Abstract

The marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii has become a model system for evo-devo, neurobiology and marine biology. The functional assessment of its cell types, however, has so far been very limited. Here we report on the establishment of a generally applicable, cell type specific ablation technique to overcome this restriction. Using a transgenic strain expressing the bacterial enzyme nitroreductase (ntr) under the control of the worm’s r-opsin1 locus, we show that the demarcated photoreceptor cells can be specifically ablated by the addition of the prodrug metronidazole (mtz). TUNEL staining indicates that ntr expressing cells undergo apoptotic cell death. As we used a transgenic strain co-expressing ntr with enhanced green fluorescent protein (egfp) coding sequence, we were able to validate the ablation of photoreceptors not only in fixed tissue, using r-opsin1 riboprobes, but also by monitoring eGFP+ cells in live animals. The specificity of the ablation was demonstrated by the normal presence of the eye pigment cells, as well as of neuronal markers expressed in other cells of the brain, such as phc2, tyrosine hydroxylase and brn1/2/4. Additional analyses of the position of DAPI stained nuclei, the brain’s overall neuronal scaffold, as well as the positions and projections of serotonergic neurons further confirmed that mtz treatment did not induce general abnormalities in the worm’s brain. As the prodrug is administered by adding it to the water, targeted ablation of specific cell types can be achieved throughout the life of the animal. We show that ablation conditions need to be adjusted to the size of the worms, likely due to differences in the penetration of the prodrug, and establish ablation conditions for worms containing 10 to 55 segments. Our results establish mtz/ntr mediated conditional cell ablation as a powerful functional tool in Platynereis.

Introduction

The marine bristle worm Platynereisdumerilii has become a reference system in the fields of evolution and development, as well as in comparative neuroscience. It has retained a more ancestral-type gene repertoire than conventional invertebrate molecular model systems [1], a feature that facilitates its comparison with vertebrates. Studies comparing the bristle worm’s nervous system and the vertebrate forebrain [2], the hypothalamus [3] and eye [4] reveal that key vertebrate brain cell types have correlates in the worm. However, all these comparisons have relied largely on gene expression analyses [5,6]. The functional importance of the respective cell types, however, has so far usually been inferred from other, functionally more established model systems. Although Platynereis cells can be specifically ablated by cold laser nanosurgery [7], this technique still requires manipulation of individual specimens and manual targeting of each cell, and therefore is not easily amenable to higher numbers of cells and worms.

Nitroreductase (ntr)-mediated, spatially and temporally controlled cell ablation, has been pioneered in zebrafish, and since used as a functional tool for the analyses of various tissues, such as pancreatic, heart and germ cells, as well as neuron types [8-10]. For this technique, the coding sequence for the bacterial enzyme Nitroreductase (Ntr), typically fused to a fluorescent protein for visualization, is expressed under the control of a cell type specific enhancer. By electrochemical reduction, Ntr efficiently converts the prodrug metronidazole (mtz) into a highly potent DNA interstrand cross-linking agent, which subsequently causes cell death. In zebrafish, Ntr/mtz-mediated cell death is confined to the ntr expressing cells, whereas the adjacent bystander cells are unaffected [8].

Here we report on the establishment of space and time controlled Ntr-mediated cell ablation in the marine bristle worm Platynereisdumerilii . For establishment, we used a transgenic strain that expresses both egfp and ntr, under the control of the recently described r-opsin1 enhancer specifically in the worm’s r-opsin1+ photoreceptor cells (PRCs) [11]. Administration of mtz to the seawater leads to the specific ablation of all r-opsin1+ photoreceptors, but does not affect directly adjacent cell types, such as the pigment cells of the Platynereis adult eyes or other neuronal cell types in the worms’ brains, including their projections. Using this tool, we were able to ablate the r-opsin1+ photoreceptors from a broad range of stages. Our work establishes the ntr/mtz system as a powerful technique to determine the functional requirement of specific cell types throughout the life of the bristle worm.

Material and Methods

Ethics statement

All animal work was conducted according to Austrian and European guidelines for animal research.

Platynereis culture

Platynereisdumerilii were raised and bred in MFPL marine facility according to established protocols [12].

Generation of r-opsin1::eGFP-F2A-NTR construct

The bacterial nitroreductase was PCR amplified from pNTR-EGFP (gift of Lazaro Centanin from Jochen Wittbrodt’s lab) adding the ribosomal skip site F2A, a stop codon, a BamHI restriction site at 5’ and a XhoI restriction site at 3’ using the following primers:

NTR-F2A-BamHI-fwd: GGATCCGTGAAACAGACTTTGAATTTTGACCTTCTCAAGTTGGCGGGAGACGTGGAGTCCAACCCAGGGCCCAAGCTTATGGATATCATTTCTGTCGCCTT; NTR-Stop-XhoI-rev: GTCACTCGAGGAGCTCCACCGCGGTGACTAGTAGTATCGATACGTCGACTTACACTTCGGTTAAGGTGATGTTTTG

The fragment was cloned into the p3E-EGFPpA vector [13] at the BglII and XhoI sites. The cassette containing eGFP-F2A-NTR was subsequently PCR amplified using primers:

r-opsin1_upperGFPfusion: GAAAGGTCAGCCTTCTGTCGCCTACAACCACCAGCTTACCATGTCTCGGTCAGAGGATCCACCGGTCGCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG

r-opsin1_lowerE2N: GGAAATTTTAAGGTTACATTTCAGCAAATAAGTGGGAAGAAACAAAGCGAAAAGACTTACGGAAAAAACCTCCCACACCTCCCC

and recombined to the first exon of a previously identified BAC containing the r-opsin1 locus [1] using an established protocol for BAC homologous recombination [14]. An 8kbp fragment of the locus was PCR amplified and subcloned into pMosScefrkt318 as described in reference [11] (Figure 1A)

