Abstract

Ghrelin is a 28-amino-acid peptide that plays multiple roles in humans and other mammals. The functions of ghrelin include food intake regulation, gastrointestinal (GI) motility, and acid secretion by the GI tract. Many GI disorders involving infection, inflammation, and malignancy are also correlated with altered ghrelin production and secretion. Although suppressed ghrelin responses have already been observed in various GI disorders, such as chronic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and cachexia, elevated ghrelin responses have also been reported in celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Moreover, we recently reported that decreased fasting and postprandial ghrelin levels were observed in female patients with functional dyspepsia compared with healthy subjects. These alterations of ghrelin responses were significantly correlated with meal-related symptoms (bloating and early satiation) in female functional dyspepsia patients. We therefore support the notion that abnormal ghrelin responses may play important roles in various GI disorders. Furthermore, human clinical trials and animal studies involving the administration of ghrelin or its receptor agonists have shown promising improvements in gastroparesis, anorexia, and cancer. This review summarizes the impact of ghrelin, its family of peptides, and its receptors on GI diseases and proposes ghrelin modulation as a potential therapy.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal tract; Ghrelin; Receptors, ghrelin; Ghrelin O-acyltransferase

INTRODUCTION

In the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, appetite regulation is mainly controlled by multiple anorectic hormones (e.g., cholecystokinin, peptide YY, and glucagon-like peptide-1) and orexigenic hormone (ghrelin) in the gut. Previous review by De Silva and Bloom1 discussed the possibilities of two anorectic gut hormones peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide-1, released after meal as mediation of postprandial satiation, as potential therapeutic targets in obesity. In this review, we will focus on the role of ghrelin in GI diseases, the only identified orexigenic gut hormone so far.

The discovery of ghrelin has enriched our knowledge of the interaction between the GI tract and the brain. This discovery has shed new light on multiple physiologic functions including GI activity, glucose metabolism, insulin release, cardiovascular activity, regulation of pituitary hormone secretion, food intake, and energy homeostasis.

Ghrelin was first discovered in 1999 as a 28-amino acid acylated peptide endogenous ligand of growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHS-R) with a unique posttranslational modification of the Ser3 residue.2 This modification is essential for ghrelin activity. The amino-terminal 10 amino acids of ghrelin are highly conserved among mammals and suggested to have an important role in the protein's activity.3 It is produced by A-like cells and localizes mainly to the oxyntic mucosa of the stomach. Total gastrectomy reduced the plasma concentration by 65% which is produced by the small and large intestine and pancreas.4

Ghrelin is actively involved in multiple physiological functions such as the regulation of growth hormone (GH) secretion,5 adiposity,6 gastric acid secretion,7 and gut motility.8 Ghrelin plays an important role in orexic behaviors on appetite stimulation and regulation of body weight.9 Ghrelin expression in the stomach rises during fasting10 and decreases within 1 hour of having a meal.11 Postprandially, the decrease of plasma ghrelin levels is also proportional to the ingested calorie intake,12 therefore underlining its role as a hunger signal. Ghrelin levels and hunger scores have been shown to be correlated.13 Ghrelin is also associated with the interdigestive contractions of the stomach in rats and stimulation of gastric acid secretion and gastric motility.7,14

Age, lactation, and sex hormones can also influence ghrelin secretion and mRNA expression of octanoylating enzyme ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT), which has a critical effect on ghrelin activity.15 Studies have shown that ghrelin secretion is up-regulated in patients with anorexia16 and cachexia,17 and down-regulated in patients with hyperphagia and obesity.18 Moreover, we recently reported that decreased basal and postprandial ghrelin levels were observed in age-matched female patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) compared to healthy controls. Suppressed ghrelin responses were significantly correlated with meal-related symptoms with higher bloating and satiety rating experienced by female FD patients.19 Our findings also revealed abnormal ghrelin responses in functional GI disorders. However, the mechanisms by which it is regulated in these conditions remain unclear.

