Abstract

Phosphorylation of histone H4 serine 47 (H4S47ph) is catalyzed by Pak2, a member of the p21-activated serine/threonine protein kinase (Pak) family and regulates the deposition of histone variant H3.3. However, the phosphatase(s) involved in the regulation of H4S47ph levels was unknown. Here, we show that three phosphatases (PP1α, PP1β and Wip1) regulate H4S47ph levels and H3.3 deposition. Depletion of each of the three phosphatases results in increased H4S47ph levels. Moreover, PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 bind H3-H4 in vitro and in vivo, whereas only PP1α and PP1β, but not Wip1, interact with Pak2 in vivo. These results suggest that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 regulate the levels of H4S47ph through directly acting on H4S47ph, with PP1α and PP1β also likely regulating the activity of Pak2. Finally, depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 leads to increased H3.3 occupancy at candidate genes tested, elevated H3.3 deposition and enhanced association of H3.3 with its chaperones HIRA and Daxx. These results reveal a novel role of three phosphatases in chromatin dynamics in mammalian cells.

INTRODUCTION

Chromatin, an organized complex of DNA, RNA and proteins, encodes epigenetic information and maintains genome integrity. The basic repeating unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which consists of 147 bp of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer comprising one histone (H3-H4)2 tetramer and two histone H2A-H2B dimers. In addition to canonical histones, histone variants also play an important role in marking chromatin into distinct functional domains and regulating diverse cellular processes including chromosome segregation and gene expression (1–3).

In mammalian cells, there are two major histone H3 variants, CenH3 (CENPA) and H3.3. Compared with canonical histone H3.1 [H3.1 and H3.2, differing by only one amino acid (4–6), we refer H3.1 as the canonical H3 throughout the text for simplicity of discussion], CenH3 and H3.3, while adopting a similar structural fold as H3.1, have distinct functions. For instance, CenH3 is specifically localized at centromere and is important for the establishment and maintenance of a functional kinetochore (1). H3.3, although differing from H3.1 by only five amino acid residues, has unique functions that cannot be substituted by H3.1 (6–8). Early studies indicated that H3.3 was enriched at gene bodies of actively transcribed genes, and the levels of H3.3 at gene bodies positively correlated to gene expression (9–11). Recently, H3.3 has also been found at the promoters of both active and inactive genes in HeLa and embryonic stem cells (12,13). In addition, H3.3 has been detected at pericentric heterochromatin (14,15). Thus, H3.3 likely impacts both active chromatin and heterochromatin. Supporting this idea, the levels of H3.3 have been found to play an important role in maintenance of epigenetic memory of actively transcribed states during nuclear transfer, and mutations at H3.3 compromise formation of heterochromatin during mouse development (15). More recently, it has been shown that H3FA3, one of two genes that encode H3.3, is frequently mutated in pediatric high grade brain tumors and H3.3 mutations are proposed to drive tumor formation (16,17). Thus, it is likely that H3.3 has diverse functions, and alterations of which will lead to human diseases.

The diverse functions of H3.3 are likely related to how H3.3 is deposited onto DNA to form nucleosomes. HIRA, which forms a complex with two other subunits, Cabin and UBN1, is an H3.3-H4 chaperone and aids in the assembly of H3.3-H4 into nucleosomes in a replication-independent manner (18,19). Recently, several groups have reported that the Death domain containing protein (Daxx), which forms a complex with the chromatin remodeling protein ATRX, is another H3.3 chaperone (13,20,21). H3.3 localization at genic regions depends on HIRA, whereas the H3.3 localization at telomeres depends on ATRX in mouse embryonic stem cells (13). Thus, different H3.3 chaperones likely regulate the deposition and localization of H3.3 at distinct genomic regions.

Mutational studies indicate that the three H3.3 specific residues play an important role in specifying H3.3 deposition (9,13). Indeed, the structure of H3.3-H4 and Daxx reveals that two H3.3 unique residues (Ala 87 and glycine 90) are important for the recognition of H3.3 by Daxx (22,23). In addition to these H3 residues, the structure of Daxx-H3.3-H4 complex reveals that Daxx makes extensive contact with histone H4. Similarly, Asf1 also interacts with both H3 and H4 as revealed by the structure of Asf1-H3-H4 complex (24). These findings indicate that histone H4 also mediate the interaction between H3.3-H4 and their chaperones, raising the possibility that modifications on histone H4 can impact the interactions between histone and H3-H4 binding proteins. Indeed, acetylation of H4K5, K12 by Hat1 in human cells enhances the interactions of importin 4 with H3.1, but not H3.3 (25). In addition, phosphorylation of histone H4S47 increases the interaction between H3.3-H4 and HIRA and consequently regulates H3.3 deposition (26). These results indicate that the levels of H4S47ph must be regulated to impact H3.3 deposition in cells.

H4S47 phosphorylation is catalyzed by Pak2, a member of the p21-activated serine/threonine protein kinase (Pak) family that consists of Pak1-Pak6 (27,28). Pak family members participate in a variety of cellular processes and have also been implicated in several cancers (28–30). However, the phosphatases that are involved in regulation of H4S47ph levels were not known. Here, we show that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 are three phosphatases that regulate H4S47ph levels in cells. Depletion of each of the three phosphatases results in increased H4S47ph levels, and each of the three phosphatases interacts with H3-H4 in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, we show that PP1α and PP1β, but not Wip-1, interact with Pak2 in vivo and depletion of PP1α and PP1β affects Pak2 phosphorylation. These results indicate that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 likely regulate H4S47ph levels via different mechanisms. Finally, we show that depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 results in increased H3.3 occupancy at candidate genes tested and enhanced association of H3.3-H4 with HIRA. Together, these results reveal a novel role of PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 in chromatin dynamics in mammalian cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfection and infection

