Abstract

The pathological foundation of human prion diseases is a result of the conversion of the physiological form of prion protein (PrPc) to the pathological protease resistance form PrPres. Most patients with prion disease have unknown reasons for this conversion and the subsequent development of a devastating neurodegenerative disorder. The conversion of PrPc to PrPres, with resultant propagation and accumulation results in neuronal death and amyloidogenesis. However, with increasing understanding of neurodegenerative processes it appears that protein-misfolding and subsequent propagation of these rouge proteins, is a generic phenomenon shared with diseases caused by tau, α-synucleins and β-amyloid proteins. Consequently, effective anti-prion agents may have wider implications. A number of therapeutic approaches include polyanionic, polycyclic drugs such as pentosan polysulfate (PPS), which prevent the conversion of PrPc to PrPres and might also sequester and down-regulate PrPres. Polyanionic compounds might also help to clear PrPres. Treatments aimed at the laminin receptor, which is an important accessory molecule in the conversion of PrPc to PrPres – neuroprotection, immunotherapy, siRNA and antisense approaches have provided some experimental promise.

Keywords: Prion diseases, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, treatments, neurodegenerative diseases, protein misfolding, protein propagation

Introduction

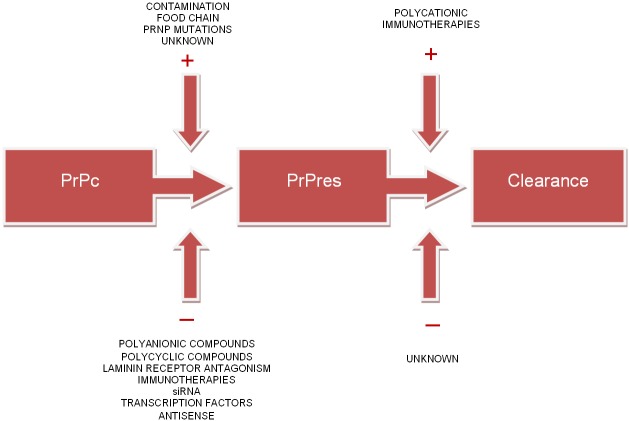

Prion disease is thought to arise from the transformation of normal host-encoded prion proteins (PrPc) to aberrantly folded protease resistant isoforms (PrPres) [1,2] (Figure 1). This abnormal prion propagation and accumulation throughout the central and peripheral nervous system results in an ultimately fatal neurodegenerative disease process characterised by rapidly progressive dementia [3]. Exposure to exogenous PrPres through contaminated biomaterials, the food chain (nv CJD) and mutations in the PrP gene have been identified as causative agents [4]. However, the aetiology of the majority of prion diseases in neurological practice is tragically sporadic with no cause ever identified. This devastating clinical scenario signals the need for the development of therapeutic strategies focused upon symptomatic management, prolongation of survival and ultimately reversal of neurodegenerative processes. This article reviews current therapeutic strategies and recent advances in the treatment of prion diseases.

Figure 1.

Therapeutic approaches to human prion diseases.

Therapeutic possibilities

The mechanisms involved in prion pathogenesis remain enigmatic [5] which has unfortunately hindered the development of effective therapeutic agents [2]. However it is evident that prions do not require nucleic acids or other cofactors to transmit disease [6,7] and clinical manifestations cannot ensue without the initial presence of PrPc [8]. However, the importance of understanding the role of PrPc transformation and accumulation is not only relevant to prion-mediated neurodegeneration.

Neurodegeneration caused by templated conformational change of proteins appears to be a generic mechanism of pathogenesis [9,10]. Several in vivo and in vitro findings have confirmed the role of mutant tau, amyloid-β and α-synuclein in the development of regional pathology and disease progression in Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementias and Parkinson’s disease [11,12]. The simultaneous existence of cellular dysfunction together with rouge protein propagation and accumulation are a feature of these disease patterns though do not equally impinge on the rate of neuronal death [9]. While transmissibility seems to be an exclusive feature of prion diseases [10], the generic process of regional neuronal destruction might mean that developing a therapeutic agent for prion disease may have wider-implications for other diseases [13].

The current foundations of therapeutic efforts centre upon the assumption that disease processes stem from the transformation of PrPc to PrPres and subsequent accumulation of this protease-resistant isomer [6]. Direct inhibition of this conversion, degradation of PrPres, interference with important accessory molecules (Fab, glycosaminoglycans) or altering PrPc expression and/or cell surface localisation remain important target strategies [5,14-16].

Laminin, a high affinity prion receptor (LPR/LR) may be a suitable medication target. Interestingly, it seems that LRP/LR acts as a receptor for both the cellular prion protein and the infectious PrPres [17] and might further play an essential role in PrPres binding and intracellular internalisation. Indeed it has been observed that siRNA against LRP mRNA inhibits PrPres accumulation in infected N2a neuroblastoma cells [18]. Resultantly, ligands targeting this receptor must be explored. Additional investigation into the contribution of lipid rafts, sphingolipid rich molecular carriages and the location of PrPc transformation present further therapeutic options.

