Abstract

Previous research has shown that the development of alcohol and tobacco dependence is linked, and that both are influenced by family environmental and intrapersonal factors, many of which likely interact over the life course. The current study identifies general and substance-specific predictors of comorbid problem behavior, tobacco dependence, and alcohol abuse and dependence. Specifically, we examine the effects of general and alcohol- and tobacco-specific environmental influences in the family of origin (ages 10 – 18) and family of cohabitation (ages 27 – 30) on problem behavior and alcohol- and tobacco-specific outcomes at age 33. General environmental factors include family monitoring, conflict, bonding, and involvement. Alcohol environment includes parental alcohol use, parents’ attitudes toward alcohol, and children’s involvement in family drinking. Tobacco-specific environment is assessed analogously. Additionally, analyses include the effect of childhood behavioral disinhibition and control for demographics and initial behavior problems. Analyses were based on 469 participants drawn from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP) sample. Results indicated that (a) environmental factors within the family of origin and the family of cohabitation are both important predictors of problem behavior at age 33; (b) family of cohabitation influences partially mediate the effects of family of origin environments; (c) considerable continuity exists between adolescent and adult general and tobacco (but not alcohol) environments; age 18 alcohol and tobacco use partially mediates these relationships; and (d) childhood behavioral disinhibition, contributed to age 33 outcomes, over and above the effects of family of cohabitation mediators. Implications for preventive interventions are discussed.

Keywords: family environment, alcohol environment, tobacco environment, behavioral disinhibition, romantic partner, adolescent alcohol and tobacco use, comorbid problem behavior

Along with other risk-taking behaviors, alcohol and tobacco use increases and peaks during adolescence and young adulthood, with 50% of all young adults reporting binge drinking in the past month and over two thirds reporting lifetime smoking (Bachman, et al., 2002; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011; SAMHSA, 2010). The majority of adolescents reduce the frequency of their alcohol use and many quit smoking by their mid-20s when they begin to take on adult roles (Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002; Maggs & Schulenberg, 2004). Consequently, by their 30s, only 40% of Americans report past year tobacco use and a third report past month binge drinking (SAMHSA, 2010). On the other hand, the group of young adults who are chronic or persistent users are of significance in addiction research because this group may have already developed or are at risk for developing abuse and dependence disorders (Chassin, Pitts, et al., 2002; Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996).

Substance abuse and dependence are generally believed to be influenced by a combination of environmental and individual risk factors (Kreek, Nielsen, Butelman, & LaForge, 2005; Rutter, Moffitt, & Caspi, 2006). The same risk factors have also been implicated in other problem behaviors that frequently co-occur with alcohol and tobacco use, such as illicit drug use, risky sex, and criminal activity (Jackson, Sher, & Schulenberg, 2005; McGee & Newcomb, 1992; Young, Rhee, Stallings, Corley, & Hewitt, 2006). Among these risk and protective factors, the effects of family experiences have been particularly well documented (Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Hill, Hawkins, Catalano, Abbott, & Guo, 2005; Hops, Tildesley, Lichtenstein, Ary, & Sherman, 1990). Studies have also found that, as adolescents leave parental homes, families created with romantic partners and spouses (referred to here as family of cohabitation) become increasingly influential. The quality of partnered relationships has been linked to problem behavior, and studies have shown a concordance between cohabitating partners’ level of substance use (for review, see Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). The current study examines the effects of environmental influences in the family of origin and family of cohabitation on the development of alcohol- and tobacco-related problems and other comorbid behaviors such as illicit drug use, sexual risk behavior, and crime.

Predictors of Problem Behavior

Family Environments

Within the family domain, general family functioning and alcohol- and tobacco-specific influences have been identified as important predictors of problem behavior. Moffitt has argued that the strongest predictors of adult deviance can be traced to early childhood (Moffitt, 1993a, 2003), and studies have found that early risk factors in the family, such as parental substance use, low parental monitoring, and family conflict, predict later substance abuse, high-risk sexual behavior, and involvement in crime (e.g., Chassin, Presson, Rose, Sherman, & Prost, 2002; Engels, Vermulst, Dubas, Bot, & Gerris, 2005; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). On the other hand, protective factors such as consistent family management and bonding can act as buffers against risk exposure and are associated with more positive outcomes (Galaif, Stein, Newcomb, & Bernstein, 2001; Guo, Hawkins, Hill, & Abbott, 2001; Ryan, Jorm, & Lubman, 2010).

Family influences remain important contributors to problem behavior throughout development, although the family composition changes as children move away from their parental homes and establish their own families. Relationship quality with an intimate partner and partner’s substance use have been shown to be important predictors of individual’s substance use and other problem behavior (Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010). Positive relationship qualities, such as attachment, involvement, and support, consistently play a protective role against problem behavior (Laub, Nagin, & Sampson, 1998; Simons, Stewart, Gordon, Conger, & Elder, 2002). At the same time, studies routinely find partner intercorrelations of .30 to .40 for alcohol use and smoking (Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). For example, Kuo et al. (2007) found considerable spousal concordance of lifetime smoking (rs = .19–.48) in three generations of Australian adults.

Some researchers have made distinctions between general environmental factors that predict problem behavior in general and those risks that are unique to a specific drug (e.g., Andrews, Hops, & Duncan, 1997; Hill, et al., 2005). In this work, we define general family environment as overall family functioning that is not related to substance use, such as parental monitoring, family conflict, and parental warmth. On the other hand, alcohol family environment or tobacco family environment each refer to influences within the family that are specifically associated with alcohol or tobacco, such as parental use of alcohol or tobacco, attitudes regarding each substance, and access to those substances in the home. A large body of literature has shown that positive general family environment plays a protective role in children’s lives, including lowering the risk of aggression and delinquency (e.g., Loeber & Dishion, 1983; Newcomb & Loeb, 1999). On the other hand, tobacco (Bricker, et al., 2006; Engels, Knibbe, de Vries, Drop, & van Breukelen, 1999) and alcohol (Johnson & Leff, 1999; Merline, Jager, & Schulenberg, 2008) environments have each been shown to be significant risk factors for later tobacco and alcohol dependence, respectively. Bailey and colleagues (Bailey, Hill, Meacham, Young, & Hawkins, 2011) found that general family environment during adolescence was uniquely associated with comorbid problem behavior in young adulthood, but that drug-specific family factors such as parent smoking and drinking were uniquely linked to problematic use of tobacco and alcohol, respectively, and did not predict problem behavior in general.

Developmental Continuity in Family Environment: The Social Development Model

Life-course models in the development of addiction suggest that early family experiences can have a large impact on future behavior, including intergenerational continuity in drug use and other antisocial actions. The theory guiding the present study, the social development model (SDM; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985), explains such continuity in terms of opportunities for involvement, rewards, skills, bonding, and beliefs fostered within the family that set children on either a prosocial or an antisocial path. The SDM has successfully predicted tobacco and alcohol use among adolescents and emerging adults (e.g., Fleming, Kim, Harachi, & Catalano, 2002; Hill, et al., 2005). The SDM also incorporates developmental submodels that specify the different socialization forces and different positive and negative outcomes salient for each developmental stage (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996).

