Abstract

Objective:

To review the management of fecal incontinence, which affects more than 1 in 10 people and can have a substantial negative impact on quality of life.

Methods:

The medical literature between 1980 and April 2012 was reviewed for the evaluation and management of fecal incontinence.

Results:

A comprehensive history and physical examination are required to help understand the severity and type of symptoms and the cause of incontinence. Treatment options range from medical therapy and minimally invasive interventions to more invasive procedures with varying degrees of morbidity. The treatment approach must be tailored to each patient. Many patients can have substantial improvement in symptoms with dietary management and biofeedback therapy. For younger patients with large sphincter defects, sphincter repair can be helpful. For patients in whom biofeedback has failed, other options include injectable medications, radiofrequency ablation, or sacral nerve stimulation. Patients with postdefecation fecal incontinence and a rectocele can benefit from rectocele repair. An artificial bowel sphincter is reserved for patients with more severe fecal incontinence.

Conclusion:

The treatment algorithm for fecal incontinence will continue to evolve as additional data become available on newer technologies.

Introduction

Fecal incontinence is a physically and psychologically debilitating condition that has a negative impact on quality of life, leads to embarrassment and social isolation, and strains personal and family relationships. A prevalence up to 12% has been previously reported.1,2 Men and women of all ages can be affected by fecal incontinence, although studies suggest it is more prevalent with increasing age.3 In a large community-based study, the prevalence of fecal incontinence was 0.9% in adults between the ages of 40 and 64 years and 2.3% in adults older than 65 years.4 In clinical practice, more female than male patients are typically evaluated for this condition.

Pathophysiology

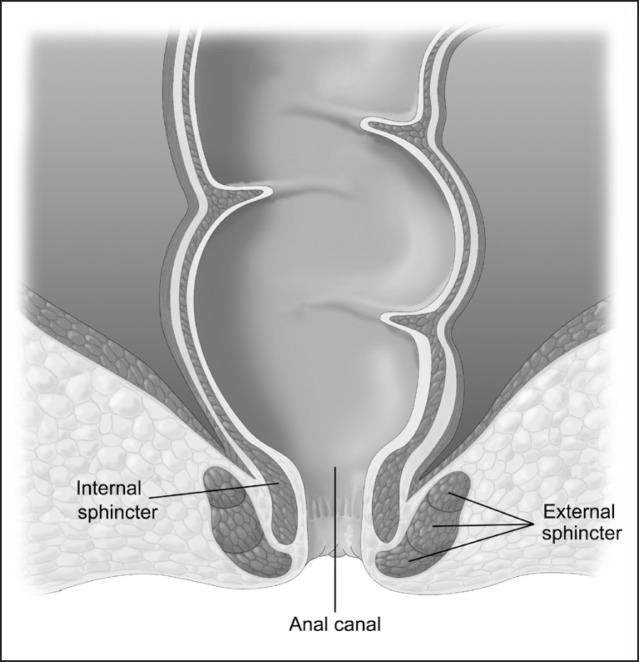

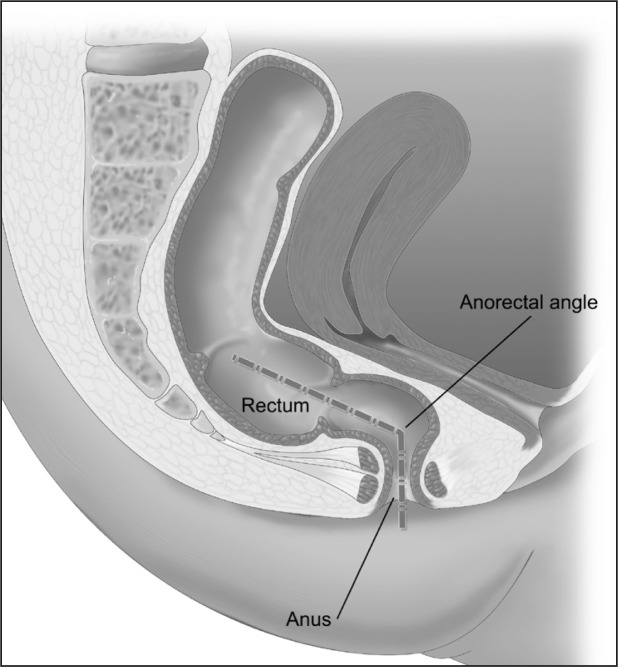

An understanding of the mechanisms involved in normal defecation can be helpful in understanding what alterations lead to fecal incontinence. The anal sphincter complex involves two muscles, the internal sphincter and the external sphincter (Figure 1). The internal sphincter muscle is a continuation of the circular muscles of the rectal wall, consists of smooth muscles, and is under autonomic nervous system control. The external sphincter muscle is a continuation of the pelvic floor musculature, consists of skeletal muscles, and is under voluntary nervous system control. In addition to the anal sphincter muscles, the acute angle of the anorectal junction provides some degree of continence control (Figure 2). During normal defecation, stool enters the rectum and causes a reflexive relaxation of the internal anal sphincter to allow sampling of the rectal content. Next, stool enters the anal canal and causes a reflexive contraction of the external sphincter in addition to some degree of voluntary contraction of the external sphincter. If the stool is not passed, it can be stored in the rectum until enough stretching of the rectum triggers a sensation of urgency and the person can find a socially appropriate setting to defecate. At the time of defecation, typically in the sitting or squatting position, a series of events happens: the angle at the anorectal junction straightens, the intra-abdominal pressure increases, the external sphincter relaxes, the rectosigmoid contracts to propel the stool, and the stool passes. After passing the stool, the external sphincter closes.

