Abstract

Objective

To examine whether an empirically and theoretically derived treatment combining mindfulness- and acceptance-based strategies with behavioral approaches would improve outcomes in GAD over an empirically-supported treatment.

Method

This trial randomized 81 individuals (65.4% female, 80.2% identified as White, average age 32.92) diagnosed with GAD to receive 16 sessions of either an Acceptance Based Behavior Therapy (ABBT) or Applied Relaxation (AR). Assessments at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 6-month follow-up included the following primary outcome measures: GAD Clinician Severity Rating, Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, and the State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Secondary outcomes included the Beck Depression Inventory-II, Quality of Life Inventory, and number of comorbid diagnoses.

Results

Mixed Effect Regression Models showed significant large effects for Time for all primary outcome measures (d’s 1.36 to 1.61) but non-significant, small effects for Condition and Condition X Time (d’s 0.002 to 0.24), indicating clients in both treatments improved comparably over treatment. For secondary outcomes, Time was significant (d’s 0.74 to 1.38) but Condition and Condition X Time effects were not (d’s 0.11 to 0.31). No significant differences emerged over follow-up (d’s 0.02 to 0.16) indicating maintenance of gains. Between 63.3 and 80.0% of clients in ABBT and 60.6 and 78.8% of clients in AR experienced clinically significant change across 5 calculations of change at post-treatment and follow-up.

Conclusions

ABBT is a viable alternative for treating GAD.

Keywords: acceptance-based treatment, behavior therapy, mindfulness, acceptance

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a chronic anxiety disorder associated with high comorbidity (Bruce, Machan, Dyck, & Keller, 2001), reduced quality of life (Hoffman, Dukes, & Wittchen, 2008) and significant health care utilization (Hoffman et al., 2008). Meta-analyses reveal that cognitive behavioral therapies are efficacious for GAD (Borkovec & Ruscio, 2001; Covin, Ouimet, Seeds, & Dozois, 2008). However, GAD remains one of the least successfully treated of the anxiety disorders (Waters & Craske, 2005), with most studies finding that fewer than 65% of clients meet criteria for high end-state functioning at post-treatment (e.g., Ladouceur et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2011) and few studies examining the impact of treatment on quality of life.

Several researchers have aimed to refine and expand existing models of GAD in an effort to more clearly identify causal and maintaining factors to target in therapy (see Behar, DiMarco, Hekler, Mohlman, & Staples, 2009, for a review). Recent randomized controlled trials informed by these models indicate that targeting intolerance of uncertainty (Dugas et al., 2010), and the interpersonal and emotion focused aspects of GAD (Newman et al., 2011) yield effects comparable to existing CBTs for GAD. A small pilot study found that targeting meta-cognition in GAD (Wells et al., 2010) produced better outcomes than applied relaxation, however, the very low rates of response to applied relaxation, coupled with the small sample size, indicate a need for further research to confirm this finding.

Roemer and Orsillo (2002) developed a model of GAD informed by research and theory highlighting the potential roles of experiential avoidance (e.g., Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette & Strosahl, 1996) and ruminative, self-critical processing (e.g., Barnard & Teasdale, 1991) in the development and maintenance of psychopathology. Supported by research comparing individuals with and without GAD, this model suggests that those with GAD have a problematic relationship with their internalized experiences characterized by a narrowed attention toward threat (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007), and a critical, judgmental reactivity toward their emotional responses (e.g., Lee, Orsillo, Roemer, & Allen, 2010; Llera & Newman, 2010; Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005) and thoughts (Wells & Carter, 1999). This reaction to internal experiences motivates individuals with GAD to engage in experiential avoidance (e.g., Lee et al., 2010) using a variety of strategies including worry, the central defining feature of GAD. Although worry decreases somatic arousal and helps to distract an individual from more emotional topics (see Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004, for a review), rigid habitual efforts at experiential avoidance can paradoxically increase distress (e.g., Hayes et al., 1996), leading to a cycle of reactivity and avoidance that in turn affects behavior. Individuals with GAD are less likely to consistently engage in behaviors that are important to them (i.e., valued actions) and as a result experience a diminished quality of life (Michelson, Lee, Orsillo, & Roemer, 2011).

This model led to the development of an acceptance based behavior therapy for GAD (ABBT; Roemer & Orsillo, 2009; Roemer & Orsillo, In press), a flexible treatment adapted from traditional CBT for GAD (e.g., Borkovec et al., 2004), as well as other acceptance-based behavioral therapies including Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993), that explicitly target these mechanisms1. Specifically, this ABBT aims to help clients to cultivate an expanded (as opposed to narrowed, threat-focused) awareness along with a compassionate (as opposed to judgmental) and decentered (as opposed to seeing thoughts and feelings as all-encompassing indicators of truth) stance towards internal experiences. These new skills reduce rigid experiential avoidance, as does the explicit promotion of an accepting and willing stance towards internal experiences. Behavioral avoidance and constriction are targeted by encouraging clients to identify and mindfully engage in personally meaningful actions. ABBT uses empathic validation, self-monitoring, formal and informal mindfulness exercises, encouragement of acceptance through psychoeducation and experiential exercises, and writing and behavioral exercises that apply these skills to personally meaningful activities (see Roemer & Orsillo, 2009; in press, for a more detailed presentation of the treatment).

Data from an open trial (Roemer & Orsillo, 2007) and waitlist RCT (Roemer, Orsillo, & Salters-Pedneault, 2008) indicate significant effects on clinician-rated and self-report symptom measures of anxiety and depression, as well as self-reported quality of life and high rates of end-state functioning. Clients receiving ABBT report significant decreases in experiential avoidance (Roemer et al., 2008), distress about emotional responses, and intolerance of uncertainty (Treanor, Erisman, Salters-Pedneault, Orsillo, & Roemer, 2011) and significant increases in values-consistent behavior (Michelson et al., 2011). Moreover, both the time spent accepting internal experiences and engaging in valued activities significantly predict outcome (Hayes, Orsillo, & Roemer, 2010) providing support for the proposed mechanisms of action. However, studies are needed that compare this treatment to a credible, efficacious alternative therapy.

Other acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments have also been tested for GAD. A recent study comparing ACT to CBT (with behavioral exposures in both conditions) showed comparable effects of the two treatments, with the 14 individuals with GAD who received ACT demonstrating medium to large effects on outcome measures (Arch et al., 2012). Similarly, in a study of older adults with GAD, the seven individuals receiving ACT demonstrated large effect sizes on outcome measures, which were comparable to the nine individuals receiving CBT in this study (Wetherell et al., 2011). A recent meta-analysis demonstrated the promise of mindfulness-based interventions in reducing anxiety generally (Hofmann, Sawyer, Witt, & Oh, 2010), and two preliminary trials of MBCT suggest an effect of treatment on self-reported GAD symptoms (Craigie, Rees, Marsh, & Nathan, 2008; Evans et al., 2008), although outcomes fell short relative to other GAD treatment trials. Unlike ACT and ABBT, MBCT did not incorporate behavioral strategies, which may partly explain the more modest effects.

