Abstract

Introduction:

Mononeuropathies, in general, are very uncommon in childhood. Sciatic neuropathy (SN) is probably underappreciated in childhood and likely to represent nearly one quarter of childhood mononeuropathies.

Materials and Methods:

We present a 7-year-old girl who presented with painful right lower limb and abnormal gait. Detailed investigation revealed transient eosinophilia, abnormal neurophysiology, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggestive of isolated sciatic neuropathy.

Results:

She has responded very well to physiotherapy and has made a complete motor recovery, although she is left with an area of abnormal sensation affecting the lateral border of her right leg and the dorsum of her foot.

Discussion:

Differential diagnoses for pediatric SN have been discussed including compressive neuropathies in children and various hyper-eosinophilia syndromes. Compressive neuropathies in childhood are very rare and compression of the sciatic nerve is the second most common group after peroneal nerve lesion.

Keywords: Eosinophilia, hyper-eosinophilic syndrome, mononeuropathies, painful leg, sciatic neuropathy

Introduction

Mononeuropathies, in general, are rare in childhood.[1] Sciatic neuropathy (SN) accounts for nearly one-fourth of the pediatric mononeuropathies.[1] Direct trauma and iatrogenic mechanism are the most common causes for SN followed by tumor, vascular, and compression injuries.[2] Detailed review of literature reveals only a rare, brief remark that associates idiopathic causes (three cases) with SN.[2]

In children, since SN often presents with clinical features affecting the peroneal branch of the sciatic nerve, electromyography, although difficult due to poor tolerance, plays a crucial role in recognizing the presence of sciatic lesion.[3] Prognosis for recovery is variable and depends entirely on the etiology and the severity of the nerve lesion.[2]

We describe a 7-year-old girl presenting with idiopathic right sciatic neuropathy and transient blood eosinophilia presenting as painful leg who recovered almost completely with conservative management.

Case Report

A 7-year-old girl with a background of early onset childhood asthma presented with an acute exacerbation of her asthma symptoms. Apart from regular low dose inhaled steroids, she was not on any other medications. Both her past medical and family histories are not significant.

Her respiratory status gradually deteriorated despite being on intravenous salbutamol, aminophylline, and steroids. She needed intubation and mechanical ventilation for just over 24 hours after which she was successfully extubated and was recovering well.

Five days later, she reported a burning pain sensation down the whole of the right leg with some sensory disturbance, which she mainly described as “numbness”. A week later, this was followed by weakness of that leg. There was no history of trauma preceding this. Upon clinical assessment, she was noted to have a foot drop with complete inability of ankle dorsiflexion and her right ankle jerk was completely absent.

She was only able to mobilize by hopping on her left leg. There was diffuse decreased sensation to pinprick and light touch but mainly from below the right knee to the toes. The rest of the clinical examination was normal.

Extensive investigations showed a moderate eosinophilia at 1.35 × 109/L (normal range 0.05-1.0) with normal other blood counts and peripheral smear. Her eosinophilia gradually normalized in about 6 weeks. She had a normal full blood count checked prior to this admission. Concomitant with this, the IgE level was also raised at 391 KU/L (normal < 63). Her mycoplasma antibody (genetic prodrug activation therapy-GPAT) level was slightly elevated but this was thought to be of no clinical significance. The throat swab and the Anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titres did no show any evidence of a recent streptococcal infection. Moreover, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for the common respiratory viruses was negative except for rhinovirus. Her auto-antibody screen including Anti-Nuclear Antibody-Hep 2, Centromere antibody, Monoclonal IgA, IgM, and IgG and subclasses, Rheumatoid factor antibody, were normal. Urine and stool culture were negative and the screening for parasites was negative in stool and blood.

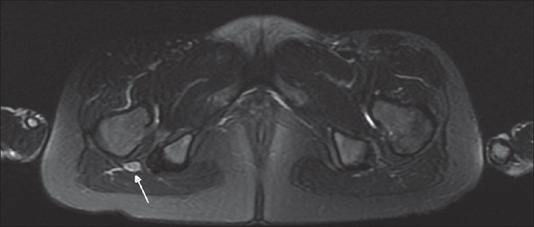

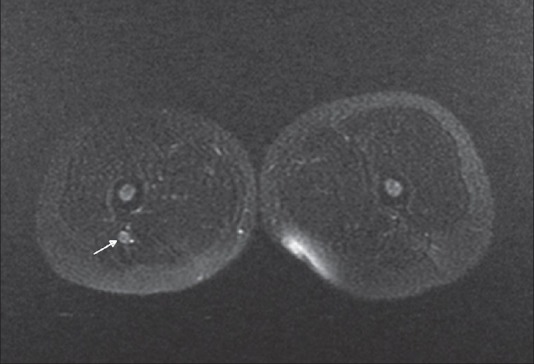

MRI demonstrated enlarged and high signal right sciatic nerve on T2-weighted images. This is seen as far down the nerve in the posterior mid thigh as imaged [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

Axial T2 MRI image of proximal thigh showing enlarged and bright right sciatic nerve

Figure 2.

