Abstract

Background

To report on the incidence and predictors of use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) among patients with thyroid cancer.

Methods

Data were collected using a web-based online anonymous survey under Institutional Review Board approval from Boston University. This report is based on 1327 responses from subjects with thyroid cancer. Patient factors were compared by univariate and multivariate analyses.

Results

After excluding multivitamin and prayer use, 74% (n=941) used CAM. Respondents were primarily over age 40, white, and female and held a college degree. The top five modalities were massage therapy, chiropraxy, special diets, herbal tea, and yoga. Few patients reported perceiving a particular modality had a negative effect on treatment. CAM was more often used for treatment of symptoms (73%) than as part of thyroid cancer treatment (27%). Multivariable logistic regression demonstrated that patients reporting a poor health status, higher education, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary symptoms, or persistent, recurrent, or metastatic disease were more likely to use CAM for treatment of thyroid cancer symptoms. Nearly one third of respondents reported their CAM use was not known, prescribed, or asked about by their physicians.

Conclusions

In comparison to national surveys of the general U.S. population, patients with thyroid cancer use CAM therapies twice as often and report their use far less often. Physicians who treat patients with thyroid cancer should be aware of these data to further assist in their assessment and care.

Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is defined by the National Institutes of Health as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine. According to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey, one third of U.S. adults have used some form of CAM (1,2) with annual costs estimated to exceed $4 billion (3,4). CAM practices are usually grouped into four broad categories: natural products, mind and body medicine practices, manipulative practices, and body-based practices. The majority of patients using CAM approaches do so to complement their conventional care rather than as an alternative (5–7). By definition, CAM practices are not part of conventional medicine. In part, this may be because there is insufficient proof that they are safe and effective. CAM is used for a wide range of common problems including pain, the common cold, stiffness, anxiety, and depression (1,2). Patients often use CAM approaches to treat or provide symptom relief for cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and lung diseases (1,8). In particular, CAM use is more prevalent among women, adults with higher educational attainment, and in individuals with existing health conditions who make frequent medical visits to conventional health care professionals (1). Many of these descriptors apply to patients with thyroid cancer (9). Patients' use of therapies other than those prescribed by their allopathic physicians must be acknowledged and assessed for their impact on conventional medical therapies.

While there have been surveys conducted to analyze CAM use specifically in patients with cancer (10–23), the number of patients with thyroid cancer in these surveys were small, definitions of what constitutes CAM therapy varied, and questions were not specific to thyroid cancer. The incidence and prevalence of CAM use among patients with thyroid cancer is therefore not known.

Despite the high prevalence of patient use, fewer than half of patients who use CAM typically discuss it with their clinician, and health care professionals do not consistently inquire about or record patients' use of CAM (7,24–26). This is concerning because the potential for interactions between CAM modalities and patients' thyroid cancer treatment is unknown; for example, the interaction with radioactive iodine ablation or thyroid hormone suppressive therapy. The primary goal for this study was to assess the incidence and prevalence of CAM use among patients with thyroid cancer. We examined the relationships between CAM use, demographics, and cancer treatment among patients with thyroid cancer and assessed the extent to which patients communicated their CAM use to their providers.

Patients and Methods

Survey development and design

The survey was developed by the investigators, with guidance from thyroid cancer, CAM research, and health-information technology experts and was designed as an observational study. We systematically reviewed previous surveys focusing on CAM use in cancer patients. The survey is based on the 2007 National Health Interview Survey Alternative Medicine Supplemental Questionnaire (27) and includes all 27 types of CAM therapies commonly used in the United States, 10 types of provider-based CAM therapies, and 17 self-administered CAM therapies. The survey was piloted online with a small group of thyroid cancer patients (n=5). There were four main categories: overall health status, demographic information, questions on CAM use, and general CAM use questions. Although the survey format included both closed and open-ended questions, only the closed-ended question results are reported here.

Sample and subjects

This study was conducted under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus from June 2009 to January 2012. No identifiable data were requested. An online program was used to administer the survey (SurveyMonkey, Portland, Oregon), which allowed for electronic self-administration and data collection. Participants accessed the survey from the website of a national thyroid cancer survivorship group. We opened the survey in June 2009 and closed it in January 2012. The initial request for survey participation was sent by an invitation e-mail (via dedicated listserv) from the director of the large thyroid cancer survivor's organization (ThyCa), and a follow-up reminder was sent through the same listserv 2 months later. The page was left open over 30 months to avoid early-respondent bias. We therefore included patients who were members of the survivorship group, had access to the website, and self-identified as having thyroid cancer. We excluded patients who did not have online access, chose not to voluntarily participate, and those who were not literate in English. Of the approximately 15,000 potentially eligible respondents who were members of the survivorship group, 1327 completed the survey. Study participants did not receive compensation for their participation, to minimize participation bias. The data were analyzed for discrepancies in data collection; four duplicate entries using Internet protocol addresses were captured by the online survey program and discarded. Participants were informed that the survey would take approximately 30 minutes to complete, no identifiable information would be requested, it was anonymous, completion was voluntary, and there were no financial incentives. Consent was implied if they completed the survey. The electronic survey did allow for blank responses to permit participants the right of refusal to answer sensitive questions.

