Abstract

Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae (formerly Vibrio damsela) is a pathogen of a variety of marine animals including fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and cetaceans. In humans, it can cause opportunistic infections that may evolve into necrotizing fasciitis with fatal outcome. Although the genetic basis of virulence in this bacterium is not completely elucidated, recent findings demonstrate that the phospholipase-D Dly (damselysin) and the pore-forming toxins HlyApl and HlyAch play a main role in virulence for homeotherms and poikilotherms. The acquisition of the virulence plasmid pPHDD1 that encodes Dly and HlyApl has likely constituted a main driving force in the evolution of a highly hemolytic lineage within the subspecies. Interestingly, strains that naturally lack pPHDD1 show a strong pathogenic potential for a variety of fish species, indicating the existence of yet uncharacterized virulence factors. Future and deep analysis of the complete genome sequence of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae will surely provide a clearer picture of the virulence factors employed by this bacterium to cause disease in such a varied range of hosts.

Keywords: Photobacterium damselae, hemolysin, damselysin, hlyA, pore-forming toxin

PHOTOBACTERIUM DAMSELAE SUBSP. DAMSELAE

Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae is a marine bacterium of the family Vibrionaceae that causes infections in a variety of marine animals and also in humans. A bit of historic perspective is necessary in order to understand its current taxonomic placement as well as the changes in its nomenclature during the past decades. In 1971 an “unnamed marine Vibrio” was isolated as the causative agent of a human infectious case (Morris et al., 1982). Later, this same organism was isolated from skin ulcers of damselfish (Chromis punctipinnis) and the name Vibrio damsela was first coined (Love et al., 1981). Further genetic and phenotypic studies indicated that the strains of V. damsela were closely related to species of the genus Photobacterium, and the name Photobacterium damsela was proposed (Smith et al., 1991). In 1995, DNA–DNA hybridization data and 16S rRNA sequence analysis demonstrated that Photobacterium damsela was closely related to a fish pathogen formerly named Pasteurella piscicida, the causative agent of pasteurellosis in fish. Hence, these two organisms were assigned to the same species epithet, Photobacterium damselae, with category of subspecies (Gauthier et al., 1995), Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae and Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida respectively. Despite their similarity at the 16S gene sequence and the high percentage of DNA–DNA relatedness between them, these two subspecies are clearly distinguished by several phenotypical traits (Fouz et al., 1992; Magariños et al., 1992; Thyssen et al., 1998; Botella et al., 2002). Differential phenotypical tests of interest for subspecies discrimination that are positive only for subsp. damselae include motility, nitrate reduction and hemolysis on sheep blood agar. Of special relevance is the ability of most subsp. damselae strains to grow at 37°C (a temperature inhibitory for subsp. piscicida), a trait that allows Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae to potentially colonize and establish an infection in a homeotherm animal.

A PATHOGEN OF MARINE ANIMALS

Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae is an autochthonous member of aquatic ecosystems. Strains of this pathogen have been isolated from sea and estuarine waters, from seaweeds, from apparently uninfected marine animals (Buck et al., 2006; Serracca et al., 2011) and from seafood (Lozano-León et al., 2003; Chiu et al., 2013), and it is considered a common member of the natural microbiota of healthy carcharhinid sharks (Grimes et al., 1985).

In addition, Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae is considered a primary pathogen of several species of wild fish (damselfish, catfish, shark, stingray, etc.), as well as of fish species of economical importance in aquaculture, causing wound infections and hemorrhagic septicemia. Cultivated species reported to be affected by this pathogen include turbot (Psetta maxima; Fouz et al., 1992), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss; Pedersen et al., 2009), ovate pompano (Trachinotus ovatus; Zhao et al., 2009), eel (Anguilla reinhardtii; Ketterer and Eaves, 1992), sea bream (Sparus aurata; Vera et al., 1991), sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), yellowtail (Seriola quinqueradiata), redbanded seabream (Pagrus auriga), white seabream (Diplodus sargus), and meagre (Argyrosomus regius; Labella et al., 2006, 2010a, b), among others. The recent first reports on isolation of this pathogen from diseased marine fish of new cultured species, suggest that Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae can be considered as an emerging pathogen in marine aquaculture (Labella et al., 2011).

