Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer screening (CRCS) in the United States is inadequate in minority communities and particularly among those who lack insurance; finding ways to increase screenings among African Americans and Hispanics, presents a major healthcare challenge.

Methods

This study was offered to women attending the Breast Examination Center of Harlem, a community outreach program of Memorial Sloan-Kettering serving the primarily black and Hispanic Harlem Community. Screening was explained, medical fitness was determined, and colonoscopies were performed. Barriers to screening and ways to overcome them were ascertained. Participation was offered to eligible women seen at BECH from July 2003 through October 2005. Participants had to be at least 50 years of age without history of colorectal cancer or screening within the last 10 years.

Results

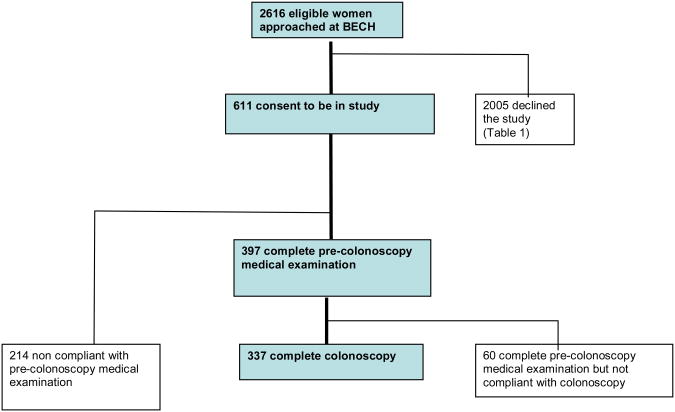

There were 2616 women who were eligible for CRCS, and of these women 2005 (77%) refused to participate in the study, and 611 (23%) women were enrolled. There was a high interest in CRCS including among those who declined to participate in the study. The major barrier was lack of medical insurance which was overcome by alternative funding. Of the 611 women enrolled, 337 (55%) went on to have screening colonoscopy. Forty-nine women (15%) had adenomatous polyps.

Conclusions

Offering CRCS to poor minority women at the time of mammography and without a doctor's referral is an effective way to expand screening. Screening colonoscopy findings are similar to those in the general population. Alternatives to traditional medical insurance are needed for the uninsured.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy, underserved population, uninsured

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the United States, with an estimated 148,810 new diagnoses and 49,960 deaths in 2008 alone.1 CRC screening (CRCS) by fecal occult blood testing has been shown to reduce mortality. Although randomized studies of colonoscopy have not been performed, indications are that colonoscopy is particularly effective for CRCS.2-4 All colorectal cancer screening strategies cost less than $20,000 per life-year saved.5 This is comparable to the cost effectiveness of mammography.5

In spite of the proven efficacy of CRCS, no more than 50% of the US population undergoes screening,6 in contrast to screenings for breast and cervical cancer which are utilized by a high percentage of women.7-8 Inadequate screening for colon cancer is even more pronounced in minority communities such as Harlem, NY, where the 5-year survival rate of CRC patients is 20%9 compared with the national average of 47-62%.10 The decline in CRC mortality seen in white males and females has not been found among African Americans. Increasing CRCS, particularly in minority communities, is a major healthcare concern.

Certain obstacles particular to medically underserved communities prevent minorities from obtaining adequate health care and appropriate cancer screening. Those obstacles include lack of medical insurance, under-representation in the health care field, distrust of or poor satisfaction with the healthcare system, and inadequate infrastructure. For Hispanics who speak primarily Spanish, poor communication is another factor in making health care inaccessible.

While women in general are more likely to participate in preventive healthcare, CRCS is still suboptimal in this group and far below the screening rates for cervical and breast cancer. More than 90% of American women have had a Pap test, and 85% of women age ≥ 40 have had a mammogram.7 A random survey of New York's Harlem households from 1992-1994 showed that 80% of women age 50 to 65 have had a mammogram.8 In spite of the fact that many minority women lack primary care and medical insurance, they do go to screening mammography centers, driven by word of mouth recommendations or promotions through media announcements. In some of these centers, mammography is offered without charge.