As individuals transition into adulthood and marry or partner, families of origin are joined – and, for many, replaced by – families of cohabitation (Bachman, et al., 2002; Schulenberg, Bryant, & O’Malley, 2004). As children move toward establishing their own families, they are hypothesized to employ the skills and practices they learn in the family of origin in their own families. Romantic partners thus become important sources of influence as the risk and protective factors previously associated with family of origin are then transferred to corresponding risk (e.g., conflict) and protective (e.g., involvement, bonding) factors in the adult family (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Studies examining intergenerational continuity of pro- and antisocial behavior, have found that a positive environment in the family of origin is carried on both through the choice of partner and the subsequent partnered family environment (Fischer, Fitzpatrick, & Cleveland, 2007; Harter, 2000; Leveridge, Stoltenberg, & Beesley, 2005). For example, Donnellan, Larsen-Rife, and Conger (2005) found that youth who experienced positive interactions in the family of origin had more positive and stable romantic relationships later in life.

A number of studies have also examined the apparent continuity in alcohol and tobacco environment that is evident when children of substance abusers partner with substance-abusing others (for review, see Harter, 2000; Johnson & Leff, 1999). This link may be mediated by children’s own substance abuse prior to partnering (e.g., Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2006 & Hawkins, 2006; Latendresse, et al., 2008). The extensive research on children of alcoholics shows that having alcoholic parents is a risk factor for choosing to marry an alcoholic (e.g., Olmsted, Crowell, & Waters, 2003). There is less direct evidence that children of smokers choose smoking partners, yet children of smokers have been shown to associate with smoking peers (e.g., Engels, Vitaro, Den Exter Blokland, de Kemp, & Scholte, 2004) who are likely to make up the social pool from which one’s romantic partner is drawn. Further, the concordance between parent and child smoking (Engels, et al., 2004; Taylor, Conard, O’Byrne, Haddock, & Poston, 2004) and high spousal smoking concordance (Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007) both suggest that such continuity exists.

Individual Vulnerability

Another body of literature has documented the predictive role that individual vulnerabilities play in the development of drug use and other problem behaviors. In particular, a cluster of highly heritable personality traits characterized by sensation seeking, risk taking, and other externalizing behaviors, referred to as behavioral disinhibition (BD; Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999; Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008), has been shown to predict initiating and escalating substance use in adolescence (Brook, Ning, & Brook, 2006; Hill, White, Chung, Hawkins, & Catalano, 2000; Neighbors, Kempton, & Forehand, 1992) and substance abuse and dependence in adulthood (Hu, Davies, & Kandel, 2006; Jackson & Sher, 2005; Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2003).

In addition to being a predictor of alcohol and tobacco use, BD has been linked with other problem behaviors, making it a general rather than a substance-specific vulnerability. Behavioral geneticists have found evidence supporting a genetic liability that is common to both BD and substance abuse (e.g., Button, et al., 2007; Iacono, et al., 1999; Iacono, et al., 2008), suggesting that BD may be an indicator, or endophenotypic marker, of genetic vulnerability to antisocial behavior. This common genetic liability also has been hypothesized to explain the high degree of comorbidity between substance use and other problem behavior, such as involvement in crime and sexual risk taking (McGee & Newcomb, 1992; McGue, Iacono, & Krueger, 2006; Young, et al., 2006). Because of this comorbidity, it is difficult to separate predictors of general externalizing behavior from factors that predict substance-specific addiction (Conway, Compton, & Miller, 2006), making it difficult to establish, for example, whether a particular gene is associated with involvement in many types of problem behavior or with only drug-specific behavior.

Current Study

Although extensive research has focused on environmental risks during adolescence and adulthood, less is known about the relation between adolescent and adult family environments in predicting problem behavior in adulthood. Also, little is known about the ways that family environments interact with individual vulnerabilities, such as behavioral disinhibition. The goal of this study is to build a model of adult comorbid problem behaviors and non-comorbid alcohol and tobacco problems that identifies the paths of family environmental influences and individual characteristics from adolescence to adulthood. We consider family environments as a sequence of shifting contexts from family of origin in adolescence to family of cohabitation in young adulthood, and distinguish general and alcohol- and tobacco-specific family factors as predictors. We also distinguish predictors of comorbid problem behavior, which includes alcohol and tobacco use as well as use of illicit drugs, sexual risk behavior, and criminal acts, from predictors of tobacco and alcohol problems that occur without involvement in other forms of problem behavior. The study is guided by four hypotheses (see Appendix 1):

1. General, and alcohol-specific, and tobacco-specific environmental factors in the family of origin predict age 33 comorbid problem behavior, alcohol abuse and dependence, and tobacco dependence, respectively

Bailey et al. (2011) found that general adolescent family environment predicted age 24 comorbid problem behavior, whereas adolescent family tobacco-specific and alcohol-specific environments predicted age 24 alcohol and tobacco use respectively. We hypothesized that these relationships persist through age 33. In extending the work of Bailey et al., we believe it is important to examine a range of distal outcomes related to social environments to better understand the potentially long-lasting influence that early experiences may have on later problem behavior. Further, we sought to extend the model proposed in the Bailey et al. study to a later age when alcohol and tobacco misuse and other problem behavior is no longer part of a normative trend (Schulenberg & Maggs, 2002), suggesting a risk for persistent tobacco or alcohol addiction.

2. Behavioral disinhibition assessed during adolescence predicts comorbid problem behavior at age 33

We hypothesized that behavioral disinhibition predicts comorbid problem behavior at age 33 but not alcohol- or tobacco-specific outcomes. In this prediction, we relied on previous research by behavioral geneticists that has demonstrated that a heritable latent vulnerability toward general problem behavior is manifested through behavioral disinhibition (e.g., Button, et al., 2007; Iacono, et al., 2008). We also hypothesized that behavioral disinhibition moderates the protective effect of adolescent family environment on comorbid problem behavior at age 33 (Hill, et al., 2010). We included a baseline measure of behavior problems (delinquency at age 10) that we expect to be highly related to behavioral disinhibition because of their underlying common cause. Finally, we hypothesized that early delinquent acts, such as stealing and fighting, might be associated with comorbid behavior problems and criminal behavior in adulthood at age 33.

3. General and alcohol- and tobacco-specific environments in the family of origin (ages 10 – 18) predict general and alcohol- and tobacco-specific environments in the adult family of cohabitation (ages 27 – 30)

Consistent with the life-course view of the social development model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996), we expected to find continuity of environmental influences, such that the general family environment and alcohol- and tobacco-specific family environmental factors in the family of origin are positively associated with their respective family environment counterparts in the family of cohabitation. We hypothesized that skills such as conflict management, which are modeled and learned in the family of origin, are likely to be applied in one’s relationship with a romantic partner. On the other hand, early exposure to alcohol and tobacco use may predispose participants toward choice of an intimate partner who engages in drinking or smoking behavior. We tested whether participants’ alcohol and tobacco use at age 18 mediated these pathways.