Moreover, Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae has been isolated as a pathogen of brown shark (Carcharhinus plumbeus; Grimes et al., 1984), of reptiles as the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea; Obendorf et al., 1987), molluscs (Octopus joubini; Hanlon et al., 1984), crustaceans (Song et al., 1993; Vaseeharan et al., 2007), dolphins (Tursiops truncatus and Delphinus delphis; Fujioka et al., 1988; Buck et al., 1991) and Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni; Buck et al., 1991).

Virulent isolates are capable of survival in seawater microcosms at 14–22°C as culturable bacteria for long periods of time, maintaining their infectivity for fish (Fouz et al., 1998). Similarly, this pathogen can infect new fish hosts through water, and the spread of the disease depends largely on water temperature and salinity (Fouz et al., 2000). Typical signs of the disease in infected fish include hemorrhaged areas on the body surface and ulcerative lesions. In damselfish, ulcers typically occur in the region of the pectoral fin and caudal peduncle and may reach 5–20 mm in diameter (Love et al., 1981), while in turbot the most remarkable symptoms are extensive hemorrhages in eyes, mouth, and jaws (Fouz et al., 1995).

Experimental inoculation of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae extracellular products (ECPs) in a redbanded seabream model was reported to cause lethargy, increase in the respiratory frequency, mucus production, presence of ascitic liquid, hemorrhagic and enlarged liver, and hemorrhages in the abdominal cavity (Labella et al., 2010b). A histological analysis of internal organs in experimentally infected turbot indicated that the ECPs and cells of virulent strains cause similar tissue damage (Fouz et al., 1995). Structural changes included destruction and necrosis of cells, as well as accumulation of blood cells in interstitial tissue.

Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae AS A HUMAN PATHOGEN

Most of the reported infections caused by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae in humans have their primary origin in wounds exposed to salt or brackish water, inflicted during fish and tools handling (Morris et al., 1982; Dryden et al., 1989; Yuen et al., 1993; Shin et al., 1996; Tang and Wong, 1999; Barber and Swygert, 2000; Goodell et al., 2004; Aigbivhalu and Maraqa, 2009). Unusual cases of infection after ingestion of raw seafood (Kim et al., 2009) and through the urinary tract by exposure to sea water (Alvarez et al., 2006) were also reported. The majority of the cases occurred in coastal areas of the United States of America, Australia, and Japan.

Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae can cause an extreme variant of a highly severe necrotizing fasciitis, and antibiotic administration proved unable to control the progression of fatal infections in some cases (Clarridge and Zighelboimdaum, 1985; Fraser et al., 1997; Yamane et al., 2004). It is interesting to note that some authors recommend to surgically debride and amputate without hesitation at a very early point of the infection by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, to save the lives of patients (Goodell et al., 2004). Some patients infected by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae developed multiple organ failure within a few hours from the onset of initial symptoms, despite intensive chemotherapy and surgical treatments. As an example, in a fatal case reported in 1984 in which a patient injured his hand while handling a catfish, bulle formation occurred on the hand and a marked edema extended through the forearm in less than 24 h (Clarridge and Zighelboimdaum, 1985), and although the affected area was extensively debrided the patient died after a series of complications. The bacterium was recovered in high numbers from the tissue sample but only in very small numbers from the bulle fluid. In another fatal case reported in a patient injured while handling fish, Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae was isolated in pure culture from wound specimens but failed to be isolated from blood samples (Fraser et al., 1997). These observations prompted these authors to suggest that a virulence factor or systemic toxin released by this bacterium contributed to the tissue damage and to the fatal outcome, rather than the septicemia itself. However, in other clinical cases this pathogen was recovered from blood (Perez-Tirse et al., 1993; Shin et al., 1996; Yamane et al., 2004).

Necrotizing fasciitis due to Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae demonstrates more serious complications and a higher mortality rate than that caused by Vibrio vulnificus. While V. vulnificus usually affects persons with underlying diseases (as chronic liver disease and diabetes mellitus), necrotizing fasciitis by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae sometimes occurs in healthy hosts (Morris et al., 1982; Perez-Tirse et al., 1993; Yuen et al., 1993).