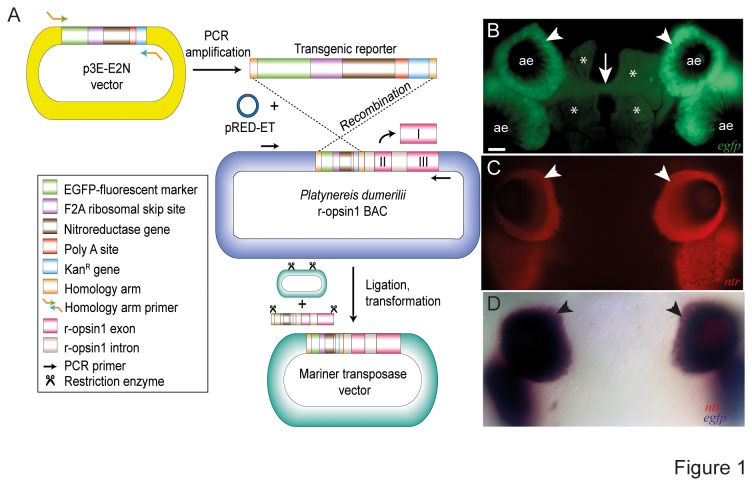

Figure 1. Construction and expression of the r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr transgene.

(A) Schematized generation of the r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr construct. The egfp-f2a-ntr cassette was recombined into the Platynereis r-opsin1 locus by homologous recombination. 8kbps of the surrounding genomic locus plus cassette were PCR amplified and subcloned into the mariner transposon vector used for transgenesis. (B-D) Co-expression of egfp and ntr in the adult eye photoreceptors of r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr stable transgenic worms. (B) eGFP fluorescence demarcating the adult eye photoreceptors and their projections in stable r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr transgenic worms. (C) Expression of nitroreductase (red) in the same cell type as visualized by whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) using nitroreductase antisense riboprobe. (D) Co-staining with nitroreductase (detected in red) and egfp (detected in blue) riboprobes results in purple color, indicative of faithful co-expression of both genes in the adult eye photoreceptors. ae- adult eyes; arrowheads point at expressing cells; arrow points at axonal projection of PRCs; asterisks- head pigment cells which show autofluorescence in the channel used for eGFP documentation. Scale bar: 20µm.

Generation of r-opsin1::eGFP-F2A-NTR transgenic worms

The generation of transgenic worms is described in reference [11].

Whole mount in situ hybridization

Co-localization and levels of ntr and eGFP transcripts in the transgenic animals were detected by using an established double fluorescent whole mount in situ hybridization protocol [11] with minor modifications. In brief: 20-35 segmented premature adult worms of the required genotype/ condition were fixed in 4% PFA/PTW with subsequent methanol washes. Fluorescein-labeled riboprobes were added along with the DIG-labeled riboprobes to the specimens and hybridized overnight at 65°C. Specimens were washed with SSCT at different concentrations, incubated for 1-2hrs in 5% sheep serum/1xPTW followed by incubation with anti-fluorescein-AP Fab fragments (Roche) in a 1:1000 dilution in 2.5% sheep serum/1xPTW for overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, specimens were washed in 1xPTW for 4x15min and equilibrated in 0.1MTris/Hcl (pH 8.2) for 15min. Fast red staining reactions were performed using Fast Red tablets (Roche) dissolved in 0.1M TrisHCl (pH 8.2) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. After staining, specimens were washed twice in 1xPTW to stop staining and incubated in 0.1M glycine/HCl (pH2.2)/0.1% Tween 20 for 30min to inactivate the alkaline phosphatase. After washing 4x in 1xPTW, specimens were blocked for 1h in 5% sheep serum /1xPTW followed by incubation with anti-DIG-AP Fab fragment (Roche) in a 1:2000 dilution in 2.5% sheep serum /1xPTW for overnight at 4°C. Specimens were washed 5x10min in 1xPTW and NBT-BCIP staining was performed.

Metronidazole treatment

Metronidazole (mtz, Sigma, catalog no. M1547) was dissolved in 0.2% DMSO in artificial seawater with vigorous shaking and protected from ambient light. Artificial seawater (ASW) was prepared in accordance with ref [12]. : 10l ASW contained 300 g of Tropic Marine sea salt and 10 ml of each of the following 5 stock solutions. Stock solution 4 should be added after sterilization. Stock solution 1: 2g Na2-EDTA and 20 mg FeCl3 in 100 ml of distilled water. Stock solution 2: 200 mg H3BO4 and 20 mg Na 2MoO 4 in 50 ml of distilled water are added to 50 ml containing 230 mg ZnSO 4, 65 mg MnSO4, 0.6 mg CoSO4, 0.1 mg CuSO 4. Stock solution 3: 2.2 g KBr, 2 mg KI, 0.6 mg LiCl, 6 mg RbCl, 380 mg SrCl2, 3 mg AlCl3 consecutively dissolved in 100 ml of distilled water. Stock solution 4: 10 g NaNO3 and 2 g Na2HPO4 in 100 ml of distilled water. Stock solution 5: 2 g Sodiumsilicate in 100 ml of distilled water

We tested concentrations between 7-25mM mtz. Worms containing 10-20, 25-35 and 45-55 segments were treated with freshly prepared mtz or DMSO control dilutions, respectively, at 18±1°C in the dark for the time indicated. After treatment, the mtz containing or DMSO control medium was replaced by several washes with artificial seawater. Worms were subsequently maintained under normal culture conditions (50% ASW, 50% NSW) [12].