While findings for ABBT are promising, previous studies were limited by absence of an active control condition and modest sample sizes. To more rigorously test ABBT, this study compared ABBT to an established and efficacious treatment, Applied Relaxation (AR). AR is an empirically supported treatment for GAD (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001) and is recommended in the NICE clinical guideline 113 (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care, 2011). This status comes from several methodologically rigorous studies that have examined the efficacy of AR. For example, randomized controlled trials demonstrated that AR was more efficacious than a nondirective, reflective listening therapy (Borkovec & Costello, 1993) and roughly as efficacious as cognitive therapy (Arntz, 2003; Öst & Breitholtz, 2000), cognitive behavioral therapy (Borkovec & Costello, 1993; Dugas et al., 2010), and worry exposure (Hoyer et al., 2009) in treating GAD. Further supporting the efficacy of AR, a meta-analysis by Siev and Chambless (2007) found that cognitive therapy and relaxation therapy were equivalent treatments for GAD. AR is also straightforward and relatively easy to learn, which increases the probability that therapists can deliver it with good adherence and competence.

In the spirit of a comparative efficacy trial, we hypothesized that both ABBT and AR would lead to statistically and clinically significant change but that ABBT would be more efficacious than AR on measures of anxiety and quality of life. Additionally, because the processes targeted in ABBT are presumed to underlie many forms of psychopathology, we hypothesized that ABBT would be associated with greater decreases in depression and comorbidity than AR. Finally, we hypothesized that the treatments would be comparably credible and acceptable to participants.

Methods

Participants

The majority of participants were recruited from treatment-seeking individuals at [location removed for blinding] between 2007 and 2010. Potential participants were referred to this study if they received a principal diagnosis of GAD on an intake diagnostic interview (Anxiety Disorders Interview Scheduled for DSM-IV, ADIS-IV, DiNardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994). In addition, 2 participants were referred after being ruled out of a study for panic disorder treatment due to a principal diagnosis of GAD and 5 participants were directly referred to the study from practitioners in the community. Participants were eligible for this study if they: a) received a principal diagnosis of GAD on the ADIS-IV with at least moderate severity (4) on the Clinician Severity Rating; b) reported a GAD onset that preceded their first MDD episode; c) were stable on any medications for three months, were willing to maintain current psychotropic medication levels and to refrain from other psychosocial treatments for anxiety or mood problems during the course of therapy; d) were fluent in English; and e) were 18 years or older. Exclusion criteria were due to clinical considerations: diagnoses of comorbid bipolar disorder, a psychotic disorder, an autism-spectrum disorder, or current substance dependence. Eligibility was primarily assessed by an independent assessor (IA) who conducted the diagnostic assessment. However, inclusion and exclusion criteria were confirmed by a study therapist.

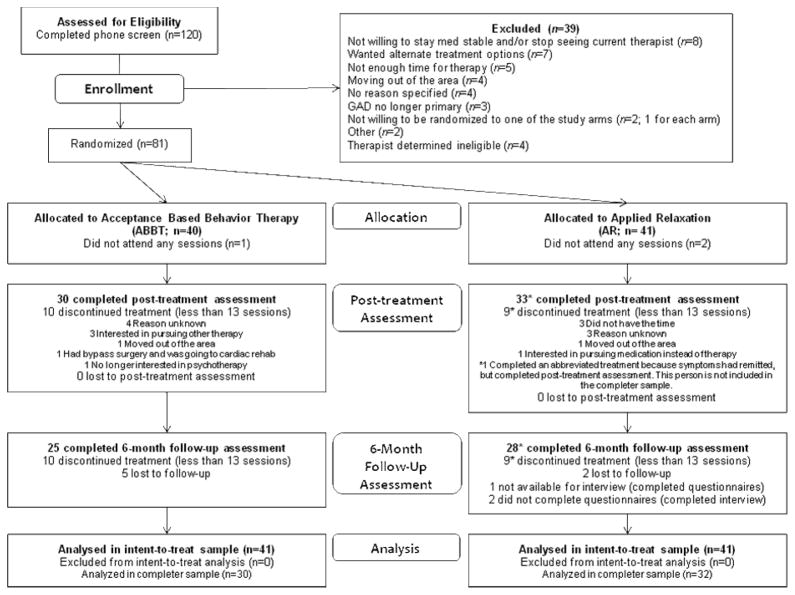

The participant flowchart (Figure 1) shows the number of participants at each stage. One hundred and twenty participants were contacted for a phone screen following their initial assessment to further determine eligibility and interest in the study. Eighty-five participants met eligibility by IA interview, but 4 were excluded by the therapist, in consultation with the supervisors, because they did not meet criteria (2 were not stable on medications and 2 did not have GAD as a principal diagnosis). Thus, 81 participants met inclusion/exclusion criteria, consented to the study, and were randomized. Of the 81 participants, 63 were considered treatment completers2. A research assistant determined the treatment assignment by randomly allocating conditions to participant identification numbers using a random integer generator while forcing even distribution in each block of eight participants at the commencement of the study. Slips of paper linking ID numbers and conditions were then concealed from all study staff; the therapist drew the appropriate slip after participant consent. Forty participants were randomized to ABBT and 41 to AR. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between conditions on demographic variables, psychotropic medication, previous therapy, or the presence of comorbid diagnoses.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

| ABBT (n = 40) | AR (n = 41) | χ2 or F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 33.30 (12.42) | 32.56 (12.05) | 0.07 | .79 |

| Gender | 1.03 | .31 | ||

| Women | 60.0% (n = 24) | 70.7% (n = 29) | ||

| Men | 40.0% (n = 16) | 29.3% (n = 12) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity* | 0.38 | .54 | ||

| White | 77.5% (n = 31) | 82.9% (n = 34) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino(a) | 10.0% (n = 4) | 7.3% (n = 3) | ||

| Asian | 2.5% (n = 1) | 7.3% (n = 3) | ||

| Black | 5.0% (n = 2) | 2.4% (n = 1) | ||

| Middle Eastern | 2.5% (n = 1) | 0.0% (n = 0) | ||

| Biracial (Asian & White) | 2.5% (n = 1) | 0.0% (n = 0) | ||

| Previous Psychotherapy | 0.002 | .97 | ||

| Yes | 85.0% (n = 34) | 85.4% (n = 35) | ||

| No | 15.0% (n = 6) | 14.6% (n = 6) | ||

| Previous CBT/Skills-based Therapy | 0.004 | .95 | ||

| Yes | 22.5% (n = 9) | 22.0% (n = 9) | ||

| No | 75.0% (n = 30) | 75.6% (n = 31) | ||

| Taking Psychotropic Medication | 2.51 | .28 | ||

| Yes | 22.5% (n = 9) | 34.1% (n = 14) | ||

| No | 77.5% (n = 31) | 63.4% (n = 26) | ||

| SSRIs | 10.0% (n = 4) | 22.0% (n = 9) | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 15.0% (n = 6) | 4.9% (n = 2) | ||

| TCAs | 2.5% (n = 1) | 4.9% (n = 2) | ||

| Othera | 5.0% (n = 2) | 4.9% (n = 2) | ||

| Additional Diagnoses | 1.63 | .20 | ||

| Yes | 62.5% (n = 25) | 75.6% (n = 31) | ||

| No | 37.5% (n = 15) | 24.4% (n = 10) | ||

| Social Anxiety | 42.5% (n = 17) | 48.8% (n = 20) | ||

| Major Depression | 7.5% (n = 3) | 17.1% (n = 7) | ||

| Panic Disorder w/Ag | 7.5% (n = 3) | 17.1% (n = 7) | ||

| Specific Phobia | 10.0% (n = 4) | 4.9% (n = 2) | ||

| Eating Disorder NOS | 2.5% (n = 1) | 12.2% (n = 5) | ||

| OCD | 5.0% (n = 2) | 0.0% (n = 0) | ||

| PTSD | 2.5% (n = 1) | 2.4% (n = 1) | ||

| Otherb | 12.5% (n = 5) | 2.4% (n = 1) |

Note. ABBT = acceptance-based behavior therapy; AR = applied relaxation; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant; NOS = not otherwise specified; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; PTSD = post traumatic stress disorder.