VIRULENCE FACTORS

Iron uptake systems

Early studies reported that Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae can utilize heme, hemoglobin and ferric ammonium citrate as sole iron sources in vitro (Fouz et al., 1994). The complete sequence of 10 genes encoding a system for the utilization of heme as iron source was described in a human isolate of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, and cloning of the complete system into E. coli conferred to this species the ability to use hemin and hemoglobin as iron sources (Rio et al., 2005). The presence of the heme receptor gene hutA was demonstrated in subsp. damselae isolates from fish and humans, and the identity at the DNA sequence level between the heme uptake clusters of subsp. damselae and subsp. piscicida strains was 97% (Rio et al., 2005). Although no functional studies were conducted with the heme uptake genes of subsp. damselae, it was recently demonstrated that this cluster is essential for heme utilization in subsp. piscicida, and two genes of a hemin ABC-transporter proved to be expressed during the infective process in a fish model (Osorio et al., 2010). Actually, an increase in the susceptibility of both fish and mice to infection by virulent Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains in virulence assays conducted with iron-overloaded animals had been demonstrated in former studies (Fouz et al., 1994). It is also known that this bacterium produces a hydroxamate-type siderophore, and the synthesis of several high-molecular weight outer membrane proteins induced under iron limitation conditions was reported (Fouz et al., 1997). Although the precise chemical structure of the siderophore(s) is so far unknown, recent unpublished work from our laboratory demonstrated that vibrioferrin is being produced by some strains.

Cytotoxins with hemolytic activity

Pioneering studies (Kreger, 1984) reported the existence of a correlation between the ability of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae isolates to cause disease in mice and the production of large amounts of a heat-labile cytolytic toxin in vitro. Later, the same authors purified a toxin that exhibited strong hemolytic activity against erythrocytes of a variety of animal species (Kothary and Kreger, 1985). In subsequent studies, this toxin named damselysin (Dly) was defined as a phospholipase-D active against sphingomyelin, with hemolytic activity (Kreger et al., 1987), and its gene (dly) was cloned and sequenced (Cutter and Kreger, 1990). Dly was thus considered to be the main virulence factor of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae for mice. Further studies reported the existence of hemolytic strains of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae that tested negative for dly gene, which suggested that Dly was not the only hemolysin in the subspecies (Osorio et al., 2000). It was also demonstrated by several authors that presence of dly is not a prerequisite for the hemolytic activity and for the pathogenicity for mice or fish, since dly negative strains bear virulence potential for animals and also toxicity for homeotherm and poikilotherm cell lines (Osorio et al., 2000; Labella et al., 2010b).

