Abstract

The antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent 5-fluorouracil is used to treat a variety of cancers. Although 5-fluorouracil is generally well tolerated, its toxicity profile includes potential cardiac ischemia, vasospasm, arrhythmia, and direct myocardial injury. These actual or potential toxicities are thought to resolve upon cessation of the medication; however, information about the long-term cardiovascular effects of therapy is not sufficient. We present the case of a 58-year-old man who had 2 ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrests, with evidence of coronary vasospasm and myocarditis, on his 4th day of continuous infusion with 5-fluorouracil. External defibrillation and cessation of the 5-fluorouracil therapy resolved the patient's electrocardiographic abnormalities. In addition to reporting the clinical manifestations of 5-fluorouracil–associated cardiotoxicity in our patient, we discuss management challenges in patients who develop severe 5-fluorouracil–induced ventricular arrhythmias.

Key words: Arrhythmias, cardiac/chemically induced; coronary vasospasm/chemically induced; fluorouracil/adverse effects; heart/drug effects; heart diseases/drug therapy; myocarditis/chemically induced; treatment outcome

Chemotherapeutic agents have greatly improved the overall prognosis of patients with various cancers. Nevertheless, these drugs can have severe and sometimes life-threatening side effects. The cardiovascular complications can be particularly dramatic. One such agent, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), interferes with DNA synthesis in cancer cells, leading to cell death. It is used to treat a variety of malignancies, including gastrointestinal, esophageal, bladder, and head and neck cancers.1 Its severe cardiotoxic effects include vasospasm, ischemia, arrhythmias, and myopathic processes. We report the case of a patient who survived ventricular fibrillation (VF) cardiac arrest attributed to 5-FU–induced vasospasm and myocarditis. This case suggests that the multiple cardiotoxic effects of 5-FU can occur simultaneously and might be interrelated. In addition, we discuss management challenges in this patient population.

