Abstract

Aim

To examine self-efficacy and program exposure as possible mediators observed treatment effects for a Web-based tobacco cessation intervention.

Design

The ChewFree trial used a two-arm design to compare tobacco abstinence at both the 3- and 6-month follow-up for participants randomized to either an Enhanced intervention condition or a Basic information-only control condition.

Setting

Internet in US and Canada.

Participants

Our secondary analyses focused on 402 participants who visited the Web-based program at least once, whose Baseline self-efficacy rating showed room for improvement, who reported that they were still using tobacco at the 6-week assessment, and for whom both 3- and 6-month follow-up data were available.

Intervention

An Enhanced Web-based behavioral smokeless tobacco cessation intervention delivered program content using text, interactive activities, testimonial videos and an ask-an-expert forum and a peer forum. The Basic control condition delivered tobacco cessation content using static text only.

Measurements

Change in self-efficacy and program exposure from baseline to 6-weeks were tested as simple and multiple mediators on the effect of treatment condition on point-prevalence tobacco abstinence measured at 3- and 6-months follow-up.

Findings

While both participant self-efficacy and program exposure satisfied the requirements for simple mediation only self-efficacy emerged as a mediator when we used the more robust test of multiple mediation.

Conclusions

Results confirm the importance of self-efficacy change as a likely underlying mechanism in a successful Web-based behavioral intervention. While program exposure was found to be a simple mediator of tobacco abstinence, it failed to emerge as a mediator when tested with self-efficacy change in a multiple mediator test suggesting that self-efficacy and program exposure share a complex, possibly reciprocal relationship with the tobacco abstinence outcome. Our results underscore the utility of searching for mediators in research on Web-based interventions.

Keywords: Internet, tobacco cessation, smokeless, Web, mediators

INTRODUCTION

Given its prevalence and health consequences, smokeless tobacco (ST) – which includes chewing tobacco and snuff – remains a significant public health problem [1,2]. The reach and convenience of Web-based behavioral interventions seem particularly appropriate since clinic-based ST cessation programs are generally not available – particularly to chewers located in rural settings. The Web-based ChewFree randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that participants assigned to an Enhanced (highly-interactive) condition were significantly more likely to be tobacco abstinent at both 3- and 6-months post-enrollment than participants who were assigned to a Basic control (textual information) condition [3].

We describe secondary analyses of data from the ChewFree.com project that explore mechanisms that might explain the observed treatment effect. We explore two a priori putative mediators: participant self-efficacy and the extent to which participants viewed the content of the Web-based intervention (program exposure).

Self-efficacy

Components of the ST cessation intervention were based on Social Cognitive Theory [4,5] as it has been applied to tobacco abstinence [6,7]. The intervention was designed to encourage participants to use strategies that address behavior, cognition, and environment [8,9] and thereby enhance participant self-efficacy and increase tobacco abstinence. Other research has found self-efficacy to act as a mediator across a wide variety of behavioral changes [10–14] including for tobacco cessation [15–19].

Program exposure

One defining characteristic of research on Web-based behavior change interventions is its focus on participant engagement – a key ingredient of which involves analysis of program exposure data that are collected unobtrusively as participants visit the program website. Two key exposure measures include the frequency and the duration of participants’ online visits to view program content [20]. Participants in Web-based programs typically are able to control how much or little they use a website and several such tobacco cessation studies have shown that participants make relatively few visits to the site [20]. More frequent and longer visits are presumed to enable more learning of coping skills and therefore increase self-efficacy. Alternatively, more exposure might reflect stronger motivation for behavior change. In either case, we would expect exposure to be positively related to outcome.

METHODS

ChewFree RCT

The ChewFree trial [21] used a two-arm design to compare tobacco abstinence at both the 3- and 6-month follow-up for participants randomized to either: (a) an Enhanced intervention condition (text, graphics, interactive activities, testimonial videos and an ask-an-expert forum and a peer forum); or (b) a Basic information-only control condition (online self-help ST cessation booklet, overview of cessation resources, and annotated list of other helpful websites for tobacco cessation). One of the aims of the study was to test for mediators that might represent underlying mechanisms of observed changes.

