interactions with lipids 3; 4; 6; 8.

In this work, we explore whether the prediction of weakly stable regions in bacterial β-barrels 3; 4 can be adapted to human Tom40A (hTom40A) and reveal further insights on the structural organization of this protein.

In eukaryotes, Tom40 proteins represent an essential class of pore proteins, which facilitate the translocation of unfolded proteins from the cytosol into mitochondria. They comprise the main subunit of the TOM import machinery in mitochondrial outer membranes 9; 10; 11; 12; 13; 14.

It is generally predicted that all eukaryotic Tom40 proteins belong to the ‘mitochondrial porin’ superfamily. Thus, hTom40A most likely constitutes a β-barrel architecture similar to VDAC-1 with 19 β-strands and a short α-helix located inside the pore 15; 16; 17. Consistent with this model, circular dichroism and Fourier transform infrared secondary structure analyses of Tom40 and VDAC proteins from different organisms revealed a dominant β-sheet structure with a small α-helical part 9; 18; 19.

In the present study, we calculated the energy of each amino acid in the predicted native conformation of hTom40A using a recently introduced empirical potential function, which was developed based on extensive combinatorial analysis of known bacterial β-barrel membrane protein structures 3. We have identified three β-strands, 1, 2 and 9, in the TM domain of hTom40A that contribute to the overall sensitivity of the protein to denaturation. We show that mutagenesis of the predicted specific destabilizing amino acid residues within these strands leads to a higher resistance to thermal or chemical perturbation of the barrel. Similar results were obtained with Tom40 from Aspergillus fumigatus (AfTom40). We propose that the unstable β-strands 1, 2 and 9 of the TM domain of hTom40A interact with other Tom40 molecules or subunits of the TOM complex.

RESULTS

Weakly stable regions in hTom40A and oligomerization index

The stability of β-barrel membrane proteins is determined by the balance between favourable hydrogen bonding, van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions as well as unfavourable conformational entropy. To identify weakly stable regions in the TM domain of wild-type hTom40A (Fig. 1A and B), we estimated the energetic contribution of all amino acid residues to the β-strand stability of the protein by using a computational approach 3 that has recently been applied to model the conformational stability of 25 non-homologous β-barrel membrane proteins of known structure. Briefly, we calculated energetics of embedding specific residue types at different regions of the TM domain, the stabilizing effect due to interactions between residues on neighbouring strands through strong H-bond, weak H-bond, and side-chain side-chain interactions using the updated TmSIP empirical energy parameters 3; 20.

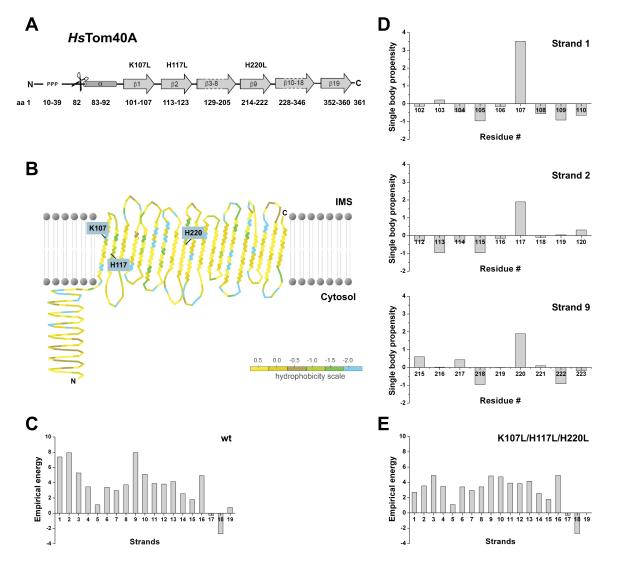

Fig. 1.

Expected energy levels of strands and residues in the transmembrane domain of hTom40A. (A) Secondary structure prediction of hTom40A is based on PRED-TMBB 34 and TMBETAPRED-RBF 35. (B) Protein topology of hTom40A was generated using TMRPres2D 51. (C) Empirical energy of β-strands 1 - 19 of wild-type protein. β-strands 1, 2 and 9 are predicted as the weakly stable strands. (D) Single body propensities of amino acid residues of the transmembrane domains of β-strands 1, 2 and 9. Amino acids K107, H117, and H220 show the highest values indicating a destabilizing effect on the regarding strand. (E) Empirical energy of β-strands 1 - 19 of mutant (K107L, H117L and H220L) human Tom40A.

We calculated the contribution of residues to the empirical energy for each β-strand (Fig. 1C). Strands 1, 2 and 9 have significantly higher empirical energies and are thus less favorable than the rest of the protein. Then, the oligomerization index ϱwt, which summarizes the energy deviation of unstable strands from the expected energy value for all the strands in the protein, was calculated to be ϱwt = 2.48. This is based on the observation that highly unfavourable strands are often associated with protein-protein interfaces in the TM region.

In data sets using sequence information of bacterial β-barrel membrane proteins, a protein can be predicted to be monomeric if the oligomerization index is < 2.25 and oligomeric if it is > 2.75 3. The oligomerization index of hTom40A is between these prediction thresholds. Theoretically, wild-type hTom40A may thus exist as stable monomers but may also form higher order complexes through distinct protein-protein interaction interfaces.

We further examined the contribution of all amino acids facing the membrane lipids within the predicted three unfavorable strands 1, 2 and 9 (Fig. 1D). In this analysis, residues K107 in strand 1, H117 in strand 2, and H220 in strand 9 were found to contribute the most to the instability of these strands. Based on our calculations, we predict strands 1, 2 and 9 of hTom40A to be unfavorable / weakly stable. Each strand can have two orientations; the side-chain of the first residue can either face the lipid environment or the internal of the barrel. The orientations of strands are predicted using the energy scale in reference 3 such that the number of costly burial of ionizeable/polar residues facing the lipid environment is overall minimized.

Secondary and tertiary structure of hTom40A

In order to account for the differences between bacterial and mitochondrial β-barrel membrane proteins, and keeping in mind that hTom40A forms complexes also with other components of the TOM machinery, we wanted to construct a mutant protein to have an oligomerization index ϱ below 1.5 so that the resulting mutant hTom40A would form more stable monomers, possibly without protein-protein interaction interfaces.