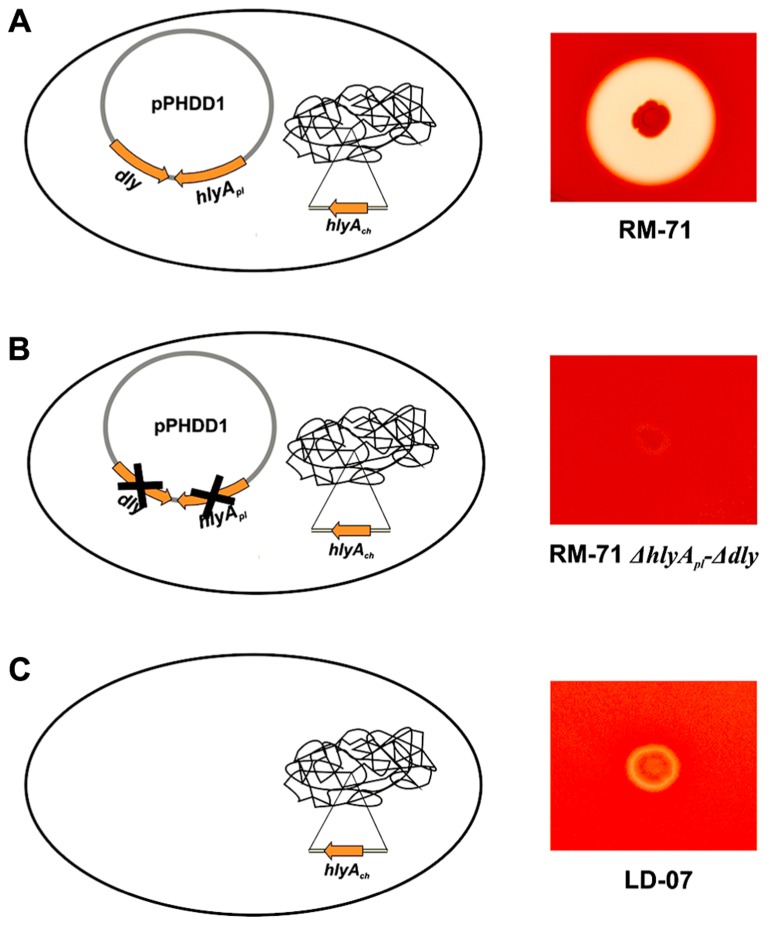

The genomic context of dly gene remained uncharacterized for decades, and it was initially proposed that it could be carried on a mobile or unstable DNA element (Cutter and Kreger, 1990). Recently, the authors’ laboratory identified and characterized a 150 kb plasmid, which was dubbed pPHDD1, that contains the genes for Dly as well as for a HlyA toxin of the pore-forming toxin family (Rivas et al., 2011). Only a fraction of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains harbor pPHDD1, and these strains exhibit a much wider hemolytic halo on sheep blood agar plates than the plasmidless strains (Figure 1). Interestingly, pPHDD1 occurs in both fish and human isolates and it is not restricted to a unique animal host species (Rivas et al., 2011). In addition to being necessary to cause strong hemolytic haloes on blood agar plates, the two pPHDD1-encoded hemolysins play a crucial role in virulence for fish and mice in strains that naturally harbor the plasmid. Hence, mutation of both dly and hlyA genes in a pPHDD1-harboring strain renders the strain non-virulent for fish, and only slightly virulent for mice (Table 1), and the hemolytic phenotype on sheep blood agar of a dly and hlyA double mutant resembles that of naturally plasmidless strains (Figure 1; Rivas et al., 2011, 2013).

FIGURE 1.

Hemolytic phenotypes in sheep blood agar of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains. (A) strains that naturally harbor pPHDD1 plasmid produce the three hemolysins Dly (damselysin), HlyApl, and HlyAch (this last one, encoded in the chromosome), and cause a wide hemolytic halo in sheep blood agar. (B) a double mutant for dly and hlyApl genes shows a weak hemolytic phenotype, similar to that of a naturally plasmidless strain (C), that only produces HlyAch.

Table 1.

Role of the three Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae hemolysins in virulence for mice and fish (turbot).

| Strain | Hemolysin(s) produced | Number of dead mice (n = 15) | Number of dead fish (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental | HlyAch HlyApl Dly | 15 | 15 |

| ΔhlyAch | HlyApl Dly | 13 | 9* |

| ΔhlyApl | HlyAch Dly | 10* | 14 |

| Δdly | HlyAch HlyApl | 10* | 4* |

| ΔhlyAch ΔhlyApl | Dly | 12 | 5* |

| ΔhlyAch Δdly | HlyApl | 9* | 0* |

| ΔhlyApl Δdly | HlyAch | 3* | 0* |

| ΔhlyAch ΔhlyApl Δdly | none | 0* | 0* |

Parental and mutant strains were inoculated in groups of 15 animals, at doses of 2.1 × 106 bacterial cells per mouse and 2.1 × 104 bacterial cells per fish. The number of dead animals out of the total number of inoculated animals (15) is indicated. Asterisks denote that significant differences exist between a given mutant and the parental strain, using U-test (*P < 0.05).

The hemolytic activity exhibited by plasmidless strains was recently demonstrated to be caused by a chromosome-encoded hlyA gene, which was dubbed hlyAch in order to differentiate it from the plasmid hlyA gene (hereafter hlyApl; Rivas et al., 2013). It was found that all the hemolytic Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains harbor hlyAch gene, which is the only hemolytic determinant in plasmidless strains. Thus, pPHDD1-harboring isolates produce three different hemolysins. In hemolytic assays carried out with bacterial ECPs and with sheep erythrocytes, it was demonstrated that Dly acts in a synergistic manner with HlyApl and HlyAch, whereas the effect between HlyApl and HlyAch showed to be additive but not synergistic (Rivas et al., 2013).

Although each of the three hemolysins individually proved to be sufficient to cause death in mice, each one contributes to virulence in a different degree. The contribution of HlyAch to virulence for mice is the lowest among the three toxins. Altogether, albeit the highest values of mortality for mice are achieved only when the three hemolysins are being produced, Dly and HlyApl demonstrated to be main contributors in the virulence of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae for mice (Rivas et al., 2013; Table 1).

