Abstract

Background

Subjective social status (SSS), an individual’s subjective view of standing in society, has been shown to better predict health outcomes compared to objective measures of socioeconomic status (SES), including educational attainment and income. This study examines the relationship between SSS and severity of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use after controlling for objective measures of SES.

Methods

Young adults (N = 1987) aged 18–25 who reported smoking at least one cigarette in the past 30 days were recruited and surveyed anonymously online. Three separate structural equation models examined whether SSS was associated with severity of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use, controlling for personal and household income, years of education, employment status, and parental education.

Results

Household income (b = .31), employment status (b = .07), years of education (b = .09), and parental education (b = .16) were positively associated with SSS (all p-values < .001); personal income was not significantly associated with SSS (p = .11). All three models adequately fit the data. SSS was negatively associated with severity of tobacco (b = −.13, p < .001) and marijuana use (b = −36, p = .02), but not alcohol use severity (b =.01, p = .56).

Conclusions

Among young adults, higher subjective social status is associated with less severe tobacco and marijuana use, whereas alcohol use severity appears to be similar across socioeconomic class.

Keywords: Subjective social status, Socioeconomic status, Smokers, Substance use, Young

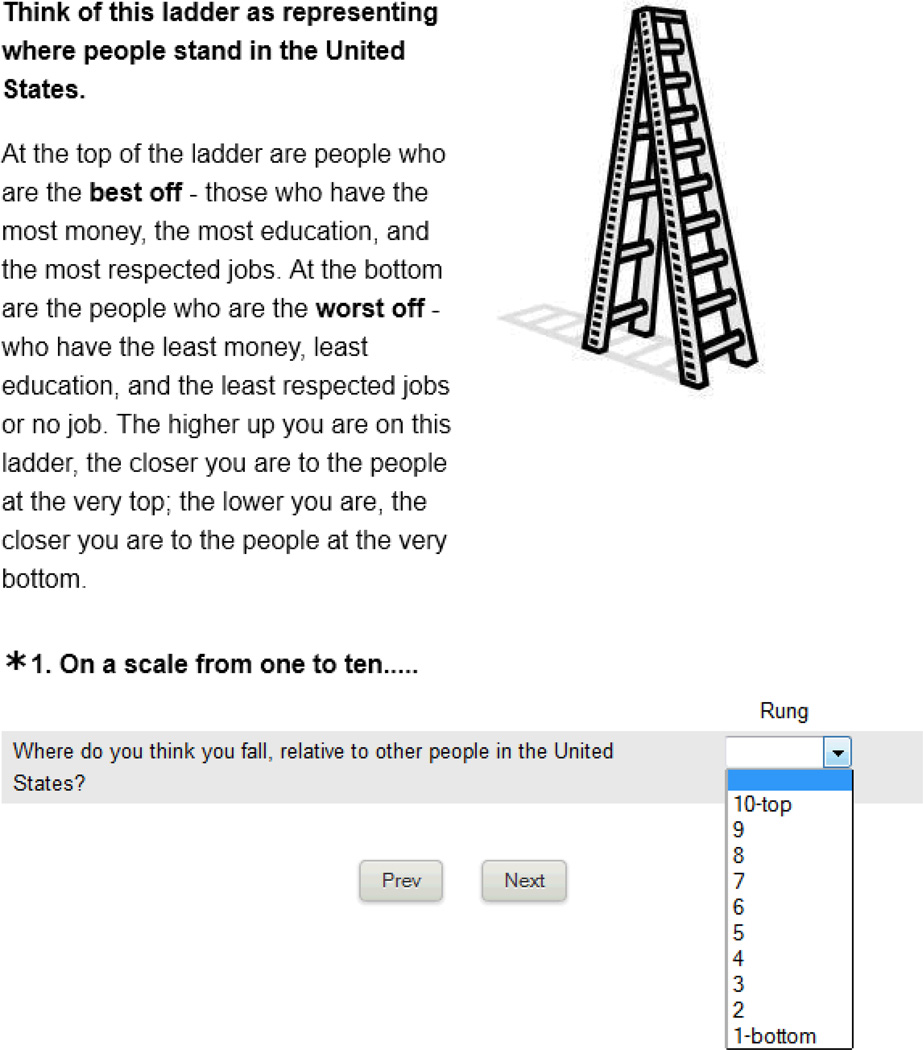

Social determinants, such as socioeconomic status (SES), have received a great deal of study due to their impact on health (Marmot, 2005; Stringhini et al., 2010). Going beyond traditional measures of SES, such as income or education, there is growing interest in subjective social status (SSS), a measure of an individuals' sense of social standing relative to others in the United States. It includes an individual’s subjective appraisal of his or her current socioeconomic standing and potential for future improvement in status in comparison to others (Adler, 2000). Thus, while a traditional occupation status measure would not distinguish an individual working in a job characterized by having little or no income potential, long hours, and low pay from another individual employed in an environment with opportunities for income growth and expansion of social ranking, SSS would likely differ greatly for these individuals based on perceptions of future prospects and opportunities. SSS has been measured with a schematic scale using a 10-rung ladder numbered 1 to 10 that has individuals indicate the rung on which they feel they stand relative to others in the Unites States with regard to money, education and jobs (Figure 1). Previous research investigating the determinants of SSS has found that both economic and social considerations are relevant in rankings. Thus, one’s assignment of SSS is not solely based on the factors the measure explicitly asks about in the instructions (e.g., money; Singh-Manoux, Adler, & Marmot, 2003).

Figure 1.

MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status. Details available from: http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php

Relative to traditional SES indicators of educational level, personal income, and total household income, SSS is a better predictor of health status and decline in health status over time in middle-aged adults (Singh-Manoux, Marmot, & Adler, 2005). SSS is related to a range of health indicators, including self-rated health, mortality, depression, cardiovascular risk, diabetes, and respiratory illness (Singh-Manoux et al., 2003). In adolescent populations, SSS is associated with depression, obesity (Goodman et al., 2001), and poor self-rated health (Goodman, Huang, Schafer-Kalkhoff, & Adler, 2007).

