Abstract

Valproic acid (VPA) is widely used as an anti-epileptic drug. The primary mechanism of VPA toxicity is interference with mitochondrial beta-oxidation, and it can exacerbate an underlying mitochondrial cytopathy. We report a case of Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes unmasked by use of Sodium Valproate in a 12-year-old boy who presented with headache and seizures. There was precipitation of encephalopathy, myopathy, lactic acidosis, and hepatic damage within two days of valproate use, after withdrawing of which there was a remarkable clinical and biochemical recovery.

Keywords: Cytopathy, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke-like episodes, sodium valproate

Introduction

Valproic acid (VPA: 2-n-propylpentanoic acid) is widely used as an anti-epileptic drug (AED). The primary mechanism of VPA toxicity is interference with mitochondrial beta-oxidation, because of its structural resemblance to simple fatty acid,[1] and it is known to cause exacerbation of an underlying mitochondrial cytopathy.[2,3,4,5] Here, we report a previously healthy young boy, in whom use of Sodium Valproate for seizures unveiled an underlying mitochondrial cytopathy, most likely Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS).

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy presented with headache, vomitings, and seizures of two weeks duration. The headaches were predominantly left-sided, severe, throbbing, associated with vomiting, lasting each time for 1-2 hours, and recurring 2-3 times in a day. There was no postural or diurnal variation of the headaches nor any associated fever, neck pain, visual symptoms, or focal neurological deficit. On second day of the onset of headache, he had three episodes of GTCS. He presented to us almost two weeks into the illness wherein the seizures did not recur, but the headache persisted. He was started on Sodium Valproate 400 mg/day, but within two days of starting treatment, he experienced worsening of headache, repeated bouts of vomiting, and recurrence of seizures. The child became very dull and lethargic. He also developed certain new symptoms in form of pain and weakness in lower limbs, with difficulty in getting up from squatting position, and requiring one person support for walking. There was no history of any difficulty in gripping or slippage of slippers, any weakness in upper limbs, sensory loss, limb incoordination, bladder bowel or cranial nerve involvement.

His general physical and systemic examination was unremarkable; in particular, there was no fever, jaundice, abdominal tenderness, or any organomegaly. The child was conscious, oriented to time, place and person but very lethargic and irritable. There were no signs of meningeal irritation. On motor system examination, muscle tone and nutrition was normal. There was tenderness over muscles of arms and thighs, and he did not allow formal testing of muscle power, though he was moving all limbs equally in bed. Deep tendon reflexes were normally elicitable, and planters were bilaterally flexors. Sensory examination was normal, and there were no cerebellar signs.

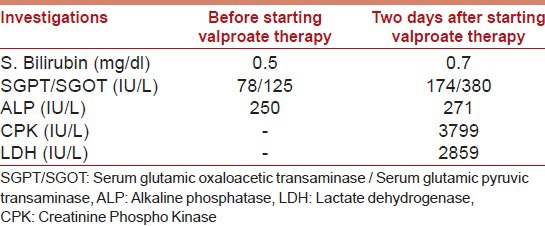

His routine investigations including hemogram, complete blood count, renal function tests, and serum electrolytes were normal. There was a worsening of liver functions as well as a rise in LDH and CPK levels after starting Valproate [Table 1]. His serum lactate was 16.7 mg/dl (normal range 8-16 mg/dl). Viral markers including HIV, HBsAg, and anti-HCV all were all negative.

Table 1.