4. General and alcohol- and tobacco-specific environments in the family of cohabitation partially mediate the relation between family of origin environments and adult problem behaviors

Following research suggesting lasting effects of both childhood and adult family influences on problem behavior, we hypothesized that adolescent social influences will emerge as distinct predictors from adult factors in predicting age 33 outcomes. We also expected that these influences will persist over and above the association between adolescent substance use and adult substance use problems. Specifically, we hypothesized environmental factors in the family of cohabitation to partially mediate the effect of early family influences, such that family of origin environments would have both direct and indirect effects on age 33 problem behavior. We did not expect to see any change in the effect of behavioral disinhibition on outcomes with the addition of family of cohabitation environmental factors in analyses, because BD has been found to develop early and remain a life-course consistent trait (Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1996; Iacono, et al., 1999; Moffitt, 1993b).

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were drawn from the Seattle Social Development Project, a longitudinal study of 808 youth (412 male) recruited in 1985 from elementary schools serving a mixture of neighborhoods including neighborhoods with high rates of crime (Hawkins, Kosterman, Catalano, Hill, & Abbott, 2005). Almost half of the original sample (46%) came from families with a family income under $20,000 per year, and 52% participated in the National School Lunch/School Breakfast program during at least one year between fifth and seventh grade. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with participants at ages 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 18, and questionnaire data from parents were also collected annually at ages 10 through 16. Follow-up interviews were then administered to participants at ages 21, 24, 27, 30, and 33. From age 11 to 33 annual retention rates averaged 90%, with 92% of the still-living sample having been interviewed at age 33 (deceased n = 23 by age 33). At age 33, 90% of participants participated in face-to-face interviews, 7% completed web surveys, 2% submitted paper surveys, and 1% completed interviews by telephone.

Because a main focus of these analyses was the influence of the family environment (family of cohabitation) in adulthood, we chose to examine family environment at ages 27 and 30, a time when the majority of participants had formed families with live-in spouses or romantic partners. Two time points, ages 27 and 30, were selected to maximize the number of cohabitating participants. Accordingly, participants who did not report a spouse or live-in romantic partner at either age 27 or 30 (n = 311) were excluded from the analyses. Due to their low representation, Native Americans (n = 28) were excluded from these analyses, bringing the final analysis sample to 469 participants. Of these, 237 (51%) were female, 110 (23%) self-identified as African American, 106 (23%) as Asian American, and the majority reported being married during at least one time point (n = 322, 69%).

Throughout the analyses, items in the adolescent subscales were combined and averaged across ages 10 to 18. Measures of family of cohabitation were averaged over ages 27 and 30. Composites were created for cases where at least half of the data points across the waves were present. Items with different response scales were standardized prior to combining. See Appendix 3 for detailed information about the measures.

Measures

Family of origin general family environment (ages 10 – 18)

Family of origin general environment measures included youth report of family management, family conflict, family involvement, and bonding to family members. For all scales, items were recoded as necessary so that higher scores indicate more of the construct (e.g., more bonding, more conflict). Measures were all highly reliable across adolescence: family management average reliability from age 10 to age 18 α = .83, conflict α = .82, positive involvement α = .78, and bonding α = .81. Composite measures were used as indicators of a latent General Family Environment construct (see Appendix 2 for loading coefficients for all latent factors).

Family of origin family alcohol environment (ages 10 – 16)

Family alcohol environment measures included parent drinking, parent drinking attitudes, and involvement of participants in family drinking (e.g., getting or opening a drink for a family member). Adolescent parent drinking (reliability across adolescence α = .89), parent pro-drinking attitudes (reliability across adolescence α = .82), and involvement in family drinking (reliability across adolescence α = .81) measures were used as indicators of a latent alcohol family environment construct.

Family of origin family tobacco environment (ages 10 – 16)

Family of origin smoking environment measures included parent smoking, parent smoking attitudes, and youth involvement in parent smoking (e.g., getting or lighting cigarettes for family members). Preliminary testing indicated a high degree of overlap in parental smoking and drinking attitudes. Accordingly, in the models described below, the residual covariances of these two variables were estimated. Adolescent parent smoking (reliability across adolescence α = .94), parent pro-smoking attitudes (reliability across adolescence α = .80), and involvement (reliability across adolescence α = .61) in family member smoking measures were used as indicators of a family of origin tobacco family environment latent construct.

Delinquent behavior (ages 10–11)

Baseline behavior problems were assessed during the spring and fall of 5th grade when most participants were 10 and 11, respectively. Participants reported whether they had ever engaged in any of eight delinquent behaviors, including hitting a teacher, damaging property, picking fights, and being arrested. Items were assessed either as 1 Yes or 2 No or on a 4-point scale from 1 Never to 4 More than 4 times. Items were recoded such that engaging in any of the behaviors at least once at either time point was recoded as 1 and not engaging coded as 0. Items were summed up for a total Delinquent Behavior score (α =.75).

Behavioral disinhibition (ages 14 – 18)

Disinhibition was measured at ages 14, 15, 16, and 18 by five items that assessed the frequency of risky or impulsive behavior, such as engaging in risk taking on a dare and disregarding consequences. Items were assessed on a 5-point scale anchored at 1 never and 5 2–3 times a month. Items were summed and then averaged across waves creating a single summative score of behavioral disinhibition (reliability across adolescence α =.82).

Alcohol and tobacco use (age 18)

Past month alcohol use (beer, wine, wine coolers, whiskey, gin, or other liquor) was assessed with a single item. Responses were capped at 30. Past month cigarette use was assessed on a 5-point scale anchored at 1 not at all to 5 about a pack a day or more. Responses were recoded to reflect the number of cigarettes per pack (e.g., about half a pack a day was recoded to 10, and about a pack a day or more was recoded to 30).

Family of cohabitation general family environment (ages 27 – 30)

Assessments of family of cohabitation general family environment were collected at two time points when participants were 27 and 30 years old. All items were based upon interactions with a spouse or live-in romantic partner. Family of cohabitation general family environment measures included participant report of conflict with partner, involvement with partner, and partner bonding. Items within subscales were combined to parallel those in the family of origin general environment. Measures of family of cohabitation conflict (α = .83), involvement (α = .77), and bonding (α = .78) were each used as an indicator of a latent general family environment construct (see Appendix 2).

Family of cohabitation partner drinking (ages 27 – 30)

At each point, participants indicated whether a live-in romantic partner or spouse drank alcohol heavily (yes/no). Participants were coded as having a heavily drinking partner if they answered “yes” for at least one of the two time points.

Family of cohabitation partner smoking (ages 27 – 30)

Participants indicated whether a live-in romantic partner or spouse smoked (yes/no). Participants were coded as having a smoking partner if they answered “yes” for at least one of the two time points.

Adult comorbid problem behavior (age 33)

Five adult problem behaviors were measured at age 33: tobacco dependence, alcohol abuse or dependence, other drug abuse or dependence, past-year involvement in crime, and sexual risk behavior. Alcohol abuse or dependence, tobacco dependence, illicit drug abuse, high-risk sexual behavior, and crime were each used as indicators of a latent factor of comorbid problem behavior (see Appendix 2).

Control variables

Key demographic control variables related to behavioral disinhibition, family environment, and adult risk behavior are included here. Gender and ethnicity were self-reported. Childhood socioeconomic status was assessed by eligibility for the National School Lunch/School Breakfast program at any time in Grades 5, 6, or 7, and was taken from school records. Dichotomous variables of gender, African-American ethnicity, Asian American ethnicity, and socioeconomic status were used as controls.