Low SES is related to unhealthy behaviors (Lynch, Kaplan, & Salonen, 1997; Redonnet, Chollet, Fombonne, Bowes, & Melchior, 2011), and has been posited as an explanation for disparities in health outcomes (Stringhini et al., 2010). While tobacco use has been consistently associated with low SES, prior studies have found alcohol and marijuana use to be related to both low SES and affluence (Lynch et al., 1997; Patrick, Wightman, Schoeni, & Schulenberg, 2012; Redonnet et al., 2011; Richter, Vereecken, Boyce, Gabhainn, & Currie, 2009). The assessment of SSS may be a useful construct in clarifying inconsistencies noted in the relationship between substance use and economic position. In a longitudinal study with adolescents, lower SSS in one’s school community predicted smoking initiation (Finkelstein, Kubzansky, & Goodman, 2006). SSS, however, has not been examined in relation to young adult smoking intensity or patterns of alcohol and marijuana use.

This study builds on the literature by examining associations between SSS and young adults’ severity of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use. The transition to adulthood is becoming increasingly longer in industrialized countries, and better characterizing young adults’ perceptions of social position and substance use may provide key insights into a growing population that is in a dynamic state of change (Arnett, 2005). We hypothesized that after statistically controlling for traditional indicators of SES (household income, parental education, years of education, and employment status), higher SSS would be associated with lower severity of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use.

Methods

Procedures

This U.S.-based cross-sectional survey recruited English literate young adults aged 18–25 who reported smoking at least one cigarette in the past month. Procedures have been described in detail previously [References removed for blind review]. Briefly, young adults were recruited online between 4/1/09 and 12/31/10 to take a 20-minute online survey with a chance to win one of twenty seven $25 gift cards or one of six $400 gift cards. Survey website included an IRB-approved consent form, a screener for additional eligibility criteria, followed by the survey. Participants had to answer all questions before continuing on, but could quit the survey at any time. Eligibility checks excluded respondents who had discrepant data from duplicate demographic questions indicating they were not between ages 18–25 (n = 112). Cases were excluded from analyses if respondents reported the same email address across multiple survey entries (n = 12), if data were clearly invalid (n = 10), or if the reported recruitment method differed from verifiable recruitment statistics (n = 6).

Participants

The online survey received at least 7567 hits; 7260 people gave online consent to determine eligibility for study completion, of which 3748 (52%) were eligible and deemed valid cases. Of these, 3578 (95.5%) completed at least demographic measures, and 1987 (53.0%) completed the entire survey. Compared to completers (n = 1987), those who did not complete the survey (n = 1591) were significantly younger (age M = 20.2 vs. 20.6; t = 6.60, p < .001), had fewer years of education (M = 12.8 years vs. 13.2 years; t = 4.29, p < .001), more likely to be male (69% vs. 63%; χ2 = 20.32, p < .001); Caucasian (73% vs. 71%; χ2 = 14.01, p = .02), and had more education (92% HS degree vs. 90% high school degree; χ2 = 35.75, p < .001). Although statistically significant, these differences were of small magnitude and likely related more to the large sample size than to meaningful group differences. Nonetheless, the sample may have been biased with respect to some sociodemographic characteristics.

