Abstract

This study examined the trajectories of delinquency among Puerto Rican children and adolescents in two cultural contexts. Relying on data from the Boricua Youth Study, a longitudinal study of children and youth from Bronx, New York, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, a group-based trajectory procedure estimated the number of delinquency trajectories, whether trajectories differed across contexts, and the relation of risk and protective factors to each. Five trajectories fit the Bronx sample, and four fit the San Juan sample. Differences and similarities were observed. The Bronx sample had a higher rate of delinquency and sensation seeking and violence exposure strongly discriminated offender trajectories. In San Juan, the results were substantively the same. Thus, while the youth lived in different contexts, and the nature and level of delinquency varied across the sites, the effects of most risk factors were more similar than different.

Keywords: delinquency, Hispanics, trajectories, longitudinal studies

Longitudinal studies of delinquency among children and adolescents provide an opportunity to examine the development of delinquency and to identify risk and protective factors associated with its progression or curtailment over time (Loeber and Farrington 1998). Several studies have shown that delinquency is associated with drug use, unsafe sex, and dangerous driving, among other mental health problems, across gender and ethnic groups (Brook and Whiteman 1997; Brook et al. 1998; Moffitt 2006; Moffitt et al. 1996; Piquero et al. 2007), and that differential rates of delinquency are predicted by child, familial, genetic, and environmental factors (Chung et al. 2002; Loeber and Farrington 2000; Moffitt et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2002). In particular, living in an urban environment characterized by neighborhood disorder, increased opportunity for drug use, weaker economic conditions, and fewer neighborhood resources has been associated with higher rates of delinquency (Arkes 2007; Crum, Lillie-Blanton, and Anthony 1996; Duncan, Duncan, and Strycker 2002; Elliott et al. 1996; Hill and Angel 2005; Karvonen and Rimpela 1997; Wilson et al. 2005).

Furthermore, ecological research has shown that many social problems are significantly clustered in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, racial heterogeneity, and family instability (Coulton et al. 1995; Duncan et al. 2002; Sampson 1992), of which African Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately residents (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). Evidence suggests that youth who live in socially disadvantaged and cultural contexts report higher rates of delinquent behaviors, exposure to violence, and neighborhood problems (Elliott et al. 1996), a finding that is magnified among minorities (Sampson and Wilson 1995). As such, urban minority youth are disproportionately at risk for maladaptive behavioral and emotional outcomes, drug use, and greater exposure to violence in their neighborhoods (McCord et al. 2001; Scheier, Botvin, and Miller 1999). Yet research on minorities with respect to these issues is scant.

Theoretically, there are several reasons for investigating whether the causal processes are invariant or variant across international contexts generally and with respect to race and ethnicity specifically. For example, it is important to understand the extent to which a common set of risk and protective factors identified in primarily and predominantly White, American-based samples replicate among Hispanics. This is important with respect to the extent to which general or racial, ethnic, and culturally specific theories of crime are warranted. On this score, Agnew’s (2001, 2006) general strain theory presents one specific hypothesis wherein strains are expected to vary across race, ethnicity, and culture, which in turn will generate unique adaptations with respect to crime and noncrime outcomes. Additionally, focusing on racial, ethnic, and cultural differences also affords the opportunity to pay specific attention to risk and protective factors that are uncommon in the more general, American-based delinquency research tradition. One of these factors in particular is the role of acculturation in relation to delinquency. Acculturation has a long theoretical tradition in psychology and sociology but not criminology, and thus we highlight this linkage to delinquency in the current study.

Thus, the goal of the present study was to place this empirical and theoretical backdrop within a specific cultural context and examine trajectories of delinquency among a subgroup of Hispanic youth (i.e., Puerto Rican children and adolescents) from two different cultural contexts (Bronx, New York, and San Juan, Puerto Rico), an ethnic group that has largely been underrepresented with respect to crime and criminal justice issues and research (Morenoff 2005). We further investigated how a series of risk and protective factors related to delinquency trajectories in an effort to examine whether the same set of factors distinguished offender trajectories and whether these factors were associated with delinquency differently across the two cultural contexts.

Evaluating trajectories of delinquency over time is an important step toward distinguishing offender trajectories and examining the progression of delinquency among children and adolescents. In contrast to cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies permit the investigation of the nature and progression of delinquency over time, and several predominantly White, American-based delinquency studies have indicated a general aggregate decline across time (age) in self-reported delinquency (Piquero, Farrington, and Blumstein 2003). Instead of an aggregate portrait, a group-based methodological framework provides the opportunity to study how criminal activity changes over time by investigating whether there are different groups of offenders, whether their trajectories exhibit different shapes at different developmental stages (e.g., childhood, adolescence, adulthood), and the influence of personal, familial, social, and environmental factors on the development of delinquent behaviors over time. Piquero (2008) reviewed the literature on developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course and summarized the findings of over 80 studies examining trajectories of criminal activity among children and adolescents with two statements. First, by the end of adolescence, most trajectories of criminal activity show a decline (regardless of the outcome being assessed). Research shows an adolescent-peaked pattern, a chronic offending pattern (which declines in most studies), and a late-onset chronic pattern (a youth begins offending in middle and late adolescence and continues offending at a steady rate into adulthood). Second, the number of trajectories has been consistent across different studies, between three to five groups, independent of the methodologies used to measure criminal activity.

When examining trajectories of delinquency among children and adolescents, three considerations need further research: (1) examining whether different trajectories of delinquency exist across ethnic and minority youth, (2) modeling delinquency behaviors (which differ from antisocial and externalizing behaviors), and (3) investigating how risk and protective factors (e.g., personal characteristics, familial, peer, environmental) relate to the development and progression of delinquency over time. First, although the role of individual characteristics, such as gender, in the patterns of offending trajectories has been investigated (D’Unger, Land, and McCall 2002; Piquero, Brame, and Moffitt 2005), few offending trajectory studies have included minority youth. Furthermore, there is a complete lack of data on Hispanic offending in the larger criminological literature generally, and whether distinct offending trajectories among Hispanic youth appear as they do for White and Black youth in particular (Piquero 2008). Therefore, there is a need to examine developmental trajectories of delinquency among distinct subgroups of minority populations. Second, many studies, especially among youthful populations, have examined externalizing and antisocial behaviors rather than delinquent behaviors. Externalizing behaviors include conduct problems, physical aggression, oppositional behavior, hyperactivity, and delinquent peer affiliation, among others. These behaviors, however, do not always include delinquency. As a result, there is a need to investigate developmental processes of trajectories of delinquency among children and adolescents. Third, few studies have examined risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of delinquency among children and adolescents (Piquero 2008). Furthermore, of the studies to examine such risk and protective factors, none have used Hispanic children and adolescents.

Before we proceed, it is instructive to provide some theoretical explanation for (1) how and why different trajectories might exist for the two Hispanic populations, (2) how and why risk factors might differ across the trajectories and populations, and (3) how and why ecological context (e.g., Bronx vs. San Juan) may (or may not) condition these relationships.

Different trajectories might exist across the two samples for several reasons. First, a recent overview of over 80 trajectory studies indicated that the number of trajectories identified varied according to the sample composition, age range, and types and measures of delinquency and crime (Piquero 2008). Thus, because of the distinctive samples alone, different trajectories may be observed. Second, and more important, the samples themselves are quite distinct, one reared in the United States and the other in Puerto Rico. Within these locales, the samples were also drawn from unique and distinct ecological contexts that likely influence individual and familial behaviors and activities. These two (and likely several other) reasons provide impetus for an inquiry into offending trajectories.

The risk factors may differ across the trajectories because (1) Black and Hispanic children living in the United States are exposed to some unique risk factors that White children are not exposed to; (2) some risk factors, especially poverty and residence in disadvantaged communities, may be found at higher levels among Black and Hispanic children; (3) risk factors may have longer duration and/or have interactive effects among Black and Hispanic children; and (4) protective factors may be less common among Black and Hispanic children (Farrington, Loeber, and Stouthamer-Loeber 2003; McCord et al. 2001). With respect to the first reason, the role of acculturation has been identified as an important correlate of adjustment generally (and thus, by extension, delinquency) among Hispanic children, but it is not a central delinquency correlate for Whites and likely Blacks (especially those who were born in the United States).