Figure 1.

Internal and external anal sphincter muscles.

Figure 2.

Anorectal angle.

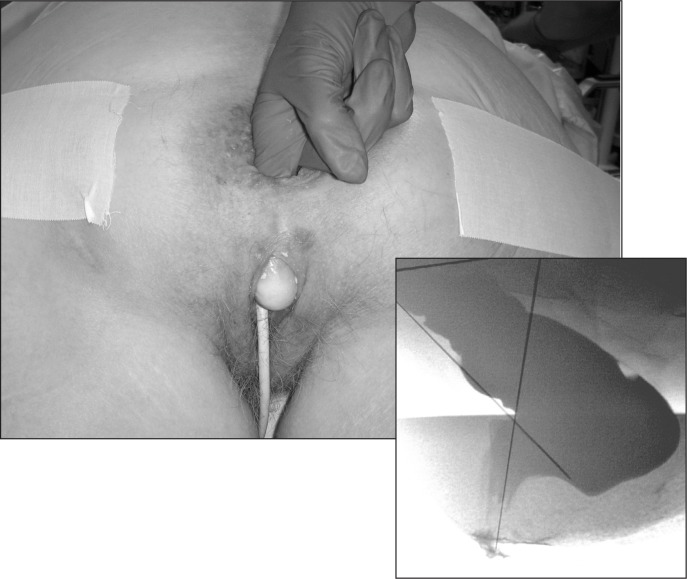

Numerous conditions can lead to fecal incontinence (see Sidebar: Causes of fecal incontinence). The etiology can vary among men and women of different ages. Trauma to the anal canal can result from disruption of the anal sphincters during childbirth, direct or indirect sphincter muscle injury during anal surgery, or other anorectal trauma. The most common cause of fecal incontinence is obstetric injury (Figure 3).5 Changes in rectal sensation or rectal compliance can result in urgency, diminished capacity of the rectum, and loss of stool control. Conditions causing inflammation of the anorectum such as inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) can result in urgency and incontinence. Denervation of the pudendal nerves from stretch injury or other neuropathic conditions are associated with fecal incontinence. Rectocele (an outpouching of the rectum into the vagina due to weak pelvic tissue) can lead to postdefecation incontinence (Figure 4). Medical conditions such as diabetes, diarrhea, obesity, neurologic diseases, and urinary incontinence may result in or contribute to the symptoms of fecal incontinence.1,2,6 In some patients, the etiology of fecal incontinence can be multifactorial. It is critical to establish the cause of incontinence because it is an important determinant of the treatment approach. Furthermore, it is important to distinguish true incontinence from pseudoincontinence. Pseudoincontinence is related to conditions such as poor anal hygiene, prolapsing internal hemorrhoids, anal fistula, fecal impaction, laxative abuse, infectious diarrheal conditions, perianal dermatologic diseases, or anorectal neoplasms.

Causes of fecal incontinence.

| Childbirth |

| Anal trauma or surgery |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Irritable bowel syndrome |

| Diarrhea |

| Radiation |

| Diabetes |

| Connective tissue disorders |

| Neurologic disorders |

| Incomplete emptying disorders (rectocele) |

| Aging |

| Dementia |

| Obesity |

| Neoplasm |

| Rectal prolapse |

| Imperforate anus |

Figure 3.

Cloacal defect with absence of perineum in a patient with severe obstetric tear.

Figure 4.

A (above) Patient with large anterior rectocele. B (right) Defecography demonstrating an anterior rectocele.

Evaluation

Comprehensive evaluation of fecal incontinence includes a detailed history, with description of bowel habits including consistency of stools and frequency of bowel movements, type of incontinence (gas, liquid stool, solid stool, urge, passive, or postdefecation), associated urgency symptoms, awareness of incontinence vs complete lack of sensation, concomitant urinary incontinence symptoms, and diet and medications. Colorectal cancer must be ruled out in those individuals with newly changed bowel habits and particularly with bleeding. The presence of urinary incontinence symptoms is important to elicit because it suggests weakness of the global pelvic floor muscles. Female patients are asked about prior childbirth history (ie, vaginal deliveries, tears, or episiotomies). All patients are asked about prior anal surgery, trauma to anus or sexual instrumentation, prior radiation therapy, and systemic conditions such as diabetes and neurologic disease.

Differentiating the loss of solid vs liquid stool is helpful. In general, it is more difficult for the anorectum to sense and to hold liquid stool, and if accompanied by sensation of urgency, this is commonly associated with a weaker external voluntary muscle. It is important to ask about constipation and straining, as those who have severe constipation or incomplete emptying of stool may be experiencing overflow incontinence. If there is complete loss of stool without the knowledge of passing anything, this could be overflow incontinence with underlying constipation or impaction, or loss of rectal sensation or internal anal sphincter control caused by neurologic factors. Furthermore, it is important to distinguish between true incontinence and diarrhea because some patients may equate diarrhea with incontinence.