Item nonresponse

The overall item completion rate was 82%. Among the 1327 survey respondents, 170 had incomplete or missing data for some of the CAM therapy items and therefore were imputed as detailed in the analysis section; statistical analysis did not demonstrate a significant difference if performed with and without missing data. Surveys that were started but not completed were used in the final analysis as long as more than 25% of the survey was completed.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated using means and standard deviations for normally distributed data and medians for nonnormally distributed data. Descriptive data were calculated for respondent characteristics and responses to survey questions. Two-way comparisons were tested by chi-square for nominal and categorical data.

We grouped patients into three stages of care: initial management, follow-up, and “other.” The other category included those with no clean scan but no current treatment, patients undergoing chemotherapy or enrolled in clinical trials, patients who had undergone multiple radioactive iodine treatments, patients with recurrences undergoing evaluation and treatment, patients with elevated thyroglobulin antibodies and/or elevated thyroglobulin levels, and patients undergoing external beam radiation therapy.

We developed two models for logistic regression. The first was to predict use of CAM excluding prayer/multivitamins. We chose to do this because there is extensive debate as to whether prayer or multivitamins are truly CAM. We do present the data on prayer/multivitamin use in our results, but do not include it in the logistic regression for this reason. We chose to examine these predictors in order to compare our survey with other surveys examining CAM use. The second model was to predict CAM use for thyroid cancer symptoms. We chose to build this model because this would be of greatest interest to physicians who treat patients with thyroid cancer to focus attention in the future on potential interactions and reasons for nonresponse to therapy. Sixty-one individuals were excluded from the logistic regression model because they were missing five or more significant demographic variables (age, ethnicity, education, household income, smoking status, alcohol status), yielding a sample of 1266 patients for the final logistic regression modeling. We used a standard statistical method, multiple imputations (28); variables for which we imputed missing demographic and lifestyle data included age, ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, income, self-reported health, chronic health conditions, heart, lung, gastrointestinal or neurological symptoms, number of times visiting a primary care physician (provider [PCP]), lifetime cigarette status, and lifetime alcohol status and were extrapolated from the entire group. Multiple imputations allow us to systematically predict values for missing variables based on demographic trends within the data set. The models were adjusted for age, ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, self-reported health, smoking status, alcohol status, and stage of cancer treatment. We chose these variables based on three criteria: significant on univariate analysis, important in predicting CAM use in the general population, and prognostic in patients with thyroid cancer.

Results

We collected surveys from 1327 patients with thyroid cancer. Table 1 gives a descriptive overview of demographic and lifestyle characteristics for the individuals included in the logistic regression (n=1266). After excluding multivitamin and prayer use, 74% (n=941) of the population used CAM. Of all 1266 patients, 73% (n=919) were over the age of 40 years with the mean age of 47 years, 89% (n=1123) identified as white, 89% (n=1123) were female, and 76% (n=961) had obtained a college or graduate degree. Seventy-three percent (n=927) were married or partnered and 70% (n=896) had an income above $50,001. Sixty-one percent (n=771) described their health as good. Sixty-one percent (n=771) did not have any chronic health conditions. Symptoms reported by respondents were heart or hematological (46%, n=587), lung (41%, n=523), gastrointestinal or urinary (55%, n=700), and neurological (69%, n=868). Forty-five percent (n=568) of subjects had seen a PCP more than three times in the last 12 months. Sixty-five percent (n=822) of the population never smoked, and 68% (n=846) were social drinkers or had quit drinking. Forty-eight percent (n=607) were in follow-up for thyroid cancer treatment.

