Abstract

Cyclic-AMP response-element binding protein (CREB) is a stimulus-activated transcription factor. Its transcription activity requires its binding with CREB-binding protein (CBP) after CREB is phosphorylated at Ser133. The domains involved for CREB-CBP interaction are kinase-inducible domain (KID) from CREB and KID-interacting domain (KIX) from CBP. Recent studies suggest that CREB is an attractive target for novel cancer therapeutics. To identify novel chemotypes as inhibitors of KIX-KID interaction, we screened the NCI-diversity set of compounds using a split renilla luciferase assay and identified 2-[(7-nitrobenzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazol-4-yl)thio]pyridine 1-oxide (compound 1) was identified as a potent inhibitor of KIX-KID interaction. However, compound 1 was not particularly selective against CREB-mediated gene transcription in living HEK 293T cells. Further structure-activity relationship studies identified 4-aniline substituted nitrobenzofurazans with improved selectivity.

Keywords: CREB, CBP, cancer, inhibitor, screening, selectivity, structure-activity relationships

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response-element (CRE) binding protein (CREB) is a nuclear transcription factor belonging to a family of basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-containing transcription factors.1,2 As a stimulus-activated transcription factor, CREB is activated by a variety of extracellular signals including growth factors through protein serine/threonine kinases.2 A key residue in CREB that is phosphorylated in this signaling cascade is Ser133 located in the kinase inducible domain (KID) and the phosphorylated CREB is referred to p-CREB.3 Once phosphorylated, CREB binds mammalian transcription co-activators and histone acetyl transferases, CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its closely related paralog p300, through their KIX (KID-interacting) domain. This complex will recruit additional transcription machinery to initiate CREB-mediated gene transcription activation.4

A variety of protein serine/threonine kinases including protein kinase A (PKA), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), protein kinase B (PKB/Akt), ribosome S6 kinase (p90RSK) can activate CREB through phosphorylation at Ser133.5 On the other hand, CREB's transcription activity can be attenuated by protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate Ser133. The phosphatases that are known to remove this phosphate include protein phosphatase 1 (PP1),6 protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A)7 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN).8 Since most of the CREB kinases are often aberrantly activated while the CREB phosphatases are often inactivated in cancer cells, CREB has been shown to be overexpressed and/or overactivated in both solid and liquid tumor tissues.9 As such, CREB has been proposed as a novel target for cancer therapeutics discovery.9 Various strategies have been exploited to discover potential small molecule binders for CREB or CBP.9-15 Among the ligands discovered to date, naphthol AS-E and its derivatives are the only ones that are known to inhibit CREB-mediated gene transcription in living cells.10,14,16,17 Therefore, additional small molecule inhibitors, preferably with different chemotypes, are in great need to further elucidate the roles of CREB in maintaining tumor phenotype.

A critical event for the activation of CREB-dependent gene transcription is the formation of KID-KIX complex between CREB and CBP.4 We recently described a split renilla luciferase (RLuc) assay to monitor KIX-KID interaction.10 In this assay, RLuc was split into N-terminal half (RLucN) and C-terminal half (RLucC). KID was fused with RLucN while KIX was fused with RLucC to give fusions KID-RLucN and RLucC-KIX, respectively On their own, these polypeptides did not present RLuc activity. However, the RLuc activity was specifically restored when KID-RLucN and RLucC-KIX were combined together.10 Herein we present our studies on the identification of substituted benzofurazans as small molecule inhibitors of KIX-KID interaction and CREB-mediated gene transcription.