To test to what extent β-strands 1, 2, and 9 determine the overall resistance to denaturation and oligomerization state of hTom40A, we designed five mutants, termed K107L, H117L, H220L, K107L/H117L and K107L/H117L/H220L, where residues K107, H117 and H220 of hTom40A are replaced by leucines. Leucine is predicted to be the most stabilizing amino acid when facing the lipid within the core region of a transmembrane β-strand 3.

The empirical energy profile of the triple mutant hTom40Amut (K107L/H117L/H220L) is shown in Fig. 1E. The oligomerization index of this mutant (ϱK107L/H117L/H220L=1.37) was significantly lower than that of the wild-type protein (ϱwt = 2.48), predicting a very robust monomeric β-barrel membrane protein. Energy calculations of single and double mutants revealed higher indices (ϱK107L=2.08, ϱH117L=2.01, ϱH220L=2.03, ϱK107L/H117L=1.91, ϱK107L/H220L=1.71, ϱH117L/H220L=1.68) predicting less stable proteins.

Mammalian Tom40A isoforms show a very high sequence identity amongst each other (>91 %, data not shown). All include a remarkable N-terminal poly-proline region, which is only present in mammalian Tom40A. So far, thermal stability analyses of the TM β-barrels of mammalian full length Tom40A proteins using UV-CD spectroscopy have not been successful in our hands (data not shown). The β-barrel UV-CD signals appeared to be superimposed by strong CD signals caused by the poly-proline rich region of the protein. As a consequence of this interference, temperature-induced transitions of the β-barrel itself could not be monitored accurately. Since the N-terminal poly-proline rich domain in mammalian Tom40A proteins has no effect on the channel formation 21, we deleted the poly-proline region of all hTom40A proteins to improve the CD-signal in heat-induced unfolding measurements.

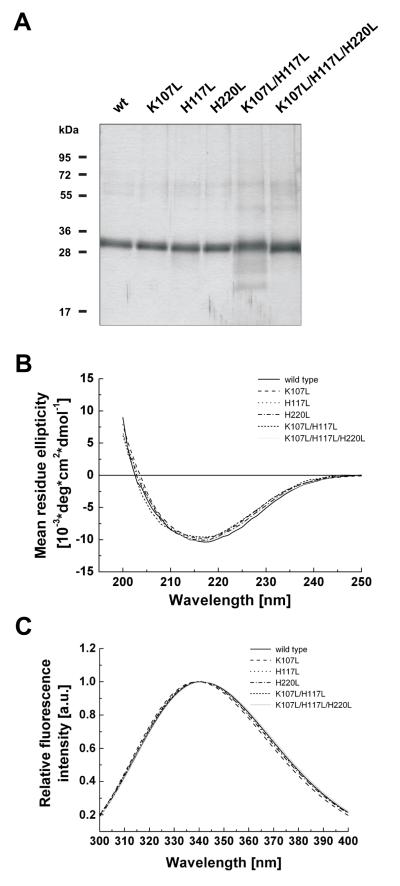

Wild-type and mutant Tom40A proteins were expressed in E. coli and Nickel-affinity purified from inclusion bodies under denaturing conditions. The proteins were refolded by rapid dilution of denaturant into LDAO-containing detergent buffer and further purified via size exclusion chromatography. Analysis of refolded proteins by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie and silver staining (Fig. 2A) indicated that all isoforms were virtually pure. UV-CD spectroscopy showed typical beta barrel spectra for wild-type and mutant proteins with similar curves for all hTom40A isoforms 9; 10; 18; 21 (Fig.2B). The spectral characteristics of the wild-type hTom40A and the triple mutant are summarized in supplementary Table 2. At wavelengths >250 nm, the CD spectra approached ellipticity values close to zero, indicating that the protein preparations were virtually free of higher order aggregates, which would cause light-scattering effects and interfere with the interpretation of the data.

Fig. 2.

Far-UV CD spectra and tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of wild-type and mutant hTom40A. (A) SDS-PAGE showing purified wild-type (wt) and mutant (K107L; H117L; H220L; K107L/H117L; K107L/H117L/H220L) human Tom40A. Proteins were visualized by silver staining. (B) Comparison of far-UV CD spectra between wild-type and mutant hTom40A. Measurements were carried out at a protein concentration of ~0.2 mg/ml at 25 °C for wild-type and mutant proteins, respectively. For each experiment, five scans were accumulated at the indicated temperatures. Noisy data below 200 nm due to optical density has been removed. (C) Comparison of tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of wild-type and mutant hTom40A. Emission spectra were conducted in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1 % (w/v) LDAO, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 350 mM guanidinium hydrochloride at a protein concentration of ~0.15 mg/ml for all isoforms. Data points were fitted to the log-normal distribution as described in materials and methods. Relative fluorescence intensity is in arbitrary units (a.u.). All isoforms exhibit the exact same far UV-CD and tryptophane fluorescence emission spectra characteristics. We suggest analogue β-barrel formation for wild type and mutant hTom40A.

Further, tertiary structure was analyzed via tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy. The emission spectra of wild-type and all mutant Tom40 proteins (Fig. 2C) were exactly the same, with intensity maxima at approximately 340 nm and an unchanged width of the emission spectra. This can be interpreted as an unaltered environment of the widely spread tryptophan residues, W188, W259 and W322, which are conserved in the amino acid sequence of all isoforms and remain unchanged in all our designed mutant proteins. In summary, we suggest that secondary and tertiary structures match in all hTom40A isoforms and consequently differences in resistance to chemical and thermal perturbation and oligomerization state are not due to an altered protein structure.