The treatment of fecal incontinence mainly depends on the degree of distress a patient is experiencing from his/her symptoms. Although the patient’s subjective symptoms are important to consider when the clinician is formulating a treatment plan, it is helpful to quantify the severity of incontinence in an objective manner. Several grading scales are available for the clinician to assess the degree of symptoms. Most use a numeric rating scale that allows patients to indicate the frequency of episodes (ie, monthly, weekly, daily, more than daily) and the type of incontinence (solid stool, liquid stool, or gas). The most commonly used scale in clinical practice is the Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence (CCF-FI) Scale (Table 1).7 The scale takes into account the frequency of the incontinence, the type of incontinence (solid stool, liquid, or gas), the use of a pad, and the impact on daily living. Scoring for the scale ranges from 0 to 20. Patients with a score below 8 have mild incontinence; 9 to 14, moderate incontinence; and 15 to 20, severe incontinence. A score of 9 or higher has been associated with a negative impact on quality of life. The severity of fecal incontinence can also be assessed by its impact on quality of life and emotional well-being of the patient. Two other useful scales are the Fecal Incontinence Severity Index, a weighted scoring of symptom frequency, and the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale, which accounts for the impact on quality of life from fecal incontinence symptoms.8,9 The Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale uses 29 questions divided into the 4 scales of lifestyle, coping/behavior, depression/self-perception, and embarrassment. Any type of validated measure can be helpful to provide the physician a better sense of symptom severity and to track improvement after medical and surgical treatment. A patient diary of bowel habits and episodes of incontinence can also be helpful in assessing the severity of symptoms and is a more reliable assessment than patient verbal self-reporting.10

Table 1.

Cleveland Clinic Florida fecal incontinence scorea

| Type of incontinence | Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Rarely (< 1/month) | Sometimes (< 1/week to > 1/month) | Usually (< 1/day to > 1/week) | Always (≥1/day) | |

| Solid | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Liquid | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Gas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Wears pad | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Lifestyle alteration | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993 Jan;36(1):77–97. Reprinted with kind permission of the author (SDW) and Springer Science & Business Media: Diseases of the Colon and Rectum.

The physical examination should focus on the perineum and perianal region, evaluating for normal musculature, bulk of the perineal body, skin condition, and presence of any prolapsing tissue from the anus. Anal problems such as large prolapsing hemorrhoids or rectal prolapse can contribute to fecal incontinence due to stenting open of the anal canal. Some patients may have the appearance of generalized atrophy of the pelvic floor muscles, which may be visualized externally as wasting of the gluteus muscles. Digital rectal examination should be done to evaluate resting tone of the anal muscles, which correlates with internal sphincter muscle tone, and then strength of the squeeze, which correlates with external sphincter muscle strength. The use of accessory buttock muscles can be noted in patients with fecal incontinence when they are asked to squeeze the anal sphincter muscles. Finally, a basic perianal skin sensory assessment is conducted by touching the patient with dull and sharp objects (such as a soft cotton swab and edge of a paper clip) to evaluate whether the patient can distinguish between these sensations.

