Abstract

Background:

Nepenthes species are used in traditional medicines to treat various health ailments. However, we do not know which types of endophytic bacteria (EB) are associated with Nepenthes spp.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to isolate and to identify EB associated with Nepenthes spp.

Materials and Methods:

Surface-sterilized leaf and stem tissues from nine Nepenthes spp. collected from Peninsular Malaysia were used to isolate EB. Isolates were identified using the polymerase chain reaction-amplified 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequence similarity based method.

Results:

Cultivable, 96 isolates were analyzed; and the 16S rDNA sequences analysis suggest that diverse bacterial species are associated with Nepenthes spp. Majority (55.2%) of the isolates were from Bacillus genus, and Bacillus cereus was the most dominant (14.6%) among isolates.

Conclusion:

Nepenthes spp. do harbor a wide array of cultivable endophytic bacteria.

Keywords: 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA), bacteria, diversity, endemic, endophytes, Malaysia, Nepenthes

INTRODUCTION

Malaysia (Borneo) and Indonesia hosts the largest number of endemic Nepenthes spp.[1,2] The fluid from young unopened pitchers is used in cleaning wounds or treating incontinence, distress and pain.[3] The decoction of Nepenthes spp. aerial parts are used in the treatment of kidney stones, hypertension, fever and cough (http://www.forestry.gov.my/).

The earlier studies have shown that endophytic microorganisms isolated from medicinal plants produce the same metabolites as their hosts.[4] Therefore, there is a great potential in exploring endophytes as a source of therapeutic natural products. However, despite several traditional medicinal applications of Nepenthes spp., what types of endophytes are associated with them is not known. The objective of this study was to isolate and to identify the endophytic bacteria (EB) from Nepenthes spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nepenthes spp., namely, Nepenthes ampullaria, N. gracilis, N. macfarlanei, N. mirabilis, N. rafflesiana and N. sanguinea were collected from FRIM, Selangor, Malaysia. However, leaves and twigs from one to three individual plants of Nepenthes spp., namely, N. alba, N. albomarginata, N. gracillima and N. sanguinea were collected from the Gunung Jerai (GJ), Gurun, Kedah, Malaysia.

Leaves with petioles were thoroughly washed under running tap-water and the surface-sterilization of plant material samples was carried out as reported elsewhere.[5] The stem pieces were soaked in 70% ethanol and flamed to make their surface sterile. Aseptically, the leaf and stem tissue pieces were inoculated in the Petri plates containing Luria-Bertani (LB) agar medium. The plates were incubated in an incubator at 37°C (±3°C) for 18-20 h in the dark. The isolation, cultivation of endophytes, amplification of 16S rDNA, sequencing of 16S rDNA, identification of endophytes and rooted phylogenetic tree construction was carried out as reported by Bhore et al.[5]

RESULTS

Incubation of the inoculated leaf discs and stems pieces on LB agar medium enabled cultivable EB to grow, and the colonies of grown EB were visible on the margins of the leaf and stem tissues. Ninety-six (96) isolates from nine Nepenthes spp. were analyzed.

