A female high school soccer athlete reacts to a defender, plants her leg, cuts to the left without contact, feels her leg give out, hears a pop, and has acute pain. She is unable to walk off the field or return to play. That evening her knee progressively swells. The next day she presents to your office. How should her case be evaluated and treated?

The Clinical Problem

The passage in 1972 of Title IX legislation, which guarantees equal access to athletics for both sexes at any high school or college receiving federal funds, has led to an exponential rise in female participation in sports. While this has resulted in many benefits, including promoting physical fitness and fostering team building behavior, it has also led to an increase in sports related injuries in female athletes, in particular anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears. (Figure 1)

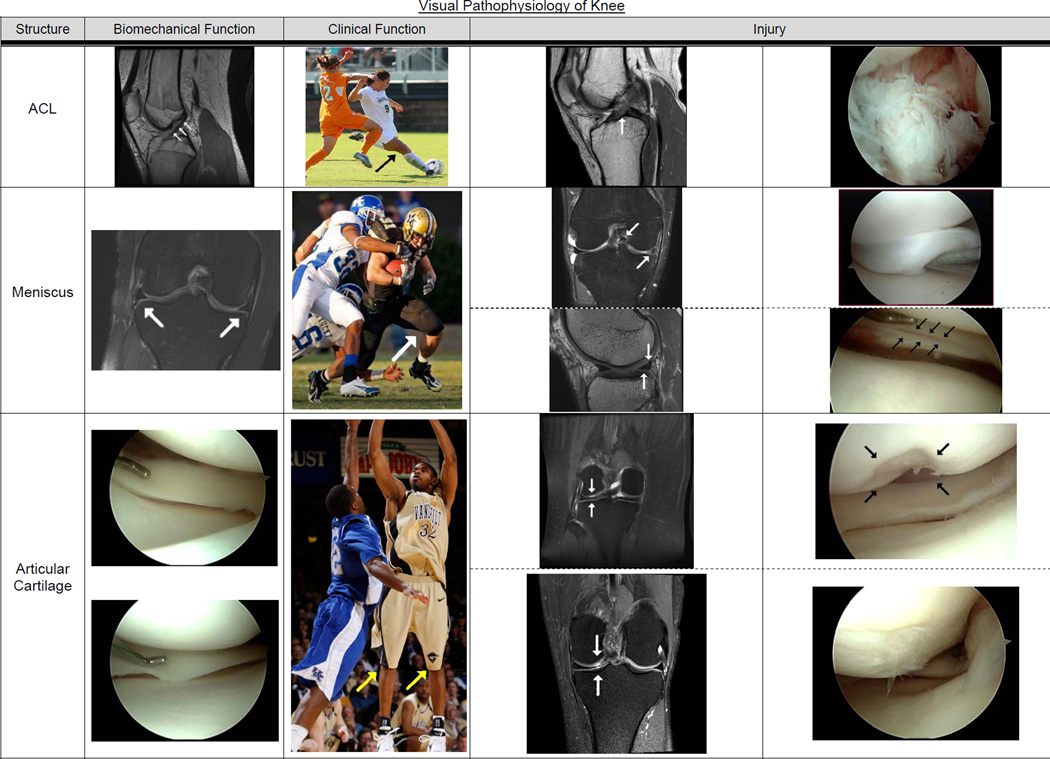

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of Knee.

This figure contains MRIs, action photography, and operative pictures representing normal knees and tears to the ACL, meniscus, and articular cartilage.

Row 1: Presents the ACL, shown from left to right. Arrows on the first MRI depict a normal ACL. Next is an action shot of a women’s soccer player planting her right leg to decelerate, pivot, and kick with her left leg. The second MRI shows the ACL tear as a disruption of the normal straight black contour of an ACL, and the operative picture indicates a completely torn ACL “balled up” in the front of the notch.

Row 2: Meniscus -- The first MRI shows the medial and lateral menisci in the coronal plane (view from the front) as triangular black structures between femoral condyles above and tibial plateau below to distribute loads between meniscus and articular cartilage. The function of “load sharing” is depicted in the football running back with two players tackling him. Meniscus tears include a bucket handle tear shown above where a large portion is displaced into the notch (see arrow), which locks the knee (restricts motion). The corresponding operative picture (immediately to right) shows a large piece or bucket handle displaced blocking the normal view medial compartment. The lateral view by the arrow shows one of the most common acute tears of the meniscus as a white line straight through the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. In the operative photograph the arrows indicate the tear.