Participant recruitment and characteristics

The ChewFree participant recruitment campaign used news releases to print and broadcast media, advertising on Google and in newspapers and magazines, placement of ChewFree.com links on other websites, and direct mail to health care and tobacco control professionals [22]. Participant eligibility criteria included: use of ≥ 1 ST can/week for at least 1 year; interest in quitting ST; ≥ 18 years of age; ability to read English; resident of U.S. or Canada; use of personal e-mail account ≥ 1/week; willingness to provide name, home address, and phone number; ability to read and write English; and completion of Informed Consent Statement approved by Institutional Review Board of Oregon Research Institute. A total of 2523 participants randomized either to the Enhanced intervention condition (N= 1,260) or the Basic control conditions (N= 1,263) did not differ in terms of these Baseline participant characteristics.

Consistent with many studies of Web-based behavioral interventions [23], the ChewFree trial experienced substantial attrition at the follow-up assessments [3]: 52% at 3 months, 55% at 6 months, and 66% attrition when we required participation at both 3 and 6 months.

MEASURES

Tobacco abstinence outcome

Self-reported measures of smokeless tobacco use, cigarette smoking, and pipe or cigar smoking were obtained at all assessment points by asking about 7-day point prevalence use of tobacco products (ST, cigarettes, pipes, and cigars). Repeated point prevalence of self-reported tobacco abstinence at both the 3- and 6-month assessment was our dependent variable.

Self-efficacy

Participant self-efficacy was measured at Baseline as well as at follow-up assessments in both conditions by asking: How confident are you that you will not be using smokeless tobacco a year from now? using a five-point Likert scale: 0= Not at all, 2= Somewhat, and 4= Completely. Change in self-efficacy was computed by subtracting the rating obtained at Baseline from the rating obtained at the 6-week assessment. An increase in self-efficacy across these two time points would be described by a positive number, a reduction in self-efficacy would be indicated by a negative number, and no change would be represented by a zero.

Program exposure

Each participant’s username and password were obtained during their log-in which permitted unobtrusive tracking of the number and duration of each of visit to access program content [20]. We considered only exposure data for the period prior to the 6-week assessment. After we established that standardized versions of number and duration of visits were highly correlated (r= .67), we used a composite exposure variable defined as the mean of the Z-score transformations of visits (number) and duration (minutes).