GHRELIN-FAMILY PEPTIDES AND RECEPTORS

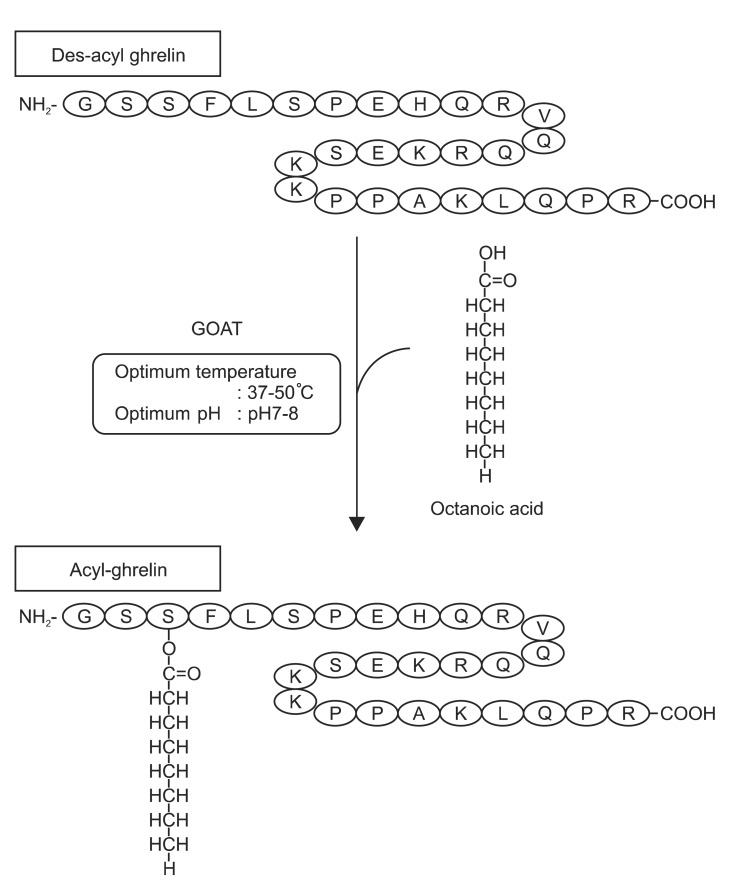

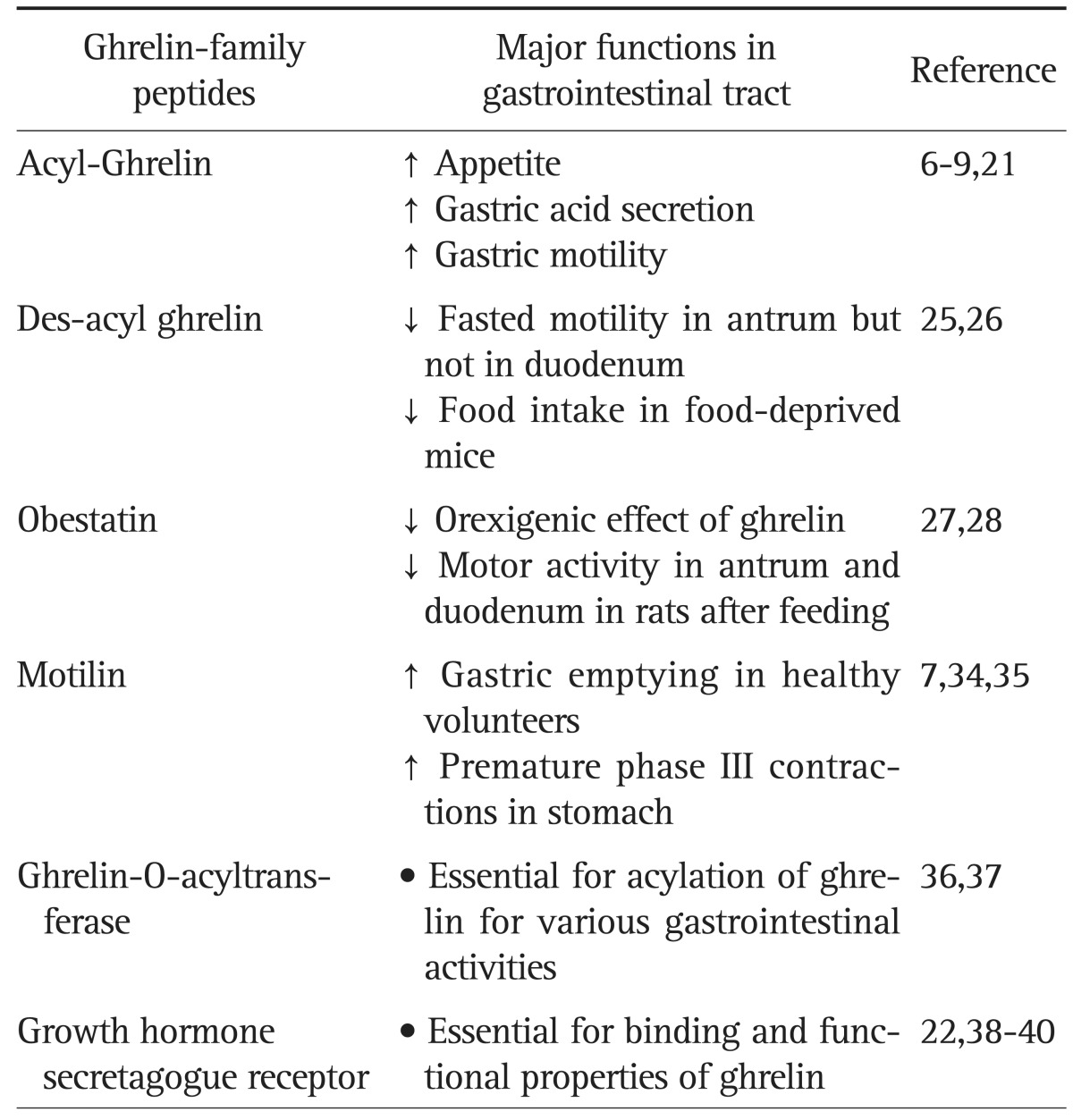

Various derivatives of ghrelin also have crucial roles in the body. Table 1 summarizes the major GI functions of the family of ghrelin-derived peptides. Fig. 1 depicts the relationship between des-acyl ghrelin, GOAT, and acyl-ghrelin.3

Table 1.

