Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement is an increasingly common treatment of critical aortic stenosis. Many aortic stenosis patients have concomitant left ventricular dysfunction, which can instigate the formation of thrombus resistant to anticoagulation. Recent trials evaluating transcatheter aortic valve replacement have excluded patients with left ventricular thrombus. We present a case in which an 86-year-old man with known left ventricular thrombus underwent successful transcatheter aortic valve replacement under cerebral protection.

Key words: Aortic valve stenosis/therapy; cerebral infarction/etiology; embolic protection devices; heart valve prosthesis implantation; intracranial embolism/prevention & control; stroke/etiology; thrombus, left ventricular

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has given hope to patients with surgically inoperable critical aortic stenosis.1,2 However, the enthusiasm generated by this emerging technology has been tempered by the incidence of both silent and clinically apparent cerebral vascular accidents.2–4 These events can be either atheroembolic (originating from manipulation of the TAVR sheath in a diseased ascending aorta) or thromboembolic (originating from intracardiac chambers or from the aortic valve itself). The presence of left ventricular (LV) thrombus has been shown to be responsible for up to 20% of cardioembolic events in a clinical setting.5,6

According to professional societies, LV thrombus is a contraindication for TAVR; and such thrombus has been an exclusion criterion in clinical trials.7–9 However, a minority of aortic stenosis patients in need of transcatheter valve therapy present with intraventricular thrombus that does not respond to anticoagulation and therefore poses a challenge to the clinician. Evidence to support the optimal treatment of these patients is lacking. We present a case of TAVR in which we used cerebral protection in treating a surgically inoperable patient who had an LV thrombus.