With regard to the second through fourth reasons, Farrington et al. (2003) examined reports of violence among Whites and Blacks (no Hispanics were available in the Pittsburgh Youth Study data) and found that predictors of violence included Black race, poverty and single-parent families, young maternal age, physical punishment, a bad neighborhood, and poor school achievement. Moreover, even after controlling for the various risk factors, the relationship between race and violence was reduced but not eliminated. Additionally, Piquero, Moffitt, and Lawton (2005) used data from the Baltimore Perinatal Project and found that although similar risk factors were related to chronic offending among Whites and Blacks, Blacks had higher levels of the risk factors than Whites. Finally, McCord et al. (2001) noted that compared with Whites, Blacks (and to a somewhat lesser extent Hispanics) are subject to higher rates of poverty and lengthy residence in disadvantaged environments, both of which have been found to be related to offending. In a related and interesting study, Bridges and Steen (1998) examined probation officers’ attributions about the causes of crime committed by White and Black youth and found that for the latter, crime was attributed to negative attitudinal traits and personality defects, whereas among the former, crimes were believed to be caused by external environmental factors (e.g., family dysfunction, drug abuse, negative peer influence). To the extent that empirically based research on the causes of crime can be used to verify such perceptions, it would be interesting and likely relevant with respect to theoretical modification, extension, and development.

Finally, the ecological context may condition these relationships, because the Bronx and San Juan samples were drawn from decidedly distinct ecological contexts. Although there were observable differences in income between the sites insofar as the percentage of households receiving welfare or public assistance (46 percent in the Bronx sample and 36 percent in the San Juan sample, t = 4.76, p < .001), poverty may not have the same effect in both contexts, because roughly half of the population in Puerto Rico is poor (48 percent, according to the 2000 U.S. census), compared with a much smaller percentage of the population in the United States who are considered at or below the poverty level. Moreover, one important contextual difference between the sites is that on the mainland, Puerto Rican children are a minority and often subject to discrimination because of their skin color or ethnicity, whereas the youth on the island do not experience this kind of prejudice, given that they are the majority.

Another potential contextual difference is that in Puerto Rico, teachers will likely be of the same ethnic and cultural group as their students and also speak their language, facilitating communication and interaction, but the same is not true in the United States. In addition, students are not expected to experience discrimination at school from other students on the island, but this is more likely to happen in the United States. The fact that Puerto Rican youth socialized in the United States experience these ethnic-specific stressors (i.e., prejudice and discrimination) that are unique to their sociocultural experiences is likely to undermine their psychological well-being, with delinquency being a possible outcome of this frustration. Agnew (2001, 2006) recently identified prejudice and discrimination as key sources of strain in general strain theory. Similarly, a long line of research has demonstrated Hispanic Americans’ vulnerability to adverse behavioral outcomes, including delinquency, as a result of the stress they experience in having to confront acculturative strains, such as the weakening of strong supportive family networks, adapting to a foreign language and culture, experiencing conflict with parents, and facing discrimination in the classroom (see Berry 1980; Cervantes and Castro 1985; Padilla 1980; Pérez, Jennings, and Gover 2008; Rodriguez and Zayas 1990; Smart and Smart 1995). Thus, Puerto Rican youth reared in the United States may be at a greater risk for delinquency compared with their native Puerto Rican counterparts because of their susceptibility to these daily undesirable life circumstances.

Current Focus

In the present study, we examine trajectories of delinquency among Puerto Rican children and adolescents (aged 5 to 13 years) from two different cultural contexts (the Bronx and San Juan). The BoricuaYouth Study (BYS; Bird, Canino, et al. 2006; Bird, Davies, et al. 2006) implemented identical methodological protocols to examine children and youth from these two cultural contexts across three waves of data. The BYS is the first child and adolescent psychiatric epidemiological study that permits comparisons of ethnic minority individuals from the same ethnic group (in this case Puerto Ricans) living in the United States and those living in their country of origin (Bird, Canino, et al. 2006; Bird, Davies, et al. 2006).

Studies have shown that the rates of antisocial behavior, drug use, and other conduct disorder problems are higher among youth in the United States compared with youth in Puerto Rico (Bird, Canino, et al. 2006; Bird, Davies, et al. 2006; Canino et al. 2004). In the present study, we used a group-based trajectory procedure to empirically identify the number of delinquency trajectories among Puerto Rican children and adolescents living in two different cultural contexts, permitting the comparison of trajectories of delinquency among these populations, and examined risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of delinquency across two sites.

Three research questions were addressed: (1) How many distinct patterns of delinquency best represent the heterogeneity in delinquency among Hispanic children and adolescents? (2) Are trajectories of delinquency different by cultural context (Bronx vs. San Juan)? and (3) How do trajectories of delinquency vary across risk and protective factors? On the basis of prior research, it was hypothesized that between three and five groups would adequately represent the heterogeneity in delinquency trajectories among Hispanic children and adolescents. Similarities in the number (but not necessarily the level) of trajectories of delinquency across cultural context were expected, but it was hypothesized that the relations of personal, familial, and environmental factors to the trajectories of delinquency might differ across Puerto Rican children and adolescents living in these two cultural contexts. Prior research has documented a higher number of risk factors in the Bronx than in San Juan such as behavior disruptive disorders and antisocial behavior (Bird, Canino, et al. 2006; Bird, Davies, et al. 2006; Bird et al. 2007).

Methods

Data

Data for this project came from two samples of youth participating in the BYS (Bird, Canino, et al. 2006; Bird, Davies, et al. 2006), a longitudinal study of children initially aged 5 to 13 years drawn from two sites: one in the standard metropolitan areas of San Juan and Caguas in Puerto Rico and the other in the South Bronx in New York City. Three assessments were carried out between summer 2000 and fall 2004 (Bird et al. 2007). All interviews were conducted one year from the last interview. Therefore, all interviews were performed within the same time frame (one year). Data on the sex distribution of the participants indicate that the San Juan sample was 51.36 percent male, while the Bronx sample was 51.75 percent male. Overall, the mean ages of the youth across waves were 9.65 years (SD = 2.56 years) at wave 1, 10.62 years (SD = 2.58 years) at wave 2, and 11.56 years (SD = 2.56 years) at wave 3. The average age of the San Juan sample at wave 1 was 9.77 years (median = 9 years, with more than half being between ages 9 and 13), increasing to average ages of 10.72 and 11.74 years at waves 2 and 3, respectively, while the average age of the Bronx sample at wave 1 was 9.51 years (median = 10 years, with more than half being between ages 9 and 13), increasing to average ages of 10.49 and 11.33 years at waves 2 and 3, respectively. Although the San Juan youth were statistically although not substantively older than the Bronx youth at wave 1 (mean difference = 0.25 years, t = 2.55, p < .05), there was not a significant difference in the gender composition across sites (t = 0.19, p = .85).

In Puerto Rico, the sampling process yielded 1,526 eligible participants, of whom 1,353 were interviewed, for a completion rate of 88.7 percent at baseline, while in the South Bronx, 1,414 were eligible for inclusion in the study and 1,138 parent or caretaker dyads participated, for a completion rate of 80.5 percent at baseline (average =84.7 percent). Site-specific sample retention in the two yearly follow-ups was 85.6 percent or higher, specifically, 89.4 percent in the Bronx and 93.8 percent in San Juan at wave 2 and 85.6 percent in the Bronx and 89.7 percent in San Juan at wave 3 (see Bird et al. 2007). A test of the difference of proportions indicated that study retention rates were not significantly different across sites at either wave 2 (p = .221) or wave 3 (p = .233).

With respect to survey administration, Bird, Canino, et al. (2006) reported that interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes. To the extent possible, children and parents were interviewed simultaneously but separately and in private by different interviewers. Interviews were computer programmed in both English and Spanish and administered using laptop computers. Interview audiotapes were obtained for the purposes of quality control. The computerized protocol avoided missing data, inappropriate skips, and out-of-range codes and automatically carried out data entry. Missing data did not seem to be a problem (i.e., less than 2 percent among children aged 10 years or older and 3 to 4 percent among those aged 5 to 9 years). Additional details regarding the background, design, and survey methods related to the BYS may be found in Bird, Canino, et al. (2006) and Bird, Davies, et al. (2006).1

A few other descriptive data are worth highlighting. First, in general, there is significantly more delinquency in the Bronx than in San Juan, and the rates were significantly higher in the Bronx on average at each of the three waves (see Table 1). Second, regardless of site, there was, for the most part, a general aggregate decline across waves (over time and age) in self-reported delinquency, a finding that replicates the majority of American-based delinquency studies (Piquero et al. 2003). Third, as expected, across all three waves, male youth evinced significantly more delinquency.2 For example, the mean rates of delinquency across three waves for the Bronx male youth were 1.03, 0.77, and 0.70 respectively, significantly greater than the rates for Bronx female youth of 0.62 (t = 4.25, p < .001), 0.46 (t = 3.46, p < .001), and 0.41 (t = 2.75, p < .01). Similarly, the San Juan male youth’s rates of delinquency were significantly greater than the female youth’s rates at wave 1 (0.84 vs. 0.47, t = 3.70, p < .001), wave 2 (0.41 vs. 0.26, t = 2.99, p < .001), and wave 3 (0.36 vs. 0.22, t = 2.90, p < .001).

