Abstract

Background/Aims

Sequential therapy (ST) for Helicobacter pylori infection in countries other than Korea has shown higher eradication rates than triple therapy (TT). The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of ST in Korea by performing a meta-analysis.

Methods

We performed a comprehensive literature search on the efficacy of ST as a first-line therapy. The odds ratios (ORs) of eradicating H. pylori infection after ST compared with TT were pooled. Pooled estimates of the eradication rates of ST and TT were also calculated.

Results

A total of six studies provided data on 1,759 adult patients. The ORs for the intention to treat (ITT) and the per-protocol (PP) eradication rate were 1.761 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.403 to 2.209) and 1.966 (95% CI, 1.489 to 2.595). Pooled estimates of the ITT and PP eradication rate were 79.4% (95% CI, 76.3% to 82.2%) and 86.4% (95% CI, 83.5% to 88.8%), respectively, for the ST group, and 68.2% (95% CI, 62.1% to 73.8%) and 78.9% (95% CI, 68.9% to 81.7%), respectively, for the TT group.

Conclusions

Although ST presented a higher eradication rate than TT in Korea, the pooled eradication rates were lower than expected. Further studies are needed to validate ST as a first-line treatment for H. pylori in Korea.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Eradication, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori infection is the major cause of gastritis, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastric cancer, and mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Triple therapy (TT) regimens including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), clarithromycin and amoxicillin has been regarded as first-line regimens for treating H. pylori infection. However, eradication rates of TT has declined primarily due to increased bacterial resistance to clarithromycin.1 For this reason, several regimens have been proposed as an alternative to the TT regimen. The sequential therapy (ST) consists of a PPI and amoxicillin for the first 5 days followed by a PPI and two other antibiotics for the following 5 days.2 Several meta-analyses demonstrated that ST regimens achieved higher eradication rates than the standard TT regimen.3-6 However, most of the studies included in these meta-analyses were from Italy, specifically from Rome and Foggia. Few of these meta-analyses included studies from Asia, especially Korea. We cannot conclude that ST will be superior to TT based on the results of these meta-analyses because patterns of antimicrobial resistance may vary geographically. In Korea, the antibiotics resistance rate of H. pylori since the year 2000 was reported to be 13.8% to 38.5% for clarithromycin, 27.6% to 66.2% for metronidazole, 4.5% to 34.6% for tetracycline, 4.8% to 18.5% for amoxicillin, and 4.5% to 29.5% for levofloxacin.7,8 The increased antibiotic resistance of H. pylori has become a significant limitation for eradication in Korea. The purpose of this study was to perform a meta-analysis of studies that targeted the Korean population and compare ST with TT for eradication of H. pylori.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Search methods

A comprehensive literature search was performed to identify all relevant studies that compared ST with TT for H. pylori infection in Korea. Several databases were searched including MEDLINE (through PubMed), EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library for the period 2000 to 2012. We also searched KoreaMed which is a local electronic database providing information on Korean medical published research. The key words used in the search were "Helicobacter pylori," "sequential therapy," "triple therapy," and "standard therapy." We also searched the reference of screened articles and review articles to identify any additional studies.

2. Study selection

Potential studies were initially screened by two researchers (J.S.K, B.W.K.) based on the title and abstract to exclude irrelevant articles. Afterwards, the full texts of all selected studies were screened according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: 1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ST with TT for H. pylori eradication; 2) studies targeting the Korean population; 3) patients were H. pylori treatment naïve and had not used a PPI, histamine-2-receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the preceding month; 4) intention to treat (ITT) analysis; 5) patients were confirmed of H. pylori infection and eradication by at least one of the following methods: rapid urease test, H. pylori stool antigen test, histology, or urea breath test. Nonrandomized studies, case reports, letters, editorials, commentaries, reviews, and abstracts were excluded.

3. Data collection

A data extraction manual was developed and information was collected independently by the two researchers (J.S.K., B.W.K.) using the predefined extraction manual. Disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus by the two researchers. From each report, researchers independently retrieved information including year of publication, whether the study was a single or multicenter study, enrollment period, numbers of patients included in the ST and TT group, baseline characteristics of the patients, details related to the use of ST and TT (including dose and duration), methods of diagnosing infection and confirming eradication; incidence of side effects. The quality of the studies were assessed by the Jadad scoring system based on method of randomization, level of blinding and description of withdrawal and dropouts.9 We considered RCTs with a score of 3 or greater to be high quality. In one RCT, participants of the TT group were randomly assigned to three groups according to treatment duration: 7-, 10-, and 14-day regimens.10 Since the object of our review was to compare ST with TT, we combined all the TT therapy arms into a single TT group. The primary outcome of this study was odds ratios (OR) of successful H. pylori eradication comparing ST with TT. Secondary outcomes were pooled estimates of eradication rates of TT and ST and adverse events during eradication. The eradication rates were considered both on an ITT and on a per-protocol (PP) basis.

4. Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed by calculating pooled estimates of primary and secondary end points. Pooled results were derived by using the fixed effects model, unless significant heterogeneity was present, in which case the random effects model was applied. Forest plots were constructed for visual display of individual studies and pooled results. Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated with the Cochran Q test and the inconsistency index (I2). Values of I2 below 25% and 50%, and above 75% were assumed to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Funnel plots were used to investigate whether publication bias may have adversely affected the results for the primary and secondary end-points. We also carried out Egger regression test and Begg rank correlation tests to further investigate publication bias. Statistical analyses were executed by the aid of Comprehensive Meta-analysis software version 2 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA) with inputs confirmed by both researchers.

RESULTS

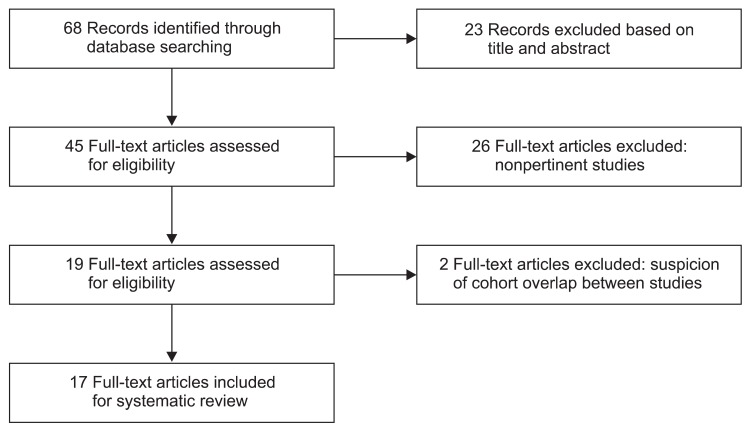

A flow diagram of this systematic review is shown in Fig. 1. In summary, 113 studies were identified by our literature search. One hundred and six studies were excluded after initial screening of title and abstracts. Full-text of the seven remaining articles was reviewed and one article was removed. The remaining six RCTs were eligible for meta-analysis.10-15

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies included in this meta-analysis.