Row 3: The articular cartilage is a few-millimeter thick avascular covering over the femur and tibia (not unlike the rubber on a tire covering the steel belts). This surface is nearly frictionless by design to dissipate impact loads. The percentage of load between the meniscus versus the articular cartilage depends on which meniscus, degree of knee flexion, and integrity of the ACL. The basketball player demonstrates the ability of the articular cartilage to dissipate acute loads when landing from a jump. Articular cartilage pathology can be either focal defects as depicted on top or degenerative or arthritis as shown below. For the focal defect seen on MRI with corresponding intraoperative picture, there are current treatments available for restoring short-term function. However, once degenerative arthritis develops as shown by abnormal signal on an MRI and fibrillation shown intraop (contrast with the normally perfectly smooth articular surface), there are no effective treatments yet. The ACL tears can be reconstructed and meniscus tears either repaired or resected, enabling the athlete to return to play. The development of arthritis is the end of an athlete’s career regardless of age.

Figure edited by Alex Bottiggi

All athletic photographs courtesy of Rod Williamson, Vanderbilt Athletic Sports Information Director

The ACL is the most commonly injured ligament in the body for which surgery is frequently performed. It is estimated that 175,000 ACL reconstructions were performed in the year 2000 in the US,1 at a cost of more than two billion dollars;1 this number continues to increase. Incidence rates for tears are difficult to assess because some injuries remain undiagnosed. A recent study at West Point, where injuries are consistently reported, demonstrated an incidence of ACL tears over four years of 3.2% for men versus 3.5% for women.2 When considering sports or activities in which both sexes participated, women had a significantly higher incidence ratio than men (incidence ratio1.5 (95% confidence interval, 1.3–2.2).3 The majority of ACL tears (67% in men and almost 90% in women) occurred without contact. In other studies, the injury rate in female athletes has ranged from two to six times the rate in male athletes depending on the sport studied.4–7 The increased risk of ACL tear in female athletes remains incompletely understood but has been attributed to several factors, including mechanical axis (leg alignment, ie with females on average more knock-kneed [valgus]) and notch width (females may have less space for ACL), hormonal factors (increased risk during first half [preovulatory] of menstrual cycle),8 and neuromuscular control.6, 9

Besides the immediate associated morbidity and costs, an ACL tear significantly increases the risk for premature knee osteoarthritis (OA).3, 10 It is estimated that 50% of patients with ACL tears develop osteoarthritis 10 to 20 years later, while still young.3, 11, 12

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

DIAGNOSIS

A careful history and physical exam will frequently allow an accurate diagnosis of an ACL tear without the need for additional testing or evaluation. An “isolated” ACL tear occurs less than 10% of the time, and assessment is needed for associated injuries; the prevalence of associated meniscus injuries is 60% to 75%;7, 13, 14 articular cartilage injuries, up to 46%,7, 13–15 subchondral bone injuries (i.e., “bone bruises” on MRI), 80%;16–18 and complete collateral ligament tears (medial or lateral), 5 to 24%.14, 16, 19 Table 1 summarizes the functions of the three major intra-articular knee structures (ACL, meniscus, and articular cartilage) and manifestations of injury to these structures.

Table 1.

Function, Type of Injury, and Initial Evaluation of Commonly Injured Knee Structures

| Knee Structure | Biomechanical Function |

Clinical Function | Injury Type |

Symptomsa | Signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) | Prevents anterior and rotational motion of tibia relative to femur | Stabilizes knee for cutting and pivoting | Tear, primarily rupture | “Giving out” while cutting and pivoting | Positive Lachman and pivot shift |

| Meniscus (medial and lateral) | Decrease force per unit area on articular cartilage (distribute load) | Protects articular cartilage from premature degeneration or osteoarthritis (OA) | Tear, both partial and complete | Mechanical symptoms, e.g. catching, locking | Joint line pain, effusion |

| Articular Cartilage | Allows for “near” frictionless gliding surface and impact disipation | Allows for painless and near effortless active motion and impact | Focalb or OAc |

None or pain | None or loose body |

| Pain, stiffness, swelling | Joint line pain, effusion |

Key:

= symptoms most specific for diagnosis

= focal = isolated to a small area like femoral condyle. Focal defects are believed to be predictive of OA.

