Abstract

Leptospirosis is one of the most important zoonoses. Leptospira interrogans serovar Lai is a pathogenic spirochete that is responsible for leptospirosis. Extracellular proteins play an important role in the pathogenicity of this bacterium. In this study, L. interrogans serovar Lai was grown in protein-free medium; the supernatant was collected and subsequently analyzed as the extracellular proteome. A total of 66 proteins with more than two unique peptides were detected by MS/MS, and 33 of these were predicted to be extracellular proteins by a combination of bioinformatics analyses, including Psortb, cello, SoSuiGramN and SignalP. Comparisons of the transcriptional levels of these 33 genes between in vivo and in vitro conditions revealed that 15 genes were upregulated and two genes were downregulated in vivo compared to in vitro. A BLAST search for the components of secretion system at the genomic and proteomic levels revealed the presence of the complete type I secretion system and type II secretion system in this strain. Moreover, this strain also exhibits complete Sec translocase and Tat translocase systems. The extracellular proteome analysis of L. interrogans will supplement the previously generated whole proteome data and provide more information for studying the functions of specific proteins in the infection process and for selecting candidate molecules for vaccines or diagnostic tools for leptospirosis.

Introduction

Leptospirosis is one of the most important zoonoses, and it is recognized as a re-emerging infectious disease all over the world (Faine, 1994). Leptospira interrogans is one of the most common causative agents of leptospirosis (McBride et al., 2005), and infection with L. interrogans can lead to a variety of symptoms from headache, chill, and cough, to jaundice, abdominal pain, and even death (Faine, 1994). The early clinical manifestations of leptospirosis cannot be easily distinguished from those of other diseases such as flu, dengue, and others (Xue et al., 2009). Despite advances in prevention and therapy, the molecular mechanisms of pathogenesis in leptospirosis remain poorly understood.

The genome of the pathogenic L. interrogans serovar Lai was first sequenced in 2003, and this sequence has been a useful tool for studying biology and pathogenesis of Leptospira, especially at the molecular level. Now, another six strains of Leptospira have been sequenced (Bulach et al., 2006; Nascimento et al., 2004; Picardeau et al., 2008; Zhong et al., 2011), and draft sequences for more than one hundred strains have been deposited in GenBank. These studies have greatly facilitated our knowledge of Leptospira physiology and pathology at the genomic, transcriptomic (Hesterlee, 2001), and proteomic levels (Adler et al., 2011). Extracellular proteins are important components of bacterial biology with many critical functions, such as nutrient acquisition, cell-to-cell communication, detoxification of the environment, and attacking potential competitors (Tjalsma et al., 2004). Moreover, the extracellular proteins could function as virulence factors in pathogenic bacteria (Lei et al., 2000; Tjalsma et al., 2004). Although many reports on leptospiral proteomics, from the outer membrane to the whole cell (Cao et al., 2010; Forster et al., 2010; Nally et al., 2011; Sakolvaree et al., 2007; Thongboonkerd et al., 2009; Vieira et al., 2009), have provided useful information, the precise identity and biological significance of the extracellular proteome remains largely unexplored. Moreover, the secretion apparatus used to deliver proteins to the extracellular environment by Leptospira is completely unknown. In this study, we analyzed the protein-related delivery systems based on whole-genome and whole-proteome data and further characterized the extracellular proteome in L. interrogans serovar Lai by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This study contributes to a comprehensive overview of the secretion components and provides new candidates for further analysis of leptospiral virulence and protein function.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of protein-free C-70 medium

C-70 medium was modified from PF medium as described (Bey and Johnson, 1978) with additional supplementation of growth factor of solution A (5 mL per 1 L medium). The solution A was prepared (milligrams per 1 L of distilled water) as: vitamin B12 (4.00), benzene derivatives (4.00), vitamin B5 (8.00), L-glutathione (20.0), vitamin B6 (20.0), D-biotin (40.0), vitamin B3 (40.0), bitamin B1 (400), and L-asparagine (4000).

Culture conditions

The L. interrogans serovar lai type strain 56601 was obtained from the Institute for Infectious Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China and maintained by serial passage in hamsters to preserve its virulence. Leptospira that had been passaged in vitro for fewer than three generations were cultured in liquid Ellinghausen-McCullough-Johnson-Harris (EMJH) medium at 37°C or liquid-modified protein-free C-70 medium at 28°C under aerobic conditions for 48 h to early mid-phase at a density of approximately 108/mL. The cultures were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet the cells.

The growth of Leptospira in C-70 and EMJH medium was counted with a Petroff-Hausser chamber. Briefly, Leptospira were diluted to a density of 5×107cells/ml and cultured in liquid C-70 and EMJH medium at 28°C under aerobic conditions. Leptospira were enumerated using a dark-field microscope at every 6 h. Triplicate samples were counted.