HeLa and OVCAR5 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HCT116 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Stable cell-lines (including those expressing e-H3.1, e-H3.3, each tagged with both the Flag and HA epitopes) were grown in the presence of 1 µg/ml Puromycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. Transient transfection was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lenti-virus based on shRNA was packaged using 293T cells and infected into targeting cells following a procedures as described.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay and real-time PCR

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as described (26). Briefly, for each ChIP assay, 2 × 106 Cells were cross-linked with 1% (v/v) formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and quenched by addition of glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM. Cells were washed with 1× Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)) and then resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 1% TritonX-100, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors]. The cell lysis was sonicated in a Bioruptor (Diagenode) to achieve a mean DNA fragment size of 0.5–1 kb base pairs. After clarification by centrifugation, the supernatants were incubated with 20 µl of anti-Flag agarose (M2 beads, Sigma) overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed extensively, and DNA–protein complex cross-link was reversed by boiling for 10 min in the presence of 10% chelex. The proteins were digested by Proteinase K at 55°C for 30 min. The beads were then centrifuged, and the supernatants containing DNA were collected. The immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed using a real-time PCR machine with iQTM SYBRgreen PCR mastermix (Bio-Rad).

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

The 293T cells were lysed using the lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and proteinase and phosphatases inhibitors (1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Benzamindine, 0.1 mM NaVO3, 10 mM NaF). After clarification by centrifugation, the lysates were incubated with 25 µl of M2 (anti-Flag) beads at 4°C for overnight. The beads were washed using washing buffer [50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% NP40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA and proteinase inhibitors) for 5 min × four times. Proteins were dissolved in 1 × SDS sample buffer [50 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol and 0.005% bromophenol blue] and then loaded onto SDS–PAGE gel. The gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Biorad). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 5% (w/v) skimmed milk powder and then were probed with primary antibodies against HIRA (Millipore), Flag (Sigma), p60 (Abcam), Daxx (Millipore), Asf1a as indicated. For the Flag-H3.1/H3.3 immunoprecipitation with depletion of the phosphatases, 293T cells were lysed using the lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.4), 200 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and proteinase and phosphatases inhibitors 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Benzamindine, 0.1 mM NaVO3, 10 mM NaF] and denounced by 30 passages. After clarification by centrifugation, the lysates were incubated with 30 µl of M2 (anti-Flag) beads at 4°C for overnight. The beads were washed using washing buffer [50 mM HEPES–KOH (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% NP40, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA and proteinase inhibitors] for 5 min × six times. Then, the Flag-H3.1/H3.3 and the co-purified proteins were eluted with 2 mg/ml Flag peptide. The eluted proteins were precipitated using TCA and dissolved with 1 × SDS sample buffer and detected by western blot.

Histone H3.3-SNAP labeling

The SNAP staining was performed as described previously (31). Briefly, 10 µM SNAP block reagent was added to the medium at 37°C for 30 min to quench the SNAP activity. Then, cells were washed with medium three times and incubated in the medium for another 30 min. After chasing for 8 h, 2 µM TMR was added to the medium for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were then pre-extracted with Triton-X100 and fixed in paraformaldehyde. A fluorescence microscope (100×) was used to record the SNAP staining and Image J was used to quantify the SNAP fluorescence intensity. For each experiment, >200 cells were counted. For the chromatin fraction assay, after the SNAP staining, the cells were collected by trypsin and washed with PBS. Cells were extracted with CSK buffer on ice for 5 min followed by high speed centrifugation. The chromatin pellet was washed with PBS again and boiled in 1 × SDS sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and SANP-tagged proteins were detected by Typhoon 7900, and the total proteins were visualized by IRDye® Blue Protein Stain and used for loading controls.

RESULTS

Phosphatases PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 regulate the levels of H4S47 phosphorylation

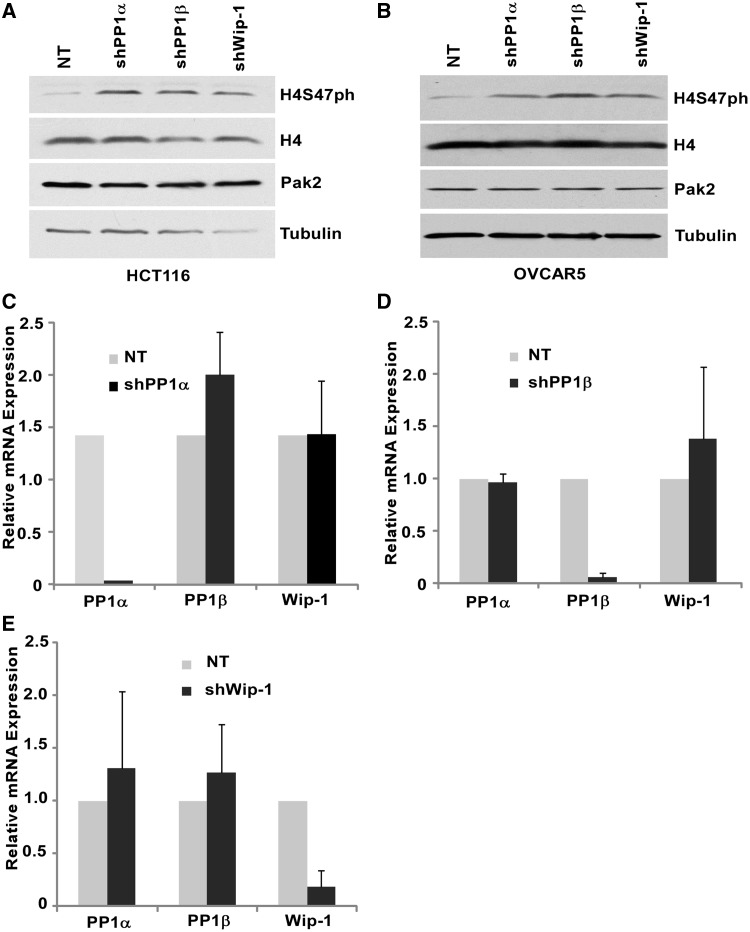

We have shown previously that Pak2 is the primary kinase that phosphorylates H4S47 in mammalian cells (26). To identify a phosphatase(s) responsible for the regulation of H4S47ph level, we purchased all available shRNAs targeting seven different catalytic subunits of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases from Sigma and tested how depletion of each affected H4S47 levels in HeLa cells. We found that cells treated with at least two shRNAs targeting PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 resulted in increased H4S47 phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure S1). To confirm this result, PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 were depleted from two other cell lines, HCT116 and OVCAR5. In both cell lines, depletion of each of the three phosphatases resulted in a dramatic increase in H4S47ph (Figure 1A and B). In addition, depletion of PP1α did not affect the expression of PP1β or Wip-1 (Figure 1C). Similar results were observed for depletion of PP1β and Wip1 (Figure 1D and E). Together, these results suggest that PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 likely regulate H4S47ph independently.