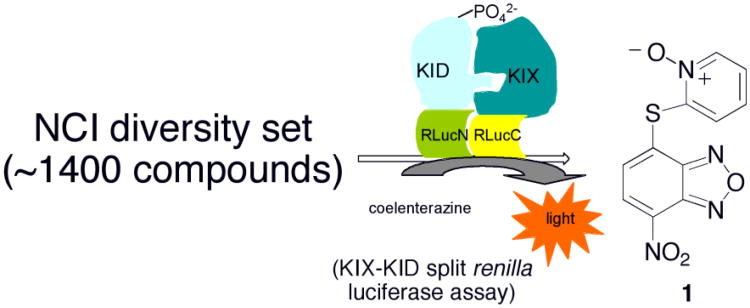

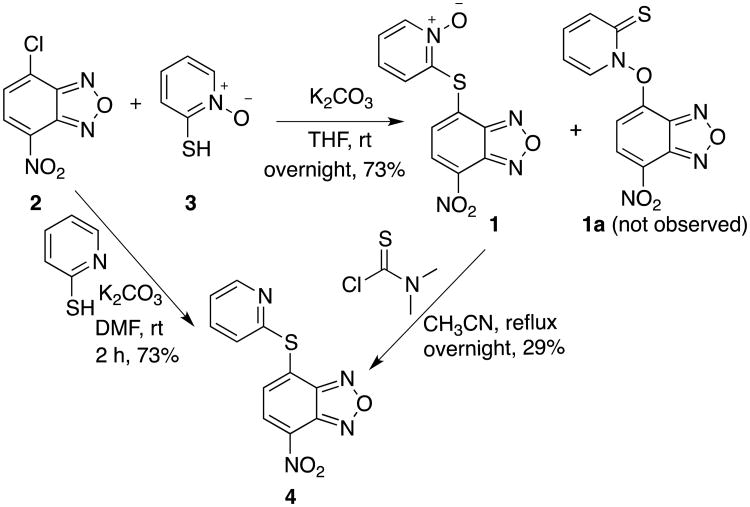

To identify novel chemotype(s) as potential inhibitors of KIX-KID interaction, the split RLuc assay10 was employed to screen the National Cancer Institute (NCI)'s diversity set of ∼1,400 compounds (Figure 1), whose structures cover significant variations.18,19 The compounds were initially screened at 10 μM concentration and 2-[(7-nitrobenzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazol-4-yl)thio]pyridine 1-oxide (compound 1, Figure 1) was consistently shown to efficaciously inhibit KIX-KID interaction. Therefore, this compound was independently synthesized as shown in Scheme 1 for further characterization. SNAr displacement of chloride from 4-chloro-7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD-Cl, 2) by 2-pyridinethiol 1-oxide (3) in the presence of K2CO3 gave compound 1 in 73% yield.20 The desired S-arylation in 1, instead of the alternative O-arylation product 1a,21 was confirmed by its conversion to deoxygenated compound 4 by the action of dimethylthiocarbamoyl chloride (DMTCC) (Scheme 1).22 Compound 4 could also be obtained directly from coupling NBD-Cl (2) with 2-pyridinethiol in the presence of K2CO3 in 73% yield (Scheme 1).

Figure 1.

Identification of compound 1 as an inhibitor of KIX-KID interaction from screening of the NCI diversity set by KIX-KID split renilla luciferase assay.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1 and 4.