Major Gastrointestinal Functions of Ghrelin-Family Peptides and Receptors

Fig. 1.

Structure of human ghrelin and the modification process of octanoic acid by ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT). Adopted from Sato et al. J Biochem 2012;151:119-128, with permission from Oxford University Press.3

1. Acyl-ghrelin

The ghrelin precursor, preproghrelin, is 117 amino acids in length and cleaved to produce the 28-amino acid ghrelin peptide. With alternative splicing, preproghrelin gives rise to a second form of ghrelin, 27 amino acid des-Gln14 ghrelin. Except for the deletion of Gln14, des-Gln14-ghrelin is identical to ghrelin and so retains the n-octanoic acid modification and has the same potency and activities as ghrelin. However the level of des-Gln14 ghrelin in the stomach is low.20 Acyl-ghrelin is responsible for ghrelin's major functions. Acyl-ghrelin requires a medium-chain fatty acid (n-octanoic acid) at the Ser3 residue for complementary binding to the GHS-R type 1a (GHS-R1a).21 The acyl modification of ghrelin is easily cleaved during sample extraction. However, acyl-ghrelin can be isolated from blood specimens by adding ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid with aprotinin or p-hydroxymecuribenzoic acid, separating the plasma by centrifugation and immediate acidification before freezing at -80℃ to ensure stability of acyl-ghrelin during storage.

2. Des-acyl ghrelin

The nonacylated form of ghrelin without octanoic acid modification at Ser3 residue, des-acyl ghrelin is also present at significant level in both stomach and blood.20,22 Des-acyl ghrelin is the most abundant ghrelin-related molecule in the body, comprising 80% to 90% of the total circulating ghrelin, and has a longer half-life. Des-acyl ghrelin was first identified as the inactive form of ghrelin unable to bind to GHS-R. However, des-acyl ghrelin was later proposed to have nonendocrine functions including cardioprotective, antiproliferative, and adipogenic activities, and antagonizing octanoyl-ghrelin-induced effects on insulin secretion and blood glucose levels in humans.23,24 Des-acyl ghrelin was found to disrupt fasting-induced motility in the antrum25 and oppose acyl-ghrelin-induced hyperphagic effects.26

3. Obestatin

Obestatin is a 23-amino acid ghrelin-related peptide encoded by the same gene that encodes ghrelin. Preproghrelin breaks into two peptides, ghrelin, and obestatin.27 With peripheral and central administration, obestatin was found to antagonize ghrelin's effects on food intake, body weight, and gastric emptying, but not on GH levels.28 Studies on obestatin/ghrelin ratio in the GI tract and plasma have been reported to be associated with some disease such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), obesity, and type II diabetes mellitus.29-31

4. Motilin

Significant homology also exists between ghrelin and motilin, which share eight identical amino acids. Similar functions between ghrelin and motilin were proposed due to their structure similarities. Motilin is a 22-amino acid peptide first isolated from the porcine intestine.32 It was further discovered to be predominantly expressed by the endocrine cells of the duodenal mucosa.33 Its concentration decreases distally in the small intestine. Motilin is also present in the thyroid and brain. In addition, ghrelin and motilin both stimulate gastric acid production and gastric movement.7 Motilin inhibits the emptying of a liquid meal34 but accelerates gastric emptying of standard breakfasts and oral glucose solutions, except for fatty cream.35

5. GOAT

The recently discovered enzyme GOAT octanoylates the peptide hormone ghrelin into the acyl-ghrelin peptide, confirmed by gene silencing of GOAT showing reduction of acyl-ghrelin production. GOAT is expressed in the stomach and pancreas. It was proposed that acylated ghrelin may mediate insulin regulation.36 Zhao et al.37 showed that GOAT is essential for ghrelin-mediated elevation of GH, necessary to prevent death from severe calorie restriction through preservation of blood glucose levels. New discovery of GOAT provided new understandings to the ghrelin modulation. Moreover, it also enables a new pathway of therapeutic development in altering ghrelin responses.

6. GHS-R

GHS-R was a G-protein coupled receptors that is expressed in pituitary, hypothalamus, and hippocampus.38 In 1999, ghrelin was identified as the endogenous ligand of GHS-R.21 There are two genes encoded in GHS-R. The first, GHS-R1a, encodes the seven transmembrane domains with binding and functional properties. The other GHS-R type 1b (GHS-R1b), is produced by alternative splicing. It is C-terminal (COOH) truncated from GHS-R1a and it is physiologically inactive.13,38

In the study by Sun et al.,39 mice lacking growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR) showed failure to induce food intake by ghrelin treatment. Body weights of these mice were modestly lower than the wild type controls. Insulin-like growth factor 1 levels were also suppressed despite no difference of food intake was observed.39 Others reported that mice lacking ghrelin receptors also resisted the development of diet-induced obesity. Ghrelin administration failed to stimulate appetite in these mice and they eat less food and store less of their consumed calories. In particular, female mice showed less body weight and adiposity.40 These important findings suggested the lack of ghrelin receptors may alter major physiological functions of ghrelin therefore subsequently influence the GI functions such as appetite stimulation and energy homeostasis.