Figure 1.

Depletion of phosphatases PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 result in increased H4S47ph levels in OVCAR5 and HCT116 cells. (A and B) Depletion of phosphatases PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 led to a dramatic increase in H4S47ph levels in HCT116 (A) and OVCAR5 (B). HCT116 or OVCAR5 cells were infected with shRNA containing viruses targeting PP1α, PP1β, Wip-1 or non-target (NT) virus as a control. Whole-cell protein extract were prepared 72 h post-infection, and western blots were performed using antibodies against H4S47ph, H4 and Tubulin or Pak2. C-E, PP1α (C), PP1β (D) or Wip-1 (E) is efficiently and specifically depleted by its own shRNA in OVCAR5 cells. Total RNA was prepared 72 h post-infection, and real-time RT-PCR was performed to examine the expression level of each phosphatase.

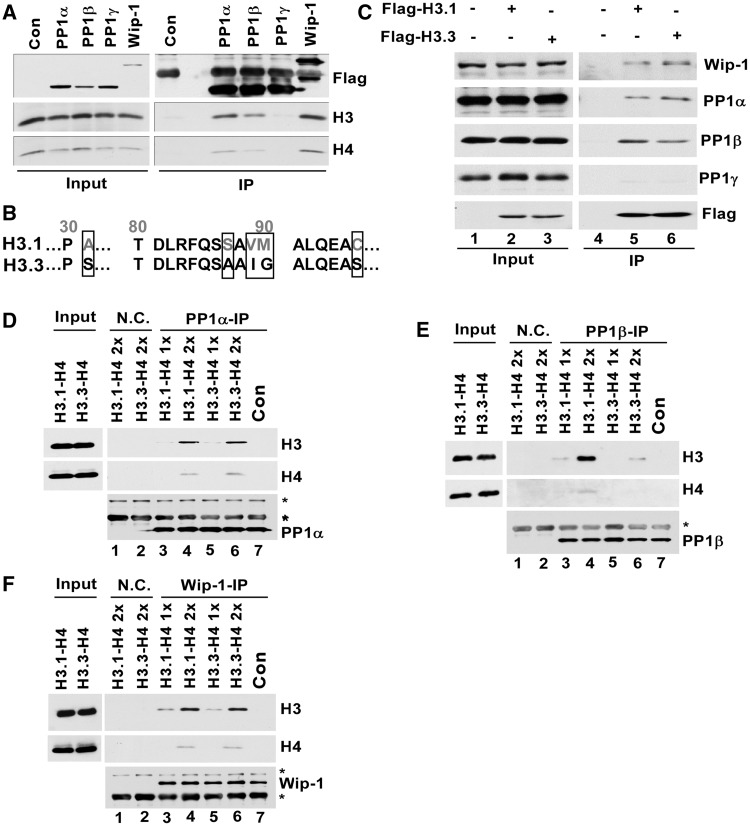

PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interact with H3-H4 in vivo and in vitro

PP1α and PP1β are two members of PP1 family Ser/Thr phosphatases including PP1γ. Wip-1 is a member of PP2C family phosphatases (32,33). To understand how depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1 affects the levels of H4S47 phosphorylation, we first determined whether each phosphatase interacted with H3-H4. Transiently expressed and Flag-tagged PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ or Wip-1 was immunoprecipitated from 293T cells, and co-precipitated proteins were analyzed by western blot. H3 and H4 were detected in the precipitates of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1, but not those of PP1γ (Figure 2A). Canonical histone H3.1 and histone H3 variant H3.3 differ by 5 amino acids (Figure 2B). In a reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments, we tested whether each phosphatase co-purified with H3.1 and H3.3. PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1, but not PP1γ, were co-purified with histone e-H3.1 or e-H3.3 (Figure 2C). These results are consistent with idea that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1, but not PP1γ, are H4S47ph phosphatases. To test this idea further, we asked whether each phosphatase purified from 293T cells interacted with recombinant H3.1-H4 or H3.3-H4 tetramers in vitro. As shown in Figure 2D–F, PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interacted with H3.1-H4 or H3.3-H4 in vitro. In addition, although PP1α and Wip-1 bound similar amounts of H3.1-H4 and H3.3-H4, we consistently observed that PP1β bound more H3.1-H4 than H3.3-H4 in vitro and in vivo (compare lanes 5–6 in Figure 2C and lanes 3–4 to lanes 5–6 in Figure 2E). These results demonstrate that phosphatases PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interact with H3-H4 complex in vivo and in vitro and suggest that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 may regulate the levels of H4S47ph by directly removing H4S47 phosphorylation.

Figure 2.

PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interact with H3-H4 in vivo and in vitro. (A) H3 and H4 were co-immunoprecipitated with PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 in vivo. The 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid-expressing Flag tagged PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ or Wip-1. PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ or Wip-1 was immuno-precipitated with M2 beads. As a negative control (Con), the same purification procedures were performed using non-transfected 293T cells. Proteins in whole-cell extract (Input) and Immunoprecipitation (IP) were analyzed by western blot using antibodies against Flag, H3 or H4. (B) Comparison of the protein sequence of H3.1 and H3.3. (C) PP1α, PP1β, and Wip-1 were co-immunoprecipitated with H3.1 and H3.3. The 293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag-tagged H3.1 or H3.3 and H3.1 or H3.3 were purified, and the co-purified proteins were analyzed using antibodies against PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ and Wip-1. (D-F) PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interacted with H3-H4 complex in vitro. PP1α (D), PP1β (E) and Wip-1 (F) were purified from 293T cells and then mixed with two different amounts of recombinant H3.1-H4 or H3.3-H4. Each phosphatase was immunoprecipitated, and the co-precipitated proteins were detected by western blot. The band marked by asterisk is likely to be IgG heavy chain or a non-specific band.

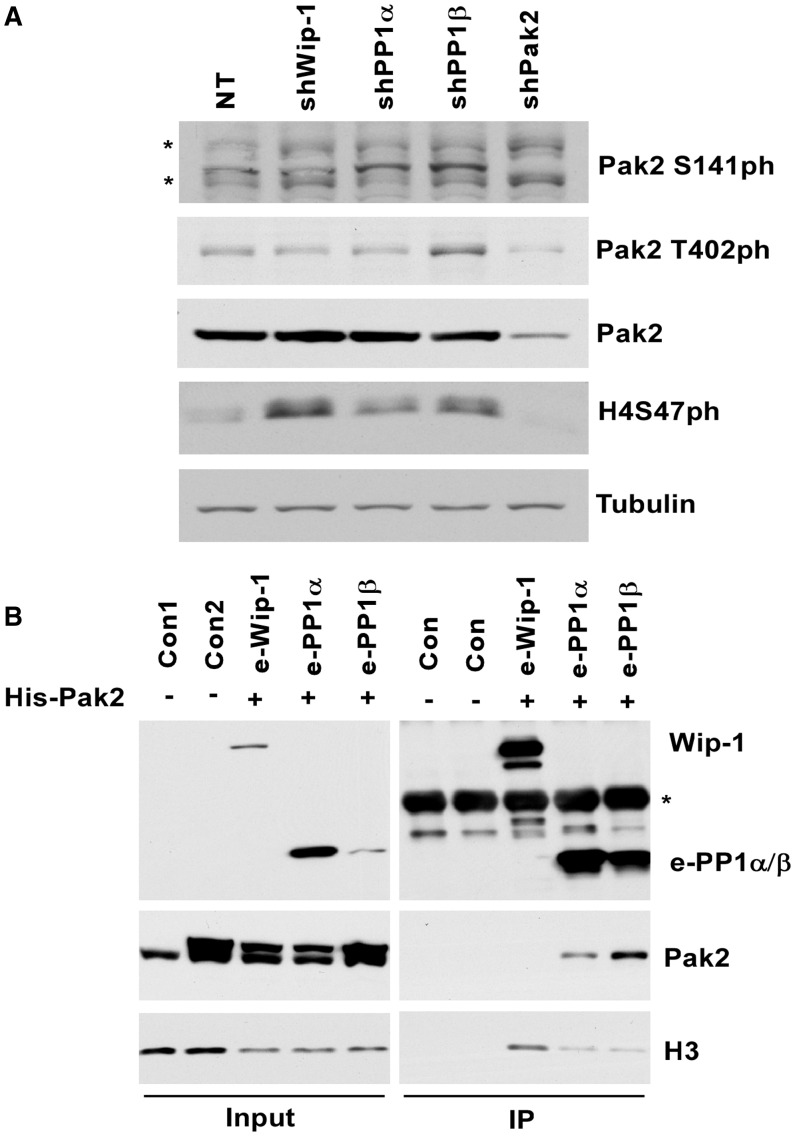

PP1α and PP1β regulate Pak2 phosphorylation

The H4S47 kinase, Pak2, contains an auto-inhibitory domain at its N-terminus that binds the catalytic domain and inhibits catalytic activity of Pak2 (27). Therefore, Pak2 must be activated to phosphorylate its substrates including H4S47. It is known that phosphorylation of Pak2 T402 at the activation loop and/or S141 at the auto-inhibitory domain results in Pak2 activation. Therefore, there exists the possibility that Wip1, PP1α or PP1β regulates H4S47ph levels by dephosphorylating these residues. To test this possibility, we also determined how depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 affected phosphorylation of Pak2 T402 or S141. Depletion of both PP1α and PP1β resulted in increased Pak2 phosphorylation at serine 141. In addition, PP1β depletion also resulted in increased Pak2 phosphorylation T402, whereas Wip-1 depletion did not affect phosphorylation of either residue of Pak2 (Figure 3A). These results suggest that PP1α and PP1β likely also regulate H4S47ph levels through impacting the activation of Pak2 kinase. Consistent with this idea, we observed that PP1α and PP1β, but not Wip1 interact with Pak2 in vivo (Figure 3B). Together, these results indicate that PP1α and PP1β likely also regulate the levels of H4S47ph indirectly through regulating the activity of Pak2 kinase.

Figure 3.

PP1α and PP1β regulate Pak2 phosphorylation. (A) Depletion of PP1α and PP1β led to increased Pak2 phosphorylation. OVCAR5 cells were infected with viruses targeting PP1α, PP1β, Wip-1, Pak2 or non-target (NT) control. Proteins in whole-cell extracts were detected by western blots using indicated antibodies. (B) PP1α and PP1β interacted with Pak2 in vivo. A plasmid for expressing his-tagged Pak2 was co-transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag tagged PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 into 293T cells. Flag-tagged PP1α, PP1β, PP1γ and Wip-1 were purified. As negative controls, the same purification procedures were followed using normal 293T (Con1) and 293T cells expressing only His-Pak2 (Con2). Western blots were performed using indicated antibodies to analyze the proteins in whole-cell extract (Input) and immuno-precipitation (IP).