Cryosectioning

Ablated and control adult Platynereis worms (45-55 segmented) were anesthetized in 50:50 7.5M MgCl2: Natural Sea Water (NSW) and subsequently decapitated. The heads were fixed with 4% PFA/PTW for 20min, subsequently incubated in 15% sucrose/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for two hours and in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight at 4°C. We used Tissue-Tek (O.C.T. Compound) to embed the specimens in molds and froze them in dry ice. A MicromHM500 OM Cryostat was used for obtaining 10µm thick sections, which were collected on cryosection-optimized coated glass slides (Superfrost plus, MENZEL-GLASER). The sections were stored immediately at -20°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were re-hydrated for 2x5 min in 1xPTW and immediately blocked in 5% (vol/vol) sheep serum in 1xPTW for 30 min at room temperature. Polyclonal rabbit anti-5-HT serotonin antiserum (1:1000 dilution, Immunostar product No. 20080) and monoclonal mouse anti-acetylated tubulin antibody (1:250 dilution, Sigma Aldrich cat. no. T6793) were diluted in PBS/ 5% sheep serum, and incubated with the sections overnight at 4°C in a wet box covered with parafilm strips. Slides were washed 4x5mins in 1xPTW and further incubated with Cy3-coupled goat anti-rabbit antiserum and Alexa fluor 488-coupled goat anti-mouse antiserum (1:200 dilution, Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. Nuclei were stained by DAPI (1:10000 dilution, Sigma Aldrich). Slides were washed with 1xPTW for 4x5mins and mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen Cat No. P36934).

TUNEL staining

Mtz- and DMSO-treated adult Platynereis (45-55 segmented) worms were anesthetized and decapitated after ~28 hours treatment. The heads were fixed and mounted in Tissue Tek compound as described in the cryosectioning protocol. The TUNEL apoptotic cell death assay was performed by using the In Situ Cell death Detection Kit, TMR Red (Roche Cat No. 12156792910) immediately after sectioning without storage. The sections were fixed with 4% PFA/PBS for 20 min and equilibrated in 1xPBS for 30 min. Slides were incubated in freshly prepared permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% Sodium citrate) for 2 mins on ice. Slides were washed immediately with 1xPBS twice and re-suspended in TUNEL reaction mixture for 60mins at 37°C in a dark, humidified chamber. After reaction, the slides were washed in 1xPBS for 3x5 min and mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen Cat No. P36934).

Microscopy

For live imaging, premature adult worms of the desired genotype were anesthetized in 50:50 mixture of 7.5M MgCl2: natural seawater (NSW) and mounted on glass slides. Worms were covered with the same MgCl2:NSW mixture. Several layers of sticky tape (Tesa) served as spacer to avoid squashing. The eGFP expression in live worms was captured with a Zeiss Axioplan2 microscope.

Head images were taken with a 20x air objective, the tail images with a 40x oil immersion objective. Confocal images for sections were taken using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope with 405, 488 and 561-nm excitation wavelength. Sections were mounted in Prolong Gold antifade reagent. Images were processed using the ImageJ software package (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), to generate maximum intensity z-projections of scans.

Results and Discussion

Nitroreductase and egfp are specifically co-expressed under the r-opsin1 enhancer

We first generated an expression construct that should allow us to both visualize and ablate the cells we aimed to study. For this, we combined egfp and ntr via the ribosomal skip site f2a and placed this expression construct under the control of the already characterized r-opsin1 enhancer ( [11], Figure 1A). Ribosomal skip sites are sequence stretches of viral origin that lead to the generation of separate proteins from a single mRNA [15]. This technique should result in equal amounts of both proteins, while minimizing the risk of mutual functional impairment, as it could arise from fusion proteins [15].

This construct was used to generate a Platynereis transgenic line driving reporter expression in the r-opsin1+ photoreceptors of the worm ( [11], Figure 1B). We next tested if the worms also expressed the coding sequence for ntr, and if this expression was also at similar levels as the egfp expression. For this, we performed whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) using antisense riboprobes against ntr and egfp. As expected, the spatial expression of ntr in transgenic worms was identical to egfp expression in the r-opsin1+ photoreceptors of the worm (Figure 1B-D). Furthermore, both stainings were similarly strong after the same amount of time, suggesting that equal amounts of egfp and ntr are produced, as predicted from the nature of the construct. These data demonstrate that ntr is faithfully co-expressed in the r-opsin1+ photoreceptors, as required for specific ablation of these cells.

Metronidazole addition leads to a loss of fluorescently marked neurons and their projections