Given the small sample size of individual groups, compared those who did and did not identify as White across treatments.

Other medications = SNRI, Buspar, Trazadone, and Propanalol.

Other additional diagnoses = dysthymia, panic disorder w/o agoraphobia, depressive disorder NOS, ADHD, impulse control NOS, and sexual disorder NOS

Primary Outcome Measures (chosen to allow for comparisons to other GAD treatment trials)

ADIS-IV (DiNardo, Brown, & Brown, 1994) is a semi-structured diagnostic interview used to determine current and lifetime DSM-IV diagnostic status. For GAD, the ADIS-IV has demonstrated adequate reliability (κ = .67; Brown, DiNardo, Lehmann, & Cambell, 2001). Independent assessors gave the ADIS-IV-L (lifetime version) at pre-treatment and the ADIS-IV (current) at the post-treatment and follow-up assessments. Both versions include a clinician’s severity rating (CSR; ranging from 0 to 8, with 4 or greater clinically significant) for each diagnosis received. Independent assessors were post-doctoral fellows or graduate students, unaware of treatment condition, trained in the administration and scoring of the ADIS3. Diagnoses were confirmed in a consensus meeting with a doctoral-level psychologist (removed for blinding) and by therapists. Additionally, 30% of interviews were scored by a second rater, with an interclass correlation (ICC) between raters on CSR for GAD of .73.

Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A; Shear et al., 2001) provides a reliable, valid structured format for administering the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS; Hamilton, 1959), a widely used 14-item interviewer administered measure of anxiety. In this sample, internal consistencies were .76 at pre and .82 at both post and follow-up. Post-doctoral fellows or doctoral students, after training, administered the measure, and 15% were rated twice for interater reliability, revealing an ICC of .89.

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ: Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990) is a widely used, reliable, valid 16-item self-report measure of trait levels of worry. In this sample, the internal consistencies were .82 at pre, .90 at post, and .92 at follow-up.

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale – 21-item version (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) has separate, reliable and valid self-report scales for depression, anxiety (i.e., anxious arousal), and stress (i.e., general anxiety and tension) (Antony, Bieling et al., 1998). We used the Stress subscale as an outcome measure because it discriminates between clients with GAD and those with panic disorder, social phobia, and specific phobia (Brown, Chorpita, Korotitsch, & Barlow, 1997). The Stress subscale had internal consistencies of .80 at pre, .88 at post, and .85 at follow-up. Scores were doubled to be comparable to the 42-item version.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Trait Form Y (STAI; Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983) is a reliable, valid 20-item self-report measure that assesses trait levels of anxiety. Internal consistencies were .88 at pre, .95 at post, and .94 at follow-up.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Beck Depression Inventory – II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item self-report measure assessing current levels of depression. In this sample, the internal consistencies were .91 at pre, .95 at post, and .95 at follow-up.

Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, Cornwell, Villanueva, & Retzlaff, 1992) is a 32-item self-report measure assessing the degree of importance and level of satisfaction with each of 16 areas of life. Internal consistencies were .80 at pre, .86 at post and follow-up in this sample.

Treatment Process Measures

Credibility/Expectation Scales (Borkovec & Nau, 1972) was given at the end of the first session.

Working Alliance Inventory – short (WAI-S; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1998) is a reliable, valid 12-item measure of client and therapist perceptions of the agreement in the goals and tasks of therapy as well as the therapeutic bond that was given after session 4 in this study. The internal consistencies were .92 for clients and .91 for therapists.

Reaction to Treatment. During the post-treatment assessment, clients used a 9-point Likert scale to rate the extent to which the treatment was a good match to them.

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the [removed for blinding] University Internal Review Boards as well as by a Data Safety and Monitoring Board. All participants provided informed consent for the study. Participants were enrolled in this study following completion of the ADIS and a phone screen to determine eligibility. Participants received therapy free of charge and were paid $50 each for completing post-treatment and 6-month follow-up assessment.

Interventions

Both treatments were 16 sessions in length, with four initial weekly 90 minute sessions followed by weekly 60 minute sessions and a biweekly taper between sessions 14, 15, and 16. Prior to session 1, therapists met with clients to learn more about the client’s understanding of her/his worry and anxiety, to assess contextual factors that might affect the client’s symptoms and course of therapy (e.g., urgent financial, housing or family issues), to briefly explore the client’s cultural identity, to assess previous medication and therapy experiences, to address any potential obstacles to treatment, and to instill hope.

Acceptance Based Behavioral Therapy (ABBT: Roemer & Orsillo, 2009; Orsillo & Roemer, 2011)

As described above, ABBT focuses on modifying problematic relationships with one’s internal experiences, while decreasing experiential avoidance and behavioral constriction. Each session begins with a mindfulness exercise and a review of between session assignments, followed by the session specific content, and ending with the assignment of between session activities. A specific progression of mindfulness practices is used to help clients develop basic skills (e.g., observing breath during a sitting meditation) before moving toward the application of these skills in challenging contexts (e.g., observing painful thoughts and emotions during a conflict).

ABBT has two distinct phases of treatment. The first phase (roughly sessions 1–7) introduces clients to an acceptance-based behavioral model of anxiety, focusing on the function of anxiety and emotions more broadly, the ways that emotions can become intensified or “muddy”, the costs of trying to avoid or control internal experiences, and the potential benefit of taking an accepting, willing, and decentered stance and committing to making decisions based on values rather than avoiding anxiety. Clients are also introduced to mindfulness and gradually practice building mindfulness skills. Finally, a series of values-based writing exercises are used to help clients articulate what they value about relationships, work and school, and self-care and community engagement and eventually commit to taking mindful actions in these areas.

Sessions in the second phase (roughly sessions 8–16) focus on applying the mindfulness and acceptance skills developed in the first phase of therapy as the client pursues valued life directions each week. As obstacles arise (e.g., client reverts to control and avoidance strategies to cope with anxiety), the client and therapist return to concepts introduced earlier in treatment (e.g., attempts to control and avoid intensify anxiety, it is possible to experience anxiety and still pursue valued actions). In sessions fourteen through sixteen, clients review the changes they have made, consider strategies that were most effective, and plan for ways to maintain gains after termination.

Applied Relaxation (AR: Bernstein, Borkovec, & Hazlett-Stevens, 2000; Öst, 2007)

AR focuses on developing relaxation skills primarily through diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation (moving from 16 muscle-groups gradually to a rapid relaxation that can be applied in daily life); enhancing awareness of early signs of anxiety; and finally applying a brief relaxation exercise in response to early signs of anxiety. Our manual (reviewed by T.D. Borkovec) was derived from Bernstein et al. (2000) and Lars Öst’s treatment and expanded to 16 sessions to match ABBT. Each therapy session began with a diaphragmatic breathing or brief relaxation exercise, followed by a review of between session assignments, and ending with the assignment of between session activities. In the first half of AR (roughly sessions 1–8), the focus is on building relaxation skills and developing an awareness of client-specific early signs of anxiety. Clients began with a 16-muscle group PMR that was decreased to 8 and then 4 muscle groups once clients were able to achieve relaxation with the longer exercise. The second phase of therapy (roughly sessions 8–16) focuses on applying relaxation to early signs of anxiety both in session and between session. Clients are taught release-only, cue-controlled, differential, and rapid relaxation with an added focus on application skills. The last three sessions highlight relapse prevention and strategies for maintaining gains.