Table 1.

Boricua Youth Study Demographic Characteristics and Significant Group Differences at Baseline

| Bronx |

San Juan |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

| Gender | 1.48 | .50 | 1 | 2 | 1.49 | .50 | 1 | 2 |

| Attitudes toward delinquency | 3.22 | 4.82 | 0 | 47 | 3.28 | 6.50 | 0 | 54 |

| Sensation seekinga | 3.63 | 2.53 | 0 | 10 | 2.90 | 2.32 | 0 | 10 |

| Self esteema | 12.63 | 2.98 | 0 | 16 | 12.19 | 2.82 | 0 | 16 |

| Peer relationshipsa | 4.00 | 1.20 | 0 | 5 | 4.34 | 1.03 | 0 | 5 |

| Peer delinquency | .24 | .36 | 0 | 2 | .23 | .32 | 0 | 2 |

| Parent-child interactiona | .77 | .19 | 0 | 1 | .72 | .22 | 0 | 1 |

| Exposure to violence | 2.51 | 3.48 | 0 | 33 | 2.30 | 3.74 | 0 | 30 |

| Coercive discipline | .38 | .55 | 0 | 3 | .36 | .57 | 0 | 2.5 |

| Acculturationa | 3.61 | .63 | 1 | 5 | 1.92 | .63 | 1 | 5 |

| School environmenta | 3.30 | 3.05 | 0 | 14 | 2.46 | 2.75 | 0 | 14 |

| Social supporta | 1.86 | .49 | 0 | 3 | 2.04 | .47 | 0 | 3 |

| Locus control | .75 | .39 | 0 | 2 | .74 | .35 | 0 | 2 |

| Stressful life eventsa | .93 | 1.50 | 0 | 10 | 1.03 | 1.51 | 0 | 13 |

| Welfarea | .92 | 1.00 | 0 | 2 | .73 | .96 | 0 | 2 |

| Delinquency | ||||||||

| Wave la | .83 | 1.63 | 0 | 17 | .66 | 1.83 | 0 | 20 |

| Wave 2a | .62 | 1.44 | 0 | 14 | .34 | .91 | 0 | 9 |

| Wave 3a | .56 | 1.65 | 0 | 23 | .29 | .79 | 0 | 9 |

Significant differences (p < .05).

Variables

Dependent variable

For each of the three waves of data collection, a modified version of a common self-report delinquency measure was used across the two sites (Elliott, Huizinga, and Ageton 1985). Items measuring past-year delinquency were different across the age groups (ages 5 to 9 and age 10 and older). Representative items for both age groups included stealing or trying to steal anything; intentionally break, damage, or destroy something that did not belong to you; and taking something from a store that did not belong to you. Representative items for the older group included carrying a weapon, snatching someone’s purse or wallet or picking a pocket, throwing rocks or bottles at people, and so on. For the younger group, the delinquency scale contained 29 items, while for the older group, 36 items were included (see Table 2). Because each item was answered “no” or “yes,” we summarized the “yes” responses into a variety scale, on which higher scores represented a larger number of distinct items endorsed (Hindelang, Hirschi, and Weis 1981).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Delinquency Scale: Items by Age Group

| Ages 5 to 9 | Ages 10 and Older |

|---|---|

|

|

Note: All items except item 36 for those aged 10 years and older begin with “In the past year, have you ….”

We recognize that the measures of delinquency differed by age group, yet we retained the delinquency scales as originally developed in the BYS for two main reasons. First, we intended to remain as consistent as possible with other publications that have used the BYS delinquency scales, so that study findings regarding the BYS delinquency scales could be considered and compared across studies. Second, recognizing the potential issues that could emerge with using different items in the delinquency scale, we undertook a supplemental analysis in which we investigated the prevalence of cases for which the different delinquency scales were used over time. Although fewer than one in five youth were administered the different scales across waves because their developmental age progressed out of the specified range (i.e., from ages 5 to 9 to age 10 and older), only 16 of the BYS youth (fewer than 1 percent of the sample) actually had nonzero counts of delinquency across the three waves. Nevertheless, we removed these 16 youth from the sample and examined how or if the scales varied across the two samples and if the various covariates of interest were affected by removing these handful of youth. The results of this supplemental analysis indicated that the trajectory procedures and the group mean covariate levels were unaffected by the exclusion of the youth who were administered the different delinquency scales over time and reported delinquent involvement. In addition, the overall distribution of delinquency across waves and by site was virtually similar with or without these youth. Therefore, although we followed the BYS protocol in using the same delinquency scales in our analysis (which were developed with recognition that delinquency manifests itself over time), we recognize that the inclusion of a few items in one wave but not another may have exerted some small degree of influence on our analysis. At the same time, given that there were only a few cases (fewer than 1 percent) for which some of the delinquency items changed over time and the youth reported delinquency endorsements, we remain confident that the trajectory solutions emerging from our analysis are useful and important, especially given the paucity of such research on Hispanic adolescents in two different cultural contexts.

Independent variables

Following the extant literature on risk and protective factors, we also distinguished the ensuing trajectory groups according to several risk and protective factors at the first wave of data collection using the following variables: gender, attitudes toward delinquency, sensation seeking, self-esteem, peer relationships, peer delinquency, parent-child interaction, exposure to violence, coercive discipline, acculturation (of youth), school environment, social support, locus control, stressful life events, and welfare. Table 1 lists descriptive information for the variables for the Bronx and San Juan samples as well as indicating which risk and protective factors significantly differed across site. The Appendix contains further information on the study measures and provides the Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient for the each of the various measures as applicable. Recognizing that α represents a lower bound of reliability, we observed that a few of the scales showed somewhat low α reliability estimates. We retained these scales in the analyses for three reasons. First, the scales have been used in extant BYS-related research, and their use here provided a further point of comparison and analysis. Second, even with the somewhat low α values, the scales still operated as theoretically expected; that is, they related to delinquency as extant theory would predict, and they did in fact distinguish the offender trajectories (i.e., the higher delinquent trajectories showed more risk and less protection on the risk and protective factors, respectively). Still, it remains a possibility that the scales with low α values, which were originally developed for use with White samples, may not be as reliable for Hispanics.

Analytical Strategy

Mixture or group-based methods are often used to model unobserved heterogeneity in a population, and this is especially the case for delinquency, for which it is believed that there are subpopulations differing in their offending over the life course (Nagin 2005; Piquero 2008). We used the group-based procedure developed by Nagin and Land (1993) and programmed into the SAS software package by Jones, Nagin, and Roeder (2001). This procedure, referred to as PROC TRAJ, is available from the National Consortium on Violence Research (http://www.ncovr.org).

Because we were dealing with count data, the Poisson model is potentially appropriate here, but more zeros were present in the delinquency data than would be expected in the pure Poisson model, so we used the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model (Jones et al. 2001), which takes into consideration the overrepresentation of zero-cell counts in the data. Additionally, we note that the ZIP model corresponds to the intermittency parameter that Nagin and Land (1993) originally estimated. In short, it is important to point out that ZIP is essentially intermittency.

To evaluate model fit, we followed extant research and use the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The BIC, or the log likelihood evaluated at the maximum likelihood estimate less half the number of parameters in the model times the log of the sample size (Schwartz 1978), tends to favor more parsimonious models than likelihood ratio tests when used for model selection. For a given model, the BIC is calculated as follows:

where L is the value of the model’s maximized likelihood, N is the sample size, and k is the number of parameters in the model, which is determined by the order of the polynomial used to model each trajectory and the number of groups (Nagin 2005). We used an iterative procedure to identify meaningful groups. We began with a one-group model and continued along the modeling space to two, three, four, five, and six groups, until we maximized the BIC.3 We also examined trajectories using different types of polynomials (constant only, linear, quadratic, and cubic) to determine which approach best characterized offending in the BYS.4 Our approach is best characterized as descriptive: Are there unique offending trajectories in the two BYS sites (Bronx and San Juan)? If so, what do those trajectories look like, and do they differ across the two cultural contexts? And how do they vary according to key risk and protective factors? Collectively, these findings will speak to debates regarding the need for race- and ethnicity-specific theories of delinquency and crime over the life course.