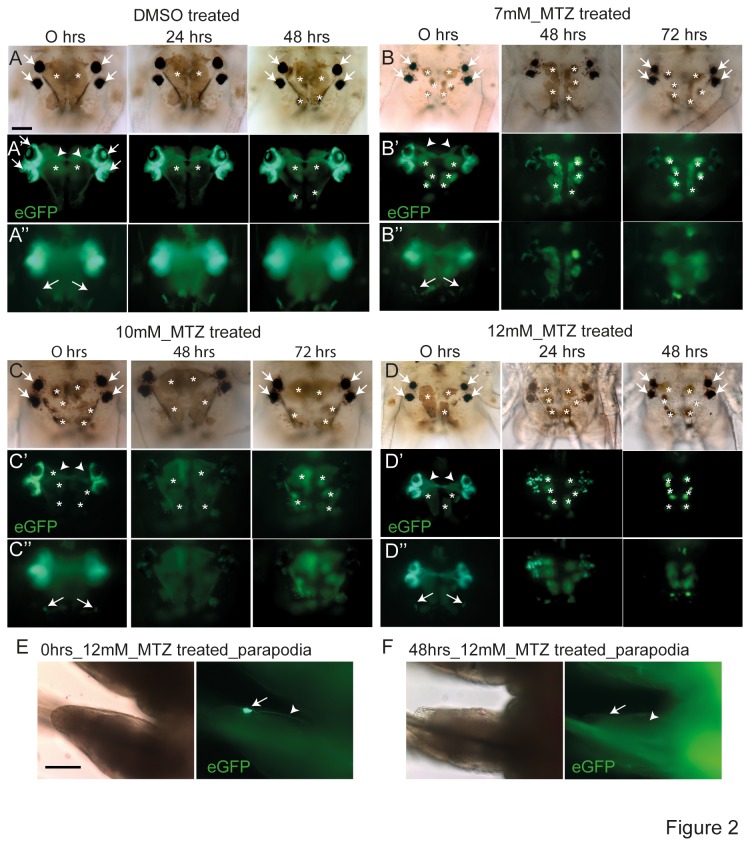

If mtz was able to ablate transgenically labeled cells, we reasoned that exposure to the prodrug would reduce the number of eGFP-fluorescent PRCs in our r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr strain. In a first series of experiments, we therefore incubated 10-20 segmented transgenic worms with three different concentrations of mtz in seawater (7mM, 10mM and 12mM). After 24hrs, 48hrs and 72hrs, we transferred the worms to plain seawater and checked for the pattern and cellular morphology of eGFP+ cells. DMSO-treated control worms never showed any effects on the number and morphology of eGFP- fluorescent cells (Figure 2A-A’’, see Figure 5G,H; S1D for quantification). In contrast, mtz treated animals showed a clear reduction of eGFP-fluorescent cells. After 24hrs, eGFP fluorescent cells in worms incubated with 12mM mtz were severely reduced in numbers (Figure 2D’), no projections of the adult eyes were visible (Figure 2D’) and fluorescence from the region of the lateral frontal eyelets was partly missing (Figure 2D’’). Worms incubated with lower concentrations of mtz (7mM and 10mM), but for extended times (48hrs / 72hrs), exhibited similar partial ablations (Figure 2B-B”, C-C”): Incubation with 7mM mtz for 48hrs or 72hrs led to a significant loss of fluorescent cells in the adult eyes (Figure 2B’), whereas the lateral frontal eyelets were always still visible (Figure 2B”); incubation with 10mM mtz for for 48hrs or 72hrs led to the loss of most fluorescent cells in the adult eyes (Figure 2C’) and of the lateral frontal eyelets (Figure 2C”). As expected, when exposure to the highest dosage (12mM mtz) was also extended to 48hrs, the treated worms lacked all eGFP-fluorescent cells. This included not only the photoreceptors in the head (Figure 2D’,D″), but also the non-cephalic photoreceptors of the trunk (arrows in Figure 2E,F). The neuronal projections of the investigated photoreceptors were absent in worms after any analyzed treatment (arrowheads in Figure 2A’-D’,E, F). Together, these data show that eGFP fluorescence is lost after mtz treatment in a concentration- and incubation time-dependent manner, consistent with the notion that the eGFP+ cells were successfully ablated.

Figure 2. Metronidazole-dependent loss of eGFP fluorescence indicates an effect on r-opsin1+ PRCs in transgenic animals.

All images show live immature adult r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr transgenic animals (10-20 segments). (A-D) Concentration- and incubation time-dependent loss of eGFP fluorescent cells from adult eyes and frontolateral eyelets. Animals were treated with DMSO (A-A”) or varying concentrations of metronidazole (B-B”: 7mM, C-C”: 10mM; D-D”: 12mM). Duration and type of treatment are indicated on top of each panel. Arrowheads point at the axonal projection from the adult eye photoreceptors. Asterisks: head pigment cells that show autofluorescence in the channel used for eGFP documentation. These pigment cells expand or contract depending on light intensity and time of day. Arrows indicate adult eye pigments (panels A-D) position of eGFP-expressing PRCs (panel A’), position of lateral frontal eyelets (A”-D”). (E,F) Loss of eGFP fluorescent non-cephalic PRC upon metronidazole treatment. (E) Parapodium with eGFP-expressing non-cephalic PRC (arrow) and its axonal projection (arrowhead) before metronidazole treatment; (F) same specimen after 48 hrs of exposure to 12mM mtz, with arrow and arrowhead indicating the same positions. Scale bars: 50µm.

While testing different mtz concentrations with worms of different sizes, we noted that the same concentration of mtz can differ in its efficiency depending on the size, i.e. number of segments, of the worm. Worms of the same absolute age can exhibit a range of different sizes, depending on the availability of food and animal density in the box. The size of the worm, best quantified by segment number, but not the absolute age, also determines when a worm will reach maturity [16]. We reasoned that the thickness of the cuticle and body wall will increase with segment number, and hence require a higher concentration of prodrug for penetration. Similarly to the aforementioned studies, we therefore carefully determined the most effective mtz concentrations (leading to the complete absence of GFP+ cells) for worms of different size categories. From these experiments, we suggest the use of the following mtz concentrations:

10-20 segmented worms: 12mM mtz

25-35 segmented worms: 17mM mtz

45-55 segmented worms: 25mM mtz

We also noted that worms homozygous for the transgene tended to respond more efficiently than worms that were only heterozygous, compatible with the possibility that the amount of nitroreductase expressed in the cells is a limiting factor in the ablation procedure. The concentrations we determined here work well for both worms that are homo- or heterozygous for the transgene.

