Abstract

Background

Students spend a large portion of their day in classrooms which may be a source of mold exposure. We examined the diversity and concentrations of molds in inner-city schools and described differences between classrooms within the same school.

Methods

Classroom airborne mold spores, collected over a 2 day period, were measured twice during the school year by direct microscopy.

Results

There were 180 classroom air samples collected from 12 schools. Mold was present in 100% of classrooms. Classrooms within the same school had differing mold levels and mold diversity scores. The total mold per classroom was 176.6 ± 4.2 spores/m3 (geometric mean ± standard deviation) and ranged from 11.2 to 16,288.5 spores/m3. Mold diversity scores for classroom samples ranged from 1 to 19 (7.7 ± 3.5). The classroom accounted for the majority of variance (62%) in the total mold count, and for the majority of variance (56%) in the mold diversity score versus the school. The species with the highest concentrations and found most commonly included Cladosporium (29.3 ± 4.2 spores/m3), Penicillium/Aspergillus (15.0 ± 5.4 spores/m3), smut spores (12.6 ± 4.0 spores/m3), and basidiospores (6.6 ± 7.1 spores/m3).

Conclusions

Our study found that the school is a source of mold exposure, but particularly the classroom microenvironment varies in quantity of spores and species among classrooms within the same school. We also verified that visible mold may be a predictor for higher mold spore counts. Further studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of mold exposure relative to asthma morbidity in sensitized and non-sensitized asthmatic children.

Keywords: Asthma, children, fungus, inner-city, mold, school

INTRODUCTION

Mold spores are ubiquitous in the indoor and outdoor environment. They play an important role in nature through the recycling of organic matter into useful nutrients. Mold spores are also responsible for a number of health related diseases as they can be allergens, irritants, infectious agents, or produce toxins. Several studies have suggested that mold sensitization is associated with asthma development and asthma morbidity.1–10 Additionally, a smaller literature links exposure to elevated mold pathogens such as mycotoxins or microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOC) to wheezing, development of asthma and increased asthma morbidity in non-sensitized children with asthma.11–17

The majority of indoor studies of mold have focused on the home environment or on “sick buildings” (e.g., the work environment). Few have provided detailed assessments of school or classroom exposures; however, the school/classroom environment potentially plays an important role in mold exposure, since children spend a large portion of their day in school. We measured the concentrations of airborne molds during two seasons inside 12 inner city elementary schools in the Northeast United States. The objective of this study was to examine the diversity, concentrations and presence of molds in these schools; to describe the differences between schools and classrooms; and to evaluate seasonal trends and predictors of total mold levels.

METHODS

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded School Inner City Asthma Study (SICAS) (R01AI073964) is an ongoing longitudinal study whose primary purpose is to evaluate the role of indoor allergens specific to the inner-city classroom environment and asthma morbidity in 400 students from 40 inner-city elementary schools. Recruitment is ongoing. The study design has been previously reported.18 Briefly, children with physician diagnosed asthma attending inner city schools were recruited from screening surveys collected during the spring and phenotypically characterized at baseline in the summer. The enrolled students were then followed longitudinally for asthma morbidity outcomes during the subsequent academic school year while school and home environmental exposure assessments were made. With permission from the school superintendent, settled classroom dust and air sampling for environmental allergens were collected twice during the academic school year and linked to the enrolled students with asthma. Only classrooms of asthmatic children who were part of this study were sampled. Every year a unique group of students are recruited from 5–7 different urban, elementary schools. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Boston Children’s Hospital and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Mold air sampling

Airborne mold spores were collected in each classroom using Burkard Indoor Recording Air Samplers (Burkard Mfg. Co., Rickmansworth, Herts., U.K.). Samplers were placed on the floor, in the periphery of the room and away from entryways or operable windows.

Slides were microscopically analyzed at 1000X magnification. A segment of the slide representing the school day (8:00 am until 4:00 pm) was marked, a portion of which was scanned, and all mold spores encountered were identified and counted. Raw counts were converted to airborne concentrations using the sampler flow rate, exposure time, and percent of the collection surface analyzed. Results were reported as spores per cubic meter of air (spores/m3) for the 8-hour collection period.18, 19 Two consecutive 8hour collection days were averaged for each classroom.