Measures

Measures and procedures used in this study were previously analyzed for reliability and validity via anonymous online sampling with young adults and demonstrated to be appropriate [References removed for blind review]. Demographic variables included race/ethnicity, years of education, parental education, employment status, personal, and household incomes (including the participant and anyone whose income they share [e.g., parents, partner]). Baseline SSS was measured with the U.S. version of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (Adler, 2000; Figure 1).

Timeline Followback (TLFB) procedures (Brown et al., 1998) assessed number of days smoked in the past 30 and average number of cigarettes per day. Smoking-related information assessed in this online survey demonstrated high correlations with other smoking measures (internal-consistency reliability), smoking constructs (construct validity) and sociodemographic characteristics (Ramo, Hall, & Prochaska, 2011), and estimates of smoking quantity were comparable to those from nationally representative household interviews. One item from the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence assessed time to first cigarette in the morning (5 minutes, 6–30 minutes, 31–60 minutes, or after 60 minutes). This item correlates highly with the full test (Payne, Smith, McCracken, McSherry, & Antony, 1994) and is the single best indicator of dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, Rickert, & Robinson, 1989).

Alcohol use was measured with the TLFB scored to yield (1) number of days drinking in the past 30 days, (2) average drinks per drinking day, and (3) number of heavy drinking days (Sobell, Sobell, Leo, & Cancilla, 1988). Heavy drinking days were defined as 5 or more drinks for men and 4 or more drinks for women.

The TLFB also measured number of days using marijuana in the past 30 days (Sobell & Sobell, 1996). Age at first use of marijuana was collected, as per the 2007 NSDUH (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008). Cannabis dependence symptoms were assessed with the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test (CUDIT; Adamson & Sellman, 2003) and replaced in March 2010 with the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R; Adamson et al., 2010) due to improved psychometric properties of the newer measure. 77.2% of the final sample completed the revised measure. Scores on the CUDIT and CUDIT-R were converted to z-scores and pooled for analyses.

Analyses

Analyses of variance and correlations were used to examine differences in SSS between demographic variables and measures of objective social status. For three objective measures of social status (individual income, household income, and parental education) linear contrasts were used to test for a trend by category.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine whether SSS was associated with a latent construct of substance use controlling for objective measures of SES using MPlus 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Model fit was assessed for each substance independently through a two-step procedure (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). First, a measurement model was fit for each substance latent variable (tobacco, alcohol, marijuana) and their three observable indicators with all paths left free to vary. Then, a hypothesized structural path model was fit wherein household income, parental education, personal income, years of education, employment status, and SSS were regressed upon the latent substance use variable. Weighted least squares means variance (WLSMV) estimation was used in the tobacco model to account for the categorical nature of one latent variable indicator (i.e., time to first cigarette). Alcohol and marijuana models used robust maximum likelihood estimation (ML). Both methods incorporate missing data procedures to maximize use of available data. Model fit for the tobacco use model (using WLSMV) was indexed using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), weighted root mean square residual (WRMR; Muthèn & Muthèn, 1998–2006) and model chi-square. Model fit for the alcohol and marijuana models using ML used the CFI, RMSEA, model chi-square, and standardized root mean risidual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for sociodemographic variables and substance use. Tobacco use occurred on about two-thirds (M = 22 days, SD = 11.4) of days in the past month and mean cigarettes per day was 7 (SD = 6.9). Almost half (43.9%) of participants reported their first cigarette within at least one hour after waking. Use of alcohol and marijuana were not study inclusion criteria; yet, the majority of participants had consumed alcohol at least once in the past month (79%). On average, drinking occurred approximately 6 days per month (SD = 7.5), averaging 5 drinks per drinking occasion (M = 4.8, SD = 3.4). Participants 21 years and older drank more often than younger participants (M = 7.3 vs. 5.2 days; t = 6.26, p < .001). Men drank more often than women (M = 6.8 vs. 5.0 days; t = 5.17, p < .001). Slightly more than half of participants used marijuana in the past month (54%), and use averaged 9 days in the past month. Relationships between SSS and demographic characteristics, objective measures of socioeconomic status

Table 1.