Investigations after starting Valproate

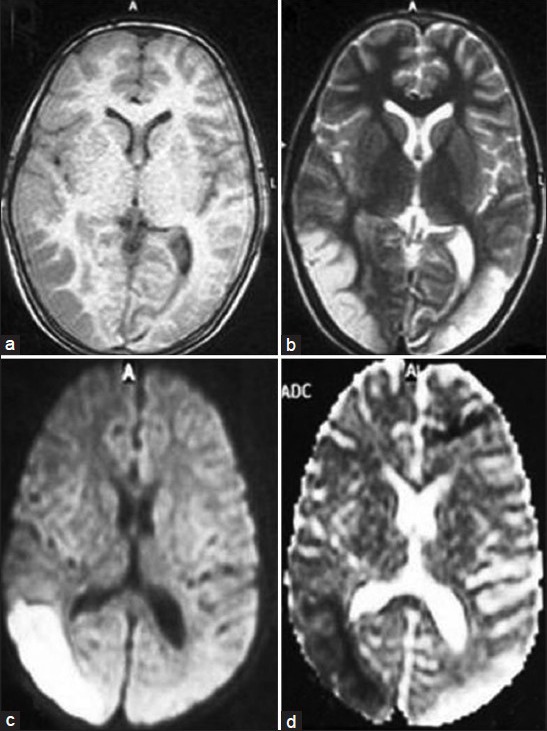

His X-ray chest, USG abdomen, 2D-Echo all were normal. MRI brain revealed an acute infarct in left occipito-temporal region and an old infarct in right occipito-temporal area [Figure 1a-d] with normal MR angiogram and MR venogram [Figure 2a and b]. A possibility of valproate-induced myositis and hepatotoxicity were considered with probability of an underlying mitochondrial disorder, likely MELAS.

Figure 1.

(a and b) Axial T1- and T2-weighted images showing infarcts in bilateral occipito-temporal regions. (c and d) Axial DWI and ADC showing an acute infarct in left and an old infarct in right occipito-temporal areas

Figure 2.

(a and b) Normal MR angiogram and MR venogram

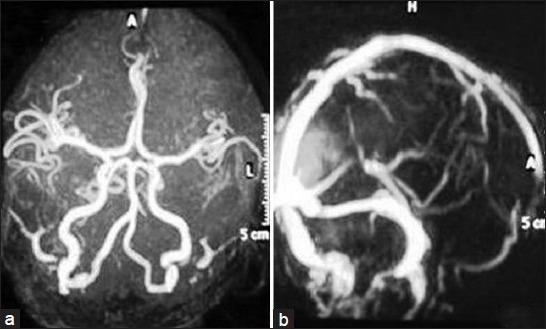

Valproate was stopped, and patient was loaded with intravenous Levetiracetam 1000 mg and continued on maintenance dose of 500 mg twice-daily. He started improving within 24 hours, became more active, pain and weakness in limbs decreased and abated completely over the next five days. There was no recurrence of seizures. The laboratory parameters also improved subsequently after stopping valproate [Table 2].

Table 2.

Investigations after stopping Valproate

Muscle biopsy from vastus lateralis revealed maintained fascicular architecture with minimal variation of fiber size. Intermyseal and perimyseal connective tissue was unremarkable. NADH and SDH stain revealed normal fiber typing and myofibrillar architecture. No ragged red fibers were identified on Gomori trichrome stain. After two weeks of hospital stay, he was discharged on Levetiracetam (500 mg twice-daily), CoQ10 (30 mg twice-daily), Levocarnitine 330 mg twice-daily), and cocktail of multivitamins (B complex including B1, B2, B12, folate, niacin, biotin, pyridoxine; vitamin A, vitamin C, along with iron, zinc, magnesium, chromium, selenium, L-methionine, L-arginine).

Discussion

Medications and toxins significantly affect mitochondrial function. Infact, mitochondrial dysfunction is a major mechanism of drug-induced hepatotoxicity, lactic acidosis, myopathy, pancreatic dysfunction, rhabdomyolysis, renal tubular dysfunction, cardiomyopathy, and cardiac conduction defects.[6,7] There is a long list of mitochondrion-toxic agents that includes corticosteroids, valproate, phenytoin, barbiturates, propofol, volatile anesthetics, non-depolarizing muscle relaxants, statins, fibrates, biguanides, glitazones, beta-blockers, amiodarone, and NRTIs.[6,7] Sodium valproate impairs mitochondrial function by the induction of carnitine deficiency, depression of beta-oxidation of fatty acids, and inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation; hence, its use as an anti-epileptic is contraindicated in mitochondrial disorders.