Additional findings demonstrate the transcriptional activation of PrPc may result from the direct binding of p53 to the suspected promoter region [8]. The generation of Aβ oligomers via γ-secretase action in turn, activates p53. Understanding this complex interaction suggests the use of γ-secretase inhibitors as a strategy to not only modulate PrPc transcription, but also PrPres accumulation [8]. In fact Spilman et al [19] demonstrate a reduction of neocortical and hipppocampal PrPres accumulation in mice with the oral administration of γ-secretase inhibitors and quinacrine. However, the sole use of γ-secretase inhibitors in this study did not realise any therapeutic or pathological benefit.

Several studies have illustrated the role of tau proteins in exacerbating β-amyloid related cytotoxicity and neurodegeneration in dementia [20,21]. In fact, Nussbaum and colleagues [21] demonstrate that knocking out tau provided complete protection against neuronal loss and glial activation from toxic Aβ species in mice. Subsequently, these findings have provoked interest into the relevance of tau in prion and other neurodegenerative disease processes. Findings of in vivo and in vitro studies suggest that β-amyloid interacts with PrPc [22]; resulting in kinase activation and tau hyperphosphorylation [23]. More recently Chen et al [24] highlighted this interaction, demonstrating that PrPc over expression down-regulated tau protein at the transcriptional level whilst Aβ oligomer binding alleviated the induced tau reduction. Furthermore, subsequent treatment with Fyn pathway inhibitors reversed the PrPc-induced tau reduction; suggesting that the Fyn pathway may regulate Aβ-PrPc-tau signalling. Increases in total tau protein levels have been observed in advanced prion disease and were found to be a significantly superior disease marker when compared to the 14-3-3 protein in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD) [25].

Recent evidence also places focus upon α-synuclein; a major component of filamentous inclusions defining a large group of neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease, Lewy body dementia and multiple-system atrophy [12]. Lesions produced by α-synuclein spread progressively throughout the brain, correlating closely with clinical deficits experienced. Findings from several studies suggest that pathological α-synuclein may be transmissible [12,26]; demonstrating that the introduction of exogenous α-synuclein fibrils induces Lewy-body pathology in cultured neurons [27]. More recently, Masuda-Suzukake and colleagues [12] demonstrated that intracerebral injections of sarkosyl-insoluble α-synuclein from brains of patients with Lewy body dementia or recombinant α-synuclein from wild-type mice induce hyperphosphorylated α-synuclein pathology in vivo. Further biochemical analysis revealed the prion-like transformation of α-synuclein, with subsequent deposition and propagation throughout neuronal tissue [12].

Aside from medications, other theoretical possibilities for the treatment of prion diseases exist. There has been some experimental data to suggest the use of monoclonal antibodies against PrP for prophylaxis [5]. However, the in vivo stimulation of immune competent cells which recognise and neutralise abnormally folded prion isoforms needs to be investigated. Delivery systems using lentiviruses or adenoviruses with anti-prion components including antibodies, short-interfering micro RNAs or Antisense RNAs remain considerations.

Theraputic challenges

Investigating therapeutic possibilities for rare diseases can often provide valuable insights for more common conditions [13]. Neurodegeneration caused by the underlying mechanism of protein misfolding seems to be a truly generic phenomenon [9] and therefore identification of an anti-prion agent may have wider therapeutic applications and consequences. However, therapeutic progress is hampered by the scarcity of natural history and clinical progression data in addition to the lack of validated outcome measures [6,13]. Compiled with the heterogeneity of disease manifestation and the rapidity of deterioration experienced by patients, developing clinically and ethically adequate trial designs is challenging [13].

Early spongiform change and synapse loss often remains subclinical [28]. While the characteristics of a lesion resulting from α-synuclein and tau propagation often correlate well with clinical progression [12] the extent of prion-induced neuronal death may be difficult to detect clinically early. Subtle motor dysfunction leading to a patient’s initial presentation may result from quite advanced and irreversible neuronal cell death [28,29]. Coupled with a typically lengthy diagnostic and investigative period, the trajectory to irreversible neurodegeneration makes early treatment problematic. While current treatment options cannot provide reversal of symptoms or significant prolongation of survival, it is difficult to decipher whether these options are truly ineffective or are simply administered too late in the clinical course to offer any real benefit [28].

Establishing an accurate and early diagnosis may therefore be the key to therapeutic success and imperative to the continuation of research progression [13]. An accurate diagnosis is difficult to defend in the absence of acceptable criteria; and therefore, any research findings necessitate additional scrutiny when prion propagation may not be the cause of a patient’s neurodisability. The rapid progression of neurological deficits characteristic of prion disease places survival as the key outcome measure in current therapeutic trials [13]. However, this does not factor the molecular variability of differing subtypes of prion diseases [29], the clinical progression of the disease nor has the scope to capture the profound physical and cognitive impairments that many patients face [13,29].

Prophylactic treatment may be indicated in individuals susceptible to developing genetic prion disease. This subgroup could provide a rare opportunity to investigate the potential benefits of agents long before neuronal death has occurred whilst also offering the insight of longitudinal follow-up.