Table 1.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Participants by Demographic Variable

| |

|

CAM excluding prayer/MV [N (%)] |

CAM used for thyroid cancer symptoms [ N (%)] |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All respondents[N (%)] | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Total | 1266 | 941 | 325 | 380 | 886 |

| Age, years | p=0.002* | p=0.002* | |||

| 18–39 | 333 (26) | 259 (28) | 74 (23) | 125 (33) | 208 (24) |

| 40–49 | 363 (29) | 267 (28) | 96 (29) | 114 (30) | 249 (28) |

| 50–59 | 387 (31) | 294 (31) | 93 (28) | 99 (26) | 288 (32) |

| 60+ | 169 (13) | 116 (12) | 53 (16) | 39 (10) | 130 (15) |

| Missing | 14 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 (3) | 3 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Ethnicity | p=0.164 | p=0.0097* | |||

| White | 1123 (89) | 830 (88) | 293 (90) | 325 (86) | 798 (90) |

| Othera | 136 (11) | 108 (12) | 28 (9) | 54 (14) | 82 (9) |

| Missing | 7 | 3 | 4 (1) | 1 | 6 (1) |

| Sex | p=0.012* | p=0.293 | |||

| Female | 1122 (89) | 844 (90) | 278 (85) | 340 (90) | 782 (88) |

| Male | 135 (11) | 88 (9) | 47 (15) | 35 (9) | 100 (11) |

| Missing | 9 | 9 (1) | 0 | 5 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Education | p=0.0098* | p=0.131 | |||

| Less than high school, or technical school | 69 (6) | 48 (5) | 21 (7) | 18 (5) | 51 (6) |

| High school or GED | 231 (18) | 155 (16) | 76 (23) | 58 (15) | 173 (20) |

| College or graduate school | 961 (76) | 734 (78) | 227 (70) | 302 (80) | 659 (74) |

| Missing | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Marital status | p=0.319 | p=0.357 | |||

| Single, separated or divorced | 334 (26) | 255 (27) | 79 (24) | 107 (28) | 227 (26) |

| Married or partnered | 927 (73) | 682 (72) | 245 (75) | 272 (72) | 655 (74) |

| Missing | 5 | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 | 4 |

| Annual income | p=0.304 | p=0.002* | |||

| <$50,000 | 310 (25) | 241 (26) | 69 (21) | 115 (30) | 195 (22) |

| $50,001–$100,000 | 498 (39) | 366 (39) | 132 (41) | 154 (41) | 344 (39) |

| >$100,000 | 398 (31) | 291 (31) | 107 (33) | 98 (26) | 300 (34) |

| Missing | 60 (5) | 43 (5) | 17 (5) | 13 (3) | 47 (5) |

| Self-reported health | p=0.012* | p=0.009* | |||

| Excellent | 222 (18) | 158 (18) | 64 (20) | 56 (15) | 161 (19) |

| Good | 771 (61) | 562 (60) | 209 (64) | 224 (59) | 547 (62) |

| Fair/poor | 268 (21) | 218 (23) | 50 (15) | 100 (26) | 168 (19) |

| Missing | 5 | 3 | 2 (1) | 0 | 5 |

| Cardiovascular diseaseb | p=0.489 | p=0.005* | |||

| Yes | 484 (38) | 355 (38) | 129 (40) | 123 (32) | 361 (41) |

| No | 771 (61) | 579 (62) | 192 (59) | 253 (67) | 518 (58) |

| Missing | 11 (1) | 7 | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 7 (1) |

| Have you ever had symptoms related to...? | |||||

| Heart or hematologic | p=0.013* | p=0.538 | |||

| Yes | 587 (46) | 456 (49) | 131 (40) | 170 (45) | 417 (47) |

| No | 661 (52) | 473 (50) | 188 (58) | 202 (53) | 459 (52) |

| Missing | 18 (2) | 12 (1) | 6 (2) | 8 (2) | 10 (1) |

| Lung | p=0.013* | p=0.011* | |||

| Yes | 523 (41) | 409 (44) | 114 (35) | 179 (47) | 344 (39) |

| No | 724 (57) | 521 (55) | 203 (63) | 199 (52) | 525 (59) |

| Missing | 19 (2) | 11 (1) | 8 (2) | 2 (1) | 17 (2) |

| Gastrointestinal or urinary | p=0.095 | p=0.940 | |||

| Yes | 700 (55) | 534 (57) | 166 (51) | 209 (55) | 491 (56) |

| No | 549 (43) | 396 (42) | 153 (47) | 165 (43) | 384 (43) |

| Missing | 17 (1) | 11 (1) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 11 (1) |

| Neurologic | P<0.0001* | p=0.079 | |||

| Yes | 868 (68) | 678 (72) | 190 (58) | 273 (72) | 595 (67) |

| No | 388 (31) | 256 (27) | 132 (41) | 103 (27) | 285 (32) |

| Missing | 10 (1) | 7 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) | 6 (1) |

| How many times did you visit your PCP in the last 12 months? | p=0.089 | p=0.067 | |||