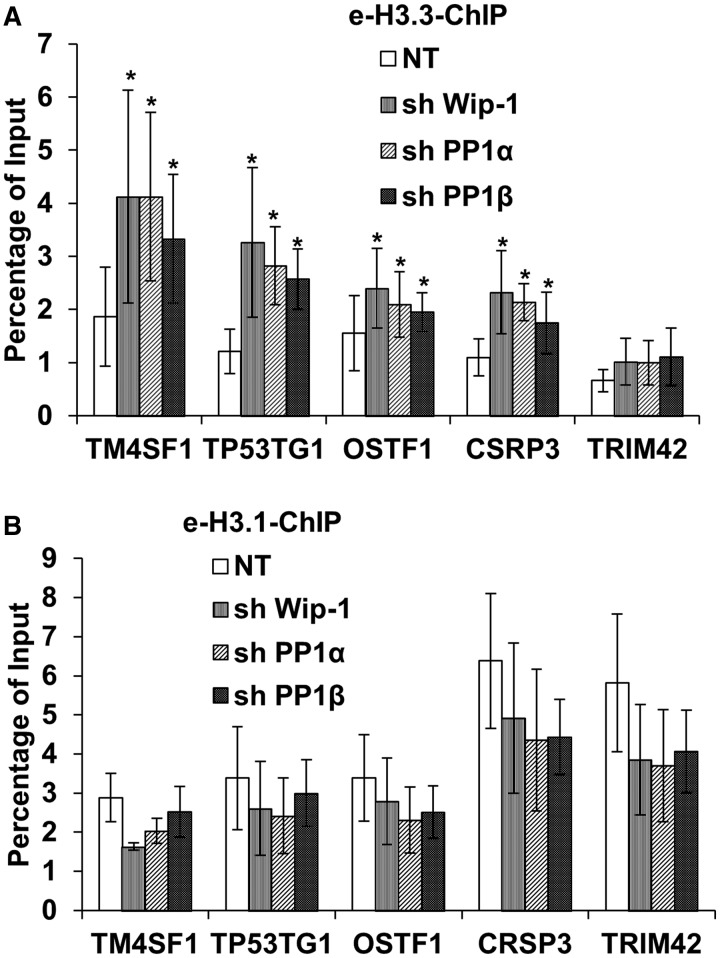

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 affects H3.3 occupancy

We have shown previously that depletion of Pak2 reduces the H3.3 occupancy (26). Therefore, we tested whether depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 has any effect on H3.3 occupancy using a ChIP assay. As reported previously, e-H3.3 was enriched at the genome regions flanking the transcription start site (TSS) of TP53TG1, OSTF1 and the transcription terminal site (TTS) of TM4SF1, whereas e-H3.1 is enriched in the regions flanking TSS of TRIM42 and TTS of CSRP1 (Figure 4). Importantly, depletion of phosphatases PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 led to a significant increase in the H3.3 occupancy at three H3.3-enriched genes (TMSF1, TP53TG1 and OSTF1) tested. Interestingly, depletion of each of the phosphatases also led to the increased H3.3 occupancy at CSRP3, but not TRIM42, even though both are H3.1-enriched genes (Figure 4A). These results are consistent with the idea that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 regulate H4S47ph levels, which in turn promotes H3.3 deposition.

Figure 4.

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 results in increased occupancy of H3.3 in three H3.3-enriched genes. HeLa cells expressing e-H3.3 (A) or e-H3.1 (B) tagged with the Flag and HA epitopes were infected with viruses for shRNA PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1. Cells were collected for ChIP assays using antibodies against the Flag epitope 72 h after infection. NT: non-targeting control. ChIP DNA and input DNA were analyzed by real-time PCR using primers annealing to three H3.3 enriched genes (TSS of TP53TG1 and OSTF1 and the TTS of TM4SF1) and two H3.1 enriched genes (the TSS and TTS of TRIM42 and CSRP3, respectively). The average and standard derivations from at least three independent experiments were shown. Student’s t-test was performed, and samples with a P < 0.05 were marked as asterisk.

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 did not impact the H3.1 occupancy at the two H3.1 candidate genes tested significantly (Figure 4B). As depletion of Pak2 results in increased e-H3.1 occupancy at these candidate genes (26), one would expect that depletion of H4S47ph phosphatase will have the opposite effect on e-H3.1 occupancy as that of Pak2 depletion. One possible explanation for the apparent discrepancy is that the effect of depleting PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 on H3.1 occupancy is marginal owing to the presence of two other H4S47ph phosphatases in cells. Nonetheless, our results indicate that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 can regulate H3.3 occupancy at these candidate genes, revealing a novel function of these phosphatases in chromatin dynamics.

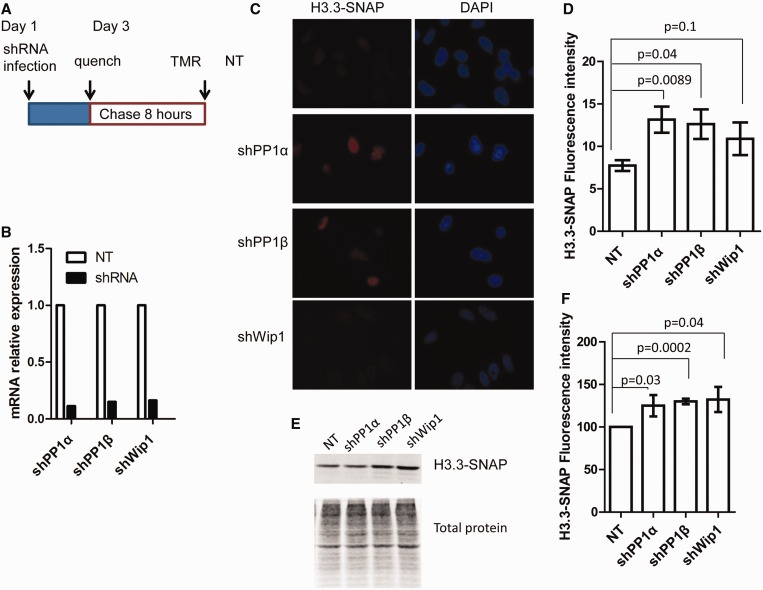

Deposition of newly synthesized H3.3 increases in cells with PP1α and PP1β depletion