Mold analysis

A “total mold” category was calculated as the sum of all mold groupings. Individual mold groupings were reported and “unidentifiable” was used to categorize spores that were not morphologically identifiable but also a few rarely encountered types that did not fit into the following groupings. Penicillium and Aspergillus were reported together as they are usually too similar morphologically to differentiate by direct microscopy. Although basidiospores are discussed as a group in the results, to categorize mold groups and determine mold diversity scores, they were separated into four categories: small hyaline basidiospores, Coprinus, Ganoderma and other basidiospores. Likewise, ascospores were separated into Chaetomium, Leptosphaeria, Xylariaceae, Diatrype-like and Paraphaeosphaeria michotii, and “other ascospores”. Hyphal fragments were not included in the “total fungus” calculation but were reported as a separate fungal category.

Seasonal analysis

As previously described, classrooms were sampled twice annually, in the Fall and Spring, during the academic school year with approximately 6 months between sample collections.18

Mold diversity

For assessment of mold diversity, a score was generated for each classroom sample by summing the number of mold groupings present (excluding total mold, hyphae and unidentifiable spores). This score could range from 1 to 28. A score of 1 indicated only one mold grouping detected, where as a score >1 indicated multiple mold groupings detected.

Home and classroom environment dust sampling

The major scope and funding for this study was focused on the school environment. We did not have airborne mold spore sampling in the students’ homes. To try to account for the home exposure, we did a small analysis of home and school dust samples. Alternaria alternata 1 (Alt a 1) was measured by Luminex microarray™ (Indoor Biotechnologies, Charlottesville, VA, USA) from vacuum dust samples collected from each SICAS students’ home (bedroom) and classroom. The lower limit of detection was 0.004µg/g. Evaluation of other mold species by vacuum dust was beyond the scope of this study, given that extensive mold air sampling was already being performed in the classrooms, and due to the known limitations of dust sample analysis for molds.20

Classroom and home survey for detection of mildew/dampness

Dampness was evaluated in the classroom and the home. Study staff evaluated classroom dampness in the Fall and Spring by observing for presence of mildew or water stains on the ceiling, walls or window. Mildew was defined as visible mold. Parental survey ascertained whether there was mildew present in the home in the past 12 months.

Statistical analysis

Analyses are based on the first two years of study data. Geometric means were calculated for each mold grouping and total mold. In order to account for a high frequency of zero values, as was the case where certain fungal groups were rarely recovered, a value of 1 spore/m3 was added to all concentrations and then subtracted from the calculated geometric mean.21 Mold levels were compared between rooms with and without mildew using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for the non-independence of two samples (i.e. Spring and Fall) coming from the same classroom. Comparisons of mold by season were made using paired t-tests. Mixed-effects linear regressions were used to determine the variance in molds that was attributable to the school and classroom levels. Comparisons for Alt a 1 were made using Fisher’s exact test (Fall only) and comparisons for dampness were made using GEE (Fall and Spring samples). Analyses were generated using STATA 12 (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.).

RESULTS

There were 180 classroom air samples collected from 12 schools (5 schools in year 1 and 7 schools in year 2). 92 air samples were collected from the Fall and 88 air samples from the Spring. 117 vacuum dust samples were collected from the SICAS students’ bedrooms. 195 vacuum dust samples were collected from the schools.

School and classroom variation

Table 1 reviews the demographics of the 12 schools including year of construction, number of classrooms sampled and geometric means of the total mold concentration per school. The year of construction ranged from 1904 to 1975. There was no relationship between total mold concentration and school age. There was wide variation in total mold spore concentrations across the 12 schools. The geometric mean ranged from 32.5 spores/m3 in school 6 to 545 spores/m3 in school 7.

Table 1.

School characteristics and mold spore levels

| Total mold |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School ID | Year Built | Classrooms sampled |

Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Min | Max |

| 1 | 1972 | 34 | 217.8 ± 2.7 | 22.5 | 2430.6 |

| 2 | 1922 | 13 | 114.6 ± 1.9 | 42.4 | 342.8 |

| 3 | 1959 | 33 | 498.1 ± 6.0 | 44.7 | 16,288.5 |

| 4 | 1904 | 12 | 332.4 ± 3.6 | 85.8 | 8762.7 |

| 5 | 1925 | 9 | 493.0 ± 1.5 | 281.5 | 996.1 |

| 6 | 1975 | 24 | 32.5 ± 1.7 | 11.2 | 98.7 |

| 7 | 1932 | 7 | 545.0 ± 3.4 | 132.4 | 5025.6 |

| 8 | 1924 | 2 | 158.6 ± 2.1 | 93.5 | 269.2 |

| 9 | 1905 | 13 | 131.1 ± 1.4 | 56.1 | 179.5 |

| 10 | 1963 | 16 | 72.9 ± 2.4 | 19.0 | 544.1 |

| 11 | 1972 | 4 | 319.0 ± 3.4 | 82.3 | 919.8 |

| 12 | 1975 | 13 | 130.0 ± 4.0 | 29.9 | 7067.3 |

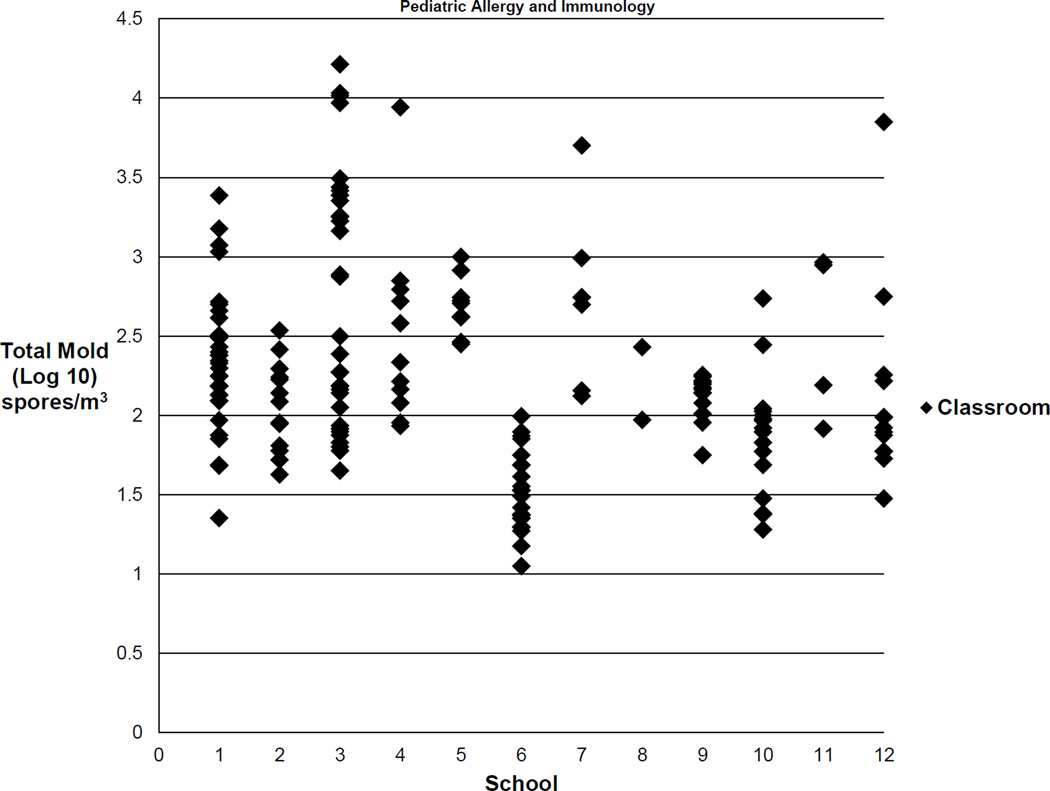

The number of samples collected per school ranged from 2 to 34 classroom samples. Figure 1 illustrates the wide variability in total mold quantity by classroom within each school. A mixed-effects model, which used season as a fixed effect, determined that the school level accounted for 38% of the variance in total mold quantity, leaving 62% of the variance attributable to the classroom level, thus demonstrating substantial variability between classrooms within the same school.

Fig. 1.

There is substantial variability in total mold quantity between classrooms within the same school. The values shown are the log 10 of the geometric means for total mold for each classroom.

Distribution of molds

The prevalence, quantity and range of 28 different mold groupings are summarized in Table 2. Mold was present in all classrooms (180 of 180). The most prevalent identifiable spores were Cladosporium, basidiospores, Penicillium/Aspergillus and smut spores.

Table 2.