Case Report

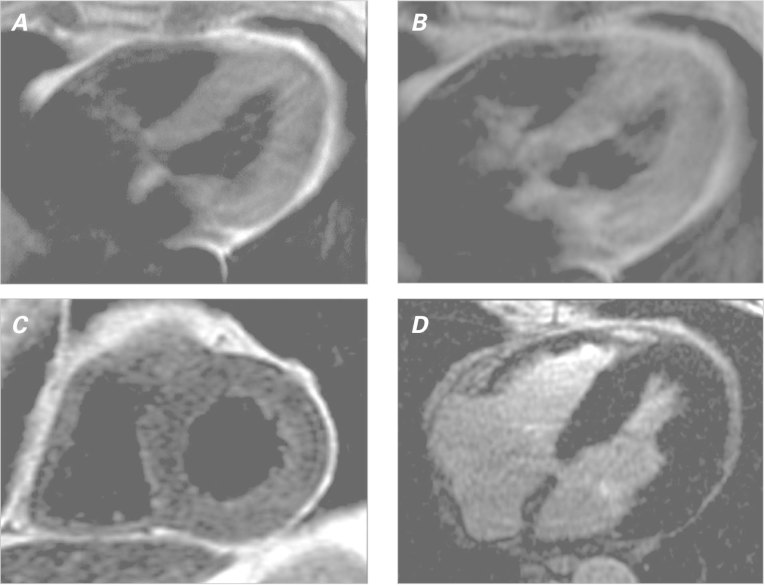

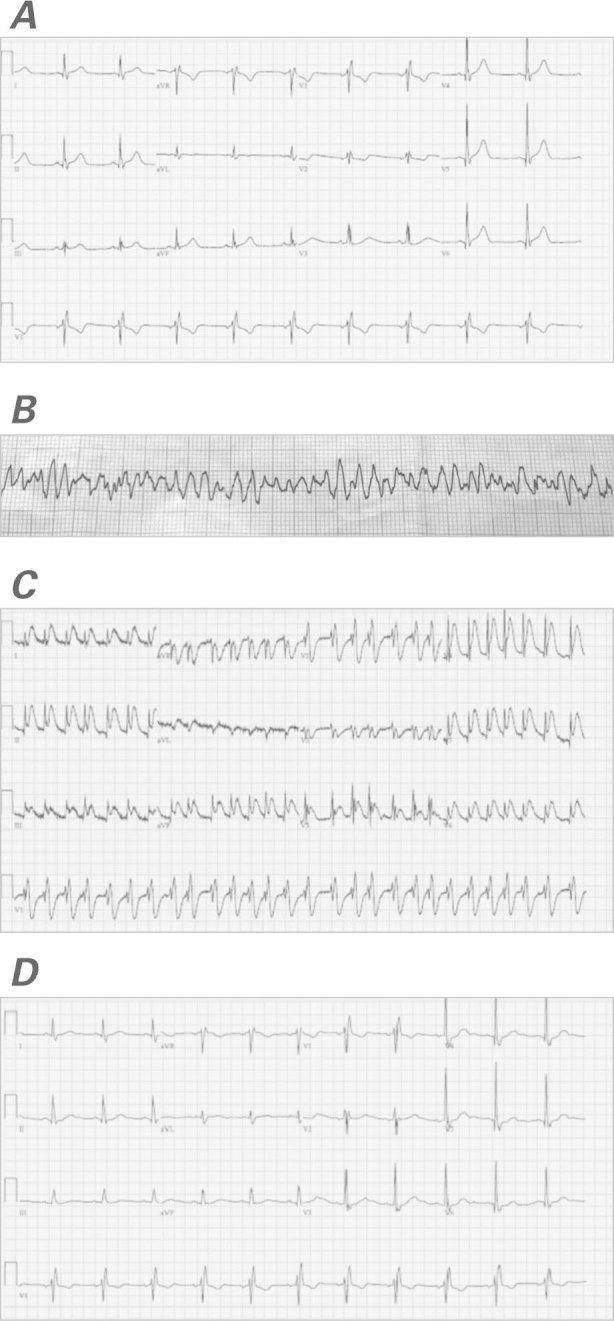

In September 2011, a 58-year-old man with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia was diagnosed with a locally advanced, but potentially curable, T2N2cM0 non-keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma of the base of the tongue. Because of the patient's high-grade adenopathy, his oncologists recommended initial induction chemotherapy, before radiation therapy. He was started on a standard regimen of induction cisplatin, docetaxel, and 5-FU. On the 3rd day of therapy with continuously infused 5-FU, the patient reported an episode of chest discomfort. More severe chest pain on the 4th day prompted referral to our emergency department. Upon evaluation, the patient's troponin T level was mildly elevated at 0.3 μg/L. A baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus bradycardia with normal ST segments and a normal QT interval (Fig. 1A). While under emergency care and still on 5-FU infusion, the patient developed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response. He then became unresponsive and was found to be in pulseless polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that rapidly degenerated into VF (Fig. 1B). He was given cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation at 200 J. A subsequent ECG revealed atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and transient ST elevations in the anterior and inferior leads (Fig. 1C). While awaiting transfer to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, the patient had another VF arrest that necessitated CPR and defibrillation. Coronary angiograms showed no obstructive coronary lesions (Fig. 2), and there was no evidence of epicardial coronary vasospasm. After our consultation with the medical oncology team, the 5-FU infusion was discontinued.

Fig. 1 Electrocardiograms show A) sinus bradycardia, a normal ST segment, and a normal QT interval (at baseline); B) ventricular fibrillation (upon emergent presentation); C) atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and ST-segment elevation in the anterior and inferior leads (after first defibrillation); and D) sinus rhythm with resolution of the ST-segment elevation (upon the patient's discharge from the hospital).

Fig. 2 Coronary angiograms show no obstructive lesions in A) the left anterior descending coronary artery, the left circumflex coronary artery, or B) the right coronary artery.