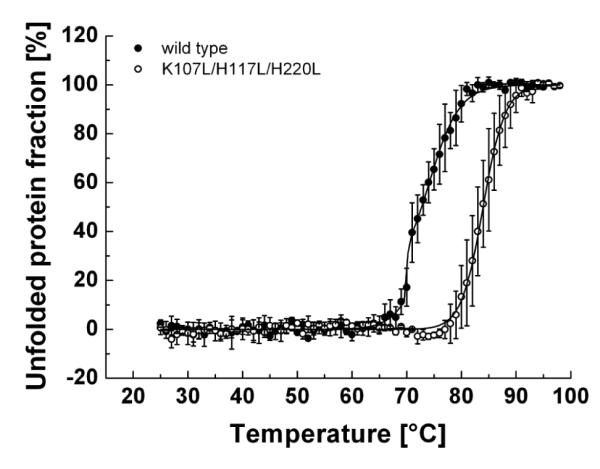

Thermal and solvent stability of hTom40A

To compare the thermal stability of wild-type and mutant hTom40A, CD signals were measured at different temperatures at constant wavelength. Wild-type hTom40A unfolded at an apparent melting temperature of about 73 °C, when denatured at a rate of 1°C per minute (Fig. 3). In line with our energy calculations described above, hTom40A with substitutions at positions K107, H117 and H220 revealed an apparent midpoint of resistance to thermal denaturation of approximately 84 °C (Fig. 3). The single and double mutants did not appear to be significantly more stable than wild-type protein, however differences proved not to be significant (data not shown).

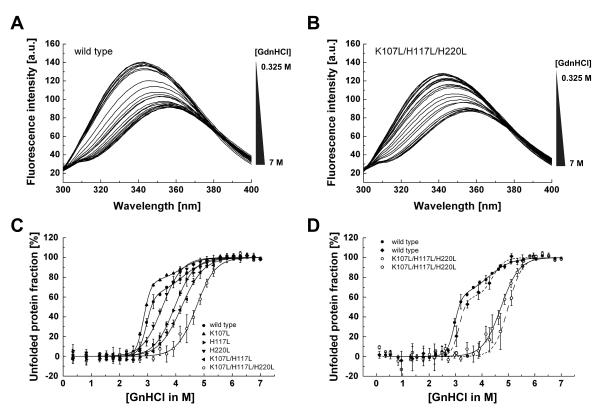

Fig. 3.

Sensitivity of wild-type and mutant hTom40A to thermal denaturation. Thermal denaturation of both hTom40A isoforms was monitored under the same conditions as described in figure 2B by change of ellipticity at 216 nm. Wild-type and mutant protein were subjected to temperature increases of 1 °C/min from 25 to 98 °C, respectively. Data points of melting curves were normalized to the minimum and maximum percentage of unfolded protein fraction (n = 3) 52 and then fitted to sigmoid functions (black line). Apparent melting temperatures were retrieved at the midpoint of the transition curves. Wild-type Tom40A indicated a three-state unfolding mechanism, whereas the triple mutant hTom40A showed a two-state unfolding mechanism with an approximately 11 °C higher apparent melting temperature.

To provide further evidence that substitution of unfavorable amino acids in the TM domain of hTom40A results in conformational stabilization of the protein, we compared tryptophan fluorescence spectra of wild-type and mutated hTom40A in the presence of chemical denaturants. The change in tryptophan fluorescence of wild-type and mutated hTom40A, respectively, was monitored at different Guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl) concentrations, (Figs. 4A and B). Wild-type Tom40 was completely denatured in ~4.5 M GnHCl. The apparent midpoint of unfolding occurred at a concentration of ~3.1 M GnHCl. On the other hand, the resistance of mutant Tom40 K107L/H117L/H220L to chemical denaturation was greatly enhanced (Fig. 4C). The apparent midpoint of unfolding of hTom40A was shifted from 3.1 to approximately 4.8 M GnHCl. Mutant hTom40A K107L/H117L/H220L completely unfolded at ~6.3 M GnHCl. These results were obtained no matter whether unfolded or refolded Tom40 was incubated with GnHCl (Figs. 4C and D), showing the reversibility of the chemical denaturation.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity of wild-type and mutant hTom40A to chemical denaturation. (A and B) Tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra of wild-type and mutant hTom40A ~0.15 mg/ml were recorded in Tris-HCl buffer containing 1 % LDAO after 24 h incubation with guanidinium hydrochloride (GnHCl) at 25 °C. GnHCl concentrations varied from 0.35 to 7 M, respectively. (C) The fractions of unfolded wild-type and mutant Tom40 were determined at different GnHCl concentrations from fluorescence intensities recorded at 330 nm. (C and D) The fractions of unfolded wild-type and mutant Tom40 were determined at different GnHCl concentrations from fluorescence intensities recorded at 330 nm relative to a denaturated (C) and a renaturated (D) protein solution. To allow direct comparison of the reversibility of the unfoldiug reaction, the fractions of unfolded wild-type and K107L/H117L/H220L hTom40A shown in panel (C) are included also in (D) and fitted with solid lines. The figures show an average (sem ± sd) of three independent experiments.

Chemical unfolding of hTom40A K107L, H220L, H117L and K107L/H117L occurred at around 2.9, 3.5, 3.9 and 4.2 M GnHCl (Fig. 4C). These mutants were thus more resistant to chemical denaturation than wild-type hTom40A but less resistant than the triple mutant K107L/H117L/H220L. Our data indicate that the resistance of the mutants to chemical denaturation increased with decreasing ϱ-values. They furthermore suggest that wild-type hTom40A unfolds via a multi-state mechanism whereas unfolding of “stabilized” protein follows a two-state conformational transition.