Therapeutic experiences

Pentosan polysulfate

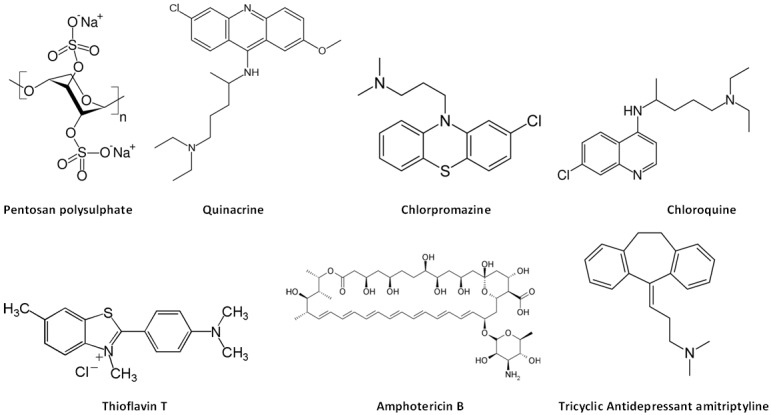

Pentosan polysulfate (PPS) is a large polyglycoside molecule, demonstrating weak heparin-like activity [30] (Figure 2). PPS is presumed to act in competition with endogenous heparin sulphate proteoglycans as co-receptors for PrP on the cell surface [31]. When directly administered into the cerebral ventricles of PrPres infected mice, PPS significantly prolongs the incubation period of early disease processes and inhibits the formation of PrPres in cell culture. Albeit promising, findings to date fail to illustrate any reversal of clinical manifestations or recovery of pre-existing neurological deficits in patients.

Figure 2.

Structure activity relationship of compounds used to treat human prion diseases: some of these agents share cyclic benzene ring structures with aliphatic side chains at middle ring moieties.

Administration of continuous intraventricular PSS infusion (1-120 μ/kg/day) was commenced in a 68 year old patient with sCJD 10 months following first symptomatic onset [32]. While the patient’s existing deficits did not improve, there was a noted stabilization in her neurological deterioration for four months (2 to 8 months following PSS infusion) and her survival of a total 27 months surpassed mean survival periods reported elsewhere in the literature. Parry et al [33] also described prolonged survival of 51 months in a 22 year-old male with vCJD using continuous intraventricular PPS at a dose of 32 mg/kg/day for 31 months.

Furthermore, a prospective study conducted by Tsuboi et al [30] showed a prolonged, mean survival time of 24.2 months in four patients following intraventricular PSS infusion (120 μ/kg/day). One patient is still alive six years after continuous infusion, though no major neurological improvement has been reported. Indeed given this extraordinary prolongation of life, the likelihood of prion pathology must be questioned.

The development of subdural effusions of variable degrees and intraventricular hematomas were common adverse effects [30,32].

Quinacrine

Quinacrine is an acridine derivative which has shown success in cellular models. Of interest, the drug has been shown to inhibit PrPres formation in scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells [34]; a function which is thought to arise from the inclusion of a nitrogen side chain to its quinoline ring [35]. Due to its use as an anti malarial drug, immediate trials in humans have been advocated [36] though in vivo findings are yet to identify any benefit to quinacrine treatment.

Furukawa et al [37] demonstrated a transient response in visual and auditory hallucinations in a small number of patients. Recovery of voluntary limb and pursuit eye movements were reported in a 37 year old female with CJD (secondary to a cadaveric dura matter graft) following administration of 300 mgs of quinacrine per day. The periodic sharp waves resolved. However, just two weeks after the onset of therapy the patient deteriorated and positive sharp waves reappeared [38].

A further four patients with sporadic CJD received 300 mgs of quinacrine; akinetic mutism improved within two weeks for one patient. The remaining patients were deemed “insensible” before treatment, though showed improvements in their interactive responses with eye contact, voluntary movement, and responses to verbal and visual stimuli after 1-2 months. Follow-up beyond two months was not provided [39]. Conversely a study conducted one year later revealed a slight but non-significant improvement with quinacrine use in 32 patients with sporadic CJD. No pathological evidence of benefit was observed [40].

Collinge and colleagues [41] illustrate that while 300 mgs per day of quinacrine was tolerated; it was not an effective therapeutic agent and did not influence the natural history of the disease. In fact, of the 107 participants with CJD included in this study only 26 survived and were suitable to be treated with quinacrine. The adjusted mortality was lower for the quinacrine treated group, but confounded by disease severity. After adjustment there was no difference. Four patients had a transient improvement in neurological scales; two had serious adverse side effects.

The therapeutic scope of quinacrine has possibly been hindered by a focus upon mono therapeutic approaches [42]. Synergistic anti-prion therapy has been trialled with Chlorpromazine, a phospholipase A2 inhibitor, which reduces inflammatory oxidative stress and may ease neurodegenerative processes [43]. Benito-Leon [44] treated two familial insomnia patients with quinacrine and chlorpromazine without benefit. In fact, the condition of the patients worsened. The same treatment course was trialled in a 54-year-old woman with a Heidenhain variant of prion disease and conversely, the patient remained stable and survived an additional 19 months [45]. Clinical improvement following six month treatment with quinacrine and chlorpromazine was also reported in a 46-year-old woman with iatrogenic CJD [46].

In vitro demonstration of cholesterol biosynthesis up-regulation following prion infection in various neuronal cells [47] has highlighted a possible association between prion infection and/or susceptibility with altered cholesterol homeostasis. Founded upon this notion, Orru and colleagues [48] demonstrated that the addition of cholesterol ester modulators (progesterone, pioglitazone, Verapamil and everolimus) to quinacrine and chlorpromazine, enhancing their anti-prion effects by reducing their EC50 10-fold. While the exact mechanism is poorly understood, such results warrant further investigation.

