Abstract

Understanding the forces underpinning female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is a necessary first step to prevent the continuation of a practice that is associated with health complications and human rights violations. To this end, a systematic review of 21 studies was conducted. Based on this review, the authors reveal six key factors that underpin FGM/C: cultural tradition, sexual morals, marriageability, religion, health benefits, and male sexual enjoyment. There were four key factors perceived to hinder FGM/C: health consequences, it is not a religious requirement, it is illegal, and the host society discourse rejects FGM/C. The results show that FGM/C appears to be a tradition in transition.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2008) classification describes four types of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): clitoridectomy, excision, infibulations, and other. Despite considerable variation in extent of genital tissue removed, instruments used, age at which it is performed, and terminology of the practice, common to all forms of FGM/C is that it involves “the partial or total removal of the female external genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons” (WHO, 1997). It is widely recognized that the practice violates a series of human rights principles—including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child (WHO, 2008)—and causes permanent, often detrimental, changes in the external female genitalia, such as chronic pain, infections, and difficulty in passing urine and feces (see, e.g., WHO, 2000, 2008; WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome, 2006).

FGM/C is primarily practiced among various ethnic groups in more than 28 countries in Africa. Recent national figures show that nine out of 10 women and girls in Djibouti, Egypt, Guinea, Mali, Northern Sudan, Sierra Leone, and Somalia undergo the procedure (Yoder & Khan, 2008). The practice is also found in some countries in the Middle East and Asia (UNICEF, 2005a; WHO, 2006), however, and, although limited data exist, among immigrant communities in a number of Western countries, such as Australia, Canada, France, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States (WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome, 2006). It is further believed that the majority of girls living in Western countries who are subjected to FGM/C do not undergo the procedure in these countries. Instead, they are sent to their country of origin, usually in Africa, in order to undergo the practice (Elgaali, Strevens, & Mårdh, 2005; Kaplan-Marcusan, Torán-Monserrat, Moreno-Navarro, Fàbregas, Muñoz-Ortiz, 2009; Poldermans, 2006). For example, in a study of FGM/C among immigrants from northern Africa with current residency in Scandinavia, 73 out of 220 women interviewed reported being genitally cut during a return visit to their home country. Additionally, 15 of the women explained that they had their daughter clitoridectomized while living in Scandinavia (Elgaali et al., 2005). Similar data confirming that FGM/C takes place in Western countries have been reported by others (Chalmers & Hashi, 2002; Litorp, Franck, & Almroth, 2008; Morison, Dirir, Elmi, Warsame, & Dirir, 2004; Thierfelder, Tanner, & Bodiang, 2005).

As Western governments have become more aware of FGM/C among some immigrant communities, legislation has been implemented as the main intervention tool (European Parliament, 2004; Leye et al., 2007). Sweden was the first country to introduce a specific law prohibiting FGM/C in Europe, the 1982 Act Prohibiting Female Genital Mutilation (Leye & Sabbe, 2009). Now, there are laws prohibiting FGM/C in most Western countries (UNICEF, 2005a; WHO Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome, 2006). In Europe, about 45 criminal court cases on grounds of suspected FGM/C have been tried, and almost as many convictions obtained (Leye & Sabbe, 2009). Although responses to preventing the practice of FGM/C in Western countries primarily consist of prosecution, some countries—such as Austria, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom—give priority to prevention strategies, including awareness raising and empowerment of women (Poldermans, 2006).

To achieve success in preventing the continuation of FGM/C, it is necessary to understand the forces underpinning the practice, such that information, messages, and activities can be tailored to their audiences accordingly. Programs can aim to modify or remove factors perpetuating the practice and use or build upon existing factors that are seen to hinder the continuation of the practice. To this end, a systematic review identifying factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C was conducted. This article is based on and an update of a report (Berg, Denison & Fretheim, 2010) and results are presented regarding factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C, as expressed by members of communities practicing FGM/C residing in a Western country. Research on the perspectives of exile communities is particularly useful, because it is often the case that in the diaspora, members of communities where FGM/C is practiced more readily reflect upon, question, and challenge their home cultural models and values (Johansen, 2006). Thus, they may be uniquely able to identify the beliefs, values, and codes of conduct that influence the practice of FGM/C. Johansen (2006) writes: “Research in an exile community can help cast new light on cultural processes that were less accessible in the home context, because in exile they are voiced and debated to a higher extent” (p. 275).

METHODOLOGY

A literature search was performed up to March 2011 in 13 international databases: African Index Medicus, Anthropology Plus, British Nursing Index and Archive, The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, EPOC, MEDLINE, PILOTS, POPLINE, PsycINFO, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, and WHOLIS. It was supplemented with searches of the databases of six international organizations that are engaged in projects regarding FGM/C, the reference lists of relevant reviews and included studies, and communication with experts involved in FGM/C-related work.

Study designs eligible for inclusion were cross-sectional quantitative studies, qualitative studies, and mixed-methods studies. The population considered in scope was members of communities practicing FGM/C residing in a Western country, defined as a country with a culture of European origin (Huntington, 1996). The outcome of interest was the practice of FGM/C; specifically, the studies had to describe participants’ perspectives and understandings of the factors perpetuating or hindering the continuation of FGM/C. All publication years and languages were acceptable and when considered likely to meet the inclusion criteria, studies were translated to English. Unpublished reports and brief and preliminary reports were considered for inclusion on the same basis as published articles.

The processes of literature screening, assessment of methodological quality, and data extraction were first done independently by two reviewers. A final decision was agreed upon after discussing whether there was a discrepancy between the two reviewers. For all processes, differences in opinion were few and were resolved through rereading the publications and consensus. In selecting literature, the reviewers read all titles, abstracts, or both resulting from the search process and obtained full text copies of studies considered relevant. Next, they read the full texts and determined whether they met all inclusion criteria. Predesigned inclusion forms were used for each screening level.

To assess the quality of included studies, the checklist for cross-sectional quantitative studies (NOKC) and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) appraisal tool for qualitative research (www.sph.nhs.uk/what-we-do/public-health-workforce/resources/critical-appraisals-skills-programme) were used. For mixed-methods studies, both the qualitative component and the quantitative component of the study were subjected to quality appraisal, using the aforementioned tools.

Data from the full texts were extracted using a predesigned data recording form. Extracted data pertained to study and participant characteristics and descriptive data of factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C. For the qualitative research papers, study findings were defined to be all of the text considered results or findings in the publications, whether interpretations made by the authors or statements by the participants (Sandelowski & Barrows, 2003; Thomas & Harden, 2008). All findings—in the form of sentences, phrases, or text units dealing with factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C—were copied verbatim onto the data extraction form.