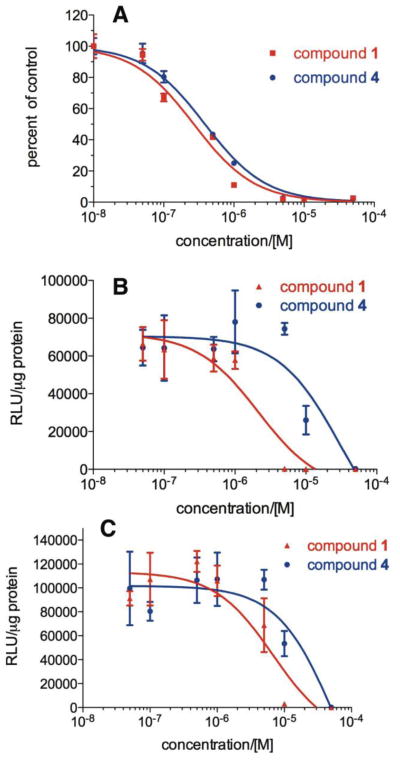

Consistent with the screening results, synthetic compound 1 dose-dependently inhibited KIX-KID interaction as evaluated by the split RLuc assay with an IC50 of 0.36 μM (Figure 2A and Table 1). Encouraged by its potent in vitro activity, we evaluated its cellular activity in inhibiting CREB-mediated gene transcription by a CREB-reporter assay in HEK 293T cells. Therefore, HEK 293T cells were transfected with CRE-RLuc, a plasmid expressing RLuc under the control of three tandem copies of CRE.10 Then the transfected cells were treated with different concentrations of compound 1 before stimulating the cells with forskolin (10 μM). The data presented in Figure 2B and Table 1 showed that compound 1 inhibited CREB-mediated gene transcription in living HEK 293T cells with an IC50 of 2.09 μM. To investigate if the inhibition of the CREB's transcription activity by compound 1 was dependent on KIX-KID interaction, another transcription reporter assay activated by a heterologous transcription activator, VP16-CREB, was performed in HEK 293T cells. VP16-CREB fusion contains full length CREB and the potent transcription activation domain VP16.10,23 Unlike CREB whose transcription activity is dependent on phosphorylation at Ser133, VP16-CREB is a constitutively active transcription activator and its transcription activity is independent of phosphorylation at Ser133.10,23 To this end, HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with VP16-CREB and CRE-RLuc. The transfected cells were then treated with increasing concentrations of compound 1. The results presented in Figure 2C showed that 1 also inhibited VP16-CREB-mediated gene transcription with an IC50 of 6.14 μM (Table 1). Although this is about 3-fold higher than the IC50 of CREB-mediated gene transcription (Figure 2B), these results suggest that compound 1 is not particularly selective in inhibiting KIX-KID interaction inside the living cells.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of KIX-KID interaction and CREB-dependent gene transcription by 1 and 4. (A) Inhibition of in vitro KIX-KID interaction. RLuC-KIX and KID-RLucN were combined together in the presence of different concentrations of compounds at 4 °C. The residual RLuc activity was measured after 20 h of incubation. (B) Inhibition of CREB-dependent gene transcription. HEK 293T cells were transfected with CRE-RLuc and then treated with different concentrations of compounds for 30 min. Then forskolin (10 μM) was added and incubated for another 5 h. The cells were then lysed and the RLuc activity was measured. The RLuc activity was normalized to protein concentration and expressed as RLU (relative light units)/μg protein. (C) Inhibition of VP16-CREB-mediated gene transcription. The experiments were the same as in (B) except the cells were transfected with VP16-CREB and CRE-RLuc and forskolin treatment was omitted.

Table 1.

Biological activities of synthesized compounds.a

| compound | KIX-KID inhibition (IC50) b | CREB-mediated transcription inhibition (IC50) b | VP16-CREB-mediated transcription inhibition (IC50) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 2.09 ± 0.39 | 6.14 ± 0.88 |

| 4 | 0.41±0.067 | 9.42 ± 0.47 | 13.17 ± 4.41 |

| 6 | 7.14 ± 0.57 | 13.74 ± 3.41 | >100 |

| 7 | ∼50c | ∼50c | >50 |

| 8 | 0.17 ± 0.064 | >50 | NDd |

| 9 | 13.06 ± 3.69 | >50 | NDd |

| 9a | >50 | >50 | NDd |

All the stock solutions were prepared in DMSO except 9, which was dissolved in DMF due to its instability in DMSO.

All the IC50 values are shown in μM. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least two independent experiments performed in duplicates (KIX-KID inhibition assay) or triplicates (reporter assays). If the IC50 was not reached at the highest concentration tested at 50 μM or 100 μM, it is presented as >50 or >100.

The IC50 is roughly at the highest concentration tested.

Not determined.

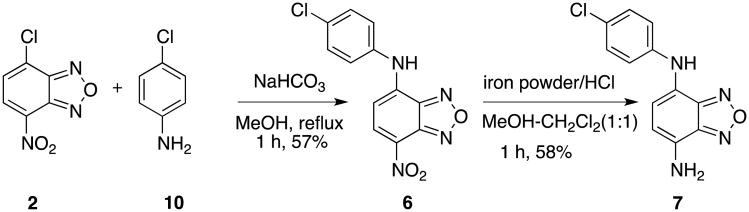

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 6 and 7.

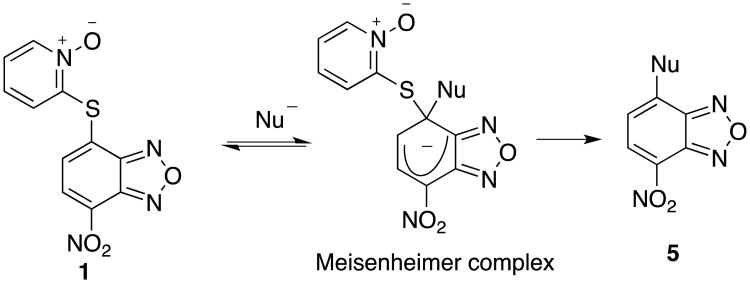

We hypothesized that compound 1 might form a Meisenheimer-type complex with cellular nucleophiles (e.g. glutathione and protein cysteine side chain) eventually leading to elimination of 2-pyridinethiol 1-oxide and form a covalent adduct 5 (Figure 3),24 which may account for its limited selectivity. Therefore, the electrophilicity of benzofurazan nucleus and leaving group ability of the appendant aromatic rings were modulated with a goal of trying to enhance the selectivity. This led to the design and synthesis of compounds 4, 6-9 (Schemes 1-3). The relative leaving group ability follows the order of 1 > 4 > 6 while compound 7 has reduced capability to form a Meisenheimer-type complex due to the electron-donating nature of the –NH2 group. Compounds 8 and 9 do not have a leaving group and thus cannot form the corresponding adduct 5.