Results

Analyses

All models were estimated using Mplus version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007; Schafer & Graham, 2002). Measures of partner alcohol and tobacco use and the five indicators of the problem behavior latent factor were declared as ordered categorical and the WLSMV estimator was used . The WLSMV estimator applies somewhat more stringent assumptions than FIML, but still uses the full dataset to estimate missing data (see Asparouhov & Muthen, 2010). In the current study, missing data on the outcome variables was 3% for cumulative criminal behavior, 6% for cumulative sexual risk behavior, and 6.2% for the alcohol, tobacco, and drug-related outcomes. Estimation of missing data using WLSMV is appropriate when the amount of missing dependent variable data is not substantial, such as in the current study.

Family of origin general and alcohol- and tobacco-specific environments, family of cohabitation general environment, and comorbid problem behavior were modeled as latent variables (see Appendix 2 for indicator loadings). The χ2 statistic and three indices of model fit (CFI, TLI, and RMSEA) were used to evaluate the model fit throughout. Tables 1 and 2 contain intercorrelations of all modeled variables and descriptive statistics of the dependent variables.

Table 1.

Correlations between model variables (All Participants Who Reported Having a Spouse or Live-in Partner at age 27 – 30)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fam. env. (10–18) | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Alc. env. (10–18) | −.03 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Tob. env. (10–18) | −.02 | .49*** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Beh. disinhibition | −.27*** | .19*** | .19** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Delinquent beh. | −.28*** | .08 | .20*** | .29*** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 6. Fam. env. (27–30) | .33*** | −.08 | −.09 | −.15** | −.18*** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 7. Partner drinks | −.15+ | .16+ | .20* | .13+ | −.02 | −.35*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 8. Alc. use (18) | −.19*** | .13+ | .08 | .25*** | .19*** | −.15*** | −.01 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 9. Cig. use (18) | −.18*** | .04 | .31*** | .24*** | .15*** | −.04 | .00 | .18*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 10. Partner smokes | −.16* | .13+ | .28*** | .21*** | .13* | −.20** | .48*** | .10* | .21*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 11. Alc. diagnosis (33) | −.26** | .18* | .07 | .29*** | .10 | −.22** | .23* | .26*** | .12 | .37*** | 1 | |||||||

| 12. Tob. diagnosis (33) | −.19** | .04 | .33*** | .36*** | .20** | −.18** | .17 | .11 | .38*** | .40*** | .30** | 1 | ||||||

| 13. Drug diagnosis (33) | −.30** | .04 | .07 | .31*** | .21** | −.19* | .28* | .25*** | .08 | .54*** | .66** | .53*** | 1 | |||||

| 14. Crime (33) | −.19** | .13 | .10 | .32*** | .23*** | −.19** | .32*** | .09 | −.04 | .27** | .48*** | .38*** | .65*** | |||||

| 15. Sexual risk (33) | −.25*** | .14* | .25*** | .32*** | .21*** | −.40*** | .36*** | .13* | .09 | .32*** | .52*** | .38*** | .64*** | .40** | 1 | |||

| 16. Gender (male) | −.10* | .07 | .01 | .25*** | .23*** | −.06 | −.14* | .12* | −.01 | −.02 | .32*** | .11 | .13 | .22** | .05 | 1 | ||

| 17. Asian American | −.03 | −.43*** | −.28*** | −.25*** | −.09 | .11* | −.11 | −.13** | −.17+ | −.19** | −.19* | −.32*** | −.30** | −.08 | −.24*** | .00 | 1 | |

| 18. African American | −.03 | −.13* | .03 | .09* | .20*** | −.21*** | −.05 | .10* | −.03 | .07 | .12+ | .12+ | .22** | .14* | .27*** | .03 | −.30*** | 1 |

| 19. SES | −.15** | −.25*** | .13* | −.01 | .20*** | −.07 | −.04 | .05 | .03 | .04 | −.06 | .07 | .02 | .06 | .14** | −.05 | .20*** | .32*** |

Note.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Ethnicity reference group is White.

General Family Environment is coded to reflect general positive family functioning.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable name | Mean (SD) | Range | n(%) reporting >0 behaviors/symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Days in past month drank alcohol (age 18) | 1.95(4.29) | 0–30 | 190(40.5) |

| Cigarettes per day, past month (age 18) | 2.49(6.19) | 0–30 | 117(24.9) |

| Partner drinks heavily | .15(.36) | 0 – 1 | 70(14.9) |

| Partner smokes | .39(.49) | 0 – 1 | 184(39.2) |

| Comorbid problem behavior | |||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence diagnosis | .13(.35) | 0 – 1 | 63(13.4) |

| Tobacco dependence | .18(.38) | 0 – 1 | 78(16.6) |

| Illicit drug abuse or dependence diagnosis | .08(.28) | 0 – 1 | 37(7.9) |

| Crime | .22(.59) | 0 – 4 | 60(12.8) |

| Risky sexual behavior | .40(.66) | 0 – 4 | 171(36.5) |

Modeling problem behavior as a latent variable allowed us to partition variance of the five indicators into shared variance represented by the problem behavior latent factor and nonshared variance unique to each of the individual behaviors (e.g., variance uniquely associated with tobacco dependence). To test the hypotheses regarding the comorbid problem behavior versus the drug-specific effects, we examined associations between predictors and problem behavior as well as between predictors and individual indicators. A path between a predictor and the latent construct thus represents the effect on shared variance in comorbid problem behavior, whereas a path between the same predictor and the residual variance of an indicator represents the effect of the predictor on the nonshared, unique, or specific variance in that indicator. This partitioning of variance yields conclusions regarding the effects of the predictors on comorbid problem behavior versus their effects on specific behaviors. This approach has been used in the past to model deviance (McGee & Newcomb, 1992; Newcomb, et al., 2002).

Two structural equation models were estimated. The first model expanded on the work of Bailey et al. (2011) that linked general and drug-specific family environments to comorbid problem behavior at age 24. We used the same measures of general family adolescent environment as Bailey et al., and the same measure of family smoking and drinking environments with the exception of having excluded sibling smoking and drinking due to low factor loadings. In addition, we used a comparable set of outcome measures as Bailey et al., but now operationalized at age 33. We also expanded the model in two ways. First, we included behavioral disinhibition as a measure of individual vulnerability and tested whether it moderated the relations between family environments and comorbid problem behavior. Second, we controlled for initial behavior problems by adding early delinquency at ages 10–11 into the model.

We first estimated a model that included all of the hypothesized effects (see non-mediated paths in Appendix 1) and competing hypotheses simultaneously. That is, we tested both general and drug-specific effects of family environments on comorbid problem behavior and unique variances of alcohol and tobacco misuse at age 33. We also tested general and drug-specific effects of behavioral disinhibition and early delinquency, and the association between delinquency and unique variance in criminal acts. In order to minimize suppression, at this stage nonsignificant non-hypothesized paths were dropped. The complete set of tested paths, estimates, and confidence interval for all models can be found in Appendix 2. In the second model, we investigated whether family of cohabitation environments during young adulthood mediated the relations between family of origin influences and age 33 outcomes. We also tested age 18 alcohol and tobacco use as potential mediators between adolescent and adult environments.