Descriptives, subjective social status (SSS) by demographic and substance use characteristics, and tests of differences in SSS by demographics (N = 1987)

| Variable | Sample Characteristics |

Mean SSS value |

Pearson’s r or F* |

p- value |

Linear quadratic term |

p-value for linear term |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age–M (SD) | 20.61 (2.10) | −.05 | .017 | -- | -- | |

| Gender-% | 4.20a | .041 | -- | -- | ||

| Female | 36.7 | 5.12 (1.76) | ||||

| Male | 62.8 | 5.29 (1.95) | ||||

| Transgender | 0.5 | 4.67 (1.41) | ||||

| Ethnicity-% | 1.24 | .286 | -- | -- | ||

| African-American | 3.1 | 5.18 (1.88) | ||||

| Asian-American/Pacific Islander | 4.0 | 5.38 (1.81) | ||||

| Caucasian-American | 71.2 | 5.26 (1.90) | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.3 | 5.13 (1.85) | ||||

| Multi-Ethnic | 9.9 | 5.23 (1.79) | ||||

| Other | 5.5 | 4.83 (1.90) | ||||

| Years of education–M (SD) | 13.16 (2.19) | .16 | .000 | -- | -- | |

| Employment/education status-% | 37.03 | .000 | -- | -- | ||

| Employed (>= 20 hours/week) | 30.0 | 5.20 (1.76) | ||||

| Employed part-time (<20 hours/week) | 15.8 | 5.17 (1.73) | ||||

| Unemployed/retired/homemaker | 25.5 | 4.64 (2.06) | ||||

| Student | 28.7 | 5.81 (1.75) | ||||

| Parents’ highest education-% | 19.73 | .000 | 5.85 | .016 | ||

| No formal education | 0.3 | 4.50 (1.52) | ||||

| Some grade school | 0.4 | 4.00 (1.41) | ||||

| Completed grade school | 0.6 | 4.73 (1.79) | ||||

| Some high school or less | 2.4 | 4.77 (1.93) | ||||

| Completed high school/GED | 17.3 | 4.48 (1.76) | ||||

| Some college | 16.0 | 4.94 (1.88) | ||||

| Complete college | 33.3 | 5.31 (1.81) | ||||

| Some graduate work | 2.0 | 4.77 (1.84) | ||||

| A graduate degree | 25.6 | 5.94 (1.81) | ||||

| Don’t know | 2.3 | 4.93 (2.00) | ||||

| Personal Income-% | 1.52 | .179 | 3.53 | .060 | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 85.3 | 5.19 (1.91) | ||||

| $21,000 – $40,000 | 11.1 | 5.30 (1.62) | ||||

| $41,000 – $60,000 | 2.2 | 5.57 (1.73) | ||||

| $61,000 – $80,000 | 0.8 | 5.81 (1.52) | ||||

| $81,000 – $100,000 | 0.2 | 6.00 (2.94) | ||||

| Over $100,000 | 0.5 | 6.33 (2.78) | ||||

| Household Income-% | 55.16 | .000 | 308.24 | .000 | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 27.1 | 4.68 (1.95) | ||||

| $21,000 – $40,000 | 21.2 | 4.64 (1.73) | ||||

| $41,000 – $60,000 | 15.2 | 5.08 (1.64) | ||||

| $61,000 – $80,000 | 10.6 | 5.34 (1.51) | ||||

| $81,000 – $100,000 | 8.6 | 5.93 (1.74) | ||||

| $100,000 – $200,00 | 11.7 | 6.23 (1.66) | ||||

| Over $200,000 | 5.6 | 7.08 (1.64) | ||||

| Days smoked, past 30–M (SD) | 22.64 (11.35) | −.13 | .000 | -- | -- | |

| Cigarettes per day–M (SD) | 7.41 (6.86) | −.13 | .000 | -- | -- | |

| Time to first cigarette-% | 18.12 | .000 | -- | -- | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 13.5 | 4.69 (2.08) | ||||