= OA = osteoarthritis = regional loss of articular cartilage structure and function

Key points of the history suggesting ACL tear include a non-contact mechanism of injury, identification of a "pop", early occurrence of swelling (as result of bleeding (hemarthrosis) from rupture of the vascular ACL), and inability to continue to participate in the game or practice after the injury. Collateral ligament tears usually do not result in swelling, and frequently patients with partial posterior ligament tears (PCL) can continue to play. Meniscus tears are associated with a delayed onset of swelling (commonly the next day).

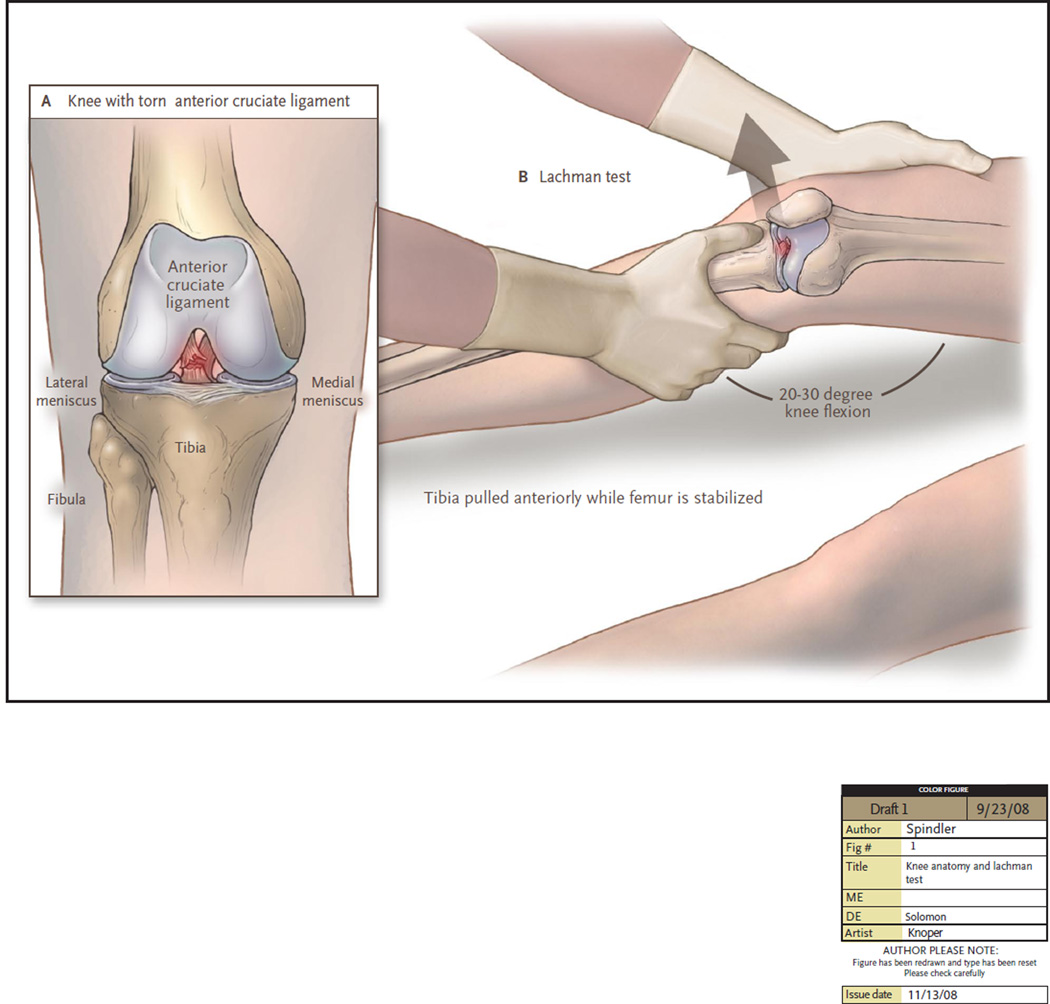

Two physical exam maneuvers-- the Lachman test and the pivot shift test-- are useful in assessment for ACL tear. (Figure 2). In a recent meta-analysis of 28 studies, the pooled sensitivity and specificity of the Lachman test for ACL tear was 85% and 94%, respectively.20 For the pivot shift, specificity was high (98%) but sensitivity was low (24%). However, when the diagnosis by history and physical examination is clearly established an MRI is optional before proceeding to ACL reconstruction in an athlete.