Extraction of extracellular leptospiral proteins

Leptospira isolated from hamster and passaged in liquid C-70 medium in vitro for fewer than three generations were cultured in liquid C-70 medium at 28°C under aerobic conditions for 48 h to early mid-phase at a density of approximately 108/mL. 5×1010–1011 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were collected. The supernatant was filtered by a 0.22 μm filter unit (Millipore) to remove residual cells. Extracellular proteins were prepared by concentrating the supernatant with a 5000 Da MWCO filter (Sartorius, Viviflow 50), followed by precipitation with 4 volumes of acetone at 4°C overnight. The pellet was collected after centrifugation at 23,400 g for 30 min and dissolved in ddH2O. The extracellular proteins were monitored for purity by immunoblotting using antibodies against LA_2512, which is described elsewhere (Haake and Matsunaga, 2002).

LC-MS/MS analysis

The extracellular protein sample was digested to peptides by trypsin. An Ettan™ MDLC system (GE Healthcare) was applied to desalt and separate the tryptic peptide mixtures. In this system, the samples were desalted on RPtrap columns (Zorbax 300 SB C18, Agilent Technologies) and then separated on a RP column (150 μm i.d., 100 mm length, Column Technology Inc., Fremont, CA). Mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in HPLC-grade water and mobile phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. A 20 μg sample of tryptic peptide mixture was loaded onto the columns, and separation was performed at a flow rate of 2 μL/min using a linear gradient of 4%–50% phase B for 120 min. A FinniganTM LTQTM linear ion trap MS (Thermo Electron) equipped with an electrospray interface was connected to the LC setup to detect the eluted peptides. Data-dependent MS/MS spectra were obtained simultaneously. Each scan cycle consisted of one full MS scan in profile mode, followed by five MS/MS scans in centroid mode with the following Dynamic ExclusionTM settings: repeat count 2, repeat duration 30 sec, exclusion duration 90 sec. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Data analysis

MS/MS spectra were automatically searched against the L. interrogans serovar Lai genome database (downloaded from GenBank http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) using the BioworksBrowser rev. 3.1 (Thermo Electron, San Jose, CA). Protein identification results were extracted from SEQUEST out files with BuildSummary. Only tryptic peptides were considered, and up to two missed cleavages were allowed. The mass tolerances allowed for the precursor ions and fragment ions were 2.0 Da and 0.8 Da, respectively. The protein identification criteria used were Delta CN (≥0.1) and cross-correlation scores (Xcorr, one charge ≥1.9, two charges ≥2.2, three charges ≥3.75).

In silico analysis

The results were analyzed using several bioinformatic tools. SignalP 3.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) was used for signal peptide detection. SecretomeP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP/) was used to identify non-classical secretion pathway proteins. TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM) was used for transmembrane structure detection. The SpLip program, kindly provided by D. Hakke (Research Service, Veterans Affairs, Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA), was used to detect leptospiral lipoproteins. Psortb (http://www.psort.org/psortb/index.html), cello (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/) and SoSuiGramN (http://bp.nuap.nagoya-u.ac.jp/sosui/sosuigramn/sosuigramn_submit.html) were used to predict the localization of the identified proteins.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR detection

In vitro total RNA was extracted from L. interrogans using Trizol reagent (Roche). In vivo samples were collected from hamster livers. The hamsters were inoculated with approximately 108 L Leptospira and sacrificed at 72 h. Total RNA was extracted from the liver using Trizol reagent (Roche). Contaminating DNA was eliminated with RNase-free DNaseI (Roche), and the resulting RNA was purified using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The purified RNAs were converted to cDNA using the First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas). Primers to amplify genes encoding extracellular proteins were designed with Beacon Designer software and are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Supplementary Material is available online at www.liebertpub.com/omi). The gene transcript levels were normalized to the level of L. interrogans 16S, as described previously (Matsui et al., 2012).