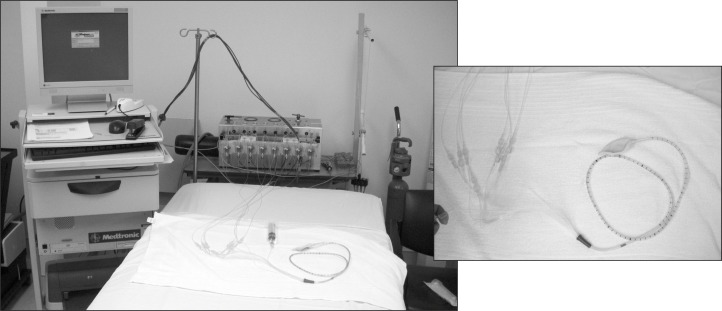

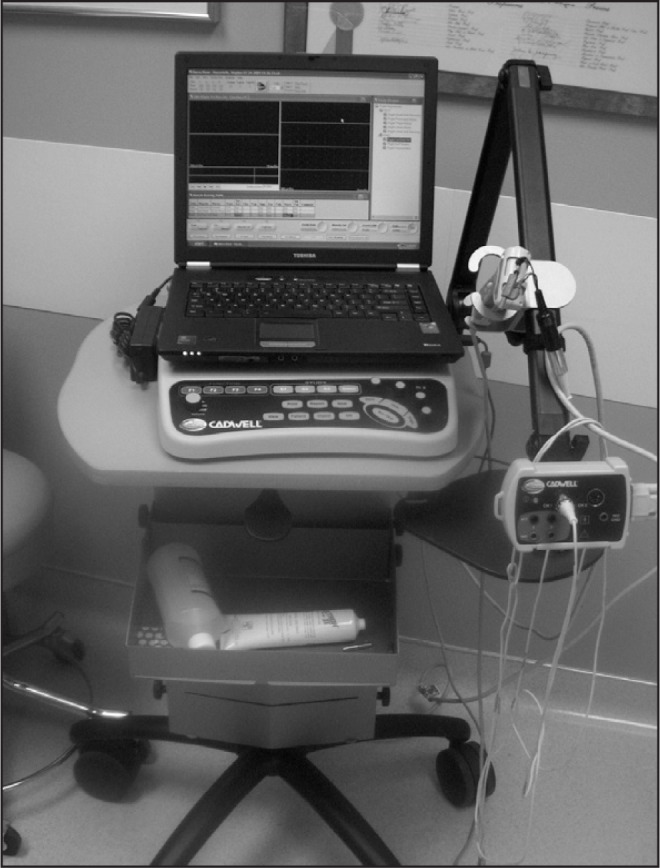

A thorough history and physical examination provide the necessary information to formulate conservative management, but physiologic pelvic floor testing can be very helpful in patients in whom medical management failed and in those being considered for surgical intervention. Pelvic floor testing typically is conducted by specialists in colorectal surgery, urogynecology, gastroenterology, and/or neurology depending on the resources and expertise available in a particular institution. Anal manometry is performed to objectively measure the resting and squeeze pressure of the anal muscles and to assess rectal compliance (Figure 5). A soft catheter with a balloon attached to its tip is introduced through the anus and advanced into the rectum. The anal muscle resting and squeeze pressures are assessed at various levels in the anal canal. Rectal sensation and compliance is measured by filling the balloon with fluids and determining the volume needed to illicit the initial sensation of rectal pressure and the maximum volume tolerated by the patient. In patients with suspected pelvic floor dysfunction, such as incomplete stool evacuation, a balloon expulsion test can be performed at the end of the procedure. Testing of the pudendal nerve, which innervates the anal musculature, can be performed by checking for terminal motor latency of the pudendal nerve and by checking anal electromyography to assess muscle denervation and atrophy (Figure 6). Anal endosonography is useful to assess for sphincter defects, especially in patients with prior vaginal childbirths and those with a history of an anal operation or trauma (Figure 7).

Figure 5.

A (left) Setup for anorectal manometry. B (above) Catheter with balloon at tip for anorectal manometry.

Figure 6.

Setup for pudendal nerve motor latency and anal electromyography testing.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional pelvic ultrasound machine.

Treatment

Various treatments are available to treat fecal incontinence and generally are divided into conservative management and surgical interventions. Conservative management includes dietary modifications, medical management, and physical therapy. The following is a brief overview of some of the treatment options.

Conservative Management

Medical and Dietary Management

The continence mechanism is influenced by pelvic floor and anal musculature as well as the bowel function and habits. The frequency and consistency of stool can greatly affect the severity of symptoms in patients with fecal incontinence. Therefore, one of the most important aspects of fecal incontinence treatment is patient education on bowel function and diet. Dietary modifications play a major role, and many patients can find relief of their symptoms by implementing dietary modifications. Patients are instructed to maintain a diary of food intake and bowel habits for two to three months. The goal is to identify any association between food products and symptoms. Often patients can identify certain foods that trigger incontinence and others that seem to improve the symptoms. Although no two patients are alike, certain foods are associated with worsening of incontinence. Caffeine can trigger fecal incontinence in some patients by relaxing the anal sphincter muscles. Dairy products, especially in lactose-intolerant patients, can worsen the symptoms of patients. Certain vegetables and fruits (eg, figs, cabbage, beans, and chili) can loosen the stools, increase gas production, and increase the frequency and severity of incontinence. Greasy and oily foods, artificial sweeteners, sorbitol and fructose, magnesium-based supplements, and some sugarless gum can trigger incontinence in some patients. Eliminating some of these substances can improve stool quality and control. High fiber, particularly soluble fiber in dietary or supplemental form, can be helpful by bulking and firming stools.11,12 Psyllium-based fiber supplementation can be helpful, and available products on the market include Konsyl and Metamucil. For patients with flatulence issues, psyllium may lead to more gas production and bloating. Alternative nonpsyllium-based products include methylcellulose (Citrucel) and calcium polycarbophil (Fibercon). It is important to note that whereas fiber supplementation can improve the symptoms of some patients, in some it may provide no relief or even exacerbate the incontinence. Therefore, a fiber trial of one to two weeks can be done to assess the response of an individual patient.

A review of a patient’s medications is necessary in the evaluation of patients with fecal incontinence. Several medications can worsen the frequency and severity of the symptoms. Nitrates and calcium channel blockers can decrease sphincter tone, whereas metformin and some antacids can lead to loose stools.13 Excess vitamin and mineral supplementation can loosen stools. Long-term laxative use can lead to incontinence in some patients. A careful review of the medications and supplements list should be conducted during the initial evaluation, and an adjustment of the medications should be considered when appropriate and indicated.

Medical therapy includes antidiarrheal agents, such as loperamide (Imodium), which can slow down transit time and decrease frequency of loose stools.14 It is best taken before meals. Patients are advised to start with 2 mg once a day before breakfast (if incontinent episodes are in the morning) or lunch or dinner (if incontinent episodes later in the day). Other medications that can be of benefit include amitriptyline, which decreases rectal contractions, and low-dose clonidine, which may reduce rectal sensation and urgency by its α-adrenergic effect.15 Postcholecystectomy diarrhea can be successfully treated with cholestyramine, a bile acid sequestrant.

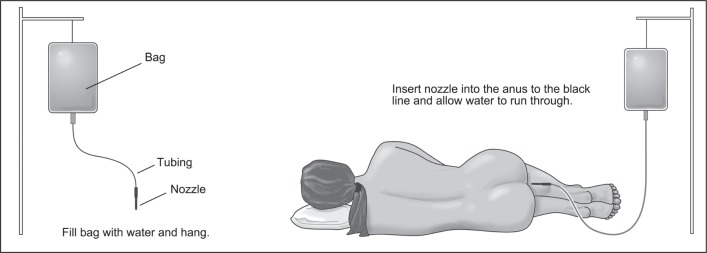

Other helpful measures for symptom control include bowel training, in which one sits on the toilet to pass stool at the same time each day, perhaps consistently after a meal to coordinate with timing of the gastrocolic reflex. This essentially is to regulate the colon into a pattern of defecation. It must be emphasized to the patient that managing the consistency of stool is an important factor, as most patients recognize that fecal incontinence is more frequent when the stools are looser. On the other hand, those who have constipation or incomplete evacuation may benefit from the use of gentle laxatives such as polyethylene glycol (MiraLAX), suppositories, or enemas. Patients with severe evacuation and postdefecation stool incontinence can use daily rectal irrigation to help with colon evacuation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Rectal irrigation set.