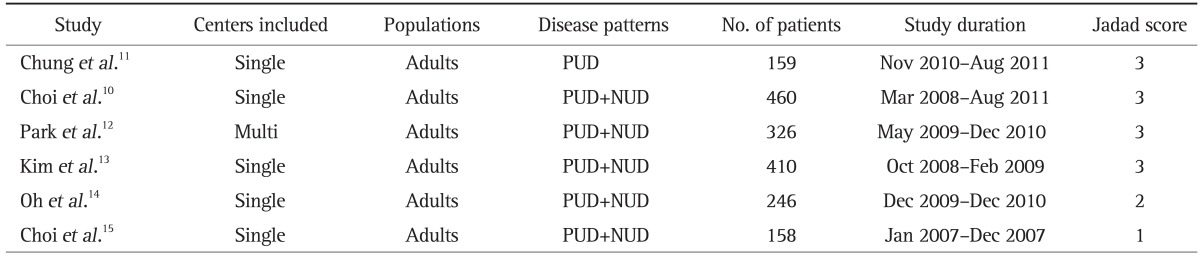

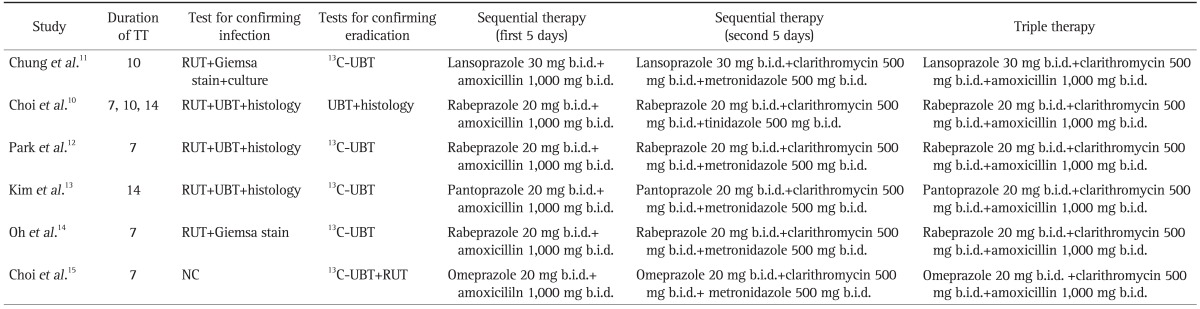

All the RCTs were conducted in Korea and all the studies were performed in adults. The main characteristics of the studies are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All but one of the included studies was a single-center study, and the enrollment period ranged from 2007 to 2011. Choi et al.10 used tinidazole instead of metronidazole while the other five studies used metronidazole in their ST regimen. Four different PPIs (lansoprazole, rabeprazole, omepraozle, pantoprazole) were used in the ST and TT regimen. Except for these two differences the dosage and drugs used in the ST and TT regimen were basically the same. In all 754 patients were treated with ST and 1,005 patients were treated with TT.

Table 1.

Main Characteristics of Included Studies

PUD, peptic ulcer disease; NUD, nonulcer dyspepsia.

Table 2.

Data Abstracted from Included Studies

TT, triple therapy; RUT, rapid urease test; UBT, urea breath test; b.i.d., twice a day; NC, not commented.

1. Pooled eradication rates

The pooled eradication rates of ITT analysis was 79.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 76.3% to 82.2%) for ST with the fixed effects model and 68.2% (95% CI, 62.1% to 73.8%) for TT with the random effects model. The pooled eradication rates of PP analysis was 86.4% (95% CI, 83.5% to 88.8%) for ST with the fixed effects model and 75.9% (95% CI, 68.9% to 81.7%) for TT with the random effects model.

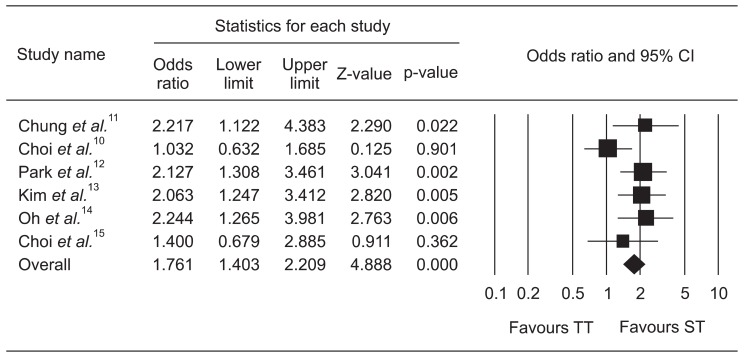

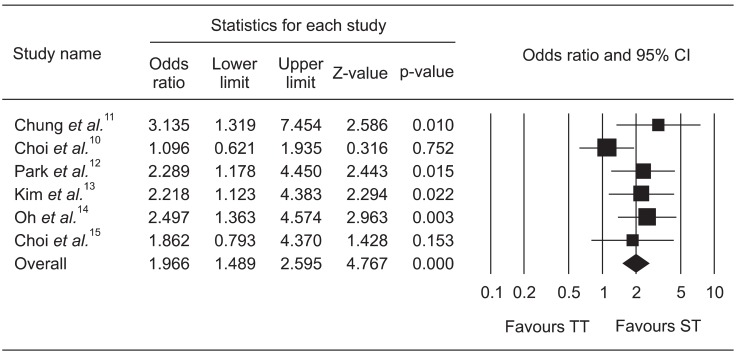

The pooled OR of ITT eradication rates was 1.761 (95% CI, 1.403 to 2.209) with the fixed effects model (Fig. 2) and the pooled OR of PP eradication rates was 1.966 (95% CI, 1.489 to 2.595) with the fixed effects model (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the intention-to-treat analysis of sequential therapy (ST) compared with triple therapy (TT).

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3.

Forrest plot of the per-protocol analysis of sequential therapy (ST) compared with triple therapy (TT).

CI, confidence interval.