Results and Discussion

Extracellular proteomic analysis of L. interrogans serovar Lai

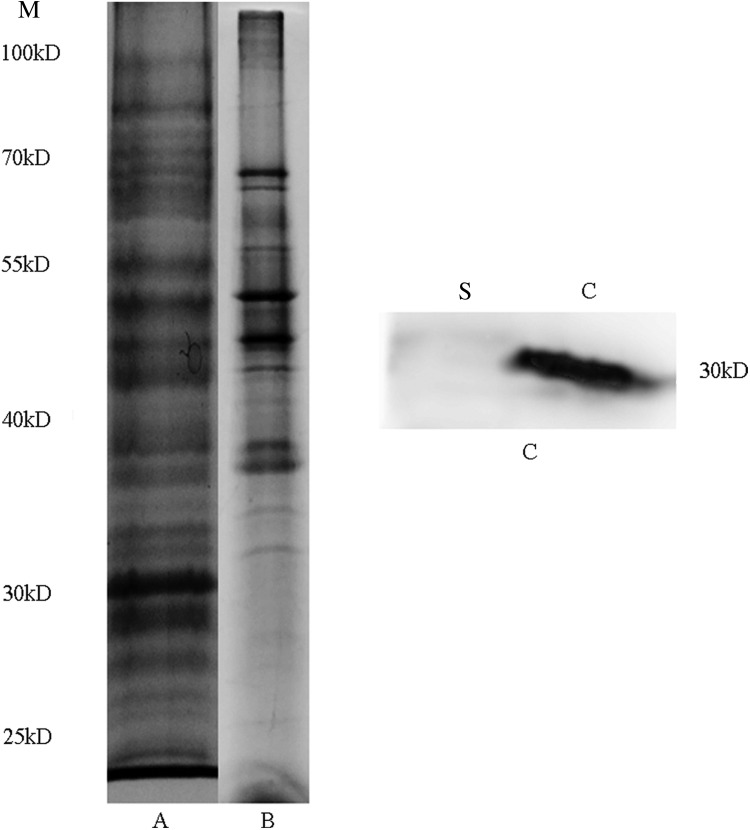

Previous proteomic studies have mostly focused on leptospiral outer membrane proteins or vesicles. EMJH and Korthof's medium are commonly used to culture Leptospira, but both contain BSA or serum. Growth in a protein-free medium is preferable to obtain the pure secretion proteome. C-70 is the modified medium to culture the Leptospira without protein component in this study. The growth of Leptospira in C-70 medium reached the stationary phage at about 60 h, which was similar to that of EMJH (Fig. 1), although a slightly lower cell yield was achieved in C-70 than in EMJH medium. For preparing the extracellular protein, Leptospira were cultured in C-70 medium to early mid-phase, and the supernatant was collected as the secretion proteome and the purity was checked with SDS-PAGE and Western Blot (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

The growth curve of L. interrogans serovar Lai cultivated in protein-free medium C-70 and EMJH. Leptospira were diluted to a density of 5×107cells/mL and grown at 28°C in medium C-70 and EMJH. Triplicate samples were counted under a dark-field microscope with a Petroff-Hausser cell counter. Differences among the three groups were nonsignificant at all time points (p>0.05).

FIG. 2.

The profile of L. interrogans lysates and extracellular proteins. (A) The lysates of L. interrogans. (B) The extracellular proteins of L. interrogans. The protein were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and stained with Coomassie blue. (C) Equal amounts of protein from whole lysates and extracellular protein of L. interrogans were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antiserum against LA_2512. Migration of protein standards is shown to the left in kilodaltons. Abbreviations: C, whole cell of L. interrogans; M, protein marker; S, supernatant of L. interrogans.

LTQ MS/MS spectra obtained from the supernatant were searched against the NCBI database of strain 56601 annotations (Download from the GenBank: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). We selected CDSs matched by at least two unique peptides, for a total of 66 detected proteins. Compared with other gram-negative bacteria, L. interrogans secretes few extracellular protein (Viratyosin et al., 2008). Its incomplete secretion core compartment and slow growth characteristics may account for the lower number of exported protein. Nine novel CDSs that were absent from our previously published whole-cell proteomics dataset (total 2158 CDSs) from sevorar Lai were identified in this study (Supplementary Table S2) (Cao et al., 2010).

Cellular localization of the identified supernatant protein based on combined bioinformatics analysis

It has been challenging to confirm the identities of extracellular proteins. At present, Psortb, Cello, and SoSuiGramN are used to predict protein localization, while SignalP, Phobius, TMHMM, and several other programs are used to predict specific protein structures. Taken together, the results of Psortb 3.0 (Yu et al., 2010), Signal P (Bendtsen et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 1997), Cello (Yu et al., 2004), secretome P (Juncker et al., 2003), lipoP (Juncker et al., 2003), SoSuiGramN (Imai et al., 2008), TMHMM and SpLip (Setubal et al., 2006), predicted 33 proteins to be exported to the extracellular space (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Extracellular Proteins Confirmed by Bioinformatic Tools

| Locus tag | Name | Gene | COG |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA_0222 | OmpA family lipoprotein | – | COG2885M |

| LA_0411 | Electron transfer flavoprotein alpha subunit | etfA | COG2025C |

| LA_0416 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_0492 | LipL36 | lipL36 | – |

| LA_0505 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_0563 | LenC | – | – |

| LA_0739 | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | rplC | COG0087J |

| LA_0862 | Thiol peroxidase | tpx | COG2077O |

| LA_1404 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_1499 | Cytoplasmic membrane protein | – | – |

| LA_1676 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | ssb | COG0629L |

| LA_1762 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_2413 | Cell wall-associated hydrolase/lipoprotein | – | COG0791M |

| LA_2637 | LipL32 | lipL32 | – |

| LA_2823 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3091 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_3240 | LipL48 | lipL48 | – |

| LA_3242 | TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor | – | COG1629P |

| LA_3276 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_3340 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3394 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3416 | 30S ribosomal protein S7 | rpsG | COG0049J |

| LA_3437 | Bifunctional translation initiation inhibitor (yjgF family)/endoribonuclease L-PSP | tdcF | COG0251J |

| LA_3442 | Peroxiredoxin | bcp | COG1225O |

| LA_3469 | Putative lipoprotein | irpA | COG3487P |

| LA_3705 | DnaK | dnaK | COG0443O |

| LA_3874 | Acid phosphatase | surE | COG0496R |

| LA_3881 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_4291 | Hypothetical lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_4292 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_4324 | LenE | – | – |

| LB_194 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LB_327 | Aconitate hydratase | acn | COG1048C |

