Abstract

We present a 9-year-old boy with history of perinatal asphyxia and neonatal seizures; who presented with delayed development of speech, with predominant dysarthria, dysphagia, and drooling of saliva and unable to protrude tongue along with delayed motor and mental milestones. He had complex partial seizures since last 3 years requiring multiple anti-epileptic drugs. He had dysarthria, nasal twang, and drooling of saliva with difficulty in chewing and swallowing. Hearing and understanding were normal. Bilateral trigemino-facio-linguo-pharyngeal palsy was noticed on voluntary movements with normal jaw jerk with preserved automatic and emotional motor movements. Electroencephalography revealed focal left fronto-temporal epileptiform discharges and brain imaging was suggestive of bilateral cortical and subcortical region encephalomalacia, predominantly involving bilateral opercular region. The clinical and neuroimaging features correspond to bilateral opercular syndrome which could have resulted from the perinatal insult in this case.

Keywords: Dysarthria, dysphagia, opercular syndrome, seizures

Introduction

The ‘Opercular syndrome’, also known as Foix-Chavany-Marie syndrome was first reported in 1926, but was described first by Magnus in 1837.[1,2] This term is usually used in relation to adults as it refers to damage that is acquired later in life. The developmental form of communication disorder is described as Worster-Drought syndrome.[3] Controversy exists in the literature regarding the nomenclature of these various developmental and acquired disorders with characteristic clinical presentation, caused by lesions involving the peri-sylvian opercular cortex, which is the area on the motor homunculus responsible for motor control of the face and mouth.

Case Report

A 9-year-old male presented with unclear and slurred speech, drooling of saliva and inability to protrude tongue and difficulty swallowing since early childhood. He was born with emergency caesarean section (due to fetal distress) and birth weight was 2.5 kg. He developed seizures at 6 hours of life due to perinatal asphyxia, for which he was admitted in neonatal intensive care unit for a week. He had motor and cognitive delay with involvement of speech domain greater than social and motor domain. At the age of 6 years; he developed seizures which were brief, tonic-clonic, involving right side of body with loss of consciousness. Seizures were poorly controlled on multiple anti-epileptic drugs regimen consisting of sodium valproate, lamotrigine, and clobazam. He had no history of trauma, surgery. Family history was not significant.

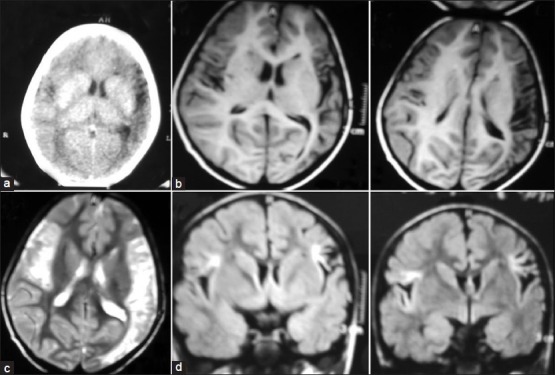

He had dysarthria with nasal twang in voice, mouth half open and not able to close volitionally. He was unable to bring out the tongue beyond lower incisor. Hearing and understanding were normal. There was no tongue tie or any structural defect of tongue. Bilateral trigemino-facio-linguo-pharyngeal palsy was noticed on volitional control but automatic and emotional motor movements were well preserved. He was able to blink, close his eyes completely while sleeping, and move the jaw and facial muscles with spontaneous emotional responses like laughing or crying. There was no wasting or fasciculations of the tongue. There was hypertonia in all four limbs and deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated with normal jaw jerk along with extensor bilateral plantars. Electroencephalography (EEG) findings consisted of focal left fronto-temporal epileptiform discharges and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain revealed bilateral fronto-temporal and parietal cortical and subcortical region encephalomalacia, with involvement of opercular region [Figure 1]. Induced sleep EEG did not reveal any continuous spike and wave discharges as seen in Continuous Spike and Wave discharges in Sleep (CSWS) or Landau-Kleffner syndrome (LKS).

Figure 1.

(a) Axial CT scan (b) axial T1 MRI (c) axial T2 MRI (d) FLAIR coronal MRI images showing bilateral fronto-temporal and parietal cortical (left > right) and subcortical (right > left) region encephalomalacia, with predominant involvement of anterior frontal opercular region

Based on above clinical findings, a diagnosis of acquired bilateral opercular syndrome due to perinatal asphyxia was considered.

Discussion

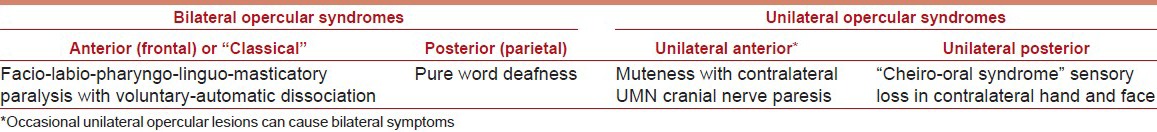

The ‘opercular syndrome’ consists of the clinical syndrome of bilateral corticobulbar involvement with facio-labio-pharyngo-glosso-laryngo-brachial paralysis on voluntary movement of these muscles, but well-preserved automatic and reflex movements of the same muscles due to lesions at cortical or subcortical region involving the anterior opercular area surrounding the insula formed from gyri of the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes.[4] Operculum means ‘mouth’ and the term often refers to the fold that is clearly visible on each side of the perisylvian region of cerebral hemispheres. It is often grouped as perisylvian-opercular syndrome which could be congenital or acquired; transient, intermittent or persistent type with heterogeneous etiologies. It has been classified into anterior and posterior subtypes and unilateral and bilateral types [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical types of opercular syndrome