This study examined the feasibility of offering CRCS to women at the time of mammography, thus eliminating the need for referral by a clinic or a physician, and thereby removing a major barrier to CRCS. In this way, we hoped to identify the barriers to screening and the ways to overcome them, and also to determine the prevalence, stage, and pathology of lesions found during screening. We hypothesized that mammography centers offered a unique opportunity to introduce the concept of colorectal cancer screening at the time of mammography or Pap smear. The women being tested would already be familiar with the concept of cancer screening, and we hypothesized that a substantial proportion would undergo colorectal cancer screening if they were made aware of its importance and if a mechanism existed to facilitate it.

A recent meta-analysis11 of interventions to promote screening mammography in populations with historically low rates of screening demonstrates that individualized, directed strategies (ie, one-to-one counseling) in a healthcare setting resulted in a significant increase in utilization. Similar findings were reported in CRCS.12 Future programs must be designed in the context of this medical environment in order to enhance the participation of minorities in CRCS.

Methods

Patients

The study was offered to women attending the Breast Examination Center of Harlem (BECH). This clinic, part of a community outreach program of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, offers free screening for breast and cervical cancer to women from the Harlem Community in New York City. A program to facilitate CRCS was implemented at BECH 2 years prior to the beginning of this study. Participation in our study was offered to all eligible women seen during the study period from July 2003 through October 2005.

Eligibility

To be eligible, participants had to be ≥ 50 years of age with no history of colorectal cancer or CRCS. History of CRCS was defined as fecal occult blood testing annually for at least the last 3 years, or colonoscopy within the last 10 years. Women with a serious illness which precluded a colonoscopy (severe heart or pulmonary disease, uncontrolled diabetes, or uncontrolled hypertension) were excluded from the study. Since the study participants required a telephone contact, those without such a contact were excluded. Telephone contact could be either through a participant's own telephone, a work telephone, or a close neighbor or relative.

Eligible women were given an initial explanation of the rationale for CRCS by a trained bilingual (English and Spanish) study assistant. Further explanation and consent were conducted by the nurse practitioner following the screening breast examination.

If an eligible woman chose not to participate in the study, the reasons for refusal were recorded anonymously. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards/Privacy Boards of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and North General Hospital.

Pre-Colonoscopy Evaluation

If a woman chose to participate in the study, a full explanation of the study was provided by the research assistant, and the woman was asked to sign a consent form. Explanation was given in Spanish if needed, and the consent form was also available in Spanish. Those who signed the consent completed a questionnaire (by themselves or with the assistance of the study assistant) to assess their attitudes, beliefs and barriers regarding colonoscopy screening. Then, an appointment was scheduled with a CRCS nurse practitioner (NP) for pre-colonoscopy medical evaluation and a general physical examination. At that same appointment, a detailed explanation covered the colonoscopy, preparation for the procedure, potential complications, and what to expect during and following the colonoscopy. Participants were also asked about family history of colon cancer. Blood was drawn for CBC, PT, PTT, and creatinine, unless results were available from 30 days prior to the appointment. Participants who were found to have active medical problems such as angina, heart failure, severe pulmonary problems, uncontrolled diabetes, or hypertension, were referred to a medical clinic or to their primary physician, and asked to return after treatment of the medical condition. An appointment for a colonoscopy was made for those participants who successfully completed pre-colonoscopy evaluation

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy was performed in a Harlem community hospital (North General Hospital) by 1 of 3 gastroenterologists. The gastroenterologist recorded the colonoscopy findings, early or late procedure-related complications, and the pathology findings, if applicable.

Participants were informed of their colonoscopy findings by the gastroenterologist after recovery from sedation, as is routine in clinical practice. Information on follow-up treatment (if necessary) or follow-up screening, and results of pathologic examination of lesions found during colonoscopy, were provided to participants by the CRCS nurse practitioner or gastroenterologist.