Axial T2 image of the lower thigh showing enlarged and bright right sciatic nerve

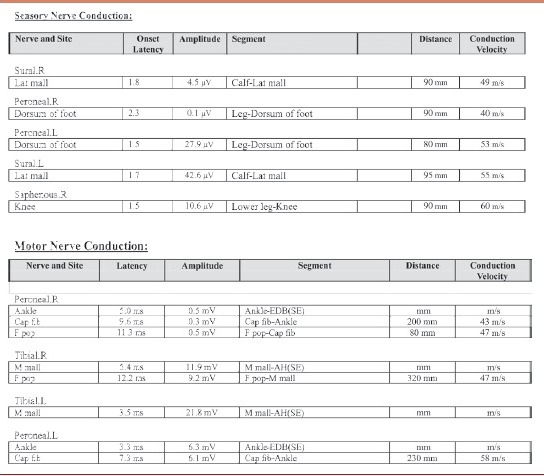

Neurophysiology examination [Table 1] was limited as she was in extreme pain. The study showed features of right sciatic mononeuropathy probably axonal in nature. The peroneal part of the sciatic nerve was more involved. Electromyography could not be performed at the request of mother; therefore, exact site of pathology was difficult to localize.

Table 1.

Sensory studies showing low amplitude sensory potentials from right sural and superficial nerves. Motor potentials showing reduced amplitude of right peroneal and right tibial motor potentials. Combination of these abnormalities would suggest sciatic nerve pathology.

Initially, the patient did have daily exacerbations of severe neuropathic pain, which was quite disabling. The pain only responded partially to trials with multiple agents including gabapentin, opiates, and carbamazepine. Fortunately, the pain started to improve after a few weeks and this was also associated with marked improvement of her muscle power. She continued to make good progress and was able to independently mobilize within 5-6 months. A year later, the patient had made a complete motor recovery, although she is left with an area of abnormal sensation affecting the lateral border of her right leg and the dorsum of her foot.

Discussion

There is a possibility that our patient could have a compressive sciatic nerve mononeuropathy.

Compressive neuropathies in childhood are very rare; only 14 of the 898 pediatric patients examined at a neurophysiology centre had compressive neuropathy.[4] It is more common in lower extremities and compression of the sciatic nerve was observed to be the second most common group after peroneal nerve lesion; of the total 14 patients, four had sciatic mononeuropathy localized to sciatic notch. Rest of the patients had compression neuropathy involving peroneal nerve (five), radial nerve (two), ulnar nerve (one), musculocutaneous nerve (one), and long thoracic nerve (one).[4]

Of note, a specific compressive mechanism was identified in each of the above 14 patients. All the four sciatic nerve lesions occurred as a result of a persistent posture. The relatively small musculature of the buttocks doesn’t offer adequate protection to the sciatic nerve in children, and as a result, immobilization appears to carry an increased risk for sciatic nerve compressive injury in children.

Our patient didn’t have any prolonged period of immobility and during her pediatric intensive care stay her posture was regularly changed to prevent any pressure sores. Also, previously described cases of compressive sciatic neuropathy didn’t have a good recovery, which is again in contrast to our case who made almost complete recovery.

Thus, although it is less likely for our case to have compressive neuropathy this cannot be completely ruled out. She doesn’t have any tendency (as yet) for repeated nerve palsies necessitating genetic testing to look for ‘hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy (HNPP), which also remains a possibility and will be looked at if further recurrences do occur.

Peripheral neuropathy and eosinophilia have been well described before in the context of ‘Eosinophilia-Myalgia syndrome (EMS)[5,6,7] and ‘Hypereosinophilic syndrome’ (HES).[8] Both these disorders are quite distinct and have mostly been described in adults.

Our patient didn’t have any myalgia or scleroderma-like changes which are characteristic features of EMS along with weakness and eosinophilia.

Similarly, although no apparent cause for eosinophilia was found in our case, it doesn’t fulfil the diagnostic criteria for HES as the eosinophilia lasted for less than 6 months, and it never reached more than 1,500/L and also there was no multi-organ involvement.[9]

Although, with the background of asthma and in the presence of eosinophilia with peripheral neuropathy, one should always consider possibility of ‘Churg-Strauss syndrome’ (CGS), this is very unlikely in our index case considering her young age, mononeuropathy and self-resolution of the disease without any course of steroids. Peripheral neuropathy associated with CGS usually presents in late adolescence and adults and is typically in the form of mononeuritis multiplex rather than mononeuropathy[10,11] as seen in this case.