Participant selection and characteristics

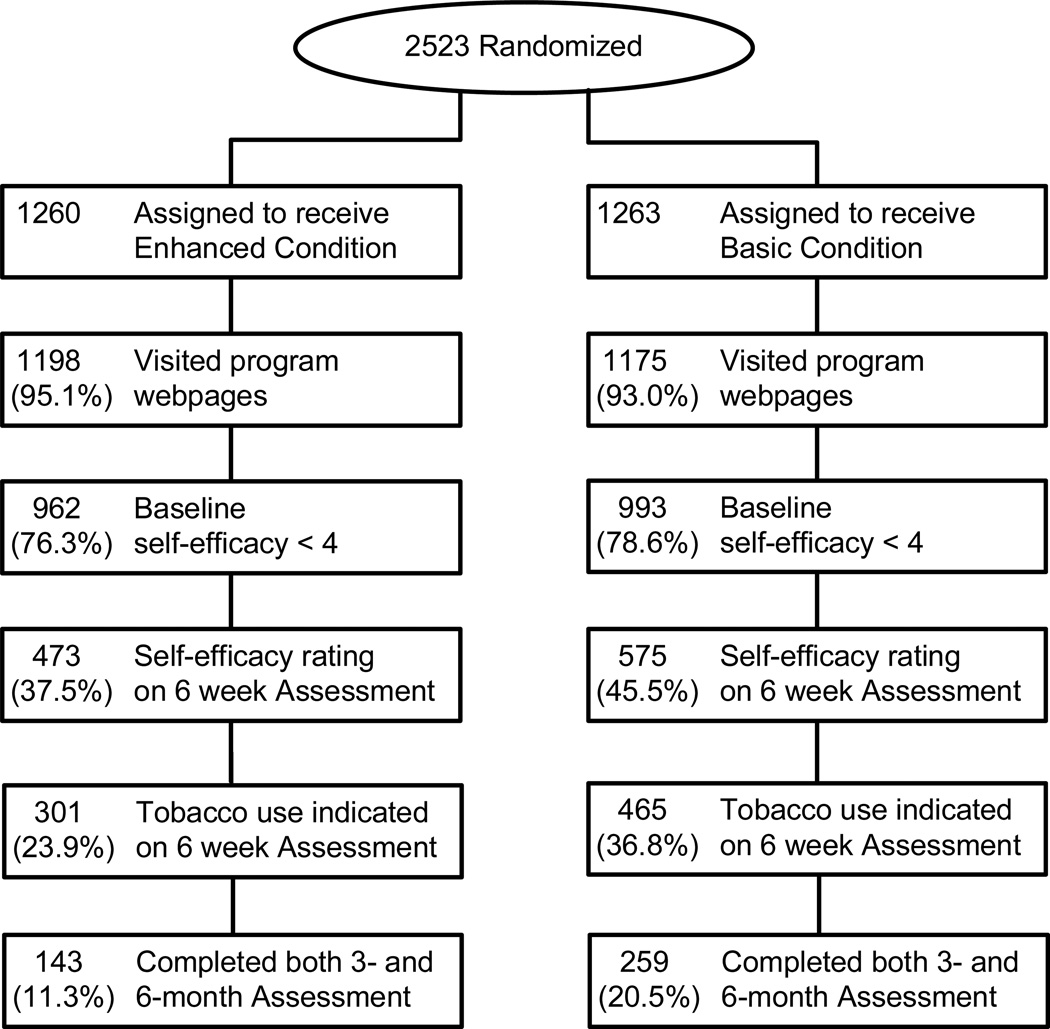

For the mediation analysis we used a subsample of ChewFree participants for whom data were available on all of the key variables. We included participants whose Web-server data indicated that they had visited the Web-based program for at least a single occasion. Because we were interested in the possible mediation effects of participant improvement in self-efficacy, we included participants who could improve their self-efficacy, i.e., those with a Baseline self-efficacy rating of less than 4 (ceiling level of “complete confidence”). In order to enhance the probability that change in self-efficacy predated the change in tobacco use rather than reflected it – thus satisfying the temporal precedence requirement for mediation [24,25] – we limited our analysis to those participants who reported that they were still using tobacco at the 6-week assessment. Finally, we included only those individuals for whom both 3- and 6-month follow-up data were available. These inclusion criteria yielded a subsample of 402 participants (Enhanced Condition N= 143 and Basic Condition N= 259) used in the current analyses (see Figure 1) of whom 11.4% (46/402) were tobacco abstinent at both the 3- and 6-month follow-up assessments. The imbalance in number of participants by condition is associated with the fact that fewer participants in the Enhanced condition reported using tobacco at 6 weeks and, further, that the Enhanced condition experienced more overall attrition [3].

Figure 1.

Final sample of 402 participants by condition and inclusion criteria

The subset of 402 participants did not differ by condition at baseline in terms of age (Mean= 37.1, SD= 9.2), gender: (Male= 96.5%), marital status (69.7% married); rurality: (39.3% rural using RUCAS measure [26]), days their ST tin lasted (Mean= 2.2, SD= 1.5), years of ST use (Mean= 18.8, SD= 9.1), use of ST within first 30 minutes of waking (54%), current smoking (5.5%), ST quit attempt in last year (69.4%), and readiness to quit ST (Mean= 7.8, SD= 1.7; based on an adaptation of the contemplation ladder [27] that used a ten-point Likert scale with 0= No thought of quitting, 2= Think I need to consider quitting someday, 5= Think I should quit but not quite ready, 8= Starting to think about how to change my patterns of using chew or snuff, 10= Taking action to quit (for example, cutting down, enrolling in program).

Statistical analyses

Condition Comparisons

We used contingency table analysis to compute the Odds Ratios for the association between treatment condition and tobacco abstinence outcome (repeated point prevalence at both 3 and 6 month assessments).