GHRELIN AND GASTRIC DISORDERS

1. Gastritis

Chronic gastritis is characterized by chronic inflammatory changes in the gastric mucosa leading to extensive mucosal damage and eventual epithelial metaplasia. Destruction of oxyntic mucosa results in loss of gastric intrinsic factor-producing parietal cells, leading to pernicious anemia. Decreased serum ghrelin levels was found to be a sensitive marker of gastric atrophy regardless of Helicobacter pylori infection.41

2. H. pylori infection

H. pylori infection may result in gastritis, increased risk of peptic ulcers42 and gastric carcinoma.43 H. pylori-infected patients were shown to have lower gastric ghrelin mRNA expression than uninfected subjects.44 Furthermore, the suppression of ghrelin mRNA expression is correlated with severity of glandular atrophy and chronic inflammation in the gastric corpus. Plasma ghrelin levels also decrease in H. pylori-infected patients.45 After H. pylori eradication treatment, plasma ghrelin, and gastric preproghrelin mRNA levels increase.46

GHRELIN AND GI TRACT CANCER

Ghrelin expression was detected in many gastric carcinoids, even intestinal neuroendocrine tumors47 and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.48 Significant reduction of ghrelin mRNA and peptide expression in esophagogastric adenocarcinomas compared to adjacent nonneoplastic gastric mucosa was found. This finding suggested that ghrelin production may be suppressed due to damage to normal ghrelin-secreting mucosa from adenocarcinoma.49

In contrast, Huang et al.50 reported that there was no significant difference in plasma ghrelin levels among patients with gastric or colorectal cancer and control subjects. Ghrelin levels in gastric cancer tissues were found to be significantly lower compared to normal tissue in patients with gastric cancer who had had radical subtotal or total gastrectomies. An et al.51 also reported that lower ghrelin levels were present in differentiated tumor tissue than in undifferentiated tissue. These findings suggested that the development of cancer may lead to an inability to produce ghrelin, which is also influenced by the state of differentiation.

In colorectal cancer studies, Waseem et al.52 showed that colorectal cancer cells excessively secrete ghrelin in vitro to promote proliferation. Malignant colorectal tissue samples also showed enhanced stage-dependent expression of ghrelin. However, expression of ghrelin and its functional receptor (GHS-R1a) were suppressed in advanced grade, poorly differentiated tumors. GHS-R1a expression was lost in malignant colorectal cells, while GHS-R1b expression was enhanced.52 Furthermore, this observation was abrogated by pretreatment of a GHS-R1a antagonist or ghrelin-neutralizing antibody.52 The altered expression in GHS-R1b in these tumors was proposed to stimulate proliferative and invading/migrating action even in the absence of growth factors.52

GHRELIN IN FUNCTIONAL GI DISORDERS

1. Gastroparesis

Delayed gastric emptying is caused by gastric motility dysfunction that results in prolonged food retention in the stomach. Delayed gastric emptying is correlated with fullness, nausea, vomiting, impaired fundic accommodation with early satiety, weight loss, and pain. Animal studies have shown that ghrelin enhances GI motility and gastric emptying.53,54 A study by Edholm et al.53 showed that ghrelin stimulates motility in vitro and that ghrelin receptors are present in intestinal neuromuscular tissue through cholinergic neurons. Trudel et al.54 showed that ghrelin increases gastric emptying and small intestinal transit in normal rats, and that ghrelin can be a strong prokinetic to reverse postoperative gastric ileus in rats. Ghrelin induces fasting motor activity in fed rats, suggesting its importance in physiological regulation of GI motility.

Acyl-ghrelin has a limited half-life. Small molecule ghrelin receptor55 agonists had been developed to have enhanced stability and binding affinity to the ghrelin receptor in order to accelerate gastric emptying by antropyloric contractions in animal models of delayed gastric emptying.56 Administration of ghrelin induces a premature gastric phase III without the mediation by motilin in humans.8 In rodents, ghrelin also stimulates phase III-like contractions.14,57 Through ghrelin infusion in conscious freely moving rats, Taniguchi et al.58 showed an increase of motility index of antral phase III-like contractions in a dose-dependent manner. An intravenous (IV) injection of GHS-R antagonist in rats also blocks the effect of IV injection of acyl-ghrelin on gastroduodenal motility.14 In dogs, IV injection of synthesized canine ghrelin stimulates GH production but not digestive tract motility.59 Studies have suggested that acyl-ghrelin originating from the stomach may act on ghrelin receptors localizing to the vagal afferent nerve terminal and neuropeptide Y neurons in the brain in order to mediate gastroduodenal motility.