Distribution of molds in classrooms (n =180)

| Mold Grouping | Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Detectable† | Min | Max | Percentiles | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th | 75th | |||||

| Total Mold | 176.6 ± 4.2 | 100% | 11.2 | 16,288.5 | 73.3 | 145.9 | 388.5 |

| Hypahe | 55.2 ± 2.8 | 98% | 0 | 555.4 | 33.7 | 59.9 | 92.4 |

| Unidentifiable spores | 31.2 ± 2.8 | 98% | 0 | 448.8 | 19.2 | 33.6 | 56.1 |

| Cladosporium | 29.3 ± 4.2 | 97% | 0 | 1,525.7 | 11.7 | 28.9 | 71.4 |

| Smut spores (Ustilaginomycetes) | 12.6 ± 4.0 | 89% | 0 | 639.4 | 7.5 | 15.0 | 34.0 |

| Penicillium/Aspergillus | 15.0 ± 5.4 | 88% | 0 | 8,586.0 | 4.0 | 15.0 | 46.7 |

| Other Basidiospores* | 6.6 ± 7.1 | 67% | 0 | 2,445.5 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 22.5 |

| Basidispores small hyaline* | 4.9 ± 9.6 | 54% | 0 | 11,173.1 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 11.3 |

| Other Ascospores | 2.7 ± 5.5 | 48% | 0 | 956.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.5 |

| Bispora | 1.1 ± 3.1 | 35% | 0 | 127.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Coprinus* | 1.2 ± 3.6 | 32% | 0 | 149.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Myxomycetes | 0.7 ± 2.5 | 31% | 0 | 74.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Rust spores (Pucciniomycetes) | 0.7 ± 2.4 | 31% | 0 | 29.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Alternaria | 0.7 ± 2.5 | 29% | 0 | 37.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Ganoderma* | 0.9 ± 3.4 | 28% | 0 | 403.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.8 |

| Other Mitospores | 0.5 ± 2.4 | 21% | 0 | 740.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Leptosphaeria# | 0.4 ± 2.2 | 17% | 0 | 53.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Curvularia | 0.4 ± 2.2 | 16% | 0 | 52.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bipolaris/Drechslera-like | 0.3 ± 1.9 | 13% | 0 | 29.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Xylariaceae# | 0.2 ± 1.9 | 12% | 0 | 59.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Pithomyces chartarum | 0.2 ± 1.8 | 12% | 0 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Chaetomium# | 0.2 ± 1.6 | 9% | 0 | 29.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Epicoccum nigrum | 0.2 ± 1.6 | 9% | 0 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Botrytis | 0.2 ± 1.8 | 8% | 0 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Diatrype-like# | 0.2 ± 2.0 | 8% | 0 | 82.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Stachybotrys | 0.1 ± 1.5 | 4% | 0 | 15.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Myrot hecium | 0.1 ± 1.6 | 4% | 0 | 29.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Scopulariopsis | 0.1 ± 1.6 | 4% | 0 | 55.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Torula | 0.03 ± 1.3 | 2% | 0 | 15.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Paraphaeosphaeria michotii# | 0.03 ± 1.2 | 2% | 0 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Periconia-like | 0.02 ± 1.2 | 1% | 0 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Detectable is defined as percentage of classrooms where a particular fungal type was identified at least once.

Basidiospore

Ascospore

The geometric mean of the total mold was 176.6 ± 4.2 spores/m3 ranging from 11.2 to 16,288.5 spores/m3 respectively. Of the identifiable spores, Cladosporium had the highest geometric mean of 29.3 ± 4.2 spores/m3. Also present in abundant quantities were basidiospores, Penicillium/Aspergillus, and smut spores.

Regarding the traditional “indoor molds” (those associated with dampness/moisture damage), Penicillium/Aspergillus was the most prevalent and found at the highest concentration (detected in 88% of samples, geometric mean of 15.0 ± 5.4 spores/m3). Bispora was detected in one third of classrooms. Chaetomium was infrequently recovered (9% of classrooms) and Scopulariopsis and Stachybotrys were rarely (4% of classrooms) recovered.