A telephone call was made to the participants within 6 weeks after colonoscopy. They were asked about any late procedure-related complications, and questioned about their satisfaction with the colonoscopy experience.

The reasons for noncompliance with the appointment for pre-colonoscopy medical evaluation or for colonoscopy were recorded through a telephone contact, when applicable.

Pathology

Pathology slides were initially reviewed by pathologists at the community hospital and subsequently by a specialist in gastrointestinal pathology. The GI pathologist was unaware of the initial pathology diagnosis. This was deemed necessary because of discrepancies that have been reported between community pathologists and GI pathologists in diagnosis of polyps.13

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, group means, and medians.

Results

From July 2003 through October 2005, all women age ≥ 50 attending BECH for screening mammograms were approached and invited to participate in this study. There were a total of 2616 women who were eligible, and of these 611 (23%) consented to participate, while 2005 (77%) declined (Figure).

Figure. Study Flow Chart.

Refusers

Because of limitations imposed by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA), only age and reasons for refusal were collected anonymously for the 2005 women who declined to participate in the study. The mean age was 58 years, range (44-91). Reasons for refusal included wanting to discuss CRCS with their primary physician (29%), wanting to have CRCS without participating in a study (22%), and lack of insurance (19%) (Table 1). Among all eligible women, only 5% cited lack of interest in CRCS, 7% cited fear and 1% cited lack of adequate knowledge as reasons for not wanting CRCS.

Table 1. Rationale for Refusing to Participate in the Study (n=2005).

| Reasons for Refusala | No. of Women (%)a |

|---|---|

| Wants to discuss with primary physician | 576 (29) |

| Wants CRCS but not part of a study | 437 (22) |

| Lack of insurance | 379 (19) |

| Needs time to think about it | 197 (10) |

| Already has CRCS appointment | 158 (8) |

| Fear of CRCS | 150 (7) |

| No interest in CRCS | 107 (5) |

| No time for CRCS | 100 (5) |

| Insurance not accepted at community hospital | 90 (4) |

| Lack of adequate knowledge | 21 (1) |

| Miscellaneous | 262 (13) |

Women could indicate multiple reasons for refusal.

Study Participants

The mean age of the 611 women who enrolled in our study was 56 years (range 47-84); 77% were <60 years of age. The racial composition was: 49% black non-Hispanic, 34% white Hispanic, 9% black Hispanic, and 8% others (Table 2). Two hundred thirty-three (38%) of the women spoke only Spanish, and 378 (62%) spoke English.

Table 2. Characteristics of Study Participants (N=611) According to Colonoscopy vs No Colonoscopy.

| Characteristics | Total on Study N=611 | Underwent Colonoscopy n=337 | No Colonoscopy n=274 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (range) | 56 (47-84) | 56 (50-84) | 56 (47-82) |

| Race, no. (%) | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 301 (49) | 162 (48) | 139 (51) |

| White Hispanic | 208 (34) | 115 (34) | 93 (34) |

| Black Hispanic | 53 (9) | 27 (8) | 26 (9) |

| Other | 49 (8) | 33 (10) | 16 (6) |

Of the 611 women who initially joined the study, 397 (65%) attended the pre-colonoscopy medical evaluation appointment; 337 (85%) of these women went on to have screening colonoscopy and 60 (15%) did not. Reasons for failure to have colonoscopy among the 60 women were: medical issues/illness (13), financial/insurance issues (12), moved/traveling (9), had it done elsewhere (9), lost to follow-up (9), and fear of the procedure (8).

Findings from Pre-Colonoscopy Medical Evaluation

During pre-colonoscopy evaluations, nurses found the following gastrointestinal symptoms in 60 (15%) women: constipation (33), rectal bleeding (34), change in consistency of bowel movements (6), abdominal pain/persistent bloating for past 3 months (10), diarrhea (3), recent unintentional weight loss (1). Eleven women were referred to primary care doctors by the nurse practitioner because of medical issues that needed to be resolved prior to CRCS. These included uncontrolled hypertension (6), and miscellaneous reasons (5). Six of these women did not return for CRCS. Five women had their medical issue resolved and went on to have CRCS without complications.