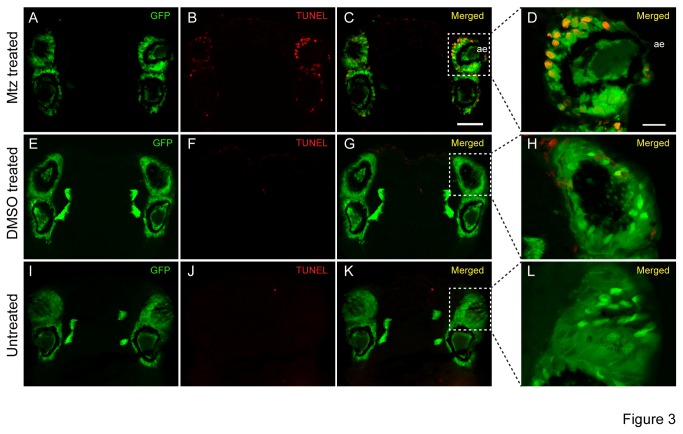

Metronidazole induces apoptosis in nitroreductase expressing cells

To verify that the loss of eGFP fluorescence was a result of the ablation of transgenically labeled cells, and not an effect of mtz on the properties of eGFP, we next tested if the addition of mtz leads to DNA fragmentation and subsequently to induced cell death. The free ends of DNA fragmented in the process of programmed cell death can be detected by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridinetriphosphate nick end-labeling (TUNEL) staining. We therefore established TUNEL detection in premature adult Platynereisdumerilii specimens (45-55 segmented worms). In accordance with the determined optimal concentrations of mtz, we treated worms with 25mM mtz. When analyzed after 28hrs, a well-detectable TUNEL staining was detectable in the areas of eGFP expression, such as the photoreceptors of the adult eyes (Figure 3A-D). Untreated transgenic siblings or addition of DMSO did not show any increase in TUNEL staining over background (Figure 3E-L). These data are in agreement with the idea that ntr-positive cells convert mtz to a cytotoxic compound that then leads to apoptotic death of these cells. Our conditions were highly similar to the treatments used in zebrafish [8,17].

Figure 3. Metronidazole induces apoptosis in transgenically labeled cells.

(A-L) Head sections of mtz treated (A-D), DMSO treated (E-H) and untreated (I-L) premature adult r-opsin1::eGFP-f2A-ntr worms (eye PRCs and projections, green) processed for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridinetriphosphate nick end-labelling (TUNEL) detection (red). (A-D) Apoptosis was detected in PRCs exposed to 25mM mtz after 28 hrs incubation, whereas transgenic animals treated with DMSO alone (E-H) or transgenic untreated animals (I-L), did not show staining above background. ae: adult eye. Scale bars C: 50µm; D: 15µm.

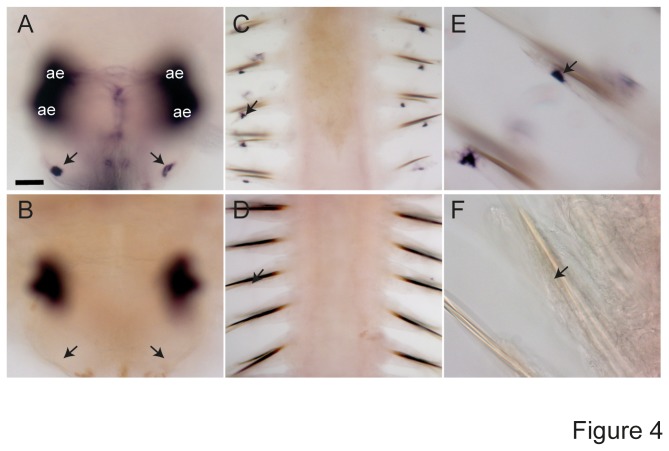

In order to validate that mtz treatment indeed depleted the number of photoreceptors, we performed whole mount in situ hybridization (WMISH) using a riboprobe against Platynereis ropsin1 endogenously expressed in the transgenically labeled cells [11]. Worms with 10-20 segments, incubated in 12mM mtz for 48hrs, showed a complete loss of the WMISH signal at the position of the lateral frontal eyelets in the head (arrows in Figure 4A,B), as well as in the worm’s tail (arrows in Figure 4C-F). As the dark blue NBT/BCIP precipitate is difficult to discriminate from the brown/black eye pigment present in the adult eyes, we used a different detection precipitate (Fast Red) to assess r-opsin1 expression in the adult eyes. No r-opsin1 mRNA can be detected in the adult eyes after mtz treatment (17mM mtz based on segment number) of r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr animals (Figure 5A-F, A’-F’; S1A-C,A’-C’). In contrast, untreated or DMSO-treated transgenic siblings, as well as mtz-treated non-transgenic animals showed no reduction in staining (red staining in Figure 5A-F, A’-F’; S1A-C,A’-C’).

Figure 4. Loss of r-opsin1+ cells by metronidazole treatment.

Whole mount in situ hybridization with a riboprobe specific for Platynereis r-opsin1 on immature adult Platynereis worms (10-20 segments). (A,C,E) DMSO controls, (B,D,F) metronidazole treated worms (12mM, 48hrs). (A,B) Dorsal views on heads (anterior down), focused on the position of the lateral frontal eyelets (arrows). (C-F) Ventral views (anterior down) on immature adult worm tails (C,E) treated with DMSO, (D,F) treated with mtz. Arrows point at the position of the peripheral r-opsin1+ photoreceptor cells. Black ‘needle-like’ structures in C-F are aciculae (bristles). Scale bar: 30µm.