Functional categorization of the extracellular proteome

Virulence factors

Loa22 has been confirmed as a pathogenic factor (Adler et al., 2011; Ristow et al., 2007) in L. interrogans. In our study, Loa22 was detected in the supernatant, indicating that this protein might interact with host in its extracellular form. Other potential virulence factors, such as LA_0505 and LenC, were also detected in the secretion proteome.

Host interaction proteins

One of the important roles of extracellular proteins is in host interaction during infection (Stathopoulos et al., 2000). Adhesion is one of the major processes of pathogen infection of a host. Five adhesion candidates, such as LipL32 (Hoke et al., 2008), Loa22 (Ristow et al., 2007), LenC, LenE (Stevenson et al., 2007), and LA0505 (LIC13050) (Pinne et al., 2010) were identified in our extracellular proteomics data. These proteins have all been reported as outer membrane proteins in Leptospira (Chaemchuen et al., 2011; Haake and Matsunaga, 2002; Pinne et al., 2010; Ristow et al., 2007; Stevenson et al., 2007). The detection of these proteins in the extracellular proteome further supports the hypothesis that these proteins interact directly with the host during infection.

Cellular process proteins

Three of the proteins detected in the secretion proteome have been reported to be related to Leptospira survival. The putative lactoylglutathione lyase encoded by LA_1417 (Ozyamak et al., 2010) is a component of the glutathione-dependent glyoxalase system. This system is related to bacterial survival during glycation stress. LA1953 encodes an ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2009; Marchler-Bauer and Bryant, 2004; Marchler-Bauer et al., 2011). ClpP is a potential target for modulating the presentation of protective antigens such as LLO and thereby the immune response against L. monocytogenes (Gaillot et al., 2001). It is also important for growth under stress conditions in S. typhimurium (Thomsen et al., 2002). LA_2809 encodes peroxiredoxin, which takes part in the bacterial antioxidant defense (Dubbs and Mongkolsuk, 2007; Tripathi et al., 2009). It was reported that the secreted proteins could function to help bacteria adapt to their environment (Haake and Matsunaga, 2002). These secreted cellular process-related proteins might help L. interrogans adapt to different environments.

Lipoproteins of Leptospira

Lipoproteins play important roles in the physiological and pathogenic processes in gram-negative bacteria (Kovacs-Simon et al., 2011). Lipoproteins can trigger the host inflammatory response and are important during the infection process (Schroder et al., 2008). A total of 167 lipoproteins were predicted by SpLipV1 analysis of the L. interrogans serovar Lai genome (Setubal et al., 2006). Among the exported proteins detected in our analysis, eight were lipoproteins (Supplementary Table S3). Although LipL32 is one of the most abundant outer membrane proteins in L. interrogans (Haake et al., 2000), its role in pathogenesis is still not clear. lipl32− mutant isolate showed the same virulence as the wild type, which indicates that LipL32 does not play a key role in pathogenesis (Murray et al., 2009). Expression of LipL36 is temperature dependent and is downregulated when L. interrogans is cultured at a temperature over 30°C or during the infection (Nally et al., 2001). The downregulation of LipL36 might be important for Leptospira to survive the infection process. It has been reported that LipL48 could be downregulated in response to oxygenic pressure, which might be a potential virulence factor (Xue et al., 2010). Although it is difficult to distinguish whether these three abundant proteins are contaminants or true exported proteins. The function of their extracellular forms should be studied further to determine their importance. The function of the other five lipoproteins remains unknown.

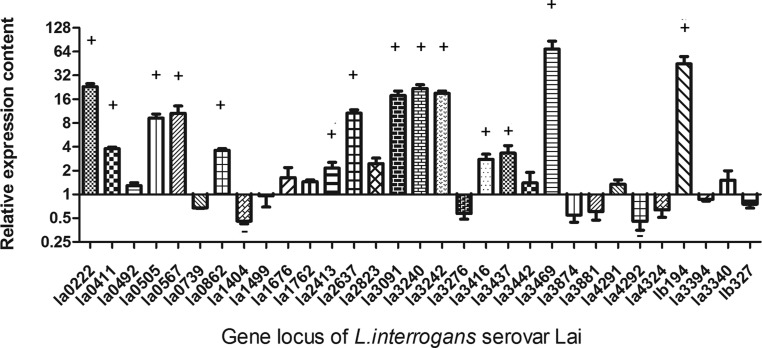

Differential transcriptional analysis of the extracellular proteins produced in vitro and in vivo