Results

We conducted a search of all possible models within the class for k ≤ 6 and for four different polynomial orders (constant, linear, quadratic, and cubic). The linear model was the best fit for all models. A five-group linear model provided the best fit for the Bronx sample, while a four-group model was best for the San Juan sample.5

Posterior Probability Assignments

In Table 3, we present the maximum posterior membership probabilities for the Bronx and San Juan solutions. We follow the model’s ability to sort individuals into the trajectory groups to which they had the highest probability of belonging (the “maximum probability” procedure). On the basis of the model coefficient estimates, the probability of observing each individual’s longitudinal pattern of offending was computed conditional on his or her being, respectively, in each of the latent classes. The individual was assigned to the group to which he or she had the highest probability of belonging. This procedure, of course, does not guarantee perfect assignment (i.e., a posterior probability assignment equal to 1.0 for each individual). Nevertheless, the mean assignment probability for each group was relatively high, suggesting that the large majority of individual trajectories could be classified to particular group-based trajectories with high probability and that the model had relatively little ambiguity when making these assignments.6

Table 3.

Mean (median) Posterior Probabilities for Group Assignments

| Group | Prob(group 1) | Prob(group 2) | Prob(group 3) | Prob(group 4) | Prob(group 5) | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bronx sample | |||||||

| 1 (n = 559) | .81 (.84) | .18 (.15) | .01 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .84 | .84 |

| 2 (n = 424) | .10 (.02) | .81 (.80) | .06 (.01) | .03 (.00) | .00 (.00 | .68 | .94 |

| 3 (n = 92) | .00 (.00) | .10 (.04) | .86 (.92) | .02 (.00) | .02 (.00) | .75 | .99 |

| 4 (n = 48) | .00 (.00) | .11 (.06) | .05 (.01) | .80 (.85) | .04 (.00) | .67 | .98 |

| 5 (n = 15) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .08 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .92 (.99) | .96 | .99 |

| San Juan sample | |||||||

| 1 (n = 803) | .88 (.90) | .12 (.10) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .90 | .90 | |

| 2 (n = 472) | .12 (.00) | .84 (.95) | .04 (.01) | .00 (.00) | .60 | .95 | |

| 3 (n = 57) | .00 (.00) | .15 (.08) | .82 (.88) | .03 (.00) | .69 | .99 | |

| 4 (n = 21) | .00 (.00) | .02 (.00) | .04 (.00) | .94 (.99) | .90 | .99 |

Note: Minimum and maximum values are presented for the group-Prob(group) combinations.

Self-Reported Offending Trajectories

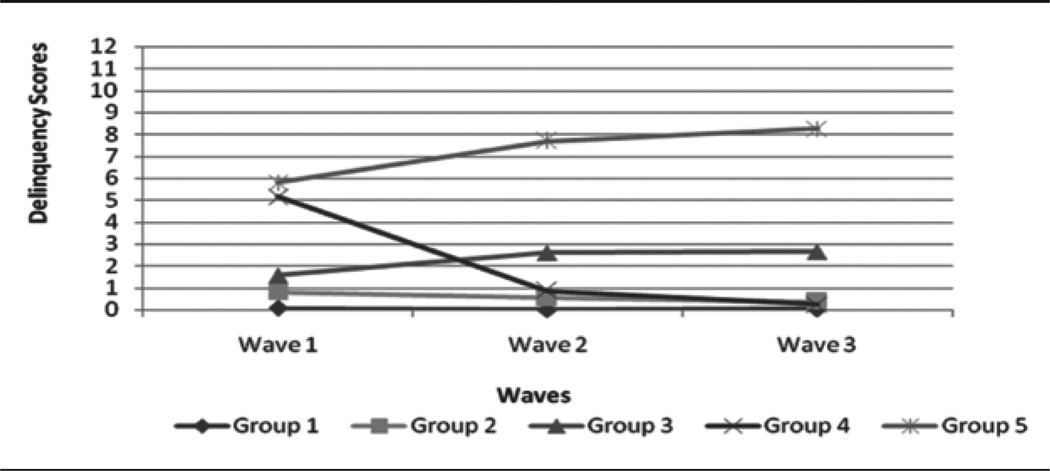

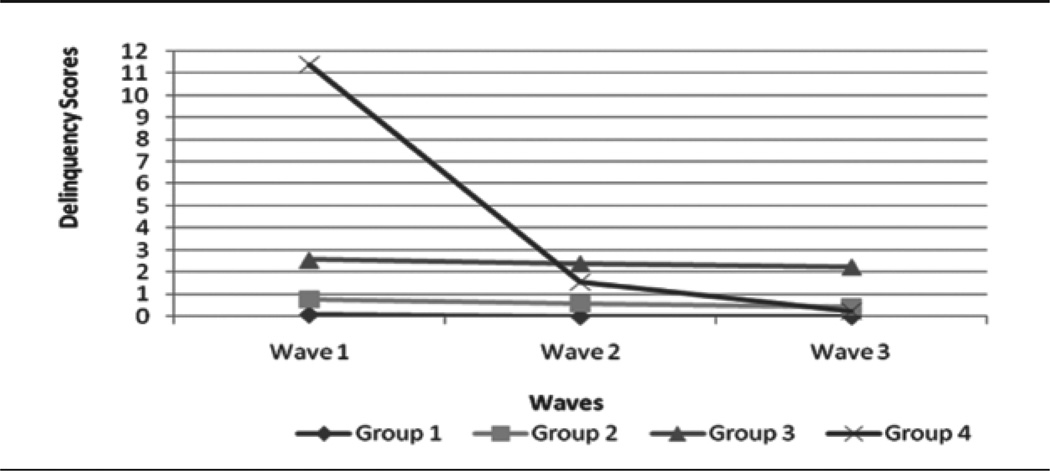

To aid in the substantive interpretation of the nature of the offending trajectories identified and estimated in the BYS, the predicted trajectories (i.e., predicted on the basis of estimated model parameters) for each of the trajectories implied by the model are presented for the Bronx (Figure 1) and San Juan (Figure 2) samples. As will be seen, the findings point to distinct offending trajectories, with some groups offending at low rates, others increasing in delinquency over time, and yet others that began offending at high levels and dropped considerably across the three time periods.

Figure 1. Bronx Sample Trajectory Analysis.

Note: BYS= Borica Youth Study. Group 1: no offending across the three waves; group 2: nonzero offending rate at wave 1, no offending at waves 2 and 3; group 3: nonzero but slight increase across the three time periods; group 4: desisting trajectory; group 5: high rate of offending and increase over time.

Figure 2. San Juan Sample Trajectory Analysis.

Note: BYS = Borica Youth Study. Group 1: no offending across the three waves; group 2: very low but nonzero across the three time periods; group 3: very low but stable rate across time; group 4: rapid decline trajectory.

Bronx sample

The Bronx trajectories are shown in Figure 1. A five-group solution provided the best fit. Group 1, representing 49.1 percent of the sample, included the nonoffending individuals who abstained from delinquency across the three time periods. The second group (37.4 percent) had a nonzero offending rate at the first wave but then dropped to virtually no offending at waves 2 and 3.7 Group 3 (8.1 percent) represented an initially low offending group of youth who increased their offending, albeit slightly, in waves 2 and 3 but remained at a rate of fewer than four different offenses per year. Group 4 (4.2 percent) began at an initially high rate of offending (almost six different offenses per year) but then approached almost no offenses at waves 2 and 3. In contrast, group 5 (1.3 percent) exhibited an increasing amount of involvement in different types of delinquency over time, from about six different acts at wave 1 to almost eight different acts at wave 3.8 In addition to the presence of an increasing-delinquency group, it is interesting that in the Bronx sample, groups 4 and 5 began at the same level of offending, but group 4 sharply dropped its involvement, whereas group 5 increased its involvement.

San Juan sample

Figure 2 displays the predicted offending trajectories for the San Juan sample and points to some very important distinctions, notably that a four-group solution emerged for San Juan participants (compared with the five-group solution for the Bronx participants). Group 1 (59.3 percent) represented a nonoffending group, exhibiting fewer than one offense at each of the three time periods. Group 2 (34.9 percent) was somewhat similar to the first group, except that it had a slightly higher average offending score at each wave (particularly the first wave), although its general levels were of very low offending. Group 3 (4.2 percent) exhibited a fairly low but stable offending rate across the three time periods, with a frequency of offending noticeably higher than that of group 2. Finally, group 4 (1.6 percent), an initially high delinquency group, was composed of individuals who exhibited a very high offending rate at wave 1 but then dropped sharply at wave 2 and exhibited almost no offending at wave 3. Unlike the Bronx results, there was no increasing-delinquency trajectory among San Juan participants. This is a particularly important finding (and feature) of the trajectory analysis, because it would have been obscured in any aggregate analysis of the age-crime relationship and/or a similar analysis combining the two sites.

How Do the Groups Vary According to Risk Factors?