| 6 – 30 minutes | 22.9 | 4.94 (1.75) | ||||

| 31 – 60 minutes | 19.6 | 5.29 (1.80) | ||||

| After 60 minutes | 43.9 | 5.51 (1.87) | ||||

| Drank alcohol in past 30 days-% | 78.5 | 5.28 (1.85) | 5.21 | .023 | -- | -- |

| Days drinking, past 30–M (SD) | 6.15 (7.52) | .05 | .019 | -- | -- | |

| Drinks per drinking day–M (SD) | 4.84 (3.36) | −.01 | .839 | -- | -- | |

| Heavy drinking days–M (SD) | 2.87 (4.66) | .02 | .409 | -- | -- | |

| Used marijuana, past 30 days-% | 53.5 | 5.26 (1.93) | .87 | .350 | -- | -- |

| Days using marijuana, past 30–M (SD) | 8.98 (11.97) | −.02 | .458 | -- | -- | |

| Age at first marijuana use–M (SD) | 15.33 (2.41) | .11 | .000 | -- | -- | |

| Total | 5.23 (1.88) |

Correlations or ANOVA tests examined relationships between SSS and demographic or substance use characteristics.

Nine transgendered participants were not included in gender difference analyses due to small n.

There was a small but significant negative association between age and SSS (r = −.05, p = .02), and men had a slightly higher SSS than women (Table 1). There were no differences in SSS by ethnicity.

Higher individual education was associated with higher SSS (r = .16, p < .001; Table 1). SSS differed by employment status, such that full-time students had the highest SSS, followed by those employed full or part-time; SSS was lowest among the unemployed (F = 37.03, p < .001). SSS increased significantly with higher parental education (linear quadratic term = 5.85, p = .02) and household income (linear quadratic term = 308.24, p < .001). Higher personal income was not significantly associated with higher SSS (linear quadratic term = 3.53, p = .060).

Correlational analyses

Bivariate correlations for the main study variables are presented in Table 2. There were strong correlations among household income, parental education, SSS, and tobacco use variables and strong correlations among indicators of alcohol and marijuana use. Several of the correlations, although significant, were weak (r < .10).

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for objective measures of socio-economic status, subjective social status, and substance use variables (N = 1987)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Years of education | — | −.03 | .13** | .13** | .21** | .18** | −.06** | −.08** | −.17** | .09** | −.10** | .04 | .01 | −.07* | .18** |

| 2. Employment status | — | −.34** | .07** | .06** | .11** | −.09** | −.14** | −.09** | −.01 | .04 | .01 | .03 | .03 | −.04 | |

| 3. Personal income | — | .14** | −.01 | .04 | .06** | .09** | .06* | .06** | −.04 | .02 | −.06** | −.04 | .03 | ||

| 4. Household income | — | .25** | .35** | −.08** | −.07** | −.14** | .12** | .06* | .12** | .08** | .03 | .03 | |||

| 5. Parents’ education | — | .27** | −.10** | −.11** | −.15** | .15** | .01 | .12** | .11** | .03 | .11** | ||||

| 6. Subjective social status | — | −.13** | −.14** | −17** | .08** | .01 | .06** | .01 | .01 | .11** | |||||

| 7. Days smoked, past 30 days | — | .66** | .44** | .16** | .02 | .14** | .13** | .03 | −.12** | ||||||

| 8. Cigarettes smoked per day | — | .59** | .09** | .11** | .11** | .08** | .06* | −.17** | |||||||

| 9. Time to first cigarette | — | −.11** | .03 | −.07** | −.01 | .06* | −.18** | ||||||||

| 10. Days using alcohol, past 30 days | — | .06* | .72** | .20** | .09** | −.03 | |||||||||

| 11. Drinks per drinking day | — | .44** | .03 | .06* | −.08** | ||||||||||

| 12. Heavy drinking days, past 30 | — | .15** | .08** | −.08** | |||||||||||

| 13. Days using marijuana, past 30 | — | .39* | −.20** | ||||||||||||

| 14. CUDIT total scorea | — | −.15** | |||||||||||||

| 15. Age first MJ use | — |

Note. CUDIT = Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test; MJ = marijuana. Spearman’s rho correlations used for personal income, household income, employment status, parent’s education, subjective social status, time to first cigarette. All other correlations are Pearson’s r.

CUDIT scores are z-scores of CUDIT and CUDIT-R.

p < .05.

p <. 01.