Figure 2. The Lachman Test.

The most popular variation of “Lachman’s test” for ACL tears requires a supine relaxed patient. The examiner has one hand on the outside of the thigh, just above the knee, stabilizing the femur in slight external rotation and elevated off the bed to produce a knee flexion angle of 20–30 degrees. The second hand is placed on anteromedial tibia with thumb on flat bony border of tibia. Once the patient is relaxed the hand on the tibia attempts to displace the tibia anteriorly in relation to the stabilized femur. First the normal knee is examined as a control with a positive test on the injured knee the absent sensation of a solid stop (“endpoint”) to anterior displacement of tibia (called “soft endpoint”). Additional supporting information is an increased displacement of tibia anteriorly versus contralateral normal knee. The pivot shift has many variations but reproduces the subluxation of the tibia on the femur that the athlete feels clinically and is beyond the scope of this text.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is generally used to confirm the diagnosis. According to a recent systematic review, utilizing arthroscopy as the gold standard, MRI had a sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 95%, and accuracy of 93% for ACL tear.21

Management

The majority of patients with a torn ACL can walk normally and can perform straight plane activities including stair climbing, biking, and jogging. Surgical treatment is indicated if the patient has a sensation of instability in normal activities of daily living, or wants to resume activities that involve cutting and pivoting; among these are football, soccer, basketball, lacrosse, singles tennis, and mogul skiing. Occupations such as firefighting, law enforcement, and some construction jobs also require an ACL stabilized knee.

Whether or not surgical intervention is pursued, the acute management of an ACL tear should focus on reducing hemarthrosis (with rest, ice, compression, elevation [RICE], and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories), regaining normal range of motion, reinitiating quadriceps control, and restoring normal gait all of which usually takes on average 2 to 4 weeks from the time of the injury.

Surgical approaches

The surgical approach to ACL tears for the last two decades has involved ACL reconstruction, using a graft (a piece of tendon) through tunnels drilled into the tibia and femur at insertion points of the ACL to approximate normal anatomy, with the goal of eliminating ACL instability. Reconstruction is indicated rather than repair, as randomized trials have demonstrated that ACL repair is no better than nonoperative treatment22 and that ACL reconstruction significantly improves knee stability and the likelihood of return to preinjury activity over repair alone or repair with augmentation (insertion of a tendon graft or synthetic graft).23 In addition, randomized trials of ACL reconstruction have shown significantly fewer subsequent meniscus tears requiring surgery at two years versus nonoperative management,24, whereas the addition of augmentation to ACL reconstruction offered no benefit over reconstruction alone.

A systematic review of four randomized trials has demonstrated similar outcomes using endoscopic (single-incision) versus rear (two-incision) entry.25 Either patellar tendon (i.e., bone-tendon-bone) or hamstring tendon may be used. A systematic review of nine randomized controlled trials involving autografts found that these approaches yielded comparable results, including anterior-posterior laxity, isokinetic quadriceps and hamstring strength, anterior knee pain, and clinical outcome or rating scores26, although the four trials that evaluated pain on kneeling found an increase in pain with harvesting the patellar tendon, as compared with the hamstring. The most recent meta-analyses27, 28 of trials comparing these 2 autograftsobserved absolute differences between 3 and 9% on six categories with no consistent results favoring one type of autograft. Patellar tendon grafts had more stability (4% less positive Lachman, 5% less positive pivot shift), 8% greater “normal” knees (so-called International Knee Documentation Committee [IKDC] group A), and 9% greater return to pre-injury activity. However, only the 4% less positive Lachman was statistically significant. Hamstring grafts had significantly less anterior knee pain by 9% and significantly less extension deficit by 3%. No validated scales were utilized for anterior knee pain, activity level, or overall knee rating. Recently designed and validated patient-reported outcomes have not been compared. Thus comparable outcomes can be expected from both autografts. These results are a negative Lachman and pivot shift ~70–75%, less than ~10% extension loss, less than ~20% anterior knee pain, with two-thirds return to pre-injury activity, but only ~40% will be classified overall as normal knees by IKDC.27, 28