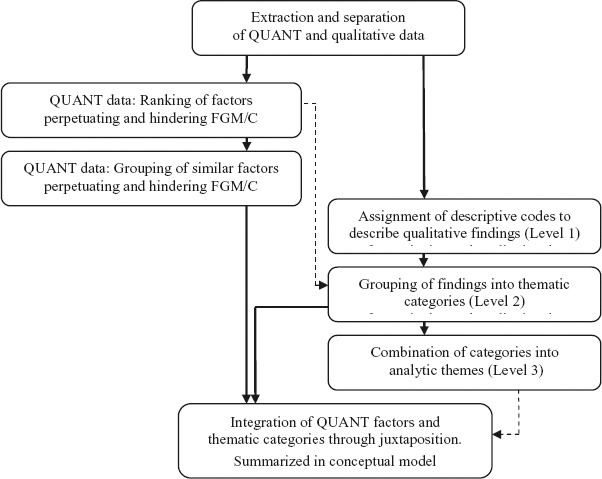

In recognition that the analysis method needs to be appropriate to the aim of the evidence synthesis, the systematic review utilized an integrative evidence approach (Figure 1). The approach was largely based on published examples and guidelines from the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI Centre; see, e.g., Harden et al., 2004; Shepherd et al., 2006). Briefly, data from cross-sectional survey studies were combined with data from studies that examined participants’ perspectives of factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C. The synthesis was aggregative (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006) and focused on summarizing data by pooling conceptually similar data from the quantitative studies and the qualitative “views” studies. First, a synthesis within study types was performed and then a synthesis between study types. Throughout the analysis, the quantitative results were used as the analytic point of departure (shown through capitalization in Figure 1), such that the qualitative results were subsumed under the quantitative results and were used to extend the results from the quantitative analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Integrative evidence approach.

With respect to the quantitative analysis, the results from each study were categorized according to whether the factors were perpetuating (continuance) or hindering (discontinuance) factors of FGM/C. The reviewers then calculated the frequencies of these factors in order to create a ranked list of factors. In the next step, similar factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C were grouped, to facilitate the integration of quantitative factors and thematic categories from the qualitative evidence. The grouping was based on commonality of meaning.

The analysis of qualitative evidence was thematic; that is, the reviewers identified prominent or recurring themes in the literature and summarized the findings of the different studies under thematic headings (Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005). They organized and assigned descriptive codes to the raw data from each study (Level 1 findings). Next, findings were grouped into thematic categories, based on commonality of meaning as well as frequency and strength of participants’ cognitions about FGM/C, thereby developing broader concepts that captured similar themes from different papers (Level 2 findings). Given that the quantitative evidence served as the analytic point of departure, the reviewers worked by using both a priori codes developed from the included quantitative studies to seek out evidence from the qualitative findings, as well as allowing themes to emerge from the qualitative data. In the last qualitative analysis step, categories were combined to create synthesized themes (Level 3 findings). This involved reflecting on the thematic categories as a whole and looking for similarities and differences among the categories. The analyses were first conducted individually, and then the reviewers, through discussion and reflection, agreed on a set of categories and analytic themes.

In the last analysis step, once both the quantitative and qualitative sets of data were analyzed, they were integrated. The integration involved creating a matrix in which the list of quantitative factors and thematic categories were juxtaposed. The juxtaposition of findings allowed examination of factors and themes that had been investigated, and factors and thematic categories for which there were more credible evidence due to convergence and corroboration. The analytic themes from the last qualitative synthesis were used as a thematic guide. The accumulation of the analyses and the conclusions were summed in a conceptual model that linked the factors and concepts together and delineated the underlying forces perpetuating and halting the practice. Further details about the methods and findings are described in Berg and colleagues (2010).

RESULTS

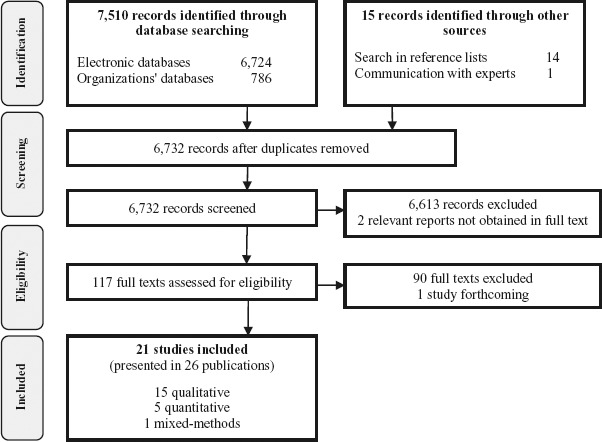

The searches resulted in 6,732 individual records (Figure 2). Two records could not be obtained in full text (Black Women's Health and Family Support Group, 1994; Sy, 1993) and one study is forthcoming (Kaplan-Marcusan et al., 2010). The reviewers read 117 full texts and included 21 studies, 15 of which were qualitative investigations, five were quantitative cross-sectional studies, and one was a mixed-methods study (Table 1). There were two dissertations (Gali, 1997; Khaja, 2004), three studies were reports submitted to funding agencies (Mwangi-Powell, 1999, 2001; Norman, Hemmings, Hussein, & Otoo-Oyortey, 2009), and the remaining studies were published in peer-reviewed journals. Application of the checklists showed that nine of the studies had low methodological quality, six moderate, and five high methodological quality. The qualitative and quantitative components of the mixed-methods study were assessed separately, and these were judged as high and moderate, respectively. All quantitative studies lacked documentation about whether the measures were reliable and valid, and most of them failed to explain whether the sample was representative of the population. Concerning the qualitative studies, several of them failed adequately to describe consideration of the relationship between the researcher and participants, ethical issues, and rigor of data analysis.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature reviewing process.

TABLE 1.