A major aim of the BYS was to measure as many factors as possible that could be related to conduct disorder, delinquency, and other diagnostic criteria. Clearly, including the entire range of risk and protective factors is beyond the scope of any single study. We followed extant research on risk and protective factors (Chung et al. 2002; Loeber and Farrington 1998) in distinguishing the offender trajectories, but we also moved beyond this line of research and were sensitive to the specific experiences to which Hispanics may be exposed, especially with respect to acculturation (Berry 1998; Fridrich and Flannery 1995; Smart and Smart 1995; Vega, Gil, and Kolody 2002).

We present several comparisons of the groups across the risk factors (as reported by children and adolescents). We began with a site-specific analysis of variance (ANOVA) in which we compared the means of the risk factors identified above across the different trajectories. Second, we estimated a series of multinomial logistic regression models, attempting to discriminate between group membership using the entire range of risk and protective factors. We also provide the average delinquency scores, across all three waves, but we do not provide any specific interpretation, because these scores were used in the calibration of the trajectory groups. The ANOVA results may be found in Tables 4 (Bronx) and 5 (San Juan).

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance Results and Group Mean Covariate Levels: Bronx Sample

| Variable | Gl | G2 | G3 | G4 | G5 | F 9.92* | Tukey’s b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.57 | 1.42 | 1.37 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 9.92* | Gl > G4, G5 |

| Attitudes toward delinquency | 2.24 | 3.27 | 6.25 | 7.52 | 5.73 | 27.66* | G3 > Gl, G2; G4 > Gl, G2; G5 > Gl, G2 |

| Sensation seeking | 2.99 | 3.97 | 4.60 | 5.25 | 6.86 | 27.11* | G3 > Gl; G4 > Gl, G2; G5 > Gl, G2, G3, G4 |

| Self-esteem | 12.92 | 12.58 | 11.48 | 12.00 | 12.67 | 5.40* | None |

| Peer relationships | 4.03 | 4.03 | 3.89 | 3.73 | 3.60 | 1.36 | None |

| Peer delinquency | .20 | .24 | .31 | .42 | .25 | 5.55* | G4>G1 |

| Parent-child interaction | .79 | .77 | .76 | .74 | .70 | 1.87 | None |

| Exposure to violence | 1.62 | 2.97 | 3.88 | 5.35 | 5.53 | 27.89* | G3 > Gl; G4 > Gl, G2; G5 > Gl, G2 |

| Coercive discipline | .28 | .44 | .50 | .63 | .51 | 9.82* | G4>G1 |

| Acculturation | 3.60 | 3.63 | 3.61 | 3.69 | 3.41 | .75 | None |

| School environment | 2.75 | 3.72 | 3.89 | 4.46 | 4.80 | 10.37* | G4>G1;G5>G1 |

| Social support | 1.88 | 1.86 | 1.79 | 1.76 | 1.90 | 1.25 | None |

| Locus control | .70 | .76 | .88 | .87 | .77 | 6.51* | None |

| Stressful life events | .71 | 1.10 | 1.02 | 1.47 | 1.87 | 7.53* | G5>G1,G2, G3 |

| Welfare | .91 | .90 | 1.07 | .88 | .80 | .61 | None |

| Delinquency | |||||||

| Wave 1 | .00 | .99 | 1.66 | 5.83 | 5.86 | 576.37* | G2 > Gl; G3 > Gl, G2; G4 > Gl, G2, G3; G5 > Gl, G2, G3 |

| Wave 2 | .00 | .61 | 2.82 | .82 | 8.00 | 474.94* | G2 > Gl; G4 > Gl; G3 > Gl, G2, G4; G5 > Gl, G2, G3, G4 |

| Wave 3 | .00 | .41 | 2.94 | .24 | 8.40 | 346.77* | G3 > Gl, G2, G4; G5 > Gl, G2, G3, G4 |

Note: G = group. Gl: no offending across the three waves; G2: nonzero offending rate at wave 1, no offending at waves 2 and 3; G3: nonzero but slight increase across the three time periods; G4: desisting trajectory; G5: high rate of offending and increase over time.

p < .05.

Among the Bronx youth, the results indicate that 10 of the 15 risk and protective factors showed significant differences across the five trajectories, as shown by the significant F value, and Tukey’s b comparisons are provided to indicate which groups differed significantly from one another. These variables included gender, attitudes toward delinquency, sensation seeking, self-esteem, peer delinquency, exposure to violence, coercive discipline, school environment, locus control, and stressful life events.

Recalling that group 1 was clearly a nonoffending group, that group 4 was a decreasing-delinquency group, and that group 5 was an increasing-delinquency group, several differences are worth highlighting. For example, for groups 4 and 5, which reported almost identical delinquency at wave 1, many of the variables showed very similar average scores; in fact, the two groups did not differ on any of the variables. Yet, the two high-offending (at baseline) groups showed the worst risk compared with the other groups, with group 5 (the highest rate offending group) evincing the highest sensation seeking, attitudes toward delinquency, and exposure to violence. As a general rule, the nonoffender trajectory showed the lowest scores on the risk factors (i.e., the lowest risk) but the highest scores on the protective factors. Specifically, the nonoffender group was composed of more female youth and had the lowest average value of youth attitudes toward delinquency, the lowest sensation seeking, and the lowest exposure to violence, all of which appear magnified when this group is compared with the two highest offending trajectories. The Bronx trajectories did not differ with respect to acculturation.

Turning to the San Juan youth, recall that there were only four trajectories identified and a much lower average delinquency score compared with the Bronx sample. Here, group 1 was clearly a nonoffender group, group 4 was a decreasing-delinquency group, and group 3 averaged a low but steady level of delinquency over time. The ANOVA results indicated that 12 of the 15 variables yielded significant differences across the groups: gender, attitudes toward delinquency, sensation seeking, self-esteem, peer relationships, peer delinquency, exposure to violence, coercive discipline, acculturation, school environment, locus control, and stressful life events. The nonoffender trajectory (group 1) exhibited more female youth, lower exposure to violence, lower peer delinquency, and higher self-esteem, especially compared with the higher delinquency trajectories. Group 4, which reported the highest average delinquency score at wave 1, tended to have the highest score on most risk factors and the lowest score on most protective factors. On average, this group reported very high attitudes in favor of delinquency, the lowest self-esteem, the highest stressful life events, and the highest acculturation.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results

Because the previous analyses considered each of the risk and protective factors in isolation, not in unison, we next present a series of multinomial logistic regression models in which we compared the ability of the risk and protective factors to simultaneously differentiate among the offender groups in the two sites (Table 6). Across all three estimations, the nonof-fender trajectory served as the reference group with which we compared each of the offender trajectories. Multicollinearity was not a problem in these regression analyses, because nearly all of the bivariate correlations among the independent variables were small (.01 to .29), and none was larger than .36 for the Bronx analysis or .47 for the San Juan analysis.

Table 6.

Multinomial Regression Results

| Bronx Samplea |

San Juan Sampleb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | SE | exp(B) | b | SE | exp(B) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | −.49* | .15 | .62 | −.26* | .13 | .77 |

| Group 3 | .70* | .27 | .50 | −.14 | .31 | .87 |

| Group 4 | −1.08* | .39 | .34 | −.20 | .72 | .82 |

| Group 5 | −.96 | .67 | .38 | |||

| Attitudes toward delinquency | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .03 | .02 | 1.03 | .01 | .01 | 1.00 |

| Group 3 | .11* | .02 | 1.11 | .01 | .02 | 1.01 |

| Group 4 | .11* | .03 | 1.12 | .07* | .03 | 1.07 |

| Group 5 | .06 | .05 | 1.06 | |||

| Sensation seeking | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .11* | .03 | 1.12 | .10* | .03 | 1.11 |

| Group 3 | .20* | .05 | 1.22 | .38* | .06 | 1.46 |

| Group 4 | .25* | .07 | 1.28 | .29* | .15 | 1.34 |

| Group 5 | .59* | .14 | 1.81 | |||

| Self-esteem | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | −.05 | .03 | .95 | −.05 | .02 | .96 |

| Group 3 | −.17* | .04 | .85 | −.03 | .06 | .97 |

| Group 4 | −.08 | .06 | .92 | −.18 | .12 | .83 |

| Group 5 | −.08 | .10 | .92 | |||

| Peer relationships | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .07 | .07 | 1.08 | −.05 | .07 | .96 |

| Group 3 | .07 | .12 | 1.07 | .16 | .17 | 1.17 |

| Group 4 | .03 | .15 | 1.03 | .10 | .36 | 1.10 |

| Group 5 | −.27 | .24 | .77 | |||

| Peer delinquency | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .05 | .22 | 1.05 | .31 | .21 | 1.37 |