Thermal and solvent stability of AfTom40

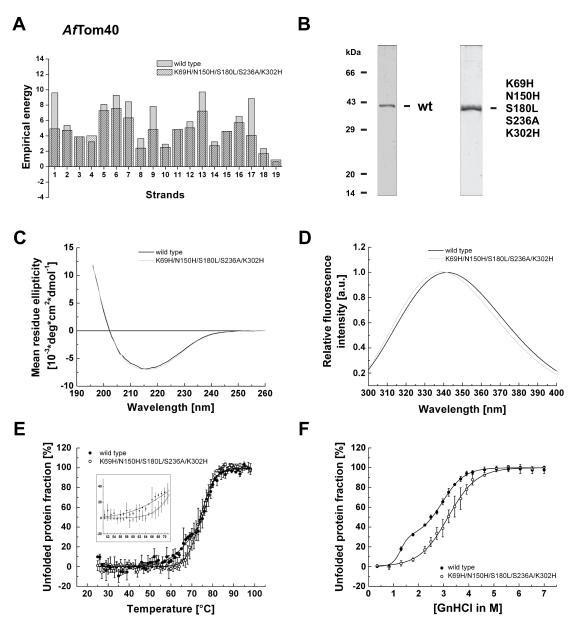

To further test the prediction of weakly stable β-strands in eukaryotic porins, we applied stability calculations to full length Tom40 from Aspergillus fumigatus (AfTom40). Comparison of full length AfTom40 and wild type hTom40AΔ1-82 revealed a moderate identity at the amino acid level (~25% identical residues in the conserved TM part, including the N-terminal helix), but a similar β-barrel secondary structure (supplementary Fig. 1). We identified five unstable regions in AfTom40 to compromise the stability of β-strands 1, 5-7, 9, 13 and 17 (Fig. 5A). The ϱ-value of the wild-type protein was calculated to be 2.81. To see to what extent these β-strands determine the stability of the protein, an AfTom40 variant was made with mutations K69H, N150H, S180L, S236A and K302H. These mutated residues were predicted to be the most favorable residues in the respective positions of the β-strand by the TmSIP potential function. The ϱ-index of this mutant was calculated as 1.66 (Fig. 5A). Wild-type and mutant AfTom40 were over-expressed in E. coli cells, purified under denaturing conditions and refolded into polyoxyethylene monolauryl ether (Brij35) detergent containing buffer in a similar way as hTom40A (Fig. 5B). Far UV-CD spectra of both proteins (Fig. 5C) showed a β-barrel fold as for hTom40A. Tryptophane fluorescence emission spectra were also almost identical supporting a similar structure for both AfTom40 proteins (Fig. 5D). Thermal denaturation of both AfTom40 proteins followed by CD-spectroscopy revealed no difference in the apparent melting temperature but a clear change in the cooperativity in unfolding (Fig, 5E). In contrast to thermally induced unfolding, chemically induced unfolding of wild-type and mutant AfTom40 proteins revealed an apparent stabilization of the mutant protein (Fig. 5F). The apparent midpoint of unfolding of wild-type protein was observed around 2.5 M and was shifted to about 3.2 M GnHCl in the mutant protein. Both patterns of unfolding were in line with those observed for thermal unfolding (Fig, 5E) and those observed for hTom40A (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 5.

Stability analysis of Tom40 from Aspregillus fumigatus. (A) Empirical energy of β-strands 1 - 19 of wild-type and mutant protein. (B) SDS-PAGE of purified and refolded wild-type (wt) and mutant (K69H, N150H, S180L, S236A and K302H) AfTom40 throughout Coomassie blue staining. Far-UV CD spectra (C) and tryptophan fluorescence emission spectra (D) of AfTom40wt/mutant were recorded and deconvoluted as described in Fig.2, respectively. Both AfTom40 isoforms adapt the same secondary structure (C), but mutant AfTom40 showed an approx. 1.5 nm left-shifted tryptophan fluorescence emission spectrum. Thermal (E) and chemical (F) sensitivity of AfTom40 isoforms was investigated according to Fig. 3 and 4C. Thermal and GnHCl induced unfolding of proteins revealed a three-state unfolding mechanism for the wild-type and a two-state unfolding mechanism for the mutant protein with a higher stability for the mutated form of AfTom40.

Oligomerization states of hTom40A

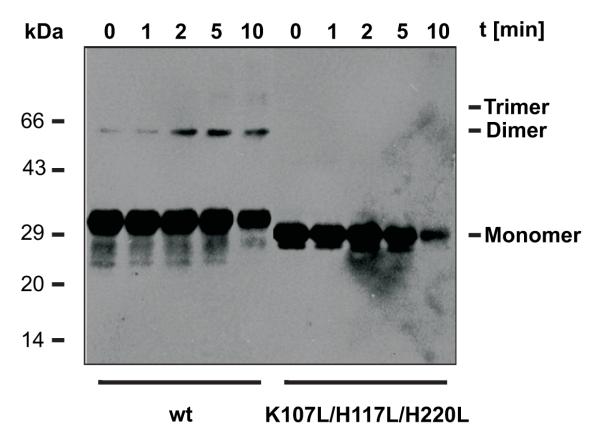

Previous studies revealed that weakly unfavorable regions in bacterial β-barrel proteins can be stabilized through oligomerization of monomers 3. Our energy calculations described above predicted a very stable monomeric form for the mutant hTom40A K107L/H117L/H220L. To verify this hypothesis, we conducted chemical cross-linking experiments on both wild-type and triple-mutant Tom40 solubilized in LDAO. Both protein samples were incubated with glutaraldehyde, which forms covalent bonds between primary amine groups. The degree of intermolecular cross-link formation was evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (Fig. 6). Wild-type hTom40A was present mostly in its monomeric form, but also formed dimers. In contrast, mutant protein was predominantly monomeric and revealed virtually no dimers. Similar results were obtained with proteins in β-dodecylmaltoside-containing buffer (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Chemical cross-linking of wild-type and mutant (K107L, H117L and H220L) hTom40A. Wild-type and mutant protein (40 μM) were incubated with glutaraldehyde (125 μM) at 37 °C in 20 mM NaH2PO4; pH 8. Aliquots were taken after the addition of the cross-linking reagent at the time indicated. In these, cross-linking reactions were stopped by addition of 50 mM Tris, pH 8. Proteins and cross-linking products were visualized by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

It should be noted, however, that long exposures of both proteins to glutaraldehyde resulted in protein aggregates which did not enter the SDS gel. In summary, we conclude successful stabilization of the hTom40A β-barrel. Hence, for mutant hTom40A K107L/H117L/H220L oligomerization is not required to compensate for unfavorable regions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we applied a recently developed method for the prediction of unfavorable regions in bacterial β-barrel membrane proteins 3 to eukaryotic hTom40A. We identified and experimentally confirmed two regions in the TM domain of the protein (β-strands 1 and 2, and β-strand 9), which have strong impact on its resistance to thermal and chemical perturbation. Oligomerization of hTom40A monomers might provide the mechanism to counterbalance the overall β-barrel instability, indicating possible protein-protein interfaces in mammalian Tom40 proteins. Indeed, existence of dimeric and trimeric Tom40 forms was shown for fungal Tom40 27; 28. However, for mammalian Tom40 proteins experimental evidence has yet to be shown. Nevertheless, our results suggest that β-strands 1, 2 and 9 in the TM domain of mammalian Tom40 might be important for the association of single Tom40 molecules. In addition, other subunits of the mitochondrial protein import machinery TOM, e.g. the small Tom proteins, might also interact with β-strands 1, 2 and 9 in the TOM complex from mammals 29.

