Abstract

Objective

Preclinical and clinical studies have suggested that therapeutic hypothermia, while decreasing neurological injury, may also lead to drug toxicity that may limit its benefit. Cooling decreases cytochrome p450(CYP)-mediated drug metabolism and limited clinical data suggest that drug levels are elevated. Fosphenytoin is metabolized by CYP2C, has a narrow therapeutic range, and is a commonly used antiepileptic medication. The objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of therapeutic hypothermia on phenytoin levels and pharmacokinetics in children with severe TBI.

Design

Pharmacokinetic analysis of subjects participating in a multicenter randomized Phase III study of therapeutic hypothermia for severe TBI.

Setting

Intensive care unit at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh

Patients

Nineteen children with severe TBI.

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

A total of 121 total and 114 free phenytoin levels were evaluated retrospectively in 10 hypothermia- and 9 normothermia-treated children who were randomized to 48h of cooling to 32–33°C followed by slow rewarming or controlled normothermia. Drug dosing, body temperatures, and demographics were collected during cooling, rewarming, and post-treatment periods(8 days). A trend towards elevated free phenytoin levels in the hypothermia group(p=0.051) to a median of 2.2 mg/L during rewarming was observed and was not explained by dosing differences. Nonlinear mixed effects modeling incorporating both free and total levels demonstrated that therapeutic hypothermia specifically decreased the time-variant component of the maximum velocity of phenytoin metabolism(Vmax) 4.6-fold(11.6 to 2.53 mg/h) and reduced the overall Vmax by ~50%. Simulations showed that the increased risk for drug toxicity extends many days beyond the end of the cooling period.

Conclusions

Therapeutic hypothermia significantly reduces phenytoin elimination in children with severe TBI leading to increased drug levels for an extended period of time after cooling. Pharmacokinetic interactions between hypothermia and medications should be considered when caring for children receiving this therapy.

Keywords: children, drug metabolism, hypothermia, phenytoin, pharmacokinetics, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

The clinical use of therapeutic hypothermia, defined as the controlled reduction of body temperature to 32–34°C, is expanding despite incomplete knowledge of its collateral effects on concomitant therapies. Randomized controlled trials(RCTs) documenting improvements in mortality and neurological outcomes following adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (1, 2) and hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy(HIE) (3–6) have generated excitement surrounding the use of hypothermia for neuroprotection. In other cerebral ischemic injuries such as traumatic brain injury(TBI), however, consistent efficacy remains elusive. Clinical trials support the use of hypothermia to control elevated intracranial pressure(ICP), but multicenter RCTs have failed to demonstrate an improvement in mortality or neurological outcome (7–10). Adverse reactions such as increased hypotension requiring vasopressors and decreased cerebral perfusion pressure during the cooling and rewarming phases have been implicated as potential causes for the lack of benefit in these patients (10, 11). Additionally, it is well-known that guidelines-based therapy of TBI in children involves the use of a relatively large number of medications, contrasting treatment of HIE (12). It is unknown whether these hypothermia-related adverse events are directly due to cooling or due to medication-related interactions.

Therapeutic hypothermia is known to decrease cytochrome p450 (CYP) drug metabolism (13, 14), but clinical data remains sparse due to challenges in conducting pharmacokinetic studies in critically ill patients, especially children. Phenytoin and its prodrug fosphenytoin are metabolized by CYP2C9/19 and are commonly-used for seizure prophylaxis following TBI and in other populations receiving therapeutic hypothermia (15, 16). Independent of cooling, dosing is challenging and therapeutic monitoring is routinely performed due to its narrow therapeutic range and nonlinear Michaelis-Menton pharmacokinetics (metabolism does not increase proportionally with dose and is induced by injuries such as TBI) (17–20).

Based on the common use of phenytoin products in several populations treated with therapeutic hypothermia and limited available data, we aimed to determine the impact of therapeutic hypothermia on phenytoin levels and pharmacokinetics in children participating in a multicenter RCT. To achieve this goal, we developed a population pharmacokinetic model that simultaneously described free and total phenytoin concentrations as well as identified the covariates of phenytoin exposure after TBI. We further simulated the phenytoin concentration-time profiles in this population to best understand the risk and timing of phenytoin toxicity in children receiving therapeutic hypothermia to aid clinicians caring for similar patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Children admitted to the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center with severe TBI who were enrolled in a prospective, Phase III RCT of therapeutic hypothermia and who received fosphenytoin or phenytoin were included in this study. The objective of the NIH-funded Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury Consortium: Hypothermia(“Cool Kids Trial”, clinicaltrials.gov:NCT00222742) was to determine the effect of induced, moderate hypothermia on outcomes after severe TBI in children. Inclusion criteria included age <18, a closed head injury, Glasgow Coma Scale(GCS) score <8(motor component <6). Exclusion criteria included the inability to initiate cooling within 6h of injury, a GCS of 3 and abnormal brainstem function, a normal initial CT scan, penetrating brain injury, unknown mechanism/time of injury, uncorrectable coagulopathy(PT/PTT >16/40 sec, INR >1.7), hypotension(systolic blood pressure less than the 5th percentile for age for >10 min), pregnancy, or a hypoxic episode(oxygen saturation <94% for >30 min). TBI management was protocol-driven as reported previously and in accordance with published pediatric guidelines (21, 22). All patients had external ventriculostomy drains and intraparenchymal catheters placed to monitor ICP and intracranial hypertension was treated using a tiered approach of positional maneuvers, continuous cerebrospinal fluid diversion, sedation, neuromuscular blockade, vasoactive medications, osmolar therapies(mannitol and/or hypertonic [3%] saline), and pentobarbital. Decompressive surgery was considered when medical therapies had failed. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained.

Temperature management

Following hemodynamic and pulmonary stabilization, subjects were randomized to receive either controlled normothermia (36.5–37.9°C) or moderate hypothermia (32–33°C) for 48h. A rectal temperature probe was used to measure core body temperature. Target temperature attainment in those randomized to the hypothermia group was achieved using surface cooling (cooling blankets placed below the patient and ice packs placed in the groin and/or the axillae), cold intravenous saline (20–30mL/kg), and occasionally, gastric lavage as needed during cooling induction. Following 48h of cooling, patients were slowly re-warmed at a rate of 1°C per 12–24h until normothermia was attained. If intracranial pressure became elevated during rewarming, this rate was slowed to 1°C every 24–36h.

Drug administration, sampling, and data collection

Fosphenytoin is routinely used as prophylactic anti-seizure therapy in children following severe TBI at our institution. Within 12h of injury, an intravenous loading dose of 10–20mg/kg was administered to each patient and maintenance therapy of 5–7mg/kg divided every 12h was initiated 12h later. Blood samples for fosphenytoin therapeutic drug monitoring were drawn as part of routine clinical care. Dosing was in phenytoin-equivalents and adjusted based on clinical status and serum phenytoin levels in relationship to established therapeutic ranges (unbound/free phenytoin concentration[Cfree], 1–2 mg/L); total phenytoin concentration[Ctotal], 10–20 mg/L) (23). Concentrations were measured at the Children’s Hospital of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center using a particle-enhanced turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay(Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA) with or without initial sample ultrafiltration, respectively. Clinical data collection occurred over 168h and included demographic information, injury severity scores(GCS and Injury Severity Score (ISS)), liver and renal function tests, hourly rectal temperatures, amount and timing of fosphenytoin or phenytoin doses, and any concurrent medications. All study times were measured from time of injury and all data were collected within a database by the University of Pittsburgh Data Coordinating Center.

Demographic data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation(SD) unless the data were not normally distributed, in which case median and range were reported. As an initial crude analysis, the potential effect of cooling on phenytoin Cfree and cumulative drug dosing was explored by comparing group assignment (hypothermia or normothermia) on these measurements across the study periods using a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance with Graphpad Prism 5.04(Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). The analysis of Cfree was limited to the rewarming and post-treatment periods to to focus on changes in drug elimination versus volume of distribution. If individual patients had multiple concentrations drawn within each period, they were first averaged so that each patient contributed equally to the group analysis.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis

To quantify and describe the specific impact of temperature on phenytoin pharmacokinetics, nonlinear mixed-effects modeling(NONMEM version VII, Icon Development Solutions, Hanover, Maryland) was also employed. This population-based approach can account for differences in drug administration timing and dosage that often occur as part of routine clinical care to determine population parameters (fixed effects) while preserving individual exposure (inter-subject variability – ISV) and residual variability (random effects) despite limited concentration sampling.

Free phenytoin disposition was initially based on a one-compartmental Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetic model that was fit to the unbound concentration-time data:

| (1) |

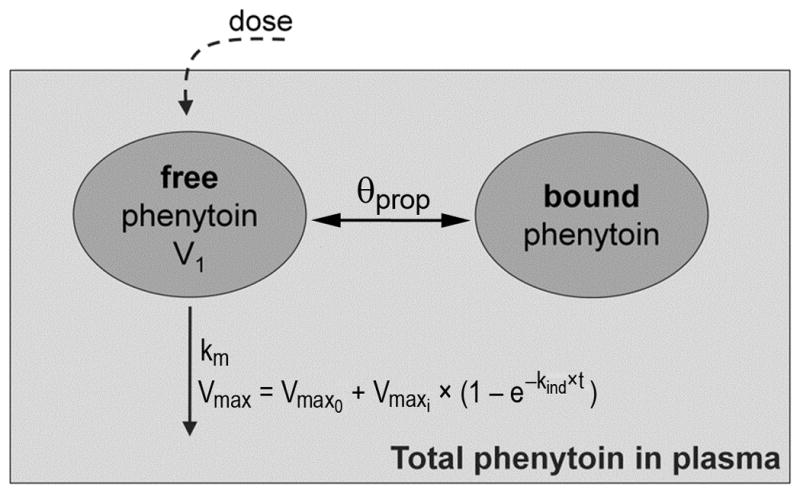

where Vmax is the maximum velocity of metabolism(mg/h), km is the Michaelis-Menten rate constant(mg/L; at half of Vmax), Unb is the amount of free phenytoin(mg), and V1 is the volume of distribution(L). The total phenytoin was included in the model as follows:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Bou is the amount of bound phenytoin(mg) and θprop is the proportionality constant between the bound and unbound drug amounts. The total phenytoin(Totaldrug) is the sum of both Unb and Bou. As the fosphenytoin prodrug is very rapidly and completely converted to phenytoin and 100% bioequivalent following standard IV administration (24), conversion was not incorporated in the model.

Then, a second model (Figure 1) was fit, using the same one-compartmental Michaelis-Menten equation and the additional assumption that Vmax varies as a function of time (Vmax term in equation 1 replaced by Vmax(t) in Equation 4) as previous studies have demonstrated that TBI induces phenytoin metabolism.(18, 20)

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the selected pharmacokinetic model.

Two compartments represent the amount of free phenytoin (unbound) and of bound drug in plasma. V1 is the volume of distribution, θprop is the proportionality constant between the bound and unbound drug amounts, km is the Michaelis-Menten elimination rate constant (mg/L), Vmax is the maximum velocity of metabolism (mg/h), Vmax0 is the time-invariant maximum velocity of metabolism at baseline (mg/h), Vmaxi is the time-dependent velocity defined by the rate constant kind (h−1) and t is time (h). The total amount of phenytoin in plasma is the sum of unbound and bound phenytoin.

| (4) |

where Vmax(t) is the time-variant maximal velocity of metabolism, Vmax0 is the time-invariant maximum velocity of metabolism at baseline(mg/h), and Vmaxi is the component of this velocity impacted by induction defined by the rate constant kind(h−1) and time(h). Model selection and evaluation were completed based on visual inspection of goodness of fit plots, the objective function value provided by NONMEM, and the precision of the parameter estimates (see Supplemental Digital Content).

After base model selection and possible covariance between the random effects was identified, sex, age, weight, height, hypothermic group, and temperature were tested as covariates on each pharmacokinetic parameter. A full model was then developed by combining the covariates individually identified as significant(p<0.001) and refined by backward selection. This procedure and the nonparametric bootstrap analysis used to evaluate pharmacokinetic parameter estimate robustness and reliability is described in the Supplemental Digital Content.

Simulation

The population parameter estimates from the final model were used to simulate phenytoin elimination and Cfree-time profiles of 1000 children receiving standard fosphenytoin dosing (20 mg/kg intravenous followed by 6 mg/kg/day divided every 12h) and either therapeutic hypothermia to 33°C or controlled normothermia. Population median and 90% confidence intervals of these concentrations and the percentage of simulated patients with supratherapeutic levels (above 2 mg/L) over time were determined. In order to avoid weight effects in the parameters, all individuals were simulated at 40kg.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics and temperature management

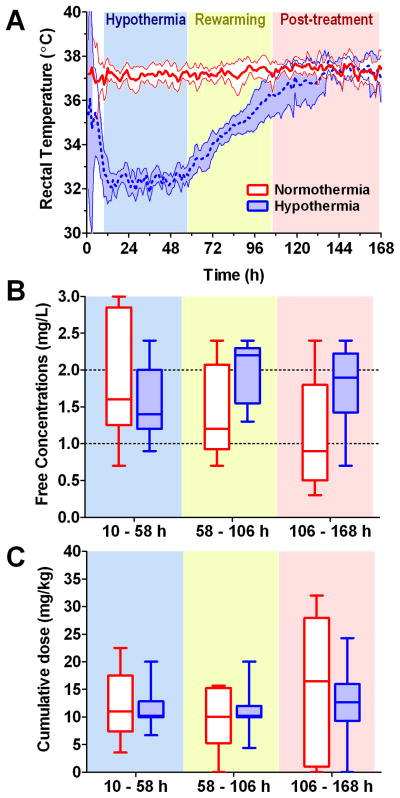

Nineteen children randomized to receive therapeutic hypothermia or normothermia were evaluated. Demographic information is provided in Table 1. The groups had similar sex, age, height, and weight. Although highly variable, the GCS and ISS suggest that injuries may have been worse in the hypothermia group. One patient in each group had the maximum ISS of 75 and the two additional subjects in the hypothermic group had GCS scores of 5 and 4 and ISS scores of 30 and 50, respectively. Barbiturates were administered more commonly in the normothermia (5 of 9 patients) versus hypothermia (3 of 10 patients) groups. No other medications known to interact with phenytoin were administered to any patient. Biomarkers of liver and renal function and serum albumin levels were similar among groups. The high upper ranges of liver enzymes in the normothermia group were driven by a single patient. Figure 2A shows the hourly patient rectal temperatures achieved through the cooling protocol. All patients attained goal temperatures within 10h of injury and were maintained within target ranges.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Normothermia (n = 9) | Hypothermia (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Male - n (%) | 6 (67%) | 5 (50%) |

| Height (cm) - mean (SD) | 142 (29) | 144 (31) |

| Weight (kg) - mean (SD) | 39 (16) | 47 (27) |

| Age (yr) - median (range) | 13.6 (2.5–16.2) | 11.1 (2.1–14.7) |

| GCS - median (range) | 7 (3–7) | 5 (3–8) |

| ISS - median (range) | 21 (16–75) | 33.5 (25–75) |

| Albumin | ||

| Day 1 - mean (SD) | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.5) |

| Day 3 - mean (SD) | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.2) |

| Day 7 - mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.3) | 2.7 (0.4) |

| AST - median (range) | 60 (38–1303) | 41 (31–111) |

| ALT - median (range) | 26 (11–530) | 30 (23–88) |

| ALP - median (range) | 145 (70–382) | 168 (66–288) |

| T. bili - mean (SD) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.6 (0.4) |

| Serum creatinine - mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2) |

Measurements are from the day of admission unless otherwise noted. AST = Aspartate transaminase, ALT = Alanine transaminase, ALP = Alkaline phosphatase, and T. bili = total bilirubin.

Figure 2. Patient temperatures, free phenytoin concentrations, and dosing.

Protocol timing is organized into three shaded periods based on time from injury: hypothermia (or normothermia) from 10 – 58 h; rewarming (if in the hypothermia group) from 58 – 106 h; and post-treatment from 106 – 168 h. A. Hourly patient rectal temperatures demonstrate the success of the study protocol in achieving goal temperatures. Shaded regions are the 95% confidence intervals. B. There was a trend towards elevated free phenytoin concentrations in the hypothermia group in the rewarming and post-treatment periods (temp effect: p=0.051; study period effect: p=0.023; interaction: p=0.633). Dotted lines indicate the therapeutic range of 1– 2 mg/L. Box and whiskers graphs depict the mean, 95% confidence intervals, and range of each group. C. The cumulative dose of fosphenytoin administered to each patient was not different between the groups (temp effect: p=0.853; study period effect: p=0.249; interaction: p=0.660).

Effect of hypothermia on the phenytoin levels and dosing

There were 236 fosphenytoin and 17 phenytoin doses administered over the 168h study period. The majority of children received fosphenytoin exclusively; three patients received phenytoin loading doses and 2 patients received at least one maintenance dose of this medication. There were 121 phenytoin Ctotal and 114 Cfree measured concurrently. Figure 2B shows there was a trend towards elevated phenytoin Cfree in the hypothermia group during the rewarming and post-treatment periods (temp effect: p=0.051; study period effect: p=0.023; interaction: p=0.633). One patient in each group did not have levels drawn in one of the study periods and conservatively were excluded in 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Hypothermia children had a supratherapeutic median Cfree of 2.2 mg/L during rewarming. Five of 9(56%) patients in this period and 6 of 10(60%) patients in the post-treatment period had levels greater than 2 mg/L. In the normothermic group, 3 of 8(38%) and 1 of 7(14%) patients had supratherapeutic levels, respectively. Ctotal followed similar trends (data not shown). Interestingly, Figure 2C demonstrates that the elevated concentrations were not explainable by higher dosing in the hypothermia group (temp effect: p=0.853; study period effect: p=0.249; interaction: p=0.660).

Population pharmacokinetic modeling

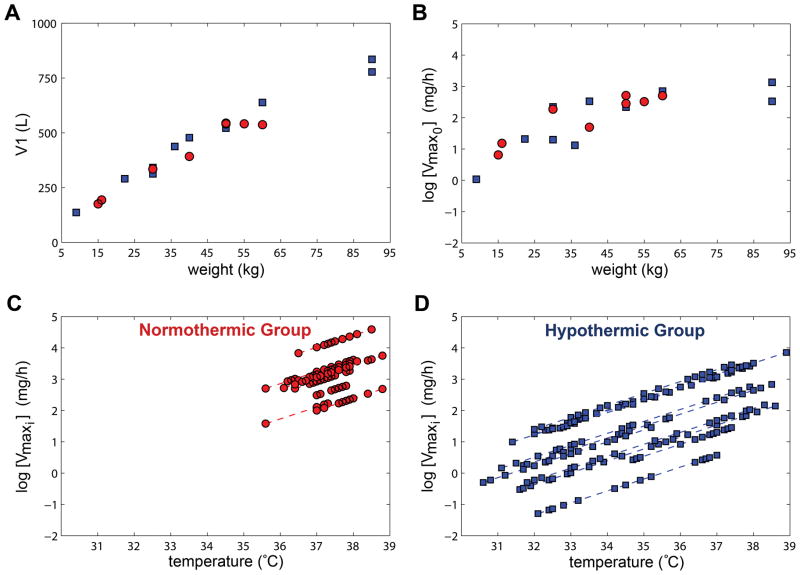

The time-variant Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetic base model was significantly better at describing phenytoin Cfree and Ctotal than the one-compartmental Michaelis-Menten model (objective function value reduction of 81.077 points, p<0.01) and was used for subsequent analyses. No covariance between the random effects identified was significant. Sex, age, and height did not affect any of the parameters. The weight effect on V1 (equation 5) produced a large drop in the NONMEM objective function (44.23 points, p<0.001). The weight covariate also significantly explained part of the identified ISV on Vmax0 parameter (equation 6).

| (5) |

| (6) |

In Equations 5 and 6, θ and η terms are the fixed and random effect parameters, respectively; γwt1 is the weight effect parameter on V1; and wt2 is the weight effect parameter on Vmax0.

At this point, group assignment was not a significant covariate of any pharmacokinetic parameters. However, when temperature was incorporated as a continuous variable in the model (Equation 7), the improvement was significant (p<0.01).

| (7) |

where temp1 quantifies the temperature effect on Vmaxi parameter. Table 2 lists the parameter estimates of the final population pharmacokinetic model with the corresponding relative standard error(RSE%). The goodness of fit plots for Cfree and Ctotal (Figure E1, Supplemental Digital Content) indicate that the data were well described by the model. Data dynamics, as well as their dispersion, were well captured for both Cfree and Ctotal by the model, although the 95th percentile was overpredicted (Figure E2, Supplemental Digital Content). The bootstrapping estimates (Table E1, Supplemental Digital Content) were very close to the final model parameter estimates.

Table 2.

Population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates

| Parameter | Estimate (RSE%) | ISV (RSE%) |

|---|---|---|

| V1 (L) = (weight/40)γwt1×θV1 | γwt1 = 0.809 (9.28) θV1 = 433 (3.57) |

10.1 (50.4) |

| Vmax0 (mg/h) = θVmax0×exp[(weight-40)×wt2] | θVmax0 = 6.73 (22.8) wt2 = 0.0298 (33.6) |

55.0 (47.1) |

| Vmaxi (mg/h) = θVmaxi×exp[(temp-37)×temp1] | θVmaxi = 11.6 (119) temp1 = 0.381 (51.5) |

110 (88.2) |

| km (mg/L) | 0.483 (53.37) | |

| θprop (unitless) | 8.15 (3.9) | 15.2 (51.3) |

| kind (h−1) | 0.00426 (97.2) | |

| Log residual error Cfree (mg/L) | 0.0372 (47.6) | |

| Log residual error Ctotal (mg/L) | 0.0144 (20.0) |

Model pharmacokinetic estimates, equations describing their relationships with covariates, and their corresponding relative standard error (RSE %) from the final full model. ISV = inter-subject variability expressed as coefficient of variation (%); θ terms are the fixed effect parameters, V1 = apparent volume of distribution; γwt1 = weight effect parameter on V1; Vmax0 = time-invariant maximum velocity of metabolism at baseline; wt2 = weight effect parameter on Vmax0; Vmaxi = time-dependent velocity defined by the rate constant kind and time t; temp1 = temperature effect parameter on Vmaxi; km = Michaelis-Menten elimination rate constant; θprop = proportionality constant for the bound phenytoin; kind = rate constant for induction of metabolism. The phenytoin fraction unbound (reciprocal of θprop) was 0.123±0.005.

Figure 3 shows the impact of covariates on the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters for each patient in the final time-variant model. The estimated V1 and Vmax0 are both positively-correlated with patient weight and cooling reduces the estimated Vmaxi values for patients in the normothermic and hypothermic groups. Importantly, therapeutic hypothermia led to a 4.6-fold (11.6 to 2.53mg/h) decrease in Vmaxi at 33°C versus 37°C. The resulting impact on maximal velocity of metabolism (Vmax0+Vmaxi) is a reduction of 49.5%.

Figure 3. Impact of covariates on the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters.

Circles(red) and squares(blue) are patients in the normothermic and hypothermic groups, respectively. A/B. Estimates of volume distribution (V1) and time-invariant maximum velocity of metabolism at baseline (Vmax0) for each patient is positively-correlated with weight. C/D. Estimated time-dependent velocity of metabolism (Vmaxi) on the log scale is reduced with lower temperatures for the normothermic and hypothermic patients versus temperature.

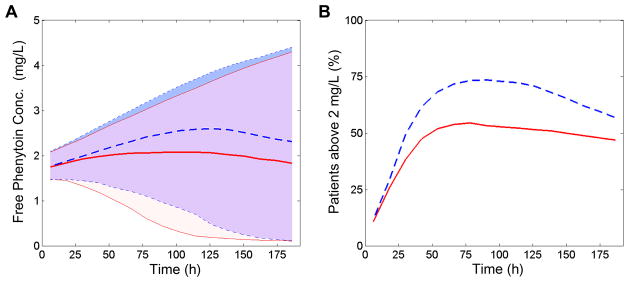

Simulation of temperature effects

The successful modeling provided an opportunity to simulate the magnitude and timing of therapeutic hypothermia’s effect on phenytoin elimination, concentrations, and risk of toxicity. Forty-eight hours of 33°C hypothermia followed by slow rewarming reduced phenytoin elimination nearly 50% during the cooling and rewarming periods (Figure E3, Supplemental Digital Content) leading to elevated median Cfree predominantly during the rewarming period (Figure 4). This effect of therapeutic hypothermia on phenytoin Cfree persisted well beyond the end of the temperature management protocol. A greater proportion of simulated children in the hypothermic group had a phenytoin Cfree above the range commonly reported as a toxicity threshold (approximately 50% more patients had a level greater than 2mg/L).

Figure 4. The magnitude and timing of the effects of temperature on free phenytoin concentrations.

Simulations of 1000 children receiving either therapeutic hypothermia or controlled normothermia. Solid lines/lightest(red) shading represents the normothermic group while dashed lines/darkest(blue) shading represents the hypothermic group. The simulated fosphenytoin dosing schedule was 20 mg/kg IV loading dose followed by 6 mg/kg/day divided every 12 h. The cooling protocol involved hypothermia induction over 6 h to 33 °C, hold at 33 °C for 48 h, and then slow rewarming (1 °C per 24 h) to 37 °C (depicted in Figure E3, Supplemental Digital Content). Controlled normothermia patients were fixed at 37 °C. All individuals were simulated with a weight of 40 kg. A. Unbound phenytoin concentrations are elevated in patients receiving hypothermia versus normothermia as shown by the population predicted median (lines) and 90% confidence interval (shading) over time. B. Percentage of simulated children with free phenytoin concentrations above the 2 mg/L toxicity threshold in each group versus time.

DISCUSSION

We report that therapeutic hypothermia, as applied in the setting of a large RCT for pediatric TBI, significantly reduces phenytoin elimination. A trend towards elevated drug concentrations, particularly during rewarming, was observed in children randomized to hypothermia despite similar dosing as normothermic children. Population pharmacokinetic modeling demonstrated that therapeutic hypothermia decreased Vmaxi; the parameter describing the time-dependent increase in phenytoin metabolism that occurs following TBI. Simulations predict that the increased risk for drug toxicity extends many days beyond the end of cooling. Unexpected medication dose-concentration relationships may have important implications in children receiving therapeutic hypothermia.

The non-linear mixed effects modeling fit the clinical data well and the pharmacokinetic parameter estimates obtained from the final time-variant model are consistent with published values. TBI is known to induce drug metabolism in adults 4–14 days after injury (25). Several clinical studies have similarly reported subtherapeutic phenytoin concentrations receiving standard dosing regimens or higher than expected phenytoin metabolism in TBI patients (18–20, 26). O’Mara et al. modeled Ctotal of 16 children and reported elevated phenytoin metabolism than previously established for children with epilepsy; Km values were lower (meaning a greater enzyme affinity) and Vmax values were higher (meaning greater enzyme capacity) (19, 27). Similarly, both McKindley et al. and Stowe et al. found Michaelis-Menton models that incorporated a time-variant Vmax term best fit the majority of Cfree in the ~10 adult and pediatric patients, respectively. In our study of 19 children, the Vmaxi (estimate±SEM; 11.6±13.8 mg/h) was larger than the Vmax0 (6.73±1.53 mg/h) suggesting that the induced component of metabolism is an important contributor to the overall metabolism.

Cooling significantly decreased phenytoin elimination suggesting concentrations will be elevated clinically despite standard medication dosing. Small clinical and preclinical studies in adults have shown that levels of medications metabolized by CYP such as midazolam (28–30), fentanyl (31), and vecuronium (32) are elevated during cooling. In the only other pediatric RCT, Roka et al. showed that infants with HIE who were randomized to 33–34°C for 72h had a ~40% increase in morphine concentrations at the end of cooling and more often had a potentially toxic level (above 300 ng/mL) (33). The only pediatric clinical data involving phenytoin is from a single case report that reported Vmax was decreased from 12.5 mg/h at 37.3°C to 1.2 mg/h at 33°C (34). In adults, Iida et al. administered phenytoin to 14 patients with brain injury and reported significantly higher concentration-time profiles during hypothermia and a 50% decreased phenytoin elimination rate (35). Unfortunately, without randomization, this study design was unable to separate temperature-related recovery of metabolic capacity with rewarming from a parallel, injury-related enzymatic induction. With the current RCT data, we report hypothermia to 32–33 °C decreased phenytoin Vmaxi 4.6-fold and reduced the overall Vmax after induction by ~50%, but did not affect Km. This suggests that cooling specifically decreases overall phenytoin metabolic capacity by partially reversing the induction in metabolism that occurs in children with TBI. Our study was not designed to identify the mechanism driving this phenomenon, but possibilities include a direct effect on CYP2C9/19 and/or an interaction with injury processes leading to enzyme induction. Two recent reviews thoroughly detail the evidence for therapeutic hypothermia impacting drug pharmacokinetics through these processes (13, 36). Given the clinical data demonstrating an impact of cooling on metabolized drugs in HIE patients (33) and healthy volunteers (29, 32) and established interactions between hypothermia and other disease processes that also impact drug metabolism such as cardiac arrest (30), it is likely that the current findings will be relevant to the clinical care of other hypothermia patients who receive phenytoin products.

The magnitude and timing of the altered pharmacokinetics resulting from therapeutic hypothermia is important clinically. With phenytoin, dose-concentration relationships are already very difficult to predict due to its narrow therapeutic range, nonlinear pharmacokinetics, and the abundance of clinical covariates in critically ill patients (37). We demonstrate that cooling children to 32–33°C for 48h with slow rewarming increased the proportion of children with supratherapeutic levels not during the cooling period, but during rewarming. Further, because of phenytoin’s long half-life, the effect persisted at least 5 days beyond the end of the cooling period. This creates an extended time period of potentially unexpected drug responses after the active cooling period that may not be appreciated by clinicians. Intravenous phenytoin therapy is known to produce cardiac and neurological adverse drug reactions (38). Although hypotension and bradycardia are commonly attributed to rapid infusion of its propylene glycol diluent, bradydysrhythmias have also been reported with fosphenytoin (39). Whether medication adverse reactions impacts hypothermia-related outcomes in study populations where polypharmacy is common, such as TBI, is unknown, but warrants further investigation. The incorporation of pharmacokinetic endpoints and well-defined adverse reaction monitoring in future hypothermia RCTs would allow investigators to isolate the direct results of cooling versus its potential interactions with concurrent therapy (40).

The primary limitation of our study was its sample size. This precluded associations of levels with clinical endpoints and evaluations of the impact of additional covariates such as nutritional support, injury severity, and concomitant medications. The current study, however, is notable because it was conducted in the setting of a well-controlled RCT and is among the largest pharmacokinetic studies published in children. Traditional pharmacokinetic studies with intensive sampling of concentrations are often not feasible in critically-ill pediatric populations. Our approach was also innovative as it simultaneously fit the hundreds of Ctotal and Cfree measured as part of routine clinical care using robust nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. We show that hypothermia significantly decreases phenytoin metabolism and identified time window of greatest concern. Results should be confirmed and correlated with relevant clinical parameters in larger populations and in children receiving cooling for other conditions such as in the recently proposed PharmaCool multicenter study (41).

CONCLUSIONS

We report therapeutic hypothermia significantly reduces phenytoin elimination in children with severe TBI leading to increased drug levels for an extended period of time after cooling. Regardless of efficacy of therapeutic hypothermia in the Cool Kids trial, children will continue to receive this treatment for a variety of disorders; therefore understanding the impact of therapeutic hypothermia on drug disposition is necessary to optimize its application and prevent drug toxicity.

Supplementary Material

Table E1. Bootstrap analysis

Figure E1. Model goodness-of-fit plots

Figure E2. Visual predictive checks of the pharmacokinetic model

Figure E3. Simulation of the effects of temperature on phenytoin elimination

Acknowledgments

Grant support was provided by the National Institutes of Health awards U01NS052478 (PDA), KL2TR000146 (PEE), and P01NS030318 (PMK). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Poloyac has received travel support from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Dr. Bies has received grant support from Indiana CTSI through a gift of Eli Lilly and Company. He has received payment for lectures from NIGMS and has received travel reimbursements from Indiana CTSI, Uppsala University, and NIAID/NIDA. Dr. Kochanek has received grant support from the Laerdal Foundation and has multiple patents from United States Provisional Patent and CMU Invention Disclosure. Dr. Adelson has received grant support from Integra Life Sciences and Codman. He has received consulting fees from Tramatec.

The authors thank the investigators and institutions from the Pediatric TBI Consortium (PTBIC) that participated in the “Cool Kids Trial” for providing access to the patient data necessary to conduct this ancillary study. We also thank Jiangquan Zhou, PhD for her contribution to the pharmacokinetic modeling.

Pediatric TBI Consortium Sites and Co-Investigators

USA

Carolinas Medical Center - W Tsai, D Bailey, D Anderson

Children’s Hospital Of Philadelphia – S Friess, N Thomas

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital – K Bierbrauer, N Walz

Cohen’s Children’s Hospital – S Schneider, R Pachilkis

Duke University – G Grant, K Gustafson

Penn State University – N Thomas, Cf Craig

Phoenix Children’s Hospital- S Buttram, Pd Adelson, M Lavoie, J Blackham

University Of California – Davis – JP Muizelaar, M Zwienenberg-Lee, S Farias

University Of Miami – J Ragheb, B Levin

University Of Pittsburgh- M Bell, S Beers, S Wisniewski

University Of Texas, Southwestern – Children’s Hospital of Dallas - P Okada, P Stavinoha

University Of Washington – R Ellenbogen

Washington University – J Pineda, D White

New Zealand

Starship Children’s Hospital – J Beca, K Murrell

Australia

Princess Margaret Hospital – S Erickson, C Pestell

Footnotes

The rest of the authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bernard SA, Gray TW, Buist MD, et al. Treatment of comatose survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with induced hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Study Group. Mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):549–556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azzopardi DV, Strohm B, Edwards AD, et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eicher DJ, Wagner CL, Katikaneni LP, et al. Moderate hypothermia in neonatal encephalopathy: efficacy outcomes. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32(1):11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gluckman PD, Wyatt JS, Azzopardi D, et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9460):663–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clifton GL, Miller ER, Choi SC, et al. Lack of effect of induction of hypothermia after acute brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(8):556–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102223440803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifton GL, Valadka A, Zygun D, et al. Very early hypothermia induction in patients with severe brain injury (the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia II): a randomised trial. Lancet neurology. 2011;10(2):131–139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70300-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marion DW, Penrod LE, Kelsey SF, et al. Treatment of traumatic brain injury with moderate hypothermia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(8):540–546. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchison JS, Ward RE, Lacroix J, et al. Hypothermia therapy after traumatic brain injury in children. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2447–2456. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifton GL, Choi SC, Miller ER, et al. Intercenter variance in clinical trials of head trauma--experience of the National Acute Brain Injury Study: Hypothermia. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(5):751–755. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.5.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kochanek PM, Carney N, Adelson PD, et al. Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents--second edition. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13 (Suppl 1):S1–82. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31823f435c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tortorici MA, Kochanek PM, Poloyac SM. Effects of hypothermia on drug disposition, metabolism, and response: A focus of hypothermia-mediated alterations on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9):2196–2204. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000281517.97507.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Poloyac SM. The effect of therapeutic hypothermia on drug metabolism and response: cellular mechanisms to organ function. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7(7):803–816. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.574127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis RJ, Yee L, Inkelis SH, et al. Clinical predictors of post-traumatic seizures in children with head trauma. Annals of emergency medicine. 1993;22(7):1114–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80974-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temkin NR, Dikmen SS, Wilensky AJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind study of phenytoin for the prevention of post-traumatic seizures. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(8):497–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199008233230801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vozeh S, Muir KT, Sheiner LB, et al. Predicting individual phenytoin dosage. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1981;9(2):131–146. doi: 10.1007/BF01068078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKindley DS, Boucher BA, Hess MM, et al. Effect of acute phase response on phenytoin metabolism in neurotrauma patients. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 1997;37(2):129–139. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Mara NB, Jones PR, Anglin DL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of phenytoin in children with acute neurotrauma. Crit Care Med. 1995;23(8):1418–1424. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199508000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stowe CD, Lee KR, Storgion SA, et al. Altered phenytoin pharmacokinetics in children with severe, acute traumatic brain injury. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2000;40(12 Pt 2):1452–1461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adelson PD, Bratton SL, Carney NA, et al. Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4(3 Suppl):S1–75. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000067635.95882.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adelson PD, Ragheb J, Kanev P, et al. Phase II clinical trial of moderate hypothermia after severe traumatic brain injury in children. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(4):740–754. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000156471.50726.26. discussion 740–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis Parke. FDA Approved Labeling. Nov 27, 12. ANDA 084349: Dilantin (extended phenytoin sodium capsules, USP) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boucher BA. Fosphenytoin: a novel phenytoin prodrug. Pharmacotherapy. 1996;16(5):777–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boucher BA, Kuhl DA, Fabian TC, et al. Effect of neurotrauma on hepatic drug clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;50(5 Pt 1):487–497. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frend V, Chetty M. Dosing and therapeutic monitoring of phenytoin in young adults after neurotrauma: are current practices relevant? Clinical neuropharmacology. 2007;30(6):362–369. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318059ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer LA, Blouin RA. Phenytoin Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetics in Caucasian paediatric patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1983;8(6):545–549. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198308060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukuoka N, Aibiki M, Tsukamoto T, et al. Biphasic concentration change during continuous midazolam administration in brain-injured patients undergoing therapeutic moderate hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2004;60(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hostler D, Zhou J, Tortorici MA, et al. Mild Hypothermia Alters Midazolam Pharmacokinetics in Normal Healthy Volunteers. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(5):781–788. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J, Empey PE, Bies RR, et al. Cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia decrease isoform-specific cytochrome P450 drug metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39(12):2209–2218. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Empey P, Melick J, Poloyac S, et al. Mild hypothermia decreases fentanyl and midazolam steady-state clearance in a rat model of cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1221–1228. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823779f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell JE, Heier T, Wright PM, et al. Temperature-dependent pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of vecuronium. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(1):84–93. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200001000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roka A, Melinda KT, Vasarhelyi B, et al. Elevated morphine concentrations in neonates treated with morphine and prolonged hypothermia for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e844–849. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson BJ. Phenytoin elimination in a child during hypothermia for traumatic brain injury. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 2005;6(3):133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iida Y, Nishi S, Asada A. Effect of mild therapeutic hypothermia on phenytoin pharmacokinetics. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23(3):192–197. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou J, Poloyac SM. The effect of therapeutic hypothermia on drug metabolism and response: cellular mechanisms to organ function. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011 doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.574127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Winckelmann SL, Spriet I, Willems L. Therapeutic drug monitoring of phenytoin in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(11):1391–1400. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.11.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. Dilantin (phenytoin sodium) [package insert] New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adams BD, Buckley NH, Kim JY, et al. Fosphenytoin may cause hemodynamically unstable bradydysrhythmias. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2006;30(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanchez de Toledo J, Bell MJ. Complications of hypothermia: interpreting ‘serious,’ ‘adverse,’ and ‘events’ in clinical trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(3):439–441. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c510e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Haan TR, Bijleveld YA, van der Lee JH, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medication in asphyxiated newborns during controlled hypothermia. The PharmaCool multicenter study. BMC pediatrics. 2012;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table E1. Bootstrap analysis

Figure E1. Model goodness-of-fit plots

Figure E2. Visual predictive checks of the pharmacokinetic model

Figure E3. Simulation of the effects of temperature on phenytoin elimination