Description of Included Studies (N = 21)

| Author, year | Study type | Method, study quality | Population and setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ahlberg et al., 2004 | Qual. | Moderate | N = 110 (60 female). In Sweden. From Somalia. |

| Allag et al., 2001 | Qual. | Low | N = 14 females. In France. From Ethiopia, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal. Lived in France mean 9 yrs. 71% Muslim, 29% Christian. 100% FGM/C. |

| Berggren et al., 2006 | Qual. | High | N = 21 females. In Sweden. From Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan. Lived in Sweden med 7 yrs. Med age 35. 90% Muslim, 10% Christian. 100% FGM/C. |

| Chalmers & Hashi, 2000 | Quant. | Low | N = 432 females. In Canada. From: Somalia. 100% FGM/C. |

| Elgaali et al., 2005 | Quant. | Moderate | N = 315 (220 females and 95 husbands). In Scandinavia. From Northern Africa. Med age of women 21. 100% FGM/C. |

| Gali, 1997 | Qual. | Low | N = 50 females. In USA. From Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan. First generation or recent immigrant. Age 21–45. 62% Muslim, 36% Christian. |

| Gilette-Frenoy, 1992 | Qual. | Low | N = 41 (25 female). In France. From Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivre, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Zaire. |

| Guerin et al, 2006 | Qual. | Moderate | N = 64 females. In New Zealand. From Somalia. Age 27–48. 100% FGM/C. |

| Johansen, 20071 | Qual. | High | N = 70 (45 female). In Norway. From Somalia. Lived in Norway 1–7 yrs. Age 18–60. Most Muslim. Most infibulated. |

| Johnsdotter, 20092 | Qual. | Moderate | N = 33 female Ethiopians and male Eritreans living in Sweden. Most lived in West since 1980s. Age 28–69. Most Muslim. |

| Johnsdotter, 2003 | Qual. | Moderate | About 30 female and male Somalis living in Sweden. |

| Khaja, 20043 | Qual. | High | N = 17 females. In USA, Canada. From Somalia. Lived in USA or Canada mean 10 yrs. Mean age 41. Most Muslim. 100% FGM/C. |

| Litorp et al., 2008 | Quant. | Low | N = 40 females. In Sweden. From Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Kenya, Somalia. Mean age arrival in Sweden 21. Mean age 32. 80% Muslim, 20% Christian. 93% FGM/C. |

| Lundberg &, Gerezgiher 2008 | Qual. | High | N = 15 females. In Sweden. From Eritrea. Lived in Sweden 10–22 yrs. Age 31–45. 87% Muslim, 13% Christian. 100% FGM/C. |

| Morison et al., 2004 | Mixed-methods | Highmoderate | N = 174 (94 female). In England. From Somalia. Mean yrs duration in UK 14. Mean age 18. 83% Muslim. 70% FGM/C. |

| Morris, 1996 | Qual. | Low | Sample size not reported. Female Somalis living in USA. 100% FGM/C. |

| Mwangi-Powell, 1999 | Quant. | Low | N = 15 females. In England. From Somalia. Age 20–65. 100% FGM/C. |

| Mwangi-Powell, 2001 | Quant. | Low | N = 85 (42 female). In England. From Somalia (48%), Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Emirates. Age 15–66. 85% Muslim, 10% Christian. 95% FGM/C. |

| Norman et al., 2009 | Qual. | High | N = 30 females. In England. From Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan. Age 25 and older. |

| Upvall et al., 2009 | Qual. | Moderate | N = 23 females. In USA. From Somalia. Lived in the USA 11–27 months. Med age 33. Most Muslim. 100% FGM/C. |

| Vissandjée et al., 2003 | Qual. | Low | N = 162 (96 female). In Canada. From 23 African countries. |

Legend: Med = median; Method. = Methodological; yrs = years; Qual. = Qualitative; Quant. = Quantitative. 1Adjunct publication for the study is Johansen (2006); 2Adjunct publications for the study are Johnsdotter (2002) and Johnsdotter (2007); Adjunct publications for the study are Khaja et al. (2009; 2010).

In total, the studies included 1,741 participants (Morris [1996] did not report the number of participants in the study), of which 78% were women (Table 1). The participants were mostly from northern Africa and the horn of Africa, especially Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan. Currently, the majority of the participants resided in either Scandinavia (N = 634) or Canada (N = 603), while the remaining reported residency in England, France, New Zealand, or the United States. Duration of residency in the West varied, but, across the 10 studies reporting duration of residency in Western countries, it was about 10 years. Most participants appeared to have been in their thirties or forties at the time of the study, and most considered themselves Muslim. All but a few of the women had been subjected to FGM/C, typically infibulation.

Factors Perpetuating and Halting FGM/C

Quantitative data. Across the five quantitative studies, the range of similar reasons perpetuating and hindering FGM/C were grouped. Grouped factors perpetuating FGM/C follow: religion, tradition, marriageability, sexual morals, health benefits, male preference, aesthetics, and social pressure. Factors hindering FGM/C included the following: negative health issues, negative personal experiences, illegal, there's no need to do it, not religious requirement, it's not natural, and husband is against it. There were no studies that investigated only men's perspectives, but two studies specified views of men separately from women's: Men expressed a preference for a circumcised wife, but some said they did not view FGM/C as a religious requirement and some that they did not think that uncircumcised women were promiscuous.

Qualitative data. There were 15 qualitative studies and one mixed-methods study with a qualitative component. No qualitative studies examined only men's perspectives; thus men's views were incorporated with women's views. From the thematic categories, a set of eight analytic themes was produced that most parsimoniously and accurately captured the content and meaning of all the findings. First, in almost all studies, FGM/C was mentioned as a highly meaningful and valued cultural tradition. For example, “This is our tradition, it's something we should do” a participant in Johnsdotter (2009, p. 129) said. In almost all studies, the participants described enforcement of the norm through community mechanisms, explaining, “There are several social pressures and everyone has a say with regards to circumcising, especially from family and friends and the society as a whole” (Norman et al., 2009, p. 25). Nonetheless, due to exposure to Western thought models, migration allowed the participants to question doxic cultural models, including those of FGM/C, a reassessment that helped slow the continuation of the practice: Participants in Berggren and colleagues’ study (2006) explained, “Because of migration, they got rid of most of the female peer pressure to continue all forms of FGC” (p. 55). The two closely linked analytic themes of sexual morality and marriage were crucial as facilitators of FGM/C. In almost all studies, participants reasoned that FGM/C decreased women's sexual desires (“An uncut woman will run after men and have sex with anyone,” said a participant in Johansen [2007, p. 248]), thus protecting virginity, which was in many communities seen as prerequisite for marriage: “People perform FGC to reduce a girl's sexual desire to preserve her virginity before marriage” (Berggren et al., 2006, p. 55).

Another analytic theme was religion. According to Khaja's findings (2004), all but two of the life history interviewees cited religion as a main reason for FGM/C, viewing it as a practice honoring their Muslim faith. One participant said, “A girl who is not excised is considered as a bad Muslim” (Allag, Abboud, Mansour, Zanardi, & Quéreux, 2001, p. 2). Conversely, religion appeared also as a factor slowing the continuation of FGM/C in that many saw it merely as a religious option, or even in violation of Islam: “The most important reason for the women involved in our study for being opposed to pharaonic circumcision is that they are convinced that pharaonic circumcision is contrary to basic Islamic principles,” Johnsdotter (2003, p. 99) concluded.