Interestingly, the contribution of each hemolysin to virulence was found to vary depending on whether the host animal tested was mouse or turbot. When virulence experiments were conducted with turbot, it was found that among all the hemolysin gene mutants only the Dly-producing strains caused death in fish. This finding demonstrated that any of the two HlyA alone does not cause death in turbot, but rather one of the two HlyA needs the presence of either Dly or the other HlyA to cause death in fish. The production of Dly in combination with any of the two HlyA caused an increase in the number of dead fish with respect to the production of Dly alone, and this increase was found to be particularly evident when Dly was combined with HlyAch. This clearly suggests that, unlike what is observed in mice, the contribution of hemolysins to virulence for fish is not so much based on the individual effects of each hemolysin but rather on the combined (synergistic) effects between Dly and HlyA (Rivas et al., 2013; Table 1). These findings also state the importance of pPHDD1 plasmid in virulence for fish, since Dly is necessary for the synergistic effect.

Other exoenzymes and exotoxins: toxicity of the extracellular products

Early studies detected several enzymatic activities in the ECPs of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, which included phospholipase and hemolysin activities (Fouz et al., 1993). More recent data confirmed that the ECPs of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae are strongly lethal for fish, and enzymatic activities such as amylase, lipase, phospholipase, alkaline phosphatase, esterase–lipase, acid phosphatase, and β -glucosaminidase were evidenced (Labella et al., 2010b). Moreover, treatment at 100°C for 10 min of the ECPs abolished the ability to cause death in fish, suggesting that toxicity was not due to the thermorresistant lipopolysaccharide content. Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae ECPs also displayed cytotoxic activity for different fish and mammalian cell lines (Wang et al., 1998; Labella et al., 2010b). Different studies found a correlation between virulence of the strain and toxicity of the ECPs, with toxicity being limited to ECPs from strains that were also virulent for fish (Fouz et al., 1995; Labella et al., 2010b). Of maximum interest is the observation that strains lacking pPHDD1 plasmid and thus being negative for dly and hlyApl genes, are virulent for fish and their ECPs are cytotoxic for cell lines. In addition, a comprehensive study reported that none of the enzymatic activities detected in the Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae ECPs could be related with the degree of toxicity either in vivo or in vitro (Labella et al., 2010b). Most Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains test negative for protease activities as caseinase and gelatinase (Fouz et al., 1992; Labella et al., 2010b). This suggests that other, yet uncharacterized molecules produced by Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae cells play a role in toxicity for animals and for cell lines. In this regard, previous studies detected the existence of an acetylcholinesterase activity (ictiotoxin) with neurotoxic activity in several species of Vibrionaceae, including Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae (Perez et al., 1998), although the genetic basis for this neurotoxic activity remains unknown.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

An interesting observation that remains to be explained at the genetic level is the finding that plasmidless Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains are virulent for fish and toxic for homeotherm and poikilotherm cell lines (Fouz et al., 1993; Osorio et al., 2000; Labella et al., 2010b, 2011). Since plasmidless strains lack dly and hlyApl genes, and since dly hlyApl double mutants are significantly reduced in its virulence for both mice and fish (Rivas et al., 2013), it is evident that plasmidless strains encode virulence factors that either are not encoded by pPHDD1-harboring strains or their expression is repressed in presence of pPHDD1-encoded genes.

The recent completion of the genome sequence of the type strain (ATCC 33539) of this subspecies (deposited in GenBank database in several separate contigs, under accession number ADBS00000000), allows an in silico analysis to search for candidate genes encoding potential toxins and other virulence factors. The type strain harbors pPHDD1 plasmid, and preliminary analyses also indicated the presence of genes encoding a type III hemolysin (open reading frame number: VDA003208), and a putative murine toxin (VDA000322) among others. The existence of yet uncharacterized plasmids is also evidenced in the complete genome of ATCC 33539. Studies to functionally characterize novel plasmid content and candidate virulence genes of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains are currently under way. It is expected that a deep analysis of the complete genome sequence of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains with different isolation origins and virulence properties will provide a clearer picture of the virulence factors employed by this bacterium to cause disease in such a varied range of hosts.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by grant EM2012/043 from Xunta de Galicia, Spain; and by grants AGL2012-39274-C02-01, from the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) of Spain and CSD2007-00002 (Consolider Aquagenomics) from the Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN) of Spain, both (cofunded by the FEDER Programe from the European Union.