| None | 100 (8) | 77 (8) | 23 (7) | 36 (9) | 64 (7) |

| 1–2 | 589 (47) | 418 (44) | 171 (53) | 158 (42) | 431 (49) |

| 3–4 | 340 (27) | 259 (28) | 81 (25) | 107 (28) | 233 (26) |

| 5+ | 228 (18) | 179 (19) | 49 (15) | 79 (21) | 149 (17) |

| Missing | 9 (1) | 8 (1) | 1 | 0 | 9 (1) |

| Lifetime cigarette smoking status | p=0.528 | p=0.150 | |||

| Never | 822 (65) | 606 (64) | 216 (66) | 240 (63) | 582 (66) |

| Occasionally or regularly smoke | 104 (8) | 82 (9) | 22 (7) | 40 (10) | 64 (7) |

| Quit smoking or otherc | 326 (26) | 243 (26) | 83 (26) | 97 (26) | 229 (26) |

| Missing | 14 (1) | 10 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Lifetime alcohol drinking status | p=0.020* | p=0.072 | |||

| Never drink | 315 (25) | 224 (24) | 91 (28) | 78 (21) | 237 (27) |

| Social drinker or quit drinking | 846 (68) | 647 (69) | 199 (61) | 268 (70) | 578 (65) |

| Regular drinking | 95 (7) | 62 (6) | 33 (10) | 28 (7) | 67 (8) |

| Missing | 10 | 8 (1) | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | 4 |

| Where are you in your care? | p=0.140 | p=0.002* | |||

| Initial management | 285 (22) | 199 (21) | 86 (26) | 71 (19) | 214 (24) |

| Follow-up | 607 (48) | 460 (49) | 147 (45) | 171 (45) | 436 (49) |

| Otherd | 374 (30) | 282 (30) | 92 (28) | 138 (36) | 236 (27) |

Other ethnicity includes Hispanic, Latino, Caribbean, Native American, Asian, Black, African, Filipino, and aboriginal.

Cardiovascular disease assessed with the question: Do you have diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol?

Other smoking includes rare social smoking, exposure to secondhand smoke, cigar smoking, and remote history of smoking.

Where in care other category includes no clean scan but no current treatment, patients undergoing chemotherapy, patients who have undergone multiple radioactive iodine treatments, patients enrolled in treatment clinical trials, patients with recurrences undergoing evaluation and management, patients with elevated thyroglobulin antibody level, and/or elevated serum thyroglobulin level, and patients undergoing external beam radiation therapy.

Significant at the 0.05 level.

CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; MV, multiple vitamins; GED, general equivalency diploma; PCP, primary care physician (provider).

Table 2 reports the frequencies of the various CAM modalities, whether the modality was used for thyroid cancer, and the self-perceived effect the modality had on the individual's thyroid cancer treatment. The top five CAM modalities used were massage therapy (n=450, 48% of CAM users), chiropractic (n=372, 40% of CAM users), special diets (n=355, 38% of CAM users), herbal tea (n=332, 35% of CAM users), and yoga (299, 32% of CAM users). For CAM used specifically for thyroid cancer symptoms, the top five CAM modalities were special diets (n=222, 24% of CAM users), meditation (n=63, 6.7% of CAM users), herbal supplements (n=49, 5% of CAM users), herbal tea (n=41, 4.4%), and massage therapy (n=35, 3.7% of CAM users). All therapies listed on the questionnaire had at least one respondent who reported use, including provider-based therapies such as Voodoo, espiritism, Santeria, and bloodletting.

Table 2.

Frequency of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Modalities Among All Respondents (N=1327)

| Therapy | No. of respondents using modality | Used for thyroid cancer overall N=361 [N (%)] | Helped my treatment [N (%)] | Had no effect on my treatment [N (%)] | Had a bad effect on my treatment [N (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mind and body medicine | |||||

| Yoga | 299 | 24 (8)a | 142 (47) | 63 (21) | 1 (0.3) |

| Meditation | 241 | 63 (26) | 149 (62) | 28 (12) | 0 |

| Acupuncture | 185 | 27 (15) | 77 (42) | 37 (20) | 5 (3) |

| Acupressure | 61 | 3 (5) | 26 (43) | 13 (21) | 0 |

| Hypnosis | 40 | 6 (15) | 9 (23) | 10 (25) | 0 |

| Cupping | 26 | 3 (12) | 6 (23) | 6 (23) | 1 (4) |

| Manipulative body based | |||||

| Massage therapy | 450 | 35 (8) | 228 (51) | 107 (24) | 3 (1) |

| Chiropractor | 372 | 11 (3) | 139 (37) | 111 (30) | 2 (1) |

| Natural products | |||||

| MV/megamultivitamins | 642 | 125 (19) | 242 (38) | 168 (26) | 3 (0.5) |

| Special diets | 355 | 222 (63) | 208 (59) | 47 (13) | 4 (1) |

| Herbal tea | 332 | 41 (12) | 96 (29) | 109 (33) | 1 (0.3) |

| Herbal supplements | 245 | 49 (20) | 97 (40) | 55 (22) | 1 (0.4) |

| Home remedies, folk remedies, poultices, etc. | 78 | 16 (21) | 36 (46) | 10 (13) | 1 (1) |