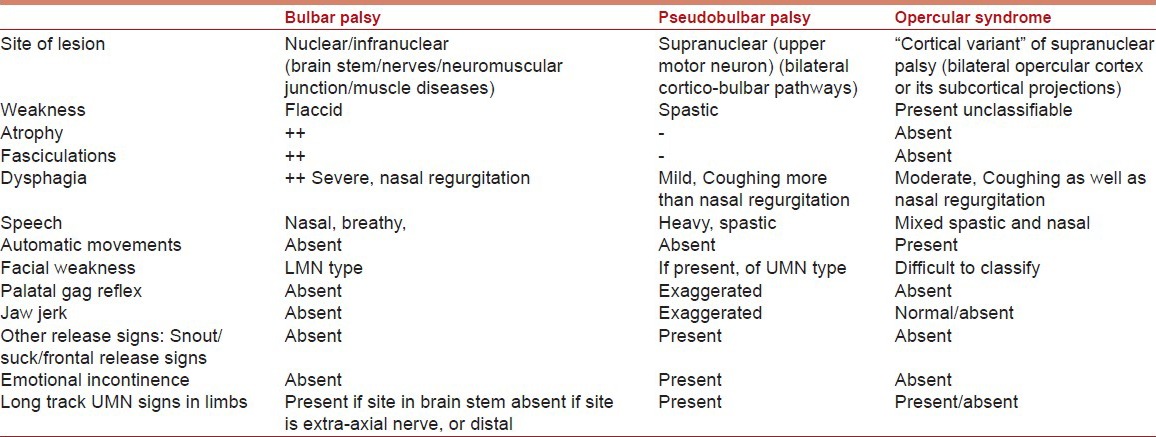

Voluntary control of face, tongue, and pharynx movement requires intact primary motor cortices and pyramidal pathways between the areas and the brain-stem, containing the relevant cranial nerve nuclei. Any lesions involving the motor cortices, subcortical areas, or pyramidal pathways bilaterally produce a selective palsy of voluntary use of the facial, pharyngeal, and masticatory muscles, on the other hand spontaneous, emotional control of the same muscles requires intact extrapyramidal pathways and probably portions of the thalamus and hypothalamus.[5] Bilateral opercular lesions typically impair the voluntary movements of the facial, lingual, pharyngeal, and masticatory with preservation of the automatic-emotional movements which is the classical presentation of this syndrome. This phenomenon often referred to as “facio-labio-pharyngeo-linguo-masticatory paralysis with automato-voluntary dissociation” helps in clinically differentiating the opercular syndrome from the pseudo bulbar palsy associated with bilateral supra-bulbar lesions [Table 2].

Table 2.

Differentiating opercular syndrome from bulbar and pseudobulbar syndrome in patients with dysphagia and dysarthria

The actual incidence is unknown. Case reports with varied etiologies including perinatal insults, cerebrovascular disease, trauma, surgery, tumor, herpes encephalitis, toxoplasmosis, other meningoencephalitis, inflammatory demyelinating lesions, and developmental malformations like poly-microgyria or heterotopias are found to be associated. Acquired epileptiform opercular syndrome is a distinct epileptic syndrome, equivalent to the Landau-Kleffner syndrome (where language is impaired), has also been described where acquired dysarthria is associated with electrographic status epilepticus in the form of continuous spike and wave discharges during sleep (CSWS). Congenital bilateral Perisylvian Opercular syndrome described by Kuzniecki,[6] is usually caused by fetal developmental abnormalities has been found to be associated with Xq27.2-q27.3, Xq2822q11.2 mutation, but may also occur from early fetal insults like fetal vascular insult or intra-uterine infections in early pregnancy. Its severest form presents in neonates, with difficulty sucking breast milk and recurrent aspiration. Usual symptoms are dysarthria, dysphagia, and difficulty in chewing, blowing, moving the tongue, and swallowing difficulty which are affected more than motor and social milestones. Developmental delay is seen in 60% cases and mild-moderate mental retardation seen in 50-80% cases. Epilepsy is seen in 87-90% cases, focal seizures with secondary generalization are common, but all types of seizures are reported, and are refractory to treatment in two-thirds.

The prognosis is variable, dependent on the severity of clinical disease, the type of the etiology, and the time of diagnosis. In disorders like meningo-encephalitis, vascular or traumatic insult, the epileptic opercular syndrome may be transient and reversible; while developmental and perinatal insults are likely to be permanent. If the cause can be established early, early treatment may prevent residual sequelae.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gordon N. The opercular syndrome, or, the Foix-Chavany-Marie syndrome. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2007;37:103–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thapa L, Paudel R, Rana PV. Opercular syndrome: Case reports and review of literature. Neurol Asia. 2010;15:145–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christen HJ, Hanefeld F, Kruse E, Imhäuser S, Ernst JP, Finkenstaedt M. Foix-Chavany-Marie (anterior operculum) syndrome in childhood: A reappraisal of Worster-Drought syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:122–32. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Ribes A, Martínez-González MJ, Prats-Viñas JM. Suspected herpes encephalitis and opercular syndrome in childhood. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:202–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakar M, Kirshner HS, Niaz F. The opercular-subopercular syndrome: Four cases with review of the literature. Behav Neurol. 1998;11:97–103. doi: 10.1155/1998/423645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzniecky R, Andermann F, Guerrini R. Congenital bilateral perisylvian syndrome: Study of 31 patients. The CBPS Multicenter Collaborative Study. Lancet. 1993;341:608–12. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90363-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]