Family History

Of the 397 women who attended pre-colonoscopy evaluation, 365 (92%) reported no family history of colon cancer, 30 (8%) reported a family history, and 2 (1%) women did not know their family history (Table 3). Table 3 also correlates colonoscopy compliance and noncompliance in relation to family history.

Table 3. Family History of Colorectal Cancer in Study Participants Related to Study Colonoscopy.

| CRC Personal History | Family History Obtained (n=397), No. (%) | Study Colonoscopy | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Compliance (n=337), No. (%) | Noncompliance (n=60), No. (%) | ||

| No family history of CRC | 365 (92) | 309 (92) | 56 (93) |

| Unknown | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1 (2) |

| Family history of CRC | 30 (8) | 27 (8) | 3 (5) |

| First-degree relative | 21 (5) | 19 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Father | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Sister | 4 | 4 | NA |

| Brother | 7 | 7 | NA |

| Second-degree relative | 17 (4) | 16 (5) | 1 (2) |

CRC, colorectal cancer

Medical Insurance

Insurance status of the women who entered the study can be found in Table 4. Almost half of the study participants had some form of health insurance. At the start of the study, there were no grants to pay for screening those who were uninsured. These women were still offered CRCS if they were willing to pay $50 for the pre-colonoscopy evaluation and $300 for colonoscopy. A total of 29 women paid $350 out of pocket for CRCS. As previously noted (Table 1), 379 women who were uninsured refused to participate in the study. Later in the study, grants were available from the American Cancer Society and philanthropic sources, and free CRCS was offered to 223 uninsured women, of whom 151 (68%) then had CRCS. Overall, philanthropic grants accounted for 45% of the payments for CRCS of women who initially refused colonoscopy because of lack of insurance.

Table 4. Insurance Status and Payments for Study Colonoscopy (n=337).

| Payment Type | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Insured, total | 157 (47) |

| Commercial insurance | 68 (20) |

| Medicaid/medicaid HMO | 55 (16) |

| Medicare/medicare HMO | 19 (6) |

| Union insurance | 15 (4) |

| Uninsured, total | 180 (53) |

| Philanthropic grant | 151 (45) |

| Self-pay | 29 (9) |

Colonoscopy Examination and Findings

Sedation was given with Versed and Demerol. In the 337 participants who had colonoscopy, the cecum was reached in 301 (89%) and the colon cleared in 294 (87%).

The colon was not cleared in 43 (13%) participants (endoscopists recorded multiple reasons): 17 were owing to poor bowel preparation, 30 to technical difficulties, and 3 to patient discomfort. Subsequently, 6 patients were instructed to have a repeat colonoscopy and 37 a barium enema. At 2 years, only 2 of these participants had a repeat colonoscopy; 19 had barium enema. None of these tests detected polyps or cancer.

There were no complications during colonoscopy. Of the 337 participants who had colonoscopy, 101 patients (30%) were found to have a total of 149 polyps (70 had 1 polyp; 19 had 2 polyps; 8 had 3 polyps; 3 had 4 polyps; and 1 patient had 5 polyps). Pathology findings are presented in Table 5. The polyps were histologically classified by general pathologists and by a gastrointestinal (GI) pathology specialist. The GI pathologist classified more polyps as adenomas compared with the general pathologists, but within the adenomas, the GI pathologist was less likely to classify the adenoma pathology as advanced compared with the community hospital general pathologists.