| Other CAM practices | |||||

| Homeopathy | 199 | 31 (16) | 79 (40) | 55 (28) | 6 (3) |

| Saunas | 81 | 8 (10) | 26 (32) | 19 (23) | 0 |

| Things you wear (protection, bands, etc.) | 66 | 21 (32) | 29 (44) | 19 (29) | 1 (2) |

| Naturopathy | 48 | 23 (48) | 28 (58) | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Cleansing rituals | 34 | 8 (24) | 13 (38) | 8 (24) | 0 |

| Colonics | 28 | 8 (29) | 12 (43) | 5 (18) | 1 (4) |

| Ayurveda | 18 | 4 (22) | 6 (33) | 5 (28) | 1 (6) |

| Chelation therapy | 11 | 2 (18) | 2 (18) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| Vodun | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Espiritism | 4 | 3 (75) | 2 (50) | 0 | 0 |

| Bloodletting | 4 | 0 | 1 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Santeria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spiritual | |||||

| Prayer for health reasons | 581 | 365 (63) | 360 (62) | 35 (6) | 0 |

| Spiritual or religious healing | 186 | 112 (60) | 118 (63) | 8 (4) | 1 (1) |

Percent represents the percentage of respondents using modality. For example, 8% of those reporting yoga used the modality for thyroid cancer symptoms.

The CAM use variable excluded multivitamins and prayer for the purposes of the logistic regression. Forty-eight percent (n=642) of the 1327 respondents had used multivitamins. Forty-four percent (n=581) of the total population used prayer for health reasons. Sixty-three percent of those individuals used prayer specifically for their thyroid cancer symptoms (n=365). Fourteen percent (n=186) had used spiritual or religious healing. Sixty percent of those individuals used spiritual or religious healing for their thyroid cancer symptoms (n=116).

There was an overwhelming trend towards patients reporting their perception that CAM either helped their treatment or had no significant effect on their treatment. Sixty-two percent of individuals using meditation (n=149) reported it helped their treatment. Of those using massage therapy (n=450), 51% of individuals (n=228) believed it had helped their treatment. Very few patients reported perceiving a particular modality had a harmful effect.

Odds ratios, confidence intervals, and p values for an adjusted multivariable logistic regression are reported in Table 3. In our first model, we assessed factors associated with overall CAM use. Patients with a college or graduate degree were more likely to use CAM (OR 1.372 [CI 1.084–1.738]) compared with those who went to technical school or had less than a high school education. Patients who reported neurological symptoms were slightly more likely to use CAM overall (OR 1.266 [CI 1.087–1.474]). We found that those who were social drinkers or who had quit drinking were 1.314 times more likely to use CAM [CI 1.074–1.609] compared with those who were regular consumers of alcohol.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analyses Examining Characteristics Associated with Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine and with Its Use Specifically for Thyroid Cancer Symptoms

| |

CAM excluding prayer/MV |

CAM used for thyroid cancer symptoms |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school, or technical school | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| High school or GED | 0.775 | [0.593, 1.013] | 0.062 | 0.848 | [0.639, 1.126] | 0.255 |

| College or graduate school | 1.372 | [1.084, 1.738] | 0.009 | 1.305 | [1.023, 1.664] | 0.032 |

| Income | ||||||

| <$50,000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| $50,001–$100,000 | 0.964 | [0.802, 1.158] | 0.698 | 1.083 | [0.911, 1.287] | 0.366 |

| >$100,000 | 0.960 | [0.777, 1.185] | 0.700 | 0.704 | [0.572, 0.866] | 0.001 |

| Self-reported health | ||||||

| Excellent | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Good | 0.854 | [0.711, 1.026] | 0.092 | 0.958 | [0.805, 1.139] | 0.625 |

| Poor | 1.284 | [0.991,1.664] | 0.058 | 1.291 | [1.027, 1.622] | 0.029 |

| Cardiovascular diseasea | ||||||

| Yes | 0.958 | [0.828, 1.110] | 0.569 | 0.845 | [0.732, 0.975] | 0.021 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Had symptoms related to the following conditions | ||||||

| Heart or hematologic | ||||||

| Yes | 1.060 | [0.920, 1.220] | 0.422 | 0.885 | [0.772, 1.013] | 0.078 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lung | ||||||