Thioflavine

Thioflavine is used in tissue stains as a means of identifying amyloidogenic proteins and is characterised by positive birefringence. Thioflavine and related chemicals can inhibit PrPres production [49]. Thioflavine has also been shown in vitro to inhibit PrPres formation along with Aβ 1-42 [50]. Thioflavine has also been shown to interfere with PrP185-288 aggregation and diminishing fibril assembly [51]. There is no human data on the effects of thioflavine in prion diseases.

Amphotericin B

In 1987 it was shown that amphotericin B, a macrolide polyene antibiotic, considerably delayed the incubation period in scrapie inoculated hamsters [52]. In 1992, Xi et al [53] showed that scrapie infected hamsters given amphotericin B had a delayed accumulation of PrPres by 30 days, without affecting scrapie replication. The hamsters treated with amphotericin B developed prion disease later than those untreated. Demaimay et al [54] showed that late treatment with amphotericin B prolonged the viable time of scrapie infected mice – between 80 and 140 days post inoculation with reduction in the accumulation of PrPres.

A synthetic derivative of amphotericin B was shown to prevent replication of the scrapie agent at the inoculation site. This site contained astrocytes, where the abnormal PrP was produced. Grigoriev et al [55] speculated that the lysosomal system could be a target of amphotericin B. In vitro studies have also shown that amphotericin B prevents the conversion of PrPc [alpha helical] to PrPres (pathological beta sheet formation) [56].

In 1992, two patients with CJD were unsuccessfully treated with amphotericin B. One, a 71-year-old-woman, was hospitalised 3 months after the onset of dementia. The amphotericin B was given by intravenous infusion, starting 5 days after admission with a dosage of 0.25-1 mg/g. The amphotericin B was administered 6 days a week and the maximum dose reached in 8 days. After 20 days of treatment the patient’s clinical situation worsened and she died. The second patient was a 50-year-old woman who was seen 5 months after the onset of CJD at which time she was bed-ridden with akinetic mutism and myoclonic jerking. The EEG revealed periodic triphasic complexes. Amphotericin B was started one week after admission and at the doses described above, with a maximum dosage achieved in 8 days. The treatment was continued 6 days a week by slow intravenous infusion. The patient’s condition deteriorated and she died 8 months after the onset of the disease. Amphotericin B had no neurological effects on both of these patients and did not prevent progression [57].

Tetracyclines

Tetracyclines interact with PrPsc, destabilizing the structure of amyloid fibrils and facilitating the proteinase K digestion of PrP peptides [58,59]. Tetracyclines appear to not only bind to PrP aggregates, but to other neurotoxic peptides inhibiting nerve and glial cell toxicity in addition to astroglial proliferation [58,59]. De Luigi and colleagues [42] conducted a series of landmark experiments to not only highlight the efficacy of tetracyclines in early disease; but to assess therapeutic benefit when administered in latent diseases stages. In the first experiment, Syrian hamsters were peripherally infected with a 263K scrapie inocula intramuscularly and received a single dose of 10 mg/kg of Doxycycline at the same infection site within one hour. This single dose significantly (p=0.031) increased the median survival by 64% (from 217 days in controls vs 355 days for treated). A single intracerebroventricular infusion of 25 μg / 20 μl of Doxycycline or Minocycline entrapped in liposomes, was administered 60 days following inoculation when 50% of animals showed initial symptoms of the disease. Even at this advanced stage of neurodegeneration, survival rates increased by 8.1% and 10% respectively.

While these results stem from observational data, it is clear that both compounds significantly delayed the onset of clinical signs and prolonged survival [58]; warranting further investigation. Furthermore, it is suggested that tetracyclines inhibit the pathogenic PrP misfolding and thus, reduces the infectivity of the propagating prion. The implications of these findings also suggest that this approach may extend to other neurodegenerative processes reliant on rogue protein misfolding [58]. The long-standing safety profile and success of tetracycline use within other areas of clinical practice further render this therapeutic approach as a hopeful candidate in future human-trials.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants, like Desipramine, are heterocyclic compounds Figure 2 which have been shown to abolish prion infectivity in cell culture [60] The anti-prion effect was related to the redistribution of cholesterol from the plasma membrane to the intracellular compartment. This leads to membrane destabilization. In this study there were ultra-structural changes in the endosomal compartment. When these authors synthesized a novel compound of quinacrine and desipramine (quinapyramine) it had a synergistic effect in preventing prion infectivity. Of interest, the anti-prion effects of desipramine, quinacrine, quinapyramine were synergistic with simvastatin, a HMG CoA reductase inhibitor.

There is no human data on the effects of tricyclic antidepressants on prion diseases. Caution must be exercised in the use of tricyclic antidepressants as a reversible toxic neurological syndrome resembling prion diseases has been described [61].

The study of Klingenstein et al [60] raise the possibility that future treatments of prion disease might involve a combination of drugs including a tricyclic, an acridine derivative like quinacrine, and a statin.