Interestingly, the key amino acids K107, H117 and H220 in the two unfavourable regions of hTom40A are not strongly conserved between different species (e.g. fungi and plants). This and the results of our stability calculations for AfTom40 indicate that weakly stable regions in mammalian Tom40 proteins differ from evolutionarily more distant Tom40 β-barrels.

Using the above described method for the prediction of unfavourable regions on fungal Tom40 from Aspergillus fumigatus, we identified five unstable domains comprising strands 1, 5-7, 9, 13 and 17. As in the case of mammalian TOM complex, these five unstable domains in fungal Tom40 proteins might play an important role for the interaction with other subunits of the TOM complex in fungi 33. It is tempting to suggest that the assembly and dissociation of the TOM complex is caused by the compensation of weakly stable regions in the TM domain of Tom40 by the association of other TOM subunits and Tom40 itself, not only in detergent buffer but also in the in vivo membrane environment of mitochondria.

Empirical energy calculations on AfTom40 predicted a significantly more favourable interactions of the protein upon mutations in β-strands 1, 7, 9, 13 and 17. However, experimental analysis revealed only a moderate resistance of the protein to chemical and thermal denaturation. A possible explanation for this could be that the full length AfTom40 construct used in this study comprises not only a β-barrel domain, but has additional large N- and C-terminal random coil and α-helical tails. They unfold at low temperatures and low GnHCl concentrations compromising the CD- and fluorescence signals of β-barrel unfolding and complicate the empirical energy calculations of the β-barrel. Another reason could be the imprecise nature of the identified locations of the 19 β-strands of AfTom40, which is used for the empirical energy calculations.

We conclude that computational prediction of unfavourable regions in β-barrel membrane proteins displays a useful tool to improve the resistance of eukaryotic β-barrel proteins to thermal and chemical denaturation. With bioinformatics-derived empirical energy parameters and calculation of thermodynamic properties based on a firm statistical mechanical model, we can now begin to combine both experimental and computational approaches to engineer β-barrel membrane proteins with rationally designed biophysical properties. We propose that our method can be easily adapted to the stabilization of other β-barrel membrane proteins, which is of high interest in e.g. nanotechnology 30 and structural biology 31; 32.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Secondary structure and weakly stable amino acid residues prediction

The software packages PRED-TMBB 34 and TMBETAPRED-RBF 35 were used for the prediction of the secondary structure of hTom40A and AfTom40. Sequence conservation and UV-CD spectra data were incorporated in the secondary structure prediction. The oligomerization index ϱ 3 for the presumably 19-stranded β-barrel indicated the presence of higher-order protein complexes. We examined the predicted lipid facing residues and those with relatively higher energy values are predicted to be weakly stable. The calculation of energy values of individual β-strand residues were performed as described in reference 3. Briefly, we calculated the energy of each residue in the predicted native conformation using an empirical potential function TmSIP derived from bioinformatics analysis of β-barrel membrane proteins 36, first developed in 20; 37; 38, and further refined with additional structural data in 3; 4. The energy for each residue consists of two terms. First, each residue is assigned an energy value of burying this residue type at a particular depth in the lipid bilayer and with the orientation of its side-chain. There are two possible orientations, namely, side-chains facing the lipid environment or facing inside the barrel. This is termed the “single body term”. Second, each residue interacts with two residues on separate neighboring strands through strong backbone H-bond interaction, side-chain interactions and weak H-bond interactions, which collectively make up the two-body energy term. Strand energy is the summation of both single body and two-body energy terms over all residues in the strand.

Cloning and strains

For recombinant expression of wild-type hTom40A in E. coli, a truncated version of the protein lacking amino acid residues 1 to 82 was used (Fig. 1A). The corresponding gene (hTom40AΔ1-82) was PCR-amplified and cloned into a pET24d vector (Novagen) introducing a C-terminal His6-tag into the protein for purification {Mager, 2011 #1146}. The triple mutant hTom40AΔ1-82mut (K107L, H117L and H220L) was prepared by site-directed mutagenesis using hTom40AΔ1-82 as a template and Pfu Ultra II DNA Polymerase (Agilent Technologies Inc.). First, replacement of amino acids K107L, H117L was accomplished by using primers for-K107L-H117L and rev-K107L-H117L (Table 1). Second, to generate the mutation H220L the plasmid containing mutations K107L and H117L was further mutagenized with primers for-H220L and rev-H220L (supplementary Table 1). Single hTom40A mutants K107L and H117L were made by site directed mutagenesis of hTom40AΔ1-82 by using the primers for-H117L/rev-H117L and for-K107L/rev-K107L, respectively (Table 1). In all cases, methylated parental plasmids were specifically digested with DpnI (New England Biolabs). Final plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Eventually, all vectors were transformed into E.coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3) (Stratagene, Agilent Technolgies) cells for protein expression.

The protein sequence of Tom40 from Aspergillus fumigatus was retrieved from the Aspergillus Genome Database. The corresponding gene and an AfTom40 gene coding for a protein with mutations K69H, N150H, S180L, S236A and K302H were synthesized and cloned into a pET24d vector (GeneArt / Invitrogen). Both genes encoded for proteins with a carboxy-terminal hexahistidine tag. To produce these AfTom40 proteins, vectors containing wild-type and mutant AfTom40 were transformed into E.coli C41(DE3) (Lucigen) and BL21(DE3) (Stratagene, Agilent Technolgies) cells, respectively.

Protein expression and isolation of inclusion bodies

Wild-type human Tom40A (hTom40AΔ1-82) and mutated human Tom40A (hTom40AΔ1-82mut) were expressed forming inclusion bodies in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3) under tight control of expression from the T7 promoter. To obtain wild-type protein, BL21-CodonPlus (DE3) cells were transformed with pET24d-hTom40AΔ1-82 and grown in LB medium (20 ml) containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) at 37 °C in shaking flasks. This culture was used to inoculate LB medium (2 l) containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) for high level protein expression. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a cell density corresponding to an OD600 of 0.6. After 6 h of growth, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline and stored at −20 °C until further use. Mutant hToma40A protein (hTom40AΔ1-82mut) was expressed by the same procedure. For purification of wild-type and mutant Tom40, cells were thawed and 3 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride, 0.26 mg/ml lysozyme) were added per g cells. After lysis of membranes with 4 mg deoxycholate per g cells, DNaseI (12.5 units/g cells, Sigma-Aldrich) from bovine pancreas was added 40; 41. After incubation on ice for 20 min, inclusion bodies were separated from cell debris by centrifugation at 20000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Inclusion body pellets were washed with buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl and 100 mM NaCl, pH 8 and subsequently solubilized in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl), 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8, using a glass-glass homogenizer. To remove insoluble material the homogenate was centrifuged at 30000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C and supernatants were stored at 4 °C. One liter cell culture yielded 0.5 - 1 g of unprocessed protein. Protein concentrations were determined by UV absorbance using an extinction coefficient of ε280 of 29900 M−1cm−1 for hTom40AΔ1-82 and hTom40AΔ1-82mut 39.