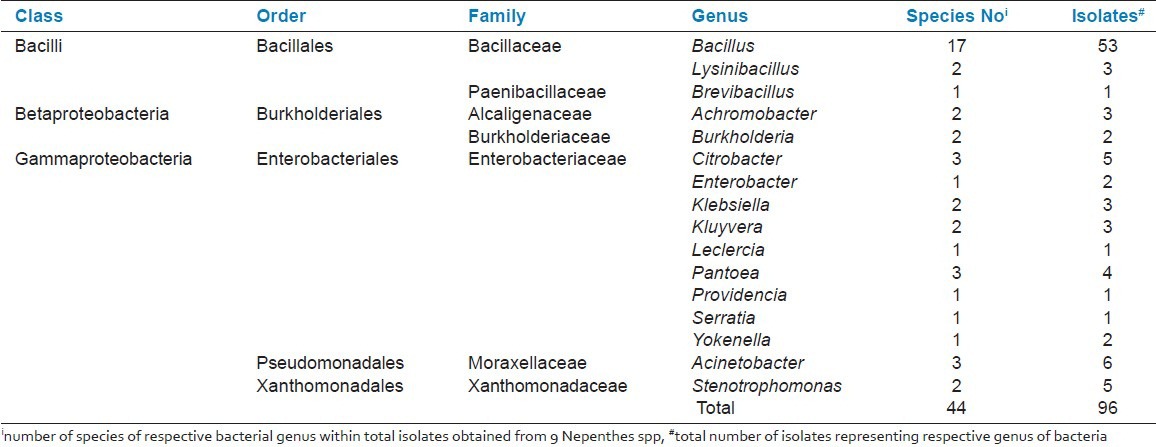

All 96 isolates were identified based on 16S rDNA sequence BLAST (megablast) hits analysis. The annotated 16S rRNA gene fragment (16S rDNA) nucleotide sequences of all isolates have been submitted to the international DNA database (GenBank/DDBJ/EMBL) under accession numbers: JF819686-JF819713 and JF938974-JF939041. Analysis of the identified isolates showed that majority of the isolates from Nepenthes spp. were from the Bacilli (59.4%) class, followed by Gammaproteobacteria (35.4%) and Betaproteobacteria (5.2%) [Table 1]. The data analysis also suggests that Bacillus spp exist in all nine Nepenthes spp.

Table 1.

The genera of endophytic bacterial isolates (EBIs) isolated from 9 Nepenthes plant species

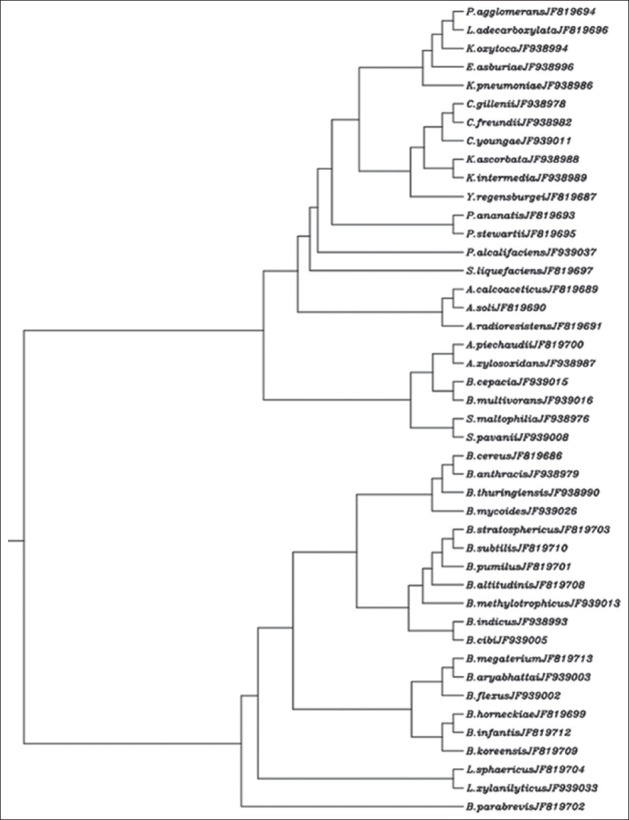

The 16S rDNA multiple sequence alignment output from CLUSTALW was used in the construction of a rooted dendrogram. The constructed dendrogram is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Rooted dendrogram showing clustering of 44 diverse types of endophytic bacteria (EB) isolated from nine Nepenthes spp. The accession number of 16S rDNA (rRNA gene) sequence of the respective isolate is given in front of the species name

DISCUSSION

In this short and snappy study, we isolated and identified 96 isolates from nine Nepenthes spp. EB have been reported from several medicinal plants, for instance Glycyrrhiza spp.,[6] Artemisia annua[7] and Gynura procumbens.[5] However, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to illustrate diversity and types of EB in nine stated Nepenthes spp.

Comparison between the annotated 16S rDNA fragment sequences from isolates and the sequences from GenBank/DDBJ/EMBL database using the BLASTN program revealed the identity of the respective isolates. It appears that the diversity of EB varies from species to species.[8] The rooted dendrogram clearly showed the clustering of the species from the Bacilli, Betaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria groups.