Therapists

Post-doctoral fellows (n = 3) or advanced doctoral students (n = 8), supervised by the study authors, saw roughly equal number of clients in each condition with an average of 3.64 (SD=3.79, range 1 to 11) ABBT and 3.73 (SD=3.23, range 1 to 11) AR clients. The initial therapists and the supervisors were trained by Dr. Tom Borkovec in Applied Relaxation and Dr. Zindel Segal in mindfulness therapies. Subsequent cohorts were trained by the supervisors.

Adherence and Competency

A total of 198 (ABBT = 96; AR = 102) sessions were rated for adherence to the respective protocols by doctoral students in clinical psychology. For each client, one session was randomly chosen from sessions 1–5, one from 6–11, and one from 12–16. For ABBT, an adherence checklist listed 9 allowed and 7 forbidden strategies (e.g. emphasizing the importance of changing cognitions, explicit statements about the goal being anxiety reduction). For AR, the checklist had 6 allowed and 10 forbidden strategies (e.g., clarification of emotional experience, suggestions of acceptance of one’s internal experiences, mentions of valued action). Each of the allowed elements were rated for the frequency/depth with which it was addressed in session from 0 (not at all) to 2 (addressed in detail) and for the skill with which it was addressed from 0 (poorly) to 2 (skillfully). In the ABBT condition, the allowed components were typically rated as being addressed in detail [means from 1.67 (SD=0.66) to 1.96 (SD=0.20)] and executed skillfully [means from 1.85 (SD=0.36) to 1.98 (SD=0.14)]. Only one session had a forbidden strategy (use of relaxation as a form of anxiety control). Twenty-five (26.0%) of these sessions were rated by a second rater with adequate reliability (κ=.73). Similarly, in the AR condition, the allowed components were typically rated as being addressed in detail [means from 1.89 (SD=0.37) to 1.96 (SD=0.20)] and executed skillfully [means from 1.91 (SD=0.29) to 1.97 (SD=0.17)]. No AR sessions had a forbidden strategy. Twenty-eight (27.4%) of these sessions were rated by a second rater with excellent reliability (κ=.91).

Additionally, 35 AR sessions were rated by Dr. Tom Borkovec for therapist competency with AR strategies. For each session, skills within the protocol for that session were rated on a four point Likert scale from 0 (poor) to 3 (excellent). The average score across skills was 2.38 (SD = 0.69) with 168 of the 187 ratings (89.8%) being good or excellent, 17 (9.1%) being acceptable, and 2 (1.1%) being poor.

Statistical Analyses

Data were examined for skewness, kurtosis, and outliers. Skewed scores [BDI-II, treatment credibility, and WAI-S (client)] were corrected with a square root transformation.

The primary analyses compared treatment differences over time in the intent-to-treat sample for ABBT and AR using Mixed-Effects Regression Models (MRM) in SPSS Version 18.0 (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006). Separate analyses were run for each of the outcome variables across the three time points (pre-treatment, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up). Models were run assuming random intercepts and slopes. In these hierarchical linear models, Level 1 models individual change over time and Level 2 models the between-subjects factors. Each MRM analysis examined the overall effect of change over time (Time), the difference between ABBT and AR (Condition), and the differences in changes over time by condition (Time X Condition). To assess maintenance of gains, the MRM analyses were repeated with just the post-treatment and follow-up time points. Per Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, and Burke (1996), Cohen’s d was calculated based on the between-groups t-test value: d = 2t/√(df).

Three indices of clinically significant change were examined, following the model of other RCTs for GAD (Newman et al., 2011; Borkovec & Costello, 1993): diagnostic status, responder status, and end state functioning. Diagnostic status was determined by CSR rating; those with a CSR of 3 or less were considered to no longer meet criteria for GAD. Responder status [following Borkovec and Costello (1993) guidelines] was defined as a reduction of symptoms of at least 20%. High endstate functioning was defined as falling within one standard deviation of the published norm on the outcome measures or receiving a GAD CSR of 3 or less (Ladouceur et al., 2000). Previous studies have used a cutoff of three out of four (Roemer et al., 2008) or three out of five (Newman et al., 2011) primary outcome measures to calculate responder status and high endstate functioning, thus we calculated both three out of four measures (GAD CSR, SIGH-A, PSWQ, and DASS-Stress) and three out of five measures (STAI-T added to the above list).

Missing Data

MRM models analyze data using maximum likelihood estimation to account for missing data, which assumes that data are “missing at random.” Therefore, following Hedeker & Gibbons (1997) recommendations, the effect of the pattern of missingness (completers vs. non-completers) on the rate of change by treatment condition was examined for each of the primary outcome variables. For each primary outcome variable, there were non-significant effects for Completer Status X Time X Treatment Group (p’s from .33 to .98). These results indicate that maximum likelihood estimation was an appropriate method for analyzing these data.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

There were no pre-treatment differences on any outcome variables: GAD severity [F(1,79) = 0.37, p=.54], SIGH-A [F(1,79) = 0.69, p=.41], PSWQ [F(1,77) = 2.86, p=.10], DASS-Stress [F(1,77) = 0.002, p=.96], STAI [F(1,77) = 0.10, p=.75], BDI-II [F(1,77) = 0.31, p=.58], quality of life [F(1,77) = 2.58, p=.11], number of additional diagnosis [F(1,79) = 0.92, p=.34]. There were also no significant differences in the number of sessions completed for individuals in ABBT compared to AR [ABBT - 12.80 (SD = 5.50); AR - 13.15 (SD = 5.54); F(1,79)=0.08, p=.78]. Over the course of therapy, 2 individuals began a medication for anxiety or depression (both ABBT); 2 began then ended a medication within 5 weeks (1 ABBT; 1 AR); 3 took 1–2 doses of a benzodiazepine over the entire course of therapy (2 ABBT, 1 AR); 3 decreased or went off of a medication (2 ABBT; 1 AR); and 6 (ABBT = 3; AR = 3) received additional therapy (3 couples/family therapy; 3 check-in with previous therapists; 1 grief counseling)4. There were no significant patterns of difference across treatments for whether or not clients were on anxiety or depression medications [post-treatment - χ2(1) = 0.91, p = .34; 6-month follow-up - χ2(1) = 0.04, p = .85] or received additional psychotherapy since the previous assessment [post-treatment - χ2(1) = 0.002, p = .97; 6-month follow-up - χ2(1) = 1.78, p = .18].