Mediation analyses

We initially used the widely-used “causal steps” mediation test outlined by Baron and Kenny [28]. Referencing the paths depicted in Figure 2, we used linear regression to determine whether treatment condition was significantly related to tobacco abstinence (direct effects; Path c); whether condition was significantly related to each mediator (Paths a1 and a2); whether each mediator was significantly related to tobacco abstinence (Paths b1 and b2) controlling for treatment; and whether the prediction of abstinence by condition became non-significant when each mediator was entered separately with condition as a predictor of tobacco abstinence (Path c′).

Figure 2.

Causal Steps mediation test

Next, we tested for simple and multiple mediation using the innovative nonparametric bootstrapping procedure recommended by MacKinnon [29] and further articulated by Preacher and Hayes [30,31] designed to estimate the sampling distribution of the indirect effect. The indirect effect is represented by the product of the coefficients (e.g., a1b1 in Figure 2). This bootstrapping procedure assumes that the distribution of the measured variables approximates that of the population while it avoids making the often-tenuous assumption that the indirect effect is normally distributed. For all analyses tobacco abstinence was coded as 1= abstinent and 0= ST use, and condition was coded as 1= Enhanced Condition and 0= Basic Condition.

RESULTS

Tobacco abstinence

A total of 11.4% (46/402) of participants were tobacco abstinent at both the 3- and 6-month assessments: 16.1% (23/143) in the Enhanced Condition and 8.9% (23/259) in the Basic Condition. Contingency table analysis revealed a significant effect benefiting the Enhanced condition (χ2= 4.72, p= .030, Odds Ratio (OR)= 1.97, 95% Confidence Interval (CI)= 1.06 – 3.65). These results for the subset of 402 participants are consistent with the results reported for the full sample of 2523 (intent-to-treat analysis) reported in the outcome results paper [21].

Changes in putative mediators

The Enhanced Condition showed significantly more improvement in self-efficacy from Baseline to the 6-week follow-up assessment than the Basic condition (M= 0.43 & SD= .98 vs. M= 0.71 & SD= .91; t= −2.85, df= 310.42, p= .005, 2-tailed, assumed unequal variances; d= .30). Similarly, the Enhanced Condition had greater program exposure than the Basic Condition (M= .59 & SD= 1.16 vs. M= −.32 & SD= .50; t= −8.87, df= 171.82, p= .000, 2-tailed, assumed unequal variances; d=1.10).

Simple mediation

We examined each of the putative mediators alone in a test for simple mediation using Baron and Kenny’s [28] causal steps strategy (using paths described in Figure 2). The effect of condition on tobacco abstinence was significant (Path c; β= .108, p= .030). For program exposure, we found significant effects of condition on program exposure (Path a2; β= .477, p= .000) and for exposure on tobacco abstinence (Path b2; β= .133, p= .008). The effect of condition on abstinence was markedly reduced and became statistically nonsignificant when controlled for the effects of program exposure (Path c2′; β= .039, p= .304). For change in self-efficacy, we found significant effects of condition on self-efficacy (Path a1; β = .139, p= .005) and self-efficacy on abstinence (Path b1; β= .051, p= .002). The effect of condition on outcome was markedly reduced and became statistically nonsignificant when controlled for the effects of self-efficacy change (Path c1′; β= .039, p= .304). Thus, self-efficacy and program exposure were both identified as simple mediators.

Next we tested for simple mediation using Preacher and Hayes’ [30,31] bootstrapping methodology for indirect effects based on 5,000 bootstrap resamples to describe the confidence intervals of indirect effects in a manner that makes no assumptions about the distribution of the indirect effects. Interpretation of the bootstrap data is accomplished by determining whether zero is contained within the 95% confidence intervals (thus indicating the lack of significance). Results for simple mediation showed that both change in self-efficacy and program exposure were simple mediators. Thus the causal steps test and the bootstrapping test agreed that self-efficacy and program exposure were simple mediators (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Simple and multiple mediation of the indirect effects of treatment condition on tobacco abstinence (at 3- and 6- month follow-up assessment) through changes in self-efficacy and program exposure (N= 402; 5,000 bootstrap samples)

| Point | BCa ‡ 95% CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | ||

| Simple indirect effects | ||||

| Self-efficacy | .0129 | .0028 | .0318 | |

| Program exposure | .0334 | .0005 | .0800 | |

| Multiple indirect effects | ||||

| Self-efficacy | .0122 | .0024 | .0309 | |

| Program exposure | .0293 | −.0030 | .0777 | |

| TOTAL | .0415 | .0080 | .0896 | |

| Contrast: Self-efficacy vs. Program exposure | −.0171 | −.0666 | .0204 | |

BCa= Bias corrected and accelerated bootstrapping confidence intervals that include corrections for both median bias and skew [43]. Confidence intervals containing zero are interpreted as not significant.