Case Report

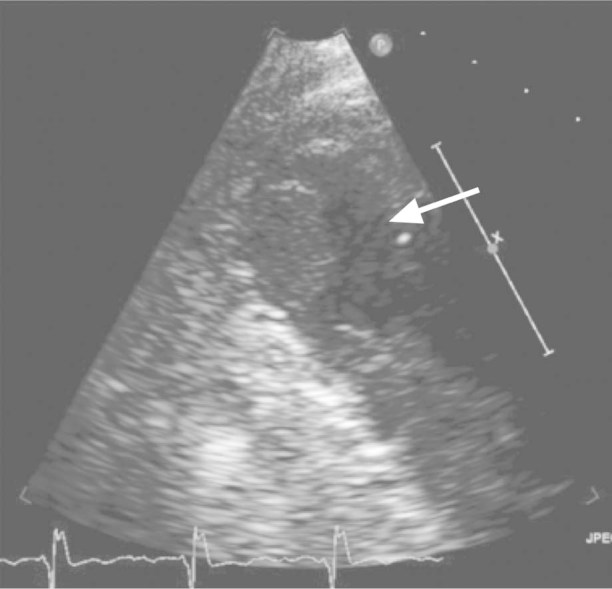

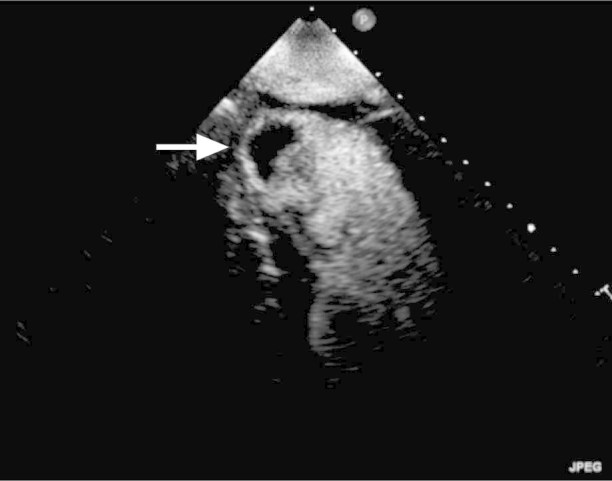

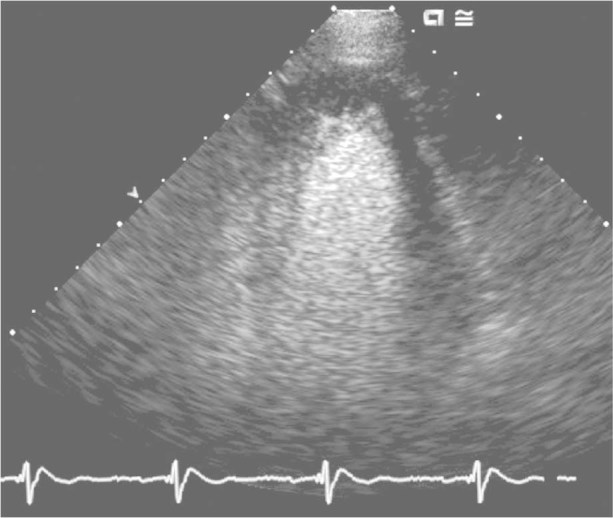

An 86-year-old man with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and of coronary artery bypass surgeries in 1989 and 1999 presented in March 2012 with severe exertional fatigue. He was discovered to have critical aortic stenosis (aortic valve area, 0.4 cm2). Given his age, previous open-heart surgeries, and elevated Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 11.3, he was referred for TAVR. During the initial evaluation, he was found to have an apical LV thrombus and a mildly decreased ejection fraction of 0.50 (Fig. 1). He was referred for cardiac catheterization, which revealed moderate disease of the right coronary artery and a complete mid-segment occlusion of the left circumflex coronary artery. The left anterior descending coronary artery was diffusely diseased beyond the anastomosis of the left internal mammary artery, and it was presumed that the apical thrombus was due to a previous infarct of the LV apex. The patient had previously been anticoagulated with warfarin for atrial fibrillation, and his international normalized ratio levels had been therapeutic. Because of his lack of response to warfarin, he was switched to enoxaparin and scheduled for TAVR. After 6 weeks of therapy, repeat contrast echocardiograms showed persistence of the apical thrombus with no change in size (Fig. 2). Because the patient's functional status was rapidly declining, we decided to proceed with TAVR, aided by an available U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved cerebral embolic protection device.

Fig. 1 Two-dimensional echocardiogram (with contrast), obtained earlier at another hospital, shows the left ventricle with a visible thrombus (arrow).

Fig. 2 Preprocedural 2-dimensional echocardiogram (with contrast) continues to show the 1.3 × 2-cm left ventricular apical thrombus (arrow) despite more than a month of anticoagulation.

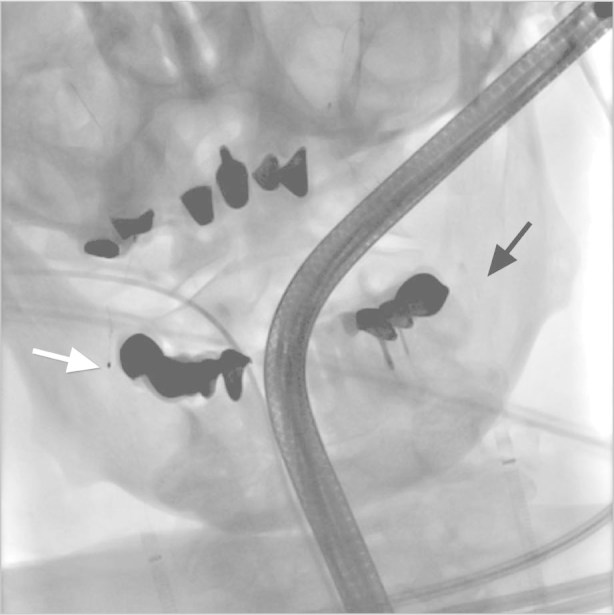

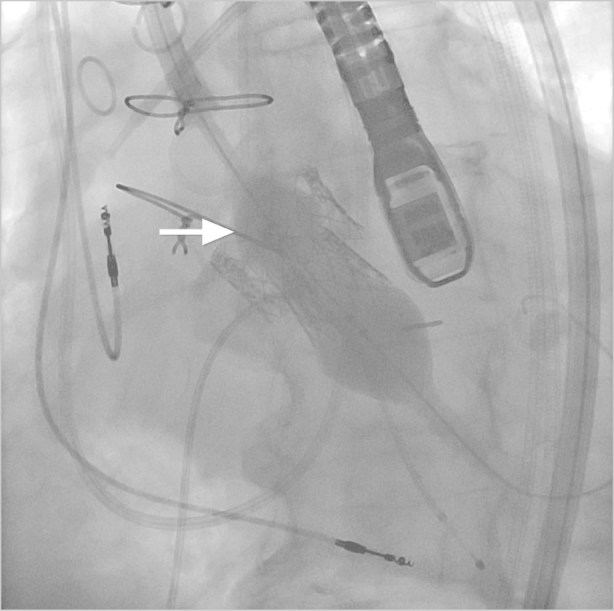

At the beginning of the procedure, we placed 2 sheaths (6F) into the left femoral artery at separate puncture sites, for the delivery of 2 cerebral embolic protection devices. The right femoral artery was used for transcatheter valve delivery, and the radial artery was used to advance a pigtail catheter for the angiographic evaluation of valve positioning. A Spider FX™ Embolic Protection Device (Covidien; Mansfield, Mass) was placed in each internal carotid artery through two 6F Pinnacle® Destination® sheaths (Terumo Medical Corporation; Somerset, NJ) (Fig. 3). Subsequently, a 26-mm SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences Corporation; Irvine, Calif) was placed in the aortic position under transesophageal echocardiographic (TEE) and angiographic guidance. After valve deployment, a substantial paravalvular leak at the noncoronary cusp was noted, in response to which a 2nd valve was deployed. The TEE evaluation after deployment of the 2nd valve revealed minimal residual paravalvular leak (Fig. 4). At the end of the procedure, the cerebral protection devices were removed. Inspection of the devices revealed no evidence of thrombotic material (Fig. 5). Anticoagulation was then performed for 12 hours, at the conclusion of which the patient was started on unfractionated heparin as a bridge to warfarin. The patient had an uneventful hospital stay without focal neurologic deficits and was discharged one week later. Neurologic evaluation at 30-day follow-up revealed a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of zero.10 In addition, he showed marked improvement in his functional capacity, from New York Heart Association class IV to class II. Repeat echocardiograms showed minimal paravalvular aortic regurgitation, improved LV function, and no evidence of apical thrombus (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3 Fluoroscopic view shows the Spider FX devices correctly deployed in the right (white arrow) and the left (black arrow) internal carotid arteries.