A fifth analytic theme was hygiene. FGM/C was seen as ensuring the hygiene of the genitals, which in their natural form were classified as unclean. Asked what they thought to be the reasons behind the practice of FGM/C, one woman replied: “Some say that the girl who is not circumcised has a bad odour because she is not clean down there” (Norman et al., 2009, p. 23). A last analytic theme looking specifically at the continuance factors was that some perceived womanhood to be accomplished or activated through FGM/C: “As long as she hasn't been through it [excision] she hasn't become a woman” (Vissandjée, Kantiébo, Levine, & N'dejuru, 2003, p. 118).

Factors hindering the practice constituted two additional analytic themes, most prominently negative consequences of FGM/C, particularly their loss of sexual pleasure. The health consequences were wideranging, as explained by one woman in Norman and colleagues (2009): “Harmful effects and complications arise from circumcision, especially the pharaonic type, which has a lot of complications—emotional, physical, and health problems. A woman suffers those complications throughout her life” (p. 24). And “Sexual intercourse was hard, painful, especially the first few months” (Khaja, 2004, p. 113). “You know, circumcision affects your sexual life. I feel less. I feel I miss something” explained a third (Johansen, 2007, p. 268). Some women who themselves had experienced complications following FGM/C did not want to expose their daughters to such risks: “I don't want my daughter to pass through all the pain and suffering that I had” stated one woman in Lundberg and Gerezgiher (2008, p. 221). The unlawful practice of FGM/C emerged as a last analytic theme. It was clear in many of the studies that most exiled communities respected Western countries’ laws against the practice. Researchers such as Berggren and colleagues (2006) found that “Almost all women explained how they perceived the Swedish law as supporting them in their decision to protect their daughters from FGC” (p. 55). Without forming consistent themes, a few additional factors signaled beliefs perpetuating and countering FGM/C, including the following beliefs: FGM/C enhances sexual pleasure (generally for men), being cut is a sign of honor, and the clitoris is dangerous (kleitorid dangereux).

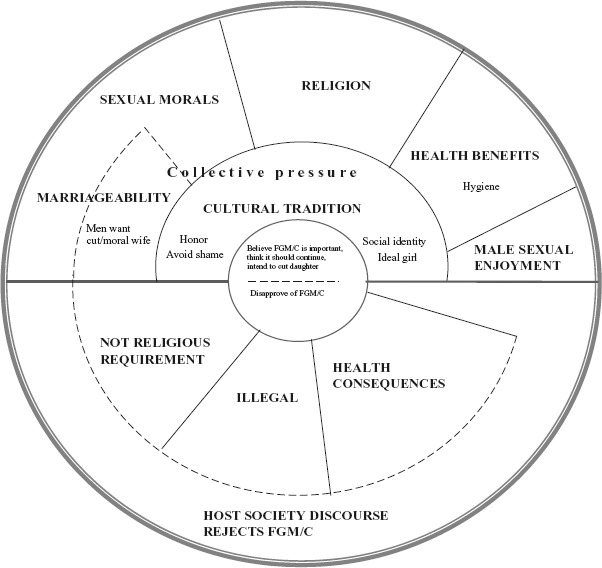

Integration of data. In the last analysis step, quantitative and qualitative data integration identified six key factors perpetuating and four key factors hindering the practice of FGM/C. A conceptual model summarizes the findings (Figure 3), showing the most dominant factors, those with more and credible data through convergence and corroboration (marked through capitalization), perpetuating and hindering the continuation of FGM/C. The center represents any member of a practicing community presently residing in a Western country, exposed to myriad influences regarding FGM/C. Porous lines signal that factors are related.

FIGURE 3.

Conceptual model of factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C.

Key drivers perpetuating FGM/C are presented in the upper half of the model, with the most influential factor, cultural tradition, most proximal to the center because there were more data for this factor than the other five key factors situated more distally. When asked why FGM/C is performed, in almost all studies, the participants considered it a meaningful cultural tradition, which functioned both as a form of social control and identity for women, as well as a feature of the ideal girl. It was deeply rooted in their social systems, and the compulsory nature of the practice reflected in community mechanisms enforcing it. Extensive collective enforcement of the tradition was strongly linked with honor and avoidance of shame, not just for the girl but also the mother and sometimes the extended family.

The second key factor, sexual morals, reflected the common view that FGM/C is a cornerstone of moral virtue. FGM/C, especially infibulation, was believed to reduce sexual lust, which was seen as easily aroused and difficult to control thus likely to lead the uncut woman to sexual promiscuity. Together with FGM/C, premarital chastity and marital fidelity were seen to function as proof of morality, granting the woman social respect. Related, the factor marriageability was frequently found in both the quantitative and qualitative data sets and converged to a significant extent with sexual morals in that premarital virginity served as a guarantee of moral standards. FGM/C in childhood or young adulthood was considered a prerequisite for good marriage later in life. Quantitative results showed that men strongly favored a future wife to have FGM/C, and findings from qualitative data indicated that the partiality concerned preference for a moral, faithful wife.

As a fourth important factor influencing the continuation of FGM/C, the practice was commonly expressed as a duty according to the religion of Islam. Respondents from countries where FGM/C is traditionally performed believed that FGM/C is sanctioned by Islamic religion. Individuals who did not conform to the practice were considered to be acting against their religion and the Qur'an.

Two additional, less influential factors reported in the included studies were health benefits and male sexual enjoyment. Health benefits referred to cleanliness and hygiene. The perception that men preferred cut women for their sexual enjoyment was mentioned both in some quantitative and qualitative studies, perpetuating the view among women that men favored women who had been subjected to FGM/C, specifically infibulation, because they gained greater sexual pleasure from a tight vagina. This idea was disputed by men quoted in the qualitative studies.

The lower half of the model shows the four key factors identified as hindering the practice of FGM/C. This model area offers a negated reflection of the top area in that three factors perpetuating FGM/C are similarly found to hinder FGM/C, thus demonstrating that FGM/C among exiled communities is a tradition in transition. One factor hindering FGM/C, health issues, was mentioned most prominently in the data sets. The participants were conscious of the harmful consequences following FGM/C, mentioning pain and women's reduced sexual responsiveness in particular. There was also strong convergence between quantitative and qualitative findings concerning the second and third factors hindering FGM/C. First, most participants knew the illegal status of FGM/C in their Western host countries. The law was not just a deterrent but for many was also a support in their decision to abandon FGM/C. Second, many participants stated that FGM/C was not an Islamic duty and put this forth as an important reason why they would not follow the tradition. The last key factor tempering FGM/C also influenced the first three factors: Migration presented individuals in exile exposure to other cultural models, models that opposed FGM/C, thereby allowing sharper scrutiny of the practice.