Randomized trials are lacking to inform the choice of allograft versus autograft for ACL reconstruction. The best available evidence is from seven observational studies29–35 showing no significant differences in patient-reported outcomes, instrumented laxity, and donor site symptoms. However the failure rate at two years was significantly higher for allografts (9 of 158) than autografts (2 of 167) (p=0.03). Thus it is prudent to avoid allografts where possible in young athletes. The means of graft fixation (i.e. the technique or device used to secure the graft into the tibial and femoral tunnels) has not affected outcomes, including stability, range of motion, strength, and clinical assessments.

Immediate complications of ACL reconstruction are uncommon but include infection, deep venous thrombosis, and nerve injury.26 Graft failure has been reported to occur in 3.6% of cases at two years, with no significant differences noted between hamstring graft and patellar tendons. Additional arthroscopic surgery was necessary in 14.7% of patients in one series, and included debridement of scar tissue and treatment of meniscus and articular cartilage. In a prospective cohort study, the risk of re-tearing the ACL reconstruction graft was the same as the risk of tearing the contralateral normal knee ACL (3.0% for each).36

Management of associated injuries

The presence of other knee injuries may adversely affect outcomes after ACL reconstruction. The risk of OA appears to be increased in patients who have had an associated mensical tear or cartilage injury. Detailed discussion of the techniques to treat these associated injuries is beyond the present scope, but case series indicate high success rates for treating meniscal injuries. Longitudinal tears in the vascular zone (~peripheral one-third) undergo repair, which has been reported to result in an 87% success rate (as defined by no need for re-operation for clinical symptoms) using current techniques.37 Tears in the avascular zone (central two-thirds) are treated with partial meniscectomy. There is currently no effective treatment for articular cartilage injuries that do not penetrate subchondral bone, other than debridement of unstable pieces; in cases where a lesion extends to bone, a variety of restorative procedures are available.

REHABILITATION

A recent systematic review38, 39 of 54 randomized clinical trials evaluated a variety of rehabilitation techniques and “assistive devices”. Among its conclusions were that: (1) immediate postoperative weight-bearing does not adversely affect subsequent knee function; (2) in the motivated patient a self-directed home therapy program with initial patient education and monitoring is as effective as regular physical therapy visits; (3) the use of continuous passive motion machines, compared to no use, does not improve outcome; (4) the use of postoperative functional bracing versus no brace does not improve the outcomes; (5) closed kinetic chain exercises (exercises with foot planted on ground or force plate, ie leg press or squat) result in better stability than open chain (foot not planted, ie knee extensions); (6) an accelerated rehabilitation program (return to sport at six months) resulted in no increase in knee laxity as compared to a delayed rehabilitation program.

PREVENTION

Recognition of the disproportionate risk of ACL tears among female athletes participating in the same sports as male athletes at similar competition levels has led to the development of prevention strategies for female athletes. Modifiable factors that are assocated with injury (in both men and women) include the sport, competition level, contact, footwear, and playing surface. Primary prevention strategies evaluated in controlled trials in female athletes have involved a comprehensive program focused on neuromuscular training, including plyometrics (use of muscle stretching just before rapid contraction), balance, and strengthening exercises performed more than once per week for a minimum of six weeks. Three of six trials of such interventions in one meta-analysis9 showed a significantly reduced risk of ACL tears, with an overall odds ratio for ACL tear across the 6 trials of 0.40 (95% CI 0.26–0.61). The identification of ACL deficient patients who can function normally without reconstruction (termed “copers”) may provide insights into their neuromuscular adaptation patterns which may be applied to improve prevention strategies.)40–42

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

The optimal treatment of patients with partial ACL tears, skeletally immature patients with tears, and patients whose ACL graft has failed remains unclear; multicenter observational studies of these patients are ongoing. The risk of future OA associated with ACL tear, and potential modifiers of this risk, including meniscus and articular cartilage injuries and their treatments, remain incompletely understood, and it remains unclear how best to minimize this risk. Further studies are needed to define appropriate nonoperative treatment of ACL tear, optimal time to return to sports, and the influence of hormones on the risk of ACL. The potential role of tissue engineering to enable successful repair of associated injuries (including avascular zone meniscus tear, or articular cartilage injuries) is unclear.