For the over-expression of wild-type and mutant AfTom40, protein production was performed as for hTom40A with the difference that after induction the cells were further grown at 37 °C for 19 hours and cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellet was stored at − 20 °C until further use (~ 4 g/l of cell culture). The isolation of inclusion bodies was conducted under the same conditions for both AfTom40 wild-type and mutant and was based on the deoxycholic acid method according to 40; 41. Cells were thawn on ice and resuspended in 30 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl) for 10 gram of cells. After the addition of phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride and lysozyme to a final concentration of 0.13 mM and 0.26 mg/ml, respectively, solution was incubated on ice for 20 minutes and stirred occasionally. Then, solution was transferred into a water bath at a temperature of 37 °C. In the following, 40 mg of deoxycholic acid was added and solution was stirred until it became viscous. 250 units of Benzonase® (Novagen) were added at room temperature and suspension was stirred until it was no longer highly viscous. Solution was further spun down at 19.600 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Supernatant was discarded and pellet was resuspended in 100 ml of TNBP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF). After homogenization using a glass homogenizer, a clarifying spin was applied at 20.000 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Retrieved inclusion body pellet was resuspendend in 95 ml of TNTBP buffer (TNBP buffer containing 0.1 % (v/v) triton X-100) and homogenized on ice. A second clarifying spin was applied under the same conditions. Eventually, the pellet was washed with 100 ml of TNBP buffer and IB pellet was retrieved after centrifugation under the above named conditions. Washed IB pellet was then stored at − 20 °C until further use. Determination of protein concentration was conducted as for human Tom40 by using extinction coefficients39 of ε280 of 37025 M−1cm−1 for wild-type and mutant AfTom40, respectively.

Protein purification and folding

Inclusion bodies containing wild-type and mutated hTom40A (hTom40AΔ1-82 and hTom40AΔ1-82mut) were loaded onto an Ni-Sepharose HiTrap column (1 – 20 ml, GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 8. After washing the column with 2 column volumes of equilibration buffer, unspecifically bound proteins were removed with 20 mM imidazole. Then, hTom40A proteins were eluted with 300 mM imidazole, and fractions containing Tom40 were merged. Protein concentrations were adjusted to 5 mg/ml and samples were stored at 4 °C.

For refolding of wild-type and mutant hTom40A, purified protein in guanidine hydrochloride was diluted tenfold into 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, containing 0.5 % lauryldimethylamine-oxide (LDAO) and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After removal of aggregates by centrifugation at 100000 × g, samples containing refolded protein were concentrated to ~5 mg/ml by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. Samples were loaded onto Ni-Sepharose HiTrap columns (1 – 20 ml) previously equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.1 % LDAO and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Bound protein was eluted in the same buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. Final purification of protein was achieved by size exclusion chromatography using a Superose 12 column (GE Healthcare) which had been preequilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.1 % LDAO and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The purity of isolated protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, silver staining or Western blotting using antibodies against human Tom40 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

For refolding of wild-type and mutant AfTom40A the inclusion body pellets with both proteins were resuspended and homogenized in 6 ml of binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 8 M urea, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol) per gram cells. Solution was centrifuged at 19.600 × g and supernatant was loaded onto a Ni-Sepharose HiTrap column (1 – 5 ml, GE Healthcare) at room temperature. After column was washed with 10-15 column volumes of binding buffer, a gradient of 0-1 M imidazole was applied. Fractions containing AfTom40 were adjusted to a protein concentration of 6 mg/ml; and 6 mg of protein were refolded in 10 ml of refolding solution (20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.8 % (w/v) polyoxyethylene monolauryl ether (Brij35)). The refolded protein solution was dialyzed at 4 °C against 50-100 fold volumetric excess of refolding buffer using a 6-8 kDa MWCO Filter (Spectra/Por®). Purity was then determined throughout SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue. If necessary, a second purification step was conducted using the same conditions with the variation of exchanging 8 M urea against 0.8 % (w/v) Brij35 in the binding and elution buffer. Purified protein was then further dialyzed against 50-100 fold volumetric excess of refolding buffer and protein concentration was then adjusted to 0.2-0.4 mg/ml as needed.

Chemical cross-linking

For cross-linking experiments 40 μg of refolded and purified hTom40AΔ1-82 and hTom40AΔ1-82mut were suspended in 100 μl 20 mM NaH2PO4; pH 8 and incubated with 125 μM freshly prepared glutaraldehyde at 37 °C for 0-45 min. Aliquots were removed and cross-linking reactions were stopped by adding Tris pH 8 to a final concentration of 50 mM. Finally, cross-linking products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Polyclonal antibodies against hTom40A were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Heidelberg.

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism (UV-CD) spectroscopy measurements of refolded and purified wild-type and mutant hTom40A (~0.2 mg/ml) in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.5 % (w/v) LDAO, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol were performed using a Jasco J-715/815 spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan) in quartz cuvettes of 0.1 cm path length out of three independent protein preparations. Spectra were recorded at 25 °C from 185 to 260 nm with a resolution of 1.0 nm and an acquisition time of 20-100 nm/minute. Final CD spectrum was obtained by averaging five consecutive scans and corrected for background by subtraction of spectrum of protein-free samples recorded under the same conditions. Melting curves were recorded at constant wavelength at 216 nm for hTom40-A(Δ1-82) wild-type (wt) and mutant hTom40A from 25 to a maximum of 98 °C by applying a temperature ramp of 1 °C/minute. All CD samples were filtered (Rotilabo® filter, pore size 0.22 μm) and spun down at full speed with a bench top centrifuge for five minutes at room temperature (Biofuge fresco, Heraeus; Newport Pagnell) before measurements were conducted. Temperature readings displayed an error of ~1 °C, which was added to the experimental error. The mean residue ellipticity Θ(T) was calculated based on the molar protein concentration and the number of amino acid residues of regarding Tom40 proteins. Secondary structure content was determined using the CDpro package, namely CDSSTR, CONTIN/LL and SELCON 3 42; 43; 44.