2. Adverse events

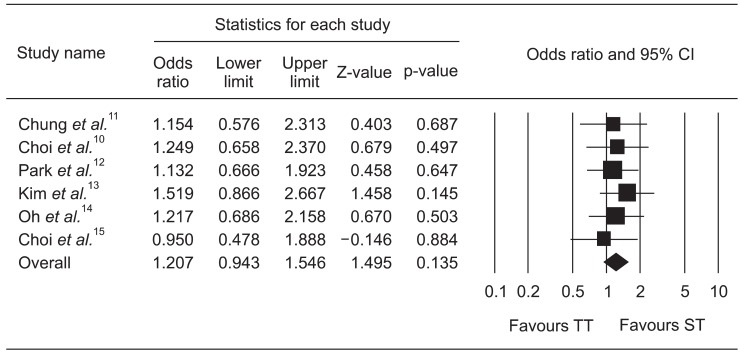

Pooled estimates of incidence of adverse events by the random effects model was 23.8% (95% CI, 18.8% to 29.5%) for ST and 20.3% (95% CI, 14.2% to 28.3%) for TT. The pooled OR of adverse events with the fixed effect model was 1.207 (95% CI, 0.943 to 1.546); indicating no significant difference (p=0.135) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forrest plot of the adverse events associated with sequential therapy (ST) compared with triple therapy (TT).

CI, confidence interval.

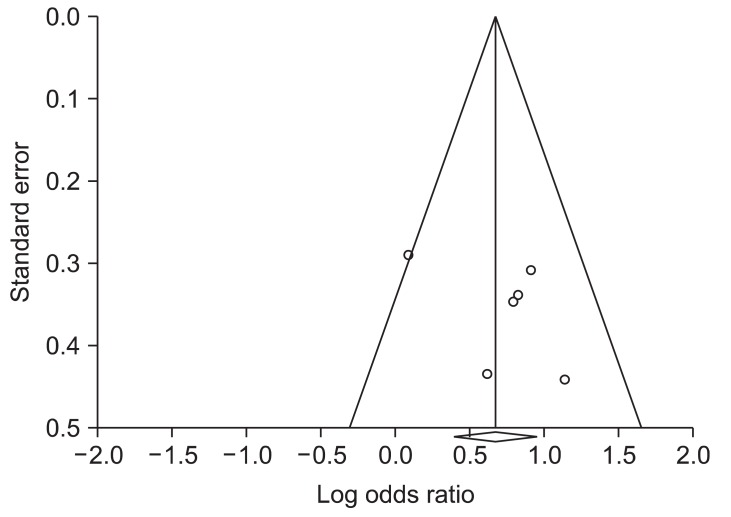

3. Publication bias

No evidence of publication bias was observed for H. pylori eradication rates with ST compared with TT as indicated by a symmetric funnel plot and a nonsignificant Begg test (p=0.35356) and Egger test (p=0.13983) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot asymmetry test for the detection of bias within the studies for the eradication rate of sequential therapy compared with triple therapy.

DISCUSSION

Although, TT regimen is the first-line choice of treatment for H. pylori infection, the efficacy of this regimen has been constantly decreasing worldwide.1,16-18 The ST regimen is a novel therapeutic approach and has shown higher eradication rates than conventional TT in several recent meta-analyses. The eradication rates with ST were greater than 90% in these reports.3-6 However, the studies included in these meta-analyses were published before October 2008 and included studies mostly from Italy. Subsequent meta-analysis including reports published after October 2008 and including studies from other countries have reported eradication rates of the ST to be of 80.6%.19 In addition, studies from Latin America showed that ST was not better than TT.20 These findings suggest that the relative effectiveness of ST regimen varies between geographical regions. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis including studies that involved the Korean population, to investigate the effectiveness of the ST regimen in Korea.

The results of our meta-analysis suggest that ST is superior to TT in the eradication of H. pylori in Korea. We did not identify any study that reported TT to have a higher eradication rate than ST in Korea. Our findings are consistent with previously published meta-analysis that reported ST to be more effective than TT in eradication of H. pylori.3-6 As in previous analysis, our analysis did not find a significant difference in the rate of adverse events between the ST and TT groups. However, the eradication rate of PP analysis was 86.4% for ST which is significantly lower than previous meta-analysis that reported an eradication rate of 93.4%. The reason for this discrepancy may be primarily due to increased bacterial resistance to clarithromycin in Korea. Theoretically, clarithromycin resistance can be overcome with ST. However, a recent study found the eradication rates of ST to be affected by clarithromycin or metronidazole resistance.21 Also, only one of the studies in our analysis used tinidazole and the rest of the studies used metronidazole. This may have affected the eradication rates since metronidazole resistance is reported to be from 27.6% to 66.2% in Korea. The studies included in our analysis did not provide data on clarithromycin or metronidazole resistance and we were not able to examine the effect of antibiotic resistance on eradication in our analysis. Interestingly, the study by Choi et al.,10 which used tinidazole instead of metronidazole found no significant difference between the ST regimen and TT regimen.