GUIDELINES FOR ACL TREATMENT

There are to our knowledge no published professional guidelines for the management of ACL tear.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

An athlete’s injured knee should be evaluated by a thorough physical examination when an ACL tear is suspected by the history of a pop, noncontact pivoting mechanism, or immediate swelling, as in the case described in the vignette. A positive Lachman test and/or pivot shift is consistent with the diagnosis, athough these tests (particularly the pivot shift test) may be equivocal even when a tear is present. If the diagnosis is uncertain or associated injuries are suspected, then an MRI is indicated. Indications for ACL reconstruction include a desire for future participation in sports and instability in activities of daily living. Randomized trials support either a single- or two-incision surgical approach and the use of an autograft from either the hamstring or patellar tendon, using the appropriate fixation system for the chosen autograft. Rehabilitation should be supervised by a rehabilitation professional and includes initial weight bearing with crutches and a closed chain based exercise program, with a usual aim to return to play at six months. Neuromuscular training programs may reduce the risk of ACL tears in female athletes (and other high risk populations).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Review of manuscript: Frank E. Harrell, Jr., PhD, and Michelle Shepard, MS

Editorial assistance: Lynn S. Cain

Funding (KPS): Kenneth D. Schermerhorn Endowed Chair and NIH Grant -- NIAMS #R01AR053684-01 A1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Gottlob CA, Baker CL, Jr, Pellissier JM, Colvin L. Cost effectiveness of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999:272–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mountcastle SB, Posner M, Kragh JF, Jr, Taylor DC. Gender differences in anterior cruciate ligament injury vary with activity: epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in a young, athletic population. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1635–1642. doi: 10.1177/0363546507302917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1756–1769. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agel J, Arendt EA, Bershadsky B. Anterior cruciate ligament injury in national collegiate athletic association basketball and soccer: a 13-year review. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:524–531. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjordal JM, Arnoy F, Hannestad B, Strand T. Epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in soccer. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:341–345. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 1, mechanisms and risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:299–311. doi: 10.1177/0363546505284183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piasecki DP, Spindler KP, Warren TA, Andrish JT, Parker RD. Intraarticular injuries associated with anterior cruciate ligament tear: findings at ligament reconstruction in high school and recreational athletes: An analysis of sex-based differences. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:601–605. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310042101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewett TE, Zazulak BT, Myer GD. Effects of the menstrual cycle on anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:659–668. doi: 10.1177/0363546506295699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hewett TE, Ford KR, Myer GD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female athletes: Part 2, a meta-analysis of neuromuscular interventions aimed at injury prevention. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:490–498. doi: 10.1177/0363546505282619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, Fithian DC, Rossman DJ, Kaufman KR. Fate of the ACL-injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632–644. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, Fleming BC, Nichols CE. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part I. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1579–1602. doi: 10.1177/0363546505279913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beynnon BD, Johnson RJ, Abate JA, Fleming BC, Nichols CE. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries, part 2. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1751–1767. doi: 10.1177/0363546505279922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeHaven KE. Diagnosis of acute knee injuries with hemarthrosis. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:9–14. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noyes FR, Bassett RW, Grood ES, Butler DL. Arthroscopy in acute traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee. Incidence of anterior cruciate tears and other injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:687–695. 757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowers AL, Spindler KP, McCarty EC, Arrigain S. Height, weight, and BMI predict intra-articular injuries observed during ACL reconstruction: evaluation of 456 cases from a prospective ACL database. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spindler KP, Schils JP, Bergfeld JA, et al. Prospective study of osseous, articular, and meniscal lesions in recent anterior cruciate ligament tears by magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:551–557. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vellet AD, Marks PH, Fowler PJ, Munro TG. Occult posttraumatic osteochondral lesions of the knee: prevalence, classification, and short-term sequelae evaluated with MR imaging. Radiology. 1991;178:271–276. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1984319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speer KP, Spritzer CE, Bassett FH, 3rd, Feagin JA, Jr, Garrett WE., Jr Osseous injury associated with acute tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:382–389. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaeding C, Farr J, Kavanaugh T, Pedroza A. A prospective randomized comparison of bioabsorbable and titanium anterior cruciate ligament interference screws. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267–288. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford R, Walley G, Bridgman S, Maffulli N. Magnetic resonance imaging versus arthroscopy in the diagnosis of knee pathology, concentrating on meniscal lesions and ACL tears: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2007;84:5–23. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg R, Balkfors B, Nilsson B, Westlin N. Operative versus non-operative treatment of recent injuries to the ligaments of the knee. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1120–1126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engebretsen L, Benum P, Fasting O, Molster A, Strand T. A prospective, randomized study of three surgical techniques for treatment of acute ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:585–590. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson C, Odensten M, Good L, Gillquist J. Surgical or non-surgical treatment of acute rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament. A randomized study with long-trm follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:965–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George MS, Huston LJ, Spindler KP. Endoscopic versus rear-entry ACL reconstruction: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:158–161. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31802eb45f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spindler KP, Kuhn JE, Freedman KB, Matthews CE, Dittus RS, Harrell FE., Jr Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction autograft choice: bone-tendon-bone versus hamstring: does it really matter? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1986–1995. doi: 10.1177/0363546504271211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biau DJ, Tournoux C, Katsahian S, Schranz P, Nizard R. ACL reconstruction: a meta-analysis of functional scores. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;458:180–187. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31803dcd6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biau DJ, Tournoux C, Katsahian S, Schranz PJ, Nizard RS. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autografts versus hamstring autografts for reconstruction of anterior cruciate ligament: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:995–1001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38784.384109.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett G, Stokes D, White M. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients older than 40 years: allograft versus autograft patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1505–1512. doi: 10.1177/0363546504274202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang SKY, Egami DK, Shaieb MD, Kan DM, Richardson AB. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: allograft versus autograft. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:453–462. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harner CD, Olson E, Irrgang JJ, Silverstein S, Fu FH, Silbey M. Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: 3- to 5-year outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996:134–144. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199603000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleipool AE, Zijl JA, Willems WJ. Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with bone-patellar tendon-bone allograft or autograft. A prospective study with an average follow up of 4 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;6:224–230. doi: 10.1007/s001670050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson RK, Shelton WR, Bomboy AL. Allograft versus autograft patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A 5-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:9–13. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.19965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saddemi SR, Frogameni AD, Fenton PJ, Hartman J, Hartman W. Comparison of perioperative morbidity of anterior cruciate ligament autografts versus allografts. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:519–524. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Victor J, Bellemans J, Witvrouw E, Govaers K, Fabry G. Graft selection in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction--prospective analysis of patellar tendon autografts compared with allografts. Int Orthop. 1997;21:93–97. doi: 10.1007/s002640050127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wright RW, Dunn WR, Amendola A, et al. Risk of tearing the intact anterior cruciate ligament in the contralateral knee and rupturing the anterior cruciate ligament graft during the first 2 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective MOON cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1131–1134. doi: 10.1177/0363546507301318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spindler KP, McCarty EC, Warren TA, Devin C, Connor JT. Prospective comparison of arthroscopic medial meniscal repair technique: inside-out suture versus entirely arthroscopic arrows. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:929–934. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310063101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright RWPE, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Kaeding C, Kuhn JE, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Spindler KP, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Williams GN. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part II: open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, accelerated rehabilitation, and miscellaneous topics. J Knee Surg. 2008;21:225–234. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright RWPE, Fleming BC, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Kaeding C, Kuhn JE, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Spindler KP, Wolcott M, Wolf BR, Williams GN. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation: part I: continuous passive motion, early weight bearing, postoperative bracing, and home-based rehabilitation. J Knee Surg. 2008;21:217–224. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 1, outcomes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:40–47. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hurd WJ, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. A 10-year prospective trial of a patient management algorithm and screening examination for highly active individuals with anterior cruciate ligament injury: Part 2, determinants of dynamic knee stability. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36:48–56. doi: 10.1177/0363546507308191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rudolph KSEM, Axe MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. 1998 Basmajian Student Award Paper: Movement patterns after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a comparison of patients who compensate well for the injury and those who require operative stabilization. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 1998;8:349–362. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(97)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]