AfTom40 proteins were measured under the same conditions at 0.1-0.4 mg/ml 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.8 % (w/v) Brij35.

To fit the unfolding curves of mutant Tom40s we assumed a two-state unfolding mechanism. The fraction fU(T) of unfolded protein was calculated according to fU(T)=[Θ(T)–ΘN(T)]/[ΘU(T)–ΘN(T)] and fitted to the sigmoid function fU(T)=1/[1+e(A/T–B)]. ΘN(T) and ΘU(T) represent the ellipticities of the native and unfolded molecule. At low and high temperatures, ΘN(T) and ΘU(T) increase linearly with temperature according to ΘN(T)=aT+b and ΘU(T)=cT+d. A and B are fitting parameters. If unfolding is fully reversible, they correlate with enthalpic and entropic changes of the unfolding reaction, respectively 45; 46 ; 47. Wild type Tom40 curves were fitted by superposition of two sigmoid functions assuming a three-state unfolding mechanism 48.

Tryptophan fluorescence measurements

Tryptophan fluorescence spectra of wild-type and mutant hTom40A (~0.15 mg/ml) were recorded by a FP-6500 spectrofluorimeter (Jasco Inc.) after 24 h of incubation in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 1 % (w/v) LDAO, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.35 to 7.0 M guanidine hydrochloride at 25 °C. Tryptophans were excited at 280 nm. Emission spectra were recorded between 300 and 400 nm with an integration time of 1 s. The band width for excitation and emission was set to 3 nm, respectively. Fluorescence spectra were evaluated by fitting background-corrected spectra I(λ) to the log-normal distribution I(λ)=I0 e−[ln2/ln2 ρ]·ln2[1+(λ−λmax)(ρ2−1)/ρΓ] 49; 50, where I0 is the fluorescence intensity observed at the wavelength of maximum intensity λmax, ρ is the line shape asymmetry parameter and Γ is the spectral width at half-maximum fluorescence intensity I0/2. Wild-type and mutant AfTom40 (~0.1 mg/ml) were investigated using the same parameters in 20 mM NaH2PO4 pH 7, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 0.8 % (w/v) Brij35.