| Yes | 1.094 | [0.946, 1.266] | 0.227 | 1.196 | [1.044, 1.370] | 0.010 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastrointestinal or urinary | ||||||

| Yes | 0.960 | [0.827, 1.113] | 0.584 | 0.961 | [0.835, 1.107] | 0.583 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Neurologic | ||||||

| Yes | 1.266 | [1.087, 1.474] | 0.002 | 1.063 | [0.9111, 1.240] | 0.438 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lifetime alcohol drinking status | ||||||

| Never drink | 1.057 | [0.827, 1.351] | 0.656 | 0.791 | [0.615, 1.017] | 0.067 |

| Social drinker or quit drinking | 1.314 | [1.074, 1.609] | 0.008 | 1.164 | [0.948, 1.429] | 0.146 |

| Regular drinking | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Where are you in your care? | ||||||

| Initial management | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Follow-up | 1.122 | [0.940, 1.339] | 0.204 | 0.933 | [0.786, 1.108] | 0.431 |

| Other | 1.066 | [0.876, 1.295] | 0.526 | 1.340 | [1.116, 1.609] | 0.002 |

Results adjusted for age, ethnicity, sex, marital status, PCP utilization, and smoking status.

Cardiovascular disease assessed with the question: Do you have diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol?

In our second model, we examined CAM used specifically for thyroid cancer symptoms. We found that respondents with a college or graduate degree were more likely to use CAM (OR 1.305 [CI 1.023–1.664]) compared with those who went to technical school or had less than a high school education. Respondents with an income greater than $100,000/year were slightly less likely to report using CAM for thyroid cancer symptoms (OR 0.704 [CI 0.572–0.866]) compared with those reporting an income less than $50,000/year. Patients self-reporting a poor health status were more likely to use CAM for thyroid symptoms (OR 1.291 [CI 1.027–1.622]) compared with those reporting an excellent health status. Individuals with cardiovascular disease were slightly less likely to use CAM for thyroid symptoms (OR 0.845 [CI 0.732–0.975]) compared with those without cardiovascular disease. Those with lung symptoms were 1.196 times more likely to use CAM for thyroid symptoms [CI 1.044–1.370] than those not reporting lung symptoms. Lastly, patients who were in the other stage of treatment were more likely to use CAM for thyroid symptoms (OR 1.340 [CI 1.116–1.609]) compared with those in initial management.

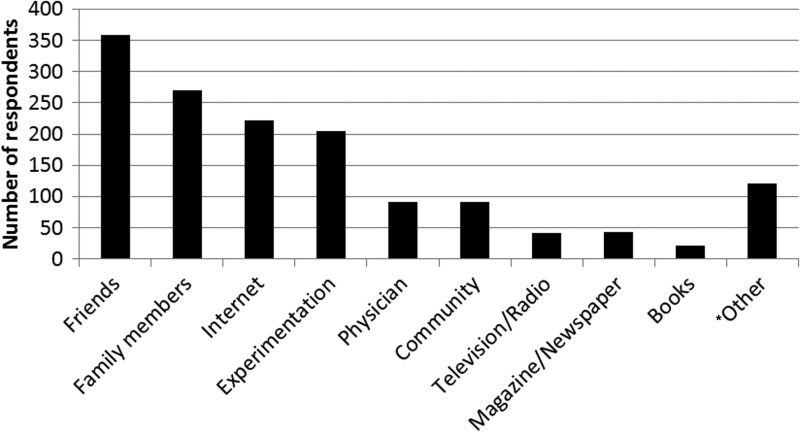

As seen in Figure 1, the most common methods for learning about CAM were through friends and family members, sources on the internet, and by experimentation. Most respondents reported learning through multiple methods.

FIG. 1.

Numbers of respondents by source of information for complementary and alternative medicine. Numbers add up to more than total respondents (1327) because participants could choose more than one source in response to this question. *Other included (in order of descending frequency): alternative physician, cancer center or hospital, church, or religious group. Six respondents who had thyroid cancer reported that they were also trained alternative practitioners including a massage therapist, chiropractor, reiki, and others.