DISCUSSION

Using results from this systematic review, the authors show that FGM/C is deeply rooted culturally and held in place by reciprocal expectations within practicing communities’ social systems. In the included studies, exiled members of practicing communities consistently argued that FGM/C was an essential cultural traditional and so must continue. Kleinman (1980) has described culture as an integrated pattern of human knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors as well as a set of shared values and practices that characterize a group. From this description it follows that, as Gali (1997) explains, FGM/C is embedded in many cultural systems through multiple ties to historical tradition, tribal affiliation, social status, marriageability, and religion. Most of these ties were perceptible in the datasets and will be discussed below. A related way of understanding FGM/C's continuance at the meso level through culture is by noting how it is culture congruent: According to Leininger (1997), the actions and decision for FGM/C are highly meaningful and preserve the valued lifeways of people in the community, whether in the home community or a Western host community. Or, as related to, for example, the Somalis, among whom the practice is near universal (Yoder & Khan, 2008), the practice has come to occupy an important place in the psyche of the society (Nkrumah, 1999). The results are also largely congruent with the WHO's “mental map” of why the practice continues. The WHO concluded that members of practicing communities held culturally ingrained beliefs about FGM/C, which formed a “mental map” and largely included psychosexual and social reasons, religion, society, and hygiene and aesthetics (WHO, 1999). It seems the reasons for FGM/C as viewed by individuals living in home communities are largely the same as those expressed by communities in Western exile. The results suggest that factors perpetuating FGM/C form a belief set, in which its value as a cultural tradition takes precedence. It is performed out of cultural conformity and, over time, the practice has developed social significance, signaling people's sense of identity and respectability as an ideal member of the community.

Today, including in the context of life in exile, FGM/C continues to be valued with strong support, socially and culturally. In fact, the results of exile communities’ reasons as expressed in the 1990s and 2000s show that a great deal of pressure is enforced within the communities. Accepting its place as a social organizing principle in practicing communities, the socially constructed normalizing mechanisms perceived by exile members are not wholly unexpected. Gilette-Frenoy (1992) writes that pressure to submit to the practice themselves or subject their daughters to it came from extended family members living in the West and those still residing in their countries of origin. On the one hand, findings showed that girls who undergo FGM/C, and their family, are met with social approval, notably respectability and honor (Khaja, 2004; Vissandjée et al., 2003). On the other hand, in response to failure to conform to FGM/C, social mechanisms included insulting an uncut girl's mother, teasing uncut girls, denying them social acceptance, and, most significantly, rejecting them as marriage partners (e.g., Ahlberg, Krantz, Lindmark, & Warsame, 2004; Berggren et al., 2006; Gali, 1997; Gilette-Frenoy, 1992; Khaja, 2004; Morison et al., 2004; Vissandjée et al., 2003). These findings show the role of FGM/C as a tool in social control. Refusing FGM/C would not only introduce the psychological problem of being different, but it also would shrink women's marriage prospects in their community. It is important to note that in most societies practicing FGM/C, being a wife and mother is of utmost value (Johnsdotter, 2002; Lightfoot-Klein, 1989; Nkrumah, 1999).

Relatedly, the results showed that the perpetuating factor of marriageability was significantly linked with the ideology of sexual morals. Many exile community members considered premarital virginity as a guarantee of moral standards, the fundamental assurance of marriageability. In the included studies and in other reports (e.g., Abor, 2006; Ebong, 1997), a belief that a woman's sexuality is wanton and therefore must be controlled through FGM/C was expressed. FGM/C is in this respect a means to control the sexuality of women analogous to the iron chastity belts allegedly used in medieval Europe. From a physiological perspective, implications of FGM/C on sexual desire and satisfaction have been substantiated (Berg & Denison, 2012), but the procedure does not ensure virginity, including among infibulated women—deinfibulation and reinfibulation can be and are performed (e.g., Levine, 1999; Thierfelder et al., 2005). Albeit not unquestioned (see, e.g., Johansen, 2007), the perception remains in the exile environment that through FGM/C, especially infibulations, girls bear witness of moral status and virginity (Johansen, 2007; Johnsdotter, 2002; Khaja, 2004). As with marriage, it must be recognized that the concept of virginity holds great importance in many practicing communities in that a family's and indeed the whole wider group's honor depends on girls’ chastity (Johansen, 2006; Khaja, 2004). Kassamali (1998) writes that in patrilineal societies, family honor is customarily closely associated with women's sexual behavior. As an example, in Sudanese society “the greatest measure of a family's honor is the sexual purity of its women. Any transgression on the part of the woman disgraces the whole family” writes Lightfoot-Klein (1989, p. 375).

The results showed that the argument of religion coexisted on two levels, reflecting the fact that a “true” Islamic position on FGM/C is impossible to claim, given those involved argue from their own interpretation of the written sources. There are four Islamic law schools, of which three regard FGM/C as recommended and one, the Shafi'i law school, regards FGM/C as compulsory. Each manifests differently, however, in various countries according to sociocultural practices (Roald, 2001). For example, FGM/C is virtually nonexistent in several countries that adhere to the Shafi'i law school (e.g., Palestine, Lebanon, Syria), but it is almost universal in others (e.g., Somalia; Roald, 2001). Lightfoot-Klein (1989) concluded that FGM/C is not practiced in an overwhelming majority of Muslim societies. Further, the genesis of FGM/C cannot be attributed to Islam as the practice was evident in pre-Islamic Arabia, the Middle East, and Africa (Barstow, 1999; Giladi, 1997; Grassivaro & Viviani, 1988). What is important is to draw attention to the fact that Islamic scholars interpret written sources differently. Additionally, while researchers believe that today's position of the Islamic scholars urges Muslims practicing FGM/C to adopt the most moderate form of FGM/C, many Muslims nevertheless understand clitoridectomy and infibulation to be religious duties (Giladi 1997; Kassamali, 1998). Because many parents who consider whether to perform FGM/C on their daughter are illiterate or religious texts are out of reach for them, they listen to Imams, who often endorse the practice (Gali, 1997). Grassivaro and Viviani (1988) write that FGM/C to lay people is seen as an authentic way to be religious, a sign of religious devotion. Further, linked to the discussion above, while some salafi Islamists consider FGM/C as a means to heighten female sexual desire, others regard it as a tool to reduce sexual desire (Roald, 2001). It seems that religious faith intersects with culture and sexuality in important ways.