REFERENCES

- Aigbivhalu L., Maraqa N. (2009). Photobacterium damsela wound infection in a 14-year-old surfer. South. Med. J. 102 425–426 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31819b9491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez J. R., Lamba S., Dyer K. Y., Apuzzio J. J. (2006). An unusual case of urinary tract infection in a pregnant woman with Photobacterium damsela. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006 80682 10.1155/IDOG/2006/80682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber G. R., Swygert J. S. (2000). Necrotizing fasciitis due to Photobacterium damsela in a man lashed by a stingray. N. Engl. J. Med. 342 824 10.1056/NEJM200003163421118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella S., Pujalte M. J., Macian M. C., Ferrus M. A., Hernandez J., Garay E. (2002). Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) and biochemical typing of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93 681–688 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J. D., Overstrom N. A., Patton G. W., Anderson H. F., Gorzelany J. F. (1991). Bacteria associated with stranded cetaceans from the Northeast USA and Southwest Florida Gulf coasts. Dis. Aquat. Org. 10 147–152 10.3354/dao010147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buck J. D., Wells R. S., Rhinehart H. L., Hansen L. J. (2006). Aerobic microorganisms associated with free-ranging bottlenose dolphins in coastal Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean waters. J. Wildl. Dis. 42 536–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu T.-H., Kao L.-Y., Chen M.-L. (2013). Antibiotic resistance and molecular typing of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, isolated from seafood. J. Appl. Microbiol. 114 1184–1192 10.1111/jam.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarridge J. E., Zighelboimdaum S. (1985). Isolation and characterization of 2 hemolytic phenotypes of Vibrio damsela associated with a fatal wound infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 21 302–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutter D. L., Kreger A. S. (1990). Cloning and expression of the damselysin gene from Vibrio damsela. Infect. Immun. 58 266–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden M., Legarde M., Gottlieb T., Brady L., Ghosh H. K. (1989). Vibrio damsela wound infections in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 151 540–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Barja J. L., Amaro C., Rivas C., Toranzo A. E. (1993). Toxicity of the extracellular products of Vibrio damsela isolated from diseased fish. Curr. Microbiol. 27 341–347 10.1007/BF01568958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Biosca E. G., Amaro C. (1997). High affinity iron-uptake systems in Vibrio damsela: role in the acquisition of iron from transferrin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 82 157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Larsen J. L., Nielsen B., Barja J. L., Toranzo A. E. (1992). Characterization of Vibrio damsela strains isolated from turbot Scophthalmus maximus in Spain. Dis. Aquat. Org. 12 155–166 10.3354/dao012155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Novoa B., Toranzo A. E., Figueras A. (1995). Histopathological lesions caused by Vibrio damsela in cultured turbot, Scophthalmus maximus (L) – inoculations with live cells and extracellular products. J. Fish Dis. 18 357–364 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1995.tb00312.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Toranzo. A. E., Biosca E. G., Mazoy R., Amaro C. (1994). Role of iron in the pathogenicity of Vibrio damsela for fish and mammals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121 181–188 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Toranzo A. E., Marco-Noales E., Amaro C. (1998). Survival of fish-virulent strains of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae in seawater under starvation conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 168 181–186 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouz B., Toranzo A. E., Milan M., Amaro C. (2000). Evidence that water transmits the disease caused by the fish pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 88 531–535 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S. L., Purcell B. K., Delagdo B., Baker A. E., Whelen A. C. (1997). Rapidly fatal infection due to Photobacterium (Vibrio) damsela. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25 935–936 10.1086/597647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka R. S., Greco S. B., Cates M. B., Schroeder J. P. (1988). Vibrio damsela from wounds in bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus. Dis. Aquat. Org. 4 1–8 10.3354/dao004001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier G., Lafay B., Ruimy R., Breittmayer V., Nicolas J. L., Gauthier M., et al. (1995). Small-subunit ribosomal-RNA sequences and whole DNA relatedness concur for the reassignment of Pasteurella piscicida (Snieszko et al.) Janssen and Surgalla to the genus Photobacterium as Photobacterium damsela subsp. piscicida comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45 139–144 10.1099/00207713-45-1-139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell K. H., Jordan M. R., Graham R., Cassidy C., Nasraway S. A. (2004). Rapidly advancing necrotizing fasciitis caused by Photobacterium (Vibrio) damsela: a hyperaggressive variant. Crit. Care Med. 32 278–281 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104920.01254.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. J., Brayton P., Colwell R. R., Gruber H. (1985). Vibrios as autochthonous flora of neritic sharks. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 6 221–226 10.1016/S0723-2020(85)80056-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. J., Colwell R. R., Stemmler J., Hada H., Maneval D., Hetrick F. M., et al. (1984). Vibrio species as agents of elasmobranch disease. Helgol. Meeresunters 37 309–315 10.1007/BF01989313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon R. T., Forsythe J. W., Cooper K. M., Dinuzzo A. R., Folse D. S., Kelly M. T. (1984). Fatal penetrating skin ulcers in laboratory-reared octopuses. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 44 67–83 10.1016/0022-2011(84)90047-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer P. J., Eaves L. E. (1992). Deaths in captive eels (Anguila reinhardtii) due to Photobacterium (Vibrio) damsela. Aust. Vet. J. 69 203–204 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1992.tb07528.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. R., Kim J. W., Lee M. K., Kim J. G. (2009). Septicemia progressing to fatal hepatic dysfunction in a cirrhotic patient after oral ingestion of Photobacterium damsela: a case report. Infection 37 555–556 10.1007/s15010-009-9049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kothary M. H, Kreger A. S. (1985). Purification and characterization of an extracellular cytolysin produced by Vibrio damsela. Infect. Immun. 49 25–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreger A. S. (1984). Cytolytic activity and virulence of Vibrio damsela. Infect. Immun. 44 326–331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreger A. S., Bernheimer A. W., Etkin L. A., Daniel L. W. (1987). Phospholipase D activity of Vibrio damsela cytolysin and its interaction with sheep erythrocytes. Infect. Immun. 55 3209–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labella A., Berbel C., Manchado M., Castro D., Borrego J. J. (2011). “Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, an emerging pathogen affecting new cultured marine fish species in southern Spain,” in Recent Advances in Fish Farms eds Aral Faruk, Doğu Zafer. (New York: InTech; ) 135–152 [Google Scholar]