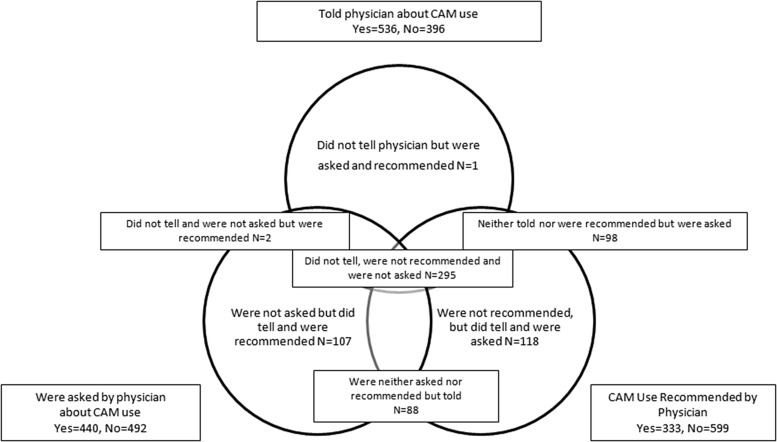

As seen in Figure 2, 99 (10%) of CAM users reported being asked about but did not tell their provider about CAM use, while 295 (31.3%) of CAM users reported they were neither asked nor did they tell their provider about CAM use.

FIG. 2.

Venn diagram outlining the proportion of respondents who used CAM therapies who reported CAM use to their providers, were asked about CAM use, and were either recommended or prescribed CAM use by their providers.

Discussion

This is the largest study to date to examine CAM use in patients with thyroid cancer and to assess factors associated with CAM use.

Overall, 74% of respondents with thyroid cancer used some form of CAM in the past 12 months. More women than men responded to this survey; this difference can be accounted for by the female preponderance among patients with thyroid cancer. The high rate of CAM use in our sample exceeds rates reported in studies of the general U.S. population and patients with cancer (1). This may be because we specifically asked about numerous vitamins, minerals, and herbs, because CAM users may be motivated to respond to our survey, or that patients with thyroid cancer truly have a higher incidence of CAM use, which would require validation in future studies.

Our survey has several important characteristics. This includes questions about use of an extensive list of CAM approaches, questions about reasons for use and perceived efficacy, and extensive information regarding disease-defining treatment. Data from this survey, therefore, can be linked to a wide variety of respondent characteristics, which leads to a rich analytic potential. Most prior surveys failed to identify the diseases and/or conditions associated with CAM use, relied on creating estimates from small samples, or failed to include questions about reasons for CAM use. Consistent with prior studies, this study finds that the majority of individuals reporting use of CAM were doing so in conjunction with conventional medicine as measured by the fact that most respondents reported at a minimum having a PCP and a visit at least once in the prior year.

The high prevalence of CAM use for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer is interesting given that there are standardized, effective ways to manage this disease. Many respondents used CAM specifically to treat their thyroid cancer although a high proportion of these reported use of CAM for related symptomatology. Further analyses are needed to determine factors associated with higher use of CAM among patients with thyroid cancer and whether this use affects their cancer care and compliance with conventional medical therapy.

We note a significant proportion of respondents with thyroid cancer are not asked, nor do they tell their physicians about their CAM use. Despite the evidence that patients are using CAM modalities at a significant rate and the significant data on CAM use that are available to clinicians, there is clearly room for improvement in communication between providers and patients. Obstacles may include a lack of confidence in communicating with patients and a lack of knowledge of CAM and its effect on health care outcomes. Physicians and trainees in all health professions represent a prime target for curricula about CAM. Physicians may be aware that patients are using CAM, but many respondents reported that being “asked” meant only filling in a box on forms without the physician asking any further questions. This indicates that CAM use is not treated in the same manner as other types of medications. Movement to an electronic medical record should incorporate questions regarding CAM into the medication section, which would facilitate evaluating drug–herb interactions. Knowledge of side effects and medication interactions is limited because the data are poor. Because most CAM modalities are accessible without prescription, patients may not turn to their physician for information on CAM use, which potentially harms patient–provider communication.

Strengths of our data include the following: this is a well-designed survey by experts in the field, with an excellent item nonresponse rate and a large sample size. Responders were from a socioeconomically diverse group with a large sample size and represented the largest study group to date in a specific cancer type. The major limitation of the study is the potential for selection bias because this was a highly self-selected sample surveyed during distributed online to members of a large thyroid cancer survivors' group studied over one time period, although the link was available to anyone who logged on to the websites. We did not ask about the use of marijuana or other drugs because this has been described as reducing response rate in surveys in the past (29). A comparison to other thyroid cancer survivor groups and to patients with thyroid cancer who are not members of survivor groups is currently ongoing. We compared our data with historical published controls. In addition, data were based on self-report rather than direct observation or medical record review. The response rate, while respectable for an online survey with no reimbursement, could have been higher. What does and does not constitute a CAM therapy is also debatable. Finally, the responses generated by this survey cannot be assumed to be representative of specific medical practices, since the patients reporting did not always specify who had asked them about CAM use (i.e., whether their endocrinologist, surgeon, or primary care physician).