Endophytes are found abundantly in various plant species studied to date, and soil bacteria such as Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp. and Azospirillum spp. are commonly associated with plants as endophytes.[9,10] However, we did not find any Pseudomonas spp. and Azospirillum spp. in our isolates. During isolation of EB, the growth medium used might be directly affecting the number and type of endophytic microorganisms that can be isolated from the plant tissues. The tissue samples used in the isolation of EB were from a single or few plants of each Nepenthes spp. The location and the conditions in which plant species are grown also determine the types of endophytes in it. We have used plant samples from Nepenthes spp. that were collected from their wild habitat in GJ and diverse collection available at FRIM. This could be the reason for the wide diversity of EB in the studied Nepenthes spp. It is important to note that from 96 isolates, 22 isolates (representing 15 species) belonged to the Enterobacteriaceae family, which contains human enteric pathogens. A number of species from the Enterobacteriaceae family have been reported as endophytes, viz Entrobacter cloacae and Klebsiella pneumonia in maize, Entrobacter asburiae in cotton, and Klebsiella spp. and Entrobacter cloacae in banana.[11,12]

Of the 44 species of EB isolated from Nepenthes spp., 33 species have been reported as endophytes in various plant species. However, we have not found any published record that reported Acinetobacter soli, Bacillus cibi, B. horneckiae, B. indicus, B. koreensis, B. stratosphericus, Citrobacter gillenii, C. youngae, Kluyvera ascorbata, Providencia alcalifaciens and Serratia liquefaciens as endophytes. Perhaps, this is the first study that reports these bacterial species as endophytes. However, the benefits derived by Nepenthes spp. from these bacterial endophytes and its quantum are not clearly understood yet.

From this study, we concluded that Nepenthes spp. contains diverse types of cultivable EB, and that the majority of bacterial endophytes (59.4%) were from the Bacilli class. Nonetheless, these research findings could serve as a foundation in further research on the therapeutic properties of Nepenthes spp. in correlation with their bacterial endophytes. We hypothesize that in Nepenthes spp., these EB might be involved in producing bioactive compounds of pharmaceutical importance, and further research is required to ascertain the same.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-Based Industry (MoA), Malaysia, for financial support (Grant Code Number: 05-02-16-SF1001); BSJ acknowledges the financial support from the World Federation of Scientists (WFS) for the training of Komathi Vijayan under the national scholarship

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meimberg H, Heubl G. Introduction of a nuclear marker for phylogenetic analysis of Nepenthaceae. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2006;8:831–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osunkoya OO, Daud SD, Di-Giusto B, Wimmer FL, Holige TM. Construction costs and physico-chemical properties of the assimilatory organs of Nepenthes species in Northern Borneo. Ann Bot. 2007;99:895–906. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aung HH, Chia LS, Goh NK, Chia TF, Ahmed AA, Pare PW, et al. Phenolic constituents from the leaves of the carnivorous plant Nepenthes gracilis. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:445–7. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehanni MM, Safwat MS. Endophytes of Medicinal Plants. Acta Hort (ISHS) 2010;854:31–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhore SJ, Ravichantar N, Loh CY. Screening of endophytic bacteria isolated from leaves of Sambung Nyawa [Gynura procumbens (Lour.) Merr.] for cytokinin-like compounds. Bioinformation. 2010;5:191–7. doi: 10.6026/97320630005191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li L, Sinkko H, Montonen L, Wei G, Lindström K, Räsänen LA. Biogeography of symbiotic and other endophytic bacteria isolated from medicinal Glycyrrhiza species in China. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;79:46–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Zhao GZ, Huang HY, Qin S, Zhu WY, Zhao LX, et al. Isolation and characterization of culturable endophytic actinobacteria associated with Artemisia annua L. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2012;101:515–27. doi: 10.1007/s10482-011-9661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verstraete B, Van Elst D, Steyn H, Van Wyk B, Lemaire B, Smets E, et al. Endophytic bacteria in toxic South African plants: Identification, phylogeny and possible involvement in gousiekte. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West ER, Cother EJ, Steel CC, Ash GJ. The characterization and diversity of bacterial endophytes of grapevine. Can J Microbiol. 2010;56:209–16. doi: 10.1139/w10-004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaneko T, Minamisawa K, Isawa T, Nakatsukasa H, Mitsui H, Kawaharada Y, et al. Complete genomic structure of the cultivated rice endophyte Azospirillum sp. B510. DNA Res. 2010;17:37–50. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chelius MK, Triplett EW. The diversity of archaea and bacteria in association with the roots of Zea mays L. Microb Ecol. 2001;41:252–63. doi: 10.1007/s002480000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CH, Zhao MW, Tang CM, Li SP. Population dynamics and identification of endophytic bacteria antagonistic toward plant-pathogenic fungi in cotton root. Microb Ecol. 2010;59:344–56. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9570-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]