Lithium chloride

Used primarily to treat mania or bipolar affective disorder, lithium chloride has been found to induce autophagy, enhancing clearance of mutant huntingtin and α-synucleins [1]. Application of this principle to prion-infected neuronal and non-neuronal cells, demonstrated an intense reduction in PrPsc accumulation as a result of lithium induced autophagy. When combined with Rapamycin, the anti-prion effects of lithium chloride were further enhanced [1]. This synergistic combination was also observed in a Huntington’s disease fly model [62]. Further testing is required, but such findings further highlight the possible generic phenomenon of protein-based neuro degeneration.

Immunotherapies

In 2004 it was shown that humoral immune responses to native eukaryotic prion protein correlate with anti-prion protection [63]. The difficulty with immunological approaches to prion therapy is overcoming self tolerance to the physiological prion PrPc. In vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that antibodies to PrPc decrease or prevent the transformation to PrPres [64,65]. Active and passive immunisation might stimulate antibody induced phagocytosis, antibody disruption of peptide aggregates, mobilisation of toxic soluble peptides, stimulation of cell mediated immunity and other mechanisms [66].

Monovalent antibody fragments to various parts of the prion protein have been shown in vitro to prevent the oligomerization of the prion protein. These regions are: codons 90-110, the helix region codons 145-160, the extreme C-terminal codons 210-220 and the octarepeat region [67]. Sakaguchi and Arakawa [68] suggested that tolerance could be overcome by immunizing the PrP fused to bacterial enterotoxins or delivered using an attenuated Salmonella strain.

Campana et al [69] showed that brain delivery of prion specific proteins using single chain variable fragments with adeno-associated virus transfer delayed the onset of prion disease in infected mice. The single chain variable fragment of the PrP complex including Arg (PrP 151) linked to the adeno-associated virus was the key residue anchoring PrPc to the cavity of the antibody. Federoff [70] postulated that active immunisation can disrupt Aβ 1-42 formation in mice and passive immunisation of a recombinant adeno virus anti-prion can attenuate disease progression and prolong life in experimental models of prion diseases. This mounting body of experimental evidence will in the future lead to immunological trials of both active and passive immunisation in prion diseases as is being performed in Alzheimer’s disease. Full length antibodies do not cross the blood brain barrier.

Other possible therapies

Bellingham et al [71] have shown that prion gene expression is regulated by transcription factors SP1 and a metal transcription factor-1. The Menkes protein is a major copper efflux protein. Fibroblasts that have the Menkes deletion have an increase in copper levels. If the cells have Menkes protein over-expression, then copper is reduced. In the cell lines with low copper, cellular prion protein and mRNA level is reduced. siRNA knockouts of SP1 and MTF1 reduced prion PrP protein and gene expression in vitro suggesting that these transcription factors might be future targets for prion therapy.

The LRP/LR laminin receptor is a 37 kDa / 67 kDa that is important in cell adhesion, apoptosis, virus binding and prion binding function. This multi-faceted and multi-functional protein is found at the cell membrane, cytoplasm and nucleus. In vitro experiments blocking the LRP/LR receptor with antibodies, or siRNA agonists to LRP mRNA or LRP decoy mutants block or download the receptor and reduce prion infectivity. Of interest, PPS and other heparin-like moieties bind to this receptor [72].

Lentiviral vectors expressing small interfering siRNAs directed against the laminin receptor precursor mRNA prolonged the preclinical phase of scrapie infected mice [73]. Stereotactic intracerebral micro injection into the hippocampus with recombinant lentiviral vectors expressing siRNA to LRP7 and 9 were effective in prolonging the pre-clinical phase and modulating clinical disease in scrapie infected mice.

More experimental work on the exploration of transcription factors and the laminin receptor is required to justify human studies.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a free radical scavenger and recent experimental studies in a rodent model, using an agent with similar actions to SOD, extended the life of scrapie infected animals raising the possibility of a free radical and oxidative stress attack on prion diseases [74].

Conclusion

There are difficulties in developing new treatments for prion diseases. Double-blind randomised controlled trials with adequate power seem impossible. Current therapeutic experiences are based on small numbers of patients and having control subjects raise ethical difficulties in a disorder with a poor prognosis. Short survival time and variable natural history are an added difficulty for therapeutic studies. However, these limitations should not discourage the search for prion disease treatments.

Recent findings suggest a common thread of neurodegenerative pathogenesis involving misfolding of prion, tau, α-synuclein and β-amyloid proteins which, with increasing comprehension of these processes, might lead to generalised therapeutic modalities.

There is a need for prion disease biomarkers which might best indicate clinical responses to treatment. Predictive gene testing is possible and families with pre-manifest prion disease exist. Potential treatments are a possibility for these individuals, as currently conducted for inherited Alzheimer’s disease.

These limitations suggest that in the future an international collaboration might be necessary to pool therapeutic experiences and coordinate therapeutic studies similar to study groups in other disorders with small numbers of patients like the Huntington’s Study Group (HSG): a Prion Diseases Study Group (PSG)?