Relationships between SES, SSS, and Substance use

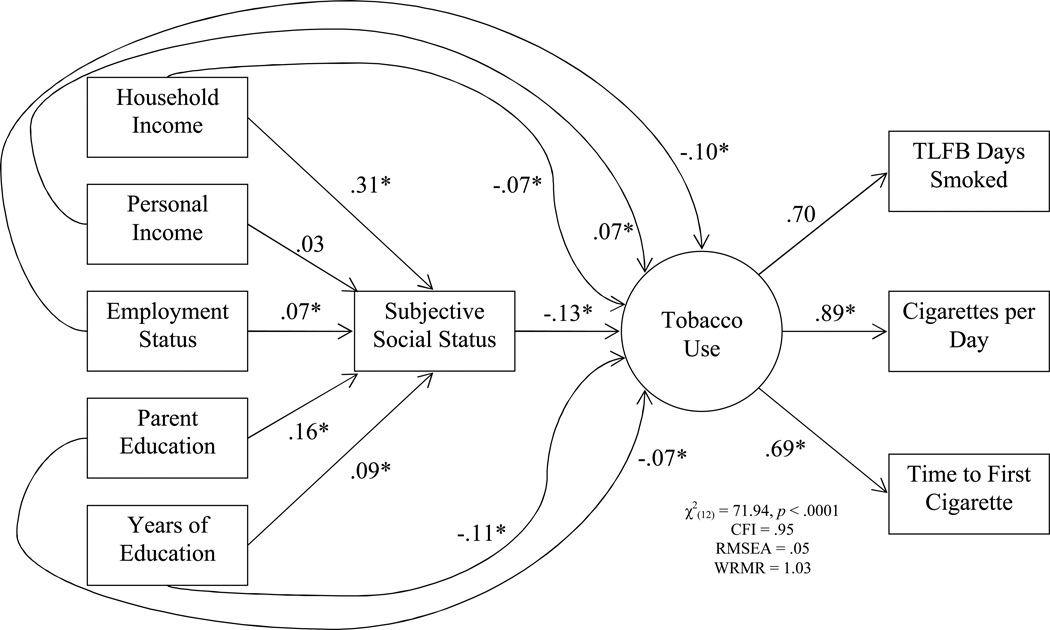

The structural equation model testing the relationship between SSS and tobacco use, controlling for SES indictors is presented in Figure 2. Alcohol and marijuana models differ only by the latent variable and its three indicators. In all three models, SSS was significantly positively associated with household income (r = .31, p < .0001), parental education (r = .16, p < .0001), years of education (r = .09, p < .0001), and employment status (r = .07, p = .002), but not personal income (r = .03, p < .11). We consider each model below.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model for tobacco use: Subjective social status predicting tobacco use (latent variable), controlling for household income, personal income, employment status, parental education, and years of education. Standardized coefficients presented. * p < .05.

The tobacco measurement model included one latent variable measuring tobacco use intensity. Standardized estimates were all high and significant (days using tobacco: b = .70 p < .0001; average cigarettes per day: b = .95, p < .0001; time to first cigarette: b = .63, p < .0001). The structural model indicated good model fit (χ2 = 71.94, p < .0001; CFI = .95; RMSEA = .05; WRMR = 1.03; see Table 2 for correlations). SSS significantly predicted tobacco use controlling for the five objective measures of SES (b = −.13, p < .001), which also were associated with tobacco use (Figure 2).

The alcohol measurement model included one latent variable measuring alcohol use intensity. Standardized estimates were all large and significant (days using alcohol: b = .78, p < .0001; average drinks per drinking days: b = .99, p < .0001; heavy drinking days: b = .91, p < .0001). The overall model indicated good model fit (χ2 = 49.67, p < .001; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .01; see Table 2 for correlations). In this model, SSS was not significant. Household income (b = .05, p = .037) and parental education were predictive of alcohol use (b = .05, p = .033), while personal income (b = .04, p = .13), employment status (b = .02, p = .43), years of education (b = .02, p = .29), and SSS (b = −.01, p = .56) were not.

In the marijuana measurement model, standardized estimates were all significant for the latent measure of marijuana intensity (days using marijuana: b = .70, p < .001; marijuana dependence symptoms: b = .54, p < .001; age of first marijuana use: b = −.28, p < .001). The overall model indicated good fit (χ2 = 99.26, p < .0001; CFI = .88; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .04; Table 2 for correlations). Lower SSS (b = −.08, p = .02) was associated with higher marijuana use intensity, as was higher household income (b = .08, p = .02) and greater parental education (b = .10, p = .002). Years of education (b = −.05, p = .14), employment status (b = .01, p = .82), and personal income (b = −.06, p = .06) were not associated with marijuana use.