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The means and standard deviations of all outcome measures at each time point are presented in Table 2 and Table 3 presents the results of the MRM models. The MRM model for CSR showed a significant (large) effect for Time but non-significant, small effects for Condition and for the Condition X Time effect indicating that clients’ clinician rated severity of GAD diagnosis significantly decreased across treatment and follow-up and that this change was not different across the two treatments. Similarly, for SIGH-A, there was a significant, large effect for Time but non-significant, small effects for Condition and for the Condition X Time effect. A similar pattern of results emerged on the self-reported primary outcome measures, indicating that clients significantly improved over time on self-reports of excessive worry (PSWQ), tension and GAD symptoms (DASS-Stress), and anxiety symptoms (STAI), while no differences emerged in these changes between treatments (with small effect sizes). MRM models run for the secondary outcomes yielded consistent results, with significant (large) effects of Time for each outcome, but non-significant, small effects for both Condition and Condition X Time. Together these results indicate that clients’ self-reported depressive symptoms and clinician-rated number of additional diagnoses significantly decreased and self-reported quality of life increased over time. However, there were no significant differences in these rates of change across treatments.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations (untransformed) of outcome measures at each time point

| Pretreatment M (SD) (N = 81) | Posttreatment M(SD) (N = 63) | 6 month FU M (SD) (N = 55) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||

| GAD CSR | |||

| ABBT | 5.53 (0.55) | 3.03 (1.38) | 2.88 (1.59) |

| AR | 5.44 (0.71) | 2.70 (1.57) | 2.77 (1.59) |

| SIGH-A | |||

| ABBT | 19.31 (6.55) | 10.98 (7.06) | 9.54 (7.53) |

| AR | 20.54 (6.79) | 11.48 (6.20) | 10.75 (6.93) |

| PSWQ | |||

| ABBT | 67.67 (8.10) | 51.03 (8.46) | 50.37 (11.34) |

| AR | 70.41 (6.22) | 52.28 (10.69) | 52.27 (10.57) |

| DASS-Stress | |||

| ABBT | 24.49 (8.73) | 13.37 (6.44) | 12.84 (7.68) |

| AR | 24.58 (7.64) | 12.00 (8.43) | 11.53 (7.75) |

| STAI | |||

| ABBT | 53.94 (9.81) | 43.46 (10.39) | 42.88 (10.94) |

| AR | 53.30 (7.87) | 43.48 (12.07) | 40.72 (10.44) |

| Secondary Outcome | |||

| BDI-II | |||

| ABBT | 19.33 (11.10) | 9.54 (10.76) | 8.93 (11.91) |

| AR | 17.92 (10.60) | 7.85 (8.51) | 7.47 (8.73) |

| QOLI | |||

| ABBT | 0.24 (2.14) | 1.56 (1.78) | 1.41 (1.80) |

| AR | 0.86 (1.18) | 1.87 (1.60) | 1.92 (1.41) |

| Number of Additional Diagnoses | |||

| ABBT | 0.95 (0.98) | 0.55 (0.92) | 0.48 (0.92) |

| AR | 1.15 (0.85) | 0.52 (0.71) | 0.37 (0.56) |

| Process Measures | |||

| Treatment Credibility | |||

| ABBT | 29.00 (5.12) | -- | -- |

| AR | 28.84 (4.89) | -- | -- |

| WAI – client | |||

| ABBT | 70.52 (10.44) | -- | -- |

| AR | 73.15 (7.41) | -- | -- |

| WAI - therapist | |||

| ABBT | 64.31 (8.13) | -- | -- |

| AR | 66.14 (7.36) | -- | -- |

| To what extent do you feel that this treatment was a good match for you? | |||

| ABBT | -- | 7.39 (1.41) | -- |

| AR | -- | 7.41 (1.66) | -- |

Note. ABBT = acceptance-based behavior therapy; AR = applied relaxation; FU = follow-up; CSR = clinician severity rating; SIGH-A; structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, Stress scale; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory – II; QOLI = Quality of Life Inventory; WAI = Working Alliance Inventory.

Table 3.

Results of the mixed effects regression models examining change across treatment and follow-up

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||||||

| GAD CSR | |||||||

| Time | −1.41 | 0.18 | −7.92 | 116.14 | <.001 | −1.76, −1.05 | 1.47 |

| Condition | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 139.80 | .47 | −0.30, 0.64 | 0.12 |

| Condition X Time | <0.01 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 115.23 | .99 | −0.51, 0.52 | 0.002 |

| SIGH-A | |||||||

| Time | −5.03 | 0.70 | −7.14 | 83.00 | <.001 | −6.44, −3.63 | 1.57 |

| Condition | −0.92 | 1.41 | −0.65 | 110.66 | .52 | −3.71, 1.88 | 0.12 |

| Condition X Time | −0.01 | 1.16 | −0.01 | 69.46 | .99 | −2.32, 2.30 | 0.002 |

| PSWQ | |||||||

| Time | −9.49 | 1.30 | −7.33 | 116.40 | <.001 | −12.06, −6.93 | 1.36 |

| Condition | −2.17 | 1.74 | −1.24 | 135.62 | .22 | −5.62, 1.28 | 0.21 |

| Condition X Time | 0.12 | 1.88 | 0.06 | 115.17 | .95 | −3.61, 3.85 | 0.01 |

| DASS-Stress | |||||||

| Time | −6.84 | 0.92 | −7.46 | 85.94 | <.001 | −8.67, −5.02 | 1.61 |

| Condition | 0.26 | 1.70 | −1.24 | 111.32 | .88 | −3.12, 3.64 | 0.24 |

| Condition X Time | 0.82 | 1.34 | 0.61 | 86.23 | .54 | −1.85, 3.48 | 0.13 |

| STAI-T | |||||||

| Time | −5.87 | 0.91 | −6.45 | 67.71 | <.001 | −7.68, −4.05 | 1.57 |

| Condition | 0.83 | 2.06 | 0.40 | 96.66 | .69 | −3.27, 4.93 | 0.08 |

| Condition X Time | −0.01 | 1.34 | −0.01 | 68.77 | .99 | −2.67, 2.66 | 0.002 |

| Secondary Outcome | |||||||

| BDI-II | |||||||

| Time | −0.87 | 0.15 | −5.64 | 66.92 | <.001 | −1.18, −0.56 | 1.38 |

| Condition | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.68 | 92.27 | .50 | −0.41, 0.84 | 0.14 |

| Condition X Time | <0.01 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 67.76 | .99 | −0.45, 0.46 | 0.004 |

| QOLI | |||||||

| Time | 0.50 | 0.12 | 4.07 | 120.24 | <.001 | 0.26, 0.75 | 0.74 |

| Condition | −0.59 | 0.37 | −1.57 | 103.24 | .12 | −1.33, 0.16 | 0.31 |

| Condition X Time | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 122.50 | .55 | −0.26, 0.47 | 0.11 |

| Number of Additional Diagnoses | |||||||

| Time | −0.38 | 0.07 | −5.16 | 130.85 | <.001 | −0.52, −0.23 | 0.90 |

| Condition | −0.19 | 0.18 | −1.03 | 127.26 | .30 | −0.54, 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Condition X Time | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1.38 | 132.63 | .17 | −0.06, 0.36 | 0.24 |

Note. CSR = clinician severity rating; SIGH-A; structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, Stress scale; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory – II; QOLI = Quality of Life Inventory; WAI = Working Alliance Inventory.

Process Measures

As shown in Table 2, on average clients in both ABBT and AR rated their respective treatments as highly credible (28.92 out of 36) and ratings of credibility did not differ across treatments [F(1, 74) = 0.06, p = .80, d = 0.06]. At the end of session 4, both clients (71.87 out of 84) and therapists (65.27 out of 84) reported strong working alliances. There were no significant differences between ABBT and AR in terms of client [F(1, 64) = 0.80, p = .38, d = 0.22] or therapist [F(1, 65) = 0.94, p = .34, d = 0.24] ratings of the working alliance.

At the end of treatment, clients rated both treatments to be a good match for their needs (means of 7.41 and 7.39 for ABBT and AR, respectively) on a 9-point Likert scale with no significant differences between treatments [F(1, 62) = 0.003, p = .96, d = 0.01].

Maintenance of Gains

To specifically examine maintenance of gains from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up, the above MRM models were repeated with only these two time points in the models. As shown in Table 4, there were no significant Time, Condition, or Time X Condition effects and all effect sizes were small, indicating comparable maintenance of gains across follow-up.

Table 4.