Biofeedback

Biofeedback involves pelvic floor and anal sphincter exercises performed under the guidance of an experienced practitioner, usually a physical therapist or a nurse trained in the biofeedback technique. The patient initially receives instructions about the exercises and then performs the exercises with a biofeedback probe inserted in the anal canal. Visual feedback is provided on a screen as the patient performs the exercises. A small biofeedback unit can also be provided to the patient to perform the exercises at home. The exercises are structured to increase strength and endurance of the anal musculature and improve rectal sensation. Some centers will add electrical stimulation to the anal sphincter, although this is of unclear benefit.16 Biofeedback is inexpensive, low risk, and easily tolerated by most patients, and success rates can be as high as 100%.17,18

Surgical Options

Surgical intervention is reserved for patients who have anatomical defects, pathologic conditions that can be corrected surgically, and those in whom conservative management has failed. Patients with pseudoincontinence related to large prolapsing internal hemorrhoids (Figure 9), draining anal fistula, or anorectal tumor can benefit from the appropriate surgical intervention indicated for their condition. Patients with full-thickness rectal prolapse and incontinence can be successfully treated with prolapse repair, although resolution of fecal incontinence is not universal because of other contributory factors (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Patient with large prolapsing hemorrhoids and pseudoincontinence.

Figure 10.

Patient with full-thickness rectal and vaginal prolapse.

Sphincter repair (termed overlapping sphincteroplasty) can be beneficial in patients with anal sphincter defect secondary to traumatic childbirth or prior anal surgery, by restoring the anatomical integrity of the sphincter complex and thereby providing symptomatic improvement (Figure 11). Sphincter repair typically is performed with the patient under a general anesthetic and requires a short hospitalization with several weeks of recovery. Risks of the procedure include infection, bleeding, pain, dyspareunia, and fistula to the vagina. Although the majority of patients find improvement shortly after recovery from the surgery, long-term worsening of symptoms can occur after sphincter repair, as evidenced by a systematic review of 16 studies with 900 patients.19 Short-term loss of efficacy has been previously described in a study of 86 patients.20 Forty-two (49%) of the patients had complete fecal continence after repair, but during a mean follow-up of 40 months, only 21 (28%) of the patients had perfect continence.20 Long-term loss of efficacy was also reported in a study of 191 patients.21 During a 10-year follow-up, many patients reported recurrence of symptoms and 57% of the patients were incontinent. Older age has been associated with a worse functional outcome, as reported by several studies, including a large retrospective review from the Cleveland Clinic.22

Figure 11.

Anal sphincter repair in a patient with prior traumatic childbirth injury.

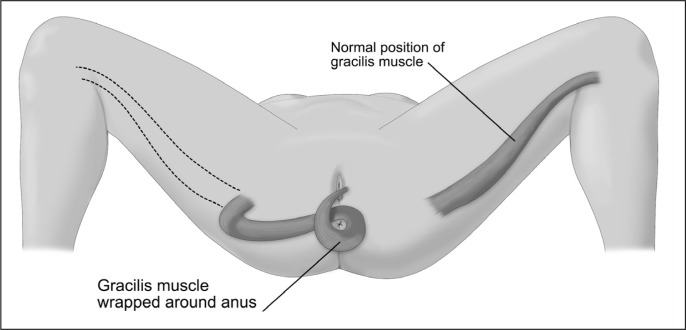

The gracilis muscle runs along the inner medial aspect of the thigh and is of minimal functional significance. Patients with severe fecal incontinence can benefit from graciloplasty, a procedure that entails disconnecting the gracilis muscle attachment at the knee and rotating the muscle toward the perineum, where it is used to wrap the anal sphincter muscle to create a neosphincter (Figure 12). The neosphincter then requires the implantation of a nerve stimulator to enhance the functional tone of the muscle. Although this procedure can provide great relief to the patient, it has been associated with substantial morbidity. In a single institutional study of 38 patients, 24 patients reported pain, swelling, and paresthesia in the donor leg. Among the 22 patients who later maintained a functioning graciloplasty, 11 (50%) reported obstructive defecation.23 Furthermore, 10 patients (27%) required conversion to colostomy during the study period for ongoing fecal incontinence or obstructed defecation. In a multicenter study including 128 patients, the success rate was 66%, with wound complications occurring in one-third of the patients.24 The stimulator graciloplasty is no longer performed in the US because of the unavailability of the muscle stimulator.

Figure 12.

Illustration of a gracilis flap rotation to reach the perineal area for anal sphincter muscle repair.