The exact mechanism underlying the higher eradication rates of ST compared to TT remains unclear. The sequential administration of antibiotics may have increased the efficacy of clarithromycin in the second phase of treatment. The higher efficiency may also be due to the addition of another drug or it may also be related to increased duration of treatment. We believe additional studies are needed to clarify the mechanism of ST.

Although, ST yielded higher eradication rates than TT, the pooled results of 79.4% for ITT analysis and 86.4% for PP analysis was lower than required. According to the Korean guidelines, treatment regimens for H. pylori infection should achieve ≥90% eradication success for PP analysis and ≥80% for ITT analysis.22 Our results suggest that more evidence is needed before ST is recommended as a first-line eradication regimen. Another problem with the ST regimen is that there is no definite rescue regimen in the eradication failure of patients. Zullo et al.3 reported that a levofloxacin containing triple regimen achieved an eradication rate of 85.7% in patients who failed the ST regimen. However, this observation cannot be applied to the Korean population since primary H. pylori levofloxacin resistance rate has been shown to be as high as 29.5% in Korea.7 To our knowledge, there were no full text articles that investigated treatment of ST failure patients in Korea. Future studies investigating second line regimens after ST failure would be warranted before ST is definitely recommended as first-line regimen in Korea.

There are several limitations to our study. First, most of the studies included in our analysis scored 3 on the Jadad scale and there were no studies with high quality scores (4 or 5). Secondly, there was no reference to blinding in all the trials, which may have overestimated the effect and skew the results in favor of either treatment. Thirdly, a moderate degree of heterogeneity was present and random effects models were used for the estimates of TT eradication rates, ST adverse events and TT adverse events. Fourthly, the data in our studies mostly came from or near Seoul and it might not be representative of the whole Korean population. A prospective multicenter study comparing the effects of ST with TT and targeting the whole Korean population is anticipated.

In conclusion, data from our meta-analysis confirmed higher efficacy of ST as compared to TT. However, the pooled results of ST did not result in a sufficient eradication rate. Further studies regarding the entire Korean population and rescue regimens after ST failure are needed to validate ST as first-line treatment of H. pylori infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article was presented in plenary session of 2012 Annual Scientific Meeting of Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Vakil N, Megraud F. Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:985–1001. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zullo A, Vaira D, Vakil N, et al. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori with a new sequential treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:719–726. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353–1357. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.125658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069–3079. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Xiao SD. Sequential therapy vs. standard triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34:41–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang TJ, Kim N, Kim HB, et al. Change in antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains and the effect of A2143G point mutation of 23S rRNA on the eradication of H. pylori in a single center of Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:536–543. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d04592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim N, Kim YJ, Song IS. Distribution of antibiotic MICs for Helicobacter pylori strains over a 16-year period in patients from Seoul, South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4843–4847. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4843-4847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HS, Chun HJ, Park SH, et al. Comparison of sequential and 7-, 10-, 14-d triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2377–2382. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung JW, Jung YK, Kim YJ, et al. Ten-day sequential versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a prospective, open-label, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1675–1680. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park HG, Jung MK, Jung JT, et al. Randomised clinical trial: a comparative study of 10-day sequential therapy with 7-day standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in naive patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:56–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YS, Kim SJ, Yoon JH, et al. Randomised clinical trial: the efficacy of a 10-day sequential therapy vs. a 14-day standard proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori in Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1098–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh HS, Lee DH, Seo JY, et al. Ten-day sequential therapy is more effective than proton pump inhibitor-based therapy in Korea: a prospective, randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:504–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi WH, Park DI, Oh SJ, et al. Effectiveness of 10 day-sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, et al. Proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and either amoxycillin or nitroimidazole: a meta-analysis of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1319–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuccio L, Minardi ME, Zagari RM, Grilli D, Magrini N, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: duration of first-line proton-pump inhibitor based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:553–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zullo A, Hassan C, Ridola L, De Francesco V, Vaira D. Standard triple and sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication: an update. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:16–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenberg ER, Anderson GL, Morgan DR, et al. 14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin American sites: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378:507–514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liou JM, Chen CC, Chen MJ, et al. Sequential versus triple therapy for the first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:205–213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim N, Kim JJ, Choe YH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:269–278. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.5.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]