We defined a mold diversity score as the total number of mold types present in a classroom. The mold diversity score in the 180 classroom samples ranged from 1 to 19. On average, classrooms had approximately 7 mold groupings present (mean = 7.7, 25 to 75% of 5.0 to 10.0). A mixed-effects model demonstrated that the school level accounted for 44% of the variance in the number of mold groupings per sample, leaving 56% of the variance attributable to the classroom level, thus confirming substantial between classroom differences in mold diversity within the same school.

Classrooms with mildew

Table 3 reports the difference in mold spore concentrations in classrooms with mildew present versus those without. 27 (15%) classrooms were reported to have mildew on the ceiling, wall or window. Total mold spores and the most prevalent mold groupings were compared between classrooms. The means were consistently higher for rooms with mildew present and significantly higher for total mold, Cladosporium, basidiospores and Alternaria.

Table 3.

Comparison of molds in classroom with mildew† visualized vs. not visualized

| Mildew Visualized in Rooms (n=27) |

Mildew NOT Visualized in Rooms (n=139) |

P-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mold Grouping | Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Detectable | Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Detectable | |

| Total Mold | 305.6 ± 6.0 | 100% | 163.5 ± 3.9 | 100% | 0.03 |

| Cladosporium | 54.7 ± 5.2 | 100% | 26.4 ± 4.0 | 96% | 0.02 |

| Penicillium/Aspergillus | 19.0 ± 4.9 | 88% | 15.1 ± 5.3 | 89% | 0.56 |

| Other basidiospores | 23.7 ± 12.7 | 81% | 5.3 ± 6.0 | 65% | 0.001 |

| Basidispores small hyaline | 19.0 ± 18.2 | 77% | 4.0 ± 8.0 | 52% | 0.003 |

| Smut spores | 15.8 ± 3.8 | 89% | 11.7 ± 4.1 | 88% | 0.37 |

| Alternaria | 1.6 ± 3.3 | 46% | 0.6 ± 2.4 | 26% | 0.02 |

| Stachybotrys | 0.2 ± 1.8 | 12% | 0.1 ± 1.4 | 4% | 0.12 |

Mildew is defined as the presence of visible mold

two-sample t-test of log-transformed mold concentrations

Seasonal variation

Mold concentrations varied by season. This was estimated by comparing classrooms that had both a Fall and Spring sample (n = 80 for each season). Total mold and the most predominant mold groupings were compared and were significantly higher in the Fall as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of molds by season

| Fall (n = 80) |

Spring (n = 80) |

P-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mold Grouping | Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Detectable | Geomean ± Geostd (spores/m3) |

Detectable | |

| Total Mold | 252.0 ± 5.6 | 100% | 121.0 ± 3.0 | 100% | 0.004 |

| Cladosporium | 48.4 ± 5.0 | 98% | 17.2 ± 3.2 | 95% | <0.001 |

| Penicillium/Aspergillus | 22.0 ± 5.6 | 91% | 9.9 ± 5.4 | 83% | 0.002 |

| Other basidiospores | 13.2 ± 11.2 | 68% | 2.9 ± 3.3 | 65% | <0.001 |

| Basidispores small hyaline | 7.6 ± 14.5 | 54% | 3.1 ± 5.9 | 53% | 0.004 |

| Smut spores | 16.1 ± 5.0 | 86% | 9.5 ± 3.0 | 91% | 0.02 |

paired t-test of log-transformed mold concentrations

Home and classroom vacuum dust samples and dampness assessments

Assessments were made in the Spring and Fall. In the Spring, there were no positive dust samples for Alt a 1. In the Fall, Alt a 1 was detectable in more classroom samples, 9/100 (9%), as compared to home samples, 0/81 (p=0.005). Significantly more classrooms 27/180 (15%) reported signs of mildew as compared to homes, 4/138 (2.9%) (p=0.001).

DISCUSSION

Few published studies provide a comprehensive evaluation of airborne mold spores in classrooms.22–25 Our study, with a focus on the classrooms of asthmatic children from urban Northeast U.S. schools, is one of the largest to do so. We demonstrated that mold was found in all classrooms but there was a wide range in the quantity and diversity of mold present. Interestingly, classrooms within the same school had different mold levels and different mold diversity scores. Our data supports high and variable levels of classroom specific mold exposure, even within schools, suggesting classroom specific exposures may be important sources of allergen or irritant mold exposure.