Table 5. Comparison of Colonoscopy Polyps as Determined by GI and General Pathologists (n=101).

| Polyp Characteristicse | GI pathologist, No. | General pathologist, No. |

|---|---|---|

| Overall total | 149 | 149 |

| Adenoma | 66 | 57 |

| Location | ||

| Right sideda | 37 | 34 |

| ≥ 1.0 cm | 7 | 7 |

| Advanced | 10 | 15 |

| Left sidedb | 29 | 23 |

| ≥ 1.0 cm | 7 | 7 |

| Advanced | 8 | 13 |

| Size ≥ 1.0 cm | 14 | 14 |

| Size (range) | (0.1-5.0) | (0.1–5.0) |

| Advancedc | 18 | 28 |

| Pathologyd | ||

| Tubular | 53 | 29 |

| Tubular-villous | 12 | 27 |

| Tubular-villous and high grade dysplasia | 1 | 1 |

| Non-adenoma | ||

| Total | 79 | 88 |

| Total non-neoplastic/non-hyperplastic | 25 | 16 |

| Total hyperplastic | 54 | 72 |

| ≥ 1.0 cm | 2 | 3 |

| Right sided | 13 | 17 |

| ≥ 1.0 cm right sided | 1 | 2 |

| Size (range) | (0.2–1.5) | (0.2–1.5) |

Right sided defined as: cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, transverse colon

Left sided defined as: splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum

Advanced defined as: ≥ 1.0 cm, or tubular-villous

No villous pathology found

Total number of lost polyps: 4

Patients Satisfaction with Colonoscopy

Information on patient experience and satisfaction with the CRCS was obtained from 313/337 women using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = moderate, 4 = a lot, 5 = extremely). The mean results were as follows: pain during the colonoscopy (1.79); discomfort during the colonoscopy (1.78); embarrassment during colonoscopy (1.21); pain after colonoscopy (1.23); bleeding after colonoscopy (1.03); inability to eat after colonoscopy (1.08); inability to perform normal activities (1.13). Based on their experience, 88% of the women reported that they would have a colonoscopy again if necessary, 95% would recommend it to family and/or friends, and 95% consider colonoscopy a good test to have.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the utility of introducing colonoscopy screening within the context of an active, on-going mammography screening program. The utility of this approach was determined by the participation rate for colonoscopy and the yield of neoplastic findings from colonoscopy in minority women with no prior colorectal cancer screening. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date with screening colonoscopy findings in minority women.

Of the 611 women who participated in this study, 92% were black or Hispanic. Many of these women were unlikely to undergo CRCS, given that most of them lacked medical insurance and access to routine medical care. Introducing them to CRCS through the mammography center and without a doctor's referral was effective. This approach is viable for similar women in the general population, since many women undergo mammography even in the absence of regular medical insurance.14 It is clear from these data that after a simple, short explanation of screening colonoscopy given by a nonprofessional (in this case a study assistant), women became interested in the procedure even in the absence of a doctor's referral.

Although only 611 of the 2616 women who were eligible (23%) consented to participate in the study, the overwhelming majority of women were interested in CRCS as shown in Table 1. Only 150 (7%) women cited lack of interest as a reason for declining CRCS. These data indicate that once the women's attention was captured and an adequate explanation was given (facilitated by explaining in Spanish to those who did not speak English), the overwhelming majority was interested in CRCS. Thus, offering CRCS at the time of mammography is an effective way of generating interest and initiating the process.

An important component of the program was the scheduling of subsequent appointments. Once a woman was interested in participating in the study and in having a screening colonoscopy, an appointment was made for her to see a nurse practitioner for pre-colonoscopy medical evaluation. This ensured that the next step in the process would be taken, limiting the potential for dropout. It also allowed the office assistant to follow-up with the women who did not come to their appointment. This navigator assistant helped women overcome barriers to scheduling and facilitated the process. A similar approach was used by Chen et al.12 However, in the Chen report, women were referred from primary care clinics, and it is not reported what percentage of those approached actually participated in CRCS. All patients in that report had medicaid insurance, and therefore comprised a different population than ours, with only 47% having any insurance and thus being less likely to undergo CRCS.