| Group 3 | .27 | .34 | 1.30 | .64 | .42 | 1.90 |

| Group 4 | .82* | .40 | 2.27 | −.52 | .89 | .59 |

| Group 5 | −.66 | .94 | .52 | |||

| Parent-child interaction | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | −.26 | .40 | .77 | .01 | .31 | 1.01 |

| Group 3 | .34 | .71 | 1.41 | .03 | .71 | 1.03 |

| Group 4 | −.19 | .92 | .83 | −1.71 | 1.40 | .18 |

| Group 5 | −1.34 | 1.41 | .26 | |||

| Exposure to violence | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .09* | .03 | 1.09 | .12* | .02 | 1.13 |

| Group 3 | .15* | .04 | 1.16 | .16* | .04 | 1.18 |

| Group 4 | .19* | .04 | 1.21 | .38* | .06 | 1.46 |

| Group 5 | .19* | .07 | 1.21 | |||

| Coercive discipline | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .35* | .14 | 1.41 | .45* | .12 | 1.57 |

| Group 3 | .18 | .24 | 1.19 | .78* | .23 | 2.18 |

| Group 4 | .36 | .29 | 1.44 | 1.48* | .47 | 4.41 |

| Group 5 | .15 | .53 | 1.16 | |||

| Acculturation | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .22 | .12 | 1.24 | .15 | .10 | 1.16 |

| Group 3 | .29 | .21 | 1.34 | .20 | .23 | 1.22 |

| Group 4 | .81* | .31 | 2.26 | .30 | .41 | 1.35 |

| Group 5 | .35 | .55 | 1.41 | |||

| School environment | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .08* | .03 | 1.08 | .06* | .03 | 1.06 |

| Group 3 | .04 | .04 | 1.04 | .10* | .05 | 1.11 |

| Group 4 | .11* | .05 | 1.11 | .09 | .09 | 1.09 |

| Group 5 | .15 | .09 | 1.16 | |||

| Social support | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | −.11 | .16 | .90 | −.20 | .14 | .82 |

| Group 3 | −.43 | .28 | .65 | −.77* | .34 | .47 |

| Group 4 | −.78* | .38 | .46 | −.15 | .82 | .86 |

| Group 5 | ‒.05 | .72 | .95 | |||

| Locus control | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .02 | .19 | 1.02 | .22 | .19 | 1.25 |

| Group 3 | .63 | .34 | 1.87 | .05 | .44 | 1.05 |

| Group 4 | .23 | .46 | 1.25 | −.30 | .95 | .74 |

| Group 5 | −.26 | .77 | .77 | |||

| Stressful life events | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | .12* | .05 | 1.13 | .05 | .05 | 1.05 |

| Group 3 | .01 | .09 | 1.01 | .06 | .10 | 1.06 |

| Group 4 | .13 | .11 | 1.14 | .05 | .16 | 1.05 |

| Group 5 | .25 | .15 | 1.29 | |||

| Welfare | ||||||

| Group 1 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Group 2 | −.02 | .07 | .99 | −.17* | .07 | .84 |

| Group 3 | .15 | .13 | 1.16 | −.20 | .16 | .82 |

| Group 4 | −.06 | .17 | .95 | −.32 | .37 | .73 |

| Group 5 | .04 | .30 | 1.04 | |||

Note: Group 1 (nonoffenders) served as the reference category for the Bronx and San Juan analyses.

Group 1: no offending across the three waves; group 2: nonzero offending rate at wave 1, no offending at waves 2 and 3; group 3: nonzero but slight increase across the three time periods; group 4: desisting trajectory; group 5: high rate of offending and increase over time.

Group 1: no offending across the three waves; group 2: very low but nonzero across the three time periods; group 3: very low but stable rate across time; group 4: rapid decline trajectory.

p < .05.

The multinomial logistic regression results are presented separately for the Bronx and San Juan samples (for which group 1 was the nonoffender reference group). There were some similarities and some differences across the two sites when considering the risk and protective factors together. Among the Bronx youth, sensation seeking and exposure to violence emerged as significant discriminators between the highest (group 5) and the nonoffender (group 1) trajectories. Another unique finding in the Bronx concerned acculturation; here, the results indicated that group 4, the decreasing-delinquency trajectory, reported a higher acculturation score and a lower amount of social support compared with the nonoffender trajectory. Among San Juan respondents, results substantively similar to those reported above emerge. For example, compared with the nonoffender trajectory, all of the offender trajectories reported higher sensation seeking and more exposure to violence. There were some interesting differences across the two sites. For example, in San Juan, acculturation did not distinguish the four trajectories, but coercive discipline did. All offending trajectories in San Juan reported more coercive discipline compared with the nonoffender trajectory. Furthermore, self-esteem, peer relationships, and peer delinquency did not emerge as significant discriminators across the trajectories.

Discussion

Using data from two samples of Hispanic youth in the Bronx and in San Juan, we used a mixture methodology to identify unique trajectories of youth following particular paths of delinquency and then to examine how several risk and protective factors were able to distinguish across the trajectories. The current research represents the first application of this methodology to a sample of Hispanic youth in an effort to study their delinquency progression as they transition into adolescence.

Several key findings emerged. First, five unique delinquency trajectories were identified among Bronx participants but only four among San Juan participants. Second, there were important site differences with respect to the number of trajectories and the overall average level of delinquency among the trajectories. Although the smallest group in the San Juan trajectory analysis (group 4) demonstrated the highest rate of delinquency across both sites (but declined considerably across waves), in general, the Bronx youth and the majority of the Bronx trajectory groups displayed more elevated levels of delinquency compared with the San Juan youth and the San Juan trajectory groups. Third, an analysis of how the risk and protective factors varied across the trajectories yielded results similar to those observed in some American-based samples, but in analyses that compared some Hispanic-specific variables (i.e., acculturation), unique patterns emerged. Fourth, when the risk and protective factors were considered together, the findings indicated that some factors emerged as more salient than others. For example, in the Bronx, sensation seeking and exposure to violence strongly discriminated offender from nonoffender trajectories (with the highest offending group reporting the highest risk). In San Juan, the results were substantively the same. So, even though the youth live in different cultural, social, and ecological contexts, the results were, for the most part, more similar than different.

These results have several implications. First, although the number of trajectories was slightly different across cultural contexts (five in the Bronx and four in San Juan), the influence of risk factors was more similar than different across sites. For instance, sensation seeking and exposure to violence were significant risk factors for high-risk delinquency trajectories across contexts. Thus, there is some evidence that prevention programs can target similar risk factors across urban Puerto Rican youth. Second, the offending trajectories improve knowledge on similarities and differences in the influence of factors during childhood and adolescence that are associated with delinquency progression. This knowledge is relevant to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers interested in the development of prevention efforts targeting the reduction of delinquency during this time period. Still, caution and care should be exerted to prevent “doing something” to those youth predicted to be high-rate offenders, because prediction remains far from perfect, and what is done with that information (e.g., treating, stigmatizing, incarcerating) is sometimes not undertaken in the best interest of the youth. Yet prediction generally, and the use of prediction tools in particular, is likely to be a better option than guessing.

Several limitations preclude a more definitive statement about the nature and course of Hispanic delinquency. For example, our data were composed solely of static risk and protective factors, so we were unable to examine changes over time in risk and protective factors. One interesting case concerned groups 4 and 5 in the Bronx, whose delinquency started at the same initial point but diverged dramatically thereafter. What factors could account for these changes? Although most of the trajectory literature has used static risk and protective factors to understand differences between trajectories, some research has shown that some changes in life events (i.e., relationships and employment) relate to some changes in delinquency (Horney et al. 1995; Piquero et al. 2002). The collection of such data among Hispanic youth is needed before any further speculation can be made about how time-varying effects may alter the progression of delinquency across different cultures and contexts.

Second, we did not consider information on neighborhood and social contextual characteristics. How the youth in the Bronx and San Juan navigate these social circumstances and how these social factors relate to delinquency remain undetected.

Third, although this was the first application of the group-based methodology to examine trajectories of Hispanic delinquency, our analysis included only a small number of observation points (though others have used similarly small numbers; Nagin and Tremblay 2005). Thus, further studies using long-term follow-up of Hispanics will extend this preliminary work. On a related note, trajectory estimation is sometimes useful and other times not useful. Our motivation here was to examine whether distinct trajectories emerged from the data, whether they were similar or different across the two samples, and then how a set of risk and protective factors were related to the site-specific trajectories. Such descriptive information is the cornerstone of criminology and is especially pertinent in the current study given the paucity of such research among Hispanics. Still, other methodological and statistical approaches should also be applied to the BYS data in an effort to arrive at a triangulation of the longitudinal patterning and nature of crime among Puerto Rican youth.