Conclusions

This study provides the first data regarding CAM use in patients with thyroid cancer from a nationally representative sample. These data suggest that overall use of CAM in patients with thyroid cancer is higher than the general U.S. population or other cancer survivors. The characteristics of respondents are similar to the demographics for patients with thyroid cancer in the United States; for example, ethnicity, age, sex, education, treatment status, and treatment course. We identified a substantial need for improvement in clinician and patient communication regarding CAM practices. This survey does not address whether patients are benefiting from or harmed by use of these therapies. Futures studies will analyze the open-ended textual responses to assess the specific reason for CAM use because this could be used to identify where patients with thyroid cancer turn to CAM. In addition to learning about the safety, effectiveness, and interactions of specific CAM therapies with conventional care, patients and their physicians will need to communicate more consistently about CAM use to enable documentation of patient use and potential interactions. Effective educational interventions and well-designed research plans are predicated on the collection of this kind of data.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose. No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Barnes PM. Bloom B. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;12:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM. Powell-Griner E. McFann K. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahin RL. Barnes PM. Stussman BJ. Bloom B. Costs of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and frequency of visits to CAM practitioners: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;18:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg DM. Davis RB. Ettner SL. Appel S. Wilkey S. Van Rompay M. Kessler RC. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druss BG. Rosenheck RA. Association between use of unconventional therapies and conventional medical services. JAMA. 1999;282:651–656. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberg DM. Kessler RC. Foster C. Norlock FE. Calkins DR. Delbanco TL. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fouladbakhsh JM. Stommel M. Given BA. Given CW. Predictors of use of complementary and alternative therapies among patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:1115–1122. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1115-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izzo AA. Ernst E. Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review. Drugs. 2001;61:2163–2175. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler SR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer. Med Anthropol Q. 1999;13:214–222. doi: 10.1525/maq.1999.13.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afifi FU. Wazaify M. Jabr M. Treish E. The use of herbal preparations as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a sample of patients with cancer in Jordan. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010;16:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akyuz A. Dede M. Cetinturk A. Yavan T. Yenen MC. Sarici SU. Dilek S. Self-application of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64:75–81. doi: 10.1159/000099634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Algier LA. Hanoglu Z. Ozden G. Kara F. The use of complementary and alternative (non-conventional) medicine in cancer patients in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2005;9:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin M. Glynn F. Rowley S. O'Leary G. O'Dwyer T. Timon C. Kinsella J. Complementary medicine use in patients with head and neck cancer in Ireland. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:1291–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin M. Hughes J. Timon C. Kinsella J. Quackery in head and neck cancer. Ir Med J. 2008;101:82–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashikaga T. Bosompra K. O'Brien P. Nelson L. Use of complimentary and alternative medicine by breast cancer patients: prevalence, patterns and communication with physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:542–548. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astin JA. Reilly C. Perkins C. Child WL. Breast cancer patients' perspectives on and use of complementary and alternative medicine: a study by the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006;4:157–169. doi: 10.2310/7200.2006.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balneaves LG. Truant TL. Kelly M. Verhoef MJ. Davison BJ. Bridging the gap: decision-making processes of women with breast cancer using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:973–983. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baum M. Cassileth BR. Daniel R. Ernst E. Filshie J. Nagel GA. Horneber M. Kohn M. Lejeune S. Maher J. Terje R. Smith WB. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in the management of early breast cancer: recommendations of the European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA) Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1711–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buentzel J. Muecke R. Schaefer U. Micke O. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in head and neck cancer—is it really limited [corrected] Laryngoscope. 2006;116:506–507. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000194229.72831.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canales MK. Geller BM. Surviving breast cancer: the role of complementary therapies. Fam Community Health. 2003;26:11–24. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter CL. Ganz PA. Bernstein L. Complementary and alternative therapies among very long-term breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassileth BR. Deng G. Complementary and alternative therapies for cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:80–89. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tasaki K. Maskarinec G. Shumay DM. Tatsumura Y. Kakai H. Communication between physicians and cancer patients about complementary and alternative medicine: exploring patients' perspectives. Psychooncology. 2002;11:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pon.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen MH. Eisenberg DM. Potential physician malpractice liability associated with complementary and integrative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:596–603. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-8-200204160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemper KJ. Amata-Kynvi A. Dvorkin L. Whelan JS. Woolf A. Samuels RC. Hibberd P. Herbs and other dietary supplements: healthcare professionals' knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics., National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Public-use data release. www.cdc.gove/nchs/nhis/nhis_2007_data_release.htm. [May 11;2012 ]. www.cdc.gove/nchs/nhis/nhis_2007_data_release.htm

- 28.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons Inc.; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biemer PP. Witt M. Repeated measures estimation of measurement bias for self-reported drug use with applications to the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. NIDA Res Monogr. 1997;167:439–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]