Extracellular and surface-exposed proteins are the molecules that make direct contact with host elements when the pathogens invade the host. It has thus been proposed that these extracellular proteins are the molecules that initiate many host responses (Rolando and Buchrieser, 2012; Shames and Finlay, 2012; Ustun et al., 2012). To analyze gene expression during Leptospira infection, real time PCR was used to detect the transcription levels of the 33 bioinformatically identified exported proteins (Fig. 3). The results showed that 15 of these 33 genes were upregulated, and two were downregulated in vivo. Among the 15 upregulated genes, virulence factors, including Loa22 and LipL32, were found. LA_3242 is another upregulated gene that encoded TonB-dependent receptor related to Fe2+ absorption. Since iron availability is low in the host, it presumed that upregulation of this gene might help Leptospira acquire iron and establish infection. LipL48 is one of the most abundant lipoprotein in L. interrogans. It was reported the transcriptional level of lipL48 was downregulated when Leptospira were co-cultured with phagocytes (Xue et al., 2010). However, it showed that the lipL48 was upregulated when Leptospira infected with the host. The function of LipL48 needs further study.

FIG. 3.

The transcriptional differences of L. interrogans serovar Lai extracellular proteins encoding genes between in vivo and in vitro. Hamsters inoculated with L. interrogans serovar Lai were used as in vivo models. Real-time PCR was used for comparing the transcriptional level between in vivo and in vitro. + means these genes were upregulated twice in vivo compared to in vitro. – means these genes were downregulated twice in vivo compared to in vitro.

Analysis of L. interrogans serovar Lai secretion systems

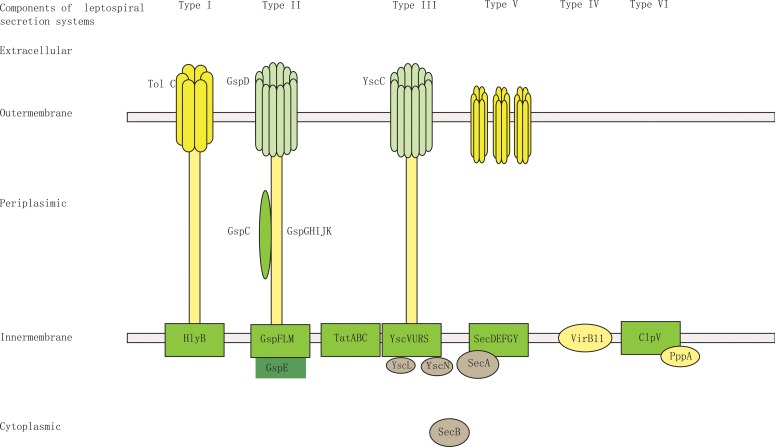

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has focused on exported proteins and export-related machinery in Leptospira. Leptospira is a gram-negative bacteria that possesses an inner membrane and outer membrane. Gram-negative bacteria have evolved different methods of protein export (Tseng et al., 2009). The genome sequence of L. interrogans serovar Lai was completed in 2003, and the corresponding 4727 protein-coding sequences (CDSs) are available in GenBank (Ren et al., 2003). It was reannotated based on whole proteomics data, reducing the number of protein-coding sequences to 3718 CDSs (Zhong et al., 2011). Of these 3718 CDSs, 2158 can be detected in the high-accuracy tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) spectra obtained by the Yin-yang multidimensional liquid chromatography (MDLC) system coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Cao et al., 2010). Based on the genomic and proteomic data available for L. interrogans (Cao et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2011), we performed an in silico analysis of the secretion machinery components of L. interrogans serovar Lai. BLASTP search for homologs of components of the secretion systems of type I, type II, type III, type IV, type V, and type VI (Cao et al., 2010; Hayes et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2003) in the NCBI database revealed presence of many secretion-related genes in the L. interrogans genome. Combined with whole cell proteomics data (Cao et al., 2010), it showed that L. interrogans possesses a relatively complete type I secretion system and type II secretion system and incomplete type III, type IV, type V, and type VI secretion systems. (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Schematic figures of the secretion systems in L. interrogans serovar Lai are shown in Figure 4. Furthermore, complete Sec translocase and Tat translocase systems were also found in its genome.

FIG. 4.

Schematic of the predicted secretion systems of L. interrogans serovar Lai. L. interrogans serovar Lai is a gram-negative bacteria that possesses an inner membrane and outer membrane. Based on the genomic and proteomic data available for L. interrogans (Cao et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2011), BLASTP was used to search for homologs of components of the secretion system of T1SS, T2SS, T3SS, T4SS, T5SS, and T6SS in the NCBI in the L. interrogans genome and further to confirm the expression of the components by whole cell proteomics data search. This figure shows the schematic of a relatively complete T1SS and T2SS and incomplete T3SS, T4SS, T5SS, and T6SS in L. interrogans serovar Lai.