- Labella A., Manchado M., Alonso M. C., Castro D., Romalde J. L., Borrego J. J. (2010a). Molecular intraspecific characterization of Photobacterium damselae ssp. damselae strains affecting cultured marine fish. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108 2122–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labella A., Sanchez-Montes N., Berbel C., Aparicio M., Castro D., Manchado M., et al. (2010b). Toxicity of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae strains isolated from new cultured marine fish. Dis. Aquat. Org. 92 31–40 10.3354/dao02275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labella A., Vida M., Alonso M. C., Infante C., Cardenas S., López-Romalde S., et al. (2006). First isolation of Photobacterium damselae ssp. damselae from cultured redbanded seabream, Pagrus auriga Valenciennes, in Spain. J. Fish Dis. 29 175–179 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2006.00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M., Teebkenfisher D., Hose J. E., Farmer J. J., Hickman F. W., Fanning G. R. (1981). Vibrio damsela, a marine bacterium, causes skin ulcers on the damselfish Chromis punctipinnis. Science 214 1139–1140 10.1126/science.214.4525.1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-León A., Osorio C. R., Núnez S., Martínez-Urtaza J., Magariños B. (2003). Occurrence of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae in bivalve molluscs from Northwest Spain. Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 23 40–44 [Google Scholar]