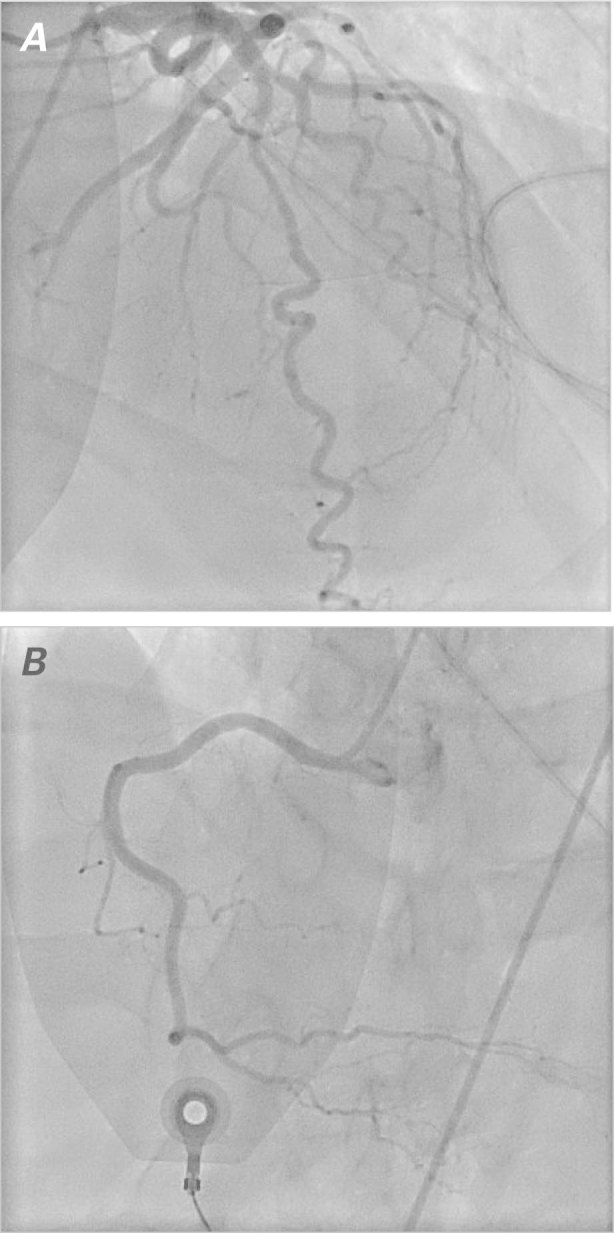

Echocardiograms showed a normal left ventricular ejection fraction (0.74) and mild left ventricular hypertrophy without wall-motion abnormalities or valvular dysfunction. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) images revealed elevated early relative global myocardial enhancement and associated myocardial edema without evidence of focal late gadolinium enhancement, consistent with diffuse myocarditis (Fig. 3).2

Fig. 3 Cardiac magnetic resonance with a myocarditis protocol. Spin-echo T1-weighted images show increased global early myocardial enhancement A) before and B) after gadolinium contrast, yielding an elevated ratio of 6.1 (normal, <4). C) Fast-spin-echo T2-weighted image shows global myocardial edema with an elevated ratio (2.1) of T2 signal in the myocardium compared to skeletal muscle (normal, <2). D) Late-gadolinium-enhancement image shows no focal myocardial fibrosis or injury.

The patient's presentation was attributed to 5-FU cardiotoxicity that manifested itself as coronary vasospasm and toxic myocarditis. He was started on calcium channel blockers and nitrates, with a plan to avoid all forms of 5-FU in the future. After carefully considering the role of device-based therapy, we discharged the patient from the hospital after 4 days with a wearable external cardioverter-defibrillator device. At the time of discharge, an ECG revealed sinus rhythm with normal ST segments (Fig. 1D). One month later, CMR images showed no evidence of myocarditis and yielded no unusual results despite the patient's ongoing therapy with cisplatin and docetaxel. The patient stopped using the external device after one month and, as of July 2013, had no further evidence of ventricular arrhythmias.