Our patient initially presented with severe pain along the sciatic nerve, which was rapidly followed by development of peroneal muscles weakness leading to foot drop within a week of onset. This initial presentation with sensory symptom is a bit unusual. In the recent review of 53 patients with pediatric sciatic neuropathies, only two patients presented with sensory symptoms. Almost all the patients in their series (51) presented with foot drop (peroneal muscle weakness).[2] Numbness seems to be the predominant sensory symptom being present in all the cases. Pain as a sensory symptom was present in only eight out of 29 non-traumatic and non-surgical cases.[2]

Interestingly sciatic neuropathy with eosinophilia has been mentioned briefly once before by Srinivasan et al.[12] They described a teenager who developed SN secondary to post-streptococcal vasculitis and had raised blood eosinophils. The duration or level of eosinophilia is not available. He made a good recovery on treatment with steroids and antibiotics. Our patient showed no evidence of recent streptococcal infection, throat culture and anti-streptococcal antibodies remained negative during the course of her illness.

The Mycoplasma titres in our case did go up slightly from one in 80 to one in 160 in the first 3 months of presentation, but the microbiologist did not feel that these levels are likely to be clinically significant. The titres did fall to undetectable levels when checked again 6 months after presentation. Peripheral neuropathies secondary to Mycoplasma infection have been reported occasionally.[13,14] Immunologic mechanism is the most likely explanation and indeed anti-ganglioside antibodies in serum was observed in one study.[14]

The onset of all the three idiopathic paediatric SN cases described previously appeared to follow a viral illness.[2] In our index case, the only positive finding during her acute admission was a positive rhinovirus infection, raising again the possibility of post-viral SN as described before. The course of disease of the previously described pediatric cases is not available for comparison. Post viral SN has also been described before following herpes zoster infection.[15]

Conclusion

It does seem that our patient had amassed a very unusual eosinophilic response to her acute illness in Intensive Care Unit (ICU), but there does not seem to be any evidence of an eosinophilic syndrome and the pattern of recovery is suggestive of a single insult, with slow recovery from axonal damage.

Most likely, the sciatic neuropathy in our case appears to be post viral in nature; however, the compressive etiology cannot be ruled out for sure. Hence, the exact mechanism of injury remains unclear and perhaps further accumulation of similar case reports will be necessary to reveal the exact pathomechanisms underlying neuropathies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Jones HR, Jr, Gianturco LE, Gross PT, Buchhalter J. Sciatic neuropathies in childhood: A report of ten cases and review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 1988;3:193–9. doi: 10.1177/088307388800300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srinivasan J, Ryan MM, Escolar DM, Darras B, Jones HR. Pediatric sciatic neuropathies: A 30-year prospective study. Neurology. 2011;76:976–80. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182104394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuen EC, So YT, Olney RK. The electrophysiologic features ofsciatic neuropathy in 100 patients. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:414–20. doi: 10.1002/mus.880180408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones HR., Jr Compressive neuropathy in childhood: A report of 14 cases. Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:720–3. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heiman-Patterson TD, Bird SJ, Parry GJ, Varga J, Shy ME, Culligan NW, et al. Peripheral neuropathy associated with eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:522–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns SM, Lange DJ, Jaffe I, Hays AP. Axonal neuropathy in eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:293–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donofrio PD, Stanton C, Miller VS, Oestreich L, Lefkowitz DS, Walker FO, et al. Demyelinating polyneuropathy in eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome. Muscle Nerve. 1992;15:796–805. doi: 10.1002/mus.880150708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell D, Mackay IG, Pentland B. Hypereosinophilic syndrome presenting as peripheral neuropathy. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:429–32. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.715.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chusid MJ, Dale DC, West BC, Wolff SM. The hypereosinophilic syndrome: Analysis of fourteen cases with review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattori N, Ichimura M, Nagamatsu M, Li M, Yamamoto K, Kumazawa K, et al. Clinicopathological features of Churg-Strauss syndrome-associated neuropathy. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 3):427–39. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 18-1992. Asthma, peripheral neuropathy, and eosinophilia in a 52-year-old man. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1204–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204303261807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srinivasan J, Escolar D, Ryan M, Darras B, Jones HR. Pediatric sciatic neuropathies due to unusual vascular causes. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:738–41. doi: 10.1177/0883073808314163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Socan M, Ravnik I, Bencina D, Dovc P, Zakotnik B, Jazbec J. Neurological symptoms in patients whose cerebrospinal fluid is culture- and/or polymerase chain reaction-positive for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E31–5. doi: 10.1086/318446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshino H, Inuzuka T, Miyatake T. IgG antibody against GM1, GD1b and asialo-GM1 in chronic polyneuropathy following Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Eur Neurol. 1992;32:28–31. doi: 10.1159/000116872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wendling D, Langlois S, Lohse A, Toussirot E, Michel F. Herpes zoster sciatica with paresis preceding the skin lesions: Three case-reports. Joint Bone Spine. 2004;71:588–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]