Discussion

This study offers preliminary evidence that, both traditional SES and SSS are differentially related to young adult smokers’ use of substances. For tobacco, lower SSS was associated with more severe tobacco use among young adult smokers above the risk that low SES already poses for smoking. This could be explained in part by stress in that social disadvantage is associated with increased stress among adolescents, and higher baseline stress and lower SSS in adolescence is associated with higher likelihood of smoking (Finkelstein et al., 2006; Goodman, McEwen, Dolan, Schafer-Kalkhoff, & Adler, 2005). Tobacco use may serve as a maladaptive coping strategy for managing adverse life circumstances including low SSS and associated stress. Additionally, the movement to de-normalize smoking and promote the social unacceptability of smoking behavior has had profound effects on tobacco use in the U.S. (Alamar & Glantz, 2006).

In contrast to findings with tobacco, objective measures of SES were weakly but significantly positively associated with alcohol and marijuana use, which may reflect the contribution of increased disposable income to consumption of these substances (Redonnet et al., 2011). Yet, as with tobacco, lower SSS was associated with greater marijuana use, suggesting that those with lower SSS may experience environmental, cognitive, and/or emotional, risk factors for the use of marijuana as young adults. Further research is needed to characterize these mediators and understand whether they differ from those for tobacco use, especially given trends toward increased marijuana use with decreased perceived harm among young people (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011). Young adults with low SSS may employ marijuana use as a means of coping with stress and adverse life circumstances. Since the relationship between SSS and marijuana use was only significant when participants were equated on objective measures of SES, it suggests the relationship is stronger for those comparable on SES and highlights the importance of controlling for SES in this type of research.

Alcohol use appears to behave differently than tobacco or marijuana use among young adults in regards to SSS, which could be related to the social acceptability of alcohol. Peer influences are important determinants of alcohol use in adolescents and college students, acting through direct offers to use, modeling, and social norms (Ali & Dwyer, 2010; Borsari & Carey, 2001). This modeling effect was maintained in all social status conditions (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985), a finding which is consistent with the lack of relationship between SSS and drinking behavior in the current study. Among adolescents, individuals are socially rewarded for conforming to their peers’ level of alcohol use (Balsa, Homer, French, & Norton, 2011), suggesting that the use of alcohol in accordance with social norms may reflect adaptive social behavior. Additionally, a study exploring social influences on decision-making in substance use found that implicit, non-conscious attitudes were susceptible to social influences, particularly for alcohol (Coronges, Stacy, & Valente, 2011), further highlighting the complexity underlying one’s decision to use alcohol. Future work should consider SSS related to one’s social standing in their community (community ladder) to explore the extent to which a more proximal reference point influences the relationship between SSS and alcohol use. Future work should also incorporate a measure of alcohol dependence (e.g., Alcohol Dependence Scale, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) into the model of SSS and alcohol use.

This study had some limitations with respect to study design and methodology. The cross-sectional design prohibits inferences of causality between SSS and substance use severity, and data reflect only a specific time point in participants’ developmental trajectory. The sampling method, which targeted only current smokers, limits generalizability to nonsmokers. Selection bias is further impacted by the fact that non-English speakers and those without Internet access were excluded. The study sample may have been biased with respect to some sociodemographic characteristics, as there were differences between completers and non-completers that were of small magnitude, though statistically significant. Additionally, key information regarding sources of income and whether or not participants were living with parents prevented knowing whether incomes truly reflected poverty status. Though the self-report methodology used has specific advantages, reliance on participants’ self-report of substance use and individual and parental socioeconomic parameters may be problematic. Additionally, we did not collect data regarding parental substance use, which may serve as modeling of behavior for offspring, or participants’ mental health, which may be another mediator of SSS and substance use.