Discussion

Adverse cardiovascular events associated with 5-FU therapy were first reported in 1975.3 The prevalence of cardiotoxicity is reportedly from 1.2% to 18%.4 The most frequently reported event is angina pectoris with ischemia, perhaps caused by coronary vasospasm; myocarditis, cardiomyopathies, and arrhythmias have also been described.5–7 Studies have not yet definitively elucidated the mechanism by which 5-FU exerts its cardiotoxic effects. Coronary vasospasm has been observed in rabbit models and in patients during 5-FU infusion8,9; however, another study failed to identify vasospasm in a patient with 5-FU cardiotoxicity who was challenged with ergonovine during cardiac catheterization.10 Alternative theories have implicated autoimmune phenomena or direct thrombogenic effects.11,12 Direct myocardial toxicity leading to diffuse myocarditis has also been identified.6,9 In fact, the myocarditis can present with ischemic ECG changes ranging from T-wave inversions to frank ST elevation that mimics vasospasm.13 The cardiotoxic effects of 5-FU also appear to occur more often in association with continuous infusions than with bolus infusions.7 In our patient, who was given continuously infused 5-FU, we observed multiple cardiovascular complications: angina, diffuse ST elevations, myocarditis, atrial fibrillation, and 2 VF cardiac arrests. This suggests that the cardiotoxic effects of 5-FU are interrelated.

When a patient experiences severe cardiotoxicity, it is evident that 5-FU should be discontinued and the patient should not again be challenged with it. However, because no definitive causative mechanism of 5-FU cardiotoxicity has been identified, the optimal long-term cardiovascular management of such patients is unclear. Medical therapy for coronary vasospasm has classically involved antispasmodic agents such as calcium channel blockers or nitrates; however, they are less efficacious in 5-FU cardiotoxicity.14 This is probably because vasospasm is not the only consequence of 5-FU cardiotoxicity. The investigators in one study suggested that there were no delayed cardiovascular effects of 5-FU15; however, not enough dedicated studies have evaluated this issue, and the long-term cardiovascular effects of 5-FU are unknown. As the number of cancer patients who are exposed to 5-FU continues to increase, the evaluation of long-term sequelae will become even more important.

In view of our patient's dramatic presentation with 2 episodes of VF, it is reasonable to consider the role of device-based therapy in patients with 5-FU cardiotoxicity. The 2008 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac-rhythm abnormalities include a class I indication for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) therapy in survivors of VF cardiac arrest if no reversible cause is identified.16 In view of the vasospastic properties of 5-FU, it is generally thought that patients are no longer at risk of cardiovascular side effects after that therapy is discontinued. Even if 5-FU causes acute myocarditis with associated ischemia and arrhythmias, ICDs are typically offered to patients only after the acute phase, and upon evidence of chronic inflammation and persistent ventricular arrhythmias.17 Investigators in one small study18 found that patients exposed to 5-FU had significantly prolonged QT intervals 3 months after therapy, compared with pre-exposure values; however, the clinical significance of this finding was not determined.

Our patient's presentation led us to recommend that he use an external cardioverter-defibrillator. These devices were developed to treat patients who do not immediately meet criteria for ICD implantation but who are nonetheless at higher risk of sudden cardiac death. The external devices have effectively identified and treated ventricular arrhythmias and have yielded survival rates similar to those in patients with ICDs.19,20 In the presence of 5-FU–associated ventricular arrhythmias and acute myocarditis, they can serve as an effective preventive tool until a long-term treatment plan is devised. Patients with 5-FU–associated ventricular arrhythmias have been given ICDs21; however, until the long-term cardiovascular effects of 5-FU are definitively determined, ICD implantation cannot be generally recommended and should be considered on an individual basis.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Michael G. Fradley, MD, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of South Florida, 2 Tampa General Cir., 5th fl., Tampa, FL 33606