There was a high degree of variance in the quantity and diversity of molds between classrooms in the same school. School 3 demonstrated that the total mold spore count varied from 44.7 spores/m3 in one classroom to 16,288.5 spores/m3 in another. The classroom accounted for the majority of variance (62%) in the total mold count and accounted for the majority of variance (56%) for the mold diversity score. These findings emphasize the importance of assessing the microenvironment. Classroom location, room shadiness versus sunlight, water incursions, high indoor humidity and temperature may all be contributing factors. The frequency for which windows are opened or structural abnormalities in the school and classroom may allow easier penetration of the outdoor air spores. The variability of these data underscore the importance of obtaining samples from multiple classrooms, because exposure seems to be classroom specific and obtaining a single school sample can potentially misclassify the exposure.

The predominant mold types recovered were Cladosporium, Aspergillus/Penicillium, and basidiospores, which are species generally known to cause symptoms in sensitized individuals. These findings are consistent with other studies that sampled indoor environments.22, 23, 26–29 Penicillium/Aspergillus were the most prevalent of the traditional “indoor” molds, found most consistently (in 88% of classrooms) and at the highest concentrations. In contrast, Alternaria was found in just 29% of rooms and not in high concentrations. Other molds that are commonly associated with indoor water damage or decay such as Stachybotrys, Chaetomium, Scopulariopsis, Bispora were found in low concentrations or were rarely recovered. Our data also showed a high concentration of hyphal fragments. Hyphae are filamentous, typically non-reproductive parts of the fungus that can share common antigens with spores.30 High concentrations of airborne hyphae can be an indication of unusually high fungal growth. Several studies have shown that these small fungal particles contribute to respiratory disease.31–33

Allergy testing is routinely done to check for sensitization to common molds. While some of the species found in the classrooms (Cladosporium, Aspergillus/Penicillium) are considered well known to be clinically important in sensitized individuals, some of the other less common classroom mold species for which there are no reliable or specific allergy tests may also have health effects. Although mold skin test extracts are largely non-standardized, it is possible that testing to other molds may help identify sensitized children who have increased asthma or rhinitis symptoms while at school.

We found that visualized mildew was a predictor of increased mold spore levels. As seen in Table 3, classrooms with visualized mildew had significantly higher levels of many of the common molds. The presence of mold spores indoors can either result from indoor moisture issues and/or from outdoor molds that have gained indoor access.34 Cladosporium, Alternaria and basidiospores are nearly ubiquitous in the outdoor air and often penetrate indoors. Some of these molds can proliferate further indoors under appropriate conditions. Additionally, leaking roofs, faulty plumbing, poor drainage or wet carpets may lead to focal areas of mold growth. However, it is well-acknowledged that there is no gold standard for measuring mold exposure and that visualization and measurements in the air and dust are complementary, but not necessarily tightly correlated.27

There was a seasonal relationship as the mold spore concentrations were higher earlier in the academic school year. Ambient spore counts reach a peak in the late Summer and Fall months and subsequently decrease with the frost.35 Our study had similar findings with increased spores during the Fall season when outdoor molds are often at a peak concentration in the Northeast. During these months there is a significant increase in decaying vegetation.

Some factors were not predictive of increased mold levels. School age did not correlate with total mold as mold was found in both new and older schools. Issues such as plumbing problems, leaky roof, malfunction in the ventilation system or poor structural integrity could be factors that are more likely affected by maintenance resources rather than school age.

A strength of this study is that our sampling methods utilized continuous air sampling through the entire school day which may reflect a more accurate exposure over long periods of time by averaging the short-term spore concentration peaks and troughs typically observed. We also used direct microscopy for identification and quantification of mold spores because it gave us the opportunity to report the most spore types, regardless of viability or culturability, and may give a measure of more clinically relevant molds than other methods.

We were limited in our ability to compare school versus home exposures to mold. We only measured airborne mold spores in the classrooms and not in the homes, but we do have measures of Alt a 1 from settled dust in both settings and we also ascertained reports of home dampness in the classrooms and the homes. Alt a 1 is not a highly prevalent mold indoors, but we did detect some Alt a 1 in classroom dust, whereas we detected no Alt a 1 in the homes of our participants. Dampness, a condition that can result in mold growth, was also reported more commonly in the classrooms compared to the homes. We have seen that urban housing in the Northeast U.S., specifically apartment housing, has heating that may be high in the winter. Warm dry air likely results in the low levels of dust mites we have measured previously in homes, and perhaps in the decreased dampness and absence of Alt a 1 that was measured in homes in this study.36 In contrast the urban classroom/school environment may be more likely to support the growth of a number of different molds and may be an important source of exposure for urban school children with asthma. Several studies have found that exposure to dampness or visible mold can be associated with wheezing or asthma development.11, 13, 14 The mechanism for this effects are not well defined.