To understand how depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1 affects H3.3 occupancy at chromatin, we established H3.3-SNAP stable cell line as described (31). A SNAP tag is a mutant form of O6-guanine nucleotide alkyltransferase that covalently reacts with benzyl-guanine. To monitor the deposition of newly synthesized H3.3, we performed the ‘quench-chase’ experiment as outlined in Figure 5A. Briefly, after depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1 (Figure 5B), old H3.3-SNAP reacted with benzyl-guanine derivative and would not give rise to fluorescence. After washing away the blocker for 30 min, newly synthesized H3.3 (after 8 h) was labeled with TMR and detected with fluorescence. As shown in Figure 5C and D, compared with non-targeting controls, depletion of PP1α or PP1β resulted in a significant increase in H3.3 intensity compared with control cells (NT). In addition, using an independent chromatin fraction assay, the effect of depletion of PP1α and PP1β on H3.3 deposition was also observed (Figure 5E and F). Interestingly, although depletion of Wip-1 also resulted in an increase in H3.3 deposition using both fluorescence and chromatin fraction assays, the effect of Wip-1 depletion on H3.3 intensity using the fluorescence-based assay from three independent experiments was not statistically significant (P = 0.1) (Figure 5D), which could be due to the mild increase in H3.3 intensity in Wip-1-depleted cells. Together, these results indicate that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 regulate H3.3 deposition.

Figure 5.

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 result in increased deposition of newly synthesized H3.3. (A) A schematic diagram outlining H3.3-SNAP labeling procedure. HeLa cells stably expressing H3.3-SNAP were infected with viruses targeting PP1α, PP1β or Wip-1. H3.3-SNAP was blocked with SNAP blocking reagent 72 h after infection. Eight-hour after removal of the blocking reagent, cells were either fixed for detection of newly synthesized H3.3-SNAP, which reacted with TMR, using a fluorescence microscopy (C–D) or extracted for preparation of chromatin as described in experimental procedures to detect new H3.3-SNAP using SDS–PAGE analysis (E-F). (B) PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 were efficiently knockdown as examined by real-time RT-PCR. The experiment was performed as described in Figure 1C. (C and D), Depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 results in increased H3.3 fluorescence intensity. (C) The representative images. (D) The average and standard deviation of fluorescence intensity from three independent experiments. Image J was used to quantify fluorescence intensity of at least 200 cells from each experiment. (E and F) Deposition of new H3.3 was monitored by a chromatin fractionation assay. Chromatin fractions were prepared and new H3.3-SNAP was detected using a Typhoon FLA 7000, and total proteins were detected by IRDye® Blue Protein Stain. The relative SNAP intensity over total protein was reported as the average and standard deviation of three independent experiments. P-values were shown in D and F.

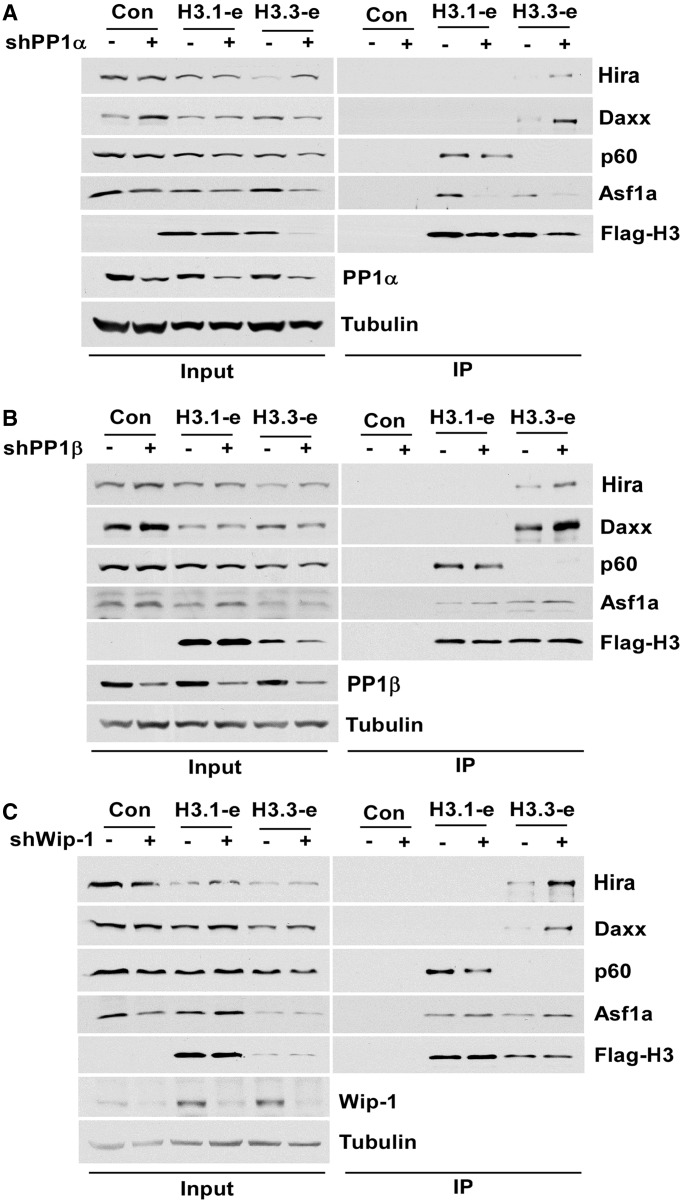

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 results in increased interaction between H3.3-H4 and its chaperones, Daxx and HIRA

To understand how PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 impact deposition of H3.3, we performed in vivo immunoprecipitation to determine whether depletion of each phosphatase affects the association of H3.3-H4 with its chaperons, HIRA and Daxx. As shown in Figure 6, depletion of phosphatases PP1α, β and Wip-1 resulted in increased association of H3.3 with HIRA and Daxx, two H3.3 chaperones. However, we did not observe consistent changes in the association of H3.3 with other histone chaperones including Asf1a after depletion of each phosphatase. Furthermore, we did not observe consistent changes in the association of H3.1 with H3.1 chaperones CAF-1 or Asf1a and Asf1b (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 affect H3.3 occupancy through their impact on the association of H3.3-H4 with H3.3 chaperones.