Fourth, we relied on self-reported delinquency to estimate the group-based trajectories. It is important that future research use official measures of Hispanic offending to investigate if similar trajectories emerge using alternative offending measures.

Finally, the issue of temporal order is always of concern in a longitudinal study that begins to follow subjects after birth. In the BYS, the risk and protective factors were measured at the same time as delinquency in the first assessment of the trajectory analysis. Of course, this temporal order issue affects the interpretation of study results (i.e., high peer delinquency or low self-esteem may result from delinquency rather than be a predictor of delinquency) and should be considered with respect to study findings.

In short, aside from the lack of many substantive differences across sites, the finding indicating that the risk factors were more similar than different suggests more generality in the causal processes associated with delinquency, with the important exception that acculturation was related to offending in one of the Bronx trajectory groups. And although most trajectories were declining in delinquency over time, there still remained an offender trajectory in the Bronx that showed stable and rather high delinquency over time. These findings point to some important similarities and differences with respect to the patterning and nature of delinquency among Hispanic youth across two distinct cultural contexts.

Table 5.

Analysis of Variance Results and Group Mean Covariate Levels: San Juan Sample

| Variable | Gl | G2 | G3 | G4 | F * | Tukey’s b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1.54 | 1.42 | 1.37 | 1.33 | 7.17 | None |

| Attitudes toward delinquency | 2.63 | 3.44 | 5.66 | 18.19 | 46.32* | G3>G1;G4>G1, G2, G3 |

| Sensation seeking | 2.53 | 3.21 | 4.89 | 4.71 | 29.60* | G3>G2, G1;G4>G1, G2 |

| Self-esteem | 12.45 | 11.83 | 12.04 | 10.76 | 6.76* | Gl >G4 |

| Peer relationships | 4.42 | 4.23 | 4.39 | 4.00 | 4.17* | None |

| Peer delinquency | .19 | .27 | .34 | .46 | 12.53* | G3>G1;G4>G1, G2 |

| Parent-child interaction | .73 | .71 | .70 | .66 | 1.46 | None |

| Exposure to violence | 1.48 | 2.90 | 4.16 | 15.43 | 141.73* | G2 > Gl; G3 > Gl; G4 > Gl, G2, G3 |

| Coercive discipline | .24 | .46 | .66 | 1.50 | 54.27* | G3>G1;G4>G1, G2, G3 |

| Acculturation | 1.85 | 1.98 | 2.09 | 2.47 | 11.09* | G4>G1,G2, G3 |

| School environment | 2.09 | 2.83 | 3.68 | 5.05 | 18.53* | G3>G1;G4>G3, G2, Gl |

| Social support | 2.05 | 2.01 | 1.99 | 2.15 | 1.16 | None |

| Locus control | .71 | .77 | .79 | 1.10 | 10.23* | G4>G1,G2, G3 |

| Stressful life events | .84 | 1.17 | 1.39 | 4.35 | 41.98* | G4>G1,G2, G3 |

| Welfare | .77 | .66 | .64 | 1.05 | 2.21 | None |

| Delinquency | ||||||

| Wave 1 | .00 | 1.01 | 2.98 | 11.81 | 1,275.18* | All group differences significant |

| Wave 2 | .00 | .57 | 2.52 | 1.58 | 248.02* | All group differences significant |

| Wave 3 | .00 | .49 | 2.66 | .16 | 357.08* | G2>G1,G4;G3>G1,G2, G4 |

Note: G = group. Gl: no offending across the three waves; G2: very low but nonzero across the three time periods; G3: very low but stable rate across time; G4: rapid decline trajectory.

p< .05.

Appendix.

Covariates

| Variable | Description | Cronbach’s α |

Source | Example Question | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitudes toward delinquency |

39-item scale; higher scores reflect permissive attitudes toward antisocial behavior |

.93 | Loeber et al. (1998) | Do you think it’s ok for someone your age to: Purposely damage or destroy property that does not belong to them? |

Always wrong sometimes right almost always right |

| Sensation seeking |

10-item scale; higher scores reflect higher thrill and adventure seeking and social disinhibition |

.72 | Russo et al. (1991, 1993) | Sometimes you like to do things that are a little scary. |

No, yes |

| Self-esteem | 8-item scale; higher scores reflect higher scholastic and athletic competence, social acceptance, behavioral conduct, and physical appearance |

.46 | Harter (1982) | Now I am going to ask you how you feel about yourself. Tell me if you feel this way or not . You find yourself pretty/handsome and like the way you look. |

No, yes |

| Peer relationships |

5-item scale; higher scores indicate higher sensation seeking, including belonging, feeling liked, and getting along with others |

.58 | Hudson (1992) | You get along well with kids about your age. |

Rarely or never, often or all the time |

| Peer delinquency |

Higher scores reflect more antisocial behaviors among peers |

.85 | Loeber et al. (1998) | During the past year, how many of your friends have: Purposely damaged or destroyed other people’s things? |

Only a few or none o f them, about half of them, most of them |

| Parent-child interaction |

12-item scale; higher scores reflect positive parent-child interactions |

.75 | Loeber et al. (1998) | How often do your parents/caretakers do things with you? |

Never or rarely, often |

| Exposure to violence |

Exposure to community violence (happened to self, saw it happen to someone heard of it happening); scale score weighing different levels of exposure; higher scores reflect higher exposure to community violence |

N/A |

Raia (1995) ; Richters and Martinez (1993) |

Someone has broken into or tried to force their way into the house or apartment? |

No, yes |

| Coercive discipline |

6-item scale; higher scores reflect child’s perception of quality of parental discipline |

.67 | Goodman et al. (1998) | Did parents/caregivers punish you by taking away some privilege, like not letting you watch TV or go to the movies or go outside to do the things you want to do? |

Never or only once in a while, often |

| Acculturation (of youth) |

9-item scale: Cultural Life Style Inventory (bidirectional l scale); higher scores reflect higher preference for English and other ethnic characteristics |

.86 |

Magafia et al. (1996) ; Mendoza (1989) |

In what language are the stories, comic books, or books that you read or are read to you? Are they… |

Only Spanish; mostly Spanish; both English and Spanish, about equal; mostly English; only English |

| School environment |

8-item scale; higher scores reflect negative characteristics of the school environment |

.55 | In the past year, many substitute teachers giving classes in your school? |

No, yes | |

| Social support | Higher scores indicate higher youth support |

.49 | Thoits (1995) | When you have a problem, how often do you talk about it with your family? |

Never, only sometimes often, always |

| Locus control | 12-item scale; higher values reflect external locus of control |

.42 | Nowicki and Strickland (1973) | Some kids are just born lucky. | No, yes |

| Stressful life events |

Higher scores indicate higher levels of stress |

N/A | Goodman et al. (1998); Johnson and McKutcheon (1980) | During the last 12 months, did you move to a new home (permanently, not a temporary residence that is not your home)? |

No, yes |

| Welfare | Higher scores indicate that some of the household income was from welfare or public assistance |

Was any of the household income from welfare or public assistance? I do not mean Social Security. |

No, yes |

Note: N/A = not available.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health through grants RO-1 MH56401 (Hector Bird, principal investigator) and P20 MD000537-01 (Glorisa Canino, principal investigator) from the National Center for Minority Health Disparities, and the Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida. We acknowledge the important contributions of Vivian Febo, PhD, Iris Irizarry, MA, Linan Ma, MSPH, and of all of the dedicated staff members who participated in this complex study.

Biographies

Mildred M. Maldonado-Molina is an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Health Policy Research and the Institute for Child Health Policy, College of Medicine, University of Florida. She received her doctorate in human development and family studies from The Pennsylvania State University in 2005.

Alex R. Piquero is a professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Maryland College Park. He received his doctorate in criminology from the University of Maryland College Park in 1996.

Wesley G. Jennings is an assistant professor in the Department of Justice Administration at the University of Louisville. He received his doctorate in criminology from the University of Florida in 2007.

Hector Bird is a professor emeritus of clinical psychiatry in the Division of Child Psychiatry at Columbia University. He earned his medical degree from Yale Medical School in 1965.

Glorisa Canino is a professor and director of the Behavioral Sciences Research Institute at the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus. She received her doctorate in psychology from Temple University in 1974.