We used Mplus to explicitly model non-normally distributed outcomes. Measures of problem behavior are non-normative in nonclinical populations and were here modeled as ordered categorical. However, because Mplus does not estimate residual variance of categorical variables, the more traditional approach of regressing residual variance of the indicator on the predictors is not available. Bailey et al. (2011) used phantom latent variables to partition residual variance of the indicators. In this paper, we chose a different approach where the indicators are regressed directly onto the predictors without first formally partitioning residual variance. The two approaches yield identical unstandardized estimates, and we tested both approaches to ensure model integrity. We chose to present standardized estimates from the second approach because of its relative visual simplicity and greater ease of replication for future research.

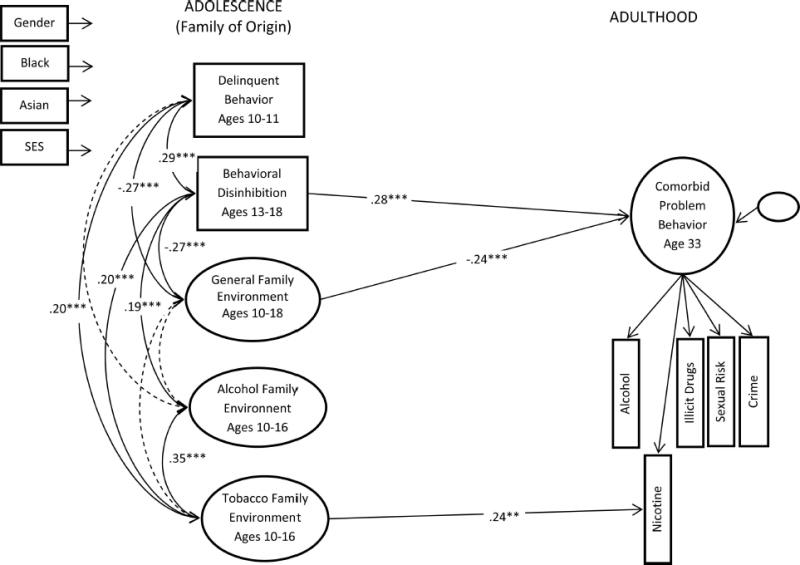

Family of Origin Environments, Behavioral Disinhibition, and Age 33 Outcomes

Our first hypothesis concerned the effect of general and drug-specific family environments in the family of origin on comorbid problem behaviors and drug-specific outcomes at age 33, and our second hypothesis concerned the effect of adolescent behavioral disinhibition on these outcomes. Accordingly, the first model tested these hypotheses by examining the relations between general family environment, alcohol environment, and tobacco environment in the family of origin, and problem behaviors at age 33 (see Figure 1). We tested the hypothesized associations between a) general family environment and comorbid problem behavior at age 33, b) alcohol environment and age 33 alcohol abuse or dependence, and c) tobacco environment and age 33 tobacco dependence. Additionally, we examined the associations between childhood behavioral disinhibition and delinquency and age 33 outcomes. Control variables were allowed to correlate with the predictors, and were set to predict problem behavior. The fit indices showed good model fit: χ2 = 225.06, df = 148, CFI = .95, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .03.

Figure 1.

Estimated model of adolescent environments and age 33 outcomes for participants who reported having a spouse or live-in dating partner at age 27–30 (n = 469), x2(148) = 225.06, comparative fit index = .95, Tucker-Lewis Index = .93, root-mean-square error of approximation = .03. Ethnicity referent is White. General Family Environment is coded to reflect general positive family functioning. All dependent variables are controlled for demographics, which are also correlated with the predictors. SES = socioeconomic status.

** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Consistent with predictions, positive family environment during adolescence had a protective effect, and was negatively associated with comorbid problem behaviors at age 33, but was not uniquely associated with any specific behaviors. Also consistent with our hypotheses, smoking environment in the family of origin was uniquely linked with tobacco dependence in adulthood, suggesting that early exposure to tobacco may predispose children to initiate and maintain smoking into adulthood. However, family of origin alcohol environment was not associated with unique variance of alcohol abuse or dependence at age 33. In support of the second hypothesis, behavioral disinhibition was associated with an increased rate of engaging in comorbid problem behaviors, but not specific problem behaviors at age 33. Consistent with our prediction, there was a moderate association between behavioral disinhibition and delinquent behavior. However, the hypothesized links between early delinquency and comorbid problem behavior or crime were not supported by the results.

The possible interaction between the three adolescent environments and BD was explored using multigroup comparisons. Two groups were created by cutting participants’ behavioral disinhibition scores at the 33rd percentile. Sensitivity analysis changing the cutoff for the high BD group to the 40th percentile yielded similar results. The multigroup comparisons were performed using the DIFFTEST function of Mplus; normal chi-squared difference tests are not appropriate when the WLSMV estimator is used (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007). All factor loadings and structural parameters were constrained to be equal across the two groups in the constrained model. The unconstrained model was then compared to three separate models where the appropriate path between each of the three predictors and the outcome was estimated freely. The DIFFTEST procedure showed no significant interaction between BD and family of origin general environment’s effect on problem behavior (χ2 difference = 2.99, Δdf = 1, p > .05), family of origin alcohol environment’s effect on alcohol abuse or dependence (χ2 difference = 1.15, Δdf = 1, p > .05), or family of origin tobacco environment’s effect on tobacco dependence (χ2 difference = 1.97, Δdf = 1, p > .05). Thus, BD appeared to contribute additively to comorbid problem behavior in adulthood but did not appear to moderate family of origin general environmental influence. That is, a positive family of origin environment had the same inhibiting effect on problem behavior regardless of the degree of participants’ behavioral disinhibition.

Associations between predictor variables (see Table 1) indicate that childhood behavioral disinhibition was associated with less positive home environment and more pronounced alcohol and tobacco environments. Behavioral disinhibition was also associated with delinquent behavior. Delinquent behavior was associated with more prominent tobacco environment and less positive general family environment. Alcohol and tobacco environments were significantly intercorrelated but neither was associated with general home environment. African American children tended to come from families where the alcohol environment was less pronounced. Male gender and identifying as African American were associated with more behavioral disinhibition and delinquent behavior. Being male was also associated with less positive family environments. Asian American children, on the other hand, were less likely to exhibit symptoms of behavioral disinhibition and were also less likely to come from smoking or drinking families. Lower socioeconomic status was associated with less positive family environment and lower family emphasis on alcohol, but a greater presence of nicotine, and greater engagement in delinquent behavior.