Our study has limitations. First, the sampling resources were directed only at the primary classrooms of enrolled SICAS students. As such, some schools had a small number of classrooms sampled. However, we believe that the breadth of the sampling across many classrooms and several schools outweigh the limitations posed by having some schools potentially under-sampled. No outdoor sampling was available for comparison to further characterize sources of molds and predictive factors, thus our ability to directly relate indoor to outdoor mold concentrations is limited. However, our sampling was done during the academic school year in the Northeast, where conditions generally comprise of closed windows and limited exposure to outdoor molds. While some of the molds may have been carried in from outdoor sources, some of our highest concentrations included those molds more classically known as important in indoor environments, suggesting that there are likely direct indoor sources of mold in these classrooms.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates that the school/classroom environment can be a source of mold exposure both in quantity of spores and variety of mold types. In particular, we found that the classroom microenvironment varies among classrooms within the same school and that a classroom specific mold sampling may provide the most accurate exposure data. Our study also verified an intuitive belief that the presence of visible mold may be a predictor for high mold spore counts. Further studies are needed to determine the clinical significance of mold exposure relative to asthma morbidity in sensitized and non-sensitized asthmatic children.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants R01 AI 073964, R01 AI 073964-02S1, K24 AI 106822 and U10HL098102 (PI: Phipatanakul). This work was conducted with the support from Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award #UL1 RR 025758) and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbes SJ, Jr., Gergen PJ, Vaughn B, Zeldin DC. Asthma cases attributable to atopy: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1139–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denning DW, O’Driscoll BR, Hogaboam CM, Bowyer P, Niven RM. The link between fungi and severe asthma: a summary of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:615–626. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00074705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaakkola MS, Ieromnimon A, Jaakkola JJ. Are atopy and specific IgE to mites and molds important for adult asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:642–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Hollaren MT, Yunginger JW, Offord KP, Somers MJ, O’Connell EJ, Ballard DJ, et al. Exposure to an aeroallergen as a possible precipitating factor in respiratory arrest in young patients with asthma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:359–363. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvaggio J, Seabury J, Schoenhardt FA. New Orleans asthma. V. Relationship between Charity Hospital asthma admission rates, semiquantitative pollen and fungal spore counts, and total particulate aerometric sampling data. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1971;48:96–114. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(71)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targonski PV, Persky VW, Ramekrishnan V. Effect of environmental molds on risk of death from asthma during the pollen season. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:955–961. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush RK, Prochnau JJ. Alternaria-induced asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delfino RJ, Coate BD, Zeiger RS, Seltzer JM, Street DH, Koutrakis P. Daily asthma severity in relation to personal ozone exposure and outdoor fungal spores. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:633–641. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perzanowski MS, Sporik R, Squillace SP, Gelber LE, Call R, Carter M, et al. Association of sensitization to Alternaria allergens with asthma among school-age children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:626–632. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salo PM, Arbes SJ, Jr, Sever M, Jaramillo R, Cohn RD, London SJ, et al. Exposure to Alternaria alternata in US homes is associated with asthma symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:892–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bundy KW, Gent JF, Beckett W, Bracken MB, Belanger K, Triche E, et al. Household airborne Penicillium associated with peak expiratory flow variability in asthmatic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;103:26–30. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harley KG, Macher JM, Lipsett M, Duramad P, Holland NT, Prager SS, et al. Fungi and pollen exposure in the first months of life and risk of early childhood wheezing. Thorax. 2009;64:353–358. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iossifova YY, Reponen T, Ryan PH, Levin L, Bernstein DI, Lockey JE, et al. Mold exposure during infancy as a predictor of potential asthma development. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:131–137. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karvonen AM, Hyvarinen A, Roponen M, Hoffmann M, Korppi M, Remes S, et al. Confirmed moisture damage at home, respiratory symptoms and atopy in early life: a birth-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e329–e338. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reponen T, Lockey J, Bernstein DI, Vesper SJ, Levin L, Khurana Hershey GK, et al. Infant origins of childhood asthma associated with specific molds. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.030. e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flamant-Hulin M, Annesi-Maesano I, Caillaud D. Relationships between molds and asthma suggesting non-allergic mechanisms. A rural-urban comparison. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24:345–351. doi: 10.1111/pai.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai GH, Hashim JH, Hashim Z, Ali F, Bloom E, Larsson L, et al. Fungal DNA, allergens, mycotoxins and associations with asthmatic symptoms among pupils in schools from Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:290–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phipatanakul W, Bailey A, Hoffman EB, Sheehan WJ, Lane JP, Baxi S, et al. The school inner-city asthma study: design, methods, and lessons learned. J Asthma. 2011;48:1007–1014. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.624235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muilenberg ML. Sampling devices. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2003;23:337–355. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8561(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vailes L, Sridhara S, Cromwell O, Weber B, Breitenbach M, Chapman M. Quantitation of the major fungal allergens, Alt a 1 and Asp f 1, in commercial allergenic products. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:641–646. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eudey LSH, Burge HA. Biostatistics and Bioaerosols. In: HA Burge., editor. Bioaerosols. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc.; 1995. pp. 269–307. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levetin E, Shaughnessy R, Fisher E, Ligman B, Harrison J, Brennan T. Indoor air qualilty in schools: exposure to fungal allergens. Aerobiologia. 1995;11:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meklin T, Potus T, Pekkanen J, Hyvarinen A, Hirvonen MR, Nevalainen A. Effects of moisture-damage repairs on microbial exposure and symptoms in schoolchildren. Indoor Air. 2005;10(15 Suppl):40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoni M, Cai GH, Norback D, Annesi-Maesano I, Lavaud F, Sigsgaard T, et al. Total viable molds and fungal DNA in classrooms and association with respiratory health and pulmonary function of European schoolchildren. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 22:843–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taskinen T, Hyvarinen A, Meklin T, Husman T, Nevalainen A, Korppi M. Asthma and respiratory infections in school children with special reference to moisture and mold problems in the school. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:1373–1379. doi: 10.1080/080352599750030112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaumont F, Kauffman HF, van der Mark TH, Sluiter HJ, de Vries K. Volumetric aerobiological survey of conidial fungi in the North-East Netherlands. I. Seasonal patterns and the influence of metereological variables. Allergy. 1985;40:173–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1985.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chew GL, Rogers C, Burge HA, Muilenberg ML, Gold DR. Dustborne and airborne fungal propagules represent a different spectrum of fungi with differing relations to home characteristics. Allergy. 2003;58:13–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chew GL, Wilson J, Rabito FA, Grimsley F, Iqbal S, Reponen T, et al. Mold and endotoxin levels in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: a pilot project of homes in New Orleans undergoing renovation. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1883–1889. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor GT, Walter M, Mitchell H, Kattan M, Morgan WJ, Gruchalla RS, et al. Airborne fungi in the homes of children with asthma in low-income urban communities: The Inner-City Asthma Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorny RL, Reponen T, Willeke K, Schmechel D, Robine E, Boissier M, et al. Fungal fragments as indoor air biocontaminants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:3522–3531. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.7.3522-3531.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green BJ, Sercombe JK, Tovey ER. Fungal fragments and undocumented conidia function as new aeroallergen sources. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1043–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green BJ, Tovey ER, Sercombe JK, Blachere FM, Beezhold DH, Schmechel D. Airborne fungal fragments and allergenicity. Med Mycol. 2006;1(44 Suppl):S245–S255. doi: 10.1080/13693780600776308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reponen T, Seo SC, Grimsley F, Lee T, Crawford C, Grinshpun SA. Fungal Fragments in Moldy Houses: A Field Study in Homes in New Orleans and Southern Ohio. Atmos Environ. 2007;41:8140–8149. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horner WE, Helbling A, Salvaggio JE, Lehrer SB. Fungal allergens. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:161–179. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bush RK, Portnoy JM. The role and abatement of fungal allergens in allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:S430–S440. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.113669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitch BT, Chew G, Burge HA, Muilenberg ML, Weiss ST, Platts-Mills TA, et al. Socioeconomic predictors of high allergen levels in homes in the greater Boston area. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:301–307. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]