The medical clearance by a nurse practitioner was effective in identifying those who were not qualified for colonoscopy because of medical reasons. The lack of significant medical complications (cardiac or pulmonary complications, bleeding, perforation, need for hospitalization) during colonoscopy indicates that a pre procedure medical evaluation by a nurse practitioner may be adequate, although the sample size is small. The only time women encountered a physician in this CRCS study was at the time of colonoscopy. Adapting this model may facilitate CRCS among low socioeconomic groups, considering that they might not have a family physician or their physician may be too busy to deal with preventive medicine.

The most important barrier to CRCS by colonoscopy was lack of insurance. Of the 337 women who underwent colonoscopy, 57% lacked insurance. It is remarkable that 29 women (9%) paid the $350 out of pocket. The remaining 48% were able to have the procedure paid for by grants from the American Cancer Society and other philanthropic sources. This group of women, with keen interest in CRCS, could possibly have cheaper methods of CRCS, but were unikely to have colonoscopy outside of this study. This highlights the need to find alternative funding sources from government or private institutions. Such funding is common in breast cancer screening.14 Considering that the cost effectiveness of breast and colon cancer screening is comparable, formulating a funding strategy for CRCS for the uninsured similar to that utilized for breast cancer screening could make a difference in minority populations.

This study is unique in the sense that it included only women, 92% of whom were either black or Hispanic. Thirty percent of the women had polyps upon colonoscopy (15% had adenomas). These numbers are comparable to the findings by Schoenfeld et al 15 who found adenomatous polyps in 20% of women, although in that group, only 14% were black or Hispanic. Advanced adenomas were found in 7% of women in our study, again similar to Schoenfeld's findings.15 As was previously reported, the general pathologists in our study diagnosed more advanced adenomas than the specialist GI pathologist.

Attempts to enhance colorectal cancer screening in this population by media campaigns, provision of FOBT cards and others usually have not met with much success16-17. It appears that a comprehensive program is needed in medically underserved areas. Such a program needs to include not only the initial contact but also assistance in navigating through the various stages of the screening process.

Future programs designed in the context of this medical environment will enhance the participation of minorities in CRCS.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Carol Pearce, MFA, writer/editor with the MSKCC Department of Medicine, for editorial assistance.

Support: This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [NCI grant R21 CA100587]; and the American Cancer Society; ClinicalTrials.Gov Identifier: NCT00613873. The funding sources did not have any role in the study except to provide the funding.

Footnotes

Disclosures: There are No financial disclosures to report from any of the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Bond JH, et al. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group 380. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:162–169. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, et al. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(3):169–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:555–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijan S, Hwang EW, Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Which colon cancer screening test? A comparison of costs, effectiveness, and compliance. Am J Med. 2001;111:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00977-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Increased use of colorectal cancer tests – United States, 2002 and 2004. MMWR. 2006;55(11):308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackman DK, Bennett EM, Miller DS. Trends in self-reported use of mammograms (1989-1997) and Papanicolau tests (1991-1997)—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. MMWR. 1999;48(SS-6):1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fullilove RE, Fullilove MT, Northridge ME, et al. Risk factors for excess mortality in Harlem. Findings from the Harlem Household Survey. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3S):22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freeman HP, Alshafie TA. Colorectal carcinoma in poor blacks. Cancer. 2002;94:2327–2332. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1973-1998 Colon and Rectum. www.seer.cancer.gov/publications.

- 11.Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, et al. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Jan;11(1):59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastro Hepato. 2008;6:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex D, Alikhan M, Cummings O, Ulbright T. Accuracy of pathologic interpretations of colorectal polyps by general pathologists in community practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:468–474. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tangka FKL, Dalaker J, Chattopadhyay SK, et al. Meeting the mammography screening needs of underserved women: the performance of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program in 2002-2003 (United States) Cancer Causes and Control. 2006;17:1145–154. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0058-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Flood A, et al. Colonoscopic screening of average-risk women for colorectal neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2061–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Nat Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1406–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz ML, Tatum CM, Dickinson SL, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1602–1610. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]