In addition to use of the patient’s own tissue (ie, gracilis flap) to create a new anal sphincter, 2 artificial bowel sphincters have been studied in patients with severe fecal incontinence. A silicone-based artificial bowel sphincter (Acticon, American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN) can be helpful in alleviating the patient’s symptoms (Figure 13). This device has 3 components, including a cuff that is wrapped around the anus, a fluid reservoir that is implanted in the lower part of the abdominal wall, and a pump control mechanism that is placed inside the scrotum in men or the labia in women. At baseline, the anal cuff is closed and provides continence. When the patient is ready to defecate, the patient squeezes the pump to allow fluid passage from the cuff to the reservoir, resulting in cuff deflation. Within minutes, the cuff refills automatically to provide continence. The device can be very effective at controlling fecal incontinence. However, it has been associated with severe complications, including erosion, infection, and malfunction of the device. One study reported a 50% revision rate (26 of 52 patients), and in 14 (26.9%) of the patients the device was explanted during the study period.25 More recently, a magnetic anal sphincter device (Fenix, Torax Medical, Shoreview, MN) was studied in 14 patients.26 The sphincter is made of titanium beads with magnetic cores and is implanted around the sphincter complex (Figure 14). Two patients reported perfect continence at 1-year follow-up, but 3 patients lost the device, 2 because of infection. In 2 separate matched cohort studies, a portion of this patient cohort was matched to a cohort of women who had undergone either implantation of the silicone artificial bowel sphincter or sacral nerve stimulation (discussed later in this article).27,28 The magnetic anal sphincter was comparable in outcome to the other 2 modalities when assessed for improvement of fecal incontinence severity, quality of life, and resting anal pressures. At this stage, the magnetic anal sphincter is experimental and is not available on the market, and its use is restricted to the few centers involved in research trials.

Figure 13.

Acticon artificial bowel sphincter.

Reprinted with permission from American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, MN.

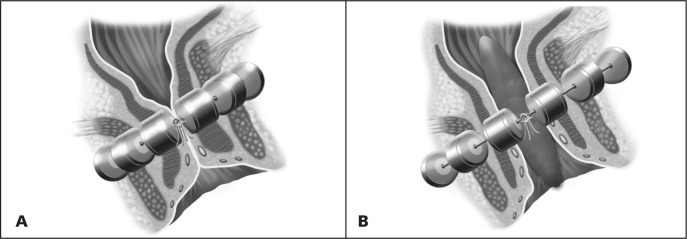

Figure 14.

A (left) In the closed position (at rest) Fenix magnetic bowel sphincter provides continence. B (right) Fenix magnetic bowel sphincter expands with straining to allow voluntary passage of stool.

Reprinted with permission from Torax Medical, Shoreview, MN.

Several bulking agents have been described and are directly injected into either the anal submucosa or the intersphincteric space. The mechanism of bulking agents is to provide a passive increase in resting tone to compensate for decreased internal sphincter tone. Silicone biomaterial (PTQ, Uroplasty BV, Geleen, The Netherlands) is one of the agents that has been frequently used. In a prospective study evaluating PTQ injection, 82 patients experienced symptom improvement, which continued up to 12 months after injection.29 In that study, patients in whom the injection was performed under ultrasound guidance did better than patients whose procedure did not involve ultrasound guidance. A prospective study of carbon-coated microbeads (Durasphere, Coloplast, Minneapolis, MN) analyzed 33 patients, with median follow-up of 21 months.30 Improvement in fecal incontinence symptoms was noted with an associated increase in resting and squeeze pressures on anal manometry, but no improvement in disease-specific quality of life was appreciated. A small randomized clinical trial compared PTQ with Durasphere in 40 patients.31 The PTQ group had no complications, but 8 patients (20%) in the Durasphere group experienced side effects, including pain, erosion, and hypersensitivity reaction. Although both groups showed improvement during a 6-month follow-up, a greater percentage of the PTQ recipients achieved significant improvement in symptoms.26,31 A Cochrane review of trials of injectable bulking agents identified 4 randomized trials.32 The interpretation of these studies was considered limited because of bias and short-term follow-up. However, the silicone bioinjectable agent appeared safer than carbon-coated beads.32 A systematic review of injectable bulking agents analyzed 1070 patients pooled from 39 publications and concluded that PTQ silicone injection was overall more effective than other types of injectables.33 A more recently studied injectable agent is dextranomer hyaluronic acid (Solesta, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Raleigh, NC), which is injected submucosally in 4 anal quadrants above the dentate line. A randomized sham-controlled trial in 278 patients demonstrated that 52% of patients who received the injectable product experienced 50% or greater improvement in the number of incontinence episodes compared with 32% in the sham group.34 This agent was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and is available to patients.

The Secca procedure (Mederi Therapeutics, Greenwich, CT) entails the delivery of radiofrequency energy to the internal sphincter muscle (Figure 15). This procedure is believed to induce scarring and collagen contraction and deposition, which lead to tightening of the internal sphincter muscle. The procedure was initially studied prospectively in 10 women.35 At 2-year follow-up, subjects had significant improvement in incontinence severity scores. The mean CCF-FI score decreased from 13.8 to 7.3, and 9 patients experienced improvement of symptoms. Efron and colleagues36 conducted a multicenter trial that enrolled 50 patients. Significant improvement in the CCF-FI score was noted at 6 months, decreasing from 14.5 to 11.1. A recent study by Abbas and colleagues37 examined the outcome of the Secca procedure in 27 patients. Most patients had failed to improve after biofeedback or other types of surgical intervention. Short-term improvement was noted in 21 patients (78%) at 3 months. However, during a mean follow-up of 40 months, only 6 (22%) of the patients had a sustained effect and 14 (52%) of the patients had undergone or were awaiting additional surgical intervention.37

Figure 15.

Secca radiofrequency energy device.

Reprinted with permission from Mederi Therapeutics, Greenwich, CT.