Figure 6.

Depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 impact the interaction of H3.3 with its chaperone HIRA and Daxx. The 293T cells stably expressing e-H3.1 or e-H3.3 tagged with both Flag and HA epitope were infected with viruses for non-target or shRNA against PP1α (A), PP1β (B) and Wip-1 (C) phosphatase. Seventy-two hours after infection, e-H3.1 or e-H3.3 was purified using M2 beads and eluted with Flag peptide. e-H3.1, e-H3.3 and the co-purified proteins were precipitated using TCA. As a control (Con), mock purifications were performed following the similar procedures using cells without expression of e-H3.1 or e-H3.3. Western blots were performed using antibodies against indicated proteins.

DISCUSSION

H4S47ph is catalyzed by the Pak2 kinase. Here, we have presented the following lines of evidence supporting the idea that three phosphatases, PP1α, PP1β and Wip1, regulate the level of H4S47ph. First, we show that depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1, but not the catalytic subunits of four other phosphatases, results in increased H4S47ph levels in three different cell lines tested. Second, we show that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 interact with H3-H4 in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 are directly involved in removing H4S47ph. Third, we show that PP1α and PP1β, but not Wip1, interact with Pak2, and depletion of PP1α and PP1β, but not Wip-1, results in increased phosphorylation of Pak2T402 and S141. Phosphorylation of these two residues is known to be involved in Pak2 activation (27). Therefore, the observed increase in H4S47ph levels in PP1α and PP1β depleted cells is also likely due, in part, to the activation of Pak2 in these cells. These results indicate that PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 regulate H4S47ph levels by acting as the H4S47ph phosphatases, with PP1α and PP1β also regulating the Pak2 kinase activity.

Although depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1 results in increased levels of H4S47ph, depletion of each does not affect the expression of the other two phosphatases. These results suggest that PP1α, PP1β and Wip1 regulate H4S47ph levels independently. PP1α and PP1β are the catalytic subunits of the PP1 phosphatase family phosphatases that consist of three distinct catalytic subunits, PP1α, PP1β and PP1γ. PP1 family phosphatases dephosphorylate many cellular proteins and achieve substrate specificity through PIPs (protein phosphatase interacting proteins). These PIPs helps bridge the PP1 to a specific substrate (32). Therefore, it is possible that PP1α and PP1β use different PIPs to interact with H3-H4 or Pak2, which in turn regulates the H4S47ph levels. Consistent with this idea, we consistently observe that PP1β binds more H3.1 than H3.3. Therefore, it is possible that PP1β is the phosphatase that dephosphorylates serine 47 on H4 in the H3.1-H4 complex. Wip-1 belongs to PP2C family of serine/threonine phosphatase whose activity is dependent on Mn2+/Mg2+. The substrate recognition domain of Wip1 in general resides at the regulator domain of Wip-1. In the future, it would be interesting to determine how PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 recognize H3-H4 and/or Pak2, which in turn regulate the levels of H4S47ph.

Using three independent different assays, we show that depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip-1 results in increased H3.3 deposition and occupancy. First, the H3.3 occupancy at H3.3-enriched genes as detected by ChIP assay increases after depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1. Second, deposition of new H3.3 as measured by fluorescence intensity of H3.3-SNAP increases after depletion of PP1α, PP1β and Wip1. Finally, chromatin bound new H3.3-SNAP as detected by the chromatin fractionation assay increases in cells with depletion of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1. These results demonstrate a novel role of PP1α, PP1β or Wip1 in regulating H3.3 deposition/exchange.

Wip-1 plays an important role in DNA damage response by dephosphorylating activated ATM and Chk2 kinases (34). Wip-1 is also likely involved in aging process. For instance, the expression of Wip-1 is reduced during the aging process, and this reduction leads to increased expression of p16INK4a (a cell cycle inhibitor and a senescence marker in aging cells), through activation of p38MAKP kinase, which phosphorylates BMI1 (a component of PRC1 complex represses transcription of p16INK4a) and initiates the release of BMI1 from chromatin (35). In addition, overexpression of Wip-1 compromises RAS-induced senescence (36) in fibroblast cells. It is known that histone chaperone Asf1a and H3.3 chaperone HIRA are required for oncogenic RAS-induced senescence, possibly through their role in mediating H3.3 deposition (37). Because Wip-1 depletion results in increased H3.3 deposition, we suggest that the role of Wip-1 in RAS-induced senescence and/or in aging cells is at least partially due to its ability to regulate H3.3 deposition described here. Future studies are needed to test this idea.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