Multiple mediation

Next, we used the nonparametric bootstrapping procedure for multiple mediation which similarly indicated that self-efficacy was a significant mediator of the effect of condition on abstinence (controlling for program exposure) but program exposure was not found to be a significant mediator (controlling for self-efficacy) – its confidence interval contained zero. The contrast testing the two putative mediators was not significant, indicating that the magnitude of these indirect effects could not be distinguished.

DISCUSSION

As successful Web-based tobacco cessation research projects emerge, there is an increasing opportunity to explore possible mechanisms for observed treatment effects. The current paper sought to examine putative mechanisms underlying a successful Web-based smokeless tobacco cessation trial. We examined two putative mediators – self-efficacy change and program exposure – using both simple and multiple mediation analysis techniques. Self-efficacy change emerged as a mediator in all tests which is consistent with the Social Cognitive Theory explanation that behavior change programs – including those delivered via the Web – are effective, at least in part, because they encourage positive changes in participant self-efficacy [4,5,32,33].

Program exposure emerged as a mediator using the causal steps test for simple mediation but it fell out as a mediator when considered in combination with self-efficacy change in a test of multiple mediation. Program exposure is a complicated matter – consider that more is not always better and there is likely to be minimal value derived from using more of an ineffective program – but it continues to have key importance for research on Web-based interventions since it is significantly related to outcome. Future research should explore alternate ways to define program exposure and seek to identify whether some participants benefit from very little exposure whereas others follow a more linear dose-response relationship [34].

Limitations

The current study had some limitations including our use of a restricted sample that satisfied the inclusion criteria for the current analyses. This sample of 402 participants represented 15.9% of the original randomized sample of 2523, a reduction caused largely by our requirements to include self-efficacy data at 6 weeks in addition to tobacco use data for both the 3- and 6-month assessments. Our use of a subset of original participants is predicated on our focus to perform secondary analyses of the data [35] whereas we describe results using the entire sample of participants in our outcome report [21]. Although our sample was sufficiently large to permit mediation analyses [36], it is also important to explore alternative imputation methodologies that increase the number of cases that could be used for mediation analyses.

It is also important to note that we did not collect data on the extent that participants may have used other Web-based programs although we have no reason to assume that any such program use occurred differentially by condition. Another possible limitation is our use of self-reported point prevalence abstinence data for the key measures of tobacco abstinence. Although the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) has acknowledged that biochemical verification may not be appropriate for research of low-intensity, low-demand tobacco cessation interventions [37], it has also recommended that cessation studies use prolonged abstinence measures [38]. Additional threats to the ability of any mediation analysis to identify the “true indirect pathway” [39] must also be acknowledged, including the possibility that: (a) putative mediators may, in fact, be highly correlated proxies of other, unmodeled variables; and (b) measurement reliability across variables might be markedly different.

We were also unable to establish the reliability of our global measure of self-efficacy because it was based on a single item. It is noteworthy, however, that we were able to identify a mediation effect even given the potential attenuation of that effect due to the limited reliability of our measure of risk [28]. Future research should consider including additional items that tap different aspects of self-efficacy [40] (e.g., confidence in being able to avoid relapse when experiencing stress, when using alcohol, in the presence of other chewers). It is also important to acknowledge that other putative underlying mechanisms should be measured and analyzed in future research. For example, additional factors addressed by the Enhanced Condition included use of putative risk/protection mechanisms (e.g., stress management strategies, setting a quit date, telling friends and family, planning for tough situations). In contrast to earlier findings of an RCT that tested self-help methods for ST cessation [41], none of these additional risk/protective mechanisms were found to be significant in the ChewFree study. Future research should also explore the contribution of different putative mechanisms (e.g., exposure to symbolic modeling of content via use of video testimonials, participation in Web forums).