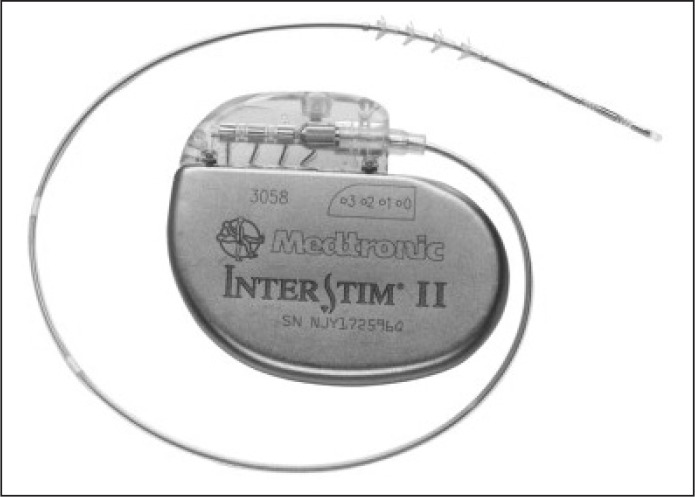

A sacral nerve stimulator (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of fecal incontinence in the US (Figure 16). Sacral nerve stimulation was initially used to treat patients with urinary incontinence. The treatment entails 2 procedures: an initial implantation of a percutaneous lead in the third sacral foramen with a brief trial (typically 1 to 2 weeks), followed by the implantation of the permanent device. During the test period, the patient maintains a diary recording the frequency of episodes of incontinence. An improvement of 50% or more in the patient’s symptoms leads to the implantation of the device, which typically has a battery life of 3 to 5 years depending on the degree of stimulation. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated good long-term outcome in appropriate candidates.38,39 Although the mechanism of action of sacral nerve stimulation is not entirely clear, patients report fewer episodes of incontinence and decreased urgency. A US-based, randomized controlled trial with a 3-year follow-up demonstrated improvement of symptoms in 86% of the 133 enrolled patients.40 Additional research is being conducted to determine predictors of long-term success in order to improve patient selection for this therapy. Complications of sacral nerve stimulation include pain, infection, seroma formation, bleeding, and scarring.

Figure 16.

Sacral nerve stimulator.

Reprinted with permission from Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN.

More recently, posterior tibial nerve stimulation has been investigated.41 Similar to sacral nerve stimulation, posterior tibial nerve stimulation has been used in patients with urinary incontinence. It involves an office-based procedure, which involves repeated electrical stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve by needle insertion. The exact mechanism of action is not clear. One prospective study of 31 patients with urge fecal incontinence reported improvement in 21 patients (68%) during a median follow-up of 9 months.41

Patients with severe fecal incontinence in whom all conservative and surgical treatments fail can undergo fecal diversion as a last resort. A diverting colostomy is reserved for patients with poor quality of life. A laparoscopic approach is advised to minimize the risks of abdominal surgery and to provide a rapid recovery. Although many patients may be reluctant to have a permanent stoma initially, the improvement in quality of life can be substantial.

Conclusions

Fecal incontinence is a potentially debilitating condition that can lead to depression and social isolation. Initial evaluation and screening can be performed by the primary care physician, and conservative management can be instituted with good success in many patients. Dietary modifications, adjustment of medications, and a trial of biofeedback should be the first line of therapy in most patients. Patients with severe fecal incontinence and those in whom conservative management fails can be referred for further evaluation by a colorectal surgeon and/or urogynecologist. Patients with gastrointestinal disorders contributing to incontinence should be evaluated first by a gastroenterologist.

Several surgical options are currently available to treat fecal incontinence and should be individualized on the basis of degree and type of symptoms, the cause of the incontinence, and patient-related factors. These options vary from local anal sphincter repair, injectables, and radiofrequency energy treatment to implantable devices such as the sacral nerve stimulator and artificial bowel sphincter. The surgical management of fecal incontinence will undoubtedly continue to evolve as innovations bring new devices and therapies to health care.

Acknowledgments

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications, Inc, provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Worth More To Man

I hav finally kum to the konklusion that a good reliable sett ov bowels iz wurth more tu a man, than enny quantity ov brains.