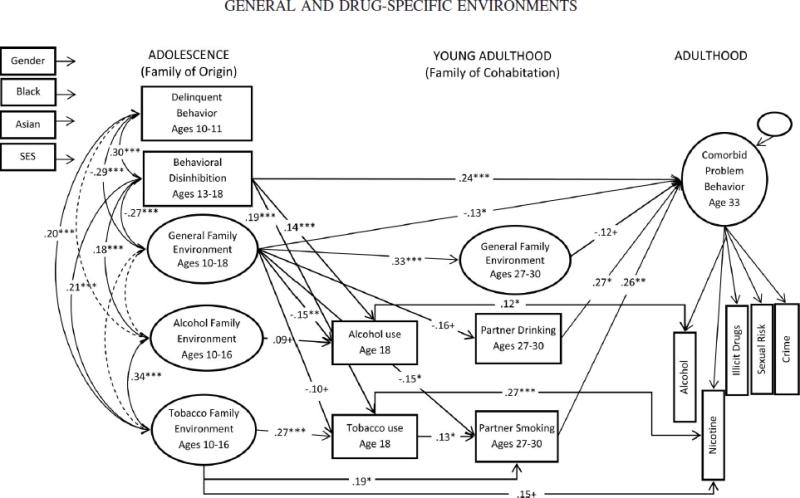

Examining Adult Family of Cohabitation Environments: A Mediational Analysis

Our third and fourth hypotheses considered the effects of environmental influences in the family of cohabitation. We predicted an additive-mediational model where both family of origin and family of cohabitation environments would influence risk behavior, alcohol abuse or dependence, and tobacco dependence. We also tested whether drug-specific adolescent and adult environments were mediated by participants’ substance use in late adolescence (age 18). Retaining all of the paths from Model 1, we added the first block of age 18 alcohol and tobacco use as potential mediators between family of origin and family of cohabitation environments (see Figure 2). Next, the second block of age 27 – 30 romantic partner variables were added as mediators between age 18 substance use and age 33 outcomes. In general, for each dependent variable we tested substance-concordant and general influences of environments (e.g., adolescent alcohol environment to alcohol use at age 18; general family environment to age 18 alcohol use). With respect to the age 33 outcome, we tested the effects of all young adult environmental influences in young adulthood and of family general environment in adolescence (Model 1). Age 18 alcohol and tobacco use were set to mediate all adolescent variables and partner substance use. Each block of the potential mediators was regressed onto the demographic variables, and variables within a block were allowed to intercorrelate. The final model shown in Figure 2 fit the data well: χ2 = 374.98, df = 263, CFI = .95, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .03. As a sensitivity check, associations between age 18 substance use and general outcomes (age 27–30 general family environment and age 33 comorbid problem behavior) were tested separately and found to be nonsignificant. Additionally, we tested whether the marital status of participants at ages 27 and 30 or the presence of children living in the home affected the results. The DIFFTEST procedure in WLSMV estimator showed that neither marital status nor the presence of children moderated findings. These changes were not included in the final model.

Figure 2.

Estimated model of adolescent and adult environments and age 33 outcomes for participants who reported having a spouse or live-in dating partner at age 27–30 (n = 469), x2(263) = 374.98, comparative fit index = .95, Tucker-Lewis Index = .93, root-mean-square error of approximation = .03. Ethnicity referent category is White. General Family Environment is coded to reflect general positive family functioning. All dependent variables are controlled for demographics, which are also correlated with the predictors. Estimated, but now shown in the figure, are the correlations between general family environment in the family of cohabitation (A), partner drinking (B) and partner smoking (C), which were AB = −.35***, AC = −.12+, BC = .46***, and correlation between alcohol and tobacco use at age 18, .12***.

+ p < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

In accordance with our third hypothesis, there was a strong association between general environment in family of origin and general environment in family of cohabitation. Family of origin general environment also had a protective effect on the likelihood of having a substance-using partner in young adulthood. We also found continuity of adolescent tobacco environment and choice of smoking partner, which was partially mediated by age 18 tobacco use. There were no direct effects of adolescent alcohol environment on partner drinking, although continuity from drinking family to alcohol use at 18 was suggested. Unlike tobacco, there was no indication that participants selected partners on the basis of their own alcohol use at age 18.

The fourth hypothesis specified a mediated model where the effects of family of origin environments on age 33 outcomes were predicted to be partially mediated by family of cohabitation variables. As expected, robust associations that indicated continuity from adolescent smoking and drinking to age 33 substance use problems. Consistent with hypotheses, however, after accounting for age 18 substance use and adding the young adulthood variables, a number of direct associations between adolescent predictors and adult outcomes remained significant (see Figure 2). Family of origin general environment continued to play a protective role against engaging in comorbid problem behavior at age 33, indicating a lasting protective effect of positive family functioning during adolescence well into adulthood. A trend toward intergeneration continuity in smoking behavior was indicated by the association between family of origin tobacco environment and greater likelihood of developing tobacco dependence at age 33, over and above initiating smoking by age 18 and having a smoking partner during ages 27 – 30. The effects of behavioral disinhibition on comorbid problem behavior also persisted after the age 18 substance use and partner environments were added to the model.

Similar to family of origin general environment, general environment in the family of cohabitation showed a trending protective effect on comorbid problem behavior at age 33. Having a drinking partner or smoking partner was strongly associated with engaging in comorbid problem behavior, partially mediating the relationship between family environments in adolescence and problem behavior at age 33. However, substance-specific effects of partner drug use were not supported. Next, indirect effects were computed using the bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (BCBOOTSTRAP) (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). There were three significant (p < .05) indirect effects on age 33 tobacco dependence via age 18 smoking: adolescent family environment (probit beta = −.04), behavioral disinhibition (beta = .07) and adolescent smoking environment (beta = .10). Adolescent general family environment had indirect effects on problem behavior at age 33 (beta = −.06) through partner smoking and on alcohol abuse and dependence at 33 (beta = −.03) through partner drinking. Finally, tobacco environment had an indirect effect on comorbid problem behavior through partner smoking (beta = .07).

In regards to demographic controls, results indicated a strong negative relationship between identifying as African American and positive family environment in the family of cohabitation. Compared to women, men were less likely to report a heavily drinking partner. Being male and African American predicted greater comorbid problem behavior at age 33. Regression coefficients and confidence intervals are available in Appendix 2.

Discussion

The conceptual and methodological approaches of this work illustrate three organizing principles for representing the social environment in complex models of addiction. The first principle concerns a clear delineation of a functional domain of influence, such as family, peer, school/work, and neighborhood. The present study focused on the family domain. Second, within each domain, general functioning can be distinguished from the drug-specific aspects of that domain. The current work examines the differential impact of positive general family environment from those influences that are specifically related to tobacco or alcohol. The third principle calls for locating social environment within its developmental context. In the present study, different patterns of prediction emerged for adolescent and adult family environments. The current study is also based upon the organizing heuristic of examining general deviance as measured by comorbid involvement in multiple problem behaviors as compared to involvement only in specific component problem behaviors. Directly modeling the comorbidity between substance use and other externalizing behaviors has allowed us to investigate both general predictors of comorbid problem behaviors and specific predictors of alcohol and tobacco problems that are not comorbid with other problem behaviors.

General vs. Specific Predictors of General vs. Specific Outcomes

Our first major finding concerned identifying environmental factors that uniquely predict alcohol and tobacco problems, over and above their effect on comorbid problem behavior. Results indicate that general family functioning in adolescence predicted comorbid problem behavior at age 33, and that exposure to tobacco in the family of origin was uniquely linked to tobacco dependence in adulthood. These findings are consistent with previous findings by Bailey et al. (2011) on age 24 outcomes. However, the analogous association between adolescent family alcohol environment and later alcohol abuse or dependence at age 33 was not replicated. It is possible that the effect of early alcohol environment is stronger during emerging adulthood but not sustained later in life.