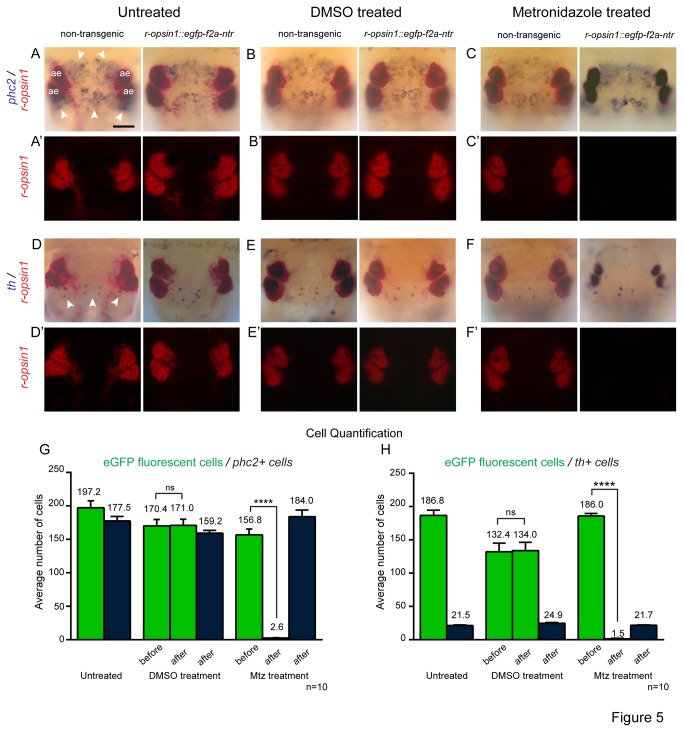

Figure 5. Metronidazole treatment specifically ablates ntr expressing cells, without affecting other brain cells.

(A-F) Metronidazole treatment has no effect on non-PRC marker genes. Comparative analysis of expression patterns of the neuronal marker genes prohormone convertase2/phc2 (arrowheads in A-C) and tyrosine hydroxylase/th (arrowheads in D-F) in untreated (A,A’,D,D’), DMSO treated (B,B’,E,E’) and metronidazole treated (C,C’,F,F’) animals. Each set of panels compares non-transgenic control animals (left) and r-opsin1::eGFP-f2A-ntr transgenic animals. Neuronal marker genes are detected in blue, r-opsin1 were detected with FastRed substrate (red). In panels (A’-F’), FastRed is visualized using fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar: 50µm. (G,H) Quantification of cell numbers in untreated, DMSO treated and mtz treated animals. Individual eGFP fluorescent PRCs (green bars) were counted in live transgenic worms (same animals were counted before and after treatment). phc2 (G) and th (H) expressing cells (black bars) were determined by counting all cells that showed complete cellular outlines in WMISH analyses of animals fixed after the respective experiment. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n=10 worms for each experiment). ****p<0.0001; ns. - no statistically significant differences. The two-tailed paired student t-test was used for statistical analyses.

Taken together, the analyses of two independent markers – eGFP fluorescence and r-opsin1 mRNA expression – along with the presence of a TUNEL signal, provide strong evidence that mtz incubation leads to apoptosis of nitroreductase expressing cells in Platynereis.

Metronidazole-mediated ablation is restricted to nitroreductase expressing cells

In order to assess the specificity of cell ablation in Platynereis, we next investigated if cell ablation was restricted to the ntr expressing cells, or caused more general defects. We tested this by three independent approaches.

First, we focused again on the large adult eyes of Platynereis. In these eyes, r-opsin1+ photoreceptor cells are directly adjacent to pigment cells [18]. If the cell ablation is specific, these directly neighboring pigment cells should remain unaffected. This was indeed observed when we inspected the mtz-treated animals. The pigment cells remained present and were indistinguishable from the pigment cells of all control worms (arrows Figure 2A,B,C,D).

In a second step, we aimed at quantifying the effect of mtz on GFP+ (and hence NTR+) versus GFP- (and hence NTR-) cells. Such quantification is difficult to perform with the pigment cells of the adult eyes, as they are very densely packed and thus difficult to count reliably. Therefore, we performed WMISH with three different genes, whose mRNA is present in cells located in different areas in the head, but not in the ropsin1+ photoreceptors. We visualized the cells expressing Pdu-prohormone convertase 2 (phc2) a prohormone processing enzyme, demarcating neurosecretory cells [3], Pdu-brn1/2/4 a pou-class transcription factor [2], as well as Pdu- tyrosine hydroxylase (th) [2], the enzyme catalyzing L-dopa synthesis [19] with the blue NBT/BCIP precipitate. We also counter-stained for r-opsin1 mRNA in the same animals with the red Fast Red substrate (red in Figure 5A-F,A’-F’, S1A-C,A’-C’). As expected, r-opsin1 was rarely detectable or undetectable in mtz treated animals compared to untreated and DMSO treated controls (Figures 5A’-F’, S1A’-C’). In contrast, phc2, brn1/2/4 and th staining was indistinguishable in mtz treated vs. untreated or DMSO treated animals (blue in Figure 5A-F; S1A-C). This observation was further substantiated by quantification: Whereas there was no significant difference in the number of GFP+ cells in untreated or DMSO treated animals, this number dropped to nearly undetectable in mtz treated animals (green bars in Figure 5G,H; S1D). By comparison, the cell numbers of phc2, brn1/2/4 and th (please note that th+ cells are present at different focal levels) showed no such difference in any of the treatments (black bars in Figure 5G,H;S1D).