As with religion, the findings showed that another consideration of FGM/C coexisted on two levels: FGM/C was seen as conferring health benefits while simultaneous viewed as having adverse health implications. Belief in purported benefits of FGM/C in general and hygiene in particular seemed to reflect that respondents found cut female genitals somehow cleaner. Conversely, participants were concerned about the intrapersonal level consequences following FGM/C, especially pain and women's reduced sexual responsiveness. According to leading health organizations, there are no known health benefits to FGM/C (WHO, 2008), and a recent meta-analysis confirmed that, statistically, a woman who has been subjected to FGM/C is more likely to experience pain during intercourse and reduction in sexual satisfaction and desire than a woman whose genital tissues have not been cut (Berg & Denison, 2012). Concerning men, one of their worries was interpersonal: women's suffering during intercourse. As one man in Johansen's study (2007) said, “How can I enjoy sex when it causes pain to my wife?” (p. 272). In fact, men's interest in FGM/C ostensibly center on FGM/C's role in preserving morality and honor, not providing sexual enjoyment (e.g., Johansen, 2007; Johnsdotter, 2002), contrary to what some female respondents suggested (e.g., Johnsdotter, 2002) and literature indicates (Khalifa, 1994).

As presented in the results section, exile communities considered the anti-FGM/C laws in Western countries and host society discourse's rejection of the practice as important macrolevel factors slowing its continuation. Since the early 1980s most Western countries have instituted legislation as their main FGM/C intervention tool (European Parliament, 2004; Leye & Sabbe, 2009), although neither their implementation nor effectiveness have been extensively studied (Johansen, Bathija, & Khanna, 2008; UNICEF, 2005a). While it is possible that the existence of a law in their host country may have influenced the community members’ responses to questions about whether they would continue the practice, the results suggest positive implications from FGM/C-related legislation. Migrating to a new social, political, and cultural context with specific laws seems to have led some to question the normalized practice of FGM/C.

In sum, the findings show that like other socially entrenched practices with benefits and sanctions anchored in a broad system of collective behavior, FGM/C derives from a complex belief set, in which reasons are at once ideological, material, and spiritual. As suggested above, important factors materialize at multiple levels: intrapersonal (e.g., health consequences), interpersonal (e.g., sexual enjoyment), meso (e.g., cultural tradition), and macro level (e.g., religion, legislation). Despite the grouped presentation of factors, the mutually reinforcing connections among the conditions influencing the practice should be recognized. For example, as shown in the conceptual model, some factors are perceived as both fueling and slowing the continuation of the practice. It demonstrates a migrant perspective of living in two worlds, where the multiple contexts and discourses surrounding FGM/C are negotiated and there is a cultural accommodation taking place. It also illustrates that FGM/C among exile communities is a tradition in transition with, in time, a likely transfer of relative weight to discontinuing the practice. In principle, then, the results are in agreement with Mackie (1996), who suggests that FGM/C as the “natural” way has become a belief trap. He explains that FGM/C is a self-enforcing belief, in which the cost of testing it has become so high that it traps people. Outside the realm of doxa, however, it seems that people are in a state of transition, which stimulates and enables them to reflect on values of home and host communities.

The results suggest that anti-FGM/C laws and actual court cases showing the effects of the law can be used as a deterrent within the communities concerned. The relevance of continuously and consistently informing citizens about the fact that FGM/C is prohibited by law and a human rights violation is indicated. While laws in themselves are not enough, they signal expectations by a government regarding the practice and they can work in a complementary fashion with prevention strategies, such as awareness, and educational intervention approaches by creating enabling environments for change. Findings are in agreement with UNICEF (2005b), suggesting that comprehensive social support mechanisms and awareness raising campaigns may be advantageous. Strategies of this kind may foster greater public discussion and reflection, such that previously nondiscussed costs of FGM/C may emerge as people share their experiences.

Future approaches should target stakeholders at the intrapersonal through to the macro levels. What is crucial is that information, messages, and activities are tailored to their audiences. Specifically, the results show that programs can also build upon existing beliefs about detrimental consequences from FGM/C and that the practice is not a religious obligation. The findings indicate advantages in establishing an alliance with religious leaders, who often function as norm authorities (WHO, 2008). Health promotion professionals can also aim to modify or remove continuance factors identified, such as correcting women's misperceptions regarding male sexual pleasure and informing community members of the greater likelihood of sexual problems with FGM/C. Regarding the other factors, findings showed that parents wanting their daughters to be successful in marriage and material opportunity chose the strategy of FGM/C. When migration removes pressure, and alternative options for social and economic survival other than FGM/C seem possible, parents and other community members will consider refraining from FGM/C. As one parent in Upvall and colleagues’ study (2009) stated, “If my daughter finishes school, learns how to drive a car, and gets a job, she doesn't need a man whether she is circumcised or not” (p. 364). This speaks to the importance of educational opportunities and economic independence for women.

Gaps and uncertainties in current research knowledge are highlighted. More research is needed especially among men. There would be advantages in researching the role of Islam in attitudinal change, the informational needs of the various FGM/C communities in Western locales, and avenues for effective dissemination of information. Groups who seek to encourage communities to discontinue FGM/C need to explore ways to address the belief set that sustains the practice. Although the results suggest factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C are fairly consistent across the many exile communities in the West, to optimally inform prevention efforts research should be done locally because the factors may vary somewhat across locations and time. The findings here form a clear starting point.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this systematic review is the comprehensive and systematic literature search as well as systematic process for identifying and analyzing relevant publications. A further strength is the inclusion of several study designs. This type of integrative approach, sometimes referred to as mixed studies review, is an emerging form of literature review in the health sciences (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Ploye, Gagnon, Griffiths, & Johnson-Lafleur, 2009). Such reviews, by consolidating often scattered literature on a defined topic, provide detailed and highly practical understanding of complex health issues (Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Ploye et al., 2009). The integrated results informed the review's conclusions and implications for research and practice that are optimally relevant for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers trying to understand FGM/C and behavior change, as well as groups contemplating prevention activities.