We also examined the effects of behavioral disinhibition as a person-level risk factor previously linked to both adult substance use and problem behavior (Button, et al., 2007; Fu, et al., 2002) and controlled for initial behavioral problems at ages 10–11. We found that behavioral disinhibition had a strong direct effect on comorbid problem behavior above and beyond the impact of environmental factors. Early delinquency and behavioral disinhibition were moderately related, although unlike BD, delinquency did not have an independent effect on comorbid behavior problems. We also investigated whether the adverse effects of BD were moderated by consistently positive family functioning or exacerbated by exposure to alcohol and tobacco influences. None of the interactions between BD and the three family environments emerged as a significant predictor of age 33 outcomes in this study, suggesting that these influences were additive and not multiplicative. It is possible that BD interacts with only certain aspects of the family environment (e.g., consistently poor family management as in Hill et al., 2010) or only during specific sensitive periods in development. Future studies need to continue exploring the potential interactions between environmental influences and behavioral disinhibition and other person-level factors.

General and Drug-Specific Environmental Continuity

The second major finding concerned the environmental continuity of general and drug-specific environments in the family of origin to environments related to cohabiting partnerships in young adulthood. Early general family environmental factors, such as the amount of family conflict and the strength of bonding, appeared to be highly predictive of the quality of romantic relationships in adulthood. This is consistent with the social development model (SDM; Hawkins & Weis, 1985), as well as with findings from literatures on parenting and attachment (e.g., Leveridge, et al., 2005; Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; Shaver & Brennan, 1992). Moreover, a positive general family environment in adolescence was associated with a lesser likelihood of having a smoking and a drinking partner during young adulthood. These effects suggest that practices in the family of origin, such as conflict resolution and child monitoring, have important and long-lasting implications for both general and drug-specific outcomes.

Consistent with prediction, we found continuity from family of origin smoking environment to choosing a smoking partner. This relationship was partially mediated by smoking behavior at age 18, suggesting that children of smokers are more likely to smoke themselves and to choose to partner with a smoker (e.g, Falba & Sindelar, 2008; Kuo, et al., 2007). The direct effect of tobacco environment on choice of partner, however, indicates an additional influence that family of origin on later life choices. For example, children raised in smoking families may become accustomed to the smell of tobacco and its near-constant presence, possibly making the odors familiar and even pleasing in another person (e.g., Etcheverry & Agnew, 2009; Forestell & Mennella, 2005). Continuity in alcohol family environment did not emerge in our analyses, although there was a trend suggesting that presence of alcohol in the family during adolescence increases the likelihood of drinking at age 18. Paired with a nonsignificant connection to age 33 alcohol abuse or dependence, this finding may indicate that adolescent family alcohol environment is a weak predictor of long-term offspring outcomes and choices. It is possible that alcohol use assessed in the current study reflected normative moderate alcohol use and thus was not predictive of offspring problem behavior.

The differential pattern of results for alcohol and tobacco suggests the possibility that parental tobacco use differs from parental drinking in its visibility and accessibility to the child. It may be possible to shield children from parental alcohol use by engaging in drinking late in the evening or only occasionally. Further, although parents’ moderate drinking is not discouraged in society, many parents disapprove of their children’s drinking during childhood and adolescence. Thus, there is an inherent contradiction between some parents’ drinking behavior and their attitudes toward alcohol that may weaken the relation between overall family alcohol environment and children’s alcohol problems. On the other hand, children raised in smoking families who are exposed to tobacco through observation of parental behavior, the smell of cigarettes, and inhalation of secondhand smoke are also less likely to experience parental discouragement from smoking. Because of the highly addictive nature of nicotine and the high stability of smoking behavior in adults (Chassin, Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000), children of smokers are exposed to tobacco throughout the day for many years, have early opportunities to initiate tobacco use themselves and an available supply of the parents’ tobacco products. These patterns of exposure may explain the strong continuity in tobacco-related behavior in our analyses. Finally, it is possible that there are genetic mechanisms unique to nicotine that are transmitted from parents to children, or that secondhand smoke exposure during sensitive periods in early development alters children’s neurochemistry in a way that makes children of smokers more susceptible to later tobacco dependence (Volkow & Li, 2005).

Family of Origin Influences and Family of Cohabitation Mediators

The third set of findings concerned the mediational role that adult environment plays in predicting age 33 outcomes. Our results indicated that both sets of general family environments had an effect on comorbid problem behavior. The long-reaching influence of adolescent family functioning is consistent with Moffit’s (1993a) notion that life-course antisocial tendencies are rooted in genetic and early environmental factors, and that risk-taking trajectories are set early on. The protective effect of positive environment in the family of cohabitation, on the other hand, suggests that targets for preventive interventions extend into adulthood.

With regard to tobacco dependence, we generally found that early family contexts continued to predict tobacco dependence at age 33, even after accounting for smoking behavior at age 18 and having a smoking partner. We did not find a parallel effect for either family of origin or having a drinking partner for alcohol abuse or dependence, over and above age 18 alcohol use. Although substance-specific effects of partner behavior were not evident, both partner smoking and drinking was associated with more comorbid problem behavior, reiterating the notion that both adolescent and young adult environmental influences play an important role in predicting problem behavior.

Finally, consistent with predictions, results indicated that greater childhood behavioral disinhibition increased the risk of engaging in problem behavior at age 33, even after including baseline problem behavior and family of cohabitation environments in the model. Although the links between BD, tobacco, and alcohol problems have been reported in prior studies (Brook, et al., 2006; Hill, et al., 2000), our results suggest that BD plays a greater role in predicting comorbid problem behavior than the unique variance in alcohol or tobacco problems. It is possible that the associations with BD in other studies of tobacco and alcohol addiction emerged as a result of substantial variance that these problems share with problem behavior in general. Partitioning shared variance of comorbid problems from unique variance of tobacco and alcohol problems should help identify drug-specific predictors that can be addressed with drug-specific interventions.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the SSDP sample is a school-based urban sample from the Pacific Northwest. Second, due to the relatively small number of Native Americans in the sample, they were not included in analyses. This is an important demographic group with unique risk factors, and future studies need to closely examine person-environment predictors of tobacco and alcohol addiction in this and other minority populations. Third, drug-specific environments in the family of cohabitation were measured with a single item that may not have captured sufficient variability in partner relationships. Further, although possible effects of marriage status and the presence of children in the home were tested in this study, other family structure variables, such as relationship duration, need to be considered. Studies in this area should also examine partner attitudes and partner-provided opportunities for alcohol use both as they relate to childhood alcohol environment and as predictors of future alcohol dependence. Finally, using a longitudinal design is not sufficient to conclusively determine causation. However, we have included a number of controls in our model that, although not exhaustive, provide a reasonable platform for causal inference (Bullock, Harlow, & Mulaik, 1994).

Conclusions and Implications for Subsequent Research

This study presents an innovative approach to examining person-environment predictors of alcohol and tobacco problems. A major strength of this study lies in the separation of shared variance (comorbid problem behavior) from variance in tobacco and alcohol problems, which helps distinguish causes of general risk-taking behavior from those causes specific to alcohol and tobacco dependence. This approach has important implications for future research, particularly for emerging work in gene-environment interplay in the development of addiction. The current study offers a model for conceptualizing environmental influences suitable for later use in studies of gene-environment interplay that is broad enough to be flexible in multiple research studies yet specific enough to identify targets for preventive intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; R01DA009679; R01DA024411), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; R01AA016960) and by grant 21548 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

The authors gratefully acknowledge SSDP panel participants for their continued contribution to the longitudinal study. We also acknowledge the SDRG Survey Research Division for their hard work maintaining high panel retention, and the SDRG editorial and administrative staff for their editorial and project support.