Des-acyl ghrelin could disrupt fasted motility in the antrum but not in the duodenum. However, des-acyl ghrelin does not alter motility in either the antrum or duodenum.25,60 It was also proposed that ghrelin may have a role in many disorders involving abnormal gastric emptying rate such as Prader-Willi syndrome and dyspepsia.18,61

2. FD

FD is a common functional GI disorder. Epidemiological studies report that approximately 8% to 23% of Asians suffer from FD.62 FD is characterized by chronic recurrent epigastric symptoms including pain, burning, and postprandial fullness.63 The pathophysiological mechanisms of FD remain unclear, although visceral hypersensitivity, impaired fundic accommodation, and gastric dysmotility are common proposed mechanisms. FD is classified into two major subtypes according to Rome III classification. The first subtype involves meal-induced dyspeptic symptoms, and is known as postprandial distress syndrome (PDS). It is characterized by postprandial fullness and early satiation. The second subtype involves epigastric pain and burning, and is called epigastric pain syndrome.63

Lee et al.'s study64 found that preprandial ghrelin levels are significantly lower in FD patients with delayed gastric emptying as predominant symptoms. Moreover, low preprandial ghrelin levels were observed in patients with dysmotility-like FD.64 Shindo et al.65 also revealed that the maximum gastric emptying time, Tmax, for PDS is significantly higher with significant lower acyl-ghrelin levels in these patients. Lower acyl-ghrelin levels were also found in nonerosive reflux disease patients. There is an established correlation between PDS patients in acyl-ghrelin levels and Tmax, suggesting acyl-ghrelin's role in gastric emptying of PDS patients.65

3. Celiac disease

Celiac disease is a chronic immune-mediated disorder. It is a T cell-mediated, gluten-sensitive enteropathy characterized by accumulation of intraepithelial CD8+ and CD4+ T cells sensitized to gliadin in the lamina propria, atrophy of small intestinal villi, intestinal malabsorption, and a negative energy balance. Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in patients with active celiac disease have been reported. However, plasma ghrelin levels return to normal or near normal levels after following a gluten-free diet.66 Furthermore, Capristo et al.67 showed no difference in ghrelin levels between untreated celiac patients and healthy controls and therefore suggested that the discrepancy may be affected by gender, age, and disease duration. Since ghrelin has high structural similarity to the duodenal motility peptide motilin, and exogenous ghrelin stimulates GI motility in normal human subjects,8 ghrelin may play a role in abnormal gastric emptying in celiac disease.

4. IBS

IBS is a functional GI disorder characterized by abdominal bloating, altered bowel habits, pain, and discomfort without a clearly identifiable organic disease. Approximately 8.6% of Japanese and 9.8% of Singaporeans are affected.68 The subtypes of IBS can be classified into constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, or a mix of both.69 Serotonin and motilin have been altered in IBS patients. A study showed enhanced motilin in diarrhea-predominant patients,70 while another study showed increased motilin in diarrhea-predominant and constipation-predominant patients.71 Despite finding no difference of plasma ghrelin concentration, Sjolund et al.29 reported that the ratio of acyl-ghrelin to total ghrelin decreases. El-Salhy et al.72 demonstrated that ghrelin-producing cells are suppressed in constipation-predominant IBS patients, while IBS patients have significantly higher ghrelin-positive cells in the oxyntic mucosa compared to normal controls. All these findings suggested that altered ghrelin modulators may subsequently affect gut motility, and may thus contribute to the pathophysiology of IBS.

GHRELIN IN GI INFLAMMATORY DISORDERS

1. Inflammatory bowel diseases

Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis are inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) that are characterized by chronic inflammation of the GI tract. Symptoms include anorexia, malnutrition, altered body composition, and metabolic abnormalities. Ghrelin was suggested to be an important biomarker for activity determination in IBD patients. Serum ghrelin levels were found to be higher in ulcerative colitis patients and also higher in ileal Crohn disease patients compared to colonic disease patients.73 Ghrelin is also significantly elevated in active IBD patients and positively correlated with serum inflammatory markers like tumor necrosis factor-a, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and sedimentation fibrinogen.74 Furthermore, increased plasma and colonic ghrelin expression was found in IBD patients.75

GHRELIN MODULATORS AS TREATMENTS FOR GI DISORDERS

1. Gastroparesis and gastric dysmotility

Ghrelin was found to stimulate gastric contractions in rats.7 Ghrelin could accelerate gastric emptying and small intestinal transit of a liquid meal.54 It was recognized to be a strong prokinetic agent that could reverse postoperative gastric ileus in conscious rats.54 Trudel et al.76 showed similar improvement of postoperative gastric ileus in dogs.