Strengths

Our paper has several noteworthy strengths including our use of precautionary steps to attenuate the possibility that putative mediators might reflect prior behavior change rather than predict that change [24,42]. For example, we limited our analyses to participants who had not yet quit at the 6-week assessment. These considerations resulted in the exclusion of 170 participants who reported that they were tobacco abstinent at the 6-week follow-up (“early quitters”) and who accounted for 65.6% (170/259) of all participants abstinent at both the 3- and 6-month assessments. Without an assessment earlier than 6 weeks we are unable to determine the extent to which these early quitters also experienced an improvement in their self-efficacy or program exposure which was followed by lasting tobacco abstinence. As a second precaution to address the temporal precedence requirement of mediation, we limited our measures of program exposure to reflect website visits that occurred before the date of each participant’s 6-week assessment.

Conclusion

We had hypothesized that being able to stop using tobacco would be related to using a Web-based tobacco cessation intervention that included components based on Social Cognitive Theory (e.g., peer modeling through video testimonials and Web forums) designed to increase self-efficacy. In addition, we expected that a more engaging program would also encourage greater program exposure which, in turn, would lead to improvements in self-efficacy and tobacco abstinence. Our results indicate that program exposure and self-efficacy change do, indeed, act as a simple mediators but results from the multiple mediation test underscored the complexity of the interplay between these two factors. Although the timing of our assessments did not permit us to test with confidence whether program exposure preceded self-efficacy change, it is plausible that program exposure would occur before self-efficacy would improve. However, it also possible that individuals with elevated self-efficacy might be predisposed to remain engaged with an intervention in order to thoroughly review program content. In addition, it is also likely that when efficacious individuals use a carefully tailored Web-based intervention that permits rapid access to program content, they might be very efficient at finding what they need thus resulting in briefer exposure. Any attempt to identify a clear-cut linear chain of underlying mechanisms is difficult when considering the temporal requirements for separating the reciprocal impact of attitude change and behavior change. This is especially true when the essential trial involves participants engaged in a Web-based intervention with relatively few opportunities for assessment. Clearly, much remains in terms of improving our understanding of the mechanisms that help to explain positive findings in research on Web-based behavior change interventions. Our results clearly point to the conclusion that outcome is influenced by both changes in self-efficacy and degree of program exposure. Future research should explore alternate ways to measure program exposure, the extent to which some participants benefit from very little exposure whereas others follow a more linear dose-response relationship [34], and to better understand the interplay between program exposure and participant self-efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to Kristopher J. Preacher, Andrew Hayes, and Edward Lichtenstein for their review of earlier drafts of this report. This work was funded, in part, by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA84225).