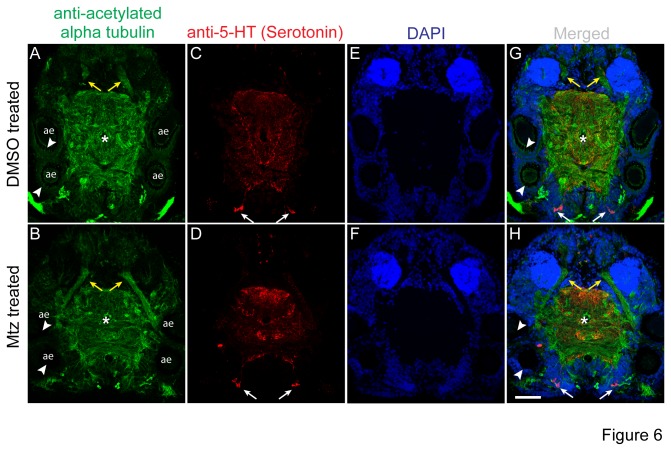

Third, we assessed, if the axonal and dendritic scaffold of the worms is affected by the mtz treatment. Neurite connections are highly stereotypic and have thus been used as alignment grid for the comparison of expression patterns [2-4]. If mtz treatment induced general tissue damage, we reasoned that this should be detectable in disruptions or alterations of the neurite scaffold. In order to test this, we visualized the overall neuronal scaffold using an antibody directed against acetylated tubulin [2-4]. We also used an antibody directed against serotonin, to more specifically investigate a subset of the worm’s axons [3]. Furthermore, we visualized all cell nuclei by DAPI staining, which should reveal any larger aberrations in the brains of mtz treated worms compared to controls. When comparing the overall neurite scaffold (Figure 6A,B,G,H, arrowheads point at the position of GFP expressing PRCs), as well as the axon tracts and cell bodies of serotonergic neurons (Figure 6C,D,G,H) of mtz treated and control worms, we did not observe any general alterations in mtz treated animals indicative of unspecific tissue damage. Similarly, we did not note any difference in overall position of the neuron and glia cells in mtz vs. DMSO treated control worms by the comparison of DAPI stained heads (Figure 6E-H).

Figure 6. Metronidazole treatment does not affect general brain anatomy of Platynereisdumerilii .

Confocal images of 10µm thick horizontal cryosections from premature adult transgenic Platynereis heads (r-opsin1::egfp-f2a-ntr), stained with antibodies against acetylated tubulin (A,B; green), and serotonin (C,D; red), as well as with the DNA-binding agent DAPI (E,F; blue). Panels G and H are merged views of all three channels. Animals (45-55 segments) were treated with DMSO (A,C,E,G) or 25mM metronidazole (B,D,F,H) for ~72-80hrs. No morphological differences were observed in the overall neuropil structure and wiring (B,H, compare to A, G) and the position and wiring of serotonergic neurons (D,H, compare to C, G) in ablated animals compared to controls. asterisks: center of neuropil, arrows: posterior serotonergic neuron cell bodies, yellow arrowheads: antennal nerve, ae: position of adult eyes; white arrowheads: position of GFP+ PRCs in control animals (A,G) and equivalent position in metronidazole-treated animals (B,H) Note absence of eGFP fluorescence in B,H, compared to A ,G, indicative of the successful ablation of the r-opsin1+ PRCs. Scale bar: 50µm; dorsal views, anterior up. Also compare to reference [2] for details of the brain scaffold.

Taken together, these data strongly suggest that NTR/mtz-mediated cell ablations are confined to the cells expressing ntr, and can therefore be used as tool to study specific cell functions in Platynereisdumerilii .

Metronidazole-induced specific cell ablation as tool for cell type analyses in Platynereis dumerilii

Here we report on the establishment of a technique to specifically ablate cell types in the marine bristle worm Platynereisdumerilii . This technique now provides a tool to test the function of cell types that were previously not accessible. As the system is inducible, any given cell type can first function normally during the development of the animals, excluding indirect developmental defects prior to the time of assay. Currently, the major limitation for its use in Platynereisdumerilii is the availability of cell type specific enhancer constructs.

Whereas mtz- mediated cell ablation has been used in well-established molecular model systems, most prominently in zebrafish, with great success, its use in less conventional molecular animal systems – common in the field of evolutionary development – has so far not been explored. We therefore anticipate that this study will also be useful for the establishment of mtz-mediated cell ablation in other model systems. From our establishment of the system in Platynereisdumerilii , we noted two main points that are likely of general relevance for the usage of this technique in other animal systems. First, we noted a dependence of the effectiveness of the treatment on the age (size) of the animals, and likely also on the expression levels of nitroreductase within the targeted cells. This suggests that the exact concentrations and incubation time with mtz should be cross-checked for different animal stages and new expression constructs. Secondly, it has recently been suggested that mtz can induce general DNA damage in Drosophila cells [20]. The respective controls of mtz-treated non-transgenic animals will, of course be required to rule out possible unspecific effects in any phenotypic assay. However, our extensive analyses show that at the used concentrations, mtz neither leads to elevated apoptosis nor to general aberrations in brain morphology, or change in neuronal marker genes expressed outside the ntr expressing cell population. This makes mtz induced ablation of transgenically ntr expressing cells a useful tool to obtain a functional understanding of Platynereisdumerilii cell types.

Supporting Information

Expression of brn1/2/4 in control vs. mtz-treated animals. Related to Figure 5.

(A-C) WMISH of brn1/2/4 (blue), counterstained with r-opsin1 (red), white dotted circle indicates major expression domain of brn1/2/4, used for quantification. (A’-C’) Fluorescent visualization of the Fast Red precipitate, used for r-opsin1 expression detection. Dorsal views, anterior down

Blue staining at the very anterior of the head (out of focus in A) is unspecific background staining caused by probe trapping in gland cells. (D) Quantification of cell numbers in mtz- treated vs. control worms. Green bars: number of GFP+ cells in live animals (same animals were counted before and after treatment). Black bars: number of brn1/2/4 cells in fixed animals (can only be counted once).