Type I secretion system

TolC genes can function with several types of transporters or alone to create trans-periplasmic channels (Saier, 2006), and the relationship between TolC channels and the type I secretion system is well defined. It has been reported that the type I secretion system can export hemolysins to the extracellular environment. Although no hemolysins were detected in our extracellular proteomic assay, there are at least 11 hemolysins in the L. interrogans genome. As L. interrogans can cause pulmonary hemorrhage, which is typically caused by hemolysins during infection, it is presumed that type I secretion system is active and functions to export the hemolysins during this process.

Type II secretion system

The general secretion system is a major pathway for the translocation of unfolded proteins across the inner membrane. Among them, the type II secretion system is broadly conserved in gram-negative bacteria that secrete enzymes and toxins across the outer membrane. Proteins secreted following this pathway contain an N-signal peptide (Rahimi and Kheirabadi, 2012). The precise assembly of type II secretion system requires a set of Gsp proteins. Nine Gsp proteins (GspD, GspC, GspF, GspG, GspJ, GspK, GspL, GspM, and GspE) have been identified in the L. interrogans genome and proteome, suggesting that this strain has a relatively complete type II secretion system. Among the 66 secreted proteins identified in our studies, 14 appeared to have signal peptides (Sec-dependent pathways) (Table 2) and thus might be exported through the type II secretion system pathway.

Table 2.

Sec-Dependent Secretion Proteins

| Locus tag | Name | Gene | COG |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA_0222 | OmpA family lipoprotein | – | COG2885M |

| LA_0492 | LipL36 | lipL36 | – |

| LA_0505 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_0563 | LenC | – | – |

| LA_1404 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_2413 | Cell wall-associated hydrolase/lipoprotein | – | COG0791M |

| LA_2637 | LipL32 | lipL32 | – |

| LA_3091 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_3240 | LipL48 | lipL48 | – |

| LA_3242 | TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor | – | COG1629P |

| LA_3469 | Putative lipoprotein | irpA | COG3487P |

| LA_3881 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_4291 | Hypothetical lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_4292 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

Twin arginine translocation systems

The twin arginine translocation (Tat) system is composed of TatA, TatB, and TatC. The Tat pathway mainly exports fully folded and assembled enzyme complexes from the cytoplasm to the periplasm in bacteria, distinct from the case in general secretion systems. The target proteins exported by the Tat pathway require a specific amino-terminal signal sequence, R-R-X-F-L-K, which is cleaved after exportation. In silico analysis revealed the presence of TatA, TatB, and TatC in the L. interrogans genome and proteome.

Nonclassical secretion pathway

The Sec- and Tat-dependent pathways are referred to as the classical secretion pathways (Bendtsen et al., 2005). In addition, there is a nonclassical secretion pathway in bacteria that is independent of the Sec and Tat pathways. Secretome P is a tool that can be used to predict whether a protein is secreted by the nonclassical secretion pathway (Bendtsen et al., 2005). In our study, Secretome P analysis indicated that 18 out of the 66 secreted proteins are predicted to be exported through the nonclassical secretion pathway (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nonclassical Secretion Pathway Proteins

| Locus tag | Name | Gene | COG |

|---|---|---|---|

| LA_0411 | Electron transfer flavoprotein alpha subunit | etfA | COG2025C |

| LA_0416 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_0739 | 50S ribosomal protein L3 | rplC | COG0087J |

| LA_0862 | Thiol peroxidase | tpx | COG2077O |

| LA_1499 | Cytoplasmic membrane protein | – | – |

| LA_1676 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein | ssb | COG0629L |

| LA_1762 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_2823 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3276 | Hypothetical protein | – | – |

| LA_3340 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3394 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LA_3416 | 30S ribosomal protein S7 | rpsG | COG0049J |

| LA_3437 | Bifunctional translation initiation inhibitor (yjgF family)/endoribonuclease L-PSP | tdcF | COG0251J |

| LA_3442 | Peroxiredoxin | bcp | COG1225O |

| LA_3705 | DnaK | dnaK | COG0443O |

| LA_4324 | LenE | – | – |

| LB_194 | Putative lipoprotein | – | – |

| LB_327 | aconitate hydratase | acn | COG1048C |

Conclusion

In this study, we grew L. interrogans serovar Lai in protein-free medium to obtain its set of extracellular proteins for analysis by LC/MS. Many virulence factors were detected in the supernatant of L. interrogans serovar Lai, providing new insights into the pathogenesis of leptospirosis. Furthermore, we identified homologs of several secretion system components in L. interrogans by BLAST search of the whole genome and proteome data (Cao et al., 2010). The results revealed the presence of active secretion systems and thus protein secretion capability. Many proteins have been reported to function remotely in their extracellular forms, and this might explain why Leptospira can cause severe lung hemorrhage, despite the fact that few Leptospira are detected in the host lung. Extracellular proteins are also components of the bacterial proteome. Although there might be additional secretory protein(s) not identified by the C-70 culture medium, which may only be relevant to pathogen growth in protein-rich media or during infection of the hosts. No previous global proteomic research of Leptospira has included the extracellular proteins, and these studies therefore cannot actually represent the entire Leptospira proteome. Our study might be considered as a supplement to these other proteomics analyses, especially whole proteome studies. Furthermore, it reminded us that we should also pay attention to the function of secretory proteins that are not easily detected both in vivo and in vitro.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81101264, 81171587, 81271793, 81201334 and 81261160321).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicting financial interests.