Fig. 4 Fluoroscopic view shows the valve-in-valve (arrow) technique used to stop paravalvular leak after placement of the initial valve.

Fig. 5 After deployment and retrieval, the cerebral protection device shows no evidence of thromboembolic material.

Fig. 6 Thirty days after the procedure, a 2-dimensional echocardiogram shows no evidence of the clot.

Discussion

A major safety concern after transfemoral TAVR is the risk of stroke consequent to dislodgment and embolization of débris from aortic arch atheroma or apical thrombus, or from the calcified valve itself. After TAVR, a high proportion of patients display new foci of restricted diffusion on cerebral diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging.5 The use of cerebral protection devices might decrease the risk of stroke in patients undergoing TAVR. A study in a swine model11 has shown the effectiveness of deflector devices by reducing the embolic load (from 19% to 1.3%).

Various types of cerebral protection devices have followed the same general design12: a net made of porous membrane is used to filter emboli in the aorta, thereby protecting the cerebral circulation while enabling continued blood flow—as did the Spider FX device that we deployed. Exceptions to this design include a flat planar snowshoe device placed across the apex of the aorta, in order to prevent emboli from entering the carotid arteries.

Although the use of TAVR has not to our knowledge been reported in patients with intraventricular thrombus, many aortic stenosis patients have concomitant coronary artery disease and LV dysfunction, so the patient population is probably sizable. In our patient, we presume that the final dissolution of the LV thrombus was due to the partial relief of the apical dyskinesis after the aortic valve was replaced. Cerebral protection devices might offer a method of safely performing TAVR in patients who have intraventricular thrombus not susceptible to therapeutic anticoagulation.

Conclusion

This case illustrates that, with the use of cerebral embolic protection, TAVR might still be feasible in inoperable patients who have a persistent LV thrombus and critical aortic stenosis. Devices specifically designed for this purpose play an important clinical role.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Peeyush M. Grover, MD, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine/Jackson Memorial Hospital, Central Bldg., Rm. 600D, 1611 NW 12th Ave., Miami, FL 33136

E-mail: pgrover2@med.miami.edu

References

- 1.Svensson LG, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Roselli EE, Stewart A, Williams M, et al. United States feasibility study of transcatheter insertion of a stented aortic valve by the left ventricular apex. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86(1):46–55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Walther T, Simon P, Dewey T, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Falk V, Kasimir MT, et al. Transapical minimally invasive aortic valve implantation: multicenter experience. Circulation 2007; 116(11 Suppl):I240–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jahangiri M, Laborde JC, Roy D, Williams F, Abdulkareem N, Brecker S. Outcome of patients with aortic stenosis referred to a multidisciplinary meeting for transcatheter valve. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91(2):411–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kahlert P, Knipp SC, Schlamann M, Thielmann M, Al-Rashid F, Weber M, et al. Silent and apparent cerebral ischemia after percutaneous transfemoral aortic valve implantation: a diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation 2010;121(7):870–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Fairbairn TA, Mather AN, Bijsterveld P, Worthy G, Currie S, Goddard AJ, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI determined cerebral embolic infarction following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: assessment of predictive risk factors and the relationship to subsequent health status. Heart 2012;98(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sila CA. Cardioembolic stroke. In: Noseworthy JH, editor. Neurological therapeutics principles and practice. London: Taylor & Francis; 2003. p. 450–7.

- 7.Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Al-Attar N, Antunes M, Bax J, Cormier B, et al. Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). EuroIntervention 2008;4(2):193–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363(17):1597–607. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Safety and efficacy study of the Medtronic CoreValve system in the treatment of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in high risk and very high risk subjects who need aortic valve replacement. Available from: http://inclinicaltrials.com/severe-aortic-stenosis/01240902.aspx [cited 2012 Apr 2].

- 10.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. NIH stroke scale [Internet]. Available from: http://stroke.nih.gov/resources/scale.htm [cited 2012 Jan 30].

- 11.Carpenter JP, Carpenter JT, Tellez A, Webb JG, Yi GH, Granada JF. A percutaneous aortic device for cerebral embolic protection during cardiovascular intervention. J Vasc Surg 2011;54(1):174–181.e1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.McKenzie J, Hattori S, inventors. Implantable cerebral protection device and methods of use. United States patent US 6499487. 2002 Dec 31. Available from: http://www.patents.com/us-6499487.html [cited 2013 Jul 17].