In our patient, use of Sodium valproate for seizures lead to an aggravation of seizures, and precipitation of a myopathy associated with lactic acidosis and hepatic dysfunction. This made us suspect an underlying mitochondrial disorder and since he had presented with migraineous headaches, seizures, with an MRI evidence of infarction, not following any vascular territory, with a normal MRV and MRA, a possibility of MELAS was considered.

MELAS is a well-established mitochondrial cytopathy with onset in childhood. It may present sporadically or as maternal inheritance pattern. Its clinical presentations are myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and/or stroke-like episodes. Stroke-like episodes are the first presentation, usually between ages of 4-15 years that may manifest with seizures, visual abnormalities, numbness, hemiplegia, and/or aphasia. Other features of MELAS are migraine-like headaches, hearing loss, cardiomyopathy, cardiac conduction defects, short stature, exercise intolerance, endocrinopathies, neuropsychiatric dysfunction, developmental delay, and learning disability.[8,9,10] Muscle biopsy classically demonstrates ragged red fibers on modified Gomori trichrome stain in at least 85% of cases; however, a negative muscle biopsy does not rule out this disease.[10] The diagnostic criteria proposed for MELAS are:[1] Stroke-like episode before age 40 years,[2] encephalopathy characterized by seizures, dementia, or both; and[3] lactic acidosis, ragged-red fibers (RRF), or both.[10] Our patient fulfills all the above said criteria. Genetic testing could not be done in our case due to financial constraints.

So, our case demonstrates an unveiling of mitochondrial cytopathy, in all probability MELAS, by Sodium valproate and suggests that in patients whose seizures worsen with valproate therapy, an inborn error of mitochondrial metabolism should be suspected. The underlying mitochondrial DNA defects should be sought for family screening and genetic counseling.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Silva MF, Aires CC, Luis PB, Ruiter JP, Jlst LI, Duran M, et al. Sodium Valproate metabolism and its effects on mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation: A review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:205–16. doi: 10.1007/s10545-008-0841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krähenbühl S, Brandner S, Kleinle S, Liechti S, Straumann D. Mitochondrial diseases represent a risk factor for valproate-induced fulminant liver failure. Liver. 2000;20:346–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lam CW, Lau CH, Williams JC, Chan YW, Wong LJ. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) triggered by valproate therapy. Eur J Pediatr. 1997;156:562–4. doi: 10.1007/s004310050663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin CM, Thajeb P. Sodium Valproate aggravates epilepsy due to MELAS in a patient with an A3243G mutation of mitochondrial DNA. Metab Brain Dis. 2007;22:105–9. doi: 10.1007/s11011-006-9039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YM, Lin CM, Thajeb P. Paradoxical effect of sodium valproate that aggravates epilepsy of MELAS in a patient with A3243G mutation of the mitochondrial DNA. Cent Eur J Med. 2007;2:103–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labbe G, Pessayre D, Fromenty B. Drug-induced liver injury through mitochondrial dysfunction: Mechanisms and detection during preclinical safety studies. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:335–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neustadt J, Pieczenik SR. Medication-induced mitochondrial damage and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:780–8. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto Y, Horai S, Matsuoka T, Koga Y, Nihei K, Kobayashi M, et al. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS): A correlative study of the clinical features and mitochondrial DNA mutation. Neurology. 1992;42:545–50. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenzoni PJ, Scola RH, Kamoi Kay CS, Arndt RC, Freund AA, Bruck I, et al. MELAS: Clinical features, muscle biopsy and molecular genetics. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67:668–76. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2009000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirano M, Ricci E, Koenigsberger MR, Defendini R, Pavlakis SG, DeVivo DC, et al. MELAS: An original case and clinical criteria for diagnosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 1992;2:125–3. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(92)90045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]