References

- Adler B. Lo M. Seemann T. Murray GL. Pathogenesis of leptospirosis: The influence of genomics. Vet Microbiol. 2011;153:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD. Kiemer L. Fausboll A. Brunak S. Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD. Nielsen H. Von Heijne G. Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey RF. Johnson RC. Protein-free and low-protein media for the cultivation of Leptospira. Infect Immun. 1978;19:562–569. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.562-569.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulach DM. Zuerner RL. Wilson P, et al. Genome reduction in Leptospira borgpetersenii reflects limited transmission potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:14560–14565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao XJ. Dai J. Xu H, et al. High-coverage proteome analysis reveals the first insight of protein modification systems in the pathogenic spirochete Leptospira interrogans. Cell Res. 2010;20:197–210. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaemchuen S. Rungpragayphan S. Poovorawan Y. Patarakul K. Identification of candidate host proteins that interact with LipL32, the major outer membrane protein of pathogenic Leptospira, by random phage display peptide library. Vet Microbiol. 2011;153:178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbs JM. Mongkolsuk S. Peroxiredoxins in bacterial antioxidant defense. SubCell Biochem. 2007;44:143–193. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6051-9_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faine S. Leptospira and Leptospirosis. 1st. CRC Press, the Chemical Rubber Company Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Forster F. Han BG. Beck M. Visual proteomics. Methods Enzymol. 2010;483:215–243. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)83011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillot O. Bregenholt S. Jaubert F. Di Santo JP. Berche P. Stress-induced ClpP serine protease of Listeria monocytogenes is essential for induction of listeriolysin O-dependent protective immunity. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4938–4943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.8.4938-4943.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake DA. Chao G. Zuerner RL, et al. The leptospiral major outer membrane protein LipL32 is a lipoprotein expressed during mammalian infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake DA. Matsunaga J. Characterization of the leptospiral outer membrane and description of three novel leptospiral membrane proteins. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4936–4945. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4936-4945.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes CS. Aoki SK. Low DA. Bacterial contact-dependent delivery systems. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:71–90. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesterlee SE. Recognizing risks and potential promise of germline engineering. Nature. 2001;414:15. doi: 10.1038/35102259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoke DE. Egan S. Cullen PA. Adler B. LipL32 is an extracellular matrix-interacting protein of Leptospira spp. and Pseudoalteromonas tunicata. Infect Immun. 2008;76:2063–2069. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01643-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K. Asakawa N. Tsuji T, et al. SOSUI-GramN: High performance prediction for sub-cellular localization of proteins in gram-negative bacteria. Bioinformation. 2008;2:417–421. doi: 10.6026/97320630002417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juncker AS. Willenbrock H. Von Heijne G. Brunak S. Nielsen H. Krogh A. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in Gram-negative bacteria. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1652–1662. doi: 10.1110/ps.0303703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Simon A. Titball RW. Michell SL. Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect Immun. 2011;79:548–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B. Mackie S. Lukomski S. Musser JM. Identification and immunogenicity of group A Streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6807–6818. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6807-6818.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A. Anderson JB. Chitsaz F, et al. CDD: Specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D205–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A. Bryant SH. CD-Search: Protein domain annotations on the fly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W327–331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A. Lu S. Anderson JB, et al. CDD: A Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D225–229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui M. Soupe ME. Becam J. Goarant C. Differential in vivo gene expression of major Leptospira proteins in resistant or susceptible animal models. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:6372–6376. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00911-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride AJ. Athanazio DA. Reis MG. Ko AI. Leptospirosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2005;18:376–386. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000178824.05715.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GL. Srikram A. Hoke DE, et al. Major surface protein LipL32 is not required for either acute or chronic infection with Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:952–958. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01370-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nally JE. Monahan AM. Miller IS. Bonilla-Santiago R. Souda P. Whitelegge JP. Comparative proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the urine of reservoir hosts of leptospirosis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nally JE. Timoney JF. Stevenson B. Temperature-regulated protein synthesis by Leptospira interrogans. Infect Immun. 2001;69:400–404. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.400-404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento AL. Verjovski-Almeida S. Van Sluys MA, et al. Genome features of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:459–477. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H. Engelbrecht J. Brunak S. Von Heijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozyamak E. Black SS. Walker CA, et al. The critical role of S-lactoylglutathione formation during methylglyoxal detoxification in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1577–1590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07426.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picardeau M. Bulach DM. Bouchier C, et al. Genome sequence of the saprophyte Leptospira biflexa provides insights into the evolution of Leptospira and the pathogenesis of leptospirosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinne M. Choy HA. Haake DA. The OmpL37 surface-exposed protein is expressed by pathogenic Leptospira during infection and binds skin and vascular elastin. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi E. Kheirabadi EK. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in bovine, buffalo, camel, ovine, and caprine milk in Iran. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:453–456. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren SX. Fu G. Jiang XG, et al. Unique physiological and pathogenic features of Leptospira interrogans revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature. 2003;422:888–893. doi: 10.1038/nature01597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ristow P. Bourhy P. McBride FWDC, et al. The OmpA-like protein Loa22 is essential for Leptospiral virulence. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:e97. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolando M. Buchrieser C. Post-translational modifications of host proteins by Legionella pneumophila: A sophisticated survival strategy. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:369–381. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saier MH., Jr. Protein secretion and membrane insertion systems in gram-negative bacteria. J Memb Biol. 2006;214:75–90. doi: 10.1007/s00232-006-0049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakolvaree Y. Maneewatch S. Jiemsup S, et al. Proteome and immunome of pathogenic Leptospira spp. revealed by 2DE and 2DE-immunoblotting with immune serum. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2007;25:53–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder NW. Eckert J. Stubs G. Schumann RR. Immune responses induced by spirochetal outer membrane lipoproteins and glycolipids. Immunobiology. 2008;213:329–340. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setubal JC. Reis M. Matsunaga J. Haake DA. Lipoprotein computational prediction in spirochaetal genomes. Microbiology. 2006;152:113–121. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shames SR. Finlay BB. Bacterial effector interplay: A new way to view effector function. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos C. Hendrixson DR. Thanassi DG. Hultgren SJ. St Geme JW., 3rd Curtiss R., 3rd Secretion of virulence determinants by the general secretory pathway in gram-negative pathogens: An evolving story. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1061–1072. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson B. Choy HA. Pinne M, et al. Leptospira interrogans endostatin-like outer membrane proteins bind host fibronectin, laminin and regulators of complement. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen LE. Olsen JE. Foster JW. Ingmer H. ClpP is involved in the stress response and degradation of misfolded proteins in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Microbiology. 2002;148:2727–2733. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-9-2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongboonkerd V. Chiangjong W. Saetun P. Sinchaikul S. Chen ST. Kositanont U. Analysis of differential proteomes in pathogenic and non-pathogenic Leptospira: potential pathogenic and virulence factors. Proteomics. 2009;9:3522–3534. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjalsma H. Antelmann H. Jongbloed JD, et al. Proteomics of protein secretion by Bacillus subtilis: Separating the “secrets” of the secretome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:207–233. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.207-233.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi BN. Bhatt I. Dietz KJ. Peroxiredoxins: A less studied component of hydrogen peroxide detoxification in photosynthetic organisms. Protoplasma. 2009;235:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s00709-009-0032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng TT. Tyler BM. Setubal JC. Protein secretion systems in bacterial-host associations, and their description in the Gene Ontology. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun S. Muller P. Palmisano R. Hensel M. Bornke F. SseF, a type III effector protein from the mammalian pathogen Salmonella enterica, requires resistance-gene-mediated signalling to activate cell death in the model plant Nicotiana benthamiana. New Phytol. 2012;194:1046–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira ML. Pimenta DC. De Morais ZM. Vasconcellos SA. Nascimento AL. Proteome analysis of Leptospira interrogans virulent strain. Open Microbiol J. 2009;3:69–74. doi: 10.2174/1874285800903010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viratyosin W. Ingsriswang S. Pacharawongsakda E. Palittapongarnpim P. Genome-wide subcellular localization of putative outer membrane and extracellular proteins in Leptospira interrogans serovar Lai genome using bioinformatics approaches. BMC Genom. 2008;9:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F. Dong H. Wu J, et al. Transcriptional responses of Leptospira interrogans to host innate immunity: Significant changes in metabolism, oxygen tolerance, and outer membrane. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F. Yan J. Picardeau M. Evolution and pathogenesis of Leptospira spp.: Lessons learned from the genomes. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CS. Lin CJ. Hwang JK. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins for Gram-negative bacteria by support vector machines based on n-peptide compositions. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1402–1406. doi: 10.1110/ps.03479604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu NY. Wagner JR. Laird MR, et al. PSORTb 3.0: Improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y. Chang X. Cao XJ, et al. Comparative proteogenomic analysis of the Leptospira interrogans virulence-attenuated strain IPAV against the pathogenic strain 56601. Cell Res. 2011;21:1210–1229. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.