Figure 3.

Potential formation of a Meisenheimer complex between compound 1 and cellular nucleophiles.

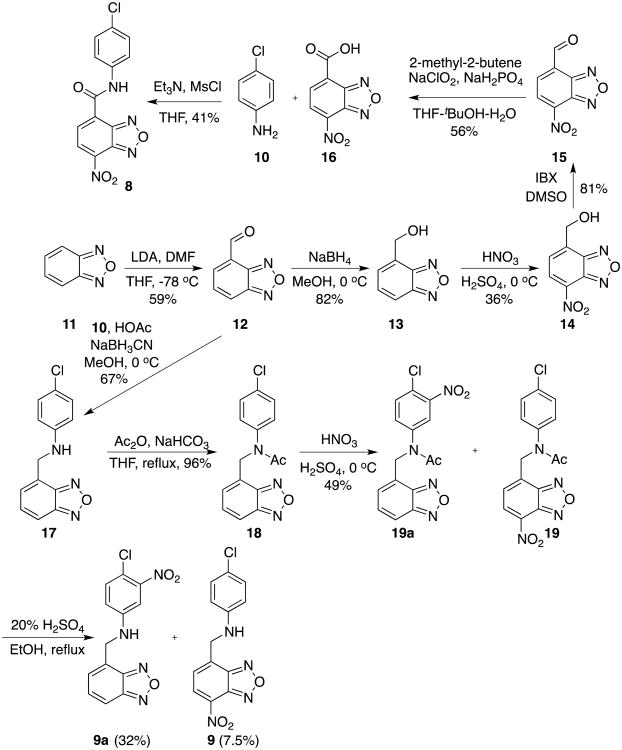

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 8 and 9.

Compound 6 was synthesized by condensing NBD-Cl (2) with 4-chloroaniline (10) in the presence of NaHCO3 (Scheme 2).20,25 Reduction of –NO2 in 6 with Fe/HCl26 gave compound 7 in 58% yield. In order to synthesize compound 8, we designed the synthesis by coupling a known acid 1627 with aniline 10. Acid 16 was reported to be prepared from commercially available benzofurazan (11) by a sequence of reactions involving formylation by LDA/DMF, reduction by NaBH4, concomitant nitration and oxidation by HNO3/H2SO4.27 However, we were only able to obtain alcohol 14 from this series of reactions. The acid 16 was eventually prepared from alcohol 14 via IBX oxidation followed by Pinnick oxidation.28 The desired amide 8 was finally delivered by coupling acid 16 with aniline 10 facilitated by MsCl.20 The synthesis of compound 9 was not so straightforward. Initial attempts to prepare 9 from Borch reductive amination29 between aldehyde 15 and 10 were unsuccessful. We found that the nitro group in 15 had deleterious effects on this reaction because aldehyde 12 could be successfully coupled with aniline 10 to give 17 in 67% yield under the same reaction condition. Direct nitration of 17 only afforded the undesired product with a nitro group incorporated into the aniline ring presumably due to its electron-rich nature. So an acetyl group was introduced on the aniline nitrogen to generate 18 by decreasing its nucleophilicity. Nitrating 18 gave a chromatographically inseparable mixture of 19a and 19 in a combined 49% yield in a ratio of 69:31 as determined by HPLC. Final hydrolysis of the acetyl group in the mixture of 19a and 19 with 20% H2SO4/EtOH yielded products 9a and 9, which could be separated by careful silica gel chromatography (Scheme 3).