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Heiseke A, Aguib Y, Riemer C, Baier M, Schatzl HM. Lithium induces clearance of protease resistant prion protein in prion-infected cells by induction of autophagy. J Neurochem. 2009;109:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sim VL, Caughey B. Recent advances in prion chemotherapeutics. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:81–91. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moreno JA, Radford H, Peretti D, Steinert JR, Verity N, Guerra Martin MG, Halliday M, Morgan J, Dinsdale D, Ortori CA, Barrett DA, Tsaytler P, Bertolotti A, Willis AE, Bushell M, Mallucci GR. Sustained translational repression by elF2α-P mediates prion neurodegeneration. Nature. 2012;485:507–511. doi: 10.1038/nature11058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamguney G, Giles K, Glidden DV, Lessard P, Wille H, Tremblay P, Groth DF, Yehiely F, Korth C, Moore RC, Tatzelt J, Rubinstein E, Boucheix C, Yang X, Stanley P, Lisanti MP, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Moskovitz J, Epstein CJ, Cruz TD, Kuziel WA, Maeda N, Sap J, Ashe KH, Carlson GA, Tesseur I, Wyss-Coray T, Mucke L, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Genes contributing to prion pathogenesis. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:1777–1788. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krammer C, Vorberg I, Schatzl HM, Gilch S. Therapy in prion diseases: from molecular and cellular biology to therapeutic targets. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:3–14. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appleby BS, Lyketos CG. Rapidly progressive dementias and the treatment of human prion diseases. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1–12. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2010.514903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J, Cali I, Surewicz K, Kong Q, Raymond GJ, Atarashi R, Race B, Qing L, Gambetti P, Caughey B, Surewicz WK. Mammalian prions generated from bacterially expressed prion protein in the absence of any mammalian cofactors. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14083–14087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.113464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincent B, Sunyach C, Orzechowski HD, St George-Hyslop P, Checler F. P53 dependent transcriptional control of cellular prion by presenilins. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6752–6760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0789-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallucci G. Spreading proteins in neurodegeneration: where do they take us? Brain. 2013;136:994–997. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yi CW, Xu WC, Chen J, Liang Y. Recent progress in prion and prion-like protein aggregation. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2013;45:520–526. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yiannopoulou KG, Papageorgious SG. Current and future treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:19–33. doi: 10.1177/1756285612461679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda-Suzukake M, Nonaka T, Hosokawa M, Oikawa T, Arai T, Akiyama H, Mann DM, Hasegawa M. Prion like spreading of pathological α-synuclein in brain. Brain. 2013;136:1128–1138. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson AGB, Lowe J, Fox Z, Lukic A, Porter MC, Ford L, Gorham M, Gopalakrishnan GS, Rudge P, Walker AS, Collinge J, Mead S. The medical research council prion disease rating scale: a new outcome measure for prion disease therapeutic trials developed and validated using systematic observational studies. Brain. 2013;136:1116–1127. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appleby BS, Appleby KK, Onyike CU, Wallin MT. Initial diagnosis predicts survival time in human prion disease. Poster presentation in Madrid: Prion. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissmann C. Birth of a prion: spontaneous generation revisited. Cell. 2005;122:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuber C, Ludewigs H, Weiss S. Therapeutic approaches targeting the prion receptor LRP/LR. Vet Microbiol. 2007;123:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gauczynski S, Nikles D, El-Gogo S, Papy-Garcia D, Rey C, Alban S, Barritault D, Lasmezas CI, Weiss S. The 37-kDa/67-kDa laminin receptor acts as a receptor for infectious prions and is inhibited by polysulfated glycans. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:702–709. doi: 10.1086/505914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leucht C, Vana K, Renner-Muller I, Dormont D, Lasmezas CI, Wolf E, Weiss S. Knock-down of the 37-kDa laminin receptor in mouse brain by transgenic expression of specific antisense LRP RNA. Transgenic Res. 2004;13:81–85. doi: 10.1023/b:trag.0000017177.35197.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spilman O, Lessard P, Sattavat M, Bush C, Tousseyn T, Huang EJ, Giles K, Golde T, Das P, Fauq A, Prusiner SB, Dearmond SJ. A γ-secretase inhibitor and quinacrine reduce prions and prevent dendritic degeneration in murine brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10595–10600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803671105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King ME, Kan HM, Baas PW, Erisir A, Glabe CG, Bloom GS. Tau-dependent microtubule disassembly initiated by prefibrillar beta-amyloid. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:541–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nussbaum JM, Schilling S, Cynis H, Silva A, Swanson E, Wangsanut T, Tayler K, Wiltgen B, Hatami A, Rönicke R, Reymann K, Hutter-Paier B, Alexandru A, Jagla W, Graubner S, Glabe CG, Demuth HU, Bloom GS. Prion-like behaviour and tau-dependent cytotoxicity of pyroglutamylated amyloid-β. Nature. 2012;485:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westaway D, Jhamandas JH. The P’s and Q’s of cellular PrP-Aβ interactions. Prion. 2012;6:359–369. doi: 10.4161/pri.20675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larson M, Sherman MA, Amar F, Nuvolone M, Schneider JA, Bennett DA, Aguzzi A, Lesné SE. The complex PrP(c)-Fyn couples human oligomeric Aβ with pathological tau changes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16857–16871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1858-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen RJ, Chang WW, Lin YC, Cheng PL, Chen YR. Alzheimer’1(1):s amyloid-β oligomers rescue cellular prion protein induced tau reduction via the fyn pathway. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013 Jul 18; doi: 10.1021/cn400085q. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamlin C, Puoti G, Berri S, Sting E, Harris C, Cohen M, Spear C, Bizzi A, Debanne SM, Rowland DY. A comparison of tau and 14-3-3 protein in the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2012;79:547–552. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318263565f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller CM, de Vos RA, Maurage CA, Thal DR, Tolnay M, Braak H. Staging of sporadic Parkinson disease-related alpha-synuclein pathology: inter- and intra-rater reliability. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:623–628. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171652.40083.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rochenstein E, Crews L, Spencer B, Masliah E, Lee SJ. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha- synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13010–13015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White MD, Mallucci GR. RNAi for the treatment of prion disease: a window for intervention in neurodegeneration? CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8:342–352. doi: 10.2174/187152709789541934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zerr I. Therapeutic trials in human transmissible spongiform encephalopathies: recent advances and problems to address. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:92–99. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuboi Y, Doh-Ura K, Yamada T. Continuous intraventricular infusion of pentosan polysulfate: clinical trial against prion diseases. Neuropathology. 2009;29:632–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2009.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larramendy-Gozalo C, Barret A, Daudigeous E, Mathieu E, Antonangeli L, Riffet C, Petit E, Papy-Garcia D, Barritault D, Brown P, Deslys JP. Comparison of CR36, a new heparin mimetic, and pentosan polysulfate in the treatment of prion diseases. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1062–1067. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terada T, Tsuboi Y, Obi T, Doh-Ura K, Murayama S, Kitamoto T, Yamada T, Mizoguchi K. Less protease-resistant PrP in a patient with sporadic CJD treated with intraventricular pentosan polysulphate. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;121:127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parry A, Baker I, Stacey R, Wimalaratna S. Long term survival in a patient with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease treated with intraventricular pentosan polysulphate. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:733–734. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doh-ura K, Ishikawa K, Murakami-Kubo I, Sasaki K, Mohri S, Race R, Iwaki T. Treatment of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy by intraventricular drug infusion in animal models. J Virol. 2004;78:4999–5006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.4999-5006.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murakami-Kubo I, Doh-Ura K, Ishikawa K, Kawatake S, Sasaki K, Kira J, Ohta S, Iwaki T. Quinoline derivatives are therapeutic candidates for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J Virol. 2004;78:1281–1288. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1281-1288.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korth C, May BC, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB. Acridine and phenothiazine derivatives as pharmacotherapeutics for prion disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9836–9841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161274798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furukawa H, Takahashi M, Nakajima M, Yamada T. Prospects of the therapeutic approaches to Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a clinical trial of antimalarial, quinacrine. Nippon Rinsho. 2002;60:1649–1657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi Y, Hirata K, Tanaka H, Yamada T. Quinacrine administration to a patient with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease who received a cadaveric dura mater graft – an EEG evaluation. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2003;43:403–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima M, Yamada T, Kusuhara T, Furukawa H, Takahashi M, Yamauchi A, Kataoka Y. Results of quinacrine administration to patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:158–163. doi: 10.1159/000076350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haïk S, Brandel JP, Salomon D, Sazdovitch V, Delasnerie-Lauprêtre N, Laplanche JL, Faucheux BA, Soubrié C, Boher E, Belorgey C, Hauw JJ, Alpérovitch A. Compassionate use of quinacrine in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fails to show significant effects. Neurology. 2004;63:2413–2415. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000148596.15681.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collinge J, Gorham M, Hudson F, Kennedy A, Keogh G, Pal S, ssor M, Rudge P, Siddique D, Spyer M, Thomas D, Walker S, Webb T, Wroe S, Darbyshire J. Safety and efficacy of quinacrine in human prion disease (PRION-1 study): a patient- preference trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:334–344. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70049-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Luigi A, Colombo L, Diomede L, Capobianco R, Mangieri M, Miccolo C, Limido L, Forloni G, Tagliavini F, Salmona M. The efficacy of tetracyclines in peripheral and intracerebral prion infection. PLoS One. 2008;26:e1888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farooqui AA, Ong WY, Horrocks LA. Inhibitors of brain phospholipase A2 activity: their neuropharmacological effects and therapeutic importance for the treatment of neurologic disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:591–620. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benito-Leon J. Combined quinacrine and chlorpromazine therapy in fatal familial insomnia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2004;27:201–203. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000134853.36429.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arruda WO, Bordignon KC, Milano JB, Ramina R. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Heidenhain variant: case report with MRI (DWI) findings. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2004;62:347–352. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2004000200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martínez-Lage JF, Rábano A, Bermejo J, Martínez Pérez M, Guerrero MC, Contreras MA, Lunar A. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease acquired via a dural graft: failure of therapy with quinacrine and chlorpromazine. Surg Neurol. 2005;64:542–545. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bach C, Glich S, Rost R, Greenwood AD, Horsch M, Hajj GN, Brodesser S, Facius A, Schädler S, Sandhoff K, Beckers J, Leib-Mösch C, Schätzl HM, Vorberg I. Prion-induced activation of cholesterogenic gene expression by Srebp2 in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31260–31269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orru CD, Doloewa Cannas M, Vascellari S, Angius F, Cocco PL, Norfo C, Mandas A, La Colla P, Diaz G, Dessi S, Pani A. In vitro synergistic anti-prion effect of cholesterol ester modulators in combination with chlorpromazine and quinacrine. Cent Eur J Biol. 2010;5:151–165. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doh-ura K. Therapeutics for prion diseases. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2003;43:820–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boshuizen RS, Langeveld JP, Salmona M, Williams A, Meloen RH, Langedijk JP. An in vitro screening assay based on synthetic prion protein peptides for identification of fibril-interfering compounds. Analytical Biochem. 2004;333:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klajnert B, Cortijo-Arellano M, Cladera J, Majoral JP, Caminade AM, Bryszewska M. Influence of phosphorus dendrimers on the aggregation of the prion peptide PrP 185-208. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2007;364:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pocchiari M, Schmittinger S, Masullo C. Amphotericin B delays the incubation period of scrapie in intracerebrally inoculated hamsters. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:219–223. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xi YG, Ingrosso L, Ladogana A, Masullo C, Pocchiari M. Amphotericin B treatment dissociates in vivo replication of the scrapie agent from PrP accumulation. Nature. 1992;356:598–601. doi: 10.1038/356598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Demaimay R, Adjou KT, Beringue V, Demart S, Lasmézas CI, Deslys JP, Seman M, Dormont D. Late treatment with polyene antibiotics can prolong the survival time of scrapie-infected animals. J Virol. 1997;71:9685–9689. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9685-9689.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Grigoriev VB, Adjou KT, Salès N, Simoneau S, Deslys JP, Seman M, Dormont D, Fournier JG. Effects of the polyene antibiotic derivative MS-8209 on the astrocyte lysosomal system of scrapie-infected hamsters. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;18:271–181. doi: 10.1385/JMN:18:3:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartsel SC, Weiland TR. Amphotericin B binds to amyloid fibrils and delays their formation: a therapeutic mechanism? Biochemistry. 2003;42:6228–6233. doi: 10.1021/bi0270384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masullo C, Macchi G, Xi YG, Pocchiari M. Failure to ameliorate Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with amphotericin B therapy. J Infectious Dis. 1992;165:784–785. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.4.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forloni G, Salmona M, Marcon G, Tagliavini F. Tetracyclines and prion infectivity. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:23–30. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tagliavini F, Forloni G, Colombo L, Rossi G, Girola L, Canciani B, Angeretti N, Giampaolo L, Peressini E, Awan T, De Gioia L, Ragg E, Bugiani O, Salmona M. Tetracycline affects abnormal properties of synthetic PrP peptides and PrP(Sc) in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1309–1322. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klingenstein R, Löber S, Kujala P, Godsave S, Leliveld SR, Gmeiner P, Peters PJ, Korth C. Tricyclic antidepressants, quinacrine and a novel, synthetic chimera thereof clear prions by destabilizing detergent-resistant membrane compartments. J Neurochem. 2006;98:748–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finelli PF. Drug-induced Creutzfeldt-Jakob like syndrome. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1992;17:103–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sarkar S, Rubinsztein DC. Small molecule enhancers of autophagy for neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:895–901. doi: 10.1039/b804606a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polymenidou M, Heppner FL, Pellicioli EC, Urich E, Miele G, Braun N, Wopfner F, Schätzl HM, Becher B, Aguzzi A. Humoral immune response to native eukaryotic prion protein correlates with anti-prion protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14670–14676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404772101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Griffin JK, Cashman NR. Progress in prion vaccines and immunotherapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:97–110. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buchholz CJ, Bach P, Nikles D, Kalinke U. Prion protein-specific antibodies for therapeutic intervention of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:293–300. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brody DL, Holtzman DM. Active and passive immunotherapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:175–193. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Müller-Schiffmann A, Korth C. Vaccine approaches to prevent and treat prion infection: progress and challenges. BioDrugs. 2008;22:45–52. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sakaguchi S, Arakawa T. Recent developments in mucosal vaccines against prion diseases. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:75–85. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Campana V, Zentilin L, Mirabile I, Kranjc A, Casanova P, Giacca M, Prusiner SB, Legname G, Zurzolo C. Development of antibody fragments for immunotherapy of prion diseases. Biochem J. 2009;418:507–515. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Federoff HJ. Development of vaccination approaches for the treatment of neurological diseases. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515:4–14. doi: 10.1002/cne.22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bellingham SA, Coleman LA, Masters CL, Camakaris J, Hill AF. Regulation of prion gene expression by transcription factors SP1 and metal transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1291–1301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804755200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vana K, Zuber C, Pflanz H, Kolodziejczak D, Zemora G, Bergmann AK, Weiss S. LRP/LR as an alternative promising target in therapy of prion diseases, Alzheimer’s disease and cancer. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9:69–80. doi: 10.2174/1871526510909010069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pflanz H, Vana K, Mitteregger G, Pace C, Messow D, Sedlaczek C, Nikles D, Kretzschmar HA, Weiss SF. Microinjection of lentiviral vectors expressing small interfering RNAs directed against laminin receptor precursor mRNA prolongs the pre-clinical phase in scrapie-infected mice. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:269–274. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.004168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brazier MW, Doctrow SR, Masters CL, Collins SJ. A manganese-superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic extends survival in a mouse model of human prion disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]