Footnotes

Of course, whereas a sample in metropolitan San Juan can be considered to represent San Juan urban children on the island, the sample in the South Bronx was not representative of Puerto Rican children throughout the United States. Thus, the findings do not necessarily generalize to all children of Puerto Rican background in the country. Furthermore, although the sample in the South Bronx was likely typical of aggregations of Puerto Rican migrants in other urban centers in the United States, the possibility exists that differences emerging from comparisons of the two samples might be due to a wide range of differences in family characteristics that may lead some individuals to migrate and others to stay behind. Some further notes on the context from which both samples were drawn are in order. According to Bird, Canino, et al. (2006), there were no significant differences in age and gender distributions between Puerto Rican children in San Juan metropolitan areas and the South Bronx. However, the levels of maternal education and the household constellations of the families were different. The mothers in Puerto Rico were more highly educated, and a much higher proportion of households in the Bronx were single-parent households (45.4 percent vs. 27.8 percent in Puerto Rico), mimicking general population characteristics in the United States and Puerto Rico. Furthermore, although there were differences in income between the sites (e.g., the percentage of households receiving welfare or public assistance), poverty may not have the same effect in both contexts, because roughly half of the population in Puerto Rico is poor (48 percent, according to the 2000 U.S. census), compared with a much smaller percentage of the population in the United States who are considered at or below the poverty level. These differences notwithstanding, the lack of data on Hispanic offending in the criminological literature suggests that the current study represents an important first step.

We should note that although it may be somewhat surprising at first glance to learn that there was a decline in offending over time in the BYS, extant self-reported delinquency research indicates that aggregate self-reported offending peaks in early to middle adolescence, while official records of offending indicate a peak in late adolescence (Blumstein et al. 1986; Moffitt et al. 2001; Piquero et al. 2003). Thus, given the age range, the results are not that far removed from the extant literature. With specific relation to the BYS, the declining delinquency trend could be due to (1) a mixture of age ranges (the older youth who had high levels dropped off quickly, in part driving the trend downward), (2) the types of acts used in the scale seeing less involvement, and (3) the levels of self-reported delinquency being already high at the first stage of data collection (primarily at the end of the first decade and beginning of the second decade of life). The decline in offending observed over time seen in the San Juan sample was not completely observed in the Bronx sample, in which there was a trajectory (group 5) whose offending was both moderate and stable over the three waves. Thus, the decline in delinquency was not entirely evidenced across both samples, and the trajectory methodology nicely illustrated the differences within the offender sample (especially in the Bronx).

According to D’Unger et al. (1998), “this statistical criterion favors model parsimony by extracting a penalty for complicating a model (by adding parameters) that increases with the log of the sample size” (p. 1627). Furthermore, this BIC for model selection embodies the intuitive notion that when an analyst complicates a model by adding parameters, the pay-off in terms of a decrease in the log maximized likelihood function of the model should be larger than this penalty (Schwartz 1978).

It is true that various trajectory estimations can provide similarly reasonable fits to the data. It was through the use of descriptive plots, the fit between actual and predicted values, and more formal criteria that we arrived at our decision regarding the final set of trajectory estimations presented here.

because the groups are intended as an approximation of a more complex underlying reality, the objective is not to identify the “true” number of groups. Instead, the aim is to identify as simple a model as possible that displays the distinctive features of the population distribution of trajectories. (Nagin and Tremblay 2005: 882)

It is useful to think of the trajectories as clusters of similar individual trajectories, as in cluster analysis, but in trajectory space.

All average posterior probabilities were above the standard cutoff of .70 (Nagin and Land 1993). Of course, as in most trajectory-based efforts, there is always the possibility of the misclassification of individuals to particular trajectories.

It is likely that this was not an age effect, because individuals in this group were quite young at wave 1 (9.45 years old) and only got older over time (average age at wave 3 = 11.22 years), thereby increasing the likelihood that they would be engaging in more crime as they approached the teenage years.

Group 5 also included the oldest participants in the data, with average ages of 11.46 years at wave 1, 12.57 years at wave 2, and 13.46 years at wave 3.

Contributor Information

Mildred M. Maldonado-Molina, University of Florida

Alex R. Piquero, University of Maryland College Park

Wesley G. Jennings, University of Louisville

Hector Bird, Columbia University.

Glorisa Canino, University of Puerto Rico.

References

- Agnew Robert. Building on the Foundation of General Strain Theory: Specifying the Types of Strain Most Likely to Lead to Crime and Delinquency. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:319–361. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew Robert. Pressured into Crime: An Overview of General Strain Theory. Los Angeles: Roxbury; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arkes Jeremy. Does the Economy Affect Teenage Substance Use? Health Economic. 2007;16:19–36. doi: 10.1002/hec.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry John. W. Acculturation as Varieties of Adaptation. In: Padilla Amado M., editor. Acculturation, Theory, Models, and Some New Findings. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1980. pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Berry John W. Acculturative Stress. In: Organista PB, Chun KM, Marin G, editors. Readings in Ethnic Psychology. New York: Routledge; 1998. pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bird Hector R, Canino Glorisa J, Davies Mark, Duarte Cristiane S, Febo Vivian, Ramirez Rafael, Hoven Christina, Wicks Judith, Musa George, Loeber Rolf. A Stud of Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Puerto Rican Youth: I. Background, Design, and Survey Methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1032–1040. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227878.58027.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird Hector R, Davies Mark, Duarte Cristiane, Shen Sa, Loeber Rolf, Canino Glorisa J. A Study of Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Puerto Rican Youth: II. Baseline Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Correlates in Two Sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45:1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227879.65651.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird Hector R, Shrout Patrick E, Davies Mark, Canino Glorisa, Duarte Cristiane S, Shen Sa, Loeber Rolf. Longitudinal Development of Antisocial Behaviors in Young and Early Adolescent Puerto Rican Children at Two Sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:5–14. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242243.23044.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein Alfred, Cohen Jacqueline, Roth Jeffrey, Visher Christy., editors. Criminal Careers and “Career Criminals,” Vol 1. Report of the Panel on Criminal Careers, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges George, Steen Sara. Racial Disparities in Official Assessments of Juvenile Offenders: Attributional Stereotypes as Mediating Mechanisms. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:554–570. [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Whiteman Martin. Drug Use and Delinquency: Shared and Unshared Risk Factors in African American and Puerto Rican Adolescents. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1997;158:25–39. doi: 10.1080/00221329709596650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook Judith S, Whiteman Martin, Balka Elinor B, Win Pe T, Gursen Michael D. Similar and Different Precursors to Drug Use and Delinquency among African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1998;159:13–29. doi: 10.1080/00221329809596131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino Glorisa, Shrout Patrick E, Rubio-Stipec Maritza, Bird Hector R, Bravo Milagros, Ramirez Rafael, Chavez Ligia, Alegria Margarita, Bauermeister José J, Hohmann Ann, Ribera Julio, Garcia Pedro, Martinez-Taboas Alfonso. The DSM-IV Rates of Child and Adolescent Disorders in Puerto Rico. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:85–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes Richard C, Castro Felix G. Stress, Coping, and Mexican American Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1985;1:1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chung Ick-Joong, Hill Karl G, Hawkins JDavid, Gilchrist Lewayne D, Nagin Daniel S. Childhood Predictors of Offense Trajectories. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2002;39:60–92. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton Claudia J, Korbin Jill E, Su Marilyn, Chow Julian. Community Level Factors and Child Maltreatment Rates. Child Development. 1995;66:1262–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum Rosa M, Lillie-Blanton Marsha, Anthony James C. Neighborhood Environment and Opportunity to Use Cocaine and Other Drugs in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;43:155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Susan C, Duncan Terry E, Strycker Lisa A. A Multilevel Analysis of Neighborhood Context and Youth Alcohol and Drug Problems. Prevention Science. 2002;3:125–133. doi: 10.1023/a:1015483317310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Unger Amy V, Land Kenneth C, McCall Patricia L. Sex Differences in Age Patterns of Delinquent/Criminal Careers: Results from Poisson Latent Class Analyses of the Philadelphia Cohort Study. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18:349–375. [Google Scholar]

- D’Unger Amy V, Land Kenneth C, McCall Patricia L, Nagin Daniel S. How Many Latent Classes of Delinquent/Criminal Careers? Results from Mixed Poisson Regression Analyses. American Journal of Sociology. 1998;103:1593–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Delbert S, Huizinga David, Ageton Suzzane. Explaining Delinquency and Drug Use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Delbert S, Wilson William J, Huizinga David, Sampson Robert J, Elliott Amanda, Rankin Bruce. The Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Adolescent Development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33:389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington David P, Loeber Rolf, Stouthamer-Loeber Magda. How Can the Relationship between Race and Violence be Explained? In: Hawkins Darnell F., editor. Violent Crimes: Assessing Race and Ethnic Differences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Fridrich Angela, Flannery Daniel J. The Effects of Ethnicity and Acculturation on Early Adolescent Delinquency. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1995;4:69–87. [Google Scholar]