All the six newly synthesized compounds were evaluated for their potencies in inhibiting KIX-KID interaction in vitro and CREB-mediated gene transcription. For those compounds demonstrating inhibition of CREB's activity, their effects on VP16-CREB-mediated gene transcription in HEK 293T cells were also evaluated. The results are presented in Figure 2 and Table 1. The deoxygeneated compound 4 displayed comparable activity to compound 1 in inhibiting KIX-KID interaction in vitro, suggesting the scheme shown in Figure 3 is not a major pathway for the observed in vitro inhibition of KIX-KID interaction because thiopyridine 1-oxide is a better leaving group than thiopyridine. On the other hand, the cellular inhibition of CREB-mediated gene transcription by 4 was reduced by about 4-fold to an IC50 of 9.42 μM compared to compound 1. These results suggest that the discordance between in vitro and cellular IC50 of compound 1 is not due to its charged nature, which may result in reduced cell permeability as compound 4 is not charged. But its cellular potency is also much weaker than its in vitro KIX-KID interaction inhibition potency. Compared to compound 1, the selectivity of deoxygenated compound 4 was not improved because it inhibited VP16-CREB-mediated gene transcription with an IC50 of 13.17 μM. The 4-chloroaniline-substituted compound 6 was significantly less potent in inhibiting KIX-KID interaction in vitro (IC50 = 7.14 μM) than 1. Its cellular activity (IC50 = 13.74 μM) was only ∼2-fold less potent than its in vitro activity. More importantly, this compound displayed enhanced selectivity as evidenced by the lack of inhibition of VP16-CREB-mediated transcription activity up to 100 μM, the highest concentration tested. Reduction of the –NO2 group in 6 to compound 7 essentially abolished all the activities measured (Table 1). The amide compound 8 exhibited two-fold enhanced activity in inhibiting KIX-KID interaction in vitro (IC50 = 0.17 μM) compared to 1. However, no cellular activity was observed (IC50 >50 μM). This discrepancy might be due to its poor cellular permeability or extracellular inactivation. Insertion of one methylene unit into compound 6 resulted in 9, which showed reduced in vitro and cellular activity. The regioisomer 9a was inactive in all the assays measured. Collectively, these results suggest that the electrophilic nature of the nitrobenzofurazan nucleus is required for potent KIX-KID interaction inhibition and cellular inhibition of CREB-mediated gene transcription. Furthermore, modulation of leaving group ability of the substituents at 4-position of nitrobenzofurazan can enhance selectivity.