In human studies, ghrelin was found to stimulate motility and gastric emptying both in healthy individuals and gastroparetic patients. Ghrelin was found to stimulate a faster rate of gastric emptying and administration of ghrelin to healthy subjects also results in premature phase II motility and increased gastric tone.8 Furthermore, administration of ghrelin also showed acceleration of liquid and solid gastric emptying and reduced meal-related symptoms in a study of patients with idiopathic gastroparesis.77 IV administration of ghrelin receptor agonists (80 µg/kg of TZP101) also showed symptom improvement as evaluated both by patients and clinicians.78

2. Appetite stimulation in cancer patients

Ghrelin's role in appetite stimulation was first discovered as a side effect in a study of the effect of ghrelin injection on GH regulation in healthy controls.5 Ghrelin was later identified as a peripheral orexigenic hormone that can stimulate food intake in a dose-dependent manner in rodents and humans.9 IV and subcutaneous injection was shown to stimulate food intake in multiple studies.6,9 Peripheral injection of ghrelin also stimulates food intake, although it cannot pass the blood-brain barrier. Plasma ghrelin levels are increased by fasting and decreased after ingestion of a meal or oral glucose, but remain unchanged after drinking water.6

In a rat cancer model, food intake improved after 6 days of twice daily intraperitoneal ghrelin injections.79 Chronic intracerebroventricular injection of ghrelin increases overall food intake and also decreases the metabolic rate, leading to increased body weight. Similar results have been achieved in ghrelin-treated mice.

Rikkunshito is a kampo herbal medicine for treatment of upper GI symptoms of patients with FD, gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspeptic symptoms of post-GI surgery patients.80 Rikkunshito was proposed to potentiate the orexigenic action of ghrelin by various mechanisms.81 From these emerging findings, we believe that increasing ghrelin availability especially in end-stage cancer patients may improve their appetite and energy homestasis.

3. Anti-inflammatory treatment in IBD

The effect of ghrelin treatment in IBD has only been studied in animal models of colitis. Gonzalez-Rey et al.82 demonstrated a set of experiments on IBD and found that ghrelin treatment produced a near-total amelioration of multiple findings of colitis, inducing weight loss, histological colitis score, survival, and myeloperoxidase activity in the colon. In the dextran sulfate sodium model of colitis in mice, there was also body weight improvement and 67% decreased disease activity by ghrelin administration.82

CONCLUSIONS

Since the discovery of ghrelin, it has been found to have multiple functions. Besides its roles in growth and proliferation, ghrelin is also a potent prokinetic peptide that can stimulate appetite and gastric motility. Recent discoveries have also suggested its involvement in various GI disorders such as gastritis, GI tract carcinoma, and functional GI disorders. Gastric disorders likely disrupt the morphological structure of the stomach, thus altering ghrelin production, since the stomach is its major source. These alterations may induce various GI disorders including functional GI disorders, eating disorders, abnormal energy homeostasis and growth. By understanding ghrelin secretion in the regulation of GI disorders, ghrelin levels may serve as a good diagnostic biomarker for early detection of GI disorders.