E-mail: mfradley@health.usf.edu

References

- 1.Dalzell JR, Samuel LM. The spectrum of 5-fluorouracil cardiotoxicity. Anticancer Drugs 2009;20(1):79–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: a JACC white paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53(17):1475–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dent RG, McColl I. Letter: 5-Fluorouracil and angina. Lancet 1975;1(7902):347–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tsibiribi P, Descotes J, Lombard-Bohas C, Barel C, Bui-Xuan B, Belkhiria M, et al. Cardiotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil in 1350 patients with no prior history of heart disease. Bull Cancer 2006;93(3):E27–30. [PubMed]

- 5.Stewart T, Pavlakis N, Ward M. Cardiotoxicity with 5-fluorouracil and capecitabine: more than just vasospastic angina. Intern Med J 2010;40(4):303–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sasson Z, Morgan CD, Wang B, Thomas G, MacKenzie B, Platts ME. 5-Fluorouracil related toxic myocarditis: case reports and pathological confirmation. Can J Cardiol 1994;10 (8):861–4. [PubMed]

- 7.Kosmas C, Kallistratos MS, Kopterides P, Syrios J, Skopelitis H, Mylonakis N, et al. Cardiotoxicity of fluoropyrimidines in different schedules of administration: a prospective study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2008;134(1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Luwaert RJ, Descamps O, Majois F, Chaudron JM, Beauduin M. Coronary artery spasm induced by 5-fluorouracil. Eur Heart J 1991;12(3):468–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Tsibiribi P, Bui-Xuan C, Bui-Xuan B, Lombard-Bohas C, Duperret S, Belkhiria M, et al. Cardiac lesions induced by 5-fluorouracil in the rabbit. Hum Exp Toxicol 2006;25(6):305–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Freeman NJ, Costanza ME. 5-Fluorouracil-associated cardiotoxicity. Cancer 1988;61(1):36–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Stevenson DL, Mikhailidis DP, Gillett DS. Cardiotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil. Lancet 1977;2(8034):406–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Gradishar W, Vokes E, Schilsky R, Weichselbaum R, Panje W. Vascular events in patients receiving high-dose infusional 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy: the University of Chicago experience. Med Pediatr Oncol 1991;19(1):8–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Karjalainen J, Heikkila J. Incidence of three presentations of acute myocarditis in young men in military service. A 20-year experience. Eur Heart J 1999;20(15):1120–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Patel B, Kloner RA, Ensley J, Al-Sarraf M, Kish J, Wynne J. 5-Fluorouracil cardiotoxicity: left ventricular dysfunction and effect of coronary vasodilators. Am J Med Sci 1987;294(4):238–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.de Forni M, Malet-Martino MC, Jaillais P, Shubinski RE, Bachaud JM, Lemaire L, et al. Cardiotoxicity of high-dose continuous infusion fluorouracil: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol 1992;10(11):1795–801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Epstein AE, Dimarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for Device-Based Therapy of Cardiac Rhythm Abnormalities: executive summary [published erratum appears in Heart Rhythm 2009;6(1):e1]. Heart Rhythm 2008;5(6):934–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Zipes DP, Camm AJ, Borggrefe M, Buxton AE, Chaitman B, Fromer M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to develop guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death) developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace 2006;8(9):746–837. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Wacker A, Lersch C, Scherpinski U, Reindl L, Seyfarth M. High incidence of angina pectoris in patients treated with 5-fluorouracil. A planned surveillance study with 102 patients. Oncology 2003;65(2):108–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Chung MK, Szymkiewicz SJ, Shao M, Zishiri E, Niebauer MJ, Lindsay BD, Tchou PJ. Aggregate national experience with the wearable cardioverter-defibrillator: event rates, compliance, and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56(3):194–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Feldman AM, Klein H, Tchou P, Murali S, Hall WJ, Mancini D, et al. Use of a wearable defibrillator in terminating tachyarrhythmias in patients at high risk for sudden death: results of the WEARIT/BIROAD. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004;27(1):4–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Shah NR, Shah A, Rather A. Ventricular fibrillation as a likely consequence of capecitabine-induced coronary vasospasm. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2012;18(1):132–5. [DOI] [PubMed]