Results of the mixed effects regression models examining maintenance of gains from post-treatment to 6-month follow-up

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | |||||||

| GAD CSR | |||||||

| Time | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 140.66 | .58 | −0.36, 0.63 | 0.09 |

| Condition | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.93 | 106.45 | .37 | −0.56, 1.55 | 0.18 |

| Condition X Time | −0.16 | 0.37 | −0.42 | 143.53 | .67 | −0.89, 0.57 | −0.07 |

| SIGH-A | |||||||

| Time | −0.23 | 1.08 | −0.21 | 120.32 | .83 | −2.37, 1.90 | −0.04 |

| Condition | 0.41 | 2.25 | 0.18 | 85.00 | .86 | −4.06, 4.88 | 0.04 |

| Condition X Time | −0.91 | 1.60 | −0.57 | 121.59 | .57 | −4.08, 2.26 | −0.10 |

| PSWQ | |||||||

| Time | 0.97 | 1.60 | 0.60 | 87.85 | .55 | −2.22, 4.16 | 0.13 |

| Condition | 0.37 | 3.31 | 0.11 | 59.80 | .91 | −6.24, 6.99 | 0.03 |

| Condition X Time | −1.52 | 2.37 | −0.64 | 88.32 | .52 | −6.22, 3.19 | −0.14 |

| DASS-Stress | |||||||

| Time | −0.15 | 1.22 | −0.12 | 138.02 | .90 | −2.56, 2.26 | −0.02 |

| Condition | 1.14 | 2.56 | 0.44 | 100.64 | .66 | −3.94, 6.21 | 0.09 |

| Condition X Time | 0.23 | 1.80 | 0.13 | 134.00 | .90 | −3.34, 3.80 | 0.02 |

| STAI-T | |||||||

| Time | −1.36 | 1.74 | −0.78 | 101.84 | .44 | −4.81, 2.08 | −0.15 |

| Condition | −1.82 | 3.57 | −0.51 | 67.43 | .61 | −8.95, 5.30 | −0.12 |

| Condition X Time | 1.80 | 2.60 | 0.69 | 102.76 | .49 | −3.37, 6.96 | 0.14 |

| Secondary Outcome | |||||||

| BDI-II | |||||||

| Time | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.42 | 112.21 | .68 | −0.42, 0.65 | 0.08 |

| Condition | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 74.84 | .46 | −0.71, 1.52 | 0.17 |

| Condition X Time | −0.07 | 0.40 | −0.18 | 113.08 | .86 | −0.88, 0.73 | −0.03 |

| QOLI | |||||||

| Time | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 125.38 | .92 | −0.49, 0.54 | 0.02 |

| Condition | −0.17 | 0.55 | −0.31 | 88.50 | .76 | −1.26, 0.92 | −0.06 |

| Condition X Time | −0.14 | 0.39 | −0.35 | 127.65 | .72 | −0.92, 0.64 | −0.06 |

| Number of Additional Diagnoses | |||||||

| Time | −0.12 | 0.13 | −0.90 | 124.00 | .37 | −0.37, 0.14 | −0.16 |

| Condition | −0.09 | 0.28 | −0.31 | 94.39 | .75 | −0.63, 0.46 | −0.06 |

| Condition X Time | 0.12 | .19 | 0.63 | 128.26 | .53 | −0.26, 0.50 | 0.11 |

Note. CSR = clinician severity rating; SIGH-A; structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, Stress scale; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory – II; QOLI = Quality of Life Inventory; WAI = Working Alliance Inventory.

Clinical Significance

Diagnostic change, responder status, and high end-state functioning at post-treatment and at 6-month follow-up are reported in Table 5. At post-treatment 63.3–80.0% of clients in ABBT and 60.6–78.8% in AR exhibited clinically significant change. Similar rates were found for ABBT, 66.7–80.0%, and AR, 60.6–78.8%, at follow-up. There were no significant differences between conditions at either time point, with small effect sizes (d’s from 0.01 to 0.28).

Table 5.

Percentage of Treatment Completersa (n=63) Meeting Criteria for Diagnostic Change, Responder Status, and High End-State Functioning at Post-treatment and 6-Month Follow-Up.

| Diagnostic Change | X2 | p | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABBT | AR | ||||

| Post-tx | 80.0% (24/30) | 69.7% (23/33) | 0.88 | .35 | 0.24 |

| 6MFU | 72.0% (18/25) | 70.0% (21/30) | 0.03 | .87 | 0.05 |

| 66.7% (20/30) | 73.3% (22/33) | 0.00 | .99 | 0.01 | |

| Responder Status (3 of 4) | |||||

| Post-tx | 70.0% (21/30) | 78.8% (26/33) | 0.64 | .42 | 0.20 |

| 6MFU | 76.0% (19/25) | 71.4% (20/28) | 0.14 | .71 | 0.10 |

| 70.0% (21/30) | 72.7% (24/33) | 0.06 | .81 | 0.06 | |

| Responder Status (3 of 5) | |||||

| Post-tx | 73.3% (22/30) | 78.8% (26/33) | 0.26 | .61 | 0.13 |

| 6MFU | 76.0% (19/25) | 78.6% (22/28) | 0.05 | .82 | 0.06 |

| 73.3% (22/30) | 78.8% (26/33) | 0.26 | .61 | 0.13 | |

| High End-State (3 of 4) | |||||

| Post-tx | 63.3% (19/30) | 60.6% (20/33) | 0.05 | .82 | 0.06 |

| 6MFU | 80.0% (20/25) | 67.8% (19/28) | 1.00 | .32 | 0.28 |

| 73.3% (22/30) | 60.6% (20/33) | 1.14 | .28 | 0.27 | |

| High End-State (3 of 5) | |||||

| Post-tx | 73.3% (22/30) | 72.7% (24/33) | 0.00 | .96 | 0.01 |

| 6MFU | 80.0% (20/25) | 75.0% (21/28) | 0.19 | .66 | 0.12 |

| 76.7% (23/30) | 66.7% (22/33) | 0.77 | .38 | 0.22 | |

Note.

Treatment completers are those who completed at least 13 of the 16 sessions. Italic type indicates the last available values carried forward for the calculations for participants who were designated treatment completers, but did not attend the 6-month follow-up assessment. Responder status and end-state functioning was calculated two ways, following: Roemer et al. (2008; response on 3 of 4 measures, CSR, SIGH-A, PSWQ, and DASS-Stress) and Newman et al. (2011; responses on 3 of 5 measures, CSR, SIGH-A, PSWQ, DASS-Stress, and STAI-T). ABBT = acceptance-based behavior therapy; AR = applied relaxation; 6MFU = 6-month post-treatment follow-up assessment.

Discussion

Both an Acceptance Based Behavior Therapy and Applied Relaxation led to statistically and clinically significant change across treatment and short-term follow-up. Overall, there were large effects for change over time in all of the primary outcome measures for clients receiving either treatment. While there are many limits inherent in comparing outcomes across studies (i.e. no randomization, different populations, research/therapy team effects, measurement differences) and studies of therapy for GAD have traditionally calculated clinically significant change differently, it appears as though the percentage of clients in ABBT (and AR) who experienced clinically meaningful change was comparable to most other reported treatment effects for clients with GAD. For example, the current study found that end state functioning for ABBT was similar to Ladouceur et al. (2000) and more than 5 percentage points higher than any condition in Newman et al. (2011) and Borkovec et al. (2002) at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up. ABBT’s rate of diagnostic change at post-treatment was equal to or greater than remission rates reported in Dugas et al. (2010), Wells, et al. (2010), and Arch et al. (2012). Of note, the recovery rate in Wells is based only on the PSWQ and Arch et al is based on a small sample. However, Dugas and colleagues reported a slightly higher rate of responders at 6-month follow-up (76% vs. 72%). While it is difficult to make comparisons across measures, statistical analyses, and samples that may differ in pretreatment characteristics, compared to other GAD RCTs our pre to post treatment Cohen’s d effect sizes of 1.36 to 1.61 are slightly smaller than the Cohen’s d of 1.86 for a symptom severity composite variable (Newman et al., 2011) and in between the effect sizes for Metacognitive Therapy (PSWQ d=3.41) and Applied Relaxation (PSWQ d=0.95; Wells et al., 2010)5. However, future studies are needed to more directly compare these treatments.