To characterize denaturant induced folding and unfolding of mutant hTom40A and AfTom40 the fraction of unfolded protein fU(D) was fitted by the sigmoid function fU([D])=1/[1+e(A−B[D])/T]. If unfolding and folding are fully reversible, A correlates with the free energy of the protein that describes its stability at zero denaturant concentration. In this case B would be a measure of the dependence of free energy on denaturant concentration [D] 22; 23; 24. Chemically induced unfolding of wild-type Tom40s was processed as described for CD measurements.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dres. Uwe Gerken and Robin Ghosh for stimulating discussions and Dr. Kornelius Zeth for continuous support to F.M. We are also indebted to Dres. Andreas Kuhn and Andrei Lupas for access to the UV-CD and fluorescence spectrometer and Dr. Markus Bohnsack for advice. Financial support was provided by the Competence Network on “Functional Nanostructures” of the Baden-Württemberg Foundation to S.N. and D.L. (TP/A08), by the Landesgraduiertenkolleg Baden-Württemberg to F.M., by the NIH grants GM079804, GM086145 and NSF grant BMS0800257 to J.L., and by the Fulbright Commission and the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan to H.N.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haltia T, Freire E. Forces and factors that contribute to the structural stability of membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1228:1–27. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)00161-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanley A, Fleming K. The role of a hydrogen bonding network in the transmembrane beta-barrel OMPLA. J Mol Biol. 2007;370:912–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naveed H, Jackups R, Jr., Liang J. Predicting weakly stable regions, oligomerization state, and protein-protein interfaces in transmembrane domains of outer membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:12735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902169106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamian L, Naveed H, Liang J. Evolutionary conservation of lipid-binding sites in membrane proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembranes. 2011;1808:1092–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Gelder P, Saint N, Phale P, Eppens EF, Prilipov A, van Boxtel R, Rosenbusch JP, Tommassen J. Voltage sensing in the PhoE and OmpF outer membrane porins of Escherichia coli: role of charged residues. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:468–72. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phale PS, Philippsen A, Kiefhaber T, Koebnik R, Phale VP, Schirmer T, Rosenbusch JP. Stability of trimeric OmpF porin: the contributions of the latching loop L2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15663–70. doi: 10.1021/bi981215c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delcour A. Structure and Function of Pore-Forming beta-Barrels from Bacteria. J. Mol. Micro. Biotechnol. 2002;4:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evanics F, Hwang PM, Cheng Y, Kay LE, Prosser RS. Topology of an outer-membrane enzyme: Measuring oxygen and water contacts in solution NMR studies of PagP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8256–64. doi: 10.1021/ja0610075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahting U, Thieffry M, Engelhardt H, Hegerl R, Neupert W, Nussberger S. Tom40, the pore-forming component of the protein-conducting TOM channel in the outer membrane of mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1151–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill K, Model K, Ryan MT, Dietmeier K, Martin F, Wagner R, Pfanner N. Tom40 forms the hydrophilic channel of the mitochondrial import pore for preproteins. Nature. 1998;395:516–521. doi: 10.1038/26780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita JY, Mihara K, Oka T. Identification and characterization of a new tom40 isoform, a central component of mitochondrial outer membrane translocase. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2007;141:897–906. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Künkele KP, Heins S, Dembowski M, Nargang FE, Benz R, Thieffry M, Walz J, Lill R, Nussberger S, Neupert W. The preprotein translocation channel of the outer membrane of mitochondria. Cell. 1998;93:1009–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81206-4. issn: 0092-8674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H, Okazawa Y, Komiya T, Saeki K, Mekada E, Kitada S, Ito A, Mihara K. Characterization of Rat TOM40, a Central Component of the Preprotein Translocase of the Mitochondrial Outer Membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37930–37936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werhahn W, Jänsch L, Braun HP. Identification of novel subunits of the TOM complex of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2003;41:407–416. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayrhuber M, Meins T, Habeck M, Becker S, Giller K, Villinger S, Vonrhein C, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M, Zeth K. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pusnik M, Charriere F, Maser P, Waller RF, Dagley MJ, Lithgow T, Schneider A. The single mitochondrial porin of Trypanosoma brucei is the main metabolite transporter in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:671–80. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeth K. Structure and evolution of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins of beta-barrel topology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797:1292–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker L, Bannwarth M, Meisinger C, Hill K, Model K, Krimmer T, Casadio R, Truscott KN, Schulz GE, Pfanner N, Wagner R. Preprotein translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane: reconstituted Tom40 forms a characteristic TOM pore. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:1011–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malia TJ, Wagner G. NMR structural investigation of the mitochondrial outer membrane protein VDAC and its interaction with antiapoptotic Bcl-xL. Biochemistry. 2007;46:514–25. doi: 10.1021/bi061577h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackups R, Jr., Liang J. Interstrand pairing patterns in beta-barrel membrane proteins: the positive-outside rule, aromatic rescue, and strand registration prediction. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:979–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki H, Kadowaki T, Maeda M, Sasaki H, Nabekura J, Sakaguchi M, Mihara K. Membrane-embedded C-terminal segment of rat mitochondrial TOM40 constitutes protein-conducting pore with enriched beta-structure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:50619–50629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huyghues-Despointes BM, Pace CN, Englander SW, Scholtz JM. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein by hydrogen exchange. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;168:69–92. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-193-0:069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2138–48. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pace CN. Determination and analysis of urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Enzymol. 1986;131:266–80. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)31045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seitz T, Bocola M, Claren J, Sterner R. Stabilisation of a (betaalpha)8-barrel protein designed from identical half barrels. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:114–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keegan N, Ridley H, Lakey JH. Discovery of biphasic thermal unfolding of ompc with implications for surface loop stability. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9715–21. doi: 10.1021/bi100877y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahting U, Thun C, Hegerl R, Typke D, Nargang FE, Neupert W, Nussberger S. The TOM core complex: The general protein import pore of the outer membrane of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 1999;147:959–968. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Model K, Meisinger C, Kuhlbrandt W. Cryo-electron microscopy structure of a yeast mitochondrial preprotein translocase. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1049–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato H, Mihara K. Identification of Tom5 and Tom6 in the preprotein translocase complex of human mitochondrial outer membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:958–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayley H, Cremer PS. Stochastic sensors inspired by biology. Nature. 2001;413:226–30. doi: 10.1038/35093038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hocker B, Lochner A, Seitz T, Claren J, Sterner R. High-resolution crystal structure of an artificial (betaalpha)(8)-barrel protein designed from identical half-barrels. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1145–7. doi: 10.1021/bi802125b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seitz T, Thoma R, Schoch GA, Stihle M, Benz J, D’Arcy B, Wiget A, Ruf A, Hennig M, Sterner R. Enhancing the stability and solubility of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand-binding domain by high-throughput library screening. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:562–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherman EL, Go NE, Nargang FE. Functions of the small proteins in the TOM complex of Neurospora crasssa. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4172–82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bagos PG, Liakopoulos TD, Spyropoulos IC, Hamodrakas SJ. PRED-TMBB: a web server for predicting the topology of beta-barrel outer membrane proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W400–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ou YY, Chen SA, Gromiha MM. Prediction of membrane spanning segments and topology in beta-barrel membrane proteins at better accuracy. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:217–23. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang J. Experimental and computational studies of determinants of membrane-protein folding. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:878–84. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackups R, Jr., Liang J. Combinatorial analysis for sequence and spatial motif discovery in short sequence fragments. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2010;7:524–36. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2008.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackups R, Jr., Cheng S, Liang J. Sequence motifs and antimotifs in beta-barrel membrane proteins from a genome-wide analysis: the Ala-Tyr dichotomy and chaperone binding motifs. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:611–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilkins M, Gasteiger E, Bairoch A, Sanchez J, Williams K, Appel R, Hochstrasser D. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 1999;112:531–552. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-584-7:531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris TJ, Patel T, Marston FA, Little S, Emtage JS, Opdenakker G, Volckaert G, Rombauts W, Billiau A, De Somer P. Cloning of cDNA coding for human tissue-type plasminogen activator and its expression in Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Med. 1986;3:279–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engel J. DNA cloning: A practical approach. Acta Biotechnologica. 1987;9:254. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:252–60. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Structural composition of betaI- and betaII- proteins. Protein Sci. 2003;12:384–8. doi: 10.1110/ps.0235003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sreerama N, Woody RW. Computation and analysis of protein circular dichroism spectra. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:318–51. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Becktel WJ, Schellman JA. Protein stability curves. Biopolymers. 1987;26:1859–77. doi: 10.1002/bip.360261104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pace CN, Hebert EJ, Shaw KL, Schell D, Both V, Krajcikova D, Sevcik J, Wilson KS, Dauter Z, Hartley RW, Grimsley GR. Conformational stability and thermodynamics of folding of ribonucleases Sa, Sa2 and Sa3. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:271–86. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fersht A. Structure and mechanism in protein science: A guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. W.H. Freeman and Company; 1999. pp. 1–631. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng XY, Yang BS. An improved method for measuring the stability of a three-state unfolding protein. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2010;55:4120–4124. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladokhin AS, Jayasinghe S, White SH. How to measure and analyze tryptophan fluorescence in membranes properly, and why bother? Anal Biochem. 2000;285:235–45. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winterfeld S, Imhof N, Roos T, Bar G, Kuhn A, Gerken U. Substrate-induced conformational change of the Escherichia coli membrane insertase YidC. Biochemistry. 2009;48:6684–91. doi: 10.1021/bi9003809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spyropoulos IC, Liakopoulos TD, Bagos PG, Hamodrakas SJ. TMRPres2D: high quality visual representation of transmembrane protein models. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3258–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Measuring the conformational stability of a protein. in Protein Structure A Practical Approach. 1997:299–321. Pace, C. & Scholtz, J. (1997) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.