References

- 1.Alguacil J, Silverman DT. Smokeless and other noncigarette tobacco use and pancreatic cancer: A case-control study based on direct interviews. Cancer Epidemiol.Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:55–58. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDHHS. Report on Carcinogens (RoC; 11th Edition) U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Toxicology Program; 2005. [accessed 12 January 2007]. Available at: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/eleventh/profiles/s176toba.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Severson HH, Gordon JS, Danaher BG, Akers LA. ChewFree.com: Evaluation of a Web-based cessation program for smokeless tobacco users. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2008;10:381–391. doi: 10.1080/14622200701824984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ.Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brandon TH, Herzog TA, Irvin JE, Gwaltney CJ. Cognitive and social learning models of drug dependence: implications for the assessment of tobacco dependence in adolescents. Addiction. 2004;99(Suppl 1):51–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niaura R. Cognitive social learning and related perspectives on drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95(Suppl 2):S155–S163. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention: Theoretical rationale and overview of the model. In: Marlatt GA, Gordon JR, editors. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford; 1985. pp. 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiffman S, Kassel J, Gwaltney C, McChargue D. Relapse prevention for smoking. In: Marlatt GA, Donovan DM, editors. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 92–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linde JA, Rothman AJ, Baldwin AS, Jeffery RW. The impact of self-efficacy on behavior change and weight change among overweight participants in a weight loss trial. Health Psychol. 2006;25:282–291. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strecher VJ, DeVellis BM, Becker MH, Rosenstock IM. The role of self-efficacy in achieving health behavior change. Health Educ.Q. 1986;13:73–92. doi: 10.1177/109019818601300108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: A randomized trial. Med.Care. 2006;44:964–971. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds KD, Buller DB, Yaroch AL, Maloy JA, Cutter GR. Mediation of a middle school skin cancer prevention program. Health Psychol. 2006;25:616–625. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, McAuley E. Falls self-efficacy as a mediator of fear of falling in an exercise intervention for older adults. J Gerontol.B Psychol Sci.Soc.Sci. 2005;60:34–40. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.p34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon LJ, Bunn JY, Pirie PL, Worden JK, Flynn BS. Self-efficacy and outcome expectations for quitting among adolescent smokers. Addict.Behav. 2006;31:1122–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gwaltney CJ, Shiffman S, Balabanis MH, Paty JA. Dynamic self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: Prediction of smoking lapse and relapse. J.Abnorm.Psychol. 2005;114:661–675. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dijkstra A, Wolde GT. Ongoing interpretations of accomplishments in smoking cessation: Positive and negative self-efficacy interpretations. Addict.Behav. 2005;30:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Moderators and mediators of a Web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program among nicotine patch users. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2006;8:S95–S101. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper ME, Federmen EB, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, et al. Using mediational models to explore the nature of tobacco motivation and tobacco treatment effects. J.Abnorm.Psychol. 2008;117:94–105. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danaher BG, Boles SB, Akers L, Gordon JS, Severson HH. Defining participant exposure measures in Web-based health behavior change programs. J.Med.Internet Res. 2006;8:e15. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.3.e15. http://www.jmir.org/2006/3/e15/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Severson HH, Gordon JS, Danaher BG, Akers LA. ChewFree.com: Evaluation of a Web-based cessation program for smokeless tobacco users. Nicotine Tob.Res. doi: 10.1080/14622200701824984. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon JS, Akers L, Severson HH, Danaher BG, Boles SM. Successful participant recruitment strategies for an online smokeless tobacco cessation program. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2006;8:S35–S41. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. J.Med.Internet Res. 2005;7:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am.J.Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stice E, Presnell K, Gau J, Shaw H. Testing mediators of intervention effects in randomized controlled trials: An evaluation of two eating disorder prevention programs. J.Consult Clin.Psychol. 2007;75:20–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danaher BG, Hart LG, McKay HG, Severson HH. Measuring participant rurality in Web-based interventions. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:228. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J.Pers.Soc.Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacKinnon DP. Contrasts in multiple mediator models. In: Rose J, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. [accessed 21 September 2007];Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. 2007 doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. Manuscript under editorial review; Available at: http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/ahayes/indirect2.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. [accessed 25 September 2007];SPSS and SAS macros for estimating and comparing the effects in multiple mediator models (Indirect.SPS version 3) 2007 Quantpsy.org; Available at: http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/ahayes/SPSS%20programs/indirect.htm.

- 32.Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rimal RN. Closing the knowledge-behavior gap in health promotion: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Health Commun. 2000;12:219–237. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen H, Mackinnon A. The law of attrition revisited. J.Med.Internet Res. 2006;8:e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.3.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fergusson D, Aaron SD, Guyatt G, Hebert P. Post-randomisation exclusions: the intention to treat principle and excluding patients from analysis. BMJ. 2002;325:652–654. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7365.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benowitz NL, Jacob P, Ahijevych K, Jarvis MJ, Hall S, LeHouezec J, et al. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: Issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2003;5:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little TD, Card NA, Bovaird JA, Preacher KJ, Crandall CS. Structural equation modeling of mediation and moderation with contextual factors. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. pp. 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Condiotte MM, Lichtenstein E. Self-efficacy and relapse in smoking cessation programs. J.Consult Clin.Psychol. 1981;49:648–658. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Gordon JS, Barckley MS, Akers L. A self-help cessation program for smokeless tobacco users: Comparison of two interventions. Nicotine Tob.Res. 2000;2:363–370. doi: 10.1080/713688152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu.Rev.Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]