Details of treatment conditions and quantification as described for Figure 5. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n=10 for each experiment). ****p<0.0001; ns. - no statistically significant difference. The two-tailed paired Student t-test was used for statistical analyses. Scale bar: 50µm.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Tessmar-Raible and Raible labs for helpful discussions on the experiments and two anonymous referees for the constructive feedback on our work. The ntr coding sequence was a kind gift of Lazaro Centanin in Jochen Wittbrodt’s lab.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a PhD fellowship of the Bohringer Ingelheim Foundation (http://www.bifonds.de/homepage.html) to RMF, funds of the Max F. Perutz Laboratories (http://www.mfpl.ac.at/home.html), the research platform “Marine rhythms of Life” of the University of Vienna, a FWF (http://www.fwf.ac.at/) START award (#AY0041321) and HFSP (http://www.hfsp.org/) research grant (#RGY0082/2010) to KTR. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement 260304 (to FR). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Raible F, Tessmar-Raible K, Osoegawa K, Wincker P, Jubin C et al. (2005) Vertebrate-type intron-rich genes in the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii. Science 310: 1325-1326. doi:10.1126/science.1119089. PubMed: 16311335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomer R, Denes AS, Tessmar-Raible K, Arendt D (2010) Profiling by image registration reveals common origin of annelid mushroom bodies and vertebrate pallium. Cell 142: 800-809. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.043. PubMed: 20813265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tessmar-Raible K, Raible F, Christodoulou F, Guy K, Rembold M et al. (2007) Conserved sensory-neurosecretory cell types in annelid and fish forebrain: insights into hypothalamus evolution. Cell 129: 1389--1400. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.041. PubMed: 17604726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arendt D, Tessmar-Raible K, Snyman H, Dorresteijn AW, Wittbrodt J (2004) Ciliary photoreceptors with a vertebrate-type opsin in an invertebrate brain. Science 306: 869-871. doi:10.1126/science.1099955. PubMed: 15514158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Denes AS, Jékely G, Steinmetz PR, Raible F, Snyman H et al. (2007) Molecular architecture of annelid nerve cord supports common origin of nervous system centralization in bilateria. Cell 129: 277-288. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.040. PubMed: 17448990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dray N, Tessmar-Raible K, Le Gouar M, Vibert L, Christodoulou F et al. (2010) Hedgehog signaling regulates segment formation in the annelid Platynereis . Science 329: 339-342. doi:10.1126/science.1188913. PubMed: 20647470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jékely G, Colombelli J, Hausen H, Guy K, Stelzer E et al. (2008) Mechanism of phototaxis in marine zooplankton. Nature 456: 395-399. doi:10.1038/nature07590. PubMed: 19020621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Curado S, Stainier DY, Anderson RM (2008) Nitroreductase-mediated cell/tissue ablation in zebrafish: a spatially and temporally controlled ablation method with applications in developmental and regeneration studies. Nat Protoc 3: 948-954. doi:10.1038/nprot.2008.58. PubMed: 18536643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White YA, Woods DC, Wood AW (2011) A transgenic zebrafish model of targeted oocyte ablation and de novo oogenesis. Dev Dynam 240: 1929-1937. doi:10.1002/dvdy.22695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernandes AM, Fero K, Arrenberg AB, Bergeron SA, Driever W et al. (2012) Deep brain photoreceptors control light-seeking behavior in zebrafish larvae. Curr Biol 22: 2042-2047. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.08.016. PubMed: 23000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Backfisch B, Veedin Rajan VB, Fischer RM, Lohs C, Arboleda E et al. (2013) Stable transgenesis in the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii sheds new light on photoreceptor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 193-198. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215251110. PubMed: 23284166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hauenschild C, Fischer A (1969) Platynereis dumerilii . Mikroskopische Anatomie, Fortpflanzung, Entwicklung. Großes Zoologisches Praktikum: 10b: 1-54 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwan KM, Fujimoto E, Grabher C, Mangum BD, Hardy ME et al. (2007) The Tol2kit: a multisite gateway-based construction kit for Tol2 transposon transgenesis constructs. Developmental Dynam 236: 3088-3099. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21343. PubMed: 17937395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ejsmont RK, Sarov M, Winkler S, Lipinski KA, Tomancak P (2009) A toolkit for high-throughput, cross-species gene engineering in Drosophila . Nat Methods 6: 435-437. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1334. PubMed: 19465918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang W, Ehrlich I, Wolff SB, Michalski AM, Wölfl S et al. (2009) Faithful expression of multiple proteins via 2A-peptide self-processing: a versatile and reliable method for manipulating brain circuits. J Neurosci 29: 8621-8629. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0359-09.2009. PubMed: 19587267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fischer AH, Henrich T, Arendt D (2010) The normal development of Platynereis dumerilii (Nereididae, Annelida). Front Zool 7: 31. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-7-31. PubMed: 21192805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Curado S, Anderson RM, Jungblut B, Mumm J, Schroeter E et al. (2007) Conditional targeted cell ablation in zebrafish: a new tool for regeneration studies. Developmental Dynamics 236: 1025-1035. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21100. PubMed: 17326133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arendt D, Tessmar K, de Campos-Baptista MI, Dorresteijn A, Wittbrodt J (2002) Development of pigment-cup eyes in the polychaete Platynereis dumerilii and evolutionary conservation of larval eyes in Bilateria. Development 129: 1143-1154. PubMed: 11874910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Michal G (1999) Biochemical Pathways. Heidelberg: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palermo AM, Dolores M (2013) Metronidazole induced DNA damage in somatic cells of Drosophila melanogaster. Current. Drug Saf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of brn1/2/4 in control vs. mtz-treated animals. Related to Figure 5.

(A-C) WMISH of brn1/2/4 (blue), counterstained with r-opsin1 (red), white dotted circle indicates major expression domain of brn1/2/4, used for quantification. (A’-C’) Fluorescent visualization of the Fast Red precipitate, used for r-opsin1 expression detection. Dorsal views, anterior down

Blue staining at the very anterior of the head (out of focus in A) is unspecific background staining caused by probe trapping in gland cells. (D) Quantification of cell numbers in mtz- treated vs. control worms. Green bars: number of GFP+ cells in live animals (same animals were counted before and after treatment). Black bars: number of brn1/2/4 cells in fixed animals (can only be counted once).

Details of treatment conditions and quantification as described for Figure 5. Data represent means ± S.E.M. (n=10 for each experiment). ****p<0.0001; ns. - no statistically significant difference. The two-tailed paired Student t-test was used for statistical analyses. Scale bar: 50µm.

(TIF)