— Henry Wheeler Shaw (“Josh Billins”), 1818–1885, 19th-century American humorist

References

- 1.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr;53(4):629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quander CR, Morris MC, Melson J, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Prevalence of and factors associated with fecal incontinence in a large community study of older individuals. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Apr;100(4):905–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30511.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitehead WE, Borrud L, Goode PS, et al. Pelvic Floor Disorders Network Fecal incontinence in US adults: epidemiology and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2009 Aug;137(2):512–7. 517.e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.054. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perry S, Shaw C, McGrother C, et al. Leicestershire MRC Incontinence Study Team Prevalence of faecal incontinence in adults aged 40 years or more living in the community. Gut. 2002 Apr;50(4):480–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.480. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.50.4.480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook TA, Mortensen NJ. Management of faecal incontinence following obstetric injury. Br J Surg. 1998 Mar;85(3):293–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00693.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varma MG, Brown JS, Creasman JM, et al. Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Study at Kaiser (RRISK) Research Group Fecal incontinence in females older than aged 40 years: who is at risk? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006 Jun;49(6):841–51. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993 Jan;36(1):77–97. doi: 10.1007/BF02050307. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999 Dec;42(12):1525–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Jan;43(1):9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02237236. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02237236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher K, Bliss DZ, Savik K.Comparison of recall and daily self-report of fecal incontinence severity J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2008September–Oct355515–20.DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.WON.0000335964.13855.8d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eherer AJ, Santa Ana CA, Porter J, Fordtran JS. Effect of psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and wheat bran on secretory diarrhea induced by phenolphthalein. Gastroenterology. 1993 Apr;104(4):1007–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90267-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wenzl HH, Fine KD, Schiller LR, Fordtran JS. Determinants of decreased fecal consistency in patients with diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1995 Jun;108(6):1729–38. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90134-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(95)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton C, Whitehead WE, Bliss DZ, Harari D, Lang J, Conservative Management of Fecal Incontinence in Adults Committee of the International Consultation on Incontinence Management of fecal incontinence in adults. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):199–206. doi: 10.1002/nau.20803. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nau.20803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palmer KR, Corbett CL, Holdsworth CD. Double-blind cross-over study comparing loperamide, codeine and diphenoxylate in the treatment of chronic diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 1980 Dec;79(6):1272–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malcolm A, Camilleri M, Kost L, Burton DD, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Towards identifying optimal doses for alpha-2 adrenergic modulation of colonic and rectal motor and sensory function. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000 Jun;14(6):783–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00757.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosker G, Cody JD, Norton CC. Electrical stimulation for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007. Jul 18, p. CD001310. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001310.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Lacima G, Pera M, Amador A, Escaramis G, Piqué JM. Long-term results of biofeedback treatment for faecal incontinence: a comparative study with untreated controls. Colorectal Dis. 2010 Aug;12(8):742–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01881.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norton C, Chelvanayagam S, Wilson-Barnett J, Redfern S, Kamm MA. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003 Nov;125(5):1320–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow SC, Lowry AC. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012 Apr;55(4):482–90. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182468c22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182468c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karoui S, Leroi AM, Koning E, Menard JF, Michot F, Denis P. Results of sphincteroplasty in 86 patients with anal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000 Jun;43(6):813–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02238020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02238020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bravo Gutierrez A, Madoff RD, Lowry AC, Parker SC, Buie WD, Baxter NN. Long-term results of anterior sphincteroplasty. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 May;47(5):727–32. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0114-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-003-0114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Hannaway C, Gurland B, Hull T. Overlapping sphincter repair: does age matter? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012 Mar;55(3):256–61. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823deb85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823deb85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thornton MJ, Kennedy ML, Lubowski DZ, King DW. Long-term follow-up of dynamic graciloplasty for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2004 Nov;6(6):470–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00714.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madoff RD, Rosen HR, Baeten CG, et al. Safety and efficacy of dynamic muscle plasty for anal incontinence: lessons from a prospective, multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1999 Mar;116(3):549–56. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70176-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong MT, Meurette G, Wyart V, Glemain P, Lehur PA. The artificial bowel sphincter: a single institution experience over a decade. Ann Surg. 2011 Dec;254(6):951–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823ac2bc. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823ac2bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lehur PA, McNevin S, Buntzen S, Mellgren AF, Laurberg S, Madoff RD. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a preliminary report from a feasibility study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Dec;53(12):1604–10. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f5d5f7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f5d5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong MT, Meurette G, Wyart V, Lehur PA. Does the magnetic anal sphincter device compare favourably with sacral nerve stimulation in the management of faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis. 2012 Jun;14(6):e323–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02995.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong MT, Meurette G, Stangherlin P, Lehur PA. The magnetic anal sphincter versus the artificial bowel sphincter: a comparison of 2 treatments for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Jul;54(7):773–9. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182182689. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182182689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tjandra JJ, Lim JF, Hiscock R, Rajendra P. Injectable silicone biomaterial for fecal incontinence caused by internal anal sphincter dysfunction is effective. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 Dec;47(12):2138–46. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0760-3. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-0760-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altomare DF, La Torre F, Rinaldi M, Binda GA, Pescatori M. Carbon-coated microbeads anal injection in outpatient treatment of minor fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008 Apr;51(4):432–5. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9170-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-007-9170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK, Yeh HC. Injectable silicone biomaterial (PTQ) is more effective than carbon-coated beads (Durasphere) in treating passive faecal incontinence—a randomized trial. Colorectal Dis. 2009 May;11(4):382–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01634.x. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda Y, Laurberg S, Norton C. Perianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010. May 12, p. CD007959. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007959.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Hussain ZI, Lim M, Stojkovic SG. Systematic review of perianal implants in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2011 Nov;98(11):1526–36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7645. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel KE, Hull T, Johansson C, Bernstein M, NASHA Dx Study Group Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011 Mar 19;377(9770):997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62297-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi T, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos MA, Belmonte C, Barreto C, Velasco L. Extended two-year results of radio-frequency energy delivery for the treatment of fecal incontinence (the Secca procedure) Dis Colon Rectum. 2003 Jun;46(6):711–5. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6644-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-004-6644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Efron JE, Corman ML, Fleshman J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of temperature-controlled radio-frequency energy delivery to the anal canal (Secca procedure) for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003 Dec;46(12):1606–18. doi: 10.1007/BF02660763. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02660763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbas MA, Tam MS, Chun LJ. Radiofrequency treatment for fecal incontinence: is it effective long-term? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012 May;55(5):605–10. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182415406. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182415406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leroi AM, Parc Y, Lehur PA, et al. the Study Group Efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: results of a multicenter double-blind crossover study. Ann Surg. 2005 Nov;242(5):662–9. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000186281.09475.db. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000186281.09475.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matzel KE, Kamm MA, Stösser M, et al. Sacral spinal nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence: multicentre study. Lancet. 2004 Apr 17;363(9417):1270–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15999-0. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15999-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellgren A, Wexner SD, Coller JA, et al. SNS Study Group Long-term efficacy and safety of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011 Sep;54(9):1065–75. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822155e9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e31822155e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boyle DJ, Prosser K, Allison ME, Williams NS, Chan CL. Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation for the treatment of urge fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 Apr;53(4):432–7. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c75274. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181c75274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]