- Magariños B., Romalde J. L., Bandín I., Fouz B., Toranzo A. E. (1992). Phenotypic, antigenic, and molecular characterization of Pasteurella piscicida strains isolated from fish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58 3316–3322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. G., Wilson R., Hollis D. G., Weaver R. E., Miller H. G., Tacket C. O., et al. (1982). Illness caused by Vibrio damsela and Vibrio hollisae. Lancet 319 1294–1297 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92853-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obendorf D. L., Carson J., Mcmanus T. J. (1987). Vibrio damsela infection in a stranded leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). J. Wildl. Dis. 23 666–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio C. R., Juiz-Río S., Lemos M. L. (2010). The ABC-transporter hutCD genes of Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida are essential for haem utilization as iron source and are expressed during infection in fish. J. Fish Dis. 33 649–655 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01169.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio C. R., Romalde J. L., Barja J. L., Toranzo A. E. (2000). Presence of phospholipase-D (dly) gene coding for damselysin production is not a pre-requisite for pathogenicity in Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. Microb. Pathog. 28 119–126 10.1006/mpat.1999.0330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K., Skall H. F., Lassen-Nielsen A. M., Bjerrum L., Olesen N. J. (2009). Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, an emerging pathogen in Danish rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), mariculture. J. Fish Dis. 32 465–472 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2009.01041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez M. J., Rodriguez L. A., Nieto T. P. (1998). The acetylcholinesterase ichthyotoxin is a common component in the extracellular products of Vibrionaceae strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84 47–52 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Tirse J., Levine J. F., Mecca M. (1993). Vibrio damsela~– a cause of fulminant septicemia. Arch. Intern. Med. 153 1838–1840 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410150128012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rio S. J., Osorio C. R., Lemos M. L. (2005). Heme uptake genes in human and fish isolates of Photobacterium damselae: existence of hutA pseudogenes. Arch. Microbiol. 183 347–358 10.1007/s00203-005-0779-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas A. J., Balado M., Lemos M. L., Osorio C. R. (2011). The Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae hemolysins damselysin and HlyA are encoded within a new virulence plasmid. Infect. Immun. 79 4617–4627 10.1128/IAI.05436-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas A. J., Balado M., Lemos M. L., Osorio C. R. (2013). Synergistic and additive effects of chromosomal and plasmid-encoded hemolysins contribute to hemolysis and virulence in Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. Infect. Immun. 81 3287–3299 10.1128/IAI.00155-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serracca L., Ercolini C., Rossini I., Battistini R., Giorgi I., Prearo M. (2011). Occurrence of both subspecies of Photobacterium damselae in mullets collected in the river Magra (Italy). Can. J. Microbiol. 57 437–440 10.1139/w11-021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H., Shin M. G., Suh S. P., Ryang D. W., Rew J. S., Nolte F. S. (1996). Primary Vibrio damsela septicemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22 856–857 10.1093/clinids/22.5.856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. K., Sutton D. C., Fuerst J. A., Reichelt J. L. (1991). Evaluation of the genus Listonella and reassignment of Listonella damsela (Love et al.)MacDonell and Colwell to the genus Photobacterium as Photobacterium damsela comb. nov. with an emended description. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41 529–534 10.1099/00207713-41-4-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. L., Cheng W., Wang C. H. (1993). Isolation and characterization of Vibrio damsela infectious for cultured shrimp in Taiwan. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 61 24–31 10.1006/jipa.1993.1005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. M, Wong J. W. K. (1999). Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Vibrio damsela. Orthopedics 22 443–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyssen A., Grisez L., van Houdt R., Ollevier F. (1998). Phenotypic characterization of the marine pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48 1145–1151 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseeharan B., Sundararaj S., Murugan T., Chen J. C. (2007). Photobacterium damselae ssp. damselae associated with diseased black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon Fabricius in India. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 45 82–86 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera P., Navas J. I., Fouz B. (1991). First isolation of Vibrio damsela from seabream (Sparus aurata). Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 11 112–113 [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. H., Oon H. L., Ho G. W. P., Wong W. S. F., Lim T. M., Leung K. Y. (1998). Internalization and cytotoxicity are important virulence mechanisms in vibrio-fish epithelial cell interactions. Microbiology 144 2987–3002 10.1099/00221287-144-11-2987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane K., Asato J., Kawade N., Takahashi H., Kimura B., Arakawa Y. (2004). Two cases of fatal necrotizing fasciitis caused by Photobacterium damsela in Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42 1370–1372 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1370-1372.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen K. Y., Ma L., Wong S. S. Y., Ng W. F. (1993). Fatal necrotizing fasciitis due to Vibrio damsela. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 25 659–661 10.3109/00365549309008557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. H., Sun J. J., Liu L., Zhao H. H., Wang H. F., Liang L. Q., et al. (2009). Characterization of two phenotypes of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae isolated from diseased juvenile Trachinotus ovatus reared in cage mariculture. J. World Aquacu. Soc. 40 281–289 10.1111/j.1749-7345.2009.00251.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]