In summary, 2-[(7-nitrobenzo[c][1,2,5]oxadiazol-4-yl)thio]pyridine 1-oxide (compound 1) was identified as a novel inhibitor of KIX-KID interaction from screening the NCI diversity set of compounds using a split RLuc assay. Nitrobenzofurazan derivatives have recently been found to display other significant biological activities including inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 2 (HIF-2),30 inhibition of oncogene c-Myc,31 and inhibition of aldose reductase.32,33 However, the structure-activity relationship is unique in each case, suggesting distinct binding modes with different proteins. Although compound 1 was a potent inhibitor of KIX-KID interaction (IC50 = 0.36 μM), it was not particularly selective against CREB-mediated gene transcription in HEK 293T cells. Further structure-activity relationship studies showed that 4-aniline substituted compound 6 displayed a higher selectivity index. Therefore, compound 6 represents a novel small molecule inhibitor of CREB-mediated gene transcription that can be further developed into more selective and potent inhibitors for detailed biological evaluations.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM087305). C.B. was an OHSU Equity Scholar. We thank Dr. Andrea DeBarber (Oregon Health & Science University) for expert mass spectroscopic analyses and the Development Therapeutics Program at the National Cancer Institute for providing the compound library.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Montminy MR, Bilezikjian LM. Nature. 1987;328:175. doi: 10.1038/328175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR. Cell. 1989;59:675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radhakrishnan I, Perez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Cell. 1997;91:741. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayr B, Montminy M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagiwara M, Alberts A, Brindle P, Meinkoth J, Feramisco J, Deng T, Karin M, Shenolikar S, Montminy M. Cell. 1992;70:105. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90537-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadzinski BE, Wheat WH, Jaspers S, Peruski LF, Lickteig RL, Johnson GL, Klemm DJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2822. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu T, Zhang Z, Wang J, Guo J, Shen WH, Yin Y. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2821. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao X, Li BX, Mitton B, Ikeda A, Sakamoto KM. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10:384. doi: 10.2174/156800910791208535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li BX, Xiao X. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:2721. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majmudar CY, Hojfeldt JW, Arevang CJ, Pomerantz WC, Gagnon JK, Schultz PJ, Cesa LC, Doss CH, Rowe SP, Vasquez V, Tamayo-Castillo G, Cierpicki T, Brooks CL, III, Sherman DH, Mapp AK. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:11258. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang N, Majmudar CY, Pomerantz WC, Gagnon JK, Sadowsky JD, Meagher JL, Johnson TK, Stuckey JA, Brooks CL, III, Wells JA, Mapp AK. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3363. doi: 10.1021/ja3122334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao J, Stagno JR, Varticovski L, Nimako E, Rishi V, McKinnon K, Akee R, Shoemaker RH, Ji X, Vinson C. Mol Pharmacol. 2012;82:814. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Best JL, Amezcua CA, Mayr B, Flechner L, Murawsky CM, Emerson B, Zor T, Gardner KH, Montminy M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406374101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao X, Yu P, Lim HS, Sikder D, Kodadek T. J Comb Chem. 2007;9:592. doi: 10.1021/cc070023a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li BX, Yamanaka K, Xiao X. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:6811. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, Li BX, Xie F, Delaney F, Xiao X. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4020. doi: 10.1021/jm300043c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman KM, Tizkova K, Reszka AP, Neidle S, Thurston DE. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:3006. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sierecki E, Sinko W, McCammon JA, Newton AC. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6899. doi: 10.1021/jm100331d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selected characterization data for selected compounds: (a) Compound 1: a yellow solid, m.p. 201-202 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.70 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 1 H), 8.45 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.05 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.39 (brs, 1 H), 7.25 (s, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 151.20, 146.54, 143.94, 139.05, 137.48, 137.10, 132.31, 128.99, 126.35, 126.24, 124.74; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H7N4O4S+ (M + H)+ 291.01825, found 291.01830. (b) Compound 4: a yellow solid, m.p. 81-82 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.62 (dd, J = 4.7, 1.2 Hz, 1 H), 8.40 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.83 (td, J = 7.7, 1.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1 H), 7.61 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1 H), 7.38 (dd, J = 4.9, 0.9 Hz, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.10, 151.06, 149.51, 142.65, 138.15, 136.84, 130.49, 127.58, 126.36, 123.86; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C11H7N4O3S+ (M + H)+ 275.02334, found 275.02342. (c) Compound 6: a red solid, m.p. 156-157 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.04 (s, 1 H), 8.54 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1 H), 7.57 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.51 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.76 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 145.54, 144.64, 142.40, 137.99, 137.35, 130.69, 130.07, 125.94, 124.10, 102.65; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C12H6ClN4O3- (M - H)- 289.01229, found 289.01255. (d) Compound 8: an orange solid, m.p. 229-230 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.97 (s, 1 H), 8.82 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 8.25 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1 H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2 H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.60, 148.27, 143.12, 137.68, 137.18, 131.62, 131.36, 130.55, 128.88, 128.27, 121.80; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C13H6ClN4O4- (M - H)- 317.00721, found 317.00777.

- 21.Hay BP, Beckwith ALJ. J Org Chem. 1989;54:4330. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponaras AA, Zaim O. J Heterocycl Chem. 2007;44:487. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tao X, Finkbeiner S, Arnold DB, Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. Neuron. 1998;20:709. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh PB, Whitehouse MW. J Med Chem. 1968;11:305. doi: 10.1021/jm00308a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyne B, Ahmed S, Scaiano JC. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:354. doi: 10.1039/b713575k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao XS, Fanwick PE, Cushman M. Synth Commun. 2004;34:3901. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salvati ME, Balog JA, Pickering DA, Giese S, Fura A, Li W, Patel RN, Hanson RL, Mitt T, Roberge JY, Corte JR, Spergel SH, Rampulla RA, Misra RN, Xiao HY. (USA) Application: US. US: 2004. p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bal BS, Childers WE, Jr, Pinnick HW. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:2091. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borch RF, Bernstein MD, Durst HD. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2897. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheuermann TH, Li Q, Ma HW, Key J, Zhang L, Chen R, Garcia JA, Naidoo J, Longgood J, Frantz DE, Tambar UK, Gardner KH, Bruick RK. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:271. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yap JL, Wang H, Hu A, Chauhan J, Jung KY, Gharavi RB, Prochownik EV, Fletcher S. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:370. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sartini S, Cosconati S, Marinelli L, Barresi E, Di Maro S, Simorini F, Taliani S, Salerno S, Marini AM, Da Settimo F, Novellino E, La Motta C. J Med Chem. 2012;55:10523. doi: 10.1021/jm301124s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tholander F, Sjoberg BM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113051109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]