This study was also limited by challenges in accurately assessing social standing in a young adult population. SES is inherently difficult to capture among young adults as they may be in a dynamic process of change related to education and finances. We opted to use five measures of objective SES in the present study, incorporating both personal and household/parental indicators. Nonetheless, our measures may lack the ability to make direct comparisons to studies with more robust measures of SES (e.g., percent of poverty index, U.S. census). Accurately assessing SSS in the emerging adult population may pose similar challenges. Emerging adulthood is increasingly being understood as a distinct developmental stage, characterized by prevalent substance use and a general sense of optimism despite adverse circumstances, factors that may have affected the present study’s findings (Arnett, 2000). In regards to the SSS measure, the present study utilized only the SSS measure asking individuals to rank themselves relative to other people in the U.S. Given the complexity of social networks and peer influences that underlie substance use in adolescents and young adults, the SSS version ranking relative to a self-defined community may have produced different results. Finally, although the SEM models demonstrate good fit with the data, we cannot exclude the possibility that alternative models may have been an equivalent or better fit. Model replication within multiple samples is important for establishing the validity of findings.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that while tobacco and marijuana use are similarly affected by SSS, alcohol has a unique pattern of associations with SSS. Findings underscore the usefulness of the ladder measure of SSS, as it maximizes information with minimal respondent burden. SSS was significantly associated with individual education level and current status as a full-time student, but not with current individual income, suggesting that the measure is capturing an appraisal of future prospects. By appraising both economic and social factors, the SSS measure likely captures an individual’s standing more fully than traditional SES indicators and may be a reasonable alternative for measuring socioeconomic position. Further study of this unique construct may clarify the nuances involved in assessing social standing in emerging adults. The present study makes preliminary connections between SSS and substance use; future research using this novel construct may focus on mediating factors that could account for differential relationships between SSS and substance use among young adults, and to understand how findings impact treatment efforts with this population.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by an institutional training grant (T32 DA007250; PI, J. Sorensen), a center grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; P50 DA09253; PI, J. Guydish), and an individual Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the California Tobacco-Related Diseases Research Program (18FT-0055; PI, D. Ramo). Manuscript preparation was supported in part by a mentored career development award from the NIDA (K23 DA032578, D. Ramo, P.I.), a research project grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH083684, J. Prochaska, P.I.), and a research award from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (#13-KT-0152). The authors wish to thank Nancy Adler for her comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

List of abbreviations

- SSS

Subjective social status

- SES

Socio-economic status

Footnotes

None of the authors has a conflict of interest related to this study.

Contributor Information

Karen A. Finch, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco..

Danielle E. Ramo, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco..

Kevin L. Delucchi, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco.

Howard Liu, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco..

Judith J. Prochaska, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Department of Medicine, Stanford University, and Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, Sellman JD. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(1–2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson SJ, Sellman JD. A prototype screening instrument for cannabis use disorder: the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in an alcohol-dependent clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2003;22(3):309–315. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE. MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status [Measure] San Francisco, CA: MacArthur Research Network on Socioeconomic Status and Health; 2000. Retrieved from http://www.macses.ucsf.edu/research/psychosocial/subjective.php. [Google Scholar]

- Alamar B, Glantz S. Effect of increased social unacceptability of cigarette smoking on reduction in cigarette consumption. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1359–1363. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MM, Dwyer DS. Social network effects in alcohol consumption among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step program. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, Homer JF, French MT, Norton EC. Alcohol use and popularity: Social payoffs from conforming to peers' behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(3):559–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2001;13(4):391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2):101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, LJ S, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Parks G, Marlatt G. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronges K, Stacy AW, Valente TW. Social network influences of alcohol and marijuana cognitive associations. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1305–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein DM, Kubzansky LD, Goodman E. Social status, stress, and adolescent smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(5):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Adler NE, Kawachi I, Frazier AL, Huang B, Colditz GA. Adolescents' perceptions of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E31. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Huang B, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler NE. Perceived socioeconomic status: A new type of identity that influences adolescents' self-rated health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41(5):479–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, McEwen BS, Dolan LM, Schafer-Kalkhoff T, Adler NE. Social disadvantage and adolescent stress. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(6):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.11.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: Using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(7):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings,2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT. Why do poor people behave poorly? Variation in adult health behaviours and psychosocial characteristics by stages of the socioeconomic lifecourse. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44(6):809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. MPlus 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Muthèn LK, Muthèn B. MPlus User’s Guide. 2nd Edition ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthèn & Muthèn; 1998–2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: A comparison across constructs and drugs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(5):772–782. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772. Retrieved from http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne TJ, Smith PO, McCracken LM, McSherry WC, Antony MM. Assessing nicotine dependence: A comparison of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) in a clinical sample. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19(3):307–317. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of self-reported smoking in an anonymous online survey with young adults. Health Psychology. 2011;30(6):693–701. doi: 10.1037/a0023443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redonnet B, Chollet A, Fombonne E, Bowes L, Melchior M. Tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and other illegal drug use among young adults: The socioeconomic context. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;121(3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Vereecken CA, Boyce W, Gabhainn SN, Currie CE. Parental occupation, family affluence and adolescent health behaviour in 28 countries. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54(4):203–212. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-8018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Adler NE, Marmot MG. Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(6):1321–1333. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):855–861. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers' reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83(4):393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, Brunner E, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(12):1159–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2008. DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343. [Google Scholar]