We strongly believe that ghrelin will be a new therapeutic target for various GI disorders, especially functional GI disorders, and useful for appetite stimulation in patients with cachexia.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.De Silva A, Bloom SR. Gut hormones and appetite control: a focus on PYY and GLP-1 as therapeutic targets in obesity. Gut Liver. 2012;6:10–20. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Kangawa K. Clinical endocrinology and metabolism. Ghrelin, a novel growth-hormone-releasing and appetite-stimulating peptide from stomach. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;18:517–530. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sato T, Nakamura Y, Shiimura Y, Ohgusu H, Kangawa K, Kojima M. Structure, regulation and function of ghrelin. J Biochem. 2012;151:119–128. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Mizushima T, Shimizu S, Kangawa K. Structural divergence of human ghrelin. Identification of multiple ghrelin-derived molecules produced by post-translational processing. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:64–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvat E, Di Vito L, Broglio F, et al. Preliminary evidence that Ghrelin, the natural GH secretagogue (GHS)-receptor ligand, strongly stimulates GH secretion in humans. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23:493–495. doi: 10.1007/BF03343763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tschöp M, Smiley DL, Heiman ML. Ghrelin induces adiposity in rodents. Nature. 2000;407:908–913. doi: 10.1038/35038090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–908. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, et al. Influence of ghrelin on interdigestive gastrointestinal motility in humans. Gut. 2006;55:327–333. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, et al. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409:194–198. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings DE, Purnell JQ, Frayo RS, Schmidova K, Wisse BE, Weigle DS. A preprandial rise in plasma ghrelin levels suggests a role in meal initiation in humans. Diabetes. 2001;50:1714–1719. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tschöp M, Wawarta R, Riepl RL, et al. Post-prandial decrease of circulating human ghrelin levels. J Endocrinol Invest. 2001;24:RC19–RC21. doi: 10.1007/BF03351037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan HS, Cummings DE, Pepe MS, Breen PA, Matthys CC, Weigle DS. Postprandial suppression of plasma ghrelin level is proportional to ingested caloric load but does not predict intermeal interval in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1319–1324. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima M, Kangawa K. Structure and function of ghrelin. Results Probl Cell Differ. 2008;46:89–115. doi: 10.1007/400_2007_049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujino K, Inui A, Asakawa A, Kihara N, Fujimura M, Fujimiya M. Ghrelin induces fasted motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract in conscious fed rats. J Physiol. 2003;550(Pt 1):227–240. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Brown MS, Liang G, Grishin NV, Goldstein JL. Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell. 2008;132:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monteleone P, Serritella C, Martiadis V, Scognamiglio P, Maj M. Plasma obestatin, ghrelin, and ghrelin/obestatin ratio are increased in underweight patients with anorexia nervosa but not in symptomatic patients with bulimia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4418–4421. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia JM, Garcia-Touza M, Hijazi RA, et al. Active ghrelin levels and active to total ghrelin ratio in cancer-induced cachexia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2920–2926. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DelParigi A, Tschöp M, Heiman ML, et al. High circulating ghrelin: a potential cause for hyperphagia and obesity in prader-willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:5461–5464. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung CK, Lee Y, Chan Y, et al. Decreased basal and postprandial plasma acylated Ghrelin in female patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5 Suppl 1):S-170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin: two major forms of rat ghrelin peptide in gastrointestinal tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:909–913. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stengel A, Keire D, Goebel M, et al. The RAPID method for blood processing yields new insight in plasma concentrations and molecular forms of circulating gut peptides. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5113–5118. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosoda H, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Purification and characterization of rat des-Gln14-Ghrelin, a second endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21995–22000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002784200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nogueiras R, Williams LM, Dieguez C. Ghrelin: new molecular pathways modulating appetite and adiposity. Obes Facts. 2010;3:285–292. doi: 10.1159/000321265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen CY, Inui A, Asakawa A, et al. Des-acyl ghrelin acts by CRF type 2 receptors to disrupt fasted stomach motility in conscious rats. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:8–25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inhoff T, Mönnikes H, Noetzel S, et al. Desacyl ghrelin inhibits the orexigenic effect of peripherally injected ghrelin in rats. Peptides. 2008;29:2159–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang JV, Ren PG, Avsian-Kretchmer O, et al. Obestatin, a peptide encoded by the ghrelin gene, opposes ghrelin's effects on food intake. Science. 2005;310:996–999. doi: 10.1126/science.1117255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chartrel N, Alvear-Perez R, Leprince J, et al. Comment on "obestatin, a peptide encoded by the ghrelin gene, opposes ghrelin's effects on food intake". Science. 2007;315:766. doi: 10.1126/science.1135047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjolund K, Ekman R, Wierup N. Covariation of plasma ghrelin and motilin in irritable bowel syndrome. Peptides. 2010;31:1109–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang N, Yuan C, Li Z, et al. Meta-analysis of the relationship between obestatin and ghrelin levels and the ghrelin/obestatin ratio with respect to obesity. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:48–55. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181ec41ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harsch IA, Koebnick C, Tasi AM, Hahn EG, Konturek PC. Ghrelin and obestatin levels in type 2 diabetic patients with and without delayed gastric emptying. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2161–2166. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown JC, Mutt V, Dryburgh JR. The further purification of motilin, a gastric motor activity stimulating polypeptide from the mucosa of the small intestine of hogs. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1971;49:399–405. doi: 10.1139/y71-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helmstaedter V, Kreppein W, Domschke W, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of motilin in endocrine non-enterochromaffin cells of the small intestine of humans and monkey. Gastroenterology. 1979;76(5 Pt 1):897–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruppin H, Domschke S, Domschke W, Wünsch E, Jaeger E, Demling L. Effects of 13-nle-motilin in man: inhibition of gastric evacuation and stimulation of pepsin secretion. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1975;10:199–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christofides ND, Long RG, Fitzpatrick ML, McGregor GP, Bloom SR. Effect of motilin on the gastric emptying of glucose and fat in humans. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutierrez JA, Solenberg PJ, Perkins DR, et al. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6320–6325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800708105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao TJ, Liang G, Li RL, et al. Ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) is essential for growth hormone-mediated survival of calorie-restricted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7467–7472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002271107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howard AD, Feighner SD, Cully DF, et al. A receptor in pituitary and hypothalamus that functions in growth hormone release. Science. 1996;273:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Wang P, Zheng H, Smith RG. Ghrelin stimulation of growth hormone release and appetite is mediated through the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4679–4684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305930101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zigman JM, Nakano Y, Coppari R, et al. Mice lacking ghrelin receptors resist the development of diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3564–3572. doi: 10.1172/JCI26002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Checchi S, Montanaro A, Pasqui L, et al. Serum ghrelin as a marker of atrophic body gastritis in patients with parietal cell antibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4346–4351. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall BJ. The Campylobacter pylori story. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;146:58–66. doi: 10.3109/00365528809099131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tatsuguchi A, Miyake K, Gudis K, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on ghrelin expression in human gastric mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2121–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isomoto H, Nakazato M, Ueno H, et al. Low plasma ghrelin levels in patients with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Am J Med. 2004;117:429–432. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jang EJ, Park SW, Park JS, et al. The influence of the eradication of Helicobacter pylori on gastric ghrelin, appetite, and body mass index in patients with peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(Suppl 2):S278–S285. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papotti M, Cassoni P, Volante M, Deghenghi R, Muccioli G, Ghigo E. Ghrelin-producing endocrine tumors of the stomach and intestine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5052–5059. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.10.7918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Volante M, Allìa E, Gugliotta P, et al. Expression of ghrelin and of the GH secretagogue receptor by pancreatic islet cells and related endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1300–1308. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mottershead M, Karteris E, Barclay JY, et al. Immunohistochemical and quantitative mRNA assessment of ghrelin expression in gastric and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:405–409. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.038356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang Q, Fan YZ, Ge BJ, Zhu Q, Tu ZY. Circulating ghrelin in patients with gastric or colorectal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:803–809. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9508-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.An JY, Choi MG, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Jin DK, Kim S. Clinical significance of ghrelin concentration of plasma and tumor tissue in patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Res. 2007;143:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waseem T, Javaid Ur R, Ahmad F, Azam M, Qureshi MA. Role of ghrelin axis in colorectal cancer: a novel association. Peptides. 2008;29:1369–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edholm T, Levin F, Hellström PM, Schmidt PT. Ghrelin stimulates motility in the small intestine of rats through intrinsic cholinergic neurons. Regul Pept. 2004;121:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, et al. Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G948–G952. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00339.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Kriegsman M, Nelson R. Ghrelin as a target for gastrointestinal motility disorders. Peptides. 2011;32:2352–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ariga H, Nakade Y, Tsukamoto K, et al. Ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying via early manifestation of antro-pyloric coordination in conscious rats. Regul Pept. 2008;146:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng J, Ariga H, Taniguchi H, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Ghrelin regulates gastric phase III-like contractions in freely moving conscious mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taniguchi H, Ariga H, Zheng J, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Effects of ghrelin on interdigestive contractions of the rat gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6299–6302. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohno T, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, et al. Ghrelin does not stimulate gastrointestinal motility and gastric emptying: an experimental study of conscious dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:129–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fujimiya M, Ataka K, Asakawa A, Chen CY, Kato I, Inui A. Regulation of gastroduodenal motility: acyl ghrelin, des-acyl ghrelin and obestatin and hypothalamic peptides. Digestion. 2012;85:90–94. doi: 10.1159/000334654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cummings DE, Clement K, Purnell JQ, et al. Elevated plasma ghrelin levels in Prader Willi syndrome. Nat Med. 2002;8:643–644. doi: 10.1038/nm0702-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, et al. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:235–244. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee KJ, Cha DY, Cheon SJ, Yeo M, Cho SW. Plasma ghrelin levels and their relationship with gastric emptying in patients with dysmotility-like functional dyspepsia. Digestion. 2009;80:58–63. doi: 10.1159/000215389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shindo T, Futagami S, Hiratsuka T, et al. Comparison of gastric emptying and plasma ghrelin levels in patients with functional dyspepsia and non-erosive reflux disease. Digestion. 2009;79:65–72. doi: 10.1159/000205740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lanzini A, Magni P, Petroni ML, et al. Circulating ghrelin level is increased in coeliac disease as in functional dyspepsia and reverts to normal during gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:907–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Capristo E, Farnetti S, Mingrone G, et al. Reduced plasma ghrelin concentration in celiac disease after gluten-free diet treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:430–436. doi: 10.1080/00365520510012028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gwee KA, Wee S, Wong ML, Png DJ. The prevalence, symptom characteristics, and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in an asian urban community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:924–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Der Veek PP, Biemond I, Masclee AA. Proximal and distal gut hormone secretion in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:170–177. doi: 10.1080/00365520500206210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simrén M, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H. High interdigestive and postprandial motilin levels in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.El-Salhy M, Lillebø E, Reinemo A, Salmelid L. Ghrelin in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Mol Med. 2009;23:703–707. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karmiris K, Koutroubakis IE, Xidakis C, Polychronaki M, Voudouri T, Kouroumalis EA. Circulating levels of leptin, adiponectin, resistin, and ghrelin in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:100–105. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000200345.38837.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ates Y, Degertekin B, Erdil A, Yaman H, Dagalp K. Serum ghrelin levels in inflammatory bowel disease with relation to disease activity and nutritional status. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2215–2221. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hosomi S, Oshitani N, Kamata N, et al. Phenotypical and functional study of ghrelin and its receptor in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1205–1213. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trudel L, Bouin M, Tomasetto C, et al. Two new peptides to improve post-operative gastric ileus in dog. Peptides. 2003;24:531–534. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tack J, Depoortere I, Bisschops R, Verbeke K, Janssens J, Peeters T. Influence of ghrelin on gastric emptying and meal-related symptoms in idiopathic gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:847–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ejskjaer N, Dimcevski G, Wo J, et al. Safety and efficacy of ghrelin agonist TZP-101 in relieving symptoms in patients with diabetic gastroparesis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:1069–e1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hanada T, Toshinai K, Kajimura N, et al. Anti-cachectic effect of ghrelin in nude mice bearing human melanoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)03028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Takiguchi S, Hiura Y, Takahashi T, et al. Effect of rikkunshito, a Japanese herbal medicine, on gastrointestinal symptoms and ghrelin levels in gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:167–174. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takeda H, Muto S, Nakagawa K, Ohnishi S, Asaka M. Rikkunshito and ghrelin secretion. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:4827–4838. doi: 10.2174/138161212803216933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gonzalez-Rey E, Chorny A, Delgado M. Therapeutic action of ghrelin in a mouse model of colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1707–1720. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]