Advantages notwithstanding, the systematic review has some limitations. First, it may be subject to publication bias because it is not always possible to identify, and retrieve, all studies addressing the question of the systematic review. In contrast to effectiveness reviews, however, for synthesis of views studies this is probably a minor problem as it is unlikely that one large additional study would drastically change the results. Second, some caution is warranted in interpreting the results because about half of the studies had low methodological quality. Third, given the integrative nature of the synthesis it is possible that other review authors would produce a different overall model. The methods for conducting integrative syntheses are evolving, and there is no agreement about which approaches are best for particular types of data or questions (Dixon-Woods et al., 2005). Last, it is important to recognize that the identified factors are as perceived by exile communities living in Western countries in the 1990s and 2000s. Factors perceived as important likely change over time. Relatedly, it was not always clear whether the respondents in the included studies referred to situations in their home community or in their current exile setting. This is likely not problematic because many factors are, as described here, important in both contexts. FGM/C is embedded in cultural systems that transgress geographical boundaries. Understandably, this review does not mean to imply that there is unanimity among FGM/C practicing communities—the reasons for FGM/C are not everywhere the same—what the results show are recurring and dominant factors found in the recent literature involving exile communities in Western countries.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review summarized 21 empirical studies examining the factors perpetuating and hindering FGM/C as perceived by exile FGM/C communities living in Western countries. The integrative evidence synthesis identified that the practice of FGM/C derives from a complex belief set, in which cultural tradition takes precedence within a frame of sexual–moral and religious reasons that are sustained through community mechanisms. The results showed that within this intricate web of cultural, social, religious, and medical pretexts for FGM/C, conditions hindering its continuance existed, such as a legal framework and national discourse against FGM/C. Illustrated in a conceptual model, the reciprocal and dynamic relationships that these factors formed indicated that among practicing communities now living in a Western country, FGM/C is a tradition in transition.

REFERENCES

(References of studies included in the systematic review are identified with an asterisk)

- Abor P. A. Female genital mutilation: Psychological and reproductive health consequences. The case of Kayoro traditional area in Ghana. Gender and Behaviour. 2006;4(1):659–684. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlberg B. M., Krantz I., Lindmark G., Warsame M. Its only a tradition”: Making sense of eradication interventions and the persistence of female “circumcision” within a Swedish context. Critical Social Policy. 2004;24(1):50–78. [Google Scholar]

- Allag F., Abboud P., Mansour G., Zanardi M., Quéreux C. Female genital mutilation. Women's point of view. Gynecology Obstetric Fertilité. 2001;29:824–828. doi: 10.1016/s1297-9589(01)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barstow D. Female genital mutilation: the penultimate gender abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1999;23:501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg R. C., Denison E. Does female genital mutilation/cutting /FGM/C) affect women's sexual functioning? A systematic review of the sexual consequences of FGM/C. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2012;9(1):41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Berg R. C., Denison E., Fretheim A. Factors promoting and hindering the practice of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) Oslo, Norway: Report from Kunnskapssenteret (Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services); 2010. no. 23-2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren V., Bergström S., Edberg A. Being different and vulnerable: experiences of immigrant African women who have been circumcised and sought maternity care in Sweden. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006;17(1):50–57. doi: 10.1177/1043659605281981. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black Women's Health and Family Support Group. Attitudes and views of east African women and men on FGM. London, England: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers B., Hashi K. 432 Somali women's birth experiences in Canada after earlier female genital mutilation. Birth. 2000;27:227–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00227.x. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers B., Hashi K. What Somali women say about giving birth in Canada. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2002;20:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M., Agarwal S., Jones D., Young B., Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: A review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2005;10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M., Bonas S., Booth A., Jones D. R., Miller T., Sutton A. J., Young B. How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research. 2006;6(1):27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ebong R. D. Female circumcision and its health implications: A study of the Uruan locale government area of Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. Journal of the Royal Society of Health. 1997;117(2):95–99. doi: 10.1177/146642409711700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgaali M., Strevens H., Mårdh P. Female genital mutilation—An exported medical hazard. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. 2005;10(2):93–97. doi: 10.1080/13625180400020945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Combating violence against women. European Parliament resolution on the current situation in combating violence against women and any future action (2004/2220(INI)) 2004. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P6-TA-2006-0038+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN.

- Gali M. Female circumcision: A transcultural study of attitudes, identity and reproductive health of east African immigrants. Ann Arbor, MI: Wright Institute Graduate School of Psychology, University of Michigan; 1997. (Ph.D. dissertation.)∗. [Google Scholar]

- Giladi A. Normative Islam versus local traditions: Some observations on female circumcision with special reference to Egypt. Arabica. 1997;44:254–267. [Google Scholar]

- Gilette-Frenoy I. The practice of clitoridectomy in France. L'ethnographie. 1992;112:21–50. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Grassivaro P. G., Viviani F. Female circumcision in Somalia. The Mankind Quarterly. 1988;19(1–2):165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Guerin P. B., Allotey P., Elmi F. H., Baho S. Advocacy as a means to an end: Assisting refuge women to take control of their reproductive health needs. Women & Health. 2006;43(4):7–25. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n04_02. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden A., Garcia J., Oliver S., Rees R., Shepherd J., Brunton G., Oakley A. Applying systematic review methods to studies of people's views: An example from public health research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:794–800. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington S. Clash of civilizations, and the remaking of world order. New York, NY: Touchstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen R.E.B. Experiences and perceptions of pain, sexuality, and childbirth: A study of female genital cutting among Somalis in Norwegian exile, and their health providers. Norway: Institute of General Practice and Social Medicine, University of Oslo; 2006. (Ph.D. dissertation.) [Google Scholar]

- Johansen R.E.B. Experiencing sex in exile: Can genitals change their gender? On conception and experiences related to female genital cutting (FGC) among Somalis in Norway. In: Hernlund Yl., Shell-Duncan B., editors. Transcultural bodies: Female genital cutting in global context. London, England: Rutgers University Press; 2007. pp. 248–277. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen R.E.B., Bathija H., Khanna J. Work of the World Health Organization on female genital mutilation: Ongoing research and policy discussions. Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration. 2008;3:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsdotter S. Created by God. How Somalis in Swedish exile reassess the practice of female circumcision. Sweden: Department of Social Anthropology, Lund University; 2002. (Ph.D. dissertation.) [Google Scholar]