Contributor Information

Karl G. Hill, Email: khill@uw.edu.

Jennifer A. Bailey, Email: jabailey@uw.edu.

J. David Hawkins, Email: jdh@uw.edu.

References

- Andrews JA, Hops H, Duncan SC. Adolescent modeling of parent substance use: The moderating effect of the relationship with the parent. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:259–270. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.11.3.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthen B. Weighted least squares estimation with missing data. Technical report. 2010 Retrieved February 12, 2012, from http://www.statmodel.com/download/GstrucMissingRevision.pdf.

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Bryant AL, Merline AC. The decline of substance use in young adulthood: Changes in social activities, roles, and beliefs. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Meacham MC, Young SE, Hawkins JD. Strategies for characterizing complex phenotypes and environments: General and specific family environmental predictors of young adult tobacco dependence, alcohol use disorder, and co-occurring problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Andersen M, Leroux BG, Rajan K, Sarason IG. Close friends’, parents’, and older siblings’ smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children’s smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Ning Y, Brook DW. Personality risk factors associated with trajectories of tobacco use. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:426–433. doi: 10.1080/10550490600996363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock HE, Harlow LL, Mulaik SA. Causation issues in structural equation modeling research. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1994;1:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Button TMM, Rhee SH, Hewitt JK, Young SE, Corley RP, Stallings MC. The role of conduct disorder in explaining the comorbidity between alcohol and illicit drug dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Prost J. Binge drinking trajectories from adolescence to emerging adulthood in a high-risk sample: Predictors and substance abuse outcomes. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:67–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.70.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson C, Rose J, Sherman SJ, Prost J. Parental smoking cessation and adolescent smoking. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:485–496. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Pitts SC, Sherman SJ. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: Multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger RC, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Type I and Type II alcoholism: An update. Alcohol Health and Research World. 1996;20:18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway KP, Compton WM, Miller PM. Novel approaches to phenotyping drug abuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:923–928. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(06)00146-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD. Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:562–576. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Knibbe RA, de Vries H, Drop MJ, van Breukelen GJP. Influences of parental and best friends’ smoking and drinking on adolescent use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29:337–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb01390.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Vermulst AA, Dubas JS, Bot SM, Gerris J. Long-term effects of family functioning and child characteristics on problem drinking in young adulthood. European Addiction Research. 2005;11:32–37. doi: 10.1159/000081414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RCME, Vitaro F, Den Exter Blokland E, de Kemp R, Scholte RHJ. Influence and selection processes in friendships and adolescent smoking behaviour: The role of parental smoking. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:531–544. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry PE, Agnew CR. Similarity in cigarette smoking attracts: A prospective study of romantic partner selection by own smoking and smoker prototypes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:632–643. doi: 10.1037/a0017370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falba TA, Sindelar JL. Spousal concordance in health behavior change. Health Services Research. 2008;43:96–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland HH. Linking family functioning to dating relationship quality via novelty-seeking and harm-avoidance personality pathways. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:575–590. doi: 10.1177/0265407507079257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Kim H, Harachi TW, Catalano RF. Family processes for children in early elementary school as predictors of smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:184–189. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Catalano RF. Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:153–167. doi: 10.1177/0272431607313589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestell CA, Mennella JA. Children’s hedonic judgments of cigarette smoke odor: Effects of parental smoking and maternal mood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:423–432. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson E, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, et al. Shared genetic risk of major depression, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence: contribution of antisocial personality disorder in men. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1125–1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaif ER, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Bernstein DP. Gender differences in the prediction of problem alcohol use in adulthood: Exploring the influence of family factors and childhood maltreatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:486–493. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:754–762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter SL. Psychosocial adjustment of adult children of alcoholics: A review of the recent empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:311–337. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance-abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Promoting positive adult functioning through social development intervention in childhood: Long-term effects from the Seattle Social Development Project. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:25–31. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Bailey JA, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Shapiro V. Person-environment interaction in the prediction of alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence in adulthood. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, White HR, Chung I-J, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:892–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Tildesley E, Lichtenstein E, Ary D, Sherman L. Parent-adolescent problem-solving interactions and drug use. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1990;16:239–258. doi: 10.3109/00952999009001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M-C, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development & Psychopathology. 1999;11:869–900. doi: 10.1017/S0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:325–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Similarities and differences of longitudinal phenotypes across alternate indices of alcohol involvement: A methodologic comparison of trajectory approaches. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:339–351. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult alcohol and tobacco use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:612–626. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Leff M. Children of substance abusers: Overview of research findings. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010. Volume I: Secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, Butelman ER, LaForge KS. Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8:1450–1457. doi: 10.1038/nn1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo P-H, Wood P, Morley KI, Madden P, Martin NG, Heath AC. Cohort trends in prevalence and spousal concordance for smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse SJ, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents’ and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub JH, Nagin DS, Sampson RJ. Trajectories of change in criminal offending: Good marriages and the desistance process. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:225–238. doi: 10.2307/2657324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leveridge M, Stoltenberg C, Beesley D. Relationship of attachment style to personality factors and family interaction patterns. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2005;27:577–597. doi: 10.1007/s10591-005-8243-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber RT, Dishion T. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;93:68–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg JE. Trajectories of alcohol use during the transition to adulthood. Alcohol Research & Health. 2004;28:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- McGee L, Newcomb MD. General deviance syndrome: Expanded hierarchical evaluations at four ages from early adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:766–776. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger R. The association of early adolescent problem behavior and adult psychopathology: a multivariate behavioral genetic perspective. Behavior Genetics. 2006;36:591–602. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: Stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction. 2008;103:84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Kessler RC, Shaver PR. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1092–1106. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993a;100:674–701. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.100.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder. Development & Psychopathology. 1993b;5:135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: A 10-year research review and a research agenda; pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors B, Kempton T, Forehand R. Co-occurrence of substance abuse with conduct, anxiety, and depression disorders in juvenile delinquents. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90043-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Battin-Pearson S, Hill K. Mediational and deviance theories of late high school failure: Process roles of structural strains, academic competence, and general versus specific problem behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:172–186. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.49.2.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Loeb TB. Poor parenting as an adult problem behavior: General deviance, deviant attitudes, inadequate family support and bonding, or just bad parents? Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:175–193. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.13.2.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted ME, Crowell JA, Waters E. Assortative mating among adult children of alcoholics and alcoholics. Family Relations. 2003;52:64–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, McMahon RJ. Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:53–100. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:226–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44:774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2009 and 2010. 2010 Retrieved Feb. 16, 2010, from http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2K8NSDUH/tabs/INDEX.PDF.

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Bryant AL, O’Malley PM. Taking hold of some kind of life: How developmental tasks relate to trajectories of well-being during the transition to adulthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:1119–1140. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404040167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]