To specifically examine maintenance of gains over a 6-month follow-up period, we examined change from post to follow-up, as well as the percentage of individuals meeting criteria for clinically significant change. As some clients were lost to follow-up, we examined the percentage of individuals making clinically significant changes for only the clients who completed the follow-up assessment as well as while carrying forward post-treatment scores. Overall, clients in ABBT and AR maintained gains across all outcome measures.

Clients reported comparable (high) levels of treatment credibility at the beginning of treatment, as well as comparable (high) levels of match in treatments at the end of treatment. Clients and therapists in both conditions also reported comparably strong working alliances. These findings indicate acceptability of both treatments for clients with GAD.

While our hypothesis that ABBT would outperform our active competitor, AR, was not supported, this is likely partially due to the particularly strong efficacy of AR in the current study. AR has long been considered one of the leading treatments of GAD and we designed our AR protocol to achieve maximal potency. We combined all elements from Öst (2007) and Bernstein et al, (2000); whereas some trials have only used the relaxation components of AR, we dedicated significant in and out of session time to noticing early cues of anxiety and applying an alternate response. We also extended the typical length of AR from 12 to 16 sessions and our therapists were rated as highly competent by one of the developers of AR (T. D. Borkovec). As a result, our AR outcomes were notably stronger than those found in previous trials. For instance, Borkovec and Costello (1993) found 44% of individuals receiving AR met criteria for high end state functioning at post-treatment, while Wells and colleagues (2010) reported only 20% recovered and 10% improved at post-treatment. Further research is needed that examines the optimal number of sessions for each of these treatments.

Although adherence ratings indicate that elements of ABBT (i.e., mindfulness, acceptance, and valued action) were not explicitly introduced in AR, the use of the same therapists across both conditions may have inadvertently introduced some nonspecific acceptance-based effects into the AR condition. It is also quite possible that AR and ABBT share common mechanisms of change. For example, AR may promote mindfulness, acceptance, and decentering, all theorized to be key components underlying ABBT (Hayes-Skelton, Usmani, Lee, Roemer, & Orsillo, 2012) and increases in self-reported decentering appears to lead to symptom change in both ABBT and AR (Hayes-Skelton, Roemer, & Orsillo, 2011, November). More research is needed to examine the similar and divergent mechanisms of change underlying both of these treatments.

Contrary to hypotheses, ABBT did not lead to significantly greater decreases in depression and comorbid conditions and increases in quality of life than AR. We predicted these differences because ABBT explicitly targets mechanisms thought to underlie a range of disorders (Hayes et al., 1996). As expected, ABBT did have a significant impact on these outcomes, with large effect sizes. Unexpectedly, AR demonstrated a comparable impact. Extensive focus on reducing habits of anxious responding may in turn help clients naturally engage more in their lives even without an explicit focus on behavioral action. More research is needed to explore the mechanisms that underlie these effects within AR.

As with all studies, this study had a number of limitations. To control for therapist effects, all therapists administered both treatments. This raises the possibility of treatment diffusion or differences in therapist’s allegiance. However, a large proportion of clients were seen by therapists with a stronger background in traditional CBT and adherence ratings showed that therapists were adherent to their respective treatment conditions. Further, although the investigators were developers of ABBT, AR competence was rated very highly by one of the developers of AR. An additional limitation is that all of our therapists were relatively inexperienced (graduate students and post-doctoral fellows), which may have reduced the efficacy of interventions. Further, as with most RCTs, this study favored internal over external validity. For example, there was a fixed treatment length and treatment followed a protocol that did not allow for the possibility of adapting the therapy with treatment elements from other approaches. Because of these limitations it is unclear how ABBT would perform in routine clinical practice. Similarly, this sample was predominantly White, limiting the conclusions that can be made about the efficacy of ABBT with more diverse populations. Based on qualitative interviews of ABBT clients who ascribed to a nondominant identity (race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, or socioeconomic status), clients found ABBT fit well culturally and particularly appreciated the emphasis on valued living and the flexibility of the therapy and the therapists (Fuchs et al., 2012, April). However, more research is needed to systematically assess the portability of this therapy to other settings and populations. Similarly, the current study also did not address the question of differential dissemination. For example, AR is simple, which makes it seem like a good candidate for dissemination. However, it is more inflexible and demanding in terms of client time required and so may not be as effective with clients who are not receiving free treatment; while this ABBT is flexible and adapts to client’s circumstances, which was mentioned as a strength of ABBT by our clients (Fuchs et al., 2012, April). Additionally, at this point, there is little information regarding moderators and predictors of outcome in either ABBT or AR. More evidence of moderators and differential predictors would also help address these questions of differential dissemination.

To address these limitations and further understand the dissemination and usefulness of ABBT across contexts, future studies are needed to explore adaptations that will make ABBT more efficient for other settings, for example as a workshop intervention (e.g., Blevins, Roca, & Spencer, 2011) or in primary care settings, as well as responsive to contextual and cultural factors (Fuchs, Lee, Roemer, & Orsillo, in press; Rucker Sobscak & West, in press). In addition to studying the application of ABBT to naturalistic settings, studies need to examine the portability and dissemination of this treatment to clinical practice. These dissemination efforts will be aided by a better understanding of common and unique mechanisms of change across these two treatments, as well differential predictors of treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. MH074589 awarded to the second and third authors and MH085060 awarded to the first author. The authors thank the large team that made this project possible. Tom Borkovec and Zindel Segal provided training to therapists. Tom Borkovec also completed competency ratings of AR therapists. Tim Brown managed the assessment team. Therapists included: Stephanie Czech Berube, Shannon Erisman, Cara Fuchs, Kara Lustig, Jonathan Lee, Heather Murray, Kathleen Sullivan Kalill Michael Treanor, Aisha Usmani, Lindsey West, as well as the first author. Assessors included: Michael Moore, Aaron Kaiser, Cathryn Freid, Ovsanna Leyfer, Joseph Meyer, Anthony Rosellini, and Cassidy Gutner. Additionally, we would like to thank the following for their help with data management and adherence ratings: Heidi Barrett Model, Stephanie Czech Berube, Shannon Erisman, Liz Eustis, Cara Fuchs, Jessica Graham, Aviva Katz, Sarah Krill, Lucas Morgan, Dan Paulus, Estie Reidler, Michael Treanor, and Lindsey West, as well as numerous UMB undergraduate students. Finally, we would like to thank the clients. This work would not be possible without their openness, courage, and willingness.

Footnotes

This specific ABBT is thus part of a larger class of acceptance-based behavioral therapies, developed to target GAD and related symptoms, similar to a particular CBT protocol for a target condition being part of a larger class of cognitive-behavioral therapies (Roemer & Orsillo, 2009).