- Johnsdotter S. Somali women in Western exile: Reassessing female circumcision in the light of Islamic teachings. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 2003;23:361–373. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsdotter S. Persistence of tradition or reassessment of cultural practices in exile? Discourses on female circumcision among and about Swedish Somalis. In: Hernlund Yl., Shell-Duncan B., editors. Transcultural Bodies: Female genital cutting in global context. London, England: Rutgers University Press; 2007. pp. 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsdotter S. “Never my daughters”: A qualitative study regarding attitude change toward female genital cutting among Ethiopian and Eritrean families in Sweden. Health Care for Women International. 2009;30:114–133. doi: 10.1080/07399330802523741. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan-Marcusan A., Fernández del Rio N., Moreno-Navarro J., Castany-Fàbregas M. J. C., Nogueras M. R., Muñoz-Ortiz L., Torán-Monserrat P. Female genital mutilation: Perception of healthcare professionals and the perspective of the migrant families. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(193) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan-Marcusan A., Torán-Monserrat P., Moreno-Navarro J., Fàbregas M.J.C., Muñoz-Ortiz L. Perception of primary health professionals about Female genital mutilation: From healthcare to intercultural competence. BMJ Health Services Research. 2009;9(11) doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassamali N. J. When modernity confronts traditional practices: Female genital cutting in northeast Africa. In: Bodin H. L., Tohidi N., editors. Women in Muslim societies, diversity within unity. London, England: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 1998. pp. 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Khaja K. Female circumcision: Life histories of Somali women. Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: University of Utah; 2004. (Ph.D. dissertation.)∗. [Google Scholar]

- Khaja K., Barkdull C., Augustine M., Cunningham D. Female genital cutting. African women speak out. International Social Work. 2009;52:727–741. [Google Scholar]

- Khaja K., Lay K., Boys S. Female circumcision: Toward an inclusive practice of care. Health Care for Women International. 2010;31:686–699. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.490313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa N. K. Reasons behind practicing re-circumcision among educated Sudanese women. The Ahfad Journal—Women and Change. 1994;11(2):16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture. An exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. London, England: University of California Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leininger M. M. Overview of the theory of culture care with the ethnonursing research method. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 1997;8(2):32–52. doi: 10.1177/104365969700800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A. Female genital operations: Canadian realities, concerns, and policy recommendations. In: Trope H. M., Weinfeld M., editors. Ethnicity, politics, and public policy: Case studies in Canadian diversity. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press; 1999. pp. 26–53. [Google Scholar]

- Leye E., DeBlonde J., Garcia-Añon J., Johnsdotter S., Kwateng-Kluvitse A., Weil-Curiel L., Temmerman M. An analysis of the implementation of laws with regard to female genital mutilation in Europe. Crime, Law & Social Change. 2007;47:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Leye E., Sabbe A. A review of legislation. Ghent, Belgium: International Centre for Reproductive Health, Ghent University; 2009. Responding to female genital mutilation in Europe. Striking the right balance between prosecution and prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot-Klein H. The sexual experience and marital adjustment of genitally circumcised and infibulated females in the Sudan. The Journal of Sex Research. 1989;26:375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Litorp H., Franck M., Almroth L. Female genital mutilation among antenatal care and contraceptive advice attendees in Sweden. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2008;87:716–722. doi: 10.1080/00016340802146938. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg P. C., Gerezgiher A. Experiences from pregnancy and childbirth related to female genital mutilation among Eritrean immigrant women in Sweden. Midwifery. 2008;24:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.10.003. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie G. Ending footbinding and infibulations: A convention account. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:999–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Morison L. A., Dirir A., Elmi S., Warsame J., Dirir S. How experiences and attitudes relating to female circumcision vary according to age on arrival in Britain: A study among young Somalis in London. Ethnicity & Health. 2004;9(1):75–100. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000202763. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris R. The culture of female circumcision. Advances in Nursing Science. 1996;19(2):43–53. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199612000-00006. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi-Powell F. The SWITCH project: A FGM related study. London, England: FORWARD; 1999. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi-Powell F. Female genital mutilation: A case study in Birmingham. London, England: FORWARD; 2001. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Nkrumah J. Unuttered screams: the psychological effects of female genital mutilation. In: Ferguson B., Pittaway E., editors. Nobody wants to talk about it: refugee women's mental health. Paramatta, NSW: Transcultural Mental Health Centre; 1999. pp. 54–73. [Google Scholar]

- Norman K., Hemmings J., Hussein E., Otoo-Oyortey N. FGM is always with us. Experiences, perceptions and beliefs of women affected by female genital mutilation in London. Results from a PEER study. London, England: FORWARD; 2009. ∗. [Google Scholar]

- Ploye P., Gagnon M., Griffiths F., Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for apprising qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:529–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poldermans S. Combating female genital mutilation in Europe. A comparative analysis of legislative and preventative tools in the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, and Austria. Austria: University of Vienna; 2006. (European Masters’ degree in human rights and democratisation.) [Google Scholar]

- Roald A. S. Women in Islam: The Western experience. London, England: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M., Barrows J. Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research. 2003;137:905–923. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253488. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J., Harden A., Rees R., Brunton G., Garcia J., Oliver S., Oakley A. Young people and healthy eating: A systematic review of research on barriers and facilitators. Health Education Research, Theory & Practice. 2006;21:239–257. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sy M. B. Excision and social change in Mauritania and the migratory populations. 1993. Unpublished manuscript.

- Thierfelder C., Tanner M., Bodiang C. M. Female genital mutilation in the context of migration: Experiences of African women with the Swiss health care system. European Journal of Public Health. 2005;15(1):86–90. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2008;8(45) doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Female genital mutilation/female genital cutting: a statistical exploration. New York, NY: Author; 2005a. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/FGM-C_final_10_October.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Changing a harmful social convention: Female genital mutilation/cutting. New York, NY: Author; 2005b. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.at/fileadmin/medien/pdf/FGM-C_English-nov05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Upvall M. J., Mohammed K., Dodge P. D. Perspectives of Somali Bantu refugee women living with circumcision in the United States: A focus group approach. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2009;46:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.04.009. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissandjée B., Kantiébo M., Levine A., N'dejuru R. The cultural context of gender identity: Female genital excision and infibulations. Health Care for Women International. 2003;24:115–124. doi: 10.1080/07399330390170097. ∗. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Female genital mutilation. A joint WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA statement. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Female genital mutilation. Programmes to date: What works and what doesn't. A review. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1999. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_CHS_WMH_99.5.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) A systematic review of the health complications of female genital mutilation including sequelae in childbirth. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2000. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2000/WHO_FCH_WMH_00.2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Eliminating female genital mutilation: An interagency statement. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2008. Retrieved from http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2008/eliminating_fgm.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Study Group on Female Genital Mutilation and Obstetric Outcome. Female genital mutilation and obstetric outcome: WHO collaborative prospective study in six African countries. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1835–1841. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder S., Kahn S. Numbers of women circumcised in Africa: The production of a total. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development; 2008. DHS working papers, 39. Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/WP39/WP39.pdf. [Google Scholar]