NIH [GM81838, CA157489 and P50 CA136393]. Zhiguo Zhang is a Scholar of Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. Funding for open access charge: Mayo Clinic and Epigenomics Programme, Center of Individualized medicine.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Genevieve Almouzni for her advice on establishment of H3.3-SNAP technology before publication of her studies. They also thank Drs Almouzni and Ray-Gallet for their critical comments on the manuscript. They thank Dr Sherry L. Winter and Dr Irene L. Andrulis from University of Toronto for kindly providing PP1α, PP1β and PP1γ expressing plasmids. They also appreciate Dr Albert J. Fornace from Georgetown University for giving us the Wip-1 expressing plasmid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Talbert PB, Henikoff S. Histone variants – ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;11:264–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess RJ, Zhang Z. Histone chaperones in nucleosome assembly and human disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:14–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ransom M, Dennehey B, Tyler JK. Chaperoning histones during repair and replication. Cell. 2010;140:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elsaesser SJ, Goldberg AD, Allis CD. New functions for an old variant: no substitute for histone H3.3. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2010;20:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szenker E, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G. The double face of the histone variant H3.3. Cell Res. 2011;21:421–434. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szenker E, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G. The double face of the histone variant H3.3. Cell Res. 2011;21:421–434. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakai A, Schwartz BE, Goldstein S, Ahmad K. Transcriptional and developmental functions of the H3.3 histone variant in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1816–1820. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couldrey C, Carlton MB, Nolan PM, Colledge WH, Evans MJ. A retroviral gene trap insertion into the histone 3.3A gene causes partial neonatal lethality, stunted growth, neuromuscular deficits and male sub-fertility in transgenic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:2489–2495. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad K, Henikoff S. The histone variant H3.3 marks active chromatin by replication-independent nucleosome assembly. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz BE, Ahmad K. Transcriptional activation triggers deposition and removal of the histone variant H3.3. Genes Dev. 2005;19:804–814. doi: 10.1101/gad.1259805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mito Y, Henikoff JG, Henikoff S. Genome-scale profiling of histone H3.3 replacement patterns. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1090–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin C, Zang C, Wei G, Cui K, Peng W, Zhao K, Felsenfeld G. H3.3/H2A.Z double variant-containing nucleosomes mark ‘nucleosome-free regions' of active promoters and other regulatory regions. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:941–945. doi: 10.1038/ng.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg AD, Banaszynski LA, Noh KM, Lewis PW, Elsaesser SJ, Stadler S, Dewell S, Law M, Guo X, Li X, et al. Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions. Cell. 2010;140:678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hake SB, Garcia BA, Kauer M, Baker SP, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Allis CD. Serine 31 phosphorylation of histone variant H3.3 is specific to regions bordering centromeres in metaphase chromosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6344–6349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502413102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santenard A, Ziegler-Birling C, Koch M, Tora L, Bannister AJ, Torres-Padilla ME. Heterochromatin formation in the mouse embryo requires critical residues of the histone variant H3.3. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010;12:853–862. doi: 10.1038/ncb2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, Qu C, Ding L, Huether R, Parker M, et al. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:251–253. doi: 10.1038/ng.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, Khuong-Quang DA, Jones DT, Konermann C, Pfaff E, Tonjes M, Sill M, Bender S, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray-Gallet D, Quivy JP, Scamps C, Martini EM, Lipinski M, Almouzni G. HIRA is critical for a nucleosome assembly pathway independent of DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00526-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tagami H, Ray-Gallet D, Almouzni G, Nakatani Y. Histone H3.1 and H3.3 complexes mediate nucleosome assembly pathways dependent or independent of DNA synthesis. Cell. 2004;116:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campos EI, Reinberg D. New chaps in the histone chaperone arena. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1334–1338. doi: 10.1101/gad.1946810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drane P, Ouararhni K, Depaux A, Shuaib M, Hamiche A. The death-associated protein DAXX is a novel histone chaperone involved in the replication-independent deposition of H3.3. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1253–1265. doi: 10.1101/gad.566910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsasser SJ, Huang H, Lewis PW, Chin JW, Allis CD, Patel DJ. DAXX envelops a histone H3.3-H4 dimer for H3.3-specific recognition. Nature. 2012;491:560–565. doi: 10.1038/nature11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu CP, Xiong C, Wang M, Yu Z, Yang N, Chen P, Zhang Z, Li G, Xu RM. Structure of the variant histone H3.3-H4 heterodimer in complex with its chaperone DAXX. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:1287–1292. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English CM, Adkins MW, Carson JJ, Churchill ME, Tyler JK. Structural basis for the histone chaperone activity of Asf1. Cell. 2006;127:495–508. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Han J, Kang B, Burgess R, Zhang Z. Human histone acetyltransferase 1 protein preferentially acetylates H4 histone molecules in H3.1-H4 over H3.3-H4. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:6573–6581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang B, Pu M, Hu G, Wen W, Dong Z, Zhao K, Stillman B, Zhang Z. Phosphorylation of H4 Ser 47 promotes HIRA-mediated nucleosome assembly. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1359–1364. doi: 10.1101/gad.2055511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bokoch GM. Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:743–781. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sells MA, Chernoff J. Emerging from the Pak: the p21-activated protein kinase family. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:162–167. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar R, Vadlamudi RK. Emerging functions of p21-activated kinases in human cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002;193:133–144. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siu MK, Wong ES, Chan HY, Kong DS, Woo NW, Tam KF, Ngan HY, Chan QK, Chan DC, Chan KY, et al. Differential expression and phosphorylation of Pak1 and Pak2 in ovarian cancer: effects on prognosis and cell invasion. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;127:21–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray-Gallet D, Woolfe A, Vassias I, Pellentz C, Lacoste N, Puri A, Schultz DC, Pchelintsev NA, Adams PD, Jansen LE, et al. Dynamics of histone H3 deposition in vivo reveal a nucleosome gap-filling mechanism for H3.3 to maintain chromatin integrity. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:928–941. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell. 2009;139:468–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bollen M, Peti W, Ragusa MJ, Beullens M. The extended PP1 toolkit: designed to create specificity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliva-Trastoy M, Berthonaud V, Chevalier A, Ducrot C, Marsolier-Kergoat MC, Mann C, Leteurtre F. The Wip1 phosphatase (PPM1D) antagonizes activation of the Chk2 tumour suppressor kinase. Oncogene. 2007;26:1449–1458. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Guezennec X, Bulavin DV. WIP1 phosphatase at the crossroads of cancer and aging. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009;35:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Kim J, Ruthazer R, McDevitt MA, Wazer DE, Paulson KE, Yee AS. The HBP1 transcriptional repressor participates in RAS-induced premature senescence. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8252–8266. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00604-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang R, Poustovoitov MV, Ye X, Santos HA, Chen W, Daganzo SM, Erzberger JP, Serebriiskii IG, Canutescu AA, Dunbrack RL, et al. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.