Treatment completers were those clients who completed at least 13 of the 16 sessions. This includes five clients who completed 14–15 sessions instead of the full 16. Four of these five clients had planned early endings because either the client (n=2) or the therapist (n=2) was moving the area. The reason the fifth client ended early was unknown. Additionally, one client in AR felt that she had improved by session 2 and agreed to an abbreviated 8 week course of treatment. The reasons that individuals dropped out of therapy before session 13 are included in Figure 1.

As described in Brown et al. (2001) all assessors underwent extensive training before administering the ADIS. Initial training included reading the manual, observing interviewers, and administering interviews in collaboration with a certified interviewer. Then to be certified, assessors needed to match a senior interviewer’s diagnoses on three of five consecutive interviews. A match was defined as agreement on the principal diagnosis and agreement within 1 point on the CSR as well as the identification of all additional clinically significant disorders.

Therapy check-ins and unrelated therapy were allowed by protocol; starting and stopping medication and 1 – 2 uses of benzodiazepines are unlikely to affect outcomes, and reducing or ceasing medication are likely to underestimate effects of treatments.

Dugas et al. (2010) did not report Cohen’s d effect sizes.

Contributor Information

Sarah A. Hayes-Skelton, University of Massachusetts Boston

Lizabeth Roemer, University of Massachusetts Boston.

Susan M. Orsillo, Suffolk University

References

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:176–181. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Eifert GH, Davies C, Vilardaga JCP, Rose RD, Craske MG. Randomized Clinical Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Versus Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Mixed Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012 May 7; doi: 10.1037/a0028310. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg M, van IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(1):1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard PJ, Teasdale JD. Interacting cognitive subsystems: A systemic approach to cognitive-affective interaction and change. Cognition and Emotion. 1991;5:1–39. doi: 10.1080/02699939108411021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory manual. 2. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Behar E, DiMarco ID, Hekler EB, Mohlman J, Staples AM. Current theoretical models of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD): Conceptual review and treatment implications. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:1011–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DA, Borkovec TD, Hazlett-Stevens H. New directions in progressive relaxation training: A guidebook for helping professionals. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins D, Roca J, Spencer T. Life Guard: Evaluation of an ACT-based workshop to facilitate reintegration of OIF/OEF veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;42:32–39. doi: 10.1037/a0022321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Alcaine OM, Behar E. Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:611–619. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Newman MG, Pincus AL, Lytle R. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the role of interpersonal problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:288–298. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Nau SD. Credibility of analogue therapy rationales. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1972;3:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(72)90045-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec TD, Ruscio AM. Psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Machan JT, Dyck I, Keller MB. Infrequency of ‘pure’ GAD: Impact of psychiatric comorbidity on clinical course. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;14(4):219–225. doi: 10.1002/da.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Covin R, Ouimet AJ, Seeds PM, Dozois DJA. A meta-analysis of CBT for pathological worry among clients with GAD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craigie MA, Rees CS, Marsh A, Nathan P. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary evaluation. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:553–568. doi: 10.1017/S135246580800458X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. Albany NY: Graywind Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, Turcotte J, Gaudet A, Ladouceur R, Gervais NJ. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap WP, Cortina WP, Vaslow JB, Burke MJ. Meta-analysis of experiments with matched groups or repeated measures designs. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:170–177. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Ferrando S, Findler M, Stowell C, Smart C, Haglin D. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22:716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MB, Cornwell J, Villanueva M, Retzlaff PJ. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: A measure of life satisfaction of use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:92–101. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C, Lee JK, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Clinical considerations in using acceptance- and mindfulness-based treatments with diverse populations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.12.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C, West LM, Graham JR, Hayes-Skelton SA, Orsillo SM, Roemer L. Exploring the acceptability of mindfulness-based treatment among individuals from non-dominant cultural backgrounds. Examining mindfulness and anxiety across diverse methods and contexts; Symposium to be presented at the annual meeting of the Anxiety Disorders Association of America; Arlington, VA. 2012. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Orsillo SM, Roemer L. Changes in proposed mechanisms of action during an acceptance-based behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Skelton SA, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Decentering as a common mechanism across two therapies for generalized anxiety disorder. In: Moscovitch DA, Huppert JD chairs, editors. Early changes in emotion regulation processes during CBT for emotional disorders: Psychological markers of treatment success; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy; Toronto, ON. 2011. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Skelton SA, Usmani A, Lee J, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. A fresh look at potential mechanisms of change in Applied Relaxation: A case series. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012;19:451–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal Data Analysis. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman DL, Dukes EM, Wittchen H. Human and economic burden of generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(1):72–90. doi: 10.1002/da.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur R, Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Léger E, Gagnon F, Thibodeau N. Efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a controlled clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:957–964. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Orsillo SM, Roemer L, Allen LB. Distress and avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: Exploring the relationships with intolerance of uncertainty and worry. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2010;39:126–136. doi: 10.1080/16506070902966918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Llera SJ, Newman MG. Effects of worry on physiological and subjective reactivity to emotional stimuli in generalized anxiety disorder and nonanxious control participants. Emotion. 2010;10:640–650. doi: 10.1037/a0019351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney: The Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1281–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson SE, Lee JK, Orsillo SM, Roemer L. The role of values-consistent behavior in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:358–366. doi: 10.1002/da.20793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and the National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: NICE clinical guideline 113. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; London, England: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Castonguay LG, Borkovec TD, Fisher AJ, Boswell JF, Szkodny LE, Nordberg SS. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder with integrated techniques from emotion-focused and interpersonal therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:171–181. doi: 10.1037/a0022489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsillo SM, Roemer L. The mindful way through anxiety: Break free from chronic worry and reclaim your life. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Öst L-G. Applied relaxation: Manual for a behavioral coping technique. 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Expanding our conceptualization of and treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: Integrating mindfulness/acceptance-based approaches with existing cognitive-behavioral models (Featured article) Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:54–68. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/9.1.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. An open trial of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Mindfulness- and acceptance-based behavioral therapies in practice. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM. An acceptance-based behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical handbook for psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. 5. New York: Guilford publications; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Orsillo SM, Salters-Pedneault K. Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:1083–1089. doi: 10.1037/a0012720;10.1037/a0012720.supp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker Sobczak LS, West L. Clinical considerations in using mindfulness- and acceptance-based approaches with diverse populations: Addressing challenges in service-delivery in diverse community settings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice in press. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shear M, Vander Bilt J, Rucci P, Endicott J, Lydiard B, Otto MW, Frank DM. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A) Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:166–178. doi: 10.1002/da.1033.abs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siev J, Chambless DL. Specificity of treatment effects: Cognitive therapy and relaxation for generalized anxiety and panic disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:513–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y Self-evaluation Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tracey TJ, Kokotovic AM. Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1:207–210. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.1.3.207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Treanor M, Erisman SM, Salters-Pedneault K, Roemer L, Orsillo SM. Acceptance-based behavioral therapy for GAD: Effects on outcomes from three theoretical models. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28:127–137. doi: 10.1002/da.20766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters AM, Craske MG. Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Antony MM, Ledley DR, Heimberg RG, editors. Improving outcomes and preventing relapse in cognitive-behavorial therapy. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 77–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Carter K. Preliminary tests of a cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1999;37:585–594. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells A, Welford M, King P, Papageorgiou C, Wisely J, Mendel E. A pilot randomized trial of metacognitive therapy vs applied relaxation in the treatment of adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(5):429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell JL, Liu L, Patterson TL, Afari N, Ayers CR, Thorp SR, Stoddard JA, Ruberg J, Kraft A, Sorrell JT, Petkus AJ. